Entrepreneurship has no age or time limits . . . it thrives on hope and inspiration. Those who choose to participate can only make the world a better place.

—Debbi Fields, founder of Mrs. Fields Cookies

If you’re ever in need of some inspiration, just think of the American entrepreneur.

And if you ever want a little extra inspiration, think of the millions of women and minority entrepreneurs who have helped build our nation over the last 250 years.

It’s tough enough being an entrepreneur. It’s all on you. You take the risk, you meet the payroll, you sweat all the details, you stay up at night worrying about your numbers and your customers. Success or failure is in your hands.

But for many decades our American women and minority entrepreneurs had to face not only the usual hurdles of business, but often a shortage of connections and credit and start-up capital, and sometimes even downright hostility from some parts of our government and society.

There’s one story that perfectly captures the grit, determination, and flat-out courage shown by countless women and minority entrepreneurs who have graced the pages of American history—the story of Madam C. J. Walker, the first self-made black female millionaire, and a pioneer in the cosmetics industry.

She was a strong, churchgoing, Louisiana-born woman, which makes me like her even more, as I married such a woman myself!

Madam Walker was born under the name Sarah Breedlove in 1867 in a cabin on the Burney plantation in Delta, Louisiana, a small community that’s about an hour-and-a-half drive from my house. Four years before she was born, the Burney plantation was a staging area for a turning point of the Civil War, General Ulysses S. Grant’s siege of Vicksburg, Mississippi. Walker grew up in a family of sharecroppers, in the midst of abject poverty, drudgery, and misery.

Walker’s parents were former slaves, and she was the first of her family to be born into freedom. She was orphaned at age seven. She moved in with a sister and her sister’s abusive husband, a situation she resolved to escape. “I married at the age of 14 in order to get a home of my own,” Walker later explained. Six years later, Walker’s own husband vanished from the scene. She was a mother at seventeen, and now at twenty she was a single mother with a little girl to take care of. To put food on the table, she worked as a laundress, scrubbing white people’s clothes on a metal washboard.

In 1889, Walker joined legions of other black migrants heading north to seek new opportunities, and she moved to St. Louis, where her four brothers were barbers. She continued being a washerwoman, but when she joined the local African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) church, she was inspired by the many high-achieving African professionals she met there, including teachers, lawyers, and doctors. “That’s when she began to envision herself as something other than an uneducated washerwoman,” said A’Lelia Bundles, Walker’s great-great-granddaughter, who has done extensive research into Walker’s sometimes mysterious past. She plunged into civic affairs and volunteer work, attended night school, and resolved to improve life for herself and her daughter. “I was at my washtubs one morning with a heavy wash before me,” Walker recalled. “As I bent over the washboard, I said to myself, ‘What are you going to do when you grow old and your back gets stiff?’”

Walker moved to Denver, Pittsburgh, and Indianapolis, had a failed second marriage, and, as fate would have it, saw her hair start falling out. It may have been stress, or bad nutrition, or it may have been the result of the widespread poor hair hygiene of the time. Many people, especially poor folks, didn’t wash their hair more than once a month or so.

There are two versions of what happened next. First, there is Walker’s version, in which her inspiration comes from a near-biblical vision. In a 1917 interview, she explained that she prayed to God for a miracle. “He answered my prayer,” she reported. “For one night I had a dream, and in that dream a big black man appeared to me and told me what to mix for my hair. Some of the remedy was from Africa, but I sent for it, mixed it, put it on my scalp and in a few weeks my hair was coming in faster than it had ever fallen out.” She shared the elixir with friends, who were amazed at its almost magical power to heal and grow hair. Then she began bottling and selling it, and an entrepreneurial empire was born. The truth, however, was a bit more complicated. In St. Louis and Denver, it turns out, she worked as a sales agent for African American cosmetics entrepreneur Annie Pope-Turnbo, selling, among other things, hair products.

Walker changed her name from Sarah Breedlove to the regal-sounding “Madam C. J. Walker,” in honor of her third husband, and in 1906 started her own line of products, including the top-selling “Madam Walker’s Wonderful Hair Grower,” and a hair-straightening product that included coconut oil, beeswax, copper sulfate, sulfur, and perfume. The booming sales of this product may have resulted not so much from any magic powers of its formula but rather from the fact that people started washing their hair more often as hygiene and nutrition were improving at the turn of the twentieth century. The potion’s sulfur may have helped heal scalp problems, too.

Blessed with a dazzling personality and a spellbinding sales pitch, Madam Walker started off selling her products door-to-door in Denver’s black neighborhoods, then moved to Indianapolis and opened up a manufacturing plant. She held product demonstrations by massaging customers’ scalps, pampering them, and making them feel beautiful. Walker hired a strong team of thousands of African American female door-to-door sales agents who became famous for their white blouses, black skirts, and leather satchels and were called “Walker Agents.” Money started flowing in by the bucketload.

This was grassroots, direct-to-consumer marketing, and Walker and her agents had a wide-open market, as few people had capitalized on this niche before in a big way. White cosmetics firms couldn’t have cared less about black business; they didn’t know there was much business to begin with. “Madam Walker fit into a whole pattern of women selling products in localities,” explained Kathy Peiss, a history professor at the University of Pennsylvania. “But what was interesting about Walker was how successful she was in building a national company with very high levels of sales. There were many, many women entrepreneurs, but most of them never made it, and she did.”

Starting in 1906, Walker ran newspaper ads featuring images of her own luxuriant hair, and before-and-after-treatment shots. She hit the roads through the American South, working with black churches and civic groups, staging demonstrations and classes, signing up sales agents and customers. Within just a few years, her sales force numbered in the thousands, and she was raking in a huge annual income unmatched by all but the most successful white businesspeople.

Walker expanded her business to the Caribbean and Central America, and pioneered business models later used by cosmetics giants like Avon, Helena Rubinstein, Mary Kay, and Elizabeth Arden, including door-to-door sales, product demonstrations, direct marketing, and money-back guarantees. In 1917, she staged one of the first national meetings of businesswomen in America: the Madam C. J. Walker Hair Culturists Union of America convention in Philadelphia.

Madam C. J. Walker, daughter of slaves, who created a legendary beauty products empire. (Scurlock Studio, Smithsonian Institution)

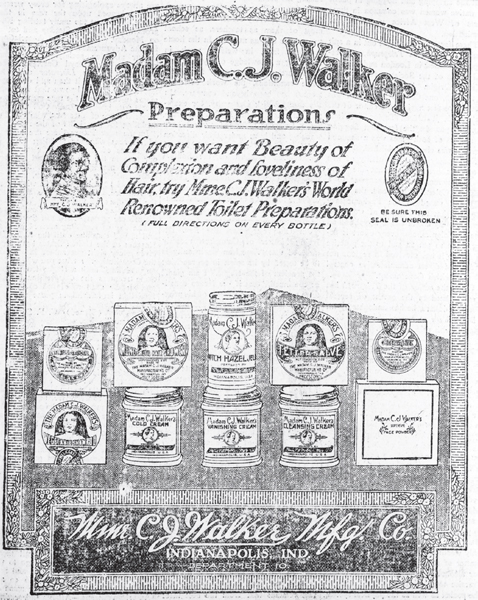

An early advertisement for Walker’s products. (Library of Congress)

In 1913, Madam Walker moved to New York and bought and renovated two combined old-style brownstones on West 136th Street, as she explained, “without regard to cost but with considerable regard for good taste.” Her new home featured scalloped pale gray chiffon curtains that flanked stylized Venetian windows, French doors that opened to a downstairs hair salon, Doric columns that marked the entrance to the upstairs living quarters, plus an intricately carved fireplace and English wall tapestries.

Walker also built a spectacular $250,000 three-story stucco Italian Renaissance–style suburban mansion, which she called Villa Lewaro, on a 20,000-square-foot estate in Irvington-on-Hudson, just a few miles down the road from John D. Rockefeller’s estate, complete with swimming pool, high ceilings, and marble floors. She explained that the purpose of the mansion was not conspicuous consumption but inspiration: “I am building this home so that I can show young black boys and girls all of their possibilities.”

Walker and her daughter A’Lelia became the toasts of black New York, and staged parties and literary salons attended by Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, dancer Isadora Duncan, and Italian tenor Enrico Caruso. In 1917, Walker traveled to Washington, DC, to present an antilynching petition to the White House. That year, she told a reporter, “I am not a millionaire, but hope to be some day, not because of the money but because I could do so much more to help my race.”

Sadly, Walker only got to live in her fantastic estate for a year before she died of kidney failure in 1919 at the age of fifty-one. Just before Walker died, her doctor heard her say, “I want to live to help my race.” That she did, and much more.

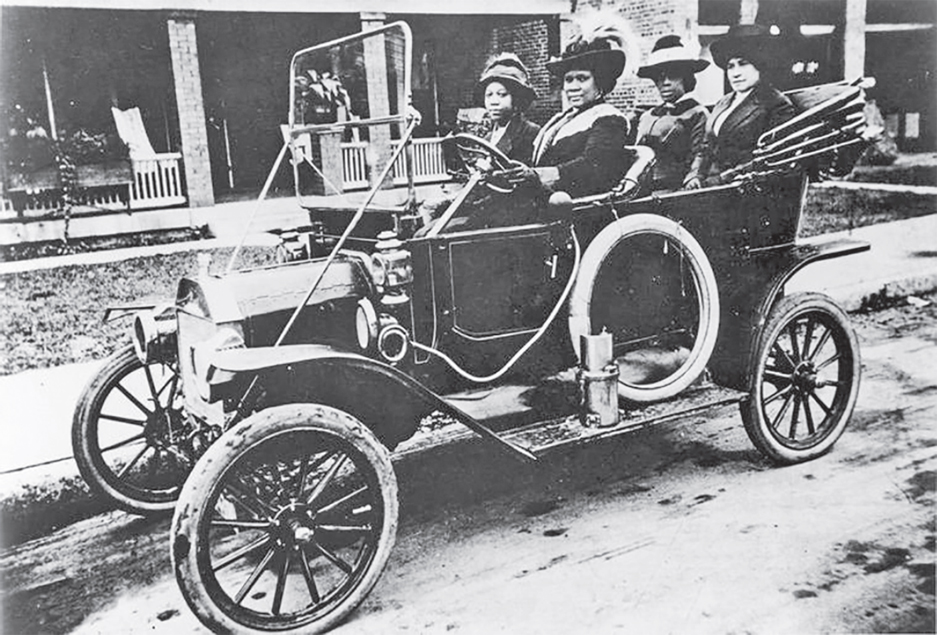

Madam C. J. Walker driving her niece and two company employees in 1911. (New York Public Library)

The great sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois eulogized Madam Walker this way: “It is given to few persons to transform a people in a generation. Yet this was done by the late Madame C. J. Walker,” who “revolutionized the personal habits and appearance of millions of human beings.”

“I am a woman who came from the cotton fields of the South,” said Walker in a speech to the National Negro Business League convention a few years before her death. “From there I was promoted to the washtub. From there I was promoted to the cook kitchen. And from there I promoted myself into the business of manufacturing.” She announced proudly, “I have built my own factory on my own ground.”

What was Madam Walker’s formula for success? In short, being proactive. “I got my start by giving myself a start,” she said. She explained, “Don’t sit around waiting for opportunities. You have to get up and make them.” Another time, she said, “There is no royal flower-strewn path to success. And if there is, I have not found it, for if I have accomplished anything in life, it is because I have been willing to work hard.”

At the same time that Madam C. J. Walker was achieving her destiny, a black man was writing his own incredible rags-to-riches story of American entrepreneurship in the great state of North Carolina.

John Merrick was born into slavery in 1859, and after emancipation he went to work at a young age as a brick mason to support his parents and siblings. When construction work slowed down, he trained as an apprentice barber. He saw barbershops as a thriving business with a strong future, so at age twenty he went to work in a barbershop in Raleigh as a shoeshiner. In 1880, when a friend opened a shop, Merrick joined as a barber, and within two years he bought the shop. Within ten years he owned six barbershops in Durham and Raleigh, on top of which he sold his own line of grooming products. He accomplished this during the post−Reconstruction era, a time when racial violence and oppression against black citizens were plaguing several southern states.

Merrick was a witty, sociable, outgoing man, a sponge for information and a charismatic networker. He was pals with everyone from the poorest farmers to the wealthiest white business leaders in the city. The barbershop was the perfect stage for his personality, and he loved the barbershop atmosphere of brotherhood, solidarity, and conversation. The shops also enabled him to make valuable connections with white business and community leaders who patronized his business. One of his customers, a wealthy white tobacco man named Washington Duke (who later had a university named after him), gave Merrick hot tips on the Durham property market. By the end of the 1890s, Merrick was one of the biggest real estate owners in the city.

A churchgoing family man with five children, Merrick wasn’t just interested in improving himself; he wanted to help uplift the whole African American community. Since black citizens couldn’t get insurance policies, Merrick and other Durham black leaders joined together to start a “fraternal insurance society,” or “benefit club,” whose members pooled funds to cover accidents, funeral costs, and other expenses. Merrick also helped found a black-owned bank, drug company, real estate company, textile mill, newspaper, and hospital. The net effect of all these ventures was to empower black citizens with jobs and economic opportunity, and to fuel the growth of a vibrant, prosperous black middle class in the city of Durham, which came to be known as “Black Wall Street” and the “Capital of the Black Middle Class.”

In 1898, using a start-up loan from his mentor Washington Duke, Merrick launched his most profitable and enduring achievement, the North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company. This was a dangerous time for a black American to start a business. Racial lynchings were on the rise, and the U.S. Supreme Court had recently legalized segregation with its Plessy v. Ferguson decision. At first, the business struggled. In the first year, premiums totaled less than $500. By the third year, five out of seven partners had quit, and the firm was running at a loss.

But like many American entrepreneurs, Merrick had courage and tenacity to spare. He persisted, powered by a desire to help his community, and he gradually grew his insurance business across the American South, and into what was called the “world’s largest Negro business” at that point in history.

Merrick became one of the most celebrated and respected successful black businessmen of the era, and by capitalizing on an untapped market need—until then, black people couldn’t get insurance—North Carolina Mutual Life became the largest black-owned business in America. “He was a beacon for African American entrepreneurs,” said Kimberly Moore, a modern executive of the company Merrick started. “He was a beacon for African American uplift—economically, socially, educationally. He took a lot of risks. He was saying African Americans needed to be insured. There was an inherent risk of political backlash. But he took a chance. It was pretty revolutionary.” When W. E. B. Du Bois visited Durham in 1910, he was so impressed that he wrote, “There is in this small city a group of 5,000 or more colored people, whose social and economic development is more striking than that of any similar group in the nation.”

Black American entrepreneurs have been contributing to the economic development of the United States ever since day one of the nation. Even in the darkest days of segregation and discrimination, African Americans have been business owners, sole proprietors, product inventors and developers, innovators, publishers, service providers, merchants, artisans, networkers, and investors.

In fact, the rich African American heritage of entrepreneurship dates all the way back to their ancestral homelands across the Atlantic. The victims of the American slave trade were kidnapped and sold (ironically, often by local black African entrepreneurs who did business with white buyers) from areas in West and Central Africa in what scholar Juliet Walker has called “complex, organized, and structured market economies in which they participated as producers, traders, brokers, merchants, and entrepreneurs.” She added that these economies were “propelled by a high degree of both individual and communally based profit-oriented entrepreneurial activities.” As a proverb of Nigeria’s Yoruba tribe puts it, “The world is a market, the market is the world.”

In the early days of American independence, free black entrepreneurs often concentrated in the cities of New England and the upper Atlantic states, but their impact was felt across the nation. In San Francisco, one multiracial entrepreneur, William Alexander Leidesdorff, Jr., was a founding father of the city’s business community, built the city’s first hotel and a successful shipyard and lumberyard, and operated a real estate business in the early to mid-1800s. The whole time, almost nobody knew the light-skinned Leidesdorff had a black African heritage. He served as the city’s first treasurer, and is credited as being America’s first millionaire of black ancestry—in 1856 his estate was valued at $1.4 million, or more than $20 million in today’s dollars.

By the turn of the twentieth century, black leader Booker T. Washington had formed the National Negro Business League and built it to six hundred chapters, and he encouraged African Americans to uplift themselves and their community by launching their own business ventures. By 1920, the League had given birth to a wide range of offshoot organizations, including the National Negro Bankers Association, the National Negro Press Association, the National Association of Negro Funeral Directors, the National Negro Bar Association, the National Association of Negro Insurance Men, the National Negro Retail Merchants’ Association, the National Association of Negro Real Estate Dealers, and the National Negro Finance Corporation.

In both the North and South, many black businesses were often boxed in by social customs to serve black customers only, and this created, by necessity, something of a “golden age” of black entrepreneurship and commerce within the shackles of segregation.

Racial segregation and the geographic concentration of African Americans, in fact, caused many black customers to patronize predominantly black businesses, including black-owned grocery and retail stores, barber and beauty shops, and funeral homes, causing them to flourish and provide a bedrock for the community. For example, explained researchers Vicki Bogan and William Darity, Jr., “in Chicago between 1890 and 1930, the emergence of a considerable Black population and the subsequent segregation of this community facilitated the development of a racially interlocking market on the South Side of Chicago. These Black businesses undertook numerous innovations to overcome the problems of institutional racism, government support of competitors, and other types of discrimination.”

But when racial integration came, paradoxically, it had a damaging effect on many black businesses. “When I was growing up, we had black laundromats and drugstores,” recalled Oakland accountant Herman Morris of his boyhood in Little Rock, Arkansas. “But integration changed all that. All of a sudden—hallelujah—you could work and shop with whites. People turned away from black economic institutions because that was a way of getting away from the past.” Researcher Robert Suggs explained to Inc. magazine in 1986 that this was especially true among middle-class blacks: “It was like an insurmountable trade barrier had dissolved overnight. The traditional black business almost immediately lost its most affluent clientele.”

One group of black entrepreneurs who played a central role in our history was funeral parlor owners, who, as pillars of many African American communities, helped promote the movement for full equality and civil rights in the 1950s and 1960s.

In 1956, funeral home owner William Shortridge helped create the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights to fight segregation and discrimination. Arthur Gaston, who was a highly successful banker, insurance provider, and funeral parlor owner in Birmingham, Alabama, lent Martin Luther King, Jr., a room at his Gaston Motel that became King’s headquarters as he led a turning point in the civil rights movement with his arrest in that city in 1963.

Another business that became a center of community life in many black neighborhoods ever since the end of the Civil War was the black-owned barbershop, where neighbors could talk about their struggles and successes freely, in an atmosphere of fellowship, laughter, and safety.

One day in Baltimore in the late 1940s, a six-year-old black boy named Reginald F. Lewis stepped out of the bathtub and into a towel held by his grandma and grandpa.

During the bath, the boy had heard his grandparents talking about job discrimination against black Americans, and how unfair it was.

Toweling off their boy, his grandparents looked at him and said, “Well, maybe it will be different for him.” Then they asked him, “Well, is it going to be any different for you?”

“Yeah,” said Reginald, “’cause why should white guys have all the fun?”

That question set the tone for the rest of his life, and Reginald F. Lewis went on to become a Harvard-trained lawyer, venture capitalist, and corporate takeover artist, one of America’s greatest black entrepreneurs and philanthropists.

Lewis was also inspired by two simple pieces of advice his grandparents gave him: “Know your job and do it well,” said his grandfather, and his grandmother gave Lewis a tin can and told him to save everything he earned.

Young Reginald pursued both ideas with a passion. He kept his earnings in a tin can known as “Reggie’s Hidden Treasure.” Within two years he built up his paper route from ten customers to one hundred, and was saving eighteen out of every twenty dollars per week he made. He sold the business at a profit, his first coup in an entrepreneurial career that would eventually make business history. In high school, Reginald served as captain of the football, basketball, and baseball teams and was elected vice president of the student body. On weekends and nights, he worked jobs with his grandpa.

Like Madam C. J. Walker and countless other American entrepreneurs, Lewis was filled with a passion for self-improvement, and a vision for achieving it. Early on, he decided that his destiny was to have a career that combined the law and business. In 1961, almost as soon as he enrolled at historically black Virginia State University on a football scholarship, he fell in “love at first sight” with the subject of economics. “I quit football after my freshman year and decided to get serious about my studies. The college years were wild. I crammed a lot of living into those four years. After a rotten freshman year, I really started to study. I got straight A’s in economics and always went beyond the course. I started reading the New York Times and The Wall Street Journal every day.” One of his classmates recalled, “He always had a purpose. Where other guys were taking courses to get out of school, Reggie had a master plan in mind. When other guys were reading comics, he was reading The Wall Street Journal.” He graduated from Virginia State University on the dean’s list.

In 1965, Reginald Lewis’s career path intersected with the legacy of John D. Rockefeller. The Rockefeller Foundation, started decades earlier by the great entrepreneur, financed a summer school program at Harvard Law School to introduce promising African American students to the study of law. Lewis impressed the Harvard faculty so much that they invited him to attend Harvard Law that autumn. He was, in other words, one of the very few students admitted to the law school without even applying! At Harvard, Lewis developed a passion for securities law and mergers and acquisitions, and upon graduating he landed a job with a prestigious New York law firm.

Lewis recalled in his autobiography, “I did the usual work doled out to beginning associates: setting up corporations, preparing joint venture agreements, securities law filings, some not-for-profit corporate work. I worked on a series of transactions involving small venture capital type deals that were particularly instructive, and on several initial public offerings (IPOs) which were then all the rage.”

In 1970, Lewis and a small group of other attorneys started up a black-run New York corporate law firm, and he helped minority-owned businesses obtain badly needed investment capital. Lewis was said to be a tough negotiator and a high-expectations boss, who wanted his employees to give their absolute maximum effort at all times. One of his favorite sayings was “That is not acceptable.”

In 1983, his desire to “do his own deals” led Lewis to become a full-fledged financial entrepreneur, and he opened his own investment company, TLC (The Lewis Companies) Group. Within one year, he closed his first major deal by acquiring the McCall Pattern Company, a home sewing-pattern business that he took over with a leveraged buyout. He financed the deal largely with other people’s money, leveraging $1 million with his capital plus a $24 million loan. He sold the company four years later at a profit of more than $50 million, a return on his own investment of 90 to 1.

In 1987, he created the Reginald F. Lewis Foundation, which funded philanthropic grants to a wide range of artistic, educational, charitable, medical, and civil rights institutions around the world, including historically black Howard University, and his alma mater, Harvard Law School—to which he gave their biggest donation to date.

Also in 1987, Reginald Lewis orchestrated his greatest triumph—the $985 million takeover of the international division of Beatrice Foods, which created the first black-owned billion-dollar company, represented the biggest leveraged buyout of overseas assets by an American company in history, and made him one of the wealthiest African Americans in the nation.

Lewis renamed the company TLC Beatrice International, and suddenly he was in charge of a sprawling global collection of sixty-four companies operating in thirty-one countries, ranging from a sausage producer in Spain and an ice cream maker in Germany to a potato chip operation in Ireland. As chairman and CEO, he moved rapidly to pay down the company’s debt, improve operations, and increase the profits and value of the company. In the process, he expanded his personal wealth to what Fortune magazine estimated at $400 million. With annual sales of $1.5 billion, TLC Beatrice was ranked first on the Black Enterprise Top 100 list of African American–owned businesses ranked on the Fortune 500. “By 1990,” wrote journalist Irene Silverman, “after selling off assets in Latin America and Asia, he had turned the floundering company around, tripling its previous year’s net income and making TLC Beatrice the biggest black-owned company in the U.S.”

Lewis, a devoted family man, moved with his wife, an accomplished attorney, and their two daughters to Paris to run TLC Beatrice’s global business, moving into a historic town house near the National Assembly building. He studied French and collected paintings by Picasso and Matisse.

Reginald Lewis was mindful and proud of his ethnicity, but modest about his historic achievements as a black entrepreneur. “I’m trying not to take it too seriously,” he explained. “It’s tough enough to operate without the added pressure that if I make a mistake, I let down 30 million people. I think of myself as an American of African descent who’s committed to what he is doing. If that work is an inspiration and helps others of my ethnic background, or any other, I’m delighted. But I don’t want it to seep into decisions on how we evaluate our business.” On another occasion, he said to the New York Times, “Unfortunately, when we label people it tends to circumscribe and define them in ways that cut away from their accomplishments. I decided that particularly in my business career, I would do everything I could to avoid that happening.”

In January 1993, after a very sudden onset of brain cancer, Reginald F. Lewis died at only fifty years of age. At his funeral, a statement from his longtime friend, former New York mayor David N. Dinkins, was read. “Reginald Lewis accomplished more in half a century than most of us could ever deem imaginable. And his brilliant career was matched always by a warm and generous heart.” Dinkins added, “It is said that service to others is the rent we pay on earth. Reg Lewis departed us paid in full.”

One of Reg Lewis’s favorite sayings was “Keep going, no matter what.”

Oprah Winfrey was awarded a full scholarship to Tennessee State University and proved to be such a powerful, passionate, and empathetic speaker that she rose to host her own morning talk show in Chicago beginning in 1983. It was so popular that it was soon syndicated nationally and became the highest-rated talk show in TV history. In 1988 she launched her own multimedia company, Harpo Studios, and later became the cofounder of Oxygen Media, which operates a twenty-four-hour cable television network aimed at women. She has produced Broadway shows, major motion pictures, and her own magazine. Following in the footsteps of many great entrepreneurs, Oprah shares her wealth with those in need, and has been named by Businessweek as the greatest African American philanthropist in American history.

By following her passion to communicate with people and make a difference in the world, Oprah Winfrey transformed herself into a global media brand. She became the first black woman on the Forbes “The World’s Billionaires” list, with a net worth of over $3 billion, is the richest African American of the twenty-first century, and is today regarded as arguably the most influential woman in the world.

How did she do it? Oprah was an innovator, creating entire new businesses and brands from scratch. “Everybody has a calling,” she once explained. “And your real job in life is to figure out as soon as possible what that is, who you were meant to be, and to begin to honor that in the best way possible for yourself.” Her calling turned out to be communicating—sharing her authentic curiosity, emotion, enthusiasm, and vulnerability with people around the world.

She was a multimedia operator who understood the synergies of operating in multiple platforms—magazines, movies, theater, and TV, all things she was passionate about. She wrote, “What I know is, is that if you do work that you love, and the work fulfills you, the rest will come.”

She was a bold risk-taker, who smashed expectations and stereotypes with equal fearlessness. “I believe that one of life’s greatest risks,” she noted, “is never daring to risk.” Like many supersuccessful people, she discovered that the secret to success is often failure. “Do the one thing you think you cannot do,” she explained. “Fail at it. Try again. Do better the second time. The only people who never tumble are those who never mount the high wire.” She suggested that you “turn your wounds into wisdom.”

And most of all, Oprah Winfrey was a visionary—a woman who dreamed of helping her fellow human beings and channeled all her passion and energy into achieving her dream. “Create the highest, grandest vision possible for your life,” she recommended, “because you become what you believe.” She explained, “What material success does is provide you with the ability to concentrate on other things that really matter. And that is being able to make a difference, not only in your own life but in other people’s lives.”

Some of the many pace-setting black entrepreneurs of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries include Berry Gordy, Jr., the founder of powerhouse Motown Records; media mogul and Ebony and Jet magazine founder John H. Johnson, a former welfare recipient who became one of America’s wealthiest, richest, and most powerful African Americans; and Brooklyn-born fashion mogul Daymond John of TV’s Shark Tank fame, whose global hip-hop FUBU (“For Us By Us”) brand has generated sales of $6 billion.

“I started working from the time I was six,” John once recalled, “doing everything from selling little pencils in school to shoveling snow in the winter and raking leaves in the fall. When I was 10, I was an apprentice electrician and I used to wire PX cable in abandoned buildings in the Bronx.”

John remembered, “I grew up in a lower-middle-class area of New York City, Hollis, Queens. My parents always instilled in me the fact that I had to work hard for everything that I wanted out of life. And then they got divorced. My father left when I was around 10 years old and I haven’t spoken [to] or seen him again since then, making me the man of the house and making my mother a single mother.”

One of the biggest keys to Daymond John’s business triumph was his mother, a diligent and determined flight attendant who told him to keep his head down and “think big,” and helped him stay mostly out of trouble in a neighborhood that had plenty of negative influences. She provided her son, then age twenty-two, with $100,000 in seed capital by mortgaging their home, then let it become FUBU’s offices and factory. The brand rode the wave of hip-hop culture, which exploded in the 1990s, just as FUBU was starting out.

Early demand for the brand was so high that his mother took out an ad in the New York Times that read, “Million Dollars in Orders. Need Financing.” Thirty-three people called and thirty of them were loan sharks. One of the rest was president of Samsung’s textile division, and he gave FUBU a distribution deal and financing. Barely three years after moving out of John’s mom’s house, FUBU was racking up $350 million in sales.

John has revealed success secrets that many entrepreneurs can relate to, including myself. “You need to outthink, out-hustle, outperform every one of your competitors,” he wrote. “You need to work so hard you’ll wonder how far you can push yourself.”

“I notice a common trait in the super-successful people I meet: Every single one of them . . . has got a killer work ethic.”

“The choice of whether to succeed—or not—is all mine.”

Another epic saga of African American entrepreneurship was written by J. Bruce Llewellyn, the Harlem-born son of Jamaican immigrants who achieved major success in no less than four different businesses: banking, broadcasting, bottling, and grocery stores, becoming one of the nation’s wealthiest African Americans in the process.

Llewellyn grew up with a strong piece of advice hammered home by his father: to succeed in America, black people had to work twice as hard as whites.

As a teenager, Llewellyn worked in his father’s restaurant, read Fortune magazine, and sold Fuller Brush products door-to-door. He graduated high school when he was sixteen, joined the U.S. Army, and became the youngest officer in his battalion. In 1963 he helped launch 100 Black Men, a philanthropic and social alliance that expanded from New York across the nation. “We pushed our guys onto bank boards, into government jobs,” Llewellyn explained to the New York Times in 1976. “We’re the most dynamic group of black men in the country.” In 1973, Llewellyn was appointed chairman and president of the troubled Freedom National Bank in Harlem, and steered it to profitability within three years.

To achieve his next big win, Llewellyn mortgaged everything he had to stage a leveraged buyout of Fedco Foods Corporation, a failing chain of ten supermarkets in the Bronx and Harlem with sales of $18 million. “For an African American businessman to receive multimillion-dollar financing in the 1970s was a landmark event,” marveled investment banker Robert Towbin. Llewellyn tripled the number of Fedco stores and grew sales to $100 million.

In 1985, Llewellyn led a group of black investors to buy Coca-Cola’s troubled Philadelphia bottling company. “Llewellyn consolidated plants and warehouses from seven to two, cut the number of employees and increased annual production to 30 million cases, from 9 million when he took over,” reported Forbes. “Yes, I was the first minority bottler,” Llewellyn recalled, “but no, the fact that I was qualified as a buyer with proven experience with finance and retailing had nothing to do with my color.” Also in the 1980s, Llewellyn and his partners moved into the TV business, buying Buffalo’s WKBW-TV from ABC/Capital Cities for $56 million, and buying Garden State Cable for $420 million.

His success, reported Llewellyn in an interview with The Black Collegian in 1997, didn’t come easy, but instead was “nerve-wracking, gut-wrenching and pain inducing.” He said, “You must act to acquire it with a vengeance and to pursue it with a passion.”

“Minorities have to understand that the world revolves around the golden rule,” he wrote in a 1990 Fortune magazine article that argued that social and political power come from economic power. “Those who have the gold, rule.”

In recent years, some sectors of black-owned businesses have shrunk, after being hammered both by economic downturns and by fierce competition from national chain companies, which have affected many nonblack companies as well.

In the March 2017 issue of Washington Monthly, “The Decline of Black Business” reported that “[t]he last thirty years also have brought the wholesale collapse of black-owned independent businesses and financial institutions that once anchored black communities across the country. In 1985, sixty black-owned banks were providing financial services to their communities; today, just twenty-three remain.” The National Funeral Directors and Morticians Association has seen its membership plunge by 40 percent since 1997. Black Enterprise magazine termed the 1990s “a virtual bloodbath” for the black insurance industry, as the number of black-owned insurers dropped by 68 percent, with much of their business lost to mainstream giant insurers, who increasingly catered to the lucrative African American market.

Paradoxically, some of the decline in African American entrepreneurship may have come from greater opportunities opening up for black citizens in many professional fields, giving them more choices beyond starting their own business. The integration of many suburbs, certainly a positive trend, has had the negative effect of weakening black-owned small businesses in black neighborhoods.

Today, black Americans lag behind whites and other minorities in rates of business ownership, but the gap has been narrowing in recent years, and by 2011, African American–owned businesses totaled some two million, and enjoyed the highest growth rate in the number of minority-owned companies from 2002 to 2011.

Overall, African American entrepreneurs have come a long way in recent decades. The total combined revenues of companies on the Black Enterprise 100 list now totals over $24 billion, a ninefold rise, after adjusting for inflation, since 1973.

American women have always been key players in American entrepreneurship—as business pioneers in their own right, and in critical leadership and support roles for their husbands and families.

In many cases, like my own, they have acted as inspirers, advisors, sounding boards, and key decision makers for the business careers of their spouses. My wife, Korie, is a full partner in everything I do, and that’s especially true when it comes to business. She grew up in a business family.

As a young girl, Korie worked in her grandfather’s jewelry store cleaning the glass counters and wrapping Christmas gifts. Her family launched more than twenty business ventures, including Howard Brothers Discount Stores, which is the chain of stores my own mother worked for. The company was very successful, went public, and had seventy-eight stores all across the Southeast before the family sold it in 1978.

The Howards started a new chain in 1984 called the SuperSaver Wholesale Warehouse Club, built it up to twenty-four stores in less than two years, and in 1987 sold the business to Sam Walton of Walmart fame, who turned them into Sam’s Clubs. Later, Korie’s family started a publishing company, which was eventually sold to Simon & Schuster. For five years in a row, that company won “Best Christian Workplace in America.” Not bad! Her family also started a summer camp, and it’s a good thing they did, since that’s where I met her. Today, Korie’s father works for us at our company, on a wide range of management, budget, and contract issues. He is a huge asset to our businesses.

With all this entrepreneurship in her DNA, Korie is way smarter in business than me. She’s more of a risk-taker, too, probably because I grew up poor and she grew up a little wealthier. I’m more conservative, and she’s more inclined to take a chance.

The American tradition of women as powerful forces in business dates back to the early days of the young republic, when female American entrepreneurs ran retail shops, hotels, and taverns, sometimes because it was the best way to earn a living if a male breadwinner wasn’t around. Women started businesses from scratch and they inherited businesses from their relatives and spouses.

The first prominent American female CEO was Rebecca Lukens of Pennsylvania, who, starting in 1825, transformed her family’s near-bankrupt Brandywine Iron Works and Nail Factory into a successful steel enterprise that operated into the twenty-first century. “Rebecca was able to build the company up into one of the major players in the iron business, winning commissions for sea-going vessels and contracts for locomotives and Mississippi steamboats,” wrote historian Kat Michels.

As a negotiator, Rebecca Lukens was known for being as tough as her factory-produced nails, but she was a kind, benevolent employer who provided housing, good working conditions, and bonuses to her workers. Under her leadership, Brandywine became America’s leading producer of boiler plate. In 1994, Fortune called Lukens “America’s first female CEO of an industrial company,” and also inducted her into the National Business Hall of Fame.

In the twentieth century, millions of women entrepreneurs stepped up to the challenge of running their own business. Women won the right to vote and helped achieve victory on the home front in World War II, and women-owned businesses rose from 600,000 in 1945 to nearly one million by 1950, helping to power America’s stunning postwar economic boom.

Many of these businesses were started on kitchen tables, amid grocery bags and diaper boxes, as women juggled the demands of domestic life with visions of financial achievement.

In the 1940s, Ruth Handler and her husband began a toy business in their garage workshop in California. Their first hits were the Uke-A-Doodle miniature ukulele, a hand-cranked music box, and the Burp Gun toy weapon. But the success of their Barbie doll line (named after the couple’s children Barbara and Ken) and Hot Wheels toy cars captured the imagination of the world’s children and by the 1960s pushed the company into the Fortune 500. Today Mattel has global revenues of over $5 billion.

Lillian Vernon started her catalog business out of her apartment when she was pregnant with her first child. She named the company after herself and built it into the first company founded by a woman to be publicly traded on the American Stock Exchange, and spent fifty-one years as the company’s CEO.

Martha Stewart’s lifestyle empire began as a catering business in her basement. Liz Claiborne turned her fashion brand start-up into the first Fortune 500 company founded by a woman by catering to the tidal wave of women entering the workforce in the 1970s and 1980s. By the 1980s, women owned 25 percent of American companies.

In 1974, a time when relatively few women had entered technology, Sandra Kurtzig started a business in her spare bedroom that became ASK Computer Systems, which became one of the fastest-growing computer software companies in America. In 1981, she was the first woman to lead a technology company public stock offering. By 1992, sales reached the $450 million mark.

In 1996, at the age of twenty-five, Ecuadorian immigrant Nina Vaca, the daughter of an entrepreneur, started information technology service provider and staffing agency Pinnacle Technical Resources with $300. By 2013, revenues had grown to $200 million. In 2017, she told Forbes, “Confidence was instilled in me at a very, very young age. I have two teenage daughters, 16 and 17 years old, and I try to instill that same confidence in them. I tell them, ‘Confidence is the best outfit you can wear.’ Lack of confidence can be something that holds us back as women. We need to unequivocally, absolutely have confidence in our skills and our worth because people detect a lack of confidence very quickly. We have to be confident in our abilities, in what we represent and in what we bring to the table.” She added, “The future of entrepreneurship continues to be very bright. Technology has lowered the barriers to entry for small businesses so we’re seeing those numbers grow dramatically. Women and immigrants continue to over-index in starting small businesses. In fact, Latino-owned businesses are one of the fastest growing segments. Entrepreneurship has always been an incredible engine for America and I see no reason why that will change anytime soon.”

Mary Kay Ash wrote her own inspiring tale of entrepreneurship, starting off as a single mother at age twenty, eventually building a $1 billion cosmetics and skin-care company, and being named the most outstanding twentieth-century businesswoman by the Lifetime TV network and the top female entrepreneur in American history in a Baylor University study.

Mary Kay was born in Hot Wells, Texas, the daughter of a mother who was the breadwinner for the family. She was married at age seventeen and had three children before her husband divorced her. She worked for Stanley Home Products as national training director, but quit when a man she had trained was promoted above her at twice her salary. She started writing a book about how women could thrive in business by following the Golden Rule: “Do unto others as you would have others do unto you.” Then she realized she could build a company on it, too.

She started her business in 1963 with a small start-up budget of $5,000 and the help of her son. “The soothsayers prophesied that I was doomed to failure,” she wrote. “However, I was determined to prove them wrong.”

Did she ever. By 1973 Mary Kay products were being sold by over 21,000 beauty consultants or independent sales agents. Like Madam C. J. Walker, her corporate philosophy was to empower women by enabling them to generate their own income, and to shower her sales agents with praise, rewards, enthusiasm, and positivity. She gave them incentives like jewelry, vacations, and the chance to drive a Mary Kay career car—including the iconic pink Cadillac—and super-high-energy sales conventions that felt like a biblical revival meeting.

One of the biggest keys to Mary Kay’s success was the fact that she took the Golden Rule further than most other business leaders do, to the point where she pictured every person she met as having a sign around their neck that read, “Make me feel important.” She explained that her philosophy was to “praise people to success,” and “If you let people know you appreciate them and their performance, they’ll respond by doing even better.” One employee said that “she made everyone feel important whether it was the maintenance man who took care of the building to our top salespeople.”

Mary Kay also believed in the positive power of failure. “We fall forward to success,” she said. “We learn from our failures.” She wrote: “I’ve found that successful people are never afraid to try because they are never afraid to fail.” She shared that inspiration with employees. “Don’t limit yourself. Many people limit themselves to what they think they can do. You can go as far as your mind lets you. What you believe, remember, you can achieve.”

Today, Mary Kay Inc. is one of the world’s biggest direct-sales cosmetics companies, boasting over $3.5 billion in sales and over two million sales agents.

In 1948, a woman from Brooklyn began selling a line of skin-care products at her own counter at New York City’s Saks Fifth Avenue luxury superstore.

The products were developed by her uncle, who was a chemist. The woman, a daughter of Jewish immigrants from Europe who was originally named Josephine Esther Mentzer, now called herself Estée Lauder, which was also the name of her start-up beauty company, which she founded with her husband. She had grown up working in the family’s hardware store, where she learned valuable lessons in entrepreneurship and retail business operations. Now she was using a former restaurant kitchen to mix up some of her own skin cream concoctions, which were based on her uncle’s formulations.

In the face of Lauder’s constant pestering to let her into his store, the Saks Fifth Avenue buyer said he foresaw no demand for her products. She promised to prove she would succeed, if he only gave her a chance. “I have never worked a day in my life without selling,” she later explained. “If I believe in something, I sell it, and I sell it hard.” He gave in. She sold out her stock in two days, and right away, Saks ordered more.

Lauder had no marketing budget, so she started giving away product samples right in the store. Her competitors thought she was crazy. She was going up against entrenched giants like Revlon and Elizabeth Arden. Everyone was convinced she would run out of product and go broke fast. Instead, she built a multibillion-dollar business that continues to thrive to this day, a business that includes cosmetics and fragrance powerhouse brands Estée Lauder, MAC Cosmetics, Prescriptives, Origins, Aramis, and Clinique.

The company’s success was largely based on Estée Lauder’s personal energy, enthusiasm, and passion for marketing. “She was devastatingly sincere and insistent about the products, knowing that if people tried them they would glow,” wrote authors Harold Evans, Gail Buckland, and David Lefer in their book They Made America. “In chance encounters in elevators, on trains, in hotels and stores, trapped under a hair dryer, no woman was safe.” Lauder wrote in her autobiography, “Good was not good enough. I know now that obsession is the word for my zeal. I was obsessed with clear glowing skin, shining eyes, beautiful mouths.”

In 1998, when Time magazine ranked the twentieth century’s “most influential business geniuses,” Estée Lauder was the only woman on the list. By the time she died six years later at the age of ninety-five, her company’s annual sales had passed $5 billion.

Estée Lauder in the field, demonstrating her lipstick on a customer. (Library of Congress)

In 2017, business network CNBC reported that “the Golden Age for women entrepreneurs has finally begun. The stars have aligned to help trigger the trend as robust ecosystems churn out enterprising females equipped with inspiration, know-how, and funding. In recent years, the rate of women entrepreneurs has been growing at a percentage at least double that of their male counterparts.”

Between 1997 and 2013, the number of woman-owned firms in the United States rose by 59 percent, which was one and a half times the rate of the national average. Businesses owned by women ethnic minorities are growing especially fast. Today, the 7.7 million American firms that are majority-owned by women employ over 7.1 million people and account for $1.1 trillion in sales, according to the Center for Women’s Business Research.

According to 2014 figures from the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation, women-owned enterprises now account for nearly 30 percent of all companies. In 2016, there were an estimated 11.3 million women-owned businesses in the United States—a 45 percent increase since 2007, according to the 2016 State of Women-Owned Businesses Report from American Express.

Latino entrepreneurs have had a rich history in America, even in the centuries before the birth of the United States.

At first, Latino enterprises were concentrated in the American Southwest, plus Florida, Louisiana, and New York. Early Latino entrepreneurs in America included Tomás Menéndez Márquez, owner of the gigantic La Chua Ranch in Florida. He produced over one-third of Florida’s cattle stock in the seventeenth century and shipped hides, dried meat, tallow, and trading goods throughout the Caribbean. Márquez and his successors carved out the first trading networks in Florida, often following routes pioneered by Native Americans before them.

Mexican entrepreneurs operated large-scale livestock ranching operations across the present-day American Southwest, in Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and California, supplying mining and farming customers. Many ranches stayed in business long after the Mexican-American War. “In 1760, for example,” wrote historian Geraldo L. Cadava, “Captain Blas María de la Garza Falcón received from the Spanish crown a 975,000-acre land grant in Texas, which he called Rancho Real de Santa Petronila. Much of it later became the King Ranch, which, at half a million acres, was the largest ranch in the U.S.”

In the 1800s, the nine-hundred-mile Santa Fe Trail from St. Louis to Mexico was a trading superhighway that provided business and jobs for thousands of Mexican entrepreneurs, including farmers, miners, ranchers, street vendors, general store owners, and other merchants.

Two Mexican American brothers, Bernabé and Jesús Robles, seized the opportunity of the federal Homestead Act of 1862—which offered cut-price land in the West to those who would make it productive—to build a cattle empire that became the Three Points Ranch in southern Arizona and eventually totaled one million acres. Also in the mid-1800s, pioneering Mexican American entrepreneurs like Joaquin Quiroga and Estevan Ochoa operated wagon-hauled freight shipping enterprises that carried products between Mexico and the United States and across the Southwest.

In the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, Latino culture, products, and businesspeople spread throughout the nation, fueled by economic and political immigration from Cuba, Mexico, Puerto Rico, and elsewhere in Latin America. New York City became a mecca for entrepreneurs of Cuban and Dominican heritage, Miami became a capital of Cuban American commerce, and states on the southern border provided a home for many Mexican American small businesses. Today, the impact of Latino American entrepreneurship is felt in cities and communities across the country.

Among the many thousands of successful Latino American entrepreneur stories are those of Los Angeles Angels owner Arturo Moreno, the first Latino to own a major U.S. sports franchise; Angel Ramos, who founded Telemundo, the second-largest Spanish-language network in the United States; and the Unanue family, who built Goya Foods into the largest Latino-owned food distributor in America.

The Latino share of American entrepreneurs grew from 10.5 percent in 1996 to almost 20 percent in 2012, and in 2014 their combined revenue was over $450 billion, an increase of 100 over the previous six years.

The impact of Asian American entrepreneurs is substantial, too, in American medicine, technology, and many other sectors. “As leading actors in the U.S. economy, Asian American entrepreneurs’ contributions cut across all segments,” said Dilawar Syed, a member of the President’s Advisory Commission on Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, in 2011. “They are innovators in technology start-ups in Silicon Valley; they operate restaurants and convenience stores in neighborhoods across the U.S.; they run medical clinics, often in underserved communities. Fundamental to this mosaic of entrepreneurial success stories is a set of core characteristics: a strong work ethic, a disciplined pursuit of education, and an unshakeable faith and optimism about the country’s future.”

Nearly 60 percent of Asian American businesses are headquartered in only four states—Texas, California, Hawaii, and New York. One booming segment is Asian American women entrepreneurs, who already account for 39 percent of the total.

Every morning, millions of these business heroes wake up to chase the American dream—heroes of every background and faith, including men, women, minorities, Native Americans, veterans, millennials, seniors, and disabled citizens.

They are all American entrepreneurs.

They all have a rich, powerful heritage in common—and a fair shot at a great future for themselves, their families, and their communities.