Building the national prosperity is my first and my only aim.

—George Washington

On August 11, 1781, the two greatest entrepreneurs in America held the fate of the nation in their hands.

General George Washington was commander in chief of the Continental Army, and Robert Morris, who was acting as his de facto chief financial officer, was a Philadelphia-based import-export mogul who was believed to be the richest man in the American colonies.

The two men faced a crisis that is common to the founders of many start-up ventures—they were burning through their operating cash faster than they could raise new funds. They couldn’t meet their payroll of nearly ten thousand employees (soldiers), and they couldn’t feed or supply them, either.

They held an emergency summit meeting at Washington’s military camp on the banks of the Hudson River at Dobbs Ferry, New York. Morris raced there from Philadelphia on a fast horse.

As usual, former agribusinessman Washington was terribly worried. He was in his seventh year of commanding the American Continental Army, a motley collection of troops with mismatched uniforms and weapons who tended to lose many more battles than they won, sometimes went without shoes, food, and pay, and occasionally threatened to stage a mass desertion or even mutiny. They’d fought, escaped, harassed, and worn down the British Army to a stalemate, and now Washington prepared to deliver a death blow to the enemy army’s main force, at that point comfortably ensconced in New York City, just two dozen miles to the south.

But as usual, Washington was running out of cash.

To fight a war, you’ve got to have money, and lots of it, and Washington noted that “in modern wars the longest purse may chiefly determine the event.” But as soon as money arrived for the army, it went out, and Washington and his men constantly had to beg, borrow, and scrounge from state governors, merchants, and legislatures to stay afloat as a fighting force. Time and time again, financial crises threatened to collapse the Continental Army, and the dream of American freedom. At this point in the summer of 1781, Washington had thousands of allied French troops camped nearby ready to fight alongside the Americans, but by now the French war chest in North America was nearly empty, too.

“We are at the end of our tether,” Washington wrote that April, and “now or never our deliverance must come.”

Before he went to war against the British, George Washington was, like Robert Morris and many of their fellow revolutionaries, an entrepreneur. As one writer put it, in 1776 small business was the “backbone of the nation, and the vanguard of the revolution was shopkeepers, merchants, farmers, and small exporter-importers who were tapped into the growing North American trade with the Caribbean and Europe.” America was “the first country in the world in which business people got involved in the political system,” observed Edwin Perkins, history professor at the University of Southern California.

The American Revolution was, in large part, a rebellion of entrepreneurs, many of them concentrated in fast-growing commercial centers like Newport, Rhode Island; Boston; New York City; Philadelphia; and Charleston, South Carolina; and satellite port cities like Norfolk, Virginia; New London, Connecticut; Savannah, Georgia; and Wilmington, Delaware. “From the earliest American settlements, colonial commerce was the province of diverse groups of settlers,” wrote historian Carl E. Prince. “Puritans in Boston, Pilgrims at Plymouth Plantation, Quakers in Philadelphia, Dutch in New Amsterdam (New York City), and Scots in the Chesapeake were all part of the colonial American merchant establishment.”

Some of the earliest American small businesses often had simple survival as their goal, and were based on barter and community cooperation and trading exchanges between households, while others were more geared to profit and return on investment. Journalists Christopher Conte and Albert Karr wrote: “By the 18th century, regional patterns of development had become clear: the New England colonies relied on ship-building and sailing to generate wealth; plantations (many using slave labor) in Maryland, Virginia, and the Carolinas grew tobacco, rice, and indigo; and the middle colonies of New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware shipped general crops and furs. Except for slaves, standards of living were generally high—higher, in fact, than in England itself. Because English investors had withdrawn, the field was open to entrepreneurs among the colonists.”

Tragically, much of the colonial economy and its prosperity were powered by the shipment of New World goods like rum, molasses, and sugar to Africa, in exchange for kidnapped human slaves, who were packed on hellish ships and transported for sale in America in the gruesome process of the Middle Passage. Multitudes of innocent souls perished. In Africa, local entrepreneurs helped manage the mass kidnappings, and in America, local entrepreneurs cashed in on the selling of human flesh to end users. By the time the American Revolution erupted, there were nearly 700,000 slaves in the colonies.

Many of the fifty-six signers of the Declaration of Independence were self-made businessmen. Samuel Adams ran the family brewery business in Massachusetts before getting into politics. Philip Livingston from New York was a merchant, importer, philanthropist, and founder of the New York Chamber of Commerce. John Hancock, president of the Continental Congress, made one of the biggest fortunes in the colonies through his family’s merchant-shipping business in Massachusetts. Another Founding Father, George Taylor, ran a successful ironworks in Pennsylvania, and another one, Roger Sherman, started off as a shoemaker and shopkeeper.

Benjamin Franklin was a printer, publisher, and early American media mogul who franchised his printing shops all the way from New England to the Caribbean, and championed the American postal service so he and other entrepreneurs could have a distribution system. He was so successful in making money that he was able to retire at age forty-two, exactly halfway through his life, and devote the rest of his years to diplomacy and politics.

Among Franklin’s many business insights were: “Remember that time is money,” “Credit is money,” and the way to wealth “depends chiefly on two words, industry and frugality.” Franklin was a highly creative, disciplined business manager who “was not only one of the first, great entrepreneurs in colonial America, but in many respects he was the archetype of every American manager that followed him,” in the words of historian Blaine McCormick.

And then there was colonial businessman George Washington. He was, according to military historian Edward Lengel, “a crafty and diligent entrepreneur,” and his executive skills as a military leader and president were forged in his earlier career in business. He grew up in a single-parent household, did not receive a formal education, and turned a modest family inheritance into what was one of the greatest estates in America at the time he died. “He began early, employing principles imbibed from his parents, family, and friends to build his fortune,” Lengel noted. “His first income came from the salary he earned as a surveyor. Saving and investing, he used this to purchase land and grow tobacco. A modest inheritance helped to establish him as a substantial landowner and gifted him with an estate—Mount Vernon—that became his country seat. Marrying Martha Dandridge Custis, a wealthy widow who would become his devoted partner, George acquired the wherewithal to begin operations on an exalted scale.”

Washington started off learning the real estate business at age sixteen as an apprentice land surveyor. When he inherited the Mount Vernon plantation, the estate was two thousand acres, and through deal-making and real estate speculation, Washington expanded it to eight thousand acres at the time of his death. Over the years, Washington expanded his business operations into a full-scale industrial village. According to historian Harlow Giles Unger, Washington grew “a relatively small tobacco plantation into a diversified agro-industrial enterprise that stretched over thousands of acres and included, among other for-profit ventures, a fishery, meat processing facility, textile and weaving manufactory, distillery, gristmill, smithy [blacksmith shop], brickmaking kiln, cargo-carrying schooner, and, of course, endless fields of grain.” In 1785, with the backing of the Virginia and Maryland legislatures, Washington launched America’s first trade development company, the Potomac Company, a partnership of private and public capital that built canals along the river. Like many land-rich plantation owners, however, Washington had liquidity problems and was often cash-poor.

George Washington’s estate at Mount Vernon. (New York Public Library)

As an entrepreneur, Washington was a hard-core micromanager. He was in constant motion around his estate, checking in on every little detail of his diversified operation, huddling up with his overseers and field managers, rolling up his sleeves to dig soil or tinker with a new piece of equipment. He demanded a constant flow of precise reports and information—numbers, prices, temperatures, measurements, and quantities. Writing in 1965, historian James Thomas Flexner described the hustle and bustle of Washington’s life as an entrepreneur: He “was up before dawn, forever on horseback supervising the plantation. In addition to growing tobacco, he had to make the whole operation as far as possible self-sustaining. Pork had to be produced by the thousands of pounds (6,632 in 1762), Indian corn raised to feed the Negroes, fish extracted from the Potomac to be eaten fresh by all and salted down in barrels for the hands. Fruit trees were grafted, cider bottled. Liquor supplied slaves with some incentive; after buying as much as 56 gallons at a time, Washington established his own still, which could in a day change 144 gallons of cider into 30 of applejack. An old mill—which Washington always referred to as ‘she’—had to be supplied with water to turn the wheels, fed with grain, and propped up, as she was very shaky in storms. His own carpenters erected the farm buildings and kept them in repair; his blacksmith was so busy he needed helpers. The mill and the artisans also worked for neighbors. Washington sometimes acted as retailer for his tenants, exchanging goods he had imported from England for tobacco.”

To improve efficiency, cut labor, and boost productivity, Washington experimented with new crops and rotation schemes, plows, pumps, seeds, livestock breeding, fertilizers, and tools. He was a technology buff, and scoured the newspapers for the latest gadgets and innovations from overseas. He gave his employees lots of pep talks, sharing nuggets of wisdom like, “Nothing should be bought that can be made,” “A penny saved, is a penny got,” “The man who does not estimate time as money will forever miscalculate,” and “System in all things is the soul of business.”

One of Washington’s key early decisions as an entrepreneur was to cut his losses and switch his product line by stopping the harvest of Mount Vernon’s heavily taxed and soil-damaging tobacco crop and switching to wheat. “By 1766,” wrote Mount Vernon director of restoration Dennis J. Pogue, “the disappointingly low prices that he was receiving in return for his tobacco harvest convinced Washington that he would be better off devoting the labor of his workers to producing other commodities that had a more dependable payoff.” Washington manufactured his own branded grocery store product—packaged flour, featuring his name right on the label as a sign of quality. The Mount Vernon flour mill was an advanced, three-story operation that manufactured some 275,000 pounds of flour per year, which were sold throughout the thirteen colonies and exported to Europe, too.

Every spring, during the six-week fishing season, Washington operated a profitable commercial fishing operation on the Potomac River, which ran right past his property. He once explained to a friend that the river was “well supplied with various kinds of fish at all seasons of the year; and in the Spring with the greatest profusion of Shad, Herring, bass, Carp, Perch, Sturgeon.” He added, “Several valuable fisheries appertain to the estate; the whole shore in short is one entire fishery.” Washington dispatched teams of slaves with rowboats and big nets into the river and they worked round the clock harvesting up to 1.5 million fish, including herring and shad, which were salted and packed in barrels. The unwanted fish scraps were used as fertilizer for his wheat crop. With Mount Vernon as his business and social headquarters, Washington rose steadily in Virginia and national politics until taking charge of the colonial military rebellion in 1775.

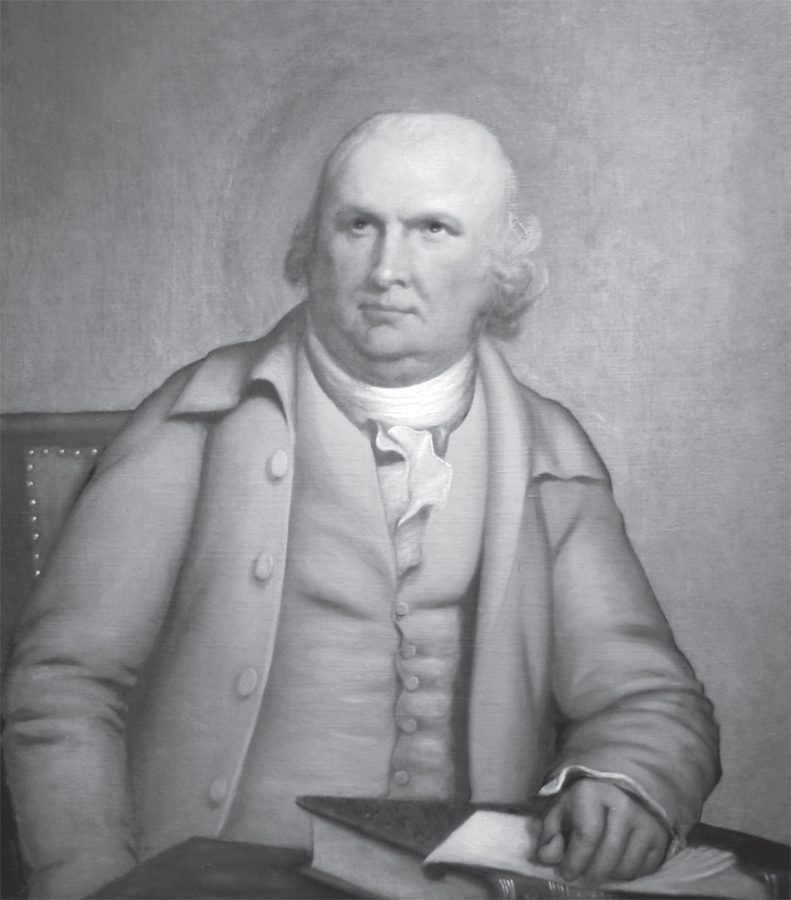

The man Washington was to meet with on August 11, 1781, Robert Morris, was born in England, and in 1747, at age thirteen, he moved to Philadelphia, where he went to work in the office of Willing, Morris & Company, an import-export company that became one of the top three wealthiest commercial firms in the American colonies.

By age twenty-three, Morris was showing such promise as a commodities trader that he was made a junior partner, and soon he was a fast-rising star in local politics and social affairs. Eventually he rose to become full owner of the company. At his office on the Philadelphia waterfront, in the days before a commercial banking system, Morris juggled loans, bills of exchange, lines of credit, and shipping schedules in a dizzying symphony of international finance. He did business with buyers and sellers in India, the Caribbean, the Middle East, Spain, and Italy, making him a true global capitalist.

The sheer head-scratching complexity of how Morris conducted business was explained by writer John Dos Passos in this way: “Since American merchants had to deal with the fluctuating paper currencies of thirteen separate provinces, transactions were basically by barter. Morris would trade so many hogsheads of tobacco estimated in Maryland paper currency, say, for a shipload of molasses in St. Kitts estimated in pounds sterling. In default of other currency, bills of lading would have to pass as a medium of exchange, so that half the time he would be using the bill of lading for the shipload of molasses to meet an obligation for a shipment of straw hats held by a merchant in Leghorn. Bills of exchange circulated that could be met part in cash, part in commodities, part in credit. Due to the slowness in communications, years might go by before any particular transaction was completed and liquidated. Add to that the hazards of wartime captures and confiscations, and the custom, so as not to have all their eggs in one basket, of a number of shippers sharing in a shipload of goods.” Are you confused yet? Morris explained to a friend a simple truth: “The commonest things become intricate where money has anything to do with them.”

Early American mega-entrepreneur Robert Morris, largely forgotten today, was a financial wizard who bailed out the revolution with his own cash and credit at least three times. Of all the revolutionary leaders, George Washington liked him the most. He had it all, including America’s biggest fortune—until the day it all blew up and he barricaded himself in his house with a shotgun. (Painting by Robert Edge Pine; photograph by cliff1066/Flickr)

With the dangers of piracy, shipwrecks, and long-delayed payments, it was a high-stakes, high-risk way to do business, and as Morris’s biographer Charles Rappleye explained, “He spread his stock among various business partners, and in ships plying the sea, so that any given moment might find him flush or strapped, calling in debts or laying large sums out in new ventures. Morris was rich in resources, but rarely in cash.” His financial juggling and manipulations were so complex that even he may have sometimes had trouble keeping track of it all. According to one account, “He carried the art of kiting checks and bills of exchange to a high degree of perfection. The fact that sailing ships took so long to cross the Atlantic made it possible to meet an obligation in Philadelphia with a note drawn on some Dutch banker in Amsterdam. That would give him three months to find negotiable paper with which he could appease the Dutchman when he threatened to protest the note.”

Before the war started, the gregarious Morris savored his life as one of America’s first super-rich citizens. He married a beautiful woman from a respected Maryland family and threw lavish parties at both his town house on Philadelphia’s Front Street and his country house across the Schuylkill River, where he kept an impressive fruit-and-vegetable garden and greenhouse. He explained to a friend that “mixing business and pleasure” makes them “useful to each other.” According to biographer Rappleye, Morris had a personality as striking as his business success: “He was tall. He was wide. Philadelphia was a great place for feasting and he was often the guy throwing the banquet. He was at home with stevedores as much as he was with fellow merchants and traders.” In the springtime, Morris served the finest fresh asparagus and strawberries; in summer it was apricots and plums; and autumn was the season for pears and hothouse grapes. He employed a French chef who served with porcelain settings and silver tableware, and guests knew that the claret and Madeira and roast meats served at Morris’s shindigs were of the finest quality.

Like many Americans, Morris grew increasingly angry at British actions that hurt colonial business, and the revolution that he was to help mastermind was itself largely based on a nasty, ongoing business dispute.

Americans wanted unrestricted free enterprise, and the simple ability to make money and keep it, but starting in 1764, the British tightened the screws on American business. They aggressively enforced the old Navigation Acts, which had been around for a century but were largely ignored by the Americans. They imposed the Sugar Act, the Stamp Act, and the Townshend duties, all of which strangled American profits, and the Intolerable Acts of 1774, which based British troops in American port cities, dissolved the troublesome Lower House of the Massachusetts legislature, and shut down the port of Boston. It’s little wonder that the First Continental Congress of 1774–75 launched a full-scale boycott of British imports, and before you knew it, the ultimate business dispute broke out—bullets were flying.

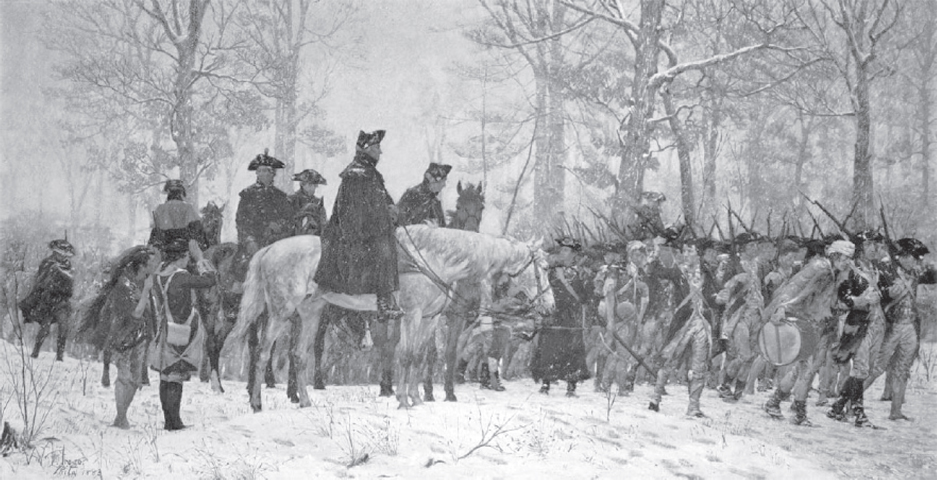

George Washington’s executive skills as a military commander and president were sharpened by his first career—as an entrepreneur. (Washington’s Retreat at Long Island, engraved by J. C. Armytage after an illustration by Michael Wageman)

Afraid of the impact that a break with Great Britain would have on business, and doubtful of the Americans’ chances of beating the British Army, Morris, now a member of the Continental Congress, signed the Declaration of Independence only reluctantly, but once the war was on, he was totally on board with the rebel cause. He orchestrated the smuggling of gunpowder from Europe and the Caribbean to the Continental Army, and used his wide international business contacts as a spy network to collect intelligence on British military moves. Morris coordinated a secret arms trade with Europe to supply the American army. He financed a fleet of privateers, ships that ran the British blockades to deliver aid to the colonies.

Morris came to the Dobbs Ferry summit meeting armed with one of the most powerful weapons of war—a balance sheet.

Once again, his good friend Washington was running out of cash, and without cash the revolution was doomed, along with his hopes for a free America. Washington was afraid that large sections of his troops were about to pack up and peel off if they weren’t paid, and fast. That was Robert Morris’s job.

Unlike the towering, stately Washington, who looked like a Roman god-hero chiseled in stone onto horseback, Robert Morris was a plump, gregarious, ultra-high-energy waterfront merchant and wheeler-dealer who hustled his way into one of the largest fortunes in colonial America through complicated financial improvisation and personal charm. Starting earlier in 1781, Morris almost single-handedly ran Washington’s army budget, and the entire financial system of the embryonic American revolutionary government, out of his own pockets and his own brain, with a blizzard of deals, notes, bills, and shipping documents that flew around his Philadelphia office. Historian Terry Bouton called Morris “the most powerful man in America—aside, perhaps, from George Washington,” and noted that “the degree of authority he possessed over the economy was probably never matched in the subsequent history of the United States.”

Earlier in 1781, the Continental currency had collapsed, the victim of hyperinflation and frantic government overprinting of money. A mock parade was held in Philadelphia by people wearing hats made with now-worthless paper bills. A sad-looking dog marched alongside them, with money pasted all over him. The Continental Congress turned the whole mess over to Robert Morris by appointing him “Superintendent of Finance” of the revolutionary government, a forerunner to the modern job of secretary of the Treasury. To accept the job, the hard-bargaining Morris demanded three conditions: he could hire anyone, he could fire anyone, and he could keep his private business going on the side. The desperate Congress accepted.

Washington and his freezing, starving troops at Valley Forge await deliverance, or death, in the winter of 1777–78. Twenty-five miles away, entrepreneur Robert Morris was frantically gathering supplies and cash for the Americans before they deserted—or died. (The March to Valley Forge, by William Trego, 1883, Museum of the American Revolution)

As soon as he got the job, Morris moved fast to cut waste, tighten accounting, and institute sealed competitive bidding for government contracts. But conditions looked hopeless, and soon Morris was exchanging messages of despair with General Washington, who was desperate for hard currency to pay his troops. He wrote to Morris: “I must entreat you, if possible, to procure one month’s pay in specie for the detachment under my command. Part of the troops have not been paid anything for a long time past and have upon several occasions shown marks of great discontent,” an understated reference to the possibility of mutinies by various Continental troops.

With the revolution under way, Robert Morris proved himself to be a flat-out financial wizard and management genius who stepped in to assist the rebels whenever he could, sometimes digging into his own pocket while at the same time keeping his own businesses running. In the winter of 1776–77, things got so bad that the Continental Congress, fearing capture by invading British forces, evacuated Philadelphia and fled to Baltimore, leaving Morris behind. He volunteered to run the revolutionary government almost single-handedly as de facto “chief operating officer” for three months.

General Washington and his troops camped out in the frigid woods of Valley Forge, some twenty miles from Philadelphia, and began freezing and starving to death. Morris scrambled around the chaotic docks of Philadelphia, untangled incoming shipments of weapons, food, and clothes, and organized wagon teams to express-deliver the cargo to George Washington and his troops just in time to stage their historic crossing of the Delaware on Christmas Day 1776.

By the end of December 26, Washington had pulled off his first big battle win, a knockout victory over Hessian mercenaries at Trenton that gave the American troops and colonists a critical boost of confidence. A week later, when the Continental troops were stuck on the west bank of the Delaware without food and on the verge of mass desertion, Morris again rushed food, supplies, and payments to them in the nick of time. He helped supply the colonial troops who triumphed at the Battle of Saratoga in 1777, and supported Washington’s troops during another savage winter, this time in Morristown, New Jersey, in 1779–80.

Even before Morris was confirmed as superintendent of finance in early 1781, wrote John Dos Passos, “he was beset by Continental officers with pathetic stories of want asking for advances. Sea captains poured out tales of capture and pillage on the high seas. Butchers, bakers, clothiers, drovers, crowded round his desk trying to turn their dog-eared bills into cash.”

By now, in the summer of 1781, George Washington and Robert Morris were proving to be a scrappy and highly effective management team. They shared a personal passion for American freedom, and for free-market capitalism unencumbered by high taxes and red tape. Both men had run thriving, sprawling international businesses before the revolution, and so far, they’d kept the American Revolution alive, just barely. But once again, the rebels had blown through nearly the last of their cash, and keeping the food and supplies flowing into the rebel battle camps was, as always, a logistical nightmare.

As he galloped toward the Dobbs Ferry emergency summit meeting, Robert Morris had a partial solution in his mind—George Washington had to cut costs. As the man in charge of Washington’s money, and like any responsible chief financial officer, Morris was going to tell the great man he had to streamline the army and somehow stop hemorrhaging red ink.

When the meeting got under way, Washington told his financier he couldn’t cut costs. In fact, he needed a new pile of money, and he was going to risk it all in one final major offensive, a desperate gamble to win the revolution and the war. He was going to directly attack the powerful British forces dug into the island of Manhattan in New York City.

The British had two main forces in America, one camped out in nearby New York City led by General Henry Clinton, and a second force under the command of General Lord Cornwallis that was wreaking havoc in the American South, laying siege to Charleston, capturing Savannah, and wiping out much of the American forces in the Carolinas. The good news was that a French expeditionary force of 5,500 troops was arriving in Newport, Rhode Island, and the French fleet was coming within range of the mid-Atlantic to do battle with the British Navy, but there was no guarantee of when or where this would happen, or if it would turn the tide. Meantime, the war could be won if Washington’s force of American and allied French land troops could overrun the British on Manhattan—and only if they were paid, fed, and armed.

Escorted by a force of twenty elite mounted troops, his mind no doubt racing with a whirlwind of ideas and fears, Robert Morris raced back toward Philadelphia on a fast-but-dangerous route that took him close to enemy lines. He had to pull together a financial rescue package for Washington and the troops to be able to strike at New York.

But days after the meeting, on August 14, Washington got word that the French fleet would be in position at Chesapeake Bay, Virginia, within just a few weeks, complete with “between 25 & 29 Sail of the line & 3200 land Troops.”

Time for a fast, and seemingly impossible, change of plans. Washington now planned an epic “feint” to fake out the British—and knock them out of the war. He would attack at Virginia, not New York.

Washington’s plan was to leave a token force outside of New York City, build big army camps and smoking brick bread ovens to make it look like they were digging in for a long stay, spread false intelligence to support the deception, and sneak more than four thousand French and American troops off on an epic march all the way from New York to Virginia. Instead of a fifteen-mile road march to British battle lines north of Manhattan, they would move 550 very long, expensive, hot, and humid miles all the way down to the Virginia coast. Once there, they would surprise-attack Lord Cornwallis’s troops at Yorktown and try to seal them off, where their escape would, hopefully, be blocked by the French warships.

If a presumably stunned Robert Morris choked on his tea while learning of this scheme, you couldn’t blame him. It seemed impossible. At first, Morris appeared totally flummoxed. On August 21, Morris stalled on Washington’s request for a cost estimate for the operation, saying he needed time “to consider, to calculate.” The next day, after checking the ledger books, Morris replied to Washington, “I am sorry to inform you that I find Money Matters in as bad a Situation as possible.”

But there was no turning back. With or without funds, Washington was already pulling out of camp and the allied troops were hitting the road to Virginia. Robert Morris had to scramble and pull off a miracle. There was barely time to panic. This was the Super Bowl of financial crisis management.

It was at this moment in American history that Morris’s skills as an entrepreneur came to the rescue.

On August 22, 1781, Morris sent “begging” letters pleading for money to each one of the thirteen states: “We are on the Eve of the most Active Operations, and should they be in anywise retarded by the want of necessary Supplies, the most unhappy Consequences may follow. Those who may be justly chargeable with Neglect, will have to Answer for it to their Country, to their Allies, to the present generation, and to all Posterity.” As usual, this didn’t help much, since the feeble Articles of Confederation that then governed the revolutionary cause had no financial teeth in them, no enforcement mechanism to collect funds.

Working round the clock, Morris begged, borrowed, and promised for money. He lined up fleets of small vessels to get the troops across the Delaware and Chesapeake rivers, and he arranged for six hundred barrels of provisions and loans from Spain and France to pay the troops.

He extended his own personal credit to support the supply effort, lined up more loans from the French government, arranged for supplies and funding through sources in Spain and Cuba, and even issued his own currency in $20 and $100 denominations, dubbed “Morris notes,” backed up by his own personal reputation and credit. Helping him was Philadelphia bond broker Haym Salomon, who was also notable as an early Jewish American hero of the revolution. It was a desperate race against the clock, and Morris sometimes seemed to come close to cracking under the strain. “It seems as if every Person connected in the Public Service,” he wrote in his daybook, “entertains an Opinion that I am full of Money for they are constantly applying even down to the common express Riders and give me infinite interruption so that it is hardly possible to attend to Business of more consequence.”

Fortified by the supplies and money orchestrated by Robert Morris and Haym Salomon, and led by General Washington, the American and French forces, now swelled to over ten thousand, arrived at Yorktown in late September. They soon laid siege to General Lord Cornwallis and his eight thousand troops, who were now pinned down by the French fleet offshore, who had blasted away a British Navy force near the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay in early September.

Back in Philadelphia, Robert Morris was at his financial wits’ end. He told a friend on September 20, 1781: “The late Movements of the Army have so entirely drained me of Money, that I have been Obliged to pledge my personal Credit very deeply, in a variety of instances, besides borrowing Money from my Friends; and . . . every Shilling of my own.”

But finally, fate was on the Americans’ side. After a week of bombardment by allied artillery, the trapped British, unable to obtain supplies or reinforcements, were forced to surrender on October 19. In a stunning display that would have been nearly impossible to envision without the help of Robert Morris, Cornwallis’s surrendering troops marched out of Yorktown between two mile-long lines of American and French soldiers and stacked their guns in a pile, so the story goes, as a military band played “The World Turned Upside Down.” Cornwallis was too embarrassed to join the ceremony. The final formal peace treaty between Great Britain and the United States wouldn’t be signed for nearly another two years, but in that moment, the war was essentially over and America was symbolically free.

On November 3, 1781, Robert Morris watched the awe-inspiring sight of the twenty-four battle flags seized from the surrendering British at Yorktown being paraded into Philadelphia, the capital of the infant nation of the United States. Each flag was carried by a separate American light horseman.

Robert Morris, George Washington, and Haym Salomon, immortalized in a Chicago statue. These two patriots handled Washington’s money. Without them, there might not be a United States. (dreamstime.com)

Morris described the triumphant scene that his partnership with George Washington helped engineer: “The American and French flags preceded the captured trophies, which were conducted to the State House, where they were presented to Congress, who were sitting; and many of the members tell me, that instead of viewing the transaction as a mere matter of joyful ceremony, which they expected to do, they instantly felt themselves impressed with ideas of the most solemn nature. It brought to their minds the distresses our country has been exposed to, the calamities we have repeatedly suffered, the perilous situations which our affairs have almost always been in; and they could not but recollect the threats of Lord North that he would bring America to his feet on unconditional terms of submission.”

When the war officially ended in 1783, another crisis arose. Many American troops hadn’t been paid in a year, as a bankrupt Congress could only afford basic provisions. Robert Morris, true to form, came up with a creative solution, one that the troops agreed to: a down payment, and certificates for three months’ pay to be honored by the states in six months, underwritten by Morris’s personal credit. Before leaving government in November 1784, Morris saw his scheme for a national bank approved by Congress, and the idea became the Bank of North America, an institution that helped stabilize the colonial economy.

A full-time entrepreneur once again, Robert Morris plunged into a whirl of deals and start-up ventures—canal companies, steam engines, the first iron rolling mill in America, and a scheme to corner the American tobacco market. He and a group of investors loaded up a ship with ginseng, which was cheap to pick in America and highly prized in Asia, called it The Empress of China, and sent it from New York to China, yielding a huge profit and launching the age of trade with China.

In 1787, as the first united American experiment under the weak Articles of Confederation proved a failure, Robert Morris returned to national politics, and teamed up with George Washington, James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and others at the Constitutional Convention at Philadelphia to reengineer the government on the foundations of free enterprise and strong financial authority. Morris was, in fact, one of only two people who signed all three founding documents—the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, and the U.S. Constitution.

The U.S. Constitution they created was a blueprint for prosperity, a remarkably forward-looking and enduring document that established a single currency, clear taxing power, a single unified commercial market without interstate taxes or tariffs, a market for government securities, and a central bank. It also protected intellectual property and launched post offices and roads. The document set the stage for an economic boom that continued for the next 230 years, which was powered in large part by entrepreneurs. Robert Morris was George Washington’s co-architect of both the American Revolution and the U.S. Constitution, and the most powerful executive in the revolutionary government. And as Robert Morris’s biographer Charles Rappleye put it, Morris “laid the foundation that set America on its course to becoming the economic powerhouse it is today.”

When the Constitution went into effect in 1789, president-elect Washington wanted Morris to take the job as the new nation’s first secretary of the Treasury. But Morris had an even better idea, writing to Washington, “I can recommend a far cleverer fellow than I am for your minister of finance, your former aide-de-camp, Colonel [Alexander] Hamilton.” Morris became a senator from Pennsylvania instead.

At the same time the new government was being set up, Robert Morris made the biggest mistake of his life. He decided to become a real estate mogul. He overspent so much on a superluxury town house made of marble and designed by French architect Pierre Charles L’Enfant that the local folks in Philadelphia made fun of him behind his back, even though President Washington lived there during his second administration as Morris’s guest. Another architect dismissed the building as a “monster,” and it was “impossible to decide which of the two is the maddest, the architect, or his employer,” adding, “Both have been ruined by it.”

Even worse, Morris gambled everything he had—all his savings and all his credit—on buying six million acres of land throughout the former colonies, in hopes that the value would skyrocket fast in the new nation. It did, but not fast enough for Morris. He was America’s biggest landowner, but he couldn’t find enough liquid capital to pay his bills. His income could never keep pace with his vastly inflated credit. Morris had trouble collecting back rents and attracting tenants. His health suffered.

In 1787, the world started crashing down on Robert Morris’s head. The Bank of England failed and cut off credit throughout the transatlantic markets, leaving Morris vastly overextended. “Who in God’s name has all the Money?” Morris lamented. It seemed like he owed everybody. “His complicated system of paper juggling, kiting of promissory notes, interlocking partnerships, land options, loan mortgages and speculation in every conceivable commodity collapsed,” wrote journalist Albert Southwick, “leaving him and his partner in arrears by more than 34 million dollars—a vast amount in 1797.”

The once-richest man in North America stopped going out in public to avoid being arrested, barricaded his front door, and sat inside his house holding a fowling piece, a precursor to the shotgun. He kept the bill collectors and process servers at bay for three months before surrendering to sheriff’s deputies on February 15, 1798. He was hauled off to a squalid prison cell in the debtors’ wing of the Prune Street Jail, where he stayed until bankruptcy laws were passed in late 1801.

For nearly three years, Robert Morris suffered a fate like the infamous Bernie Madoff did centuries later—he was a jailbird. It was a terrible fall for a Founding Father. But unlike Madoff, Morris was not a scam artist preying on the innocent, but an entrepreneur who dreamed far too high and, like Icarus, got burned. He took it all stoically, noting while in prison that “a man that cannot hear and face misfortune should not run risks.”

Morris died, penniless and in obscurity, in 1803, one of the least-remembered yet most consequential of our Founding Fathers.

By 1795, less than six years after George Washington took charge of a bankrupt, debt-ridden new nation, his government created a roaring engine of economic prosperity.

Washington had a vision for the economic development and prosperity of the United States, and he delivered on it. In the words of the Dutch bankers who handled America’s foreign loans, America’s credit rating was higher than “any European power whatever.” U.S. government bonds sold at a premium in European markets.

How did Washington do it? He engineered the creation of a government with strong tax and customs powers and an effective currency and monetary system, and he appointed a young New York banker named Alexander Hamilton to be secretary of the Treasury. Hamilton proved to be a brilliant choice—and, in 2015, the inspiration for a smash-hit Broadway musical. He also authorized the creation of the Bank of the United States, which helped create a money supply that was more stable than that of most European nations.

In 1794, when rebellious frontier citizens in Pennsylvania rioted to protest a crucial federal liquor tax, Washington, as a sitting president, actually mounted a saddle and led a strike force of thirteen thousand militia troops on a road march out to crush the insurrection, which threatened to cripple the government and the economy. The very thought of the Big Man on horseback was enough to scatter and eliminate the rebellion before Washington ever got there. Problem solved. Clearly, this man meant business.

Washington, in short, put the nation on a path that unleashed the entrepreneurial and free market destiny of the new nation.

Back at Washington’s Mount Vernon estate, though, which he managed part-time by long distance while he was president, things didn’t always go swimmingly. Employees boozing on the job was a big problem. In 1793 Washington was forced to fire his farm overseer Anthony Whitting because he “drank freely,” “kept bad company at my house,” and “was a very debauched person.” Earlier, in 1785, Washington had fired his gristmill manager William Roberts for being an “intolerable sot,” or alcoholic, then in 1799 rehired him after extracting a promise from him to not have a drop until the day he died. He showed up for work unable to function and half-dead from drink.

When he left the presidency in 1797 and returned to Mount Vernon as a full-time entrepreneur at age sixty-five, Washington added brand-new start-up ventures to his portfolio of breeding sheep, hogs, cattle, and deer for profit, and a whiskey distillery, which soon became one of the biggest distilleries in the new nation. He made the product from crops he grew in his own fields, processed in his own gristmill, and the abundant river water that flowed past the property, and, as a Virginia magazine described it, “rye, malted barley and corn were mixed with boiling water to make a mash in 120 gallon barrels.”

Washington had no prior experience in the whiskey business, but he studied it carefully. His timing was lucky, and he cashed in on a big shift in market tastes. Until then, rum was the preferred American drink, but whiskey was experiencing a burst of growth, and Washington’s distillery could barely keep up with demand. Within two years he was pumping out eleven thousand gallons of rye whiskey a year and operating five copper-pot stills at full blast for twelve months a year. Washington risked a major investment in the venture, and it soon became his most profitable business segment. By now his land holdings in Virginia, Ohio, Maryland, Pennsylvania, Kentucky, and the Northwest Territories exceeded fifty thousand acres.

When he died in early December 1799, America’s founding entrepreneur George Washington was busy with business plans for the new century, his mind abuzz with ideas for livestock management, fertilizers, fencing, building repairs, and crop plantings.

One night in 1798, Washington had stopped by to have a modest meal with Robert Morris, his good friend and cofounder of the United States of America, in Morris’s prison cell. “In his new buff uniform and his spanking new epaulets, the general must have been a startling contrast to the prisoner,” wrote John Dos Passos, and Washington found Morris “pale and shrunken.” Washington, moved by Morris’s plight, offered to put him and his wife up at Mount Vernon when the sentence was over, but Washington died before that would come to pass.

Of all the leaders of the American Revolution, George Washington liked Robert Morris the most.

It’s easy to see why—without the partnership of these two entrepreneurs, the United States probably never would have happened.