As soon as the Civil War ended, America made a giant leap to global leadership as the biggest industrial and consumer economy in the world.

American entrepreneurship and business exploded after the war. Factories that had cranked out guns and war supplies stayed open when the war ended, providing a strong platform for a gigantic manufacturing boom.

It was the age when American entrepreneurial giants grew from rags to riches as they dreamed up new markets, new products, and new worlds of business to create.

So many new inventions, innovations, and business ventures blossomed so quickly that this time, roughly between 1870 and the dawn of World War 1 in 1914, became known as the Second Industrial Revolution. Historian Gerald Gunderson reported that in this time, entrepreneurs “found it more attractive on average to develop new products in the United States than in any other economy in the world.”

It was like the United States had a sign painted across it for all the world to see: “Come on in and start your own business! Everybody’s welcome, the sky’s the limit!”

Starting your own business in the booming United States, compared to the rest of the world, was as easy as apple pie. In European countries and colonies, it often took cutting through a lot of red tape, fancy stamps and seals, political connections, and royal decrees and proclamations to open up a new shop or other business venture. If your business failed, you were considered a social outcast. If you had too many debts, you were thrown in debtor’s prison.

But over here in America, starting your own business was a simple legal procedure, going as far back as 1811 when New York State passed an incorporation law that let you do it by filling out a few forms. It was a really smooth operation. Soon the number of corporations skyrocketed. Debtor’s prisons in the United States were eliminated by federal law in 1833. Having a bankruptcy or business failure on your record didn’t mean permanent failure. You could try again. America gave entrepreneurs a precious gift—the freedom to fail!

The tragic, bloody expulsion of Native American populations across the continent created nation-size areas of fertile land that were now open to be exploited for profit. The American population grew from 40 million in 1876 to 76 million in 1900, with one-third of the increase resulting from immigration. All these people had to be fed, clothed, housed, moved, and entertained, and entrepreneurs stepped right in to meet the opportunity.

Between 1865 and 1900, thanks to railroad magnates and the thousands of entrepreneurs and workers who supplied them with goods and labor, railroads expanded from 35,000 miles of track to nearly 200,000, linking together all the major cities. By the early 1860s, commerce was powered by big railroad ventures, like the networks run by Cornelius Vanderbilt, and the Central Pacific Railroad in California, which was led by a bunch called the “Big Four”—Charles Crocker, Mark Hopkins, Collis Huntington, and Leland Stanford, who also founded Stanford University.

Telegraph lines flanked the railroad tracks, and telephones started appearing in the late 1870s, unleashing instant business communications throughout the country (provided you could afford the long-distance phone charges!). Train tracks were switched from iron to steel, which handled heavier loads of cargo and mail. Farmers could now shop through a product catalog and order the latest tools and equipment for their family business. Food and consumer products crisscrossed the country.

The oil, steel, and copper industries took off, along with many others. Production of steel skyrocketed from under 2,000 tons in 1867 to over 7.2 million tons by 1897, which was more than Germany and Britain combined. Coal, iron, copper, and silver mines opened up across Appalachia and the Midwest and western states. Giant new industrial complexes set up supply chains that created businesses for countless entrepreneurs, some as small as the mom-and-pop sandwich-and-coffee stand parked outside the factory gate.

By the 1880s, America had become a vast, vibrant national market for entrepreneurs with ambition and vision. According to Yale University historian Naomi Lamoreaux, “The half-century or so following the Civil War was a period of extraordinarily rapid economic growth in the United States. Real gross domestic product (GDP) multiplied more than seven times between 1865 and 1920, and real per capita product more than doubled.” She added, “Americans have always admired entrepreneurs, but during the years 1865–1920 this attitude was more intense than at virtually any other time in U.S. history.” Railroads linked the coasts together, the West fully opened up for business and farming, prospectors rushed west in search of gold, inventors patented a blizzard of new products and technologies, and banks and investors cashed in on the fast-rising tide of entrepreneurship.

This was an age when American entrepreneurs rose to become giants who built empires that shaped the nation, and the world.

Of these giants, three super-tycoons, steel man Andrew Carnegie, banker J. P. Morgan, and oil magnate John D. Rockefeller, stood head and shoulders above the rest, and followed in the path of trailblazer Cornelius Vanderbilt and the transportation networks he pioneered. The three men were friends, enemies, schemers, collaborators, and competitors. Sometimes they were monopolists, and sometimes they created new industries from scratch. Some folks thought they were “robber barons” drunk with power and greed; other people thought they were champions of charity.

These three mega-entrepreneurs were among America’s greatest empire builders. They and their fellow entrepreneurs helped lead post–Civil War America into the modern era.

And one of them started off like many American entrepreneurs do—as a penniless immigrant.

He came to this country as a poor twelve-year-old immigrant from Scotland.

He rode the waves of three megatrends—telegraphy, railroads, and steel—to become the richest man on earth, and a founding father of American philanthropy.

Andrew Carnegie was the ultimate American immigrant success story. Though he stood just over five feet tall, he towered over American business history.

Born in 1835, the young Carnegie watched as his beloved father, a handloom weaver, got thrown out of work in Scotland by the new technology of steam-powered handlooms. His mother, a proud, dignified woman, was reduced to mending boots to scrape together enough money to feed and clothe the family, as his father couldn’t find a job. “I began to learn what poverty meant,” Carnegie recalled. “It was burnt into my heart that my father had to beg for work. And there came the resolve that I would cure that when I got to be a man.”

When the desperate Carnegie family immigrated in 1848 across the Atlantic to a slum in what was then the soot-choked, stinking industrial city of Pittsburgh, young Andrew worked twelve-hour days in a textile mill and as a boiler tender. It was hard work, but Carnegie felt proud. “I have made millions since,” Carnegie remembered. “But none of those millions gave me such happiness as my first week’s earnings.” He explained, “The hours hung heavily upon me, and in the work itself I took no pleasure. But the cloud had a silver lining, as it gave me the feeling that I was doing something for my world—our family.”

Like Carnegie, I know the feeling of spending twelve-hour days in extremely tough jobs, too. In my younger days, to make a buck before our family business took off, I put in time as a telemarketer, a camp counselor, a janitor, a handyman, and a worker in an ice cream plant, where most of the time, I literally had to work inside a freezer. Boy, did I hate that!

For Carnegie, everything changed when he got his first white-collar job as an office boy for what was then a cutting-edge, high-tech operation: a telegraph company. He was practically in a state of rapture. “There was scarcely a minute in which I could not learn something or find out how much there was to learn and how little I knew,” he later recalled. “I felt that my foot was upon the ladder and I was bound to climb.”

In those days, working at a telegraph office was as good as working for Google. Carnegie soaked up every bit of information he could. “As the steel pen embossed the dots and dashes of the Morse alphabet on a narrow strip of paper—an electric current moving the pen—the boy learned of international, national and local happenings,” wrote Carnegie biographer Peter Krass. “Most important, at age 14, Andy was riding the wave of a new technology and privy to much business correspondence passing through the office. He learned which businesses were buying, which were selling, which were growing and which were failing,” which was “all inside information that he eventually used to his benefit.”

At night, Carnegie memorized the names and addresses of key business leaders in Pittsburgh, so he could ingratiate himself with them. On the side, he sold news stories that came across the telegraph wires to the local papers. At sixteen, he was his family’s chief breadwinner.

Carnegie had a simple dream—of one day becoming an entrepreneur. His plan, he explained to his little brother, was to start a “great” business, one that was successful enough to enable their father and mother to “ride in their carriage.” He attended night school to study accounting and double-entry bookkeeping. He was promoted to a full-time telegraph operator, then took a job as a junior manager at the Pennsylvania Railroad, where he learned, in the words of one Carnegie biographer, “the management skills, the financial dealings and the political maneuvers to build an empire.”

In 1855, Tom Scott, Carnegie’s mentor at the Pennsylvania Railroad, loaned the young go-getter $500 to buy shares in a privately held express-delivery company. When the investment soon began paying him a dividend of $10 a month, or $270 in today’s money, Carnegie practically jumped for joy. “I shall remember that check as long as I live,” he wrote. “It gave me the first penny of revenue from capital, something that I had not worked for with the sweat of my brow.” He hollered out “Eureka!” and thought, Here’s the goose that lays the golden eggs. This was the start of Carnegie’s long career as an investor. With the support of his bosses at the railroad company, he invested in bridges, steel-reinforced rails, sleeper train cars, and oil prospecting.

In 1865, Carnegie left the Pennsylvania Railroad to strike out on his own as a full-time entrepreneur, working for no one but himself, focusing on an industry he knew quite well by now, one that was the lifeblood of America’s post–Civil War economic boom: iron and steel. His strategy was to master one business at a time, not to diversify. He decided, in his words, “to go entirely contrary to the adage not to put all one’s eggs in one basket. I determined that the proper policy was ‘to put all good eggs in one basket and then watch that basket.’” Carnegie explained, “I believe the true road to pre-eminent success in any line is to make yourself master in that line. I would concentrate upon the manufacture of iron and steel and be master in that.”

Carnegie took this idea of “vertical integration”—of laserlike focus on a single business—to an extreme, by owning all the steps of production and transportation from the final point of sale all the way back to the original source. Eventually, in the iron and steel business, he controlled a long chain of operations that connected the whole process from start to finish: iron ore mines, vessels that shipped iron ore through the Great Lakes, railroads, coke-burning ovens, and iron and steel plants. In the process, capitalizing on the post–Civil War construction and railroad boom, he dominated the steel industry in less than a generation.

In the 1870s, Carnegie led the industry switch from pig iron to higher-tech, stronger, low-cost steel, which was ideal for railroads, factories, and skyscrapers. “Andrew Carnegie was a brilliant cost analyst,” said David Hounshell, professor of technology and social change at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh. “He knew what were his labor costs, his capital costs and his materials costs, and he knew how to drive the costs down. This was a great advantage.” He was also a marketing genius—one time, to prove the strength of his product, he invited the press to watch a hired elephant lope across a bridge made with Carnegie steel. By creating the American steel industry, Carnegie spearheaded America’s march into the modern industrial age.

Carnegie was a great businessman, but he was not a saint. In fact, his tactics could be downright brutal. To squeeze maximum efficiency and profit out of his pollution-spewing plants, he always ran them at full capacity, and he ordered his workers to work twelve-hour shifts six days a week in hellishly hot blast-furnace conditions. Carnegie biographer David Nasaw wrote, “The installation of the 12-hour workday had a profound effect on the workforce, turning once proud artisans into animals, too debilitated by exhaustion to live like men.” Conditions at his plants were so grim that a visiting Carnegie friend said that “six months’ residence here would justify suicide.”

The worst episode of Carnegie’s career happened in 1892, when he took off for a Scotland vacation and left his partner, the union-busting industrialist Henry Clay Frick, in charge of his steel plants. A 143-day strike unfolded at Carnegie Steel’s plant in Homestead, Pennsylvania. Frick ordered in three hundred armed guards from the Pinkerton Detective Agency and a full-blown fracas ensued that turned into a pitched gun battle. A dozen people were killed. Carnegie wasn’t directly responsible for the bloodshed—he was in favor of unions—but he was blamed publicly for it. He pushed Frick out of the company. When Carnegie later reportedly sent Frick a note asking to renew their friendship, Frick replied, “Tell him I’ll see him in hell, where we are both going.” Later, Carnegie created a relief fund for his workers and their families, and became a pioneer for worker pensions.

In 1889, Carnegie championed a radical idea. You could call it “extreme philanthropy,” and it was an idea that Bill Gates, Warren Buffett, and other super-tycoons would echo a century later. In a magazine article dubbed “The Gospel of Wealth,” he argued that the rich have a moral obligation to give away almost all of their money. Not only should wealthy people contribute to the community, Carnegie declared, but all personal wealth, beyond the basic amount for one’s own family, should be considered as a trust fund to create economic opportunity for the less fortunate.

The wealthy person, Carnegie wrote, should “set an example of modest, unostentatious living, shunning display or extravagance; to provide moderately for the legitimate wants of those dependent upon him,” and then devote their fortune to “produce the most beneficial results for the community—the man of wealth thus becoming the mere agent and trustee for his poorer brethren, bringing to their service his superior wisdom, experience and ability to administer, doing for them better than they would or could do for themselves.” He felt that charity should not be focused on simply giving indiscriminately to the poor, which he feared would “encourage the slothful, the drunken, the unworthy,” but should instead be directed to institutions that can help the poor uplift themselves. People who died rich, Carnegie thought, were a disgrace. They should give away their money instead, all of it.

In 1900, Carnegie was getting ready to retire. He got a message from his fellow mega-entrepreneur, the financial mogul J. Pierpont Morgan, who was a latecomer to the steel business and finding it next to impossible to compete with Carnegie’s near monopoly. Morgan asked Carnegie to name his price for a full buyout of his steel business. Carnegie replied, $480 million. “Mr. Carnegie, I want to congratulate you on being the richest man in the world!” said Morgan to Carnegie when the deal was closing. Carnegie then asked Morgan if he should have asked for $100 million more instead. Morgan said if he had, he would have gotten it. Morgan turned the business into America’s first billion-dollar corporation, U.S. Steel.

Now it was time for Andrew Carnegie to do his greatest deed—to give away nearly his entire fortune, using what he called the “principles of scientific philanthropy,” which treated giving as a strategic investment to help people improve themselves.

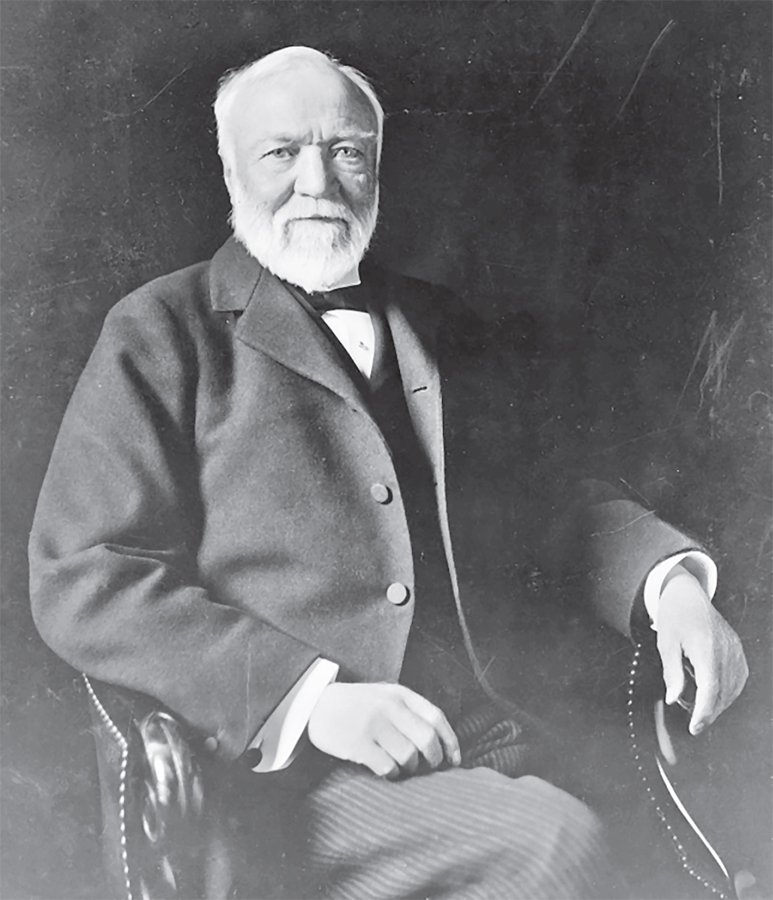

Man of Steel: Andrew Carnegie at the peak of his power. (Theodore C. Marceau, Library of Congress)

By 1910, the accrued interest on Carnegie’s fortune was accumulating so fast that he simply couldn’t give away money fast enough on his own, so he set up the Carnegie Corporation of New York as a philanthropic foundation to take over the process of screening, selecting, and investing in charities worthy of support.

Carnegie’s passion for charity gave birth to an amazing number of projects that made America a better place. His favorites were schools, museums, and libraries. Of one of his libraries, he said, “It’s the best kind of philanthropy I can think of.” His money created the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Carnegie Mellon University, the Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh, the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh, the Carnegie Institution for Science, the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, and more than three thousand Carnegie libraries in the United States and globally. When he died, Carnegie had a net worth of over $300 million.

How did he do it? By following a basic, brilliant business philosophy—innovate constantly, invest in the latest technology and equipment, be a low-cost producer, and maximize and retain profits to tide you over when times get tough and competitors stumble.

In my own career as an entrepreneur, I have found that much of the success of our business comes from these principles—innovating with new products and spin-offs, embracing the technologies of DVDs and the Internet, constantly looking for production efficiencies, and reorganizing our finances to maximize profits. I’ve learned some of these lessons the hard way!

Believe it or not, Andrew Carnegie was the godfather of PBS, Big Bird, and Elmo, too. In the 1960s the Carnegie Corporation of New York championed the creation of the national Public Broadcasting System and nurtured the creation of Sesame Street.

“Maybe with the giving away of his money,” speculated Carnegie biographer Joseph Wall, it helped him “justify what he had done to get that money.”

Carnegie spent his last eighteen years giving away nearly 90 percent of his fortune. After his death in 1919, most of what was left was given to charities.

Carnegie gave away more money than any other twentieth-century American, with the exception of one—a fellow by the name of John D. Rockefeller, whom we will meet in just a few pages.

Unlike Andrew Carnegie, John Pierpont Morgan was not a self-made man who went from rags to riches.

He was born, as they say, with a silver spoon in his mouth. He started his own company at age twenty-four as an extension of the family business, and he went on to become America’s greatest investment banker, a man who personally rescued the nation’s economy on three different occasions.

Born in 1837, Morgan was raised in the lap of luxury in Hartford, Connecticut, the son of a wealthy investment banker who did most of his business in London. Young Pierpont studied business math at prep school, then studied French, German, and art history in Europe. He went to work for his father at age twenty, then moved to New York City and opened J. Pierpont Morgan & Company in 1861 to act as the family’s Wall Street office, and in 1871 he started Drexel, Morgan with partner Anthony Drexel, setting up their office at what soon became the most famous address in American banking: Broad and Wall Street.

As the years passed and he got richer and richer, Morgan, who as a young man was handsome and broad-shouldered, became physically cursed with blotchy skin and a bloated, disfigured nose that was once described as looking like “a purple bulb.” It was, according to one historian, a nose “like an over-ripe pomegranate, a flaming, coruscating beak that could stop traffic at 50 paces, the kind of nose usually associated with a non-stop drinker of cheap booze.” In reality, the condition was known as rhinophyma, a condition that causes excess growth of sebaceous tissue. Even with all his money, there wasn’t anything Morgan could do about the deformity other than carefully stage his photos and portraits to minimize the startling effect, which must have been intimidating when experienced in person, especially across a conference table during a financial negotiation. He once said of his nose, “It is part of the American business structure.”

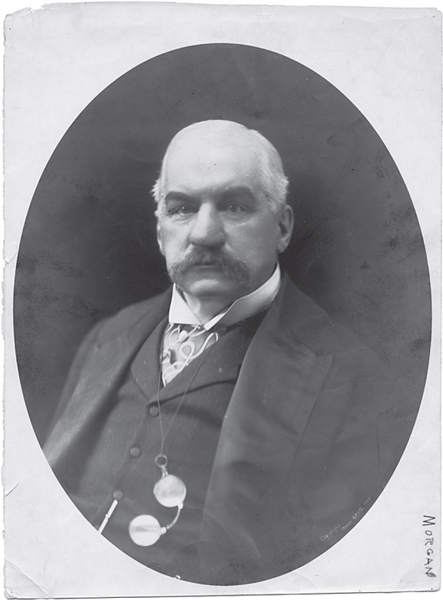

J. Pierpont Morgan. (New York Public Library)

By the 1870s and 1880s, Morgan was emerging as America’s top investment banker, juggling mergers, acquisitions, and consolidations with incredible skill and timing.

Morgan biographer Ron Chernow explained that “[d]uring the 1870s, Pierpont began to style himself as far more than a mere provider of money to companies. He wanted to be their lawyer, high priest and confidant. This wedding of certain companies to certain banks—relationship banking—would be a cardinal feature of private banking for the next century.” When he invested in a company, Morgan usually insisted on hands-on powers to stabilize and reorganize the company as he saw fit, so he could maximize returns. He applied the process, which came to be known as “Morganization,” to a network of railroad companies that by the early 1900s controlled nearly half of the nation’s rail lines. Some of Morgan’s business combinations were so huge that critics called them monopolies, or anticompetitive “trusts.”

Morgan was, in Chernow’s words, “America’s most powerful man.” “Pierpont differed from most of the Gilded Age robber barons in that their rapacity stemmed from pure greed or a lust for power while his included some strange admixture of idealism,” noted Chernow. “He was honest to a fault and had a clear-cut sense of right and wrong, so when he confronted an economy that offended his business propriety, it gave him a revolutionary zeal.” In 1892, J. P. Morgan helped launch General Electric Company, underwriting its first stock issue. He believed in the product, too—a decade earlier, he was the first New Yorker to have electricity put into his home. He also helped create industrial giants AT&T and International Harvester.

Not everything Morgan touched turned to gold—his shipping venture, the International Mercantile Marine, tanked after its showcase venture—a transatlantic ocean liner called the Titanic—hit an iceberg and sank to the bottom of the ocean during its 1912 maiden voyage, taking more than 1,500 passengers down with it.

Morgan was a devout Episcopalian, but unlike Andrew Carnegie, he had no passion for helping the poor and disadvantaged. He preferred to support the arts, and he collected paintings from Europe, Egyptian antiquities, and rare books, and delighted in throwing lavish parties on his private yacht, the Corsair. He cofounded the American Museum of Natural History and served as chairman of the board of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, to which he donated a fortune in artwork.

The opulent interior of the Morgan Library, which today houses many of J. Pierpont Morgan’s collections. (Library of Congress)

Despite being married, he was said to engage in a wide range of romantic entanglements, especially with famous actresses. He reportedly kept two older actresses in a London apartment, leading one art dealer to quip, “Morgan not only collects Old Masters, he also collects old mistresses.”

For nearly twenty years, from 1894 to 1913, J. P. Morgan acted like a one-man financial SWAT team, swooping in to do spectacular deals and rescue entire governments from economic collapse. At the same time, naturally, his company leveraged the emergencies to make huge profits.

In 1894, America’s gold system was in danger. Gold reserves had dipped to a scant $9 million, and Morgan warned President Grover Cleveland that $12 million in drafts were about to be presented. According to Morgan biographer Daniel Alef, “In the absence of an income tax, the government’s ability to increase its reserves was dependent on its ability to borrow money. But because of a two-year economic collapse, the nation’s credit worthiness was essentially nil. Pierpont proposed a daring solution: He would gather $62 million in gold in exchange for $65 million in thirty-year government bonds redeemable in gold or silver and make arrangements that would avoid a dangerous gold outflow happening again.” By briefly guiding the flow of gold in and out of the country and rebuilding America’s gold stockpile, Morgan stabilized the system.

In 1902, Morgan cooperated with his sometime enemy President Theodore Roosevelt to help settle a coal strike. In 1904, Morgan helped finance the building of the Panama Canal, the biggest real estate transaction in history. In 1907, Wall Street fell into a panic, causing a run on banks. Without a central bank, the federal government turned to J. Pierpont Morgan for salvation.

On Thursday, October 24, 1907, panic spread on Wall Street and state banks and trust companies teetered toward collapse as customers pulled out millions of dollars in cash. That day, J. P. Morgan began an astonishing one-man rescue operation of the American economy.

To stabilize the nation’s money supply, Morgan directed the secretary of the Treasury to deposit tens of millions of dollars to pass through to banks and trusts carefully hand-picked by Morgan. He announced to reporters that “if people will keep their money in the banks, everything will be all right.” When people successfully withdrew amounts from one key trust company without any problems, the panic at that institution eased.

But the crisis continued—that day, the president of the New York Stock Exchange appeared in Morgan’s office and declared that the exchange had to be shut down since its brokers had run out of money from banks to finance margin accounts. Morgan ordered that the exchange stay open, and in five minutes flat he worked out a deal with the nation’s leading bankers to pump a critical $27 million into the exchange to keep it running.

That night, Morgan invited the top bankers in the United States to his opulent mansion on New York’s Madison Avenue, installed them in his plush library, and encouraged them to find a solution as he sometimes stayed outside the room flipping playing cards, enjoying a game of solitaire. Together, they all patched together more targeted emergency cash injections to prop up vulnerable banks and keep money flowing into the stock exchange.

Morgan issued a veiled threat—any stockbroker who chose to profit from the panic would be “properly attended to.” Nobody knew exactly what he meant, and nobody wanted to find out, either. The next day, Friday, came and went without a bank failure, and the pace of withdrawals eased.

By now, J. P. Morgan had choreographed the responses of the federal government, the banks, and the stock market, so there was one more weapon to unleash—the power of God. He summoned the senior religious clergy of New York City to his mansion and told them to preach optimistic sermons from the pulpit on Sunday morning. They did, and the following week, the crisis eased and the nation avoided falling into a severe depression.

It took Morgan, a financial entrepreneur of incredible energy and genius, barely ten days to save the American economy.

When Morgan pulled off this miracle, financier Bernard Baruch called him “the greatest financial genius this country has ever known.” By now, some were calling him “the Napoleon of Wall Street.” His biographer Lewis Corey called the 1907 rescue “Morgan’s supreme moment, the final measure of power and its ecstasy.” The same year, Morgan rescued the city of New York from defaulting on its debt by talking other bankers into purchasing $30 million worth of municipal bonds. “With his financial power,” wrote Pittsburgh journalist Donald Miller, “Morgan not only deflected at least three national panics, saving Americans from stock-market losses, but also virtually single-handedly steadied the course of the country’s financial development before government agencies grew up to that task.”

Like Andrew Carnegie, J. P. Morgan had his share of enemies, too, including a Republican senator who called him “a beefy, red-faced, thick-necked financial bully, drunk with wealth and power, [who] bawls his orders to stock markets, directors, courts, governments and nations.” But biographer Jean Strouse noted, “Even some of Morgan’s critics said he was a builder and conservator, not a wrecker, liar or cheat.” She credited him with thriving “in cycles of expansion and contraction, through panics, depressions, competitive price wars, speculative gambles and government defaults.” When a “Morganization” was successful, she wrote, “stock prices rose; when a combination [merger] failed, all his financial and political efforts could not keep share prices from falling.” Morgan thought that necessity “had drafted him to do what he could to police the markets and keep the U.S. economy on track, but in the end no one could control money.”

Morgan could be cold-blooded when he felt it necessary. Take, for example, his treatment of the great genius, inventor, and fellow entrepreneur Thomas Edison, who, over the course of his lifetime, patented 1,093 inventions and pioneered recorded sound, the alkaline battery, the motion picture camera, the stock ticker, improved X-ray machines and telegraph equipment, the modern R&D lab, the lightbulb, and sustained electric light.

The Wizard of Wall Street: J. P. Morgan at a 1917 war bonds rally in New York. In an odd twist, Morgan’s famous nose, described by witnesses as horribly ugly, seems completely handsome in this photo, which must have been taken on a “good nose day” for the master financier. (Library of Congress)

By the late 1880s, Edison had opened up 121 Edison central power stations in the United States, and J. P. Morgan owned a majority of the shares of Edison’s firm, the Edison General Electric Company. In 1892, without warning Edison, Morgan abruptly merged Edison’s company with another, more profitable company, demoted Edison, and then pulled Edison’s name off the company, now known simply as General Electric.

Edison’s feelings were hurt, but he continued to thrive. So did one of the engineers in his laboratory, a brilliant young fellow named Henry Ford. Edison liked Ford’s idea of a new automobile and let Ford use his warehouse to build two experimental prototypes. Eventually, as a full-time entrepreneur on his own, Ford unleashed the power of mass production and the moving assembly line, creating the affordable Model T “car for the masses” and the Ford Motor Company, which achieved global reach and power.

As for Morgan, in 1913, just before he died at age seventy-five, he championed the creation of the Federal Reserve, which strengthened America’s banking system. The idea was to eliminate the need for the kind of private bailouts he’d conducted. On the morning of his funeral, the New York Stock Exchange was shut down in his honor, a move usually reserved for heads of state. At the time of his death, he controlled ten railroads, five industrial companies, including U.S. Steel, and a portfolio of insurance companies and banks. His personal wealth was estimated at anywhere from $1 billion to $40 billion in today’s dollars.

It was a lot of money, but one fellow entrepreneur and super-tycoon wasn’t too impressed.

Upon hearing the figures, this man reportedly quipped, probably half in jest, “And to think he wasn’t even a rich man.”

Only one person could get away with a crack like that.

His name was John D. Rockefeller. He was the most successful American entrepreneur of all time—and the richest man in modern history.

If you measure greatness in business by the amount of money you make, then John D. Rockefeller was the greatest entrepreneur in American history.

And if you measure greatness in life by the amount of money you give to others, then Rockefeller was one of the greatest philanthropists who ever lived.

Which is not a bad record for a slightly built, working-class, upstate New York boy, born in 1839, who grew up in a family that experienced extreme economic instability, and whose often-absent father, William, was a traveling salesman who was widely believed to be a con artist, or “flimflam man.” William did find time to teach his offspring some basic business lessons, including one he explained this way: “I cheat my boys every chance I get. I want to make ’em sharp.” John’s long-suffering mother, by contrast, taught young Rockefeller the Christian virtues of thrift, charity, hard work, and self-control. The family moved to Cleveland, Ohio, to escape the shame of rumors that connected the father to alleged sexual impropriety.

As a boy, John D. Rockefeller attended Baptist church services with his devout mother and his siblings. One day, the minister encouraged his congregation to make as much money as possible—and give away as much money as possible. “It was at this moment,” Rockefeller recalled, “that the financial plan of my life was formed.” Eventually, Rockefeller would live out the biblical concept detailed in Luke 6:38, “Give, and it will be given to you. A good measure, pressed down, shaken together and running over, will be poured into your lap. For with the measure you use, it will be measured to you.” Later, looking back on the incredible fortune he made, Rockefeller declared simply, “God gave me the money.”

Rockefeller was fascinated with money from an early age. As a boy he bought candy in bulk and sold it at a profit to his siblings. As soon as he turned sixteen, Rockefeller started hustling for a steady income, taking an accounting course (just like Andrew Carnegie) and a bookkeeping job at a small produce shipping company. He worked very hard and loved learning, he remembered, “all the methods and systems of the office.” His first day of work was September 26, 1855, a date he celebrated for the rest of his life. “All my future seemed to hinge on that day,” he remembered. “I often tremble when I ask myself the question: ‘What if I had not got the job?’” He began the lifelong habit of recording all his expenses.

The young Rockefeller soaked up the world of small business like a sponge, earning the de facto equivalent of an MBA in real-world experience by the time he was eighteen years old. “To begin with, my work was done in the office of the firm itself,” he remembered. “I was almost always present when they talked of their affairs, laid out their plans, and decided upon a course of action. I thus had an advantage over other boys of my age, who were quicker and who could figure and write better than I. The firm conducted a business with so many ramifications that this education was quite extensive. They owned dwelling-houses, warehouses, and buildings which were rented for offices and a variety of uses, and I had to collect the rents. They shipped by rail, canal, and lake. There were many different kinds of negotiations and transactions going on, and with all these I was in close touch.”

From the start, Rockefeller donated 6 percent of his small salary to charity, and was soon tithing to his Baptist church. He declared that his life’s ambition was to earn $100,000 and live to be one hundred years old. He achieved his first goal very quickly, and he missed the second by less than three years.

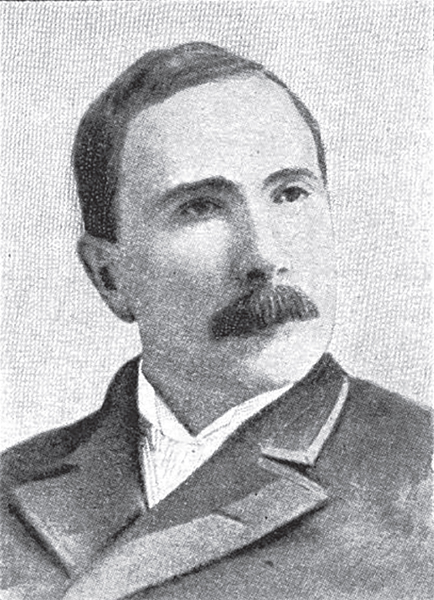

A young John D. Rockefeller. (New York Public Library)

In 1859, at the tender age of eighteen, Rockefeller borrowed $1,000 from his father and, with a partner, started his own company and became a full-time entrepreneur, specializing in trading produce, meat, and grain. “He developed a reputation among bankers for being a devout Christian who was absolutely honest,” wrote journalist Scott Smith, “giving his firm an advantage in lining up support.”

Rockefeller and his partner made big money on government contracts during the American Civil War. By 1862, their profits totaled some $400,000 in today’s currency—but Rockefeller always kept his eye open for new opportunities. “He thought large and lived by the dictum ‘never be afraid to give up the good to go for the great,’” noted historian June McCash. “He always had a plan and a clear-sighted goal.” At the age of twenty-one, Rockefeller was a prominent businessman in Cleveland. “Business came in upon us so fast that we hardly knew how to take care of it,” he later marveled.

In 1864, at age twenty-five, Rockefeller and his partners made one of the best investments in business history: they acquired control of Cleveland’s biggest oil refinery, which processed five hundred barrels of crude a day, twice the volume of its closest competitor. According to journalist Scott Smith, “By that time, whale oil had become too expensive for most Americans to use for lighting, so they had turned to tallow, lard, cottonseed oil, coal oil, and the newest—kerosene, which was refined from the only known petroleum fields in the world, in northwest Pennsylvania. Pitched the opportunity to build a refinery in Cleveland, with its easy access to transport by rivers and lakes, Rockefeller seized it.”

Rockefeller studied the brand-new oil market carefully. It was just five years since oil was discovered in Pennsylvania, which was pretty close to Rockefeller’s home base of Cleveland. He shrewdly predicted that the big money was to be made in the consistent, steady business of refining and shipping, not the speculative business of drilling, where you could lose a lot of money punching dry holes in the ground. “Never one to do things halfway, he plunged headlong into the business,” wrote biographer Ron Chernow. “There was humility in his eagerness to learn. Devoid of superior airs, he was often seen at 6:30 a.m. going into the cooper shop to roll out barrels. Since a residue of sulfuric acid remained after refining, he drew up plans to convert it to fertilizer, the first of many worthwhile and extremely profitable by-products from waste materials.”

It was the perfect time to jump into the oil business. The American economy was leaping westward along the newly built railroad tracks, and industry was about to take off on an oil-powered boom.

Rockefeller later told of the excitement he felt in being a young, hands-on entrepreneur, and an aggressive competitor in a cutthroat industry: “I shall never forget how hungry I was in those days. I ran up and down the tops of freight cars, I hurried up the boys.” Rockefeller and his partners expanded rapidly. “We were being confronted with fresh emergencies constantly,” he remembered. “A new oil field would be discovered, tanks for storage had to be built almost overnight, and this was going on when old fields were being exhausted, so we were therefore often under the double strain of losing the facilities in one place where we were fully equipped, and having to build up a plant for storing and transporting in a new field where we were totally unprepared. These are some of the things which make the whole oil trade a perilous one, but we had with us a group of courageous men who recognized the great principle that a business cannot be a great success that does not fully and efficiently accept and take advantage of its opportunities.”

In 1867 Rockefeller recapitalized his company with a $100,000 loan from Stephen Harkness, who became a silent partner in the firm and required that his relative Henry Flagler also be brought in as a partner to represent his interests. A few years earlier, Flagler had gone broke in the salt business, but he became a perfect partner for Rockefeller and later became a founding partner and one-sixth owner of Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company. Later, when he cashed out, Flagler had made enough money on his Standard Oil stock that he pretty much created the modern state of Florida, turning it, in the words of historian John Steele Gordon, “from a semi-tropical wilderness into a tourist mecca and agricultural powerhouse.”

On December 18, 1867, a week before Christmas, Rockefeller’s luggage was loaded onto the eastbound New York Express at Cleveland’s Union Terminal train station. The train pulled away at 6:40 that morning, but by chance, Rockefeller wasn’t on it. He was a few minutes late and just missed the train. At 3:11 P.M., east of the tiny New York State community of Angola, the two last cars of the speeding train derailed as it crossed the bridge over Big Sister Creek, sending one coach car plummeting down the gorge to the creek bed forty feet below. Ignited by the wooden car’s heating stoves and kerosene lanterns, it exploded into an inferno, trapping and killing nearly fifty people inside, many of them burned alive. Rockefeller, who took a later train, sent a telegram back to his wife in Cleveland: “THANK GOD I AM UNHARMED.” The event became known as the “Angola Horror,” and Rockefeller barely escaped it, just as Cornelius Vanderbilt narrowly escaped a similar railroad disaster decades earlier.

In 1868, Rockefeller secretly cut a deal with the Lake Shore Railway that guaranteed sixty carloads of oil per day in exchange for reducing the freight charge from $2.40 per barrel to $1.65. Both sides kept the deal secret, and Rockefeller gained a huge competitive advantage. He struck similar deals with other railroads that increased costs for his competitors. This type of pricing favoritism, or conspiracy, was outlawed by the federal government twenty years later when it declared railroads to be common carriers for public benefit, but for now, Rockefeller had a wide-open field to secretly cash in on the economies of scale.

As his entrepreneurial venture thrived, Rockefeller bought up some competitors and drove others out of business who simply couldn’t compete with him. In 1870, Rockefeller and his partners formed a joint-stock business, Standard Oil Company (Ohio), which he considered a cooperative alliance and critics attacked as a competition-killing cartel, or monopoly. Soon Standard Oil was being publicly attacked as “the most cruel, impudent, pitiless, and grasping monopoly that ever fastened upon a country” by America’s largest newspaper, the New York World. Biographer Ron Chernow reported that “Rockefeller and other industrial captains conspired to kill competitive capitalism in favor of a new monopoly capitalism.”

In what became known as “The Cleveland Massacre of 1872,” Rockefeller seized control of twenty-two of his twenty-six local competitors. His terms were often generous, but there was an implicit risk for those who refused to play ball—one of Rockefeller’s targets lamented that “if we did not sell out we should be crushed out.” Historian Charles Morris noted that “Rockefeller may have been unique among oil executives for his understanding of distribution, pursuing tightly integrated marketing and distribution operations from the earliest days, rapidly moving from contractual relationships to mergers.” Biographer Chernow wrote that the year 1872 “revealed both his finest and most problematic qualities: his visionary leadership, courageous persistence and capacity to think in strategic terms, but also his lust for domination, self-righteousness and contempt for those who made the mistake of standing in his way.”

In 1879, Rockefeller’s Standard Oil was indicted by the state of Pennsylvania on charges of running a monopoly, and other states brought suits as well. For Rockefeller, who was, at the same time, borrowing heavily from banks and reinvesting his profits to keep growing, the strain was tremendous. As he labored to create a “national trust,” or a vast integrated business empire of pumping, shipping, barrel-making, and warehousing, and plants for manufacturing oil by-products, pipelines, and international wholesaling, he couldn’t sleep, fell deep into debt, and constantly worried. “All the fortune that I have made has not served to compensate me for the anxiety of that period,” he said.

By 1879, Rockefeller, still a young man at forty, controlled nearly 90 percent of America’s oil industry, with 100,000 employees, 20,000 oil wells, 5,000 railroad tank cars, 4,000 miles of pipeline, and a booming overseas business. “By the early 1890s, Standard Oil had achieved virtually complete vertical and horizontal integration of the American petroleum industry—something unusual in American business,” observed historian Robert Cherny. “Standard’s monopoly proved to be short-lived, however. With the discovery of new oil fields in Texas and elsewhere, new companies tapped those fields and quickly followed the path of vertical integration.”

Rockefeller had created the world’s first great modern multinational corporation. He moved his business and family to New York City and often took the subway to work, along with regular folks. He eventually built a country retreat in Westchester that was so palatial that one visitor called it “the kind of place that God would have built if only he’d had the money.” In 1901, fellow tycoon J. P. Morgan offered Rockefeller and his son spots on the board of U.S. Steel.

Then, at the turn of the twentieth century, at the time his business was going through the roof with the emergence of an automobile industry hungry for Standard Oil’s gasoline products, Rockefeller surprised everyone. He stepped away from the stresses and strains of day-to-day management of his empire, turned things over to his partners and his son and designated heir apparent John D. Rockefeller, Jr., and devoted much of his time to giving his money away, just as he’d vowed to do as a teenager. He retained the title of president and still had major influence on the company, but was semiretired from business and now a full-time philanthropist.

For years, Rockefeller had already been donating huge sums to charity. By the 1880s, he was receiving thousands of appeals for money every month, and he discussed the letters with his family around the breakfast table. “Four-fifths of these letters,” Rockefeller remembered, were “requests of money for personal use, with no other title to consideration than that the writer would be gratified to have it.” He started out by supporting the Baptist Church and education for African Americans.

Rockefeller discovered that the stresses of “do-it-yourself” charity on a meaningful scale could be just as bad as those of running a giant business. “About the year 1890 I was still following the haphazard fashion of giving here and there as appeals presented themselves. I investigated as I could, and worked myself almost to a nervous breakdown,” Rockefeller explained in his 1909 memoir. “There was then forced upon me the necessity to organize and plan this department of our daily tasks on as distinct lines of progress as we did with our business affairs.”

Rockefeller hired a Baptist preacher to advise him on his donations. The preacher said that Rockefeller’s ever-increasing fortune was like “an avalanche,” and warned him, “You must keep up with it! You must distribute it faster than it grows! If you do not, it will crush you and your children and your children’s children!” Rockefeller agreed, but also worried about the dangers of charity if it was not managed properly. “It is a great problem,” he said, “to learn how to give without weakening the moral backbone of the beneficiary.” But if people “can be educated to help themselves,” he reasoned, “we strike at the root of many of the evils of the world.” He concluded, “The only thing which is of lasting benefit to a man is that which he does for himself. Money which comes to him without effort on his part is seldom a benefit and often a curse.” Slowly and carefully, Rockefeller hired experts who helped him to become a philanthropist on a scale never before seen in history, a noble calling that occupied most of the last forty years of his life.

During his life and in the decades that followed his death, Rockefeller-funded projects made huge strides toward eliminating hookworm disease, malaria, scarlet fever, tuberculosis, and typhus, and funded research that led to the yellow fever and cerebrospinal meningitis vaccines. Rockefeller founded the University of Chicago, yet insisted that his name appear nowhere on the campus. He said the school was “the best investment I ever made.” He supported the Baptist Church in establishing Atlanta’s Spelman College, the oldest college historically for African American women, which has educated ambassadors, business leaders, and Pulitzer Prize winners. He named the school after his wife.

American colossus: John D. Rockefeller, the greatest entrepreneur and philanthropist in American history and the richest man in modern history (second from right), inspects “the best investment I ever made,” the University of Chicago, on its tenth anniversary in 1901. (University of Chicago)

Rockefeller founded schools of public health and hygiene at Johns Hopkins University and Harvard. He founded Rockefeller University in New York, a world-class scientific and medical institution. He introduced China to modern medical practices. His funds helped alleviate poverty in the South, provided education to hundreds of thousands of African Americans, and boosted medical and scientific research around the world.

In 1902, Rockefeller created a “General Education Board” that supported high schools, colleges, and universities around the nation. For one of the seats on his board of directors, Rockefeller chose Andrew Carnegie, with whom he had skirmished the previous decade when Rockefeller expanded into the iron ore business. The following decade, he started the Rockefeller Foundation “to promote the well-being of mankind throughout the world,” and thanks to its support of the “Green Revolution,” agriculture in the developing world was improved so dramatically that as many as one billion lives were saved. “The best philanthropy,” Rockefeller once wrote, “is constantly in search of finalities—a search for a cause, an attempt to cure evils at their source.”

From 1902 to 1904, Rockefeller was flat-out pummeled in the media when crusading journalist Ida Tarbell, whose oil businessman father had been put out of business by Rockefeller in the 1870s, wrote a number of devastating articles about Rockefeller in McClure’s, an influential national magazine. The articles revealed Rockefeller’s hardball business tactics in great detail, and worse, they revealed the scandals of his father. Also in 1904, President Theodore Roosevelt, an outspoken critic of Rockefeller and monopolies, declared his intention to destroy Standard Oil. For a time, Rockefeller was the most hated man in America, the subject of countless death threats that led him to sleep with a loaded revolver.

In 1911, after court cases that dragged on for ten years, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that parent company Standard Oil Company of New Jersey had engaged in illegal monopoly practices and was in violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act. The court ordered that the trust be broken up within six months.

The action had the incredible, unintended consequence of enriching John D. Rockefeller even further, as his stock in the new spin-off companies wound up being much more valuable than in the original single company. Rockefeller became the wealthiest person in American history, the country’s first billionaire. By some estimates, Rockefeller’s net worth peaked at nearly 2 percent of the United States economy—equal to around $300 billion in today’s dollars, or some three times the net worth of Bill Gates.

Think about it for a moment. That’s nearly a third of a trillion dollars!

Though Rockefeller succeeded in charitably investing and giving away much of this money, he boasts a family tree that is impressive in its own right. His grandson Nelson Rockefeller became a four-term governor of New York State, a champion of building the new World Trade Center in New York City in the early 1970s, and president of Rockefeller Center, the sprawling, landmark building complex erected by the family in midtown Manhattan. He served as vice president of the United States under President Gerald R. Ford but was then dumped from the 1976 ticket for being too liberal, and he failed in his lifetime ambition to become president. Nelson’s brother David became CEO of Chase Manhattan Bank and for decades was arguably the most powerful banker in the world. Another brother, Winthrop Rockefeller, was elected the first Republican governor of Arkansas since Reconstruction. John D.’s great-grandson, John Davison Rockefeller IV, served as U.S. senator from West Virginia from 1985 to 2015.

Rockefeller’s legacies continue to this day—more than one hundred years after Standard Oil was dissolved by the government, a number of its spin-off companies, like ExxonMobil, Chevron, ConocoPhillips, and Amoco, a division of BP, rank among the world’s biggest corporations. Rockefeller descendants have served as patrons of the arts, education, conservation, and a myriad of social causes and charities, and the Rockefeller Foundation continues today as a global philanthropic powerhouse.

John D. Rockefeller was by any measure the greatest philanthropist in history so far. Like Andrew Carnegie, Rockefeller discovered, to a scale rarely achieved by others, that the reason God put him on earth was, in the end, quite simple—to help his fellow human beings.

In Rockefeller’s case, it turns out he had a secret weapon. It was an advantage that many successful entrepreneurs have had—his spouse.

In 1864, Rockefeller married Laura Celestia Spelman, with whom he had four daughters and one son. She stayed with him for the rest of his life and all its tumult and glory.

“Her judgment was always better than mine,” said Rockefeller. “Without her keen advice, I would be a poor man.”

The same thing is perfectly true in my own life—without the business advice, encouragement, constructive criticism, inspiration, and love of my own wife, I would have accomplished very little in life.