OFF AT LAST

16

Southward Bound

TOM WOKE, REMEMBERED that the Titmouse was in the dyke at home, looked at his watch, saw that it was close on six o’clock, and, a moment later, had wriggled out of his sleeping-bag and was scrambling ashore bare-footed and in his pyjamas to have a look at the weather. The grass, wet with dew, promised well. Already there was a stirring in the leaves of the willows. Tom looked up at the gable of the house. The golden bream above the thatched roof sent him hurrying back into the Titmouse. It was heading north-west. There could not be a better wind for the voyage. North-west would be a fair wind all the way to Yarmouth, not bad for Breydon Water, and a fair wind again for most of the Waveney. With that wind, if only it held, and if they got down to Yarmouth by low water, there was no knowing how far they might not get before night. In two minutes he was dressed, stowing his dew-soaked awning, and unstepping his mast. Then he tiptoed round the house and looked up. Everybody was asleep. Goodbyes had been said the night before, but he listened almost hopefully. If our baby happened to be kicking up a row his Mother would be awake, and he could softly call her to the window. But our baby was asleep. There was not a sound except from the starlings who had, as usual, picked their way in and made a nest in the thatch. Tom poled the Titmouse quietly out of the dyke, and paddled silently upstream through the rising mist. The last of the flood tide was holding up the stream. The sooner the Teasel was off the better, to make use of the whole of the ebb. What about the others? Would young Dick have had the sense to look out at the weather and wake them up?

Presently he looked over his shoulder and saw the Teasel moored against the staithe. One look was enough. A flag was fluttering at her masthead. He had seen it taken in the night before. It was up now. One, at least, of the Teasel’s crew must be awake. And then, as he came nearer, he heard voices aboard her.

‘Well, he did say we were to get up early if the wind was north-west,’ Dorothea was saying.

‘You’d better both of you run along down the village, and you’ll find Tom’s still fast asleep.’

‘Teasel ahoy!’ said Tom softly. What a good thing it was he had happened to wake.

A flap of the awning was flung back and Dick looked out.

‘Good! Good!’ he said. ‘Here he is. Wouldn’t it have been awful if he’d come and found us still in bed?’

‘Come along, Skipper,’ said Mrs Barrable. ‘Breakfast’s ready. I don’t believe Dick’s really been to sleep at all. He was up on deck in the middle of the night.’

‘I just had one look out,’ said Dick, ‘but I didn’t go on deck till I went to put the flag up. …’

‘Hoist it,’ said Dorothea.

‘Hoist it,’ said Dick, ‘and by then the sun was up. I could see the sunshine on the tops of the trees sticking up out of the mist.’

‘He didn’t give us much chance of oversleeping,’ said Mrs Barrable. ‘So breakfast’s ready. Come along in.’

Tom climbed aboard from the Titmouse and made her painter fast to a ring-bolt on the Teasel’s counter. The Titmouse was a yacht’s dinghy once again. He looked up at the Teasel’s flag. The flagstaff was already a little askew. The morning sun was drying and slackening the halyards which had been very wet when Dick had sent the flag to the masthead. He would put that right presently. The halyards would dry a lot more yet. He took one look round, thinking already of how best to get the Teasel under way.

‘Fill his mug, Dot,’ said the Admiral. ‘Slip in here, Tom. Two eggs, Dot, and have a look at the watch when you put them in.’

Tom slipped in between table and bunk and settled down to breakfast. William, curled up on that bunk, laid his chin on Tom’s lap.

‘Look here, William,’ said the Admiral, ‘you’re my dog.’

Tom took hold of the scruff of William’s neck and gently moved it up and down, while William, his pink tongue hanging out, looked up at Tom with eyes that seemed to bulge with adoration.

‘And to think of the way he barked at you when first he met you,’ said the Admiral.

Tom laughed. Ever since that first day, he and William had had a liking for each other. But, though he rumpled William’s scruff for him, he was thinking all the time of the routine of making sail. Dick had certainly done very well in waking everybody early. Blankets had already been rolled up and stowed. Below decks nothing needed putting away except the cooking things. It was as if they had merely tied up for a meal and had rigged the awning only to keep the wind from the Primus.

‘We women’ll wash up,’ said Mrs Barrable, the moment breakfast was over. ‘And you and Dick can be getting on with things on deck.’

It was not what the Admiral called a full-dress washing up. By the time the awning was folded and doubled into a neat bundle and stowed away in the forepeak, all hands were ready for the hoisting of the sails. It seemed queer to be hoisting sail without Port and Starboard to help, but by not hurrying, and by taking a little longer about it, everything was done without mistakes.

‘Good for you, Dick,’ said Tom, when all was ready for the start. Dick had seen for himself those slackened flag halyards and was making them taut again, so that the flagstaff stuck proudly up into the sunshine, and the little flag fluttered out above the masthead.

The Admiral, in spite of herself, was looking worried. The river is so narrow up there by the staithe, and there was a hardish wind blowing. The thought of Yarmouth was in her mind, too, and in spite of her cheerful letter to Brother Richard, she could not help thinking of what he would say if anything went wrong. But Tom did seem to know exactly what he meant to do.

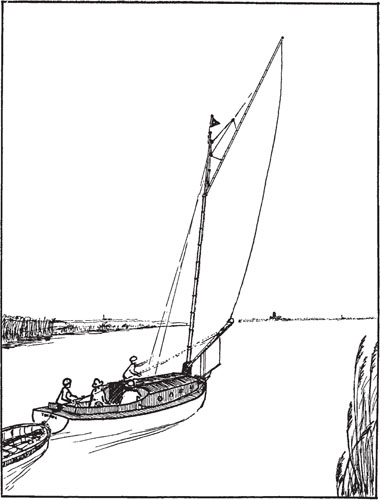

‘All ready?’ said Tom. ‘Push her head off, Dick. Come aboard.’ The Teasel was moving. Close-hauled across the river, into the wind, round again, and there she was, heading downstream. Dick was on the foredeck making a neat coil of the mooring rope. Dorothea, in the best Port and Starboard manner, was easing out the jib sheet. The staithe was left astern. They were passing the deserted boatyards. Nobody was there to see them go.

‘They folded their tents like the Arabs,’ quoted Mrs Barrable, ‘and silently stole away.’

‘But she’s making a beautiful noise,’ said Dick hurrying aft along the side deck and stepping quietly down into the well.

She certainly was. The water was creaming under her forefoot. The wind exactly suited her. Tom said nothing, but that noise was a song in his ears. If only Port and Starboard had been with them! The boatsheds were astern of them, the willow-pattern harbour, and now his own home, still asleep in the early morning sunshine. There was the entrance to his dyke, between willows and brown reeds. There, behind bushes, farther back from the river front, was the twins’ house. He looked at the windows. … No. … There was not a sign of them. Everybody was still asleep.

‘It’s an awful pity they couldn’t come,’ said Dorothea, and Tom started, at hearing his own thought spoken aloud. But it was no good thinking it. He set himself again to the business in hand. There must be no mistakes. He knew that the success of the voyage and the safety of the Teasel, and of the little Titmouse, too, towing astern, depended on him. Mrs Barrable was very good in a boat, but, talking it over among themselves, the three elder Coots had decided that the Admiral, though a good sailor, was inclined to be a little rash. And then there were the new A.B.’s. Well, they were certainly shaping like good ones. As soon as they were in a reach where there was less chance of an unexpected jibe, he would have them at the tiller, standing by, of course, in case of accident. They had managed very well with the hoisting of the sails. And there had been nothing to be ashamed of in the actual start. He wished the twins had been there to see how well their pupils had remembered what they had been taught. And now the Teasel was sweeping past the Ferry, where George Owdon had exulted too soon, and betrayed that he knew rather more than he should of the plans of the Hullabaloos. The next bit would be easy sailing.

‘Come on, Dick. Take over for a minute or two.’

Dick was ready, clutched the tiller as if he thought it might get away, watched the burgee fluttering out, and glanced astern to see how badly the Teasel’s wake betrayed the unsteadiness of his anxious steering.

‘Never mind about the wake,’ said Tom. ‘You’re doing jolly well.’

He looked into the cabin, to see what had become of the Admiral. She was sitting on her bunk with William beside her. William had decided that it was still too early for pugs to be out-of-doors. Seeing Tom, the Admiral held up some sheets of paper she had folded so that they made a little book. On the outside page she had drawn a little sailing yacht, and under that picture she had written, in very gorgeous printed letters:

‘LOG OF THE TEASEL.’

‘I forgot all about the log,’ said Tom.

‘Sailed 6.45 a.m.,’ said the Admiral. ‘Within a minute or two. Anyhow, I’ve put it down.’

‘Thank you very much,’ said Tom.

Then, leaving Dick and Dorothea alone in the well, Dick at the tiller, and Dorothea at the mainsheet, and both of them rather horrified at being left there, he went forward and stood on the foredeck, listening to the water foaming below him, and feeling somehow even more responsible than when he had the tiller in his own hands. The Admiral in the cabin noting things in the log, the two new sailors looking after the steering, and the Teasel, trembling beneath his feet with this good wind to drive her on and on towards the dangers of Yarmouth and the big rivers of the south … it was a wonderful feeling, and, anyway, it wasn’t as if he had deserted the Titmouse. There she was foaming along astern. She was coming, too, and he would be sailing her in all kinds of strange places. If only Port and Starboard could have been there to share it. Hullo, there was No. 7 that had upset all plans and made this voyage possible. How fast the Teasel was moving, although the tide, such as it was, was against her. One after another the familiar things went by. There were black sheep. Goodbye now to Horning, and the Coot Club and the Death and Glories, our baby, Father and Mother, and all those nesting birds … he would not see them again till the voyage was over and he had either made a mess of things or carried it through to success. He glanced up at the flag. They would be having the wind on the other side in the Waterworks reach, and he had better help them with the jibe. Jolly well they were doing, those two, but it was no good expecting too much of them.

The jibe, even with Tom to help, was not one that anybody aboard would have liked the twins to see. The Teasel took charge when the boom swung across, and Dick was not quick enough in meeting her with the helm. There was a wildish lurch before she settled down again, and William, who had been standing on the leeward bunk, stretching himself and yawning, was shot suddenly on the cabin floor when that bunk became the windward one. He gave a startled yelp, and came out into the well as if to warn people that things like that must not happen again.

Mrs Barrable came out, too, after marking down in the log the time at which they passed the Waterworks, but she did not seem to have noticed that fearful lurch across the river.

‘We’re getting on very well,’ she said. ‘We’ll be down at Stokesby in no time.’

‘There’s a man at Potter Heigham,’ said Tom, ‘who sailed a smaller boat than the Teasel all the way from Hickling to Yarmouth and right down to Oulton in one day with a north-west wind like this.’

They swept past the entry to the Ranworth Dyke, jibed again, more successfully, and again, not quite so well, as they turned from one reach into another in this winding bit of the river. Smoke was rising from the chimneys of Horning Hall Farm, and they saw someone moving beside the dyke.

‘What about stopping and getting milk?’ said Dorothea. ‘We used what was left of last night’s milk for breakfast, and we haven’t any now.’

‘Mustn’t waste a fair wind,’ said the Admiral, ‘must we, William?’ And William, who would have disagreed if he had understood, licked her hand most trustfully.

‘We can get milk all right at Acle,’ said Tom. ‘We’ll get it from the provision boat.’

‘Provision boat?’ said Dorothea.

‘You’ll see,’ said Tom.

At first the Teasel seemed to be the only vessel moving on the river. The few yachts and motorcruisers they passed were all moored to the banks, covered with their awnings, still asleep. But not far from Horning Hall they came round a bend in the river to find an eel-man in his shallow, tarred boat, going the rounds of his nightlines. He was a friend of Tom’s, and lifted a hand like a bit of old tree root as they swept past him, calling out their ‘Good mornings.’ Then they met a wherry quanting up with the last of the flood.

‘Hullo, young Tom,’ called the skipper of the wherry, seeing Tom at the mainsheet of the Teasel. ‘Have you seed Jim Wooddall?’

‘He’s lying above Horning,’ shouted Tom. ‘I saw old Simon on the staithe last night.’

‘Do you know everybody on the river?’ asked the Admiral.

‘I know all the wherrymen,’ said Tom. ‘You see, they all come past our house.’

Just past St Benet’s somebody in a moored yacht stuck out a tousled head from under the awning, and Dorothea wondered how the Teasel must look to him, sails set, flag flying, racing along in the sunshine while he had only just poked his nose out of a stuffy cabin. She looked at Dick, who was steering again and thinking only of his job. She looked at Mrs Barrable. How must she be feeling? ‘Day after day, week after week, the ship sailed on, and the returning exile watched till her (or his … better his) eyes grew dim for the white cliffs of home.’ But perhaps Beccles was without white cliffs. It was only too probable, and as for the returning exile, she was as usual busy with some coloured chalks, making notes for a picture. She looked more hopefully at Tom, the outlaw, flying from his home to a far country overseas. But Tom was not looking back with a tear in his eye at the country he was leaving. He seemed to be interested in nothing at all but the small bubbles or scraps of reed that were floating near the banks.

‘Tide’s turning,’ he said at last. ‘She’s done all right so far. We’ll have it with us now.’ His mind ran on, calculating. Horning to Ant’s Mouth. … Then to Thurne Mouth … then to Acle. … How long would it take to lower the mast, get through the bridge and hoist again? … Two miles to Stokesby … and then ten miles of the lower river … no trees down there, and the wind looked like holding. ‘Slacken away the jib sheet a bit more, Dot,’ he said. ‘Let’s get all the speed we can out of her.’

‘I don’t believe even the Flash goes faster than this,’ said Dorothea.

Tom knew better. A cabin yacht like the Teasel would be lucky indeed if with her small sails she could keep up with a little racer like the Flash. The thought of the Flash saddened him again by reminding him of Port and Starboard. What a pity it was that the twins were not aboard.

But there was not much time for sorrow. Already there were sails moving far away over the fields towards Potter Heigham, and they were coming to the mouth of the Thurne and the sharp turn of the Bure down towards Yarmouth, where the signpost on the bank points the way along the river roads.

Tom hauled in on the mainsheet.

‘Round with her,’ he said. ‘Steadily, right round.’

Dick pulled the tiller up. The jib flew across. There was a flap and a violent tug as the mainsail followed it. Tom paid out the sheet hand over hand. It was a beautiful jibe. The Teasel was in waters where Dick and Dorothea had never been. The outlaw, the exile and the new A.B.’s were southward bound at last.