Four

CONSTRUCTION

AND CHANGE

Before construction began on the transformative Wilshire Viaduct project, the local community mobilized to fight the dirt-fill option. According to the Westlake District News, the “mammoth mass meeting” attracted 800 local residents to the Royal Palms Hotel (the building still stands today and continues to host community events) to hear from local community and political leaders regarding their concerns with the proposal that would annihilate “the beautiful tropical scene” of Westlake Park. The dirt-fill option was described as “the most expensive, obnoxious method” proposed. Political leaders present at the meeting promised to fight the proposal until the end. (Courtesy of the City of Los Angeles Archives.)

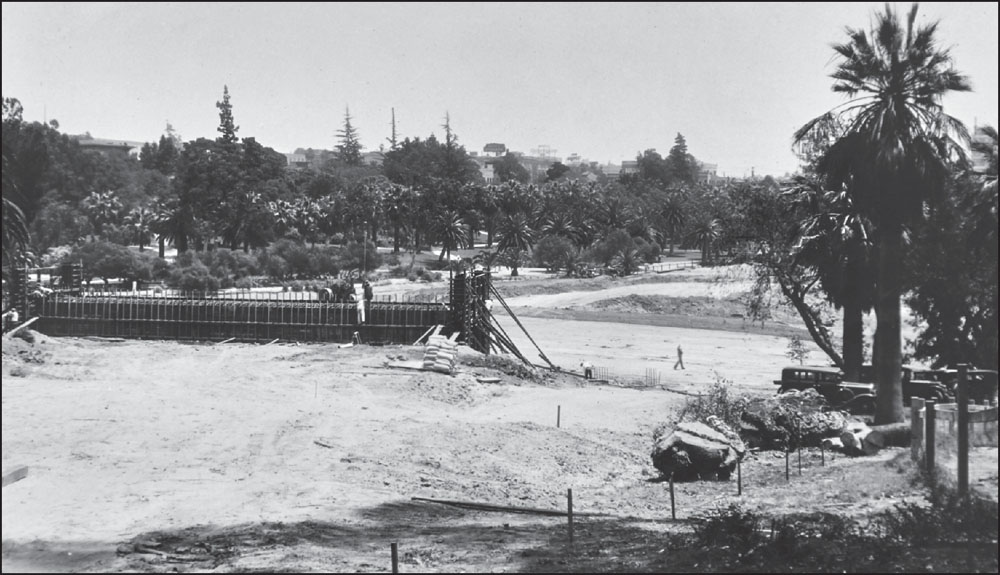

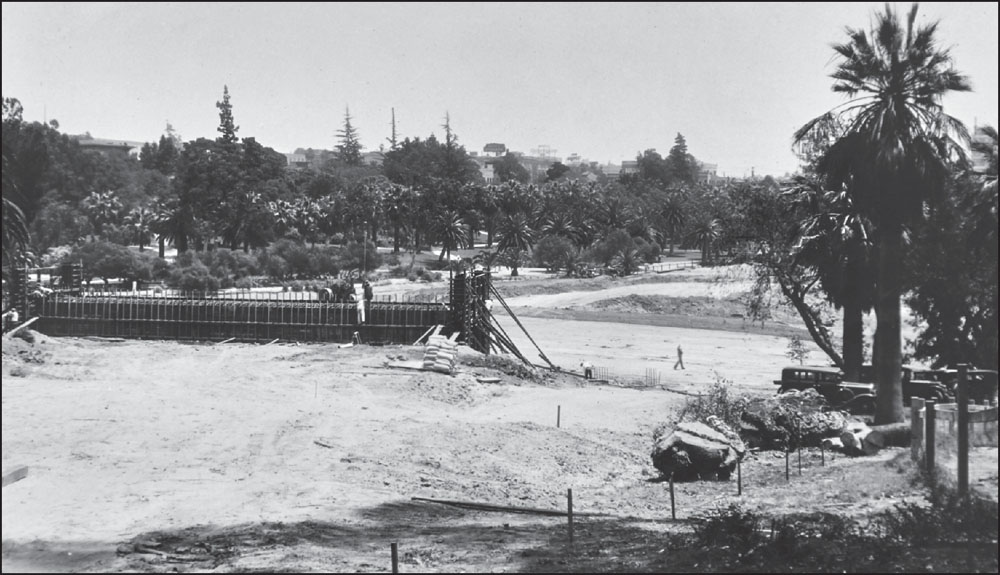

Although local community leaders were able to delay the beginning of construction by citing the original 1886 ordinance’s noncommercial clause, the city council ultimately approved the low-cost alternative. With the lake drained and the mature trees felled, this view looking east from Park View Avenue clearly demonstrates the monumental change underway in the “greatest park in the center of the city” that the resolution (June 1931) from the Wilshire Community Council, in opposition to the project, predicted. (Courtesy of the Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection.)

As digging ensued for the viaduct in 1933, one must not forget that the aftershock of the stock market crash and the subsequent Great Depression continued to reverberate across the desperate city. Indeed, a portion of the funding came from the federal government to stimulate job creation and growth. Interestingly, in the heat of the approval battle, a local labor union, the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers, submitted a letter stating that the city “refrain from taking action relative to bisecting the park.” (Courtesy of Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection.)

With the lake drained, the park became a construction wasteland. The “heavy turmoil of a noisy city” that local stakeholders were trying to prevent from infringing upon the park had arrived, with bulldozers, scoopers, and cranes. Concrete forms were replacing the nearly 50-year-old trees and shrubbery. (Courtesy of the Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection.)

In this view looking northeast toward Alvarado Street, the first concrete foundation for Wilshire Boulevard emerges from the wet ground like a prehistoric gray whale cresting in the turbulent Pacific Ocean, heading south towards warmer waters. For commuters and business people traveling on the soon-to-be-finished Wilshire Viaduct, their journey to the cold, blue ocean would take them in a westward direction, with traffic creating the turbulence. (Courtesy of the City of Los Angeles Archives.)

This view looks northwest toward the same concrete foundation. The Park Plaza and Bryson Apartment House stand in the hazy distance, awaiting an undetermined future. City engineers and construction managers paid particular attention to mitigating the high water level of the basin, an issue that continues to impact current building proposals. (Courtesy of the City of Los Angeles Archives.)

Even Colonel Otis could not stop progress, especially with heavy construction under way directly behind the statues. The memorial, originally located across the street from his former estate, was relocated to its current site near the southeast corner of Park View Street and Wilshire Boulevard. But, the colonel did not miss a beat, he continues to point in the direction of his abode from his current resting place. (Courtesy of the City of Los Angeles Archives.)

The concrete forms for the south pedestrian tunnel are well under way. The twin tunnels under the viaduct would provide critical links between the north and south side of the park. With the tunnels, pedestrians would not need to cross busy Wilshire Boulevard to enjoy either side of Westlake Park. A glimpse of the Westlake Theatre is in the upper right of the photograph. (Courtesy of the City of Los Angeles Archives.)

One of the tunnels nears completion. Over the decades, the tunnels became famous and infamous for their public art and criminal activity. Although each tunnel is relatively short in length, pedestrians have learned to walk quickly through the tunnels, partly out of safety concerns, but primarily because the park views on either side of the tunnels are indeed stunning. (Courtesy of the City of Los Angeles Archives.)

In this view looking westward, the Wilshire Viaduct has taken shape. Construction crews are laying down lane striping for the surge of vehicular traffic that would soon baptize the newest roadway of the optimistic city. Echoing amongst the surviving trees of the park were the cautionary words of the Wilshire Community Council: “Diversion of traffic . . . through this park would endanger the health of the occupants of said park . . . in as much as the expelling carbon monoxide would settle to the trees.” (Courtesy of the Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection.)

The viaduct is complete, and the street ready to open. Certainly, supporters of the Wilshire Viaduct like the Wilshire Boulevard Association, the Central Business District Association, the Downtown Business Men’s Association, and, last but not least, the Los Angeles Traffic Association celebrated this momentous day for the city’s growth. Westlake Park was now a pass-through park instead of a destination park. (Courtesy of the Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection.)

A couple of decades after the completion of the viaduct, Westlake Park, now officially called MacArthur Park, hosted city officials and other dignitaries to kick off the construction of the Gen. Douglas MacArthur Memorial near the southeast corner of the park. Over the years, countless war and veteran–related commemorations have taken place at the MacArthur statue. Today, the memorial is showing signs of decay and needs a major restoration. (Courtesy of the Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection.)

By the late 1980s, transformative change was again visiting MacArthur Park by way of the Red Line Subway system. In this aerial, the lay-down zone for the construction of the subway station across from the park on Alvarado Street is beginning to take shape in the lower center of the photograph. Construction of the Red Line would take several years and, once completed, bring thousands of new visitors into the neighborhood, especially to enjoy those Langer’s pastrami sandwiches. (Courtesy of Metro.)

The construction trench extended several blocks eastward from the station site. In the distance is the Los Angeles skyline and the final destination for the Red Line subway. Fortunately, the alignment of the subway line did not result in the demolition of any historically significant structures. Many of these buildings have now undergone some level of restoration since the completion of the subway line. (Courtesy of Metro.)

The subway station platform begins to take form between Alvarado Street and Westlake Avenue. Incredibly, the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (Metro) originally contemplated bypassing the park for a station. Fortunately, attentive elected officials and aggressive community organizing led to a more enlightened system alignment that resulted in a MacArthur Park station. (Courtesy of Metro.)

This incredible aerial demonstrates the topographical impact on the park during the subway construction. The author’s nine-year-old son described it as “if Godzilla himself scratched the earth with his giant claws.” In a scene looking eerily like the construction of the Wilshire Viaduct several decades ago, builders created a long scar-like corridor to facilitate the placement of the earth grinders that would continue the underground digging of the dual subway tunnels. (Courtesy of Metro.)

The earth grinders, pictured here several feet below what would be the water surface of MacArthur Park, prepares to bore into the earth on their westward journey, not to the ocean like Wilshire Boulevard, but to Koreatown, Hollywood, and eventually North Hollywood, the new centers of growth and development in the new century. The historic viaduct street lighting is just to the left of the construction trailer. (Courtesy of Metro.)

After the construction tempest comes the calm of renewal for MacArthur Park. As the 1990s began, the park stood ready for its next phase of life, this time with a concrete-surfaced lake bottom. The removal of its natural bottom necessitated the installation of aeration systems to ensure healthy water quality. Unfortunately, the system proved to be inadequate in keeping the water clean. Many local observers comment that it may be time to bring back a more natural state to the lake. According to the Los Angeles Times, it cost about $31,000 to refill the lake in the late 1980s. (Courtesy of the Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection.)