DICK OVERBOARD

14

Neighbours at Potter Heigham

A NIGHT’S SLEEP seemed to have sponged the Hullabaloos from everybody’s mind. Even Dorothea was thinking less of the dangers threatening the outlaw than of the coming voyage of the exiled Admiral home to her native Beccles. Today and tomorrow with the twins to help, and then she and Dick would have to take their places. The Teasel that morning was training ship and nothing else. Sails were set and furled three times over, just for practice. And then, hour after hour, the Teasel flew to and fro on Horsey Mere, beating, running, reaching, jibing, one thing after another, with the apprentices taking turns at tiller and mainsheet, each with a lecturing skipper.

Everything went extremely well, and when they tied up in the mouth of Meadow Dyke for their midday meal, the Admiral left Dorothea in charge of the cooking, and settled down in the cabin to write a rather boastful letter to her brother.

‘Yes,’ she wrote. ‘You may well look at the postmark. Too late to stop us. I am leaving this to be posted after we have left for the horrors of Yarmouth. So the best you can do is to wish us a good voyage. The doctor’s son is an excellent skipper, and if you could see the hard work that is being done in turning my visitors into tarry seamen, you would know you had nothing to worry about.’ Here was a picture of her brother the painter frantically tearing his hair. ‘The whole lot of them are far better sailors than you and I were when we were young.’ Here was a picture of a small girl with frilled drawers showing beneath her longish petticoats, and a small boy with a very wide-brimmed sailor hat. ‘And if you could only see the three young pirates who hover round and make themselves useful, you would know why I wish the Teasel were a little bigger. Too big for children to handle, you say? Brother Richard, I wish she were twice the size.’

‘Look here,’ said Starboard when the washing-up was over. ‘This wind is just right for getting through Meadow Dyke, and fine for the Thurne. We’ll only have to quant through Kendal Dyke. What about pushing on now, and sailing down to Thurne Mouth so as to be safe for getting home tomorrow?’

‘We ought to get home tomorrow before the A.P. comes back from Norwich,’ said Port. ‘There may be lots of things to do getting ready for next day’s race. It would be awful if we got stuck with a calm and couldn’t get back to Horning at all.’

‘And we’d better be giving the apprentices some practice in “the rule of the road”. We can do that much better in the river.’

‘Let’s just get one more bird for the list,’ said Dick.

‘No time for birds today,’ said Starboard. ‘But we’ll take one more turn across the Mere if that’ll do.’

They swept across the Mere to the far reed-beds, turned and were half-way back when, almost in a shout, Dick cried, ‘There’s our one more bird. Look! It’s a hawk. Yellow head …’

‘Marsh Harrier,’ said Tom. ‘Jolly rare.’

‘There’s another,’ said Dick. ‘Two of them.’

One bird was high above the reeds. The other, the larger one, was rising towards it. Dick tried to see them with the glasses. ‘Better without,’ he said. ‘They’re moving too quick. Not like stars. What’s that top one got in its claws?’ The two birds were flying one above another and no longer so far apart. Suddenly the first hawk dropped or threw from it the small bird it was carrying. The other turned almost on its back in the air and caught the quarry as it fell.

‘Oh, well held, sir,’ said Tom, as he would have said on seeing a good pass at a football match.

‘Why not “madam”?’ said the Admiral.

‘It ought to be “madam”,’ said Port. ‘It’s the cock bird feeding his Missis.’

‘She’s a jolly good catch,’ said Tom.

‘My goodness, Dick,’ said Starboard. ‘It’s a good thing you weren’t steering when you saw that.’

But Dick did not hear her. He was already busy with his notebook.

They sailed away now, straight through the long narrow dyke and back through Heigham Sounds. Here the wind headed them. The Sounds grew narrower and narrower. Port took the tiller from her apprentice, who was glad to give it up in this place where the Teasel had hardly left one side of the channel before she was already at the other.

‘We can’t tack through here,’ said Tom. ‘We’ll have to quant.’

‘Do let me,’ said Dick. He was still glowing from the excitement of seeing those hawks, but he had been wanting to quant ever since that day when he had seen Tom doing it while the Death and Glory was towing the Teasel into Ranworth Broad.

‘Do you think he can?’ asked Tom.

‘Current’s with us, what there is of it,’ said Starboard. ‘He’s only got to keep her moving. It’s a good chance to learn. Come on, Dick. I’ll give her a shove or two and then you be ready. Hi, you people, get the mainsheet hard in. We don’t want the boom swinging about.’

Twice Starboard, standing by the shrouds, held the long quant upright, let it slip through her hands until it found the bottom, and then leaning on it walked aft along the side deck, freed the quant from the mud with a sharp twist and jerk, and ran forward again.

‘Now then,’ she said. ‘Ready to take it?’

The quant was in Dick’s hands, and Starboard was out of the way, behind him, on the foredeck.

‘That’s right. Look out for fouling the shrouds. Let it go down.’

Funny, thought Dick. No chance of being able to lean on the end of it. The thing was nearly upright.

‘Better next time.’

‘Keep her moving,’ said Tom.

Dick galloped unsteadily forward along the narrow deck. More of a slant. That would do it. Down went the quant. There was the mud. Now push. Push. He walked aft, pushing with all his force. The next time was easier, and the next.

‘She’s moving beautifully now,’ Dorothea encouraged him, as he came aft a fourth time, leaning on the quant in the most professional manner.

The longer the push the better she moved, thought Dick. He walked to the very end of the counter and turned to hurry forward again. But what was this? The quant would not stir. He pulled. The Teasel, still moving beautifully, was leaving the quant behind. Dick hung on, pulling desperately. The counter was going away from under him.

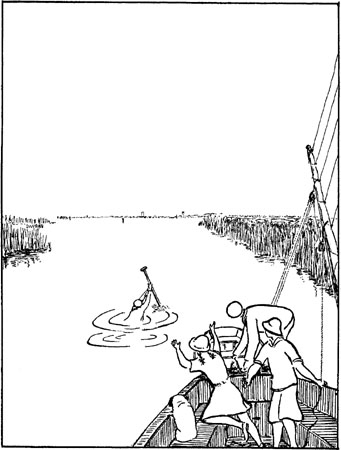

‘Grab him!’ cried Tom, but it was too late.

For one moment, Dick hung between the quant and the departing Teasel. The next he was struggling in the water.

‘Dick!’ cried Dorothea, and the Admiral, hearing the splash, came hurrying out of the cabin.

Tom was already casting off the Titmouse.

‘Don’t try to turn the Teasel,’ he shouted. ‘Not room.’

Bother those rowlocks. What a time it seemed to take to get them into their seatings. But it was only a second or two really before Tom was backing the Titmouse towards Dick who had, too late, let go of the quant, and was trying to swim and at the same time to do something with his spectacles.

‘They got off one ear,’ he spluttered. ‘Lucky I didn’t lose them. I got my cap all right. I say, I’m awfully sorry. I don’t know how it got so stuck. Pouf. Pouf.’ He spluttered out a lot of water, and grabbed hold of the Titmouse’s stern.

‘You all right?’ asked Tom.

‘Yes,’ said Dick.

‘Well, don’t waste time trying to come aboard. We’ve got to have that quant.’

The quant was loose enough now, and Tom freed it with a single tug, while Dick, blinking through his wet spectacles, trod water and held on by the transom.

‘Quant’s too long,’ said Tom. ‘We’ll have to tow it. Can you just hang on with one hand and hang on to the quant with the other, till we can let them have it again? They’ll be in a mess if we can’t let them have it quick.’

The quant was back aboard the Teasel before the apprentice who had lost it. They were very glad to have it, for already the Teasel, helpless in the narrow channel, had drifted against the reeds and was held there between wind and current. The twins, Port at the tiller, and Starboard with the quant, had her going again before Dick had scrambled in over Titmouse’s stern. A moment later he was kneeling, dripping on the Teasel’s counter. He was astonished to find that everybody was very pleased with him.

‘Well done, Dick!’ said Starboard.

‘Jolly good bit of work,’ said Port.

‘But I tumbled in,’ said Dick.

‘Everybody does that some time or other,’ said Tom, making fast the Titmouse’s painter. ‘But you’ll make a sailor all right.’

And then the Admiral, who had watched the rescue without a single word, let go Dorothea’s hand, remembered Dick’s Mother, and made him take off his wet things.

‘Well,’ she said. ‘It’s a good thing you’re not drowned, but I really don’t know how we’re going to get you dry.’

‘That’s easy,’ said Port. ‘The boatyards at Potter have got a hot room for airing mattresses and things. The people there’ll dry them for us. They’ll do it in no time.’

‘I’ve got a spare pair of bags,’ said Dick.

‘I can lend him a jersey,’ said Tom.

‘Oh,’ said Dick. … ‘How awful. I’ve got my notebook wet, the outside of it … and some of the inside, too.’

‘But you ought to be pleased,’ said Dorothea. ‘Think of explorers swimming tropical rivers. This notebook’ll be the best you’ve ever had.’

‘I bet Kendal Dyke wasn’t very tropical today,’ said Tom with a grin.

‘Do the best you can, Dick,’ said the Admiral.

Dorothea was already in the cabin, digging out a vest and drawers for him. ‘You can wear your pyjamas over the top,’ she said, ‘just till your things are dried.’

They got through the dyke, Dick himself, in flannel shorts and a pyjama jacket over a jersey much too big for him, quanting the last few yards after Starboard had shown him the twist and jerk that frees a quant from all but the most obstinate mud. Once in the river they could sail again. They swept down to Potter Heigham, lowered the mast, quanted through the bridges and tied up.

‘We’ll have to wait till those things are dry,’ said the Admiral. ‘We can’t dry them in the Teasel, and it’s no good starting on a voyage with wet clothes.’

‘We’re all right now,’ said Starboard. ‘If there’s any wind at all we can get from Potter to Wroxham tomorrow, and if there’s a calm we can take a bus. It’s not like being miles away from anywhere like we were at Horsey.’

The people at the boatyards told the Admiral it was not the first time they had had clothes to dry for a quanter who had been pulled in by his quant. They said a few hours would do the trick, and if she would wait till evening, she could have them back as dry as a bone. So, thanks to Dick, the Teasel and the Titmouse settled down to spend the night at Potter Heigham.

The Admiral painted a picture of the old bridge. The others took William for a walk, and, on their way back met a ‘Stop me and Buy one’ ice-cream boy on his tricycle. They stopped him and bought seven, of which one was wasted because it was strawberry and William decided that he did not care for any but vanilla. The Admiral wanted to take them to have a hot meal at the inn, but the twins were longing to play with the Primuses and they and Dorothea had an orgy of cooking instead … steak and kidney pies, suet and ginger puddings, green peas, and mushroom soup, all out of tins but none the worse for that, and beautifully hotted up.

But they were not allowed to forget the Hullabaloos altogether. Tom and Dorothea, as soon as they had tied up, had looked to see if George Owdon was among the idlers by the bridge. He was not, but, as time went on, they noticed that, though other people came and went, a small, tow-haired, scrubby little boy seemed unable to tear himself away.

The funny thing was that he seemed to take no interest in sailing yachts. But every time a cruiser came to the staithe the small boy left the bridge and came strolling along the bank, whistling and looking in all directions except at the cruiser, until he was near enough to be able to read her name.

‘I wonder if that’s Bill’s friend,’ said Dorothea. ‘He said he had one here, watching, and that boy was here yesterday when we went through.’

‘Soon find out,’ said Starboard. ‘Hullo, you. Looking for someone?’

‘Only for a cruiser. … Leastways not exactly. …’

‘Margoletta?’

The small boy goggled at her.

‘You lookin’ for her, too? Don’t say as I tell ye,’ he whispered.

‘That’s all right,’ said Starboard. ‘Your friend’s name is Bill.’

The small boy came a little nearer and pulled one hand from his breeches pocket. Looking about him to see that no one was watching, he opened his fingers, and showed a folded bit of grubby paper in which could be seen the shape of something flat and round.

‘Telephone money,’ he whispered darkly. ‘You got it too?’ but sauntered off without waiting for an answer. Another cruiser was coming up, and they saw that as if by accident the small boy was in the right place to meet her and ready to lend a hand with her warps. A minute or two later he was on his way back to the bridge.

‘That’s not her neither,’ he said, as he passed close by the Teasel.

‘A much better sentinel than Joe’s stomach-ache boy down at Acle,’ said the Admiral.

Not until dusk did the small boy leave his post.

‘She won’t come now,’ he said, as he passed them, pretending to look the other way, and presently disappeared behind the first of the bungalows, along the bank of the river.

‘Well,’ said the Admiral, ‘that’s all right. Nothing to worry about until tomorrow. Here’s the man with Dick’s clothes. Very nice of him to take the trouble of getting them out for us so late. And now, to bed, everybody. Poor old William’s snoring already.’

It was perhaps an hour and a half after that, or even more, when Tom, in the bottom of the Titmouse, snug in his sleeping-bag, first heard the distant throbbing of a motor boat.

It was quite dark, long after the time at which all hired cruisers are supposed to be moored for the night. For a moment, Tom thought that worry about the Margoletta had made him dream of her. But there it was, a steady, thrumming noise, and it seemed to be coming nearer. Yes. There was no doubt about it. A motor cruiser was coming up the river. Tom lay listening.

‘Tom!’

That was Dick’s voice, very low, from the other side of the centreboard case.

‘Yes.’

‘Do you hear anything?’

‘Yes.’

The noise was coming nearer and nearer.

Dick whispered, ‘Is it them?’

‘It’s the noise they make.’ Nobody could mistake that loud rhythmic thrumming.

‘No wireless this time.’

‘They oughtn’t to be moving after dark, anyway. That’s why they aren’t using it. Unless …’

‘What?’

‘Perhaps they want people to think it isn’t them.’

‘What can we do?’

‘Don’t talk.’

The noise came nearer and nearer, and suddenly lessened. An engine had been throttled down. Whatever it was, it did not want to rouse all Potter Heigham in the dark. Tom and Dick lay, silent. The awning above their heads paled for a moment as the beam of a searchlight swept across it. Tom held his breath. If they had spotted him that light would come again. It did not. Yet he could hear the cruiser close at hand. The noise of the engine changed again. Stopping. Reversing. Swinging round. Waves from the wash lifted the little Titmouse and slapped up under the counter of the Teasel. Were any of the others awake? At any moment William might start telling those people they had no right to be about. The cruiser was going ahead again. No. Again they heard her put into reverse. There was a bump against the wooden quay-heading. Someone landed heavily on the grass. Orders were being given in a low voice.

For a long time Tom and Dick listened. If it was indeed the Hullabaloos, they had tied up somewhere very near them. There was a faint murmur of talk, but not louder than might have come from any other boat. There was not a sound from the Teasel. The Admiral, the twins, Dorothea and William were all tired out and solidly asleep.

Time went on and on. The murmur ceased. There was no noise at all but the gentle tap tap of a rope against the Teasel’s mast, and the quiet lapping of the water against the quays on the other side of the river. The inn had closed long before and it had been an hour at least since the last motor car had crossed the bridge.

A breath of cold air touched Dick’s face. He woke suddenly to find that Tom was no longer lying beside him, but had got up and turned back a flap of the awning.

‘Tom.’

‘Keep quiet.’

‘What are you doing?’

‘Going to see if it’s them or not.’

Dick felt the Titmouse sway as Tom leaned out and took hold of the wooden piling along the edge of the staithe. He felt her lurch as Tom scrambled silently ashore. He fumbled for his spectacles, found them, and put them on. There wasn’t much go left in that torch of his, but it might come in useful. He wriggled himself out from under the thwart. Whatever happened he must make no noise. Ouch! That was his hand between the Titmouse and the quay. Everything was pitch black out there. He scraped a shin on the gunwale, and bumped a knee on the top of a pile, but, somehow, found himself crawling in wet grass. He waited a moment. His eyes were growing accustomed to the dark. He could see dimly the shape of the Teasel covered with her awning and not so dark as the darkness all about her. He could see the broken line made against the sky by the roofs of bungalows and boathouses. And there, just beyond the Teasel, was a huge mass, and something pale creeping towards it in the grass. Dick stood up and the next moment stumbled over a mooring rope.

There was a long silence.

Dick lay still, and so did that other creeping thing that was now close to the bows of the Teasel. In that strange moment, Dick heard the boom of a bittern far away over the marshes, but hardly noticed it. He felt his way forward, found the next mooring rope by hand instead of by tripping over it, and, at last, was close beside Tom, looking up at the dim high wall of a big cruiser’s stern.

Tom whispered, ‘I can’t read the name.’

Dick said nothing, but found Tom’s hand and pressed his torch into it.

Tom pointed the torch down towards the black water at their feet, covering the bulb with his hand so that when he switched it on, it gave out nothing but a faint red glow. He let a little more light out between his fingers. That was no good. He held the torch close against the dark stern of the cruiser and lifted it inch by inch, until it showed them the name. One half second was enough to let them know the worst—

‘MARGOLETTA’

And there was Tom, as near to the cruiser and its sleeping Hullabaloos as he had been on the evening when for the sake of No. 7 he had turned himself into a hunted creature.

There was the Margoletta within a few yards of the Teasel’s bows. Their mooring warps crossed each other. There was hardly room between them for the Margoletta’s dinghy. Aboard the Teasel, everybody was asleep. It was the same aboard the Margoletta. Even Hullabaloos must sleep sometimes, and there they slept while Tom and Dick crept home along the bank and shut themselves in once more under the Titmouse’s awning.

‘But what are you going to do?’ whispered Dick.

Tom was thinking.

‘There’s only one thing to be done,’ he said at last. ‘But we’ve got to do it without waking the others. … If William wakes he’ll wake everybody. … And it’s no good trying to do it until it’s light enough to see.’

And so, keeping awake as best they could, Tom and Dick waited for the dawn. In the end, of course, they slept, and woke in panic remembering who were their neighbours. Silently they stowed the Titmouse’s awning, unstepped her mast and made her a dinghy once more. It was already light, but everybody slept about them. The little wooden houses slept, and the boatyards, and the moored yachts, and the great threatening bulk of the Margoletta. Only the morning chorus of birds sang as if impatient to stir the sleepers.

‘They’ll go and wake William,’ whispered Dick. It was not at all the way in which he usually thought of the songs of the birds.

The worst moment was when Tom had to unlace a bit of the Teasel’s awning, so as to lift a leg of its framework and get the tiller amidships. Then, in spite of all his care, he heard someone stir in the cabin. But there was no barking.

‘Look here, Dick,’ he whispered. ‘You never have steered with a foot. But it’s quite easy. You’ve got to steer standing on the counter, so as to see over the top of the awning.’

Silently the mooring ropes were taken aboard. Silently Tom pulled the Titmouse out into the river. The tow-rope tightened. The Teasel was moving. Dick, steadying himself with a hand on the boom, steered as well as he was able.

‘ ’Sh! ’Sh!’ he whispered, as the flap of the awning was flung back, and Dorothea, like Dick, in pyjamas, looked sleepily out in time to read the dreaded name on the sleeping cruiser’s bows, as the Teasel slipped downstream, only a yard or two away.