THE WRECK WAS DRIFTING AWAY

28

Wreck and Salvage

‘TIDE’S BEGUN COMING up again,’ called Tom at last. ‘It’ll be turning in the Bure in another hour, and boats going south’ll be coming through.’

Slowly the water came licking up over the edge of the mudflats, little thin waves hurrying over the mud and going back to meet other little waves that spread wider and wider. Herons were fishing knee-deep, ready for small fish coming unsuspectingly up with the tide. With the change of the tide the fog lifted. Pale sunlight made its way through. The crew of the Teasel could see far down Breydon to the railway bridge, and up to the meeting of the rivers at the head of it. Away to the north a big black wherry sail showed above the low-lying land. The shallow creek through which the Teasel must have sailed before she stuck, filled with water. Water rose slowly round the big black posts that marked the deep-water channel. Water crept over the mud, nearer and nearer to the Titmouse. It was time to get ready. Tom’s plans were made. As soon as the Teasel floated he would tow her out into the deep water, and then they would sail back to the pilot’s moorings to wait for the morning tide.

‘Anything else to go across?’ he shouted.

‘Couldn’t you send William back by the railway before you take it down?’ suggested Dorothea.

‘Too heavy,’ said Tom. ‘He’d drag in the mud and make the Teasel as dirty as poor old Titmouse. He’s fairly clean now.’

‘You keep him,’ said the Admiral, looking up at the mention of William’s name. She was sitting on the upper edge of the sloping cabin roof, and making a sketch of Breydon at low tide, with the little Titmouse reflected in the pearly shine of the mud almost as if in water.

‘I’m going to cast off my end of the rope,’ said Tom. ‘So that I can get my mast down. Titmouse’ll be wanted as a dinghy pretty soon.’

He unfastened the rope from the halyard and dropped it on the mud. ‘Haul away!’

‘Coil it down, Twin. In with it.’

Port and Starboard, miserably thinking of tomorrow’s race, and of the A.P. without his crew, were cheered at having something to do. For a few yards they hauled in the tow-rope hand over hand, and then stopped short as they came to the part of the rope that had dragged over the mud.

‘Pretty smelly,’ said Starboard. ‘Look out. Stop pulling. We can’t stow it in the forepeak till it’s had a bit of washing.’

‘Keep it off the cabin roof,’ said Port. ‘Don’t let the mud get on the sails. Shove that jib out of the way, somebody with clean hands. Lucky we rolled it up at once.’

‘Come on, Dick,’ said Dorothea, and Dick gave up looking for the vanished spoonbills, and helped her to take the jib, rolled up round its short boom, and stow it in the cabin out of danger.

‘Hi,’ called Tom. ‘Don’t try to stow that rope in the forepeak. I’ll be using it to tow Teasel out into the channel, and that’ll wash the mud off it.’

The rope was coiled down on the foredeck, just as it was, grey with mud, and green with scraps of twisted weed, while Dick was busy winding up the string that had been used for hauling the shackle to and fro.

‘The water’s right up to me,’ called Tom. ‘I’ll be afloat in another ten minutes.’

‘It’s all round us already,’ Dorothea shouted back.

The water spread slowly over the mud between the Titmouse and the Teasel. Anyone who did not know that it was mostly only an inch deep might have thought they were afloat, except that the Teasel was leaning over on one side.

‘There’s the first boat through,’ called Dorothea.

Everybody looked down Breydon water and those two long lines of beacon posts stretching away to Yarmouth. Down there, far away, a small black spot was moving in the channel. If they had not been so busy, they would have noticed it before.

‘Only a rowing boat,’ said Starboard. ‘Probably a fisherman coming home with the tide. The water’s really coming up now. Let’s try to get afloat before he gets here.’

‘Anyway that one’s not a rowing boat,’ said Dorothea a few minutes later.

‘Motor cruiser,’ said Port, glancing over her shoulder.

‘It’s a jolly big one,’ said Starboard.

All work stopped aboard the Teasel. There was something in Starboard’s voice that held even the Admiral’s chalk in mid-air, and stopped Dick in winding the string into a ball, though he had just found the scientific way of winding it so that the turns did not slip off. Tom heard nothing. He was busy tugging at his mast, which was always rather hard to work out of its hole in the bow thwart.

‘But it can’t be,’ said Starboard. ‘Bill said yesterday they wouldn’t be able to leave Wroxham for another two days.’

‘He must have got it a day wrong,’ said Port. ‘I’m sure it’s them. Tom! Tom! Hullabaloos!’

‘Oh, hide! hide!’ cried Dorothea.

Tom turned round and stopped wrestling with the Titmouse’s mast. There could be no doubt about it. The cruiser had passed the rowing boat now, and came racing up Breydon, foam flying from her bows, a V of wash spreading astern of her across the channel and sending long bustling waves chasing one another over the mudflats. Even in the dark Tom had known the noise of the Margoletta’s engine. He knew it now, and the tremendous volume of sound sent out by her loudspeaker.

He looked this way and that. If those people had glasses or a telescope they might have seen him already. Anyhow, there could be no getting away. He felt like a fly caught in a spider’s web, seeing the spider hurrying towards it. There they were, Teasel and Titmouse, stuck on the mud in shallow water, plain for anyone to see. If only the water had risen another few inches and set them afloat. But even if it had, where could they have gone? There was only one thing to be done. It was a poor chance, but the only one. Tom made one desperate signal to the others to disappear, and, himself, slipped down out of sight on the muddy bottom boards of the Titmouse, and, holding William firmly in his arms, told him what a good dog he was and begged him to keep still.

Aboard the Teasel no one saw that signal. Their eyes were all on the Margoletta. It was not till several minutes later that Dorothea whispered, ‘Tom’s gone, anyway.’

The little Titmouse, now that the water had spread all round her over the mud, looked like a deserted boat, afloat and anchored.

On came the Margoletta, sweeping up with the tide, and filling the quiet evening with a loud treacly voice:

‘I want to be a darling, a doodle-um, a duckle-um,

I want to be a ducky, doodle darling, yes, I do.’

‘Indeed,’ muttered Port, with a good deal of bitterness.

‘Try next door,’ said Starboard.

They spoke almost in whispers, as the big motor cruiser came nearer and nearer, though no one aboard it could possibly have heard them.

‘We ought to have done like Tom and hidden,’ said Dorothea. ‘Let’s.’

‘Keep still,’ said the Admiral. ‘It’s too late now. They’re bound to notice if we start disappearing all of a sudden.’

‘Good,’ whispered Starboard. ‘They’re going right past.’

And then the worst happened.

William, still slippery with mud in spite of Tom’s pocket handkerchief, indignant at being held a prisoner while this great noise came nearer and nearer, gave a sturdy wriggle, escaped from Tom’s arms, bounded up on a thwart and barked at the top of his voice.

‘Oh! William! Traitor! Traitor!’ almost sobbed Dorothea.

‘They’ve seen!’ said Port.

The man at the wheel of the cruiser was looking straight at the Titmouse and at the Teasel beyond her.

‘Here they are,’ he suddenly shouted, to be heard even above the loudspeaker and the engine. He spun his wheel, swung the Margoletta round so sharply that she nearly capsized, and headed directly for the Titmouse. …

‘Ow! Look out!’ cried Starboard, almost as if she were aboard the cruiser and saw the danger ahead.

‘They’ve forgotten the tide,’ said Port.

The next moment the crash came. Just as the rest of the Hullabaloos poured out of the cabins, startled by the sudden way in which the steersman had swung her round, the Margoletta, moving at full speed towards the Titmouse, and swept up sideways by the tide, hit the big beacon post with her port bow. There was the cracking of timbers and the rending of wood as the planking was crushed in. Then the tide swung her stern round and she drifted on.

The noise became deafening. The loudspeaker went on pouring out its horrible song. All the people aboard the Margoletta were either shouting or shrieking and something extraordinary had happened to the engine which, after stopping dead, was racing like the engine of an aeroplane. Nobody knew till afterwards that the steersman had switched straight from ‘full ahead’ to ‘full astern’, had wrenched the propeller right off its shaft, stalled his engine, started it again and was letting it rip at full throttle, pushing his lever to and fro trying to make his engine turn a propeller that was no longer there.

Everything had changed in a moment. That crash of the Margoletta against the huge old post on which Tom had been watching the falling and the rising of the tide brought him up from the bottom boards of the Titmouse in time to see the wreck go drifting up the channel with a gaping wound in her bows and the water lapping in. No longer was he hiding from the Hullabaloos. They were shouting at him to come and save them, shouting at Tom, whom only a few moments before they had thought was a prisoner almost in their hands. And Tom was desperately rocking the Titmouse in an inch or two of water, trying to get her afloat so that he could dash to their rescue.

The three Coots, Tom, Port and Starboard, knew at once how serious was the danger of the Hullabaloos. Just for a moment or two the others were ready to rejoice that Tom had escaped them. But soon they, too, saw how badly damaged the Margoletta was. They saw, too, that the Hullabaloos, instead of doing the best that could be done for themselves, were making things far worse. The Margoletta had been towing a dinghy. Two of the men rushed aft and tried to loose the painter and bring the dinghy alongside. They hampered each other. One pulled out a knife and cut the rope, thinking the other had hold of it. The rope dropped. They grabbed at it and missed. The dinghy drifted with every moment farther out of reach. They seized a boathook, tried to catch the dinghy and lost the boathook at the first attempt.

‘She’s down by the head already,’ said Starboard. ‘Oh can’t they stop that awful song?’

The crew of the Teasel watched what was happening, hardly able to breathe. There was the cruiser drifting away with the tide up the deep channel. With every moment it was clearer that she had not long to float. Were the whole lot of the Hullabaloos to be drowned before their eyes? Would no one come to the rescue?

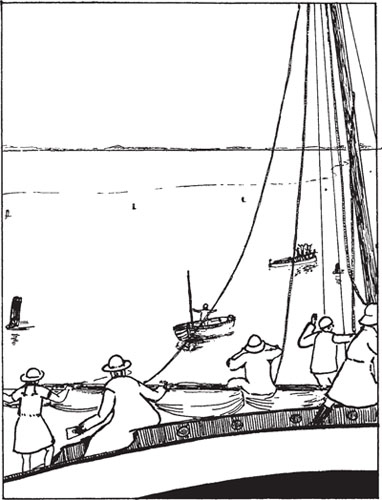

They looked despairingly towards Yarmouth. That rowing boat was coming along. But so slowly, and so far away. Too late. They would be bound to be too late, with nothing but oars to help them. But something was happening in that boat. They could see the flash of oars, but surely that was a mast tottering up and into place in the bows. And then, in short jerks, a grey, ragged, patched old lugsail, far too small for the boat, rose cockeye to the masthead. The sail filled, and the oars stopped for a moment while the sheet was taken aft.

‘Hurrah!’ shouted Port as loud as she could shout. ‘Hurrah! It’s the Death and Glories!’

Nobody else in all Norfolk had a ragged sail of quite that shape and colour. How they had got down to Breydon nobody asked at that moment. It was enough that they were there, while the Teasel and the Titmouse, still fast aground, could do nothing but watch that race between life and death. The wind was still blowing from the east, and the old Death and Glory, her oars still flashing although she was under sail, was coming along as fast as ever in her life. She might do it yet. And then the watchers turned the other way to see the drifting cruiser, her bows much lower in the water, the Hullabaloos crowded together on the roof of her after-cabin.

‘She’ll go all of a rush when she does go,’ said Starboard under her breath.

‘Deep water, too,’ said Port.

Minute after minute went by, and then the Death and Glory swept past them up the channel, her tattered and patched old sail swelling in the wind, Bill and Pete, each with two hands to an oar, taking stroke after stroke as fast as they could to help her along, while Joe stood in the stern, hand on tiller, eyes fixed on the enemy ahead who had suddenly become a wreck to be salved.

‘Go it, the Death and Glories!’ shouted Starboard.

‘Stick to it!’ ‘You’ll do it!’ ‘Hurrah!’ ‘Keep it up!’ shouted the others. And William, not in the least knowing what it was all about, jumped up first on one thwart of the Titmouse and then on another and nearly burst his throat with barking.

The noise of the engine had stopped. The shouting of the Hullabaloos was growing fainter as the Margoletta drifted up the channel with the tide.

‘It’s going to be a jolly near thing,’ said Starboard, who was looking through the glasses at the sinking cruiser already far away.

Far away up the channel the Death and Glory had drawn level with the Margoletta. Her ragged old sail was coming down. From the Teasel nothing could be heard of what was being said, but it was clear that some sort of argument was going on. They could see Joe pointing at the Margoletta’s bows. They could see the five Hullabaloos, crowded together on the roof of the Margoletta’s after-cabin, waving their arms, and, so Starboard said, shaking their fists. The two boats were close together, drew apart and closed again. A rope was thrown and missed and coiled and thrown once more.

‘But why don’t they take those poor wretches off?’ said Mrs Barrable.

Starboard laughed.

‘Boatbuilders’ children,’ she said. ‘They won’t be thinking about people when there’s a boat in danger. All they’re worrying about is not letting the Margoletta go down in the fairway. You’ll see. They’ll tow her out of the channel before they do anything else.’

She was right. The Death and Glory moved towards one of the red beacon posts on the south side of the channel, towards which the cruiser had drifted. The cruiser, at the end of the tow-rope, was following her, stern first, her bows nearly underwater. The Death and Glory left the channel, passing between one red post and the next. The Margoletta followed her. She stopped.

‘Aground,’ said Port.

‘Safe enough now,’ said Starboard. ‘Well done, Joe.’

They saw Joe jump aboard the wreck, moving on the foredeck almost as if he were walking in the water. They saw him lower the Margoletta’s mudweight into the Death and Glory. They saw the Death and Glory pulling off again, to drop the weight into the mud at the full length of its rope. Then, and then only, when the Margoletta was aground on the mud in shallow water and safe from further damage, were Joe and his fellow salvage men ready to clutter up their ship with passengers. ‘Idiots!’ said Starboard, watching through the glasses. ‘All trying to jump at once.’

‘Well,’ said Mrs Barrable, as the distance widened between the salvage vessel and the wreck, and she saw that all the Hullabaloos were aboard the Death and Glory, ‘I’m very glad that’s over.’

‘Of course,’ said Dorothea, ‘in a story one or two of them ought to have been drowned. In a story you can’t have everybody being a survivor.’

‘If it hadn’t been for the Death and Glories,’ said Port, ‘there wouldn’t have been any survivors at all. The Margoletta would have gone down in the deep water and the whole lot of them would have been drowned. What’s Joe going to do with them now? It looks as if he’s putting up his sail.’

‘He can’t do anything against the wind,’ said Starboard. ‘The Death and Glory never could. And with the tide pouring up. … Hullo! Tom’s afloat!’

‘Get the tow-rope ready on the counter,’ shouted Tom.

All this time the water had been rising. Just as the last of the Hullabaloos had left the wreck of the Margoletta Tom had felt the Titmouse stir beneath his feet. He had her mast down in a moment. Her sail had been stowed long ago. Tom got out his oars and paddled her round to the stern of the Teasel. William, welcome in spite of his muddiness, scrambled back aboard his ship. Tom made the tow-rope fast.

‘Try shifting from one side to the other,’ he said.

The Teasel’s keel stirred in the mud. The creek by which she had left the channel in the fog had filled, and Tom with short sharp tugs at his oars made the tow-rope leap, dripping, from the water.

‘She’s moving,’ said Dick.

‘She will be,’ said Starboard, pushing on the quant, while Port hung herself out as far as she could, holding the shrouds, first on one side of the ship and then on the other, and Mrs Barrable, Dick and Dorothea shifted first to one side and then to the other of the well.

‘She’s off.’

The Teasel slid into the creek. A moment later the tow-rope had been shifted to her bows and Tom was towing her back towards the channel. In a few minutes she was once more on the right side of the black beacons, drifting up with the tide, while Port and Starboard were hoisting her mainsail. The tow-rope, now more or less clean, was hauled in, hand over hand. Tom came aboard, and the little Titmouse became once more a dinghy towing astern.

‘Let’s just see if she’ll do it,’ said Starboard, looking away down Breydon to the long, railway bridge. If only they could get through that bridge they might, after all, be home in time for tomorrow’s race.

Port was busy with a mop. ‘Foredeck’s clear of mud,’ she said. ‘What about that jib?’

Dick and Dorothea were already bringing it carefully from the cabin, while the Admiral was keeping a firm hold of the muddy William, for fear he might print a paw upon it.

Up went the jib, and the Teasel went a good deal faster through the water, away across the channel to a red post on the further side. Round she came and back again. She had not gained an inch. Once more Tom took her across the channel. Once more he brought her back. No there was no doubt about it. This time she had lost ground. The wind was dropping, and the tide pouring up was sweeping her further and further from Breydon Bridge.

‘It’s no good,’ said Tom. ‘We’ll just have to go back to the pilot’s and have another shot at getting through Yarmouth tomorrow.’

‘We’re done,’ said Port. ‘It’s too late now. We’ll never get home by land tonight.’

‘And the A.P.’ll have no crew,’ said Starboard.

The Teasel, a melancholy ship, swung round and drove up with the tide to meet the Death and Glory.

The Death and Glory was desperately tacking to and fro across the channel, losing ground with every tack, even though Bill and Pete were rowing to help her sail. On the southern side of the channel, beyond the red posts, the tide was rising round the after-cabin of the Margoletta. A black speck in the distance, the Margoletta’s dinghy was drifting towards the Reedham marshes.

‘Joe,’ shouted Tom, when within hailing distance of the Death and Glory, ‘you can’t get down to Yarmouth against this tide. We can’t, either. Going back to the pilot’s?’

And at that moment Dorothea looking sadly back towards Yarmouth saw something moving on the water far away.

‘There’s another motor boat,’ she said.

‘Hullo,’ said Starboard, ‘I do believe it’s the Come Along. Where are those glasses?’

Well above Breydon railway bridge a yacht was hoisting the peak of her mainsail. The Come Along must have brought her through from the Bure, for there, already more than half-way between that yacht and the Teasel, was the little tow-boat, with the red and white flag, coming up Breydon at a tremendous pace. Old Bob had seen that something was amiss.

Joe saw the motor boat, too, and was afraid his salvage job would be snatched from him when all the work was done.

‘Them Yarmouth sharks,’ he said, and looked at the wreck. But the tide had carried him too far away already. Even with the help of those stout engines, Bill and Pete, he could not get back to stand by the wreck before this boat from Yarmouth reached it.

The Come Along seemed to be close to them almost as soon as they had sighted her. She circled once round the wreck, and then made for the Death and Glory, probably because Old Bob saw that the old black boat was carrying the shipwrecked crew.

‘You leave her alone,’ Joe was shouting at the top of his voice. ‘She ain’t derelict. Don’t you touch her. You leave her alone!’

‘Take us into Yarmouth,’ yelled the Hullabaloos.

‘She ain’t derelict,’ shouted Joe. ‘She’s out o’ the fairway. We’ve put her in shallow water, an’ laid her anchor out. She belongs to Rodley’s o’ Wroxham, an’ you leave her alone.’

Old Bob shut down his engine to listen. He laughed. ‘All right, Bor,’ he called. ‘She’ll take no harm there. I’m not robbing you. Good bit o’ salvage work you done. And where’re ye bound for now?’

‘Down to Yarmouth,’ shouted the man who had been at the wheel of the Margoletta. ‘We want to get ashore.’

The Come Along swung alongside the Teasel.

‘Good day to you, ma’am,’ said Old Bob to the Admiral. ‘Was you going down to Yarmouth, too? And so you found your ship all right?’ he added, seeing Port and Starboard smiling down at him.

‘I suppose there’s no chance now of getting through Yarmouth until tomorrow morning,’ said the Admiral. ‘The tide seems to be running very hard.’

Old Bob laughed again. ‘Take ye through now,’ he said. ‘Tide or no tide. When the Come Along say “Come along,” they got to come along. I’ll be taking this party down to Yarmouth and I’ll be taking you at the same time. If you’ll be ready to have your mast down for the bridges. You’ll have the tide with you up the North River.’

‘They’ll be in time,’ cried Dorothea.

‘We’ll do it yet,’ said Starboard.

‘Never say dee till ye’re deid,’ said Port.

‘Perhaps we ought to pick up that dinghy for them,’ said Tom, pointing it out in the distance.

‘You be getting ready,’ said Old Bob. He was off again, chug, chug, chug, chug, to catch the Margoletta’s dinghy before it had drifted ashore.

‘Oh, can’t you let the blasted dinghy go?’ shouted one of the Hullabaloos. But Old Bob did not hear him.

All was bustle aboard the Teasel. Tom sailed her to and fro close-hauled, waiting for Old Bob to come back. Port and Starboard were ready on the foredeck to lower the mainsail. Dick and Dorothea were stowing the jib once more in the cabin. Presently the Come Along came chugging back, bringing the Margoletta’s dinghy. Old Bob brought the Death and Glory’s long tow-rope and threw it to Tom aboard the Teasel. Then he threw the end of Come Along’s tow-rope across the Teasel’s foredeck. Starboard caught it and made it fast.

‘All ready?’ shouted Old Bob. ‘Mind your steering.’

Slowly he went ahead. First the Teasel and the Titmouse felt the pull of the little tug. Then the Death and Glory swung into line astern of them. They were off.

Down came the Teasel’s mainsail.

‘Come on, Tom,’ said Starboard. ‘What about getting the mast down? You’ll want to take the heel-rope, won’t you? Port’ll take the tiller.’

Tom went forward. And then, for a moment, he forgot that he had a mast to lower. He was looking at the after-cabin of the Margoletta, a melancholy island in the water. For some minutes they had heard nothing of the loudspeaker. Now, suddenly, they heard it again.

‘We now switch over. … The Hoodlum Band. … Relayed from …’ There was a pause, and then a sudden torrent of noise that broke off short almost as soon as it had begun. ‘Blaaar. Taratartara … Tara. Tara … Blaaaaaar!’ And then silence, except for the loud chugging of the Come Along.

‘Who’s turned it off at last?’ said the Admiral.

‘I expect it’s the water,’ said Dick. ‘It must have come as high as the batteries and made a short circuit. …’

‘Thank goodness it has,’ said Starboard on the foredeck close beside Tom. They settled down to the business of lowering the Teasel’s mast, while Breydon Bridge, once so impossibly out of reach, came nearer and nearer.