Mystics can be very confusing when it comes to language: they can write copiously and impressively on the subject of what they have experienced and then immediately turn around and claim that nothing can be said on that topic. How can the Daoist Laozi say “those who know do not speak, and those who speak do not know” while introducing the Daodejing, a book on the Way? To Plotinus, nothing can characterize the One, including calling it “one” (Enneads 5.3.13–14, 6.9.5). To Meister Eckhart, God is nameless, and to give him a name (as he appears to have just done) would make God part of thought and thus be an “image” (2009: 139). How can he say “God is above all names” (ibid.: 139, 153) when he identified the reality by name? Some reality is dubbed “God.” Shankara can claim that Brahman is unspeakable (avachya) and inexpressible (anirukta) while creating a metaphysical system about Brahman (Taittiriya-upanishad-bhashya 2.7.1). For him, even the words “atman” and “Brahman” are only superimpositions on what is real (Brihadaranyaka-upanishad-bhashya 2.3.6). Even “Brahman without attributes” (nirguna-brahman) is a concept devised in contrast with “Brahman with attributes” (saguna-brahman), and so even that concept must be denied as inapplicable to what is real—what is real is beyond both of these concepts, as are Advaita’s standard characterizations of Brahman as reality (sat), an inactive consciousness (chitta), and bliss (ananda) (Brahma-sutra-bhashya 3.2.22; Brihadaranyaka-upanishad-bhashya 2.3.1). For Shankara, the whole phenomenal realm of the root-ignorance (avidya) arises entirely from speech (Brahma-sutra-bhasya 2.1.27).

Why do mystics have trouble here that most people do not when they experience something phenomenal? Why is what is experienced considered inexpressible and even unnameable? It will be argued here that the tension arises for two basic reasons. First, conceptualizations must be advanced for even mystics themselves to understand what is experienced, but all conceptualizations are inherently dualistic (since they distinguish one thing from others), and so they all must also be jettisoned from the mind for a mystical experience to occur. In short, all conceptions must be both advanced and abandoned. Second, both the experiences themselves and what is experienced in these experiences seem “wholly other” than any worldly phenomena, and so any language applicable to worldly phenomena is deemed inapplicable to what is experienced. The states of consciousness in which the experiences occur are different from the mindful and ordinary states of consciousness in which mystics can depict what is experienced.

Mystical literature is quite varied (see Keller 1978), and not all mystical uses of language are declarative—prayers, parables, poetry, instructions, and other aids for transforming others or evoking experiences fall into other categories. But what is of interest here are the mystics’ cognitive claims, i.e., the assertions about the nature of the experiences and of what is experienced.1 But the “wholly other” nature of both mystical states of consciousness and what is experienced there leads mystics to believe language cannot apply. Mystics are caught in the dilemma of needing conceptualizations but realizing that any conceptualizations introduce a foreign state of consciousness. There are two problems. First, using language requires a dualistic state of mind, and thus introducing language drops mystics out of introvertive states of consciousness. This does not occur with ordinary utterances, since experiences of objects and declarative utterances about them both occur in the same state of consciousness. Even mindful states involve awareness of distinctions and thus permit the use of language. But any image of a transcendent reality is foreign to the reality itself in a way that images of phenomenal objects in the natural universe are not—transcendent realities are simply beyond our dualistic mind, and any attempt to conceptualize them introduces mental objects. Second, any concepts or statements about something transcendent will be misinterpreted by the unenlightened as referring to an object among objects in the phenomenal universe—an unusual object, granted, but simply like something in an unchartered part of the phenomenal realm. All that the unenlightened have are the mental objects produced by the analytical mind. Thus, in an important sense the unenlightened do not know what they are talking about when they use mystical concepts. The problem is not with one particular language, but with any language: no language can be devised that circumvents the problem, since all languages must have terms that make distinctions, and any terms make what is experienced into an object of consciousness, while what is experienced is free of distinctions and is not an object of consciousness.2

This causes mystics across the world to claim ineffability, i.e., what is experienced is inexpressible in any words.3 In the words of Taittiriya Upanishad 2.4: “Words and the mind turn back without reaching it.” In many everyday contexts we often find that language is inadequate. The strong emotions one feels cannot be adequately stated. Indeed, all experiences are ineffable in one sense: we cannot adequately communicate the subjective feel of any experience even if we know the appropriate labels of our culture. Describing the taste of a banana to someone who has never tasted one is impossible: we know the taste through experience, but how do we describe it? Only once one has had the experience will any description be understood. Similarly, stopping and trying to communicate what is happening at the moment often drops us out of even ordinary experiences. So too, any object of experience is ineffable in one way: any attempt to describe what is utterly unique about anything—what differentiates it from everything else—will necessarily fail, since descriptive terms all involve perceived commonalities and general categories. Using any terms to describe it will automatically group it with other things. Nominalists in the West and Buddhist logicians in India were aware of this problem—to them, “universals” are only a product of language and not components of reality. But any object is also not ineffable: it is accurate to call a pen “a pen,” even if it is only crudely “captured” by language. Thus, we do not consider phenomenal objects to be “utterly beyond words.”

Mystical experiences of course share these problems. So what is unique to mystics’ claims of ineffability? Mystics allegedly directly know a reality through their mystical experiences—so why can they not say something about it? Why do they deny “the One” or “Brahman” works for transcendent realities the way “a pen” accurately communicates for phenomenal objects? It is not that mystics sense a vague, amorphous “presence,” or have only a nebulous insight that is hard to put into words or an inarticulatable sense of knowing something—the experience is a “dazzling ray of light.” Again, the problem begins with the fact that by speaking or even thinking, mystics must switch from a mystical awareness to a dualistic state of consciousness: the mere use of language introduces a mode of awareness foreign to experiencing the reality mystically. When we speak of phenomenal objects, we merely rearrange the content of our ordinary awareness—the state of awareness remains the same. The abolition of the duality set up between subject and object causes the problem in mysticism with language. Maitri Upanishad 6.7 sums it up: “Where knowledge is of a dual nature (a knowing subject and a known object), there indeed one hears, sees, smells, tastes, and also touches. The self knows everything. But where knowledge is not of a dual nature—being without action, cause, or effect—it is without speech, incomparable, and indescribable. What is that? It is impossible to say.” Only by removing the dualities by which both language and thought operate can we realize a transcendent reality or experience beingness in an extrovertive mystical experience. Thus, mystical experiences and what is experienced both transcend language and thought.

However, mystics do make knowledge-claims. If transcendent realities exist, much about them may in fact not be relatable or comprehensible to the analytical mind, but the works of mystics suggest that they think something is. If what was experienced were truly ineffable, there would be no basis for mystics to make any knowledge-claims or value-claims about it or to deny other such claims. Ineffability cannot be the basis for any insights—something vague might be retained from the experience, but there would be no statable claims for mystics to make. What knowledge other than that something real exists and is profound could there then possibly be? What would be the insight into the nature of that reality that is given? An “ineffable insight” is not possible. However, the insight occurs in dualistic awareness when enlightened mystics see the significance of what they experienced. There they can use language to state the alleged insight.4 Even if language cannot “capture” the ever-active flow of reality, enlightened extrovertive mystics still use language, as their writings on how language fails show. Introvertive mystics also speak of the nature of what is experienced, even if the concepts used are of an abstract nature (e.g., oneness) or are terms from their religious tradition.

Theistic mystics believe they have experienced a reality that is personal in nature, and so they claim some definite things about God. God is indescribable only in that he is so much greater than they can say, not because they know nothing of him. That is, human formulations are not wrong but hopelessly inadequate (Johnston 1978: 81). But theistic mystics know that his mode of existence is utterly different than that of creatures, and so they believe that all terms mislead: we make God into a being comparable in some way to worldly beings, which he is not; hence, the concept “a being” does not apply. Even just denoting a transcendent reality as “transcendent” or “real” makes it an object, which it is not. Thus, mystics deny the adequacy of all terms. Meister Eckhart said that we cannot say anything true of God because God has no cause, no equal, and nothing from creatures is comparable to God (2009: 197–98). Indeed, he said that God is so much greater than anything that can be said that everything said about him is more like lying than speaking the truth. For example, he can say that God alone is good (2009: 300), but: “When I call God ‘good,’ I speak as falsely as if I were to call white black” (see 1981: 80). God, the creator of being, is so far above being in nonbeing (unwesen) that “I would be speaking as falsely in calling God ‘a being’ as I would if I called the sun pale or black” (2009: 342, 343).

Thus, if mystical experiences were truly ineffable, a transcendent reality may still be experienced and have a nature and we could still label it “Brahman” or “God” or whatever, but it cannot be said to be known in any other sense. There could be no insights to state and nothing to believe. No mystical statement could be true or even meaningful. Mystics could not answer David Hume’s question “How do you mystics, who maintain the absolute incomprehensibility of the Deity, differ from sceptics or atheists, who assert that the first cause of all is unknown and unintelligible?” The result could be Ludwig Wittgenstein’s position: “A nothing would serve just as well as a something about which nothing could be said” (Philosophical Investigations, pt. 304). The experiences could not be evidence of any reality—there could be nothing to say to support any claim or its denial. William James’s characteristics of mystical experiences as both ineffable and cognitive (1958: 380–81) would conflict. Nor could different experiences be compared. Nor could what is experienced in one mystic’s experience be identified with, or differentiated from, what is experienced in another’s. But the fact that mystics, both theistic and nontheistic, still distinguish what is an appropriate description from an inappropriate one indicates that what is experienced has some distinctive character and that mystics believe that they have experienced it. That is, something is retained from even the depth-experience that is free of all differentiation, and thus these experiences are not ineffable in this strong sense.

In this way, the mystics’ use of “ineffability” is different from more usual uses of the term. It is not simply hyperbole or an expression of the emotional power of these experiences but something more substantive about its mode of existence. However, what is experienced is not literally “ineffable.” The mere fact that it can be labeled “ineffable” trivially means that it is something in some sense that can be experienced. If such realities were not experiencable at all and thus absolutely unknown, there would be no experiential basis to believe that they existed or to say that they are “unknowable” or “ineffable.” But to say “x is ineffable” means there must be an x that is experienced. Or as Augustine said, God cannot be called “ineffable” because this makes a statement about him. As the fifth-century Indian grammarian Bhartrihari put it: “What is sayable (vachya) by the word ‘unsayable’ (avachya) is made sayable by that word.” Many philosophers think that this defuses the problem of ineffability: to say “x is indescribable” is to describe it, and hence it is not ineffable.5 But more remains to the issue here. Ineffability in mysticism should be understood in another sense: as highlighting the wholly otherness of what is experienced—i.e., nothing phenomenal can be predicated of what is experienced, and so it cannot be expressed. In short, mystics are simply claiming that a reality lies outside the domain of phenomenal predication.

Thus, a problem with language is present for both extrovertive and introvertive mystics. To extrovertive mystics, the conceptualizations crystalized in language come to stand between us and what is real, and so the conceptualizing mind must be stilled to see phenomenal reality as it truly is: there are no real (i.e., independently existing) entities to be referents of words. But language fixes our attention on the thingness of things and not on their beingness. Naming freezes the flow of reality; it marks off a referent from what it is not and thus separates the continuity of reality into a series of disconnected objects—it gives things a standing distinct from their surroundings. That is, naming cuts the flux of reality up into distinct units when in fact reality is continuous. Terms are reified and reality is reduced to a collection of discrete objects. Language, in short, generates a false world of multiple changeless and independent “real” entities and even makes beingness into a thing among things. To mystics, the conceptual creations embodied in language that we invent and impose on reality are “illusory” and blind us to what is actually real. All this makes language the enemy of extrovertive mystical experiences: it fixes our mind on unreal “things” when what is needed is to see that reality is not so constructed. Conversely, experiencing the flow of an impermanent and connected reality makes the discreteness of any linguistic denotation seem hard to reconcile with reality as it truly is. How could we describe the dynamic and continuous reality that we are part of in terms that are necessarily static and distinct?

With introvertive mystical experiences, the complete ontic otherness of transcendent realities becomes the center of the problem. Hans-Georg Gadamer says that “we can express everything in words,” but mystics question this with regard to transcendent realities. They would insist that to give expression to what is experienced in introvertive mystical experiences changes its ontic nature: it seems to make it of the same nature as phenomenal objects. Thus, transcendent realities are “beyond the domain of language” in a way that phenomenal objects, from quarks to galaxies, are not. To mystics, language creates something false out of what is experienced. Whatever mystics say renders a reality that is not a phenomenal thing into a phenomenal thing for the unenlightened, and hence every assertion must be denied. Mystics want to speak, since something real and profound is allegedly experienced, but how can they do that without making that reality into something like a phenomenal object? How can we express oneness in a dualistic language? How can an Advaita sentence have the word “Brahman” as its object when Brahman is the eternal subject? God is not “invisible,” “unlimited,” or “infinite” because these terms apply to possible phenomenal realities and make God seem like merely an unusual phenomenal object. Indeed, if “existence” applies to things in the phenomenal world, how can we even say something transcendent “exists”? How do we say it is real and not “nonexistent” without admitting some terms that apply in the phenomenal world also apply to what is transcendent? If a transcendent reality’s mode of existence is wholly different, how does even the worldly term “is” apply? That is, how can even formal concepts (e.g., “it exists”) rather than substantive ones about its nature apply? Conversely, how could even “nonexistent” or “is not” apply, since these terms depend on terms for phenomenal objects? Thus, is not even the via negativa ruled out? Or how can names or pronouns apply? Whenever we talk about something real, we talk about an it, which is ipso facto wrong since this makes “it” into an object. Any pronoun—male, female, or neuter—makes transcendent realities into objects. Doesn’t referring to the Way make it an object? So too, if a transcendent reality is utterly unique, then terms applicable to anything else cannot apply. Does this not mean that all substantive characterizations, no matter how abstract (“beingness,” “immutable,” “real”) are necessarily wrong since all our terms are derived for things within the natural realm? The problem of the ontic otherness of transcendent realities is supplemented by the problem of the necessity of another mode of consciousness to experience it. Whenever we say anything about what is allegedly experienced, we are in the wrong state of consciousness to know that what is said is true. Any attempt to “grasp” or “conceive” a transcendent reality makes it into something it is not, and hence is a losing battle.

However, both the extrovertive and introvertive problems can be resolved if we consider an error in our common understanding of how language works. The problem is not that language necessarily differentiates items, but the implicit assumption that grammatical status dictates the ontic status of the referents. That is, we go from the fact that denoting terms are distinct to believing a world of Humean “loose and separate” entities, each real and independent. Of particular importance, because we have such terms as “I,” “me,” and “mine,” we tend to believe in a distinct entity that corresponds to them—otherwise, why would there be such terms? In Sanskrit, the word for noumenal self—atman—started as simply a reflexive pronoun. Bertrand Russell believed that the whole idea of substantive entities arose in that manner: “ ‘Substance’ … is a metaphysical mistake, due to the transference to the world-structure of the structure of sentences composed of a subject and a predicate” (1945: 202). Indeed, even saying “Nothing exists”—rather than saying “There is nothing real”—seems to make nothing into a something (and philosophers are indeed puzzled by that). It would be absurd to maintain that words about water must be wet or that the word “big” cannot refer to bigness because it is small, but believing that static concepts cannot in principle apply to dynamic reality or that applying a name or attribute to a transcendent reality “imposes” an ontic “limitation” upon the referent or fundamentally changes its nature is only a short step away.

Under this view, for knowledge-claims to be accurate or useful, there must be a correspondence between reality and words or statements in the sense of mirroring. This leads to a correspondence theory of truth: true statements mirror the differentiated facts in reality. According to Arthur Danto, every metaphysical system he knew presupposes that the deep structure of language and the world share the same form (1973). Certainly Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-philosophicus with its “picture theory” of language is a classic case: there is a shared logical form between the linguistic structure of statements and the structure of reality on the level of facts, and this structuring itself cannot be expressed. Language is a picture of the logical structure of reality; each element of a statement corresponds to an element of our world (Prop. 2.15), but this structure cannot be pictured because it is not itself an item in the world.6 The mirror theory is apparently implicit in early Indian philosophy concerning language for the phenomenal world (see Bronkhorst 2011). The Indian grammarians Jaimimi and Bhartrihari basically used the mirror theory to defend the Vedic worldview. The mirror theory is also behind the claim that in Buddhism final truths cannot be stated but are beyond words, and also behind Dignaga’s claim that words do not refer to anything in the world.7 The opposite of a metaphysics of “atomic facts” can also lead to a type of mirror theory—i.e., going from the fact that language is an interconnected fabric of terms operating in relation to each other to the conclusion that what is designated must also be interconnected. So too, in China the early Daoist Zhuangzi saw the nonfixity of nature reflected in the changing meaning of words (Zhuangzi 2).

To the Buddhist Nagarjuna, people who accept the notion of self-existent entities believe that language reflects the nature of things: if we have a word for something, then it is an independent, self-existent part of the world (Vigrahavyavartani 9). On the other hand, in his metaphysics the interrelation of concepts shows that no entity (bhava) or factor of the experienced world (dharma) is real because they lack anything that would give them self-existence (svabhava) (Mula-madhyamaka-karikas 1.10, 13.3, 24.18–19). That is, we project conceptualizations (kalpanas) unto reality and then discriminate out fictitious “real” entities and become attached to them. Only by undermining all mental props can we be freed from the suffering we cause ourselves by taking this fabricated world to be real. But reality as it truly is (tattva) is free of all conceptual projection (prapancha), and nirvana is simply the cessation of such projection (ibid.: 18.9, 25.24). In short, nirvana is the cessation of seeing the world as constructed of multiple independent entities based only on our conceptualizations (see Jones 2014b: 136–44, 151–57, 162–63).

For the enlightened, the result is a form of linguistic antirealism. No “thing” is designated by language. The problem is that there are no self-contained, “real” things for terms to denote—there is thus no match of categories and reality. In short, language cannot map what is actually real. It cannot “capture” the flux of reality, and we distort reality if we start thinking in terms of distinct permanent “entities.” Nevertheless, language is not meaningless or useless. It still works as a tool for directing our attention and for navigating through the impermanent configurations within the phenomenal world. The Zen analogy of language as merely “a finger pointing at the reflection of the moon in a pool of water” accepts that there is in fact a moon and that we can direct attention to it by pointing. The lesson is simply not to get attached to the pointing finger, let alone mistake it for the moon, but to follow the direction indicated. Some terms work better than others because of what actually exists in the world. Saying that words are mere “names” or “designations,” as Buddhists do, does not change the fact that something real in the world can be “designated.” The word “moon” works in the analogy only because there is in reality a moon (albeit not an independently existing or permanent entity) being reflected in the pool that we can refer to. But mystics remind us that we should not get caught up in the words and thoughts—they are no substitute for what is real.

The same problem occurs for introvertive mystics. To speak of a “mystical union” surely would lead the unenlightened to think of God as a distinct object and a mystical experience as a fusion of two entities. So too with the language of “touching” or “grasping” God. To Shankara, Brahman is the sole reality, and thus terms from the phenomenal realm cannot apply for many reasons: the real is simple and has no attributes to describe; the real is unique and so terms capable of describing anything else could not apply; and no phenomenal (“illusory”) attributes could apply to the real. The problem with transcendent realities is not merely the reification of abstractions into concrete entities—another byproduct of the mirror theory—but the transformation of their ontic status. Mystics speak of transcendent realities as more than subjective, and we normally think there is only one alternative: externally existing real objects. The idea of any referent is that there is an object in the world: if God is not a thing, then he is a no-thing—i.e., nothing—and so does not exist. Transcendent realities are ontologically incommensurable with any results of dualistic awareness, and any words may be taken as indicating such realities’ ontic status—i.e., the realities are automatically reduced to differentiated objects among other phenomenal objects. Thus, for Laozi the Way is nameless (wuming) and cannot be named (Daodejing 1, 32, 37). The Way that can be told is not the eternal Way; the name that can be named is not the eternal name (ibid.: 1). That is, what can be spoken of, even when discussing the Way, is different in nature from the Way. The Way is formless and beyond the senses and comprehension and thus cannot be named (ibid.: 14). Names only come into play with the opposition of objects (ibid.: 32), i.e., when we are aware of opposites such as “beauty” and “ugliness” or “good” and “bad” (ibid.: 2). But the Way is an “uncarved block” that is prior to all opposites and thus free of all names (ibid.: 2, 43).

But again, the copious writings of mystics from around the world indicate that enlightened mystics do continue to speak. If talking about transcendent realities or the phenomenal realm as it really is distorts their nature, why speak at all? Because of the importance mystics attach to their insights. But how can mystics speak at all about what they experience? Because after introvertive mystical experiences and even during extrovertive mystical experiences, they sense diversity. That is, the enlightened state is not an undifferentiated awareness, and in that state it is possible to use language. But when introvertive mystics are in even mindful states of consciousness with differentiated content, their minds make transcendent realities into objects. Plotinus spoke of afterward seeing an “image” of what is experienced, but he makes it clear that this seeing (which must involve duality) is distinct from being “oned” (Enneads 6.9.11). Such images, like all images, are necessarily objectified: some mental distance exists between the perceiver and the perceived. But transcendent realities are wholly other than any objectified conception and hence are unimaginable. Thus, the “One” cannot be grasped by any thought (ibid.: 5.5.6, 6.9.6).

Nevertheless, they succeed only if mystical cognitive utterances can refer to transcendent realities and the phenomenal realm as it really is without distorting their ontic status. But this is possible: we can reject the mirror theory of language without rejecting language. And this appears to be what mystics implicitly do in practice, even if they do not realize it. To cite the Theravada canon, the enlightened can make use of current forms of speech without “clinging” to them or being led astray by them (Majjhima Nikaya 1.500, Digha Nikaya 1.195). Thus, the Buddha could use “I” (aham) and first-person verbs without believing in a separate and real self—“I” is merely a useful shorthand for one constantly changing bundle of aggregates in the flux of phenomena. The prime illustration in the Theravada tradition is the word “chariot” for the temporary and changing parts assembled into a working chariot (Milindapanha 2.1.1). In the Prajnaparamita tradition, bodhisattvas too can use language, although the results are sometimes strange. For example, Subhuti can say, “I am the one whom the Buddha has indicated as the foremost of those who dwell free of strife and greed [i.e., an Arhat]. And yet it does not occur to me ‘I am an Arhat, freed of greed’ ” (Diamond-Cutter Sutra 9). That is, Subhuti could accept the description of himself as “an Arhat” and say the words “I am an Arhat,” but he does not see this as indicating a distinct, self-existent entity. Denotative words and statements are now taken not to refer to permanent objects but to fairly stable configurations in the flux of phenomena that we group together for attention. These “conventional designations” can still indicate what is “conventionally real,” although from the point of view of the highest concern (paramarthatas) the conventional is ultimately empty of permanence and thus is not real. That is, Buddhists affirm that there are denotable factors of the phenomenal world (dharmas)—dharmas simply lack the independence of being self-existent.

In short, what has been implicitly rejected is only the mirror theory of how language works, not language itself. That is, using language does not itself entail any ontic commitments—only a theory of the nature of language does—and we can reject the theory and still utilize language. Thus, the word “God” can be a grammatical object even though theists do not treat God as a phenomenal object or as a transcendent object set against the phenomenal world. But this means that how the enlightened view concepts has changed. They see language about the phenomenal world as useful for negotiating the world and for leading others toward enlightenment even if there are no permanent referents for nouns in the ultimate makeup of reality. (And since the enlightened do speak, we cannot dismiss all mystical statements as products of ignorance and therefore false. This also means that the enlightened should have no problem talking to each other.) This is possible since there are configurations in the flux even if they are only temporary: buildings may only be impermanent assemblages, consisting of equally impermanent parts and not “entities” unto themselves—and thus are not “real” in that specific sense—but the word “building” is still useful for directing attention to parts of the present flux of reality as we move through the world. Buildings do not exist in a way different than how Santa Claus does not exist—there is some reality there even if the reality is constantly changing and thus there is no permanent referent for any term. Different languages make different distinctions, but all languages must make distinctions and categorize things. Thus, there is no reason for mystics to try to invent a new language since all languages present the same basic problem of dividing the indivisible and labeling transcendent realities as things. Mystics can simply employ the language of their own culture; their only change may be to use the passive voice more than the active one. But the enlightened now use language without projecting the linguistic distinctions onto reality and creating a false ontology of unreal distinct “entities.”8

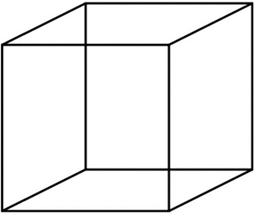

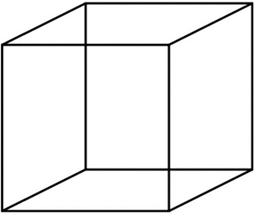

We can see the introvertive mystics’ dilemma by means of an analogy that parallels the situation in one important respect. Imagine beings who experience the world only in two dimensions. Now imagine claiming to them that three-dimensional objects exist. They cannot form mental images of three-dimensional objects any more than we can form images of four-dimensional objects. Perhaps some of them will accept the possibility of such objects even if they cannot picture one, just as we can accept the existence of colorless objects such as atoms even though we cannot picture them without adding a color. Now consider drawing the two-dimensional Necker stick drawing of a cube for these beings, and the problem of trying to explain it to them.

This is a mixture of correct and misleading information—the straight lines and number of vertices reflect the cube, but the angles are not all 90 degrees, and some edges intersect. More importantly, the drawing distorts the cube’s basic nature by omitting a third dimension. Being forced to draw in two dimensions introduces this omission and these inconsistencies, but there is nothing we can do about it. We might add more detail by shading some sides, but this will not help since the hypothetical beings still cannot imagine a third dimension. And any verbal description will sound odd to someone who has never seen a real cube: “All the angles are really the same, and it is not ‘flat’ (a term that may have no meaning to these beings), and the six sides are all the same shape and touch only on the outside.”

We might even conclude that the cube is ineffable since the drawing seems to distort what it really is like and changes its nature from three dimensions to two. But the drawing is in fact an accurate representation as far as it goes—we simply need to realize that it is only a drawing and that there is a dimension not conceptualizable in “two-dimensional language” the way two-dimensional objects are. But most importantly we need the experience of actually seeing and handling a cube to see how the drawing is correct. The drawing cannot convey its own flatness: the missing third dimension cannot be captured by a drawing. Thus, studying the drawing is no substitute for experiencing a real cube. Those beings who are sympathetic may come to understand that the drawing is not the cube, and thus they would not assimilate the drawing to their normal reactions. Nevertheless, without actually experiencing a cube, they cannot know why this drawing and not others is appropriate and in what sense it is accurate. Only with such an experience will the odd and contradictory features be understood in a nondistortive manner. Without it, the drawing is like M. C. Escher’s drawing of four waterfalls flowing into each other—something that can be drawn but cannot correspond to anything in the real world.

This predicament parallels that of introvertive mystics in one way: since the unenlightened do not have the requisite experiences, they can do no more than reduce any talk of transcendent realities to a kind of unusual phenomenal object. Because of the linguistic “drawings,” transcendent realities are relegated to the status of a familiar phenomenal object. And because the “drawings” seem impossible and contradictory, many reject the possibility that transcendent realities can be real. But just as some of the features of the cube are captured by the drawing (the six sides, straight edges, eight vertices, and some angles) and the drawing overall is accurate if understood properly, so too linguistic descriptions of a transcendent reality can be accurate if we reject the mirror theory of language: mystical statements do not falsify, but we need a mystical experience to see properly how they apply and are correct, and even to understand the claims properly. Some features of transcendent realities (nonduality, realness, immutability, transcendence of the phenomenal realm) are accurately conveyed if we overcome the tendency to project grammar onto reality. This mixture of correct depictions with distortive possibilities accounts for the mystics’ hesitancy to affirm the adequacy of any conceptualizations of transcendent realities. Again, the problem is not remedied by introducing a new language—a different map projection, as it were—since all languages are dualistic and thus cannot mirror the ontic nature of what is nondual.9

Having a mystical experience reorients how we understand mystical cognitive utterances, just as seeing a cube reorients how we see the drawing. The language is no longer as confusing, but it remains the only way mystics could convey anything about what was experienced. The ontic status of transcendent realities is not “captured” by any language, and their mode of existence would be altered by the unenlightened, but the enlightened can use language free of the metaphysical mistake to convey some alleged knowledge of alleged realities, just as we can draw the cube without being misled by the distortive aspects of the resulting drawing. (If mystics can see the “drawingness” of their “drawings,” they may become less attached to the prevailing concepts and symbols of their culture.) And those without mystical experiences can come to understand something of what mystics are saying (and even to distinguish accurate descriptions from inaccurate ones) by following analogies and seeing what is negated. But without having the experiences the unenlightened’s understanding will always remain tainted.

Thus, the mirror theory explains the problem labeled “ineffability.” The experience is not vague or nebulous—it is a bright light. The problem of putting what was experienced into words after the experience revolves around the fact that words will make the reality experienced into a phenomenal object, which it is not. This leads to the paradox of mystics denying that language applies to what is experienced and yet continuing to talk about it. Mystics can acknowledge the “wholly otherness” of what is experienced and yet can also deny that it “defies expression” if they reject the mirror theory.10 The language used is as adequate as any denotative language is if we can reject the mirror theory of how language operates.

There are four responses mystics can make to their dilemma with language. Two involve adhering to the mirror theory (silence and negation of all characteristics), one implicitly rejects it (positive characterizations), and one combines the two (paradox). Paradox will be discussed in the next chapter.

If the mirror theory were strictly adhered to, the result for introvertive mystics should be silence about mystical realities.11 But the silence of mystics is the opposite of the silence of skeptics: it is based on knowing something that cannot be expressed adequately. Plotinus claimed that all predicates must be denied: even “the One” does not apply to what is transcendent since “one” is a number among numbers, and thus it may suggest some duality; silence is ultimately the only proper response (Enneads 5.3.12, 5.5.6, 6.7.38.4–5). As already noted, even “is” would not be applicable to transcendent realities or the phenomenal realm as it really is since phenomenal objects are. So too, vice versa: if only the alleged transcendent reality is deemed real, we cannot say that worldly phenomena exist. In Buddhism, only reality as it truly is (tattva) is real, and so the differentiated phenomena of the world cannot be said to “exist.” So too with Advaita for Brahman and the “dream” realm.

Mystical silence is not merely not speaking but also inner silence—i.e., not even any thoughts about the transcendent. No words seem applicable. Treating “the Way” or “the One” or “Brahman” as names does not solve the problem. Plotinus tells us that it is precisely because the One is not an entity that “strictly speaking, no name suits it” (Enneads 6.9.5). (To the Neoplatonist Plotinus, names are like Platonic “forms” rather than simply conventional labels we apply to things.) Indeed, Eckhart said that by not being named, we named God (2009: 219). According to Shankara, the idea of Brahman as an entity is superimposed (adhyasa) on the name “Brahman” (Brahma-sutra-bhashya 3.3.9). Laozi’s distinction between a “private name” (ming) and a “public name” (zi) (Daodejing 25)—i.e., “the Way” is used only in the first sense since there is no public name for it—does not get around the problem: private names still mark off an object.12 Similarly, even if Nagarjuna is referring to “dependent-arising” (pratitya-samutpada) as merely a “designation” (prajnaptir) (Mula-madhyamaka-karikas 24.18), this does not help. Neither does treating “God” as merely a placeholder for the mystery experienced in theistic experiences. In short, language appears under the mirror theory to be a Procrustean bed, and so what is experienced is declared ineffable.

Shankara quotes from a now unknown Upanishad the case of Bahva, who when asked to explain the self said “Learn Brahman, friend” and fell silent. When the student persisted, Bahva finally declared: “I am teaching you, but you do not understand: silence is the self” (Brahma-sutra-bhashya 3.2.17). Here silence itself becomes the thing known, not merely a part of the meditative techniques to attain mystical experiences: the inner silence does not merely reflect the mystic’s mental state resulting from stopping the noise of the discursive mind, but indicates the nature of a transcendent reality. Brahman is silent, as Eckhart also says of the transcendent ground (McGinn 2001: 46). And by Bahva speaking of silence in this way, the problem with language is reintroduced. Also notice that Bahva did not remain silent for long. Silence here is a teaching technique, and teachers seldom end up taking a vow of silence. The same is shown by the tale known as the first Zen story of the Buddha silently holding up a flower and only Kashyapa understanding. The Buddha too did not remain silent but extensively taught verbally. The Buddha was called “the silent one of the Shakya clan” (shakya-muni), but this referred only to his training on the path; in the enlightened state, he was “silent” only in the technical sense (following the mirror theory) that words are not real and thus he did not utter a “real” sound when he spoke. This also means, as Madhyamikas emphasize, that there is nothing real (sat) to teach and that the Madhyamikas advance no theses (pratijnas) (e.g., Mula-madhyamaka-karikas 25.24) since nothing is self-existent.

Silence protects both the experiences themselves and the reality experienced. But it is hard to remain silent about something that mystics consider fundamentally important. In Jalal al-din Rumi’s words, “There is no way to say this, … and no place to stop saying it.” Indeed, claiming that one must be silent only enhances the otherness and importance of an alleged transcendent reality. Moreover, our analytical mind’s innate tendency to conceptualize takes over after introvertive mystical experiences. Both mystics themselves and the unenlightened want to know what the mystics are being silent about. Hence the paradox of ineffability: in order to claim that a transcendent reality is beyond all names, we must name it. Merely saying that there is something “transconceptual” is not itself to form a conception of anything, but in our unenlightened state we will form a mental object for thinking about “it.”

The extreme opposite of silence is the affirmation of some positive features of transcendent realities. In Christianity, affirmative theology is called “kataphatic,” from the Greek “kataphasis” meaning “speaking with.” And mystics do ascribe positive properties to transcendent realities—if nothing else, they are “real,” “one,” and “immutable,” even if such abstract properties may not be very helpful to the unenlightened. Indeed, mystics may believe that what was experienced is profoundly significant and yet have only flat platitudes to say about it. But if absolutely no features were given in mystical experiences, there would be nothing retained and nothing to express or to deny. But from what is retained, some descriptions are more accurate than their opposites, although the danger remains that, due to the mirror theory of language, the unenlightened will misunderstand the nature of the ontologically incommensurate transcendent realities. Still, some concepts and statements are better or more appropriate in the sense that if these realities were phenomenal objects, they would be denoted by those concepts and statements in the same way phenomenal objects are denoted. For example, transcendent realities are “one” and “real,” not “multiple” or “apparitions.” So too, if a god exists, it is “personal,” not “nonpersonal” or “unconscious.” Thus, some descriptions reflect better what was experienced, but since any “image” is in the same class as images of objects while transcendent realities are ontologically different, any descriptions of what was experienced is held to be distortive. For example, Plotinus used “one” only to contrast the One with multiplicity, but even “the One” only indicates a lack of plurality, not one object among objects. “One” is used to start the mind toward simplicity, not to designate one thing among many phenomenal objects (Enneads 5.5.6), since any property is a characteristic of the universe’s being, not of the One (the source of being).

The problem is that all images are formed in the same way while transcendent and phenomenal realities are ontologically distinct.13 Certainly any analogy of proportionality—e.g., human goodness is to us as God’s goodness is to God—reduces a transcendent reality to an unusual but still phenomenal object, since it would make such a reality in effect an item in an equation.14 We will always react to any alleged feature in terms of our normal understanding of things. Such a danger is present when using any concept or imagery with which we are familiar. God is experienced as a reality personal in nature, and so some personal imagery is appropriate.15 But using personal images can easily lead to a crude anthropomorphism (i.e., making a transcendent god into a copy of a human being): we quite naturally read in features from our own culture and time of what we consider an ideal human person to be and so end up ascribing our way of thinking and feeling to God—e.g., he loves what we love and hates what we hate. Thereby, we end up projecting human qualities without any experiential basis and end up with an entity that is the product of our imagination. Any images of a being can lead to other forms of idolatry by reducing a transcendent reality to a phenomenal reality or by associating anything worldly with God. Familiar images have to be used, but the danger is that our attention is directed away from the transcendent referent to the worldly phenomena of the image itself. So too, the Christian practice of giving symbolic interpretations to biblical passages may not be an effective mystical strategy since it may only plant our normal frame of reference more firmly in our mind: when Eckhart sees Jesus cleansing the temple of moneychangers as a symbolic statement of cleansing the soul of all images, listeners will now be thinking in terms of Jesus and the temple. We may also read too much from a metaphor into a transcendent reality, since the unenlightened do not have the experience that shows how the metaphor is used. More generally, the mixture of applicable and inapplicable aspects of any metaphor to transcendent realities keeps them from being accurate representations in toto of any such realities.16

The strategy that mystics employ to avoid this possible reduction of transcendent realities to phenomenal objects is to maintain that positive descriptions merely “point to” rather than directly or literally “describe” the realities. Plotinus said that we can speak of “the One” only to give direction—to point out the road to others who desire to experience it (Enneads 6.9.4). Shankara says that the positive characterization “truth/reality” (satya) cannot denote Brahman but can only indirectly indicate it (Taittiriya-upanishad-bhashya 2.1.1). Words do not properly “describe” or “signify” Brahman but “imply” it or “direct our attention” toward it (ibid.: 2.4.1, Brahma-sutra-bhashya 3.2.21). So too, the word “self” (atman) is qualified by “as it were” (iti) to indicate that the word does not actually apply (Taittiriya-upanishad-bhashya 2.1.1, Brihadaranyaka-upanishad-bhashya 1.4.7). Plotinus likewise noted that we need to add “as if” when speaking of the One (Enneads 6.8.13). One of Shankara’s disciples, Sureshvara, said that Brahman is indirectly signified just as the statement “The beds are crying” indirectly indicates the children who are lying on them. But he conceded that this type of suggestiveness based on literal meaning only inadequately implies the self, since whatever is used to refer to the self becomes confused with it (also see Shankara’s Brahma-sutra-bhashya 1.2.11, 2.1.17).

The problem of potential distortion persists whether the positive features that are ascribed are abstract (e.g., “oneness”) or more relatable imagery (e.g., God as a shepherd, or the One as a “wellspring”). But both classes are broadly metaphoric in the sense of using a term with an established meaning concerning phenomenal objects to direct attention to something else.17 Even if mystical experiences are quite common, metaphors are still needed because transcendent realities are ontologically distinct and so concepts that apply to phenomenal realities must have their meaning extended to something different. As the medieval English author of The Cloud of Unknowing wrote concerning the use of spatial terms to indicate transcendence (“up,” “down,” and so on), the terms are not meant literally but “as human beings we can go beyond their immediate significance to grasp the spiritual significance they bear at another level” (Johnston 1973: 128). Many in philosophy argue that all language is metaphoric and that metaphors permeate our thought, but the above mystical passages suggest that these authors assume there is a literal use of terms in addition to a symbolic use—that calling a man “a lion” is different from calling a lion “a lion.” That is, these terms have established meanings and apply literally when phenomenal objects are the referents.

However, if transcendent realities are ontologically totally distinct from the phenomenal world, how could anything from the latter realm be used even symbolically to refer to the former? The answer must be that mystics see some similarities in the properties of the ontologically incommensurable realities. For example, God is ontologically incommensurable with created human beings—to Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite he is beyond (hyper) human nature—but God and human beings share properties that enable both to be called “personal” or “conscious.” That is, God is more like our personhood than a nonperson and more like our consciousness than what is nonconscious. In short, transcendent realities and worldly phenomena are ontologically disparate in their ontic natures, but this does not preclude them being alike in some properties. Without such commonality, there could be no good reason why certain concepts and images are more appropriate than their opposites or other images. As the cube and its drawing have some features in common even though their modes of existence differ, so too some features of the phenomenal world share properties with transcendent realities and so can be used to explicate something of transcendent realities. This is why “one,” “immutable,” and “real” are more applicable than their opposites. God is “personal” in nature because he is experienced that way, but he is not a being like a human being is—he is simple and without differentiable features (thus giving rise to the theological problem of how what is simple can have numerous properties).18 Otherwise language could not function even figuratively to refer to something one is not familiar with.

So too, symbols are not true or false, but any symbols indicating a source (“ground,” “womb,” “abyss”) are more appropriate and useful than symbols indicating a product, just as a loving God is more like a “shepherd” than a “wolf.” Symbols from different cultures and eras will differ and may change, but the experienced reality would remain the same. And the problem always is that the unenlightened will construe the terms literally, and, since they have not had the necessary experiences, they may not be able to follow them well enough to understand mystical claims about transcendent realities. Terms we use get their meaning first in applying to nonmystical realities, but even if some new terms were invented for referring only to mystical transcendent realities, the unenlightened would still think in terms of phenomenal realities and the terms could still be used mystically only by a metaphoric extension. Theists using old terms (“thy” and “thou”) and arcane word order may point to the otherness of God, but beyond that this does not help. This problem would occur even if poetry, music, or nonrepresentational visual art is used: it may open us to transcendent realities, or our unenlightened mind may still think in terms of phenomenal realities.

The congruence of transcendent and phenomenal properties is the basis for claiming that mystical utterances state cognitive claims about a transcendent reality. Even if all mystical utterances have a metaphorical component, the experiences can still provide the foothold needed to make the statements meaningful. As mentioned in chapter 3, in an analog to the causal theory of reference for scientific claims, what is experienced in theistic or nontheistic mystical experiences can be seen as grounding the cognitive utterances despite changing symbols and conceptions. It would be like the seeing and handling of a cube grounding drawings of the cube. No literal statements—i.e., statements that do not need a metaphoric extension—would be required to ground meaningfulness.19 The “sense” of the reality may be specifiable only through changing and limited metaphors, but the referent does not require literal depictions if the reality can be experienced directly.

But again, because of the ontic difference between the world and transcendent realities, mystics must always stretch everyday concepts and images. Plotinus’s figure of the One as an ever-full spring shows the problem. We know what a spring is, but how are we to understand a spring that has no origin, is never emptied, is ever-flowing, and yet always full? Perhaps we can mentally extrapolate the everyday properties into infinite ones, but we would still be thinking in terms of phenomenal objects with infinite properties. Positive remarks will always be limited in that regard. So too with more literal, nonfigurative descriptions. We know how material objects “exist,” but how do transcendent realities “exist”? An analogy such as the dreamer being “more real” than the characters in the dream and being the source of whatever reality the dream characters have can only take us so far in understanding how a transcendent reality exists and is a source. So too with the Advaita image of the world as a magical illusion (maya) to show its lack of independent existence and its outwardly deceptive character.

This highlights the problem of whether nonmystics can understand mystics when mystics give positive characterizations. Whether such utterances are meaningful to the unenlightened ultimately depends on whether the metaphoric discourse supplies a meaningful mystical content to them. Arguably such discourse does. The unenlightened can understand the point of a metaphoric utterance well enough to understand mystical claims even if they do not know exactly how it is applicable and why it is appropriate. But as David Hume said, a blind person can form no notion of color or a deaf person of sound. So too here: the unenlightened cannot stand in the shoes of mystics. But mystics form appropriate conceptualizations of what they experienced after their experiences, and nonmystics may be able to follow these statements and images in the direction of transcendence. Understanding any mystical use of metaphor requires some imagination. Sympathy for what mystics are trying to do is not enough. The unenlightened will always be stuck having to rely only on their nonmystical understanding of the terms. Any metaphor used to communicate something beyond what the listener has already experienced only becomes clear once the intended experience has occurred. Mystics can do no more since a new experience is required to reorient the sense and use of the images and concepts. Thus, there are limits, but following the analogies and metaphors in the direction of transcendence (i.e., away from the phenomenal world via, for example, the “dream” analogy) seems sufficient to make mystical utterances minimally intelligible to the unenlightened.

This also raises the question of whether the normal meanings of terms are transformed in attempts to denote transcendent realities. The drawing of the cube points to a three-dimensional cube, but the drawing works only if we uproot the implications that a two-dimensional object is involved, and the same is true with mystical utterances. In effect, a concept or statement is emptied of its normal denotation and filled with one given in a mystical experience. Does this mean that, for example, “good” means something different when mystics say that God is good? But if God’s goodness is utterly unlike ours, then the term “good” does not apply and we have no idea what God is like in this regard. Mystics often say things that suggest that the transcendent’s properties are so different that the phenomenal meaning of the terms does not apply. As Eckhart said, God is not “good,” “better,” or “best,” or “wise” (2009: 463). But if this is more than simply hyperbole, there is a problem: only if the meaning of the terms remains the same can any analogies or metaphors work, just as some features of the drawing of the cube (e.g., the straight lines) remain the same in the cube itself. If our terms do not apply to the new subject, we are consigned to silence. Even “exists” or “is” could not be used.

However, if the mirror theory of language is rejected, mystics do not need to take that route: terms for worldly phenomena could be used while stressing the wholly other ontic nature of transcendent realities without any change of meaning. For example, theists can affirm that a transcendent reality is personal in nature: God may be “transpersonal,” but he was some personal quality in the human sense. So too, God’s and humans’ goodness are alike in some way, even if God’s is greater and purer. Similarly, the words “exists” and “is” mean the same for transcendent realities as for phenomenal ones even though their modes of existence differ. The problem, in sum, is not the literal meaning of the terms when it comes to transcendent realities, but that these realities are not phenomenal objects and that only by a mystical experience can we see how the terms apply.20

The primary way that introvertive mystics counter such positive characterizations is by negating any possible characteristic of transcendent realities since such realities are unlike anything phenomenal. Hence images of “darkness” and “nakedness.” In a remark echoed by Augustine about God, Plotinus said that we can state what the One is not, not what it is (Enneads 5.3.14). To Shankara, words like “Brahman” and “self” are superimposed on the real (satya) since describing the real without recourse to limiting adjuncts (upadhis) is an “utter impossibility” (Brahma-sutra-bhashya intro., Brihadaranyaka-upanishad-bhashya 2.3.6). But he asserted that all “positive” characterizations of Brahman—reality, knowledge, and infinity—are only meant to remove other attributes: Brahman cannot be the agent of knowing, for that requires change and denies reality and infinity; knowledge merely negates materiality; and reality and infinity negate knowledge (Taittiriya-upanishad-bhashya 2.1.1). It is all a process of negation (apavada). And since the real is in fact free of all differentiations, we are left with describing it as “not this, not that” (neti neti) to remove all terms of name, form, and action. More generally, mystics want to say that “human language”—as if there were another kind—does not apply and so must be negated.

Thus, mystics are major advocates of the via negativa—the denial of any possible positive description of the transcendent. In the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, brahman/atman is famously described as “not this, not that” (2.3.6, 3.9.26, 4.2.4, 4.4.22, 4.5.15), thereby denying all features to it. So too, as discussed in the next chapter, the Buddha denied that any concepts concerning existence “fit the case” of the state of the enlightened after death (Majjhima Nikaya 1.431, 2.166). Affirming any option—the enlightened “exists,” “does not exist,” “both exists and does not exist,” or “neither exists and does not exist”—would show a misunderstanding (since these terms apply only to dharmas and after death the enlightened have no dharmas) and give a mental prop to which we may become attached (Samyutta Nikaya 4.373–402). Buddhists later developed a theory of meaning based on excluding what is not intended by a word. The via negativa approach was introduced into the Western theistic traditions through Neoplatonism. Plotinus said no words apply to the One (Enneads 6.8.13). For example, the One cannot be a “cause” since that term applies to phenomenal actions. He repeated this regarding “the Good” and even “the One” (ibid.: 3.8.11.12–13, 5.5.6.22–23). Any property is a characteristic of being, not the One, and so all properties must be denied (ibid.: 6.9.3). Eckhart said that God is “neither this nor that”—God is a nongod, a nonspirit, a nonperson, a nonimage detached from all duality; he is not goodness, being, truth, or one (2009: 465, 342, 287). So too, God is beyond all speech (ibid.: 316–17).

If a transcendent reality is indeed utterly unlike the components of the world, one can ask why negative terms (e.g., nonpersonal) would then not apply. If Brahman is not a person, then the statement “Brahman is not a person” is true. Philosophers, thinking in terms of phenomenal objects, naturally believe that if x is not p, we can affirm the negative statement “x is not-p.” However, problems arise when it comes to mystical discourse. First, mystics may assume that if we affirm the negative claim, the unenlightened will always be thinking in terms of discrete entities (contra extrovertive mysticism) or in terms of phenomenal objects and not be directed toward transcendent realities (contra introvertive mysticism). We could affirm the negation as true, but unless we reject the mirror theory of language it would still be misleading. We can say “The number 4 is not blue,” but to start thinking of numbers in terms of color only directs the mind away from the true nature of numbers. So too with any affirmation of negative characterizations of transcendent realities. The problem again is that a transcendent reality is not a phenomenal object to which the idea of “nonpersonal entity” would apply. The danger is that any negative characterizations would still render a transcendent reality an x—a thing within the world among other things. Thus, mystics would object even if an exasperated philosopher exclaimed “Well, at least Brahman is not a rock!” (And if Brahman is the true substance of all phenomena, then a rock is Brahman.)

Second, if there is only one transcendent reality, it may appear to be, for example, personal in some experiences and nonpersonal in others. Theists will assert that the transcendent-in-itself is personal and only appears nonpersonal in experiences of its beingness; Advaitins will assert the reverse. Thus, to assert that the transcendent is nonpersonal would be to side with Advaita in this dispute on the true ultimate nature of the transcendent and not merely to make a formal remark about the logical status of a reality that is “wholly other.” And Advaitins even object to labeling Brahman nonpersonal: through the mirror theory, this makes Brahman into an entity. Even Brahman without features (nirguna) is a conception from the analytical mind and so does not reflect the transcendent reality-in-itself. This means that the transcendent reality is not personal or nonpersonal: in itself, the reality does not possess contradictory phenomenal properties but is beyond any conception we can devise or its negation. (Also see the electron example in chapter 3 and in the next chapter.) In sum, it is not possible to say that a transcendent reality-in-itself has any phenomenal property or its opposite.

The via negativa thus protects openness and the mystery of the transcendent. It also directs the listener’s mind away from the natural realm. But maintaining a pure via negativa is difficult for mystics—even Zen eventually adopted a more positive approach. It is especially difficult to maintain for theists who see what they have experienced in terms of a moral, caring person. The theologian Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, the father of the via negativa in the Christian tradition, claimed God is ultimately a “divine darkness” beyond any assertion or negation, but he also wrote a book on the symbolism of divine names (although he stressed that God cannot be fully captured by any names). To Shankara, the process of negation leaves something real since we can only negate something by reference to something real (Brahma-sutra-bhashya 3.2.22). Thus, he maintains that there is a real basis to superimposition while asserting that Brahman as an object of thought is a product of root-ignorance, either in the lower form as the god Ishvara (Brahman as qualified) or the higher form (Brahman as the opposite of all qualifications) (Brahma-sutra-bhashya 1.1.11, 1.2.21).

Indeed, for mystics there is always a basic affirmation beyond the negations—a reality that is experienced. Thus, although the via negativa is a movement beyond affirmations, it is never merely a denial—there is a “negation of negation.” Plotinus introduced the notion of “speaking away” (aporia apophasis) in the West, but it was never entirely negative.21 Certainly the reality of a transcendent reality is not denied by theistic mystics, even if it is Eckhart’s “Godhead beyond God.” Rather, the transcendent reality is beyond both the affirmation and negation of worldly attributes. Negation thus may be applied because a mystic thinks what was experienced is so much more than any terms for phenomenal reality could convey. That is, a reality is known but cannot be described because it is greater than anything any description could capture. Eckhart, even while utilizing the word “God,” said that God is nameless because he is “above all names”—if we gave him a name, he would have to be thought (2009: 139).22 So too, saying God is “beyond good” does not mean he is evil; rather, even the label “good” cannot be applied to him because he is so much more. Dionysius said that we attribute an absence of reason and perfection to God because he is above reason and is above and before perfection (The Divine Names, chap. 7). Nevertheless, the negation of phenomenal attributes does indicate the direction of another dimension of reality and thus has soteriological value.

However, one must ask how a “negation of negation” differs in the end from the affirmative approach discussed above, and whether, as Plotinus said, the “sheer dread of holding to nothingness” forces mystics back to the everyday realm of language (Enneads 4.7.38.9–10; see also 6.9.3.4–6). This approach does not deny that there is some positive reality but only emphasizes its otherness and its lack of phenomenal properties and directs attention away from the phenomenal realm. And the basic danger of the mirror theory will remain that the unenlightened will translate anything mystics say into a statement about an object within the world. To say “Brahman is not open to conceptualization” does not conceptualize Brahman, but it involves a conceptualization, and our conceptualizing mind will treat it as any other conceptualization. The danger is of merely separating one object from other objects by the process of negation. We would still think in terms of a phenomenal entity without certain attributes. We would merely attribute a negative property to the new entity, and as Walter Stace (1960b: 134) and others point out, there is no principled way to make an absolute distinction between positive and negative attributes—we still take negation as affirming another property. Even attributing “nonbeing” to a transcendent reality or saying that “it does not exist” still produces an image in the mind of an object set off from other objects. Perhaps this is why Dionysius said that neither affirmation nor negation applies to God (Mystical Theology, chap. 5).

Nonmystical theologians besides Dionysius have also emphasized the via negativa. Thomas Aquinas wrote “we cannot know what God is but rather what he is not” (Summa Theologiae 1a.3). Anselm could make “that than which nothing greater can be conceived” into an object of reasoning and comparison.23 Today books can be written on the via negativa without any reference to mystical experiences (Turner 1995; Franke 2007). Part of this is the postmodern contention that mysticism is nothing but a matter of language, but this also shows that the via negativa is not a device utilized only by those who have had mystical experiences. It can be simply a speculative theological strategy for working out the logic of ideas about a supreme being.

The negative approach has never been the predominant trend in the Abrahamic religions, although it has more prominence in Eastern Orthodox Christianity. Even Muslims, who stress the unknowability of God to all but prophets and mystics, do not emphasize this approach. Theists always attribute positive features to God. In Christianity, in the beginning was the word (logos) (John 1:1), not silence. Theologians try to tame the via negativa by treating it as only a supplement to the positive approach. Mystics, however, see the negative way as a corrective to any positive depictions of a transcendent reality since all attributions must of necessity come from the phenomenal realm. This approach does not merely affirm that there is more to a transcendent reality than is known but affirms its absolute otherness from all things natural. Positive characterizations may direct our attention away from other objects, but this still makes a transcendent reality into one object among objects. The second step—the negation of all positive characterizations—corrects that and directs our attention away from all objects and toward transcendence.

Either claims about realities as experienced by mystics do accurately reflect something of those realities or nothing can be uttered about them—one option has to be rejected. But the usual alternatives—rejecting mystics’ claims as nonsense or rejecting language—can both be discarded if the mirror theory of how language operates is rejected instead. Mystics apparently believe that what they utter is not in vain. Eckhart closed one of his sermons saying “Whoever has understood this sermon, good luck to him! If no one had been here, I should have had to preach it to the offertory box” (2009: 294). This he would have done to proclaim something that he felt to be true and of utmost importance. Mystics also find language to be useful in verifying whether others have had the prescribed experience (by seeing what they say and how they say it) and in guiding others to having mystical experiences. The different strategies with regard to language are meant to direct the unenlightened mind away from the world and toward beingness or transcendent realities. To modify the Zen analogy, assertions about mystical realities are more than a finger pointing to the image of the moon reflected in a pool of water: they are pointing to the moon itself, and it is only the unenlightened who, like those mistaking the drawing for the cube, mistake the pointing finger (the words) for the moon. Advaitins claim that no language can apply to Brahman since all languages involve distinctions and Brahman is nondual and free of distinctions. But while no statement can be a substitute for experience, one in a dualistic state of mind can state such “ultimate truths” as “Brahman is nondual” or “There are no self-existent entities.” To use an analogy: to know that the statement “Drinking water quenches thirst” is true, we need to drink water, but, while the act of drinking “surpasses” that statement, it does not make the statement only “conventionally true” or make the act of drinking “beyond language” or an “unstatable higher truth” in any sense other than the obvious and uncontroversial one that the act of drinking water is not itself a statement.24 Otherwise, mystics could not say anything about the nature of reality, because if they use words they would be ipso facto stating only conventional truths. Thus, mystics would be consigned to silence.

Because of the concern for possible misunderstanding by the unenlightened, it may seem that introvertive mystics want things both ways—that statements and symbols both apply to transcendent realities and do not apply. But the claims to ineffability are only meant to emphasize the “wholly other” nature of transcendent realities to the unenlightened, who may yet misconstrue the nature of the intended realities. So too, with the rejection of any metaphoric statements based on worldly phenomena: claims cannot apply positively or negatively to transcendent realities without unenlightened listeners misconstruing the ontic nature of such realities.

The mystical condemnation of language can be seen as an expansion of the Christian and Jewish prohibitions against creating physical images of God (Exodus 20:4–6) and the Islamic prohibition against the deification of anything phenomenal (shirk) to include all mental images. Such idols of the mind also inhibit having mystical experiences. But if we reject the mirror theory of how language works, language and everyday symbols can be used to reveal at least something true of alleged transcendent realities, even if there must be metaphorical extensions to a new referent and even if we need the requisite experiences to see why these are accurate or appropriate. That all claims must be false and language must be rejected and that we must be resigned to silence is entailed only by accepting the mirror theory.

However, in trying to show how such claims as “The Godhead is empty of phenomenal qualities” may be meaningful to the unenlightened, accurate, and put into words as well as can be expected when dealing with such an alleged reality, the danger remains that we unenlightened folk will still think of transcendent realities in terms of unusual objects akin in their ontic nature to phenomenal objects. Far from aiding in inducing mystical experiences, focusing on how mystical utterances are intelligible may well embed conceptualizations more firmly as acceptable to the analytical mind. If so, this has an antimystical effect, even though mystical discourse must be intelligible to the unenlightened to be helpful. We are still squarely entrenched in the realm of language, and, as the Zen adage goes, “Wordiness and intellection—the more with them, the further we go astray.”