What kept them going was the knowledge that everything on the earth has a purpose . . . and every person a mission.

—Mourning Dove, Native American author

Like most epic American stories, this one starts with the first American peoples—the Native Americans.

They invented the earliest forms of American commerce and entrepreneurship. And they had plenty of risks to manage and obstacles to overcome, like brutal weather, rough transportation, and huge distances to markets, just to name a few.

Before the Europeans landed on this continent, there were countless thousands of entrepreneurial men and women among the Native Americans, but due to the lack of written records we’ll never know most of their names. When the first French, Dutch, English, Spanish, Scandinavians, and other Europeans first touched shore on North America to seek fame and fortune, they stumbled onto a continent of vast, elaborate, and interconnected commercial trading networks among the native peoples, networks that had thrived for many centuries.

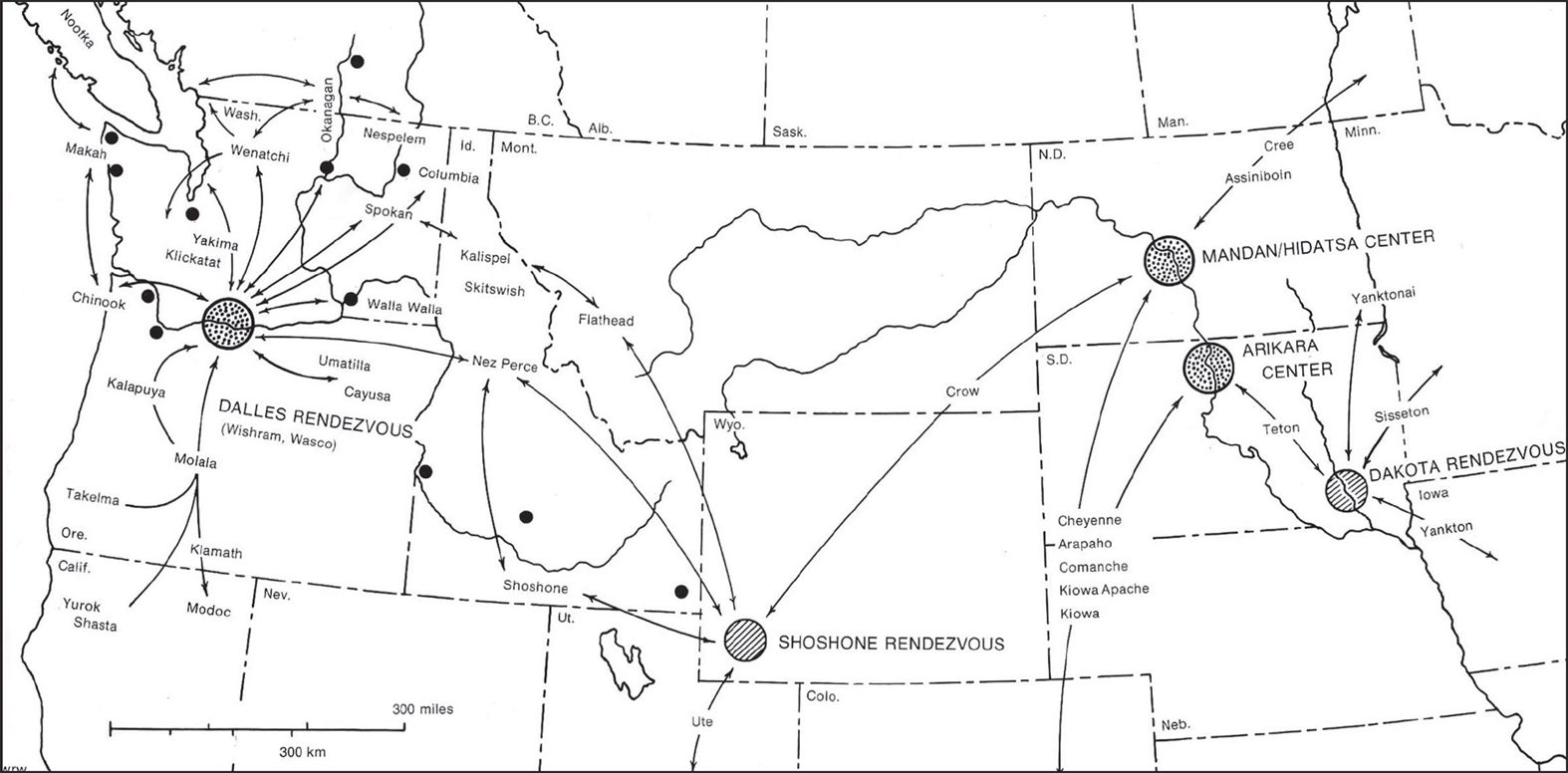

Some tribes were hunters, some were farmers, some fished, and some did all three, but many of them had one thing in common—they collected, traded, and sold goods to other tribes in trading patterns that linked many of the continent’s peoples together, in effect, into an international commercial network of suppliers, growers, artisans, traders, brokers, sellers, and repeat customers. From the Pacific and the Rocky Mountains to the Great Plains, Southwest, Canada, and the Atlantic coast, the Native Americans trafficked in flint, knives, arrowheads, animal products, vegetables, copper, marine shells, pottery, and countless other types of goods.

For many centuries, these trading patterns flourished across the northern and southern Plains and far beyond. Thirteen-thousand-year-old flint points cut from quarries in Texas have been discovered in eastern New Mexico, hundreds of miles away. Quarried stone from near Yellowstone in Wyoming made it all the way to the Ohio River Valley around the year 200 CE. Seashells from the Mojave tribe were traded for buffalo hides from tribes of the southern Plains, and the Hohokam tribe in present-day Arizona acted as the middlemen. Historians Emory Dean Keoke and Kay Marie Porterfield wrote that “by between 500 and 200 BCE, North American Indians had established a vital network of trade.”

The Native Americans were so entrepreneurial that they even put on their own trade fairs. The land that is present-day Wyoming, for example, was home to the Shoshone, a tribe that staged a regular regional trade fair called the “Shoshone Rendezvous.”

This was a big sales and trading event located in the river valleys of southwestern Wyoming west of the South Pass, and it served as a commercial link between the tribes of upper Missouri and those of the Rocky Mountains and Pacific Coast. “We think that the Shoshone were among the great Indian traders in the interior West,” said Dudley Gardner, professor emeritus of history and political science at Western Wyoming Community College. Crow Indians came to the rendezvous from the northern Plains; the Nez Perce, Shoshone, and Flatheads came from the Plateau and Great Basin; and Utes came from the Southwest. They all brought goods to trade.

Product testing in the field: Snake [Shoshone] Indians Testing Bows, by Alfred Jacob Miller. (The Walters Art Museum)

The Shoshone were especially famous for their hunting products, according to Maine-born trapper Osborne Russell, who worked in the Rocky Mountains fur trade in the 1830s, particularly “the manufacture of very powerful bows from the horn of a mountain sheep,” which were “beautifully wrought from Sheep, Buffaloe and Elk horns secured with Deer and Elk sinews and ornamented with porcupine quills and generally about 3 feet long.”

The business of Native America, you could say, was largely business in the form of trade and barter. Historian Samuel Western explained, “The Shoshone, it seems, traded with everyone, including northwest and southwest tribes. Other Rocky Mountain and central Plains tribes also took goods to the Missouri River valley to trade for corn, pumpkin, squash and native-grown tobacco. Their primary trading partners were the Mandan and Hidatsa of what is now North Dakota and, to a lesser degree, the Arikara, who were located north of the Grand River in present South Dakota. In his journal, William Clark of Corps of Discovery fame noted that the Arapaho conducted business with the Mandan, while the Cheyenne and Sioux traded with the Arikara.”

In the 1400s and 1500s, when Europeans started showing up on the eastern Atlantic horizon in fishing boats and bigger ships, few if any of them knew that the Norsemen had tried and failed before them—due to their small numbers and inability to establish friendly relations and trade links with the local native peoples—to settle in what is now Newfoundland around the year 1000. The new European visitors brought their own faiths and business ambitions with them, plus new technologies and products to sell and trade. Sometimes they brought disease, alcohol, overwhelming firepower, and sneaky business practices with them, too.

At first, the wary Native Americans held the Europeans off and literally kept them at arm’s length. Early-sixteenth-century Italian explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano wrote, “If we wanted to trade with them for some of their things, they would come to the seashore on some rocks where the breakers were most violent while we remained on the little boat, and they sent us what they wanted to give on a rope, continually shouting to us not to approach the land.” Eventually, of course, the Europeans landed, pushed far inland, set up trading posts, and made deals with the locals in exchange for guns and ammo, horses, clothes, cooking utensils, and lots of other goods.

A key part of this sophisticated trading network was the native middlemen, who linked their own trading centers together over vast distances. The Cheyenne were brokers between hunting tribes of the southern Plains and tribes in upper Missouri, and they shuttled European-sourced guns and horses to both. The Plains Crees carried manufactured goods to upper Missouri from Canadian fur traders and brought back corn and horses. In the southern Plains, the Apaches competed with the Comanche and the Jumano tribes for the profitable middleman business between the Pueblos and the Wichitas. Depending on the product and distance involved, markups could range from 100 percent to 300 percent or more.

The arrival of horses in large numbers meant Native American tribes could, for a time, hunt and trade much more effectively and expand their trading territory. “The high tide in typical Plains culture seems to have come in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries,” anthropologist Clark Wissler wrote in a 1914 essay. “This was the era of trade, yet the horse increased the economic prosperity and created individual wealth with certain degrees of luxury and leisure; also it traveled ever ahead of the white trade and white trader.” Horses provided Native American commerce with a quantum leap in mobility and the ability to carry trading goods far and wide.

Corn was an especially prized commodity. “For the Sioux, corn was more important than blood,” wrote James P. Ronda, professor of western American history at the University of Tulsa, and in August, “as in every other late summer and early fall, Sioux bands flocked to the Arikara towns, bringing meat, fat, and hides from the plains and European-manufactured goods from the Dakota Rendezvous.”

For the Europeans, America was often the target of grand moneymaking schemes and entrepreneurial ventures. Christopher Columbus came in search of new trade routes to Asia for tea and spices. The doomed early-seventeenth-century explorer Henry Hudson was on assignment for the Dutch East India Company to try to find the Northwest Passage, which everyone hoped would become a business superhighway, when he was set adrift in a small boat by his mutinous crew.

Native American trading centers and networks in about 1775, before the mass arrival of Europeans. (Courtesy Professor W. Raymond Wood)

While the Pilgrims journeyed to America mainly to escape religious persecution in England, it was an entrepreneurial venture, too—they planned to launch a fishing business in the New World to pay the bills. They were so inept at first that the Native Americans had to rescue them more than once. Eventually, though, the New England Puritans and their descendants became so good at fishing and shipping that they ushered in a two-century-long economic boom. No wonder there’s a big carved wooden sculpture of an Atlantic codfish hanging in a place of honor in the Massachusetts State House.

Many of the English American settlements and colonies, like Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, and Virginia, were set up by for-profit corporations and were expected to turn a profit. Founder William Penn saw Pennsylvania as a “Holy Experiment” for Quakers to thrive in peace and religious freedom, but he expected a return on his investment, too, declaring flatly, “I want some recompense for my troubles.”

Back then, outside of major security issues on the frontier with the increasingly resentful native tribes, America was a great place to start a business, with its seemingly unlimited resources and free market. America was not shackled by feudal systems, aristocrats, entrenched guilds, or dug-in monopolies and cronyism like much of Europe was for many centuries, so the settlers and colonists had an even playing field and unlimited prospects. At least in theory.

The for-profit Jamestown settlement, a venture launched in 1607 by the Virginia Company, was a joint-stock company, a new kind of investment vehicle meant to limit risk and liability for large groups of investors. Historian John Steele Gordon wrote, “By limiting liability, corporations greatly increased the number of people who could dare to become entrepreneurs by pooling their resources while avoiding the possibility of ruin. Thus the corporation was one of the great inventions of the Renaissance, along with printing, double entry bookkeeping, and the full-rigged ship.”

From this spot, a nation of entrepreneurs was symbolically born. New Amsterdam, later to become New York City, was the greatest incubator of commerce the world had ever seen. (T’Fort Nieuw Amsterdam op de Manhatans, 1651, New York Public Library)

But the Jamestown entrepreneur-settlers made nearly every mistake in the book—instead of planting crops, they prospected for gold, of which Virginia has none; they tried and failed to launch a glassmaking business; and so on. Many of them starved, and conflict erupted with the Native Americans. By 1618, the time the West Indian tobacco crop took off as a highly profitable business that made Virginia rich, it was too late for the Virginia Company, which had already, as many entrepreneurs do, gone broke.

Modern America got a big burst of entrepreneurial mojo from the energy and cash that flowed in and out of a spot today known as New York City. And the DNA of that city came from the Dutch.

New York was settled in 1624 as “New Amsterdam” by the Dutch West India Company, a national joint-stock company. It was a trading post, with beaver pelts the hot commodity. For the hyper-entrepreneurial Dutch settlers and merchants, profit was the name of the game.

Fur was like gold to a seventeenth-century merchant. As living standards in Europe rose, fur products like hats, coats, collars, muffs, and capes became fashion essentials. Beaver hair was considered the filet mignon of fur, thanks to a unique product feature: beneath the glossy outer layer was another layer of thick, luxuriant short hairs that were turned into felt for warm, superpremium hats. Overall, the business was a good deal for both sides—the Dutch swapped items that the natives wanted, like kettles, axes, needles, and wool, for the precious fur. Tens of thousands of the lucrative pelts were shipped across the Atlantic to European markets.

The Dutch in New Amsterdam didn’t even bother building a chapel or a church for seventeen years—if you wanted to worship, you found a spot inside the big fort. Everyone was too busy making deals. And carousing—at one point, the making and drinking of alcohol accounted for fully one-quarter of the city’s real estate.

“The Dutch founded New Amsterdam for the sole purpose of making a buck,” wrote historian John Steele Gordon. “And the Dutch in this period were very, very good at doing so. The Netherlands was rapidly becoming the wealthiest country in Europe at this point, and it had the most-developed banks, stock market and insurance companies.” This new Dutch trading outpost on the edge of the wilderness was a hardworking, hard-partying city. In 1647, incoming governor Peter Stuyvesant described it as “more a mole-hill than a fortress,” whose inhabitants had “grown very wild and loose in their morals.”

The city of New Amsterdam was a freewheeling hodgepodge of languages and ethnicities—in the 1640s, a French priest reported that at least eighteen languages were being spoken by the town’s fewer than one thousand people. By then the city’s entrepreneurs were already trading with customers in Europe, Africa, and the Caribbean. The city “didn’t care what people there thought about God,” according to writer John Sullivan. “It cared about beavers. It cared very, very passionately about beavers. If you didn’t get in the way of the beaver-pelt trade with Europe, you were an honorary New Netherlander.”

By 1664 the island was a high-profit entrepreneurial cash machine for the Dutch. By then, the city boasted residents from a number of European nationalities, African slaves, some free blacks, and religious minorities including Quakers, Anabaptists, and Jews. This diversity and tolerance may have been the “secret sauce” that nourished the phenomenal growth of New York, and America, ever since. Having a magnificent harbor helped a lot, too.

Suddenly, in the summer of 1664, the party came to an end. Four warships belonging to Great Britain, the Netherlands’ chief commercial rival, appeared in the harbor and demanded a surrender, their cannons pointed at the thriving settlement of nine thousand people. The Dutch governor Peter Stuyvesant, who commanded virtually no military force of his own, wisely gave up without any blood being spilled. The British moved in and renamed the area New York, but left much of its freewheeling, deal-making character in place.

Over the next three centuries, the little island, blessed with the entrepreneurial spirit of its long-forgotten Dutch founders, mixed an astonishing diversity of human capital packed into one of the prime business locations on the planet—and became the greatest commercial incubator the world had ever seen. “If what made America great was its ingenious openness to different cultures,” wrote author Russell Shorto, “the small triangle of land at the southern tip of Manhattan Island is the birthplace of that idea: This island city would become the first multiethnic, upwardly mobile society on America’s shores, a prototype of the kind of society that would be duplicated throughout the country and around the world.” By 1774, reported visitor John Adams, the New Yorker’s rapid-fire style of street talk had already appeared: “They talk loud, very fast, and all together. If they ask you a Question, before you can utter 3 Words of your Answer, they will break out upon you, again—and talk away.”

In 1818, New York started the first regularly scheduled shipping service to Europe, which triggered a boom in transatlantic commerce. Seven years later, the Erie Canal connected the port city with the flourishing American Midwest. In 1825, Governor DeWitt Clinton envisioned that New York would become “the emporium of commerce, the seat of manufacture, the focus of great moneyed operations and the concentrating point of vast, disposable and accumulating capital.”

How right he was. Entrepreneurs and investors launched banks and insurance companies. New York became the capital of meatpacking, textiles, finance, fashion, advertising, communications, and the media—and speed-talking! It was, in the words of Oliver Wendell Holmes, the poet and father of a Supreme Court justice, the “tongue that is licking up the cream of commerce and finance of a continent.”

New York never forgot its earliest moneymaking roots in the fur trade. Today the city’s official seal features two trading partners—a Native American and a Dutch settler—and a friendly beaver.

Before long, the thriving American colonists got fed up with British interference in their business, mainly in the form of increasingly excessive taxes, and they decided to give them the boot. The American merchants, shopkeepers, artisans, farmers, hunters, and workers were, overall, making tons of money, and naturally they wanted to hold on to their fair share. “By the time the 13 colonies declared independence, they were, after only 169 years, the richest place on earth per capita,” wrote historian John Steele Gordon. As he put it, “No wonder the British fought so hard to suppress the rebellion.” The Americans were so prosperous and well fed that on average the Continental Army troops were fully two inches taller than the British enemy troops they fought against.

The art of the deal, Manhattan-style: Peter Stuyvesant, governor of New Amsterdam, negotiates a deal with Native Americans, 1660. The Dutch merchants, traders, and entrepreneurs were so busy wheeling and dealing that they didn’t build a church for seventeen years. (Getty Images/Alamy)

It was time for America’s greatest early entrepreneur to take the stage, and take charge.

He was a tall, powerfully built war veteran, farmer, horseman, slave owner, and experienced frontiersman who hailed from the state of Virginia, where he launched one of America’s first and biggest diversified agrobusinesses.

He was the original “buy American-made” man, too. When he was sworn in as president on April 30, 1789, he wanted to encourage American entrepreneurship in a time when imported British goods dominated the fashion market—so he insisted on wearing a plain brown suit made with cloth woven in Hartford, Connecticut.

He went by the name of George Washington.