Astronomy and Astrology

Historical Background

Unlike people of ancient times, we tend to stay in our own backyard of the solar system. This strikes me as odd for a civilization with space telescopes that allow us to see farther than our ancestors ever dreamed. In this book, we will explore the constellations, learn how to look for them, and discover new ways to bring star magic into our lives.

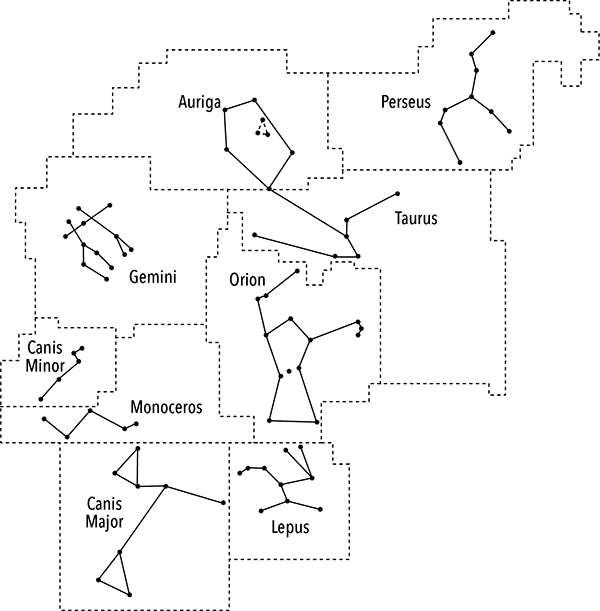

Modern astronomy recognizes eighty-eight constellations, some of which are based on the forty-eight ancient Greek star figures described by the mathematician Claudius Ptolemaeus (circa 100–170 CE), better known simply as Ptolemy. The other forty modern constellations are based on European star atlases from the fifteenth through seventeenth centuries. Although the Latin names of many constellations were derived from their earlier Greek designations, not all of them originated with Greek astronomers. While Ptolemy cataloged more than 1,000 stars, he associated them with constellations that had been known for centuries, many of which originated with Sumerian and Babylonian astronomers.

Ptolemy’s knowledge of astronomy is believed to have come indirectly from the Egyptians, Chaldeans, and Phoenicians. His information was more directly derived from the work of Greek mathematician Eudoxus of Cnidus (circa 390–340 BCE) to whom scholars have attributed the earliest text on the constellations. Eudoxus traveled widely to study a number of disciplines, including medicine and law. While his work itself does not survive, his star figures were known through the writings of Greek poet Aratus (circa 315–245 BCE). Aratus’s literary work entitled Phaenomena was often used as an introduction to astronomy and is the oldest description of the constellations that has come down through the centuries intact.

Other early stargazers and chroniclers were the Greek mathematician Eratosthenes (circa 276–194 BCE), who described forty-two constellations, and the astronomer Hipparchus (circa 170–127 BCE), who noted forty-eight groups of stars. It was Hipparchus who discovered the ongoing shifting of the stars that we know today as “precession,” or “precession of the equinoxes.” Regardless of source, the Greeks wrapped the star figures in their own mythology and created an ongoing drama in the night skies. Arab, Persian, Roman, and later medieval European astronomers also adopted this interpretation of the constellations.

While Greek influence on astronomy was widespread, the Greeks were not the earliest stargazers. The Babylonians, Persians, Egyptians, Indians, and Chinese also studied the heavens. As early as 2300 BCE the Chinese were coordinating their twelve zodiac signs with twenty-eight lunar mansions.3 The Hindus of India had a similar system by which they tracked the moon’s progress across the stars, and they associated a particular star with each lunar mansion. The Assyrians regarded the stars as divinities with either benevolent or malevolent powers.

In later times, as Europeans made contact with tribal people around the world, it was discovered that they also observed the stars and made it part of their lore. The Bushmen of Africa considered the stars to have been people or animals that once walked the earth. In New Zealand, the stars were regarded as legendary heroes whose brightness depended on their greatness in terrestrial battle before passing on to the heavens. As well as being regarded as the children of the sun and moon by the early people of Peru, the stars were believed to function as guardian deities. And last but not least, many Native American tribes looked on the constellations as celestial counterparts to powerful terrestrial animals.

Most early cultures observed the seasonal differences in the night sky as the star patterns changed over the course of a year. Providing a longer count than the moon, reckoning by the stars enabled people to mark time for planting, harvesting, and ritual. Visible year round, the circumpolar stars and especially the North Star—that reliable beacon that never moved—provided markers for navigation through the night seas. Building on what had gone before, the Greeks also used the constellations for navigation and agriculture. This is evident in the works of the writer Homer (eighth century BCE) who described Odysseus, the hero of his stories, navigating by the stars. Additionally, the poet and farmer Hesiod (circa 700 BCE) advised others on how to use the stars for determining the right time to plant their fields. The aesthetic beauty of the constellations also served as a decorative motif for the Greeks, who painted them on domed ceilings, and the Romans, who worked them into tapestries with threads of gold and silver.

Based on a set of tablets dating to approximately 1800 BCE, scholars believe that the Babylonians knew how to use calculations to fill in for the times when observations could not be made due to weather conditions or other circumstances. These tablets span one thousand years and are thought to be a type of calendar that includes listings of stars along with observation dates and times.4 Using this information and incorporating the divination results of their stargazing into their daily lives developed into a system that is considered to have been far more complex than our present-day astrology. Using the stars for in-depth horoscopes to guide daily life was not the only important aspect for some people in ancient Mesopotamia. During the first and second centuries, Sabianism, or star worship, sprang up in the city of Harran. This early Sabianism has been described as involving astrology, star worship, and magic. Although Sabianism was part of the pre-Islamic religion of the Harranians, the term Sabian was later applied to any form of star worship.

The Egyptian’s system of celestial observation dates to the Old Kingdom (circa 2650–2150 BCE); however, it was not as complex as the one used by their northern neighbors in Babylon. Even so, their star calendar contained thirty-six groups of stars. Within eight centuries from the initiation of their sky studies, the Egyptians were building temples and monuments that aligned with certain stars. In addition, they divided the night sky in half with Meskhet, the Big Dipper, as the northern marker and Sopdet, the star Sirius, as the southern marker. The constellation Orion was known as the Guardian of the Soul of Horus.

While the classical civilizations left records of their stargazing, little was known about any such endeavors by northern Europeans, where there were no great cities and no early forms of writing. Germany was generally considered the dark heart of Europe, primitive and uncivilized. However, the discovery of the Nebra sky disc in 2001 has changed that presumption. Found in central Germany, this bronze disc has a diameter of twelve and a half inches and it is embossed with gold leaf depictions of the crescent and full moons, the sun, and stars. It has been dated to 1600 BCE. After considerable study, scholars believe that Bronze Age Europeans were far more sophisticated than previously thought. According to astronomer Wolfhard Schlosser of the Ruhr University at Bochum, Germany, Bronze Age sky gazers knew as much as the Babylonians. In addition, their astronomical knowledge and abilities allowed them to use a combination of solar and lunar calendars.

With some surprise, scientists realized that the small group of seven stars on the Nebra sky disc actually depicts the Pleiades, a cluster of stars in the constellation Taurus. Realistic star images did not appear until 1400 BCE in Egypt, making the Nebra sky disc the oldest accurate picture of the night sky. In addition, the mysterious golden horizon bands that were originally thought to represent some sort of solar boat turn out to be markers for the solstices. Actually, this is not so startling because all across northern Europe many standing stones erected in prehistoric times were aligned to mark the solstices. According to Professor Miranda Green of the University of Wales, the Nebra sky disc presents a mosaic of symbols that were part of a complex European-wide belief system. I found it wonderful to learn that the early Pagans of Europe who erected stone circles and alignments to celebrate the solstices were also gazing beyond to the stars.

After the decline of the Roman Empire, Europe entered the chaotic period known as the Dark Ages (approximately 476–800 CE), when the advancement of learning and knowledge came to a virtual halt. Luckily the observations and ideas of many ancient stargazers were translated and kept alive by scholars in the Middle East. A great deal of this work was re-translated from Arabic to Latin during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries as it was carried back into Europe. However, during the Dark Ages, Ireland was a little bright spot in Europe that quietly maintained a high level of culture and learning.

Writing about early Irish astrology, distinguished Celtic scholar, historian, and author Peter Berresford Ellis noted that the Irish, and Celts in general, had a long tradition of astrological study. As the first-century-BCE Coligny Calendar demonstrates, Celtic cosmology was highly sophisticated. In addition, the ancient Brehon Laws of Ireland required that astronomers/astrologers prove their level of qualification in order to practice their art. Prior to Arabic texts on astronomy and astrology being translated into Irish in the twelfth century, the earliest writings in Ireland reveal a native concept when naming the constellations and planets. For example, the constellation Leo was called An Corran, “the reaping hook,” which describes the sickle shape of stars that define Leo’s head.5 Ellis also noted that the astronomical information on stars, comets, and other celestial bodies recorded in the various annals and chronicles of Ireland were more accurate than many others produced in Europe at that time.

With all the knowledge that had been accumulated in the ancient world, it was Ptolemy’s work that stood the test of time until the fifteenth century when scientific study took off. Polish mathematician and astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543) put forth his theory that the sun was the center of the universe and not Earth. Although his idea was controversial at the time, it marked the beginning of a change in the way people viewed Earth and its place among the stars. Danish nobleman and astronomy enthusiast Tycho Brahe (1546–1601) built an observatory and, without a telescope, accurately mapped almost eight hundred stars. In 1603, German astronomer Johann Bayer (1572–1625) published a star atlas that was the first to map the entire sky. Bayer also established the naming convention for stars within a constellation that is still used today. Another important astronomer of the time was Johannes Kepler (1571–1630), who put forth the laws of planetary motion.

While modern scientific study of the stars was getting started during this period, there was no distinction between astronomy and astrology as there is today. In fact, the great founders of modern astronomy were also astrologers. It is somewhat ironic that during the scientific revolution astrology remained an integral part of astronomy, mathematics, and medicine. In general practice, medieval astrology was divided between the two applications of divination and medicine. The famed English herbalist Nicholas Culpeper (1616–1654) also wrote several books on astrology and integrated his astrological knowledge with his herbal practice. From a medical standpoint, various parts of the body were believed to be under the influence of the constellations of the zodiac. Because of this, a physician did not diagnose a problem until he performed a series of complex astrological computations. The end result would determine whether or not particular cosmic influences would be advantageous for the patient. Eventually the scientific thinking that developed after the seventeenth century demanded observable physical explanations. While this moved astrology outside the realm of science, its influence and popularity has not waned.

As mentioned, the work of ancient stargazers was kept alive in the Middle East, and many of the traditional names of stars that we know today are a mix of Arabic, Greek, and Latin as well as mistranslations from one language to another. The star Rigel in the Orion constellation is one such case. Instead of the hunter Orion, Arab astronomers saw this constellation as a female figure they called al-Jauza and named the bright star that marked her left foot Rijl al-Jauza, “the foot of al-Jauza.” Over the centuries and through several translations, Rijl evolved into Rigel. The spelling varied as well, which is why we find the same word spelled rigil as in the star name Rigil Kentaurus, “the foot of the centaur.” Also, many of the star names beginning with “al” stem from the Arabic “al,” which is the equivalent of the word “the” in English.

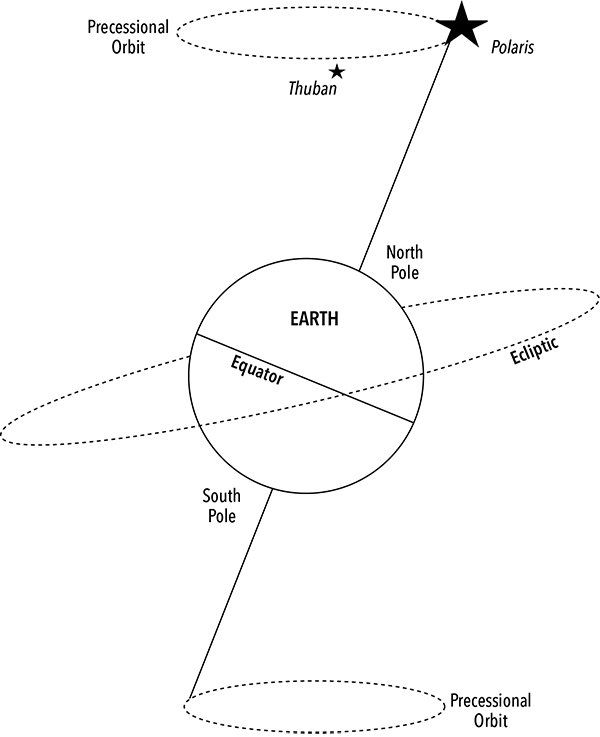

As we study the stars, we find that there are no older constellations in the far Southern Hemisphere. This is because that area of the sky was unknown to observers in the civilizations that discerned and named these star patterns. The classical constellations are centered on the north celestial pole as it was over 2,000 years ago. The north celestial pole is above Earth’s terrestrial North Pole, and, likewise, the south celestial pole is above the South Pole. Earth’s axis is tilted; it is not straight up and down. As a result, the terrestrial and celestial poles are at corresponding angles that shift over time due to Earth’s rotation and wobble. As our planet spins, it also wobbles like a top. The name for this wobble is “precession,” and it is caused by the gravitational pull of the moon and sun, which shifts Earth’s orientation in space.

If an imaginary line from the axis were extended outward into space, it would align with different stars over time. Because of precession, Polaris is now the nearest star to the North Pole and it marks the north celestial pole. Also known as the North Star and the Pole Star, Polaris is calculated to move closer to and within one degree of the North Pole around the year 2100. Also due to precession, approximately 4,500 years ago the star Thuban in Draco the Dragon constellation had that honor. While the Southern Hemisphere does not have a pole star, the nearest star to the south celestial pole is Beta Hydri in Hydrus the Southern Water Snake.

Precession is also known as “precession of the equinoxes” because Earth’s shift in space affects which constellation marks the spring equinox. This slow shift makes the sun appear to be lagging behind in its progression through the zodiac and over time the constellation that marks the spring equinox lags behind. The change in constellation at the spring equinox gave rise to the concept of “ages” or “astrological ages,” so when there is a constellation change at the spring equinox it is the beginning of that age. The Age of Aquarius is an example that most people have heard about. The full cycle of precession takes almost 26,000 years. Today the spring equinox occurs when Pisces marks the equinox, however; 2,500 years ago it was Aries. Earlier still, Taurus would have been the constellation at the equinox, which is thought to be one of the reasons that bulls have been associated with spring fertility rites.

Figure 1.1. Earth’s wobble causes the shift in pole stars.