The Americans always display a free, original and inventive power of mind.

—Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, 1836

Now that America was liberated, its people were free to pursue their dreams of prosperity in a vast, wide-open new marketplace of ideas, opportunities, products, ventures—and risks.

There were houses, farmsteads, and factories to build, fields to clear and plant, and transportation and communications networks to lay down. And American entrepreneurs provided much of the brains and muscle power for the incredible burst of energy and achievement that rolled across the land, from the end of the revolution through the beginning of the Civil War.

When the first European settlers penetrated far into the wilderness, many of them were following their destiny as entrepreneurs.

Take the famous Daniel Boone, for example. He was the ultimate Pioneer Man, a Revolutionary War–era hunter, trapper, and real estate speculator who launched moneymaking ventures in remote, little-explored Kentucky and Missouri. According to historian Roger McGrath, “Boone was an entrepreneur, a man on the make. He stretched the boundaries of society and law; he accumulated wealth through discovery and adventure and by violent struggle with the Indians.”

Waves of settler entrepreneurs followed Boone into the wilderness, pushed farther west, and forged the Oregon and California Trails across what is now Wyoming, and the Santa Fe Trail, which stretched nine hundred miles, all the way from Missouri to New Mexico. Small family businesses and trading posts popped up along the trails to service the new travelers and populations.

From 1825 to 1840, an annual fur trading fair called the Rocky Mountain Rendezvous was held in present-day Utah and Wyoming, and brought together Native Americans, white trappers, and their families. According to one participant, the big event featured “mirth, songs, dancing, shouting, trading, running, jumping, singing, racing, target-shooting, yarns, frolic, with all sorts of extravagances that white men or Indians could invent.”

As American entrepreneurship grew along with a flurry of new inventions, changes came at lightning speed. In 1830 railroads were practically unknown. By 1860 there were more than 36,000 miles of track laid all across the nation. “It’s a great sight to see a large train get underway,” marveled nineteen-year-old New Yorker George Templeton Strong in 1839. “I know of nothing that would more strongly impress our great-great grandfathers with an idea of their descendants’ progress in science.” He continued, “Just imagine such a concern rushing unexpectedly by a stranger to the invention on a dark night, whizzing and rattling and panting, with its fiery surface gleaming in front, its chimney vomiting fiery smoke above, and its long train of cars rushing along behind like the body and tail of a gigantic dragon—or like the devil himself—and all darting forward at the rate of twenty miles an hour. Whew!”

Steamboats, pioneered by entrepreneur Robert Fulton, soon linked cities and continents together with speed and reliability. The man-made Erie Canal linked New York City with the Great Lakes, creating a monumental shift in commerce. “You talk of making a canal three hundred and fifty miles through wilderness!” exclaimed Thomas Jefferson when he first heard of the scheme. “It is a splendid project, and may be executed a century hence. It is little short of madness to think of it at this day.” Instead of one hundred years to build, it took only seven.

With the biblical phrase “What hath God wrought!” inventor and entrepreneur Samuel Morse introduced the blockbuster technology of the telegraph in an 1844 test communication between Washington and Baltimore, launching the age of instant long-distance communication a full 150 years before the takeoff of the Internet. He earned a fortune on his creation and deserved every penny—he was the symbolic godfather of the telephone, fax machine, and Internet!

Powered by telegraph communications, daily newspapers quickly followed, feeding the appetite of an information-hungry nation. With inventor-entrepreneur Cyrus McCormick’s new mechanical reaper, American agriculture was completely transformed, and the Midwest became the nation’s breadbasket. “In 1839 only eighty bushels of wheat were shipped out of the infant town of Chicago,” wrote historian John Steele Gordon. “Ten years later Chicago shipped two million.”

In 1835, a young entrepreneur named Samuel Colt created the Patent Arms Manufacturing Company in Paterson, New Jersey, and registered his first patent. His big idea was a handgun featuring a revolving automatic chamber that fired multiple shots without having to be reloaded. Previously, a single-shot weapon took some twenty seconds to reload, which spelled doom if you were a settler or soldier under attack, for example, by native warriors who in the same amount of time could fire off six arrows or chase you down with a tomahawk.

At first, Colt’s guns were prone to misfires, flameouts, and breakdowns, but by the 1850s he’d worked out the bugs with precision manufacturing based on interchangeable parts, automation, and mass production. His revolver became the standard weapon for lawmen, the military, cowboys—and quite a few desperadoes, too. Texas Ranger Samuel Walker called Colt’s pistols “the most perfect weapon in the World,” and for better or worse, the weapons helped forge the westward expansion of white settlers.

By the 1880s, the obliteration of the Great Plains buffalo herds, powered by firearms technology created by American inventors and entrepreneurs, had destroyed the traditional Native American trading patterns and hastened the collapse of Native American cultures.

“The world is going too fast,” wrote one old-timer, a sixty-nine-year-old former mayor of New York named Philip Hone. “Railroads, steamers, packets, race against time,” he lamented. “Oh, for the good old days of heavy post coaches and speed at the rate of six miles an hour!”

This giant leap of commerce and expansion transformed the lives of millions of people for the better, but had awful consequences for millions of others, including slaves of African ancestry and the increasingly beleaguered and oppressed Native American populations.

One entrepreneur’s labor-saving invention, Eli Whitney’s cotton gin, changed the world of agriculture and ignited the South’s production of cotton, which soared from 1 percent of the world’s total in 1793 to almost 70 percent of the world’s total in 1850—but by doing so it helped prolong the horrors of slavery in America.

One day in 1872, seven years after the end of the Civil War, an American entrepreneur in San Francisco came up with a blockbuster idea that capitalized on all that cotton being harvested by Eli Whitney’s cotton gins.

Millions of settlers, farmers, miners, laborers, cowboys, and lumberjacks were pouring into the West. They needed pants. Not the hodgepodge of often low-quality khaki, wool, and other choices then on the market. Good, durable pants. Affordable pants.

So Levi Strauss, a Jewish immigrant from Europe who owned a dry-goods store in the city, along with his partner, a tailor named Jacob Davis, invented blue jean pants and waist-high work overalls. They were made of rivet-reinforced, sturdy denim cotton.

The fashion world would never be the same again.

The jeans caught on like wildfire, and achieved immortality as symbols of the freedom, independence, and studly good looks of the rugged American West.

The destiny of an American entrepreneur can sometimes be fixed in a single moment of insight, a moment that changes the world of business.

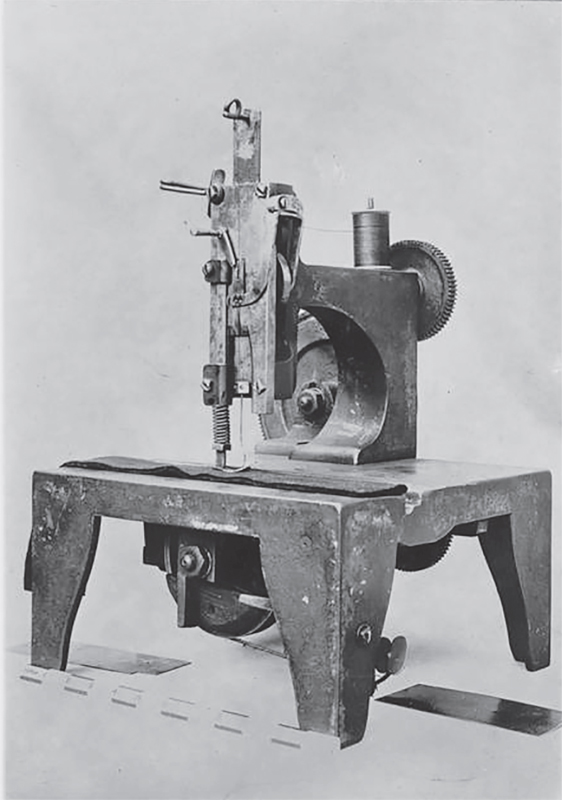

That’s what happened to Isaac Singer, a tall, boisterous, self-styled inventor and notorious womanizer (with no fewer than eighteen children out of wedlock) one day in Boston in 1850, when a machinist asked him to help improve a sewing machine. Singer thought about it for a while, gazed at the machine, and got two Big Ideas. He installed a foot pedal for feeding fabric faster, and a tower arm that held the needle over the worktable.

Bingo. America’s first multinational consumer product company was born. Until that point in history, clothes were sewn by hand. The Singer sewing machine could produce nine hundred stitches per minute, more than twenty times faster than the speed of a professional seamstress. Singer hit the road selling the product, appearing at circuses and county fairs, singing a sales song at the top of his lungs while an attractive woman conducted a demonstration of the machine.

Singer made the product more compact and lightweight, and manufacturing innovations enabled him to sell the machine at ten dollars each, affordable to the average housewife. Sales took off in the United States and, eventually, around the world, reaching near-monopoly status. Singer and his partner, Edward Clark, took trade-ins, and set up installment payment plans and sales and service networks.

An original Singer sewing machine. (New York Public Library)

When Singer died in 1875 at his British estate, he was a rich man—and the lives of many millions of people were improved.

After Robert Morris’s flameout into oblivion at the turn of the eighteenth century, America’s next genuine tycoon and millionaire was Stephen Girard, who turned a small shipping business into one of America’s biggest fortunes.

The son of a French sea captain, Girard struck out on his own in hopes of prospering as an international trader. In early 1776, when he was twenty-six, his single-masted sloop was chased into the port of Philadelphia by a British warship, and he fell in love with his new land. America, it seemed, offered all kinds of opportunities to an immigrant entrepreneur, so he decided to stick around. He opened a store, then a thriving shipping business, specializing in transporting cargo to the West Indies and New Orleans, where his language skills with French-speaking businessmen came in handy.

After the American Revolution, Girard’s trading empire flourished. He cashed in on the booming new American trade with China, and he became a much-admired employer. “Many young boys who served valuable apprenticeships in his counting house praised him,” wrote historians Robert Wright and David Cowen. “A successful stint with Girard was the 18th century equivalent of an MBA.” They added, “He found just the right mix of fixed salary and bonus incentive to keep employees productive.” Girard was a shrewd, highly calculating executive with a knack for hard work and a sharp nose for profitable deal-making.

In 1793, Girard stepped in to serve a heroic role when a deadly yellow fever hit Philadelphia, the U.S. capital, which then had a population of 45,000. Girard stayed in town while most other well-to-do people fled. He set up a hospital, rolled up his sleeves, helped care for the sick and dying, and is credited with helping to save thousands of lives. “Fearlessly, audaciously and defiantly, unselfishly serving others, he had looked death in the eye,” wrote his biographer George Wilson.

By 1812, Girard was worth $7 million, the equivalent of some $100 million today. “His sailors were among the healthiest and happiest in the world, allowing him to keep his ships at sea a larger percentage of the time than other merchants,” wrote historians Wright and Cowen. “It wasn’t unusual for his ships to leave Philadelphia laden with $75,000 worth of produce and to return a year and a half later bearing goods that would sell for $150,000 or more. He purchased sugar from specific hills that he knew to yield only the sweetest canes, and as a connoisseur of coffee and tobacco he was unequaled.”

Girard wasn’t just a pioneer in shipping and philanthropy; he was a financial genius, too. In 1811, when Girard and his partners bought what was left of the now-failed public First Bank of the United States and relaunched it as a private bank, he created a financing mechanism that kick-started many new entrepreneurial ventures. “It was a simple but brilliant plan,” noted author Greg Reid, who explained, “Using his own money and some of the best people in the banking business, he instituted conservative lending policies that allowed him to have less gold and silver on hand than other banks while making more loans to small businesses that were neglected by competitors.”

When the U.S. government ran out of money in the wake of the War of 1812, and with no national bank for the government to turn to, Girard came to the rescue by accepting federal deposits, and underwrote much of the war effort. In 1822, he gave a cash-strapped President James Monroe a $40,000 loan. In 1829, he bailed out the Pennsylvania government with a $100,000 loan to avoid bankruptcy. He made profitable early investments in the new American industries of railroads and coal mining.

When he died in 1831, immigrant entrepreneur Stephen Girard had built an estate that was later estimated at the modern equivalent of $200 million.

But he is probably best remembered for starting Girard College, a school that has for 168 years helped educate thousands of children in need. When Girard signed the documents to establish the school, it was the biggest charitable donation in American history.

American entrepreneurs have always had a special knack for bold ideas.

Some of these ideas have seemed, at first, to be downright wacky.

In my family’s case, for example, the idea was that people would spend a million dollars on hand-made duck calls. If you’d heard that pitch back in the 1980s, you might be forgiven for thinking we had a few screws loose. But after thirty years of hard work, we did it.

Another case is the amazing story of Frederic Tudor, who, in 1806 at age twenty-three, came up with an equally implausible concept in the days before refrigeration and electricity—“Cut giant blocks of ice out of frozen New England lakes and ship them all over the world and make a bundle of money!” He pulled it off, too.

The third son of a wealthy Boston lawyer and his wife who kept an underground icehouse out back, as many New England families did, Tudor joined the family on a Caribbean vacation, where ice was an unknown commodity. He put two and two together and figured, Why not just ship ice to the tropics and sell it? Well, that was a lot easier said than done. His rich father was skeptical, but helped stake him in his first venture, in which he bought a two-masted, square-rigged ship and hauled a cargo of 130 tons of ice down to the tropics, insulated with straw and hay.

It seemed such a nutty scheme that the Boston Gazette published the headline “No Joke, Ship Full of Ice Sets Sail for Martinique.” The snarky subheading cracked: “Let’s Hope This Doesn’t Prove to Be a Slippery Speculation!” When Tudor arrived at his destination, some of the ice had already melted. Potential customers there couldn’t have cared less, plus there was nowhere to store the stuff. Tudor took a bath on the deal, losing the equivalent of $90,000 today.

But like many an American entrepreneur ever since, once Frederic Tudor had a big idea, he just wouldn’t let go of it. He kept tinkering, tweaking, and trying for the big payoff. And destiny kept slamming the door in his face. Over the next ten years, he lost money, dodged creditors, and wound up in debtor’s prison more than once. His biographer Steven Johnson wrote that Tudor “assumed the absolute novelty of ice would be a point in his favor,” but he “instead, received blank stares.” The depressing pattern of failure repeated itself, with reliably disastrous results. “For most of his early adulthood,” wrote Johnson of Tudor, “he was an abject failure, albeit one with remarkable tenacity.” He couldn’t go back to his father for help, since his father had gambled away the family holdings on bad investments.

Tudor had three big barriers to success. First, few people in the tropics really cared about having ice, and they sure didn’t care to pay for it. Second, it’s a hugely labor-intensive process to cut big blocks of ice out of a lake that’s frozen solid. And last but not least, no one had figured out how to prevent ice from melting on a long ocean voyage.

Through constant experimentation and trial and error, Tudor eventually cracked all three problems. First, to stimulate demand, he gave out free samples to bartenders. “The object is to make the whole population use cold drinks instead of warm or tepid,” Tudor wrote in his diary. “A single conspicuous bar keeper, selling steadily his liquors all cold without an increase in price, render it absolutely necessary that the others come to it or lose their customers.”

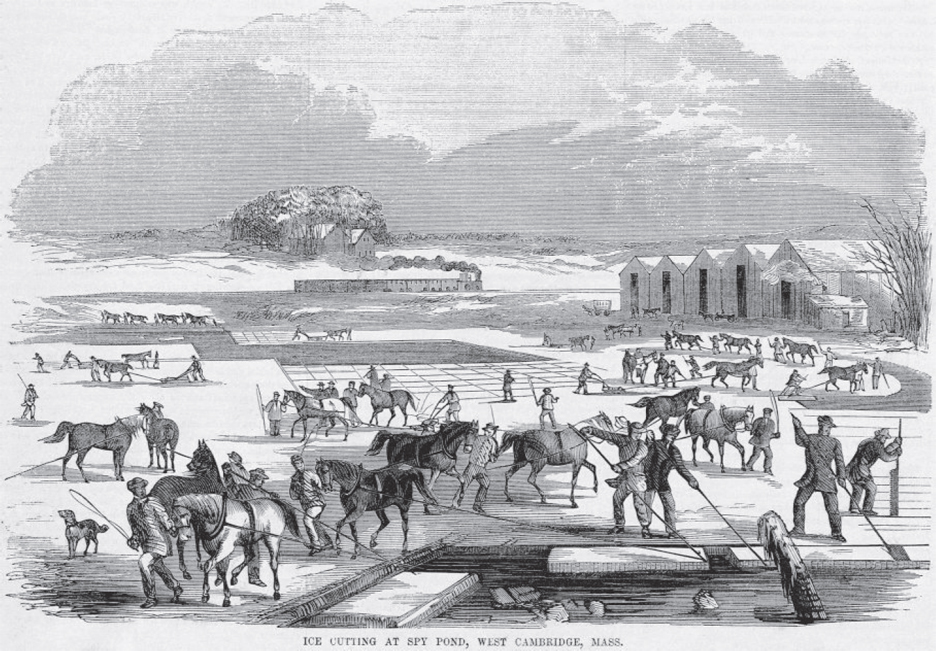

Second, to cut labor costs, Tudor used a new horse-drawn two-bladed ice plow that cut deep into the ice much more efficiently than human-powered handsaws and pickaxes. And third, instead of straw and hay, he used layers of sawdust to insulate the ice on long voyages, which worked surprisingly well.

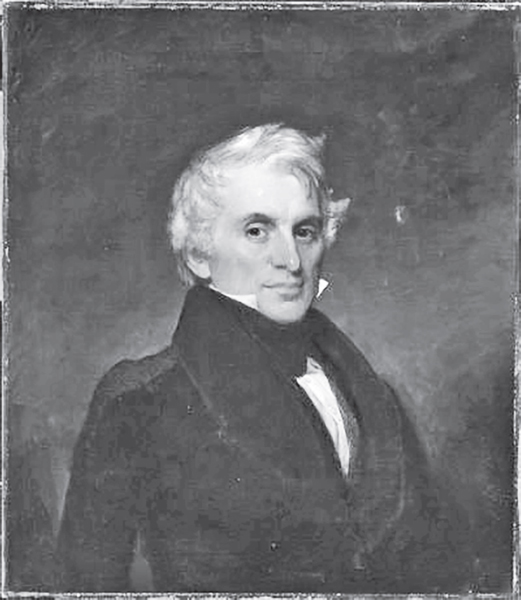

The Ice King: this dapper fellow, Frederic Tudor, built an early American business empire on an unusual idea—selling ice to global customers in the days before electricity and refrigeration. (Francis Alexander, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

Absorbing the lesson of his Martinique fiasco, a year later he made a deal in Cuba that pre-positioned an icehouse there before he docked his cargo. This time, it worked. Eventually, he got ice-supply monopolies in Cuba and Jamaica, and shipped loads of ice all over the hot, humid American South, too.

As labor-intensive agricultural industries grew in the blazing-hot tropics, so did the demand for icy refreshment, and Tudor cashed in. In 1833, Tudor pulled off a major coup—he managed to ship a 180-ton load of ice from Boston all the way to Calcutta, a 16,000-mile trip that took four months. Most of the stash survived unmelted, and the shipment caused a sensation among the British expat population in Calcutta, who held chilled wine and beer parties to celebrate. Profits rolled in.

By 1856, Tudor’s success attracted competition, and the ice-shipping business was booming globally. Over 150,000 tons of ice per year was being shipped from New England to more than forty countries as far away as Japan, Australia, Singapore, and Brazil, and railroads hauled ice all over the United States.

Ice-cutting crews in Cambridge, Massachusetts. (Wikimedia Commons)

During the winter of 1846–47, the great writer Henry David Thoreau looked out his window and spotted a team of Tudor’s ice-cutters on his beloved Walden Pond, creating chunks of frozen water bound for distant lands. Pondering the weirdness of the scene, he wrote, “The sweltering inhabitants of Charleston and New Orleans, of Madras and Bombay and Calcutta, drink at my well.” He added, “The pure Walden water is mingled with the sacred water of the Ganges.”

The ice-shipping industry evaporated once refrigeration technology arrived, but by then, the stubborn, tenacious, and multiple failed founder of it all had made a huge impact. “Tudor’s big idea ended up altering the course of history, making it possible not only to serve barflies cool mint juleps in the dead of summer, but to dramatically extend the shelf life and reach of food,” wrote journalist Leon Neyfakh. “Suddenly people could eat perishable fruits, vegetables, and meat produced far from their homes. Ice built a new kind of infrastructure that would ultimately become the cold, shiny basis for the entire modern food industry.”

Frederic Tudor, the American entrepreneur with what seemed to be a truly wacky brainstorm, died at age eighty, with a net worth of $200 million in today’s money.

Some American entrepreneurs weren’t above cutting corners or breaking the rules to gain a competitive edge.

One extreme example of this is Francis Cabot Lowell, a Massachusetts merchant who managed to both build a fortune for himself and help launch the Industrial Revolution in America, all based on a single, sneaky act of industrial espionage.

The year was 1811. Lowell, then a leading Boston importer of British textiles, was taking a long, leisurely grand tour around England with his family. Along the way, he stopped frequently to tour textile factories, examining the state-of-the-art high-speed weaving and spinning machines powered by water and steam. At the time, England had strict controls in place to protect its patent-protected trade secrets and advanced industrial technology. It was a serious crime to buy, copy, or share industrial designs. Skilled machinists and textile workers were forbidden from leaving the country. Few outsiders were allowed into the factories.

But the British made an exception for Lowell, who was a big customer of the British textile bosses, and a good friend to boot. Or so they thought. What they didn’t know was that the crafty entrepreneur realized he could make more money if he “stole” the British textile-making technology and manufactured clothing himself, back in the States, rather than paying top dollar at full retail prices for finished goods shipped over from the mother country.

During the tours, Lowell carefully studied the British power looms and spinning machines, and took special note of how the Brits outsourced sections of the production system to different teams with specialized tasks. He memorized everything. He didn’t use paper and pencil, but he created blueprints in his mind and filed them away. Lowell’s behavior eventually got so suspicious that in the summer of 1812, his ocean voyage home to Massachusetts was blocked by British warships, which detained him in Canada. Officials searched his luggage but they found nothing incriminating, of course: it was all tucked away in his brain.

Once back home, Lowell put the stolen technology right to work by building the world’s first fully integrated textile mill on the banks of the Charles River in Waltham, Massachusetts. Soon he was shipping finished cotton goods across the country. The idea of a fully integrated factory that processed raw materials into a finished product was brilliant, and it helped trigger the wave of American mass-production manufacturing that transformed the nation. Over the next century, textiles became a dominant industry in New England.

And it all happened thanks to an act of business spycraft. As journalist Howard Anderson put it, “The father of the American Industrial Revolution wasn’t an inventor, or even a financier. He was a thief—a Brahmin thief (Exeter, Harvard), but a thief nonetheless. What did he steal? Intellectual property.”

One day in 1783, just as the whipped British were packing up and heading home, a young butcher’s son from Germany named John Jacob Astor stepped off a ship and hit the streets of New York City, intent on making a fortune.

He carried a suitcase containing seven flutes, and he planned to get into the business of selling musical instruments. When he died sixty-five years later, he was the richest man in the nation. He didn’t do it with flutes.

Astor started off hawking rolls and cakes on the sidewalks of Manhattan, then took a job with a fur merchant, scraping and cleaning undressed fur pelts in lower Manhattan, then beating them to scare off the moths.

Astor had a secret weapon that is common to many successful entrepreneurs (myself included!): the support of a strong, brilliant spouse. Two years after arriving in America, he married Sarah Cox Todd, the daughter of Scottish immigrants, a woman who Astor soon realized was smarter than most merchants. She became his behind-the-scenes, hands-on business partner. They opened up a shop on Water Street that traded furs and sold musical instruments. They worked very hard and lived frugally.

Seeing a bigger future in fur than flutes, Astor switched to fur trading full-time, specializing in high-fashion beaver, marten, mink, and otter pelts, which were popular in fashionable society circles in New York and London.

Astor’s fur-buying trips took him all over the Midwest and Canada, and he learned the languages of his Native American trading partners. “John Jacob was a canny trader,” wrote biographer Axel Madsen. “Few trappers or Indians got the better of him. He did it all himself, hauling the furs back to Albany, baling and loading them on barges down to New York for reshipment to London. The profits were as much as 1,000%.”

By 1800, John Jacob Astor was the top American merchant in the fur trade, and he launched a shipping business to capitalize on the booming trade with China. He orchestrated at least one illegal drug deal, in 1816, a profitable shipment of ten tons of opium from the Ottoman Empire to China, making him, in effect, a drug trafficker. With his profits from the fur and shipping businesses, he started dabbling in New York real estate.

In 1808, Astor had an idea. It was the kind of idea that American entrepreneurs have had for centuries—so outlandish that it just might work. Astor thought he could connect America, Asia, Russia, and Europe all together into a global business powerhouse, a new commercial empire based on a special ingredient—animal hair. “His innovation,” reported journalist Peter Stark, “was to link the interior North American fur trade over the Rockies with the Pacific coastal fur trade and link that to the Russian Alaskan fur trade, and link that to China, to London, to Paris, to New York. Astor’s thinking revolved on entire continents and oceans.”

Astor was already a highly successful fur trader, and had started dabbling in New York real estate, but now he saw the promise of fantastic riches in the new territory of the Louisiana Purchase, land that was recently explored by the epic Lewis and Clark expedition.

Astor’s brainstorm was to set up a trading center on the remote, little-explored Pacific coast of North America, an area that was rich in high-value beaver, lynx, fox, and bear furs, and especially in sea otter furs, which were highly prized in the Chinese market. Astor’s ships would go from New York all the way around Cape Horn to Oregon, and drop off manufactured goods to trade with Native American trappers and suppliers in the Pacific Northwest. Then the ships would take the furs over to China, and carry back Chinese goods like porcelain, silk, and tea to New York, for sale in the U.S. and European markets. Markups were huge. For example, a sea otter pelt could be bought for the modern equivalent of one dollar from coastal Native Americans, then sold for the equivalent of $100 in China.

This early American entrepreneur was thinking on a truly global scale, way ahead of his time. As historian James Ronda put it, Astor was “relentless in the pursuit of wealth” and a business genius who “embraced business techniques far in advance of his contemporaries.”

John Jacob Astor: America’s first great business tycoon started off running a store in lower Manhattan with his wife that sold furs and musical instruments. (Painting by John Wesley Jarvis)

As it happened, President Thomas Jefferson loved the idea of a new Pacific trading post and offered his strong moral support. A successful settlement in Oregon based on the lucrative, booming fur business would strengthen the United States’ claim to the region and muscle out the fast-encroaching Canadians. “The beaver became a factor of empire, and battles were fought and treaties delayed over who was to control access to prime trapping areas,” wrote historian James Stokesbury. “The future of North America depended on the flashing paddle and the beaver trap as much as it did on muskets and bayonets.” President Jefferson was highly impressed by John Jacob Astor’s energy and vision, and pitched in to help the wheeler-dealer from New York. In a letter to Meriwether Lewis in 1808, when Astor was planning the logistics of his outpost on the Columbia River, Jefferson called Astor “a most excellent man,” “long engaged in the [fur] business & perfectly master of it.”

But from a practical point of view, Astor’s plan for the “Pacific Fur Company” started off as a slow-motion disaster. He sent out two expeditions, one by land and one by sea, into the largely unknown, often savage wilderness, to link up at the mouth of the Columbia River. In Oregon, the oceangoing contingent carried construction materials to build a settlement and headed around Cape Horn and up the Pacific coast.

Both groups ran into big trouble. Around the area now known as Hell’s Canyon on the Snake River in Idaho and Oregon, the overland group faced starvation and tough natural barriers like rapids and endless flatlands. Many members of the ship-bound party were killed by Native Americans. All told, the journeys killed more than sixty of the employees Astor sent to set up the outpost.

Both teams, or what was left of them, eventually made it to the rendezvous point, and by 1811, incredibly, they actually got the business going. The settlement was called Fort Astoria, and soon Astor’s complex global trading scheme was raking in money hand over fist.

Then, in an instant, it was over.

In the wake of the War of 1812, a Canadian expedition, commissioned by the British government in Canada, showed up and demanded that Astoria be handed over to a Canadian company, or else. Astor’s representative, fearing a military seizure by the Royal Navy of the remote, lightly defended operation, panicked and sold off the fort at a bargain-basement price.

Astor was furious, but there was nothing he could do. He abandoned the Asia venture and got right back to work. During the War of 1812, he bought American ships cheap when they were stuck at the docks, and sold them high when the war ended and business picked up. He also loaned the U.S. government millions of dollars and made a tidy profit on the payback when the war was over. “By the end of the war, the United States government was on the brink of bankruptcy,” wrote Stokesbury. “Astor’s response, together with a consortium of associates from Philadelphia, was to buy high-interest bonds with debased currency, and he emerged from the war in far better shape than the Federal Government. At the same time, he enlarged his New York City holdings so that by the time peace was made, Astor was immensely wealthy and ready to take over virtually the whole of the American fur trade.” In 1816, Congress gave Astor a near monopoly on the fur business in the U.S. by closing down all his foreign competitors.

When the fur business started slowing down in the 1820s, Astor figured it was a permanent trend, so he bailed out and switched to buying real estate in the Midwest, and increasingly in Manhattan, betting that land values would skyrocket as the city moved north. He guessed that New York would become the business capital of the young nation. He guessed right. He became a real estate mogul, the biggest one in early America.

When New York real estate prices plummeted during the financial panic of 1837, Astor scooped up large sections of the city at bargain prices. One deal saw him acquire a full city block, valued at $1 million, for just $2,000. Another saw him acquire a $25,000 interest in a mortgage on financially troubled Eden Farm, a twenty-two-acre property around the site of present-day Times Square. The farmer defaulted; Astor foreclosed, took possession, and sold off pieces of the property for about $5 million.

Through it all, Astor showed a key entrepreneurial skill—he had a remarkable sense of timing, for when to get in and out of a deal, and how and when to invest. “Astor was able to recognize opportunities in a lot of different industries,” noted Terri Lonier, a professor of entrepreneurship at Columbia College Chicago. “He knew when political, economic, and market forces were aligned so that he could maximize his investments.” Astor’s contemporary, New York mayor Philip Hone, said of him: “All he touched turned to gold, and it seemed as if fortune delighted in erecting him a monument of his unerring potency.”

Despite his fabulous wealth, Astor led a simple life focused on plain living. He rose early and worked extremely hard. When he died in 1848, just a few weeks short of his eighty-fifth birthday, Astor possessed one-fifteenth of all the personal wealth in the United States, according to one estimate. He was the wealthiest person in America, with an estate estimated at between $10 to $20 million, or around $11 and $22 billion in today’s dollars. He had only one regret. “Could I begin life again,” he is reported to have said on his deathbed, “knowing what I now know, and had money to invest, I would buy every foot of land on the island of Manhattan.” “Every dollar,” Astor once said, “is a soldier to do your bidding.” Astor’s official biographer, James Parton, called him “one of the ablest, boldest, and most successful operators that ever lived,” and his New York Herald obituary said that he had the “ingenious powers of a self-invented money-making machine.”

Like his fellow early American superentrepreneur Stephen Girard, John Jacob Astor left behind one major, lasting legacy to charity. In his will, Astor provided the start-up funds for a library that today has become one of the world’s finest centers of knowledge, and a place where much of the research for this book was done—the New York Public Library. New York City socialite Brooke Astor, the widow of John Jacob Astor’s great-great-grandson Vincent, was a trustee and honorary chairman of the library until her death in 2007 at age 105.

Today you can take the New York City subway from Astoria, Queens, transfer to the number 6 train, pass directly under the Waldorf-Astoria, and get off at the Astor Place station. All three were named in John Jacob Astor’s honor.

When you get off at Astor Place, look up at the tiled artwork on the walls of the station. It features the furry creature that made Astor’s first fortune and was the perfect symbol of the kind of man he was—a busy beaver.

On November 8, 1833, near Hightstown, New Jersey, the axle gear overheated on the forward coach car of a southbound train going 20 miles per hour.

The gearbox caught fire and broke up, causing the car behind it to derail and flip over into an embankment. There were twenty-four people inside.

The accident tossed passengers violently around the inside of the car, smashing limbs, injuring all but one of them and killing two, believed to be the first train-passenger fatalities in history.

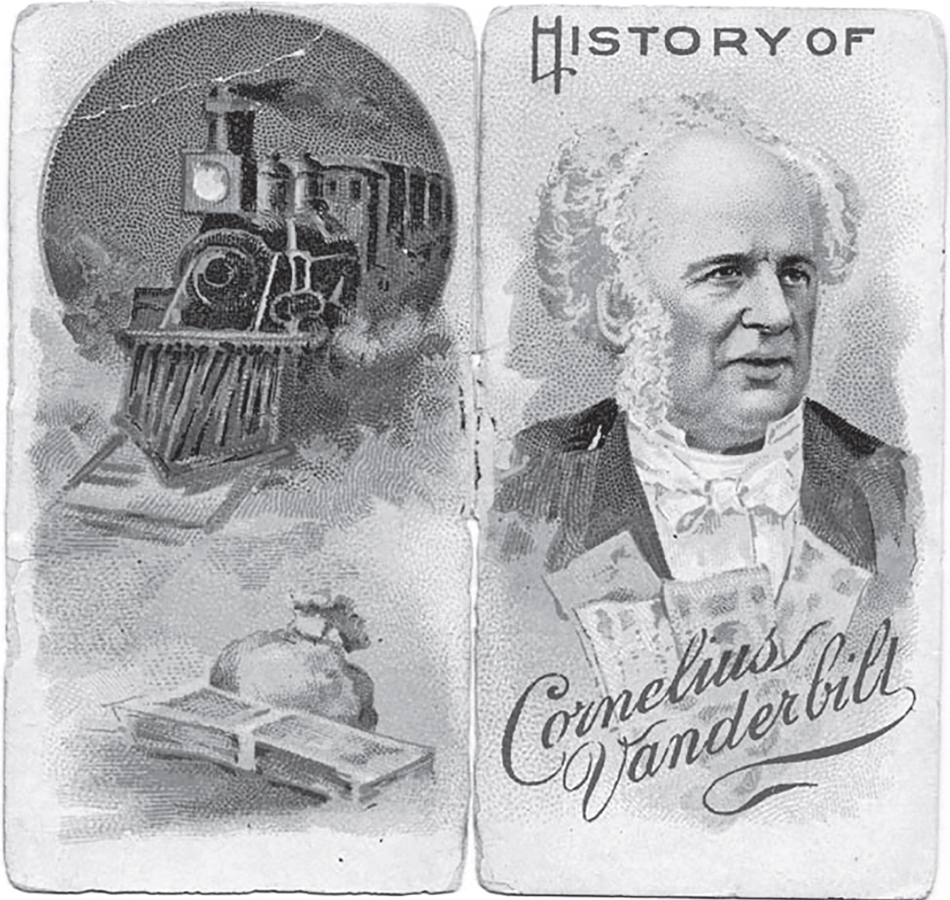

One of the passengers in the first car was former president John Quincy Adams, and one of the passengers in the car that derailed was a thirty-nine-year-old up-and-coming steamboat entrepreneur from New York named Cornelius Vanderbilt, who was heading to Philadelphia on business. It was the early days of railroading in America, and just two months after steam locomotives were installed on the line, replacing horses.

A shaken Adams described the scene he witnessed when the train crashed to a stop, writing in his diary: “The scene of sufferance was excruciating. Men, women, and a child scattered along the road, bleeding, mangled, moaning, writhing in torture, and dying, as a trial of feeling to which I had never before been called; and when the thought came over me that a few yards more of pressure on the car in which I was would have laid me a prostrate corpse like him who was before my eyes, or a cripple for life; and, more insupportable still, what if my wife and grandchild had been in the car behind me! Merciful God!”

Cornelius Vanderbilt, who was on his first railroad trip that day, was thrown out of the railroad car to the bottom of the embankment. His clothes were shredded, his leg was shattered, and one of his ribs had punctured his lung. He coughed up blood. He was sure he was about to die. And he would have died, had a skilled young local doctor not quickly ministered to him. Years later, when Vanderbilt had achieved the position as America’s great corporate tycoon, he told the doctor that he had been spared that day “to accomplish a great work that will last and remain.” That great work turned out to be laying the foundation for much of the American transportation system in the nineteenth century. As historian Michael Kazin wrote of Vanderbilt, “As a self-taught, self-made entrepreneur, he had no equal.”

Vanderbilt was born in 1794 into a poor farming family on Staten Island, from where he could see the booming pre-metropolis of Manhattan on the northern horizon. From ages ten to fifteen, he worked for his father, and for a ferry service shuttling people and cargo between the two islands.

At the age of sixteen, Vanderbilt caught the entrepreneurial bug, and it never left him. He talked his parents into lending him $100 to buy a sailboat and started a discount cargo and ferry business of his own between Staten Island and Manhattan. Mom and Dad agreed, but only if he cut them in on the action. Within one year he was able to pay them off, and give them a healthy slice of the profits as well. At eighteen, Vanderbilt struck a deal with the U.S. government to supply military stations, and by age twenty he had a fleet of vessels shuttling people and cargo all the way from Delaware Bay up to Boston.

In 1817, Vanderbilt signed on as the junior partner in a thriving new steamboat venture called the Union Line, which gave him invaluable experience in running a complex business. Steamboats were a quantum leap forward in waterborne travel, making it much more efficient, reliable—and profitable. Vanderbilt pounced on the new technology. From 1818 to 1829, Vanderbilt and his partner made a fortune, in part by undercutting the competition by as much as 75 percent, providing high-quality service, and attracting huge numbers of customers. The only trouble was that the business was technically illegal, since by bringing passengers between New Jersey and Manhattan he was violating an 1808 New York State government–approved monopoly controlled by Robert Livingston and steamboat pioneer Robert Fulton. Vanderbilt and his partner fought the monopoly all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled in their favor and found that only Congress, not state governments, had the authority to regulate interstate business.

By the time his partner died in 1829, the frugal Vanderbilt had saved enough to build his own personal navy of steamboats, an empire that eventually numbered one hundred vessels and earned him the popular nickname “Commodore,” which he loved. He expanded his routes all over the Northeast and called his service the “People’s Line,” offering cheap fares for all.

In 1851, as the California Gold Rush was taking off, Vanderbilt launched an ingenious shuttle service between the East Coast and San Francisco—by running oceangoing steamships to Nicaragua and using canoes and mule trains, and then a railroad, to haul people, mail, and gold back and forth across the land barrier. By 1861 Vanderbilt dominated both the transatlantic and transcontinental shipping lines and exerted major influence on the financial markets. Some people considered Vanderbilt to be a speculator, but he was much more than that. He was a trailblazer, a consolidator, a builder, and a long-term visionary.

In 1853, Vanderbilt took his first vacation, a grand tour of Europe in a customized personal steamship. While he was gone, he heard some associates were plotting against him. He sent them this tight, punchy message: “Gentlemen: You have undertaken to cheat me. I won’t sue you, for the law is too slow. I’ll ruin you. Yours truly, Cornelius Vanderbilt.” He once explained, “I am not afraid of my enemies, but by God, you must look out when you get among your friends.” According to his lifetime assistant, Vanderbilt “thought every man could stand watching,” and “never placed confidence in anyone.” He confided in few people and made decisions with switchblade speed. One of his business maxims was “Don’t tell anybody what you’re going to do, until you have done it.”

Critics called Vanderbilt a “robber baron” because of his aggressive, take-no-prisoners business style, and he looked the part. Vanderbilt “looked like a conqueror,” wrote Louis Auchincloss. “He had a clear complexion, ruddy cheeks, a large bold head, a strong nose, square jaw, a high, confidence-inspiring brow, and thick, long gray hair which turned magnificently white.”

Vanderbilt was at the vanguard of an elite new breed of northern businessmen who, according to historian Michael Kazin, thought their hard work helped hold the Union together. “Corporate ethics, however, were honored more in banquet rhetoric than in deeds,” wrote Kazin. “Vanderbilt and his cost-conscious brethren naturally preferred friendly negotiations to forceful or dishonest tactics. Yet when polite methods failed, they were quite willing to buy off politicians, double-cross former partners and have the police break up strikes by their workers. Although Vanderbilt habitually dressed in the simple black-and-white outfit of a Protestant clergyman, his only religion was economic power.” Historian H. Roger Grant wrote, “Contemporaries, too, often hated or feared Vanderbilt or at least considered him an unmannered brute. While Vanderbilt could be a rascal, combative and cunning, he was much more a builder than a wrecker,” who was “honorable, shrewd, and hard-working.”

Beginning in 1863 and 1864, when he was already close to seventy years old, Vanderbilt left the shipping business to launch a full-scale assault on the railroad industry, which was where, he thought, the big growth in the transportation business would be. He conducted corporate raids and buyouts of the New York Harlem and Hudson lines and the Long Island Rail Road, then went after the big prize, the New York Central Railroad, which dominated train traffic in and out of New York City. Within ten years Vanderbilt controlled much of the railroad industry that linked New York to Boston, Montreal, St. Louis, and Chicago.

Vanderbilt wasn’t mainly a builder of railroads, but a buyer, consolidator, and improver—he kept fares low and upgraded service, and he knew when to play bare-knuckled hardball. In 1867, during a business dispute, he launched a commercial blockade on America’s business capital by cutting off all rail service to New York. His enemies caved in quickly, and Vanderbilt won, as usual. In 1869, he both triggered a Wall Street panic and appeared as the hero to stop it, by bailing out companies on the edge of failing with millions of his own dollars. “Vanderbilt,” wrote his biographer T. J. Stiles, “was a paradox—both a creator and a destroyer.” According to Stiles, “Vanderbilt essentially invented the modern corporation through his purchase and consolidation of New York’s major railroads, built the first true corporate conglomerate in U.S. history,” and became the “first great corporate tycoon in American history.”

The Commodore: Despite the unfortunate hairdo, mega-entrepreneur Cornelius Vanderbilt pioneered the modern American corporation with two businesses: steamboats and railroads. (Duke Tobacco Company Cigarette Cards Collection, Wake Forest University Library)

With strong management and major investments in train track and equipment, Vanderbilt created efficient railroad passenger service—and pulled the American transportation industry into the modern era.

When Vanderbilt died in January 1877 at age eighty-two, he was, by some estimates, the second-wealthiest person in U.S. history (after Standard Oil cofounder John D. Rockefeller), with a fortune equal to roughly $200 billion in today’s dollars. The New York Times grandly proclaimed in his obituary, “Every movement of his will was perceptible in the fleets which covered the waters, or in the network of rails which enmeshed the land,” and “By him, therefore, the movements of population, the currents of trade and travel, and the requirements of commerce, must have been clearly seen and understood. It was his business, in a large way, to anticipate and meet all these requirements and changes.”

No matter how you measure it, American superentrepreneur Cornelius Vanderbilt’s impact on America was huge.

Today Vanderbilt’s steamboats and railroad cars are long gone, and most of the fortune he left to his descendants vanished long ago from family dissipation, taxes, and overspending.

In 1973, when 120 of Vanderbilt’s descendants gathered for their first family reunion, there were no millionaires in the group. “The Fifth Avenue mansions, alas, are long gone,” wrote descendant Arthur T. Vanderbilt II. “But today, if you stroll down Fifth Avenue and if the light is just right and you half close your eyes, you might spot a red carpet being unrolled from the door of a limestone chateau down the steps to the curb, watch as a burgundy Rolls-Royce stops in front and guests walk up to the door flanked by maroon-liveried footmen, and hear coming from inside the faraway sounds of an orchestra.”

There are two monuments to Vanderbilt that do endure to this day: Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, which he funded, and the railroad network of the United States that he shaped, much of which symbolically flows into the architectural masterpiece of New York’s Grand Central Terminal, the 1913 version that replaced the original building, which Vanderbilt himself completed in 1871.

On the south side of the building, overlooking Park Avenue from an elevated vehicle viaduct, is a huge bronze statue of the Commodore, weighing ten tons, striking a noble pose in a furry double-breasted coat and comically huge mutton-chop sideburns. He commissioned the statue himself. You can’t really see the statue from the street or the sidewalk, though. The view is mostly blocked by the roadway. Shortly after Grand Central opened, the New York Times, noting the regularity of railroad accidents, said any Vanderbilt statue should include “the dismembered bodies of men, women and children.”

Today, in bronze outside Grand Central, wrote architectural historian Christopher Gray, Cornelius Vanderbilt “stands a hostage, in a haze of exhaust produced by the railroad’s most potent enemy, the automobile.” The great man left behind another legacy, too. Every weeknight you can tune in to CNN and watch Cornelius Vanderbilt’s great-great-great-grandson host his own TV news show. His name is Anderson Cooper.

Back in the 1830s, harvesting grain was nearly as inefficient as it had been since the days of ancient Rome—it took a person fourteen hours to cut one acre of wheat.

Then, along came Cyrus McCormick. He grew up in a prosperous farming family who lived on an 1,800-acre property in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley. His father, who loved to tinker with machines and equipment, worked with young Cyrus to try to make an effective mechanical reaper, but couldn’t pull it off. In 1831, he turned the project entirely over to Cyrus, who was twenty-two. Within a year, Cyrus had hammered together a horse-drawn harvester that was able to chop six acres of oats in a single morning. That equaled the work of twelve men working full-out.

Cyrus offered his creation to fellow farmers at the price of about $1,400 in today’s dollars, but no one bought the funny-looking device. Farmers had been hand-cutting grain for four thousand years and saw no need for a new approach. “It’s a contraption that is seemingly a cross between a wheelbarrow, a chariot and a flying machine,” said one skeptic. Cyrus was unfazed and kept on tinkering and selling. He patented his reaper. Years went by. The financial panic of 1837 nearly bankrupted his farm. “In this hour of debt and defeat, Cyrus showed that indomitable spirit which was, more than any other one thing, the secret of his success,” wrote biographer Herbert Casson. “Without money, without credit, without customers, he founded the first of the world’s reaper factories in the little log workshop near his father’s house and continued to give exhibitions.”

Still more years went by without great success. McCormick’s first models didn’t perform too well, so he kept fiddling with them to make improvements. By 1840 he had perfected his design, and started demonstrating the new model widely, offering a money-back guarantee, which later proved really popular. By the mid-1840s, he had sold only a relative handful of mechanical reapers, but he was convinced that the westward march of settlers into vast new farmlands and the shortage of labor would eventually pay off for him. He kept plugging away.

Cyrus McCormick, who developed and marketed the first widely adopted mechanical reaper. (George Smillie)

To get closer to the growing number of potential customers in the Midwest, Cyrus moved his little factory to the new but fast-rising city of Chicago in 1847. Chicago didn’t even have paved streets yet, but it connected to the Great Lakes and to westbound trains, and the move was a logistical masterstroke. The first mayor of Chicago, a man named William Ogden, was so impressed by the potential of plucky Cyrus’s product that he chipped in with a $25,000 personal loan, which would be worth about $700,000 today.

In 1848, McCormick sold five hundred reapers. In 1849, the factory turned out 1,500 machines. In 1851, McCormick went to London to do competitive cutting with his reaper at the Crystal Palace Exhibition, site of the world’s first industrial fair, where he won a gold medal and stimulated initial European orders. By 1856, his factory was making four thousand reapers a year for domestic and foreign markets.

The Civil War, from 1861 to 1865, made McCormick’s machines essential. “The reaper is to the North what slavery is to the South,” declared Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. “By taking the place of regiments of young men in the Western harvest fields, it released them to do battle for the Union at the front and at the same time keeps up the supply of bread for the nation and its armies.”

McCormick was a master of mass manufacturing and marketing who pioneered a whole bunch of business-building techniques. He offered fast after-sales service to keep his products working smoothly and his customers happy. He ran ads and pitched product stories to magazines and newspapers. He express-shipped his product by fast rail, in easy-to-assemble sections. He experimented with franchising and hired local partners as sales and service agents and debt collectors. He offered installment payment arrangements and the money-back guarantee, both unheard of until then. He staged product demonstrations before big crowds.

The American Civil War can, in fact, be seen as a battle between the inventions of two American entrepreneurs: Eli Whitney’s cotton gin, the tool that powered the economy of the South, and Cyrus McCormick’s mechanical reaper, which was widely used in the North. “While the cotton gin had made slavery profitable, the reaper had made the Northern states wealthy and powerful,” wrote McCormick’s biographer Herbert Casson. “As the war went on, the crops in the North increased, with 200 million bushels being exported during those four years. The reaper thus not only released men to fight for the preservation of the Union, it fed them in the field and kept our credit good among foreign nations at the most critical period in our history.”

When he died at age seventy-five, Cyrus McCormick was worth $255 million in today’s money, there were some 500,000 McCormick harvesters in operation, and world agriculture had been transformed. Thanks to him, populations all over the world were freed from the danger of famine. The French Academy of Sciences honored McCormick by making him a member and for “having done more for agriculture than any other living man.” Historian Christine Heinrichs noted that “his invention made farmers’ lives better, released workers for the industrial revolution and made the biggest contribution to ending hunger around the world.”

McCormick’s final words were, “Work, work!”

The pre–Civil War entrepreneurs were mostly small-business people—traders and merchants, mom-and-pop shops, and family businesses of a few dozen employees at most. They were small, but they pioneered new landscapes and inventions and laid the foundations for a new era of growth that would soon create the world’s greatest economy.

It was time for a new breed of entrepreneurs to appear, men and women who would lift America to undreamed-of heights.

They would achieve spectacular wealth and power for themselves, and a few of them would even discover the ultimate secret of life—what God put them on earth for.