The Golden Age of the American Entrepreneur

Try not. Do! Or do not. There is no try.

—Yoda

The United States is the engine of today’s business world, and entrepreneurs provide much of its fuel.

The twentieth and twenty-first centuries have been a golden age for American entrepreneurs, the men and women who powered and sustained much of America’s global economic leadership through two world wars, social upheaval and progress, globalizing markets, and the dawn of the space and information ages.

This is a golden age for my own family, too, as we struggled and hustled for over forty years to achieve many of our own dreams by working together in the family business. As the New York Times put it in 2013, “Forget the ZZ Top beards and the Bayou accents, the Robertsons of West Monroe, La., are a family of traditional American entrepreneurs: ambitious, rich and spectacularly successful. And that was true even before they were television stars.”

A few years ago, we shattered ratings records in the cable TV business when nearly twelve million people tuned in for our season premiere. Our show has aired in more than one hundred countries, pulling in strong ratings on networks from the United Kingdom to Latin America. Someday I’ll probably be floating down the Amazon in a tour boat and a local fan on shore will holler, “Hey, aren’t you that Duck Dynasty guy?” We’ve achieved success in the businesses of duck and deer hunting gear, rifles and ammunition, outdoor accessories, videos, DVDs, fashion and clothing, shirts, caps, coolers, restaurants, books, music, personal appearances and events, and the music industry.

It’s hard sometimes to keep track of all our products. One day, when I was visiting the corporate headquarters of Walmart, I was startled to see my face on a garden gnome. I must say he was a handsome little guy, but I was surprised to see him. I knew I had a Chia Pet and a bobblehead and an action figure, but I didn’t know I had a garden gnome. That’s awesome, but I thought it was kind of weird—until the day I saw myself on a Pez dispenser.

Beyond my own family, there are scores of modern-age American entrepreneurs who have inspired me with their courage, genius, and tenacity. Here are just a few of my favorite stories.

In 1906, two brothers had a fight over breakfast cereal.

They had been working together for over twenty years, they were having a business dispute, and they were finally at the breaking point. It was a sibling rivalry that Entrepreneur magazine later reported “ranks up there with that of Cain and Abel.”

The older brother, Dr. John Kellogg, was the boss. He ran a famous health retreat, or “sanatorium,” in Battle Creek, Michigan, that was based on principles of healthy living, vegetarianism, and a low-protein, low-sugar, low-fat diet that focused on whole grains, fiber, and nuts. Their family had fourteen children, in an observant Seventh-Day Adventist household that honored a Saturday Sabbath and abstained completely from meat, coffee, tea, tobacco, and alcohol.

Years earlier, the doctor had hired his brother, Will Kellogg, who was eight years younger, to run the day-to-day business operations of the sanatorium, as well as their mail-order cereal business. He treated Will badly and paid him poorly. John made Will trot alongside him as he bicycled around the sanatorium and required Will to take dictation while he used the toilet. Will’s pay was so low that he wasn’t sure how he could properly support his family. “I feel kind of blue,” Will confessed to his diary. “Am afraid that I will always be a poor man the way things look now.”

Despite John’s rude treatment, Will quietly flourished as a hands-on family entrepreneur. According to author Howard Markel, “Will was a serious student of the emerging science of business and methodically analyzed, applied, and adopted efficiency techniques and systems espoused by the best commercial gurus of the day. For nearly a quarter century, the quiet, stolid Will was doing more than merely taking orders. He was preparing to become a renowned captain of industry. Just as Henry Ford was figuring out the economies of scale to sell millions of automobiles rolling off his assembly line, Will Kellogg revolutionized the administration of the modern medical center and, later, the mass production and marketing of manufactured food.”

By 1900, after fourteen years of expansion by the Kellogg brothers, the sanatorium had become what Markel called “a massive, modern, beautiful and luxurious medical and surgical center; it was so grand that it employed over 1,000 people, cared for seven to ten thousand patients each year, operated dozens of laboratories and radiology units, farmed over 400 acres of land to grow the vegetables, fruit and dairy products the guests consumed daily, and operated a canning and food manufacturing facility, laundry, charity hospital, creamery, and a resort comprising 20 cottages.”

For years, the brothers had been making experimental batches of healthy alternative foods. One day in 1898, in an accidental baking discovery, they created a scrumptious, dry, “toasted cereal flake” or “flaked wheat berry” from a batch of boiled wheat paste that had been left out too long. John wanted to serve the flakes crushed up, but Will insisted they be served whole. The Kellogg’s corn flake was born. People loved the taste and gobbled up bowls full of it at the sanatorium.

Will thought these tasty flakes were the future of the American breakfast.

His brother John disagreed.

Will quickly discovered that the process worked just as well with oats, rice, and corn. But although it was Will Kellogg who had stumbled upon the creation, it was John who took all the credit, claiming the idea had come to him in a dream.

Will wanted to protect their recipe, move production off-site, and advertise heavily to gear up for bigger sales. John wanted to make it at the sanatorium instead, and show everybody how they did it. One guest patient, C. W. Post, watched carefully, and used the process to create his own company, Postum Cereals, in 1904, which later became General Foods. He soon made a fortune with products like Grape-Nuts, inspired by the Kellogg brothers’ idea. John Kellogg didn’t mind, but his little brother Will was furious.

This was the last straw. Will, who was often called “W.K.,” cut ties with his brother and in 1906 launched his own venture, the Battle Creek Toasted Corn Flake Company, which later became the Kellogg Company. “I sort of feel it in my bones,” he told a friend, “that we are preparing a campaign for a food which will eventually prove to be the leading cereal of the United States, if not the world.” Boy, did he turn out to be right.

But at first, the going was tough. Real tough. As in: “There are already forty other companies producing cold cereal in the American market, and oh, by the way, our factory is on fire!” tough.

On July 4, 1907, Kellogg watched as his first factory burned to the ground. “He had no capital to rebuild, but with the ruins still smoking, he told his employees to report for work the next morning,” wrote Kellogg executive La June Montgomery Tabron in 2014. “By the day’s end, he had arranged for an architect to begin plans for a much larger and safer factory. Then, he somehow drummed up the financing to make it a reality.”

Will Kellogg rebuilt his factory operations with state-of-the-art assembly line technology, put prizes in his cereal boxes, staged sample giveaways of his new products, and ran ads featuring a farm girl known as the “Sweetheart of the Corn.” In 1912, Kellogg unveiled the world’s biggest advertising billboard to date, measuring 50 feet high and 106 feet wide. “Mr. Kellogg appreciated the power of the new force that was beginning to be used by progressive businessmen—the force of consumer advertising,” wrote biographer Horace Powell. “Visualizing his foods on breakfast tables in millions of homes, he knew that the entrée to these homes was chiefly through advertising.”

On a personal level, Will Kellogg wasn’t the warmest guy you’d ever met—his employees found him demanding and distant—but he treated them better than many other employers. He gave them health care and a nursery, paid better-than-average wages, helped them through the dark days of the Great Depression, and cut the workday from the normal ten hours to eight. The two Battling Brothers of Battle Creek sued each other over which one could market cereal under the Kellogg name. After court proceedings that dragged on for years, Will Kellogg won, his brother withdrew in obscurity to Florida, and Will’s company went on to become wildly successful and led the global market for ready-to-eat cereal.

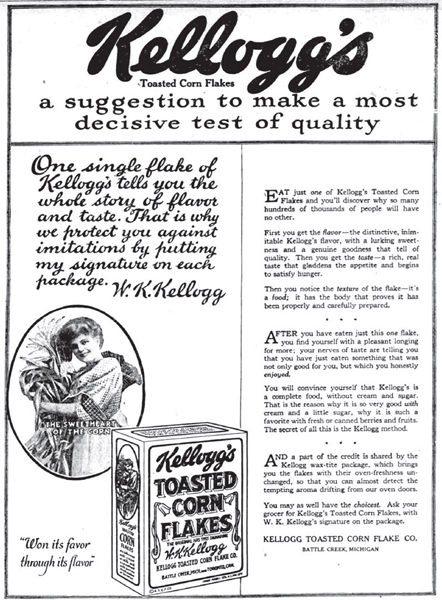

A Kellogg’s advertisement from 1919. (The Oregonian)

Workers in a Kellogg’s factory in 1934. (U.S. National Archives)

As a result, Will Kellogg became one of the wealthiest people in the United States. In the great tradition of many successful American entrepreneurs, he put his money to good use—by helping his fellow human beings. In the 1930s, he started the W. K. Kellogg Foundation to support children’s health care and education, and eventually endowed it with almost all of his equity in the Kellogg Company. Today, thanks to its 34 percent ownership of Kellogg Company, the foundation is one of the world’s biggest private charities.

One of the most colorful American entrepreneurs ever born was a brilliant banker from Boston by the name of Joseph P. Kennedy.

With a genius for marketing and publicity and a massive bank account, Kennedy engineered a family takeover of the most powerful piece of real estate in American history—the Oval Office.

The charming, sandy-haired Kennedy was, in the words of one writer, a “ruthless businessman and investor” who “capitalized on his wealth to become perhaps America’s premier social climber, an Irish-Catholic outsider who stormed the bastions of the WASP aristocracy.”

Son of a middle-class Boston tavern owner, Joe Kennedy attended Harvard and became a banker and financier, propelled by a hunger for family prestige, wealth, and social and political power. In a brilliant move, Kennedy cashed out most of his stock holdings just before the Crash of 1929, shielding his family’s wealth from the ravages of the Great Depression. “From the beginning, Joe knew what he wanted—money and status for his family,” said a close friend. Kennedy had a confident, quick smile, a firm handshake, and a meticulous personal style, which featured a wardrobe that was hand-tailored (down to his underwear) in London and Paris.

By the 1930s, Kennedy was well on his way toward amassing a personal fortune that the New York Times valued at $500 million at the time of his death in 1969. He earned his money through a wide variety of entrepreneurial ventures, including banking, real estate, corporate takeovers and consulting, liquor importing, and movie production. Movie superstar Gloria Swanson, who was Kennedy’s mistress and management client before he double-crossed and abandoned her, recalled that Kennedy “operated just like Joe Stalin”: “their system was to write a letter to the files and then order the exact reverse on the phone.” When she met Kennedy, Frances Marion, America’s highest-paid screenwriter at the time, thought, “He’s a charmer. A typical Irish charmer. But he’s a rascal.”

In a stunning four-year raid on Hollywood, Kennedy took over three movie studios and ran them each simultaneously, launched the talking-picture revolution, established the prototype of the modern motion-picture conglomerate, and cashed out with millions of dollars in his pocket. Betty Lasky, daughter of Paramount founder Jesse Lasky, observed, “Kennedy was the first and only outsider to fleece Hollywood.”

Joe Kennedy was a master manipulator of money and people. In the words of a January 1963 profile in Fortune, he was “a smart, rough competitor who excelled in games without rules. A handsome six-footer exuding vitality and Irish charm, he also had a tight, dry mind that kept a running balance of hazards and advantages. Quick-tempered and mercurial, he could move from warmth to malice in the moment it took his blue eyes to turn the color of an icy lake. Friendships shattered under the sudden impact of brutal words and ruthless deeds, yet those who remained close to him were drawn into a fraternal bond.” Kennedy had, in the opinion of one colleague, a gift for speculation, based on “a passion for facts, a complete lack of sentiment, a marvelous sense of timing.”

Joe Kennedy wanted to be president of the United States, but he had a big mouth, a flaw that sank his political career. In 1940, when he was ambassador to the United Kingdom, he blurted to a reporter, “Democracy is finished in England.” With that remark and the firestorm of bad press it triggered, Kennedy’s career in public service was over. He resigned under pressure and transferred his ambitions for political power to his children, Joseph Jr. and John, both of whom he could envision capturing the White House someday—with his help. When Joseph Jr. was killed on a combat mission in Europe, the mantle fell on John’s shoulders.

Joseph P. Kennedy in 1938, when he was ambassador to the United Kingdom. (Wide World Photos)

During the Christmas holiday of 1948, at his beachfront mansion in Palm Beach, Florida, Joseph P. Kennedy held a series of intense, private discussions with his son John, a thirty-one-year-old U.S. Navy veteran and hero of service in the South Pacific during World War II. After some reluctance, the shy son agreed to his father’s master plan to thrust him into national politics.

“We’re going to sell Jack like soap flakes,” boasted the elder Kennedy, and over the next twelve years, Joseph acted as the behind-the-scenes CEO of JFK’s stunning rise to the presidency. In each campaign—for the House of Representatives in 1946, the U.S. Senate in 1952, and the presidency in 1960—Joseph Kennedy, working in the shadows, took charge of JFK’s campaign marketing, publicity, strategy, and research. His nearly unlimited checkbook paid for a vast amount of campaign literature, direct mailings, and broadcast advertising, as well as political payoffs.

JFK went on to become one of the most admired presidents in modern history. Privately, he said of his entrepreneur father, “He’s the one who made all this possible.”

One day in 1928, a train pulled out of New York City’s Grand Central Terminal, heading for Hollywood.

On board the train was a twenty-six-year-old cartoon illustrator, high school dropout, and former World War I ambulance driver who had started an animation company with his brother in their uncle’s California garage.

The young man had a pipe and a mustache in order to look suave and sophisticated. But on this day he was seething with anger, and acting, according to his wife, “like a raging lion.”

His name was Walt Disney.

He had two failed companies and one bankruptcy behind him, and his latest venture, a movie cartoon series about his creation “Oswald the Lucky Rabbit,” had just blown up in his face. At a meeting in New York, Disney had discovered that his distributor had taken the rights to the popular cartoon away from him, cut his pay, and swiped his employees to boot. Now he had no income, no job, no contract, and no staff. It also looked like he’d run out of adorable cartoon animals to draw for profit, since rabbits, dogs, cats, and bears were already taken.

It was a moment of pure personal and professional despair, the kind of moment that can sneak up and strike many an entrepreneur during their career, even multiple times. But it was a moment some of us are born to master. As Disney explained, “Disaster seemed right around the corner,” and “I function better when things are going badly than when they’re smooth as whipped cream.”

As the cross-country train barreled westward, a furious Disney gathered his thoughts and did what he did best. He started doodling and sketching designs on a drawing pad. Then, Disney recalled, a creature “popped out of my mind” onto the paper.

By the time the train pulled into Kansas City, Disney had created a cute little mouse, a plucky rodent who wore red velvet pants and seemed born for adventure and hijinks.

Walt wanted to call the creature “Mortimer,” but his wife hated the name. “Too sissy,” she declared. They talked it over and settled on Mickey. “It’s better than Mortimer,” she said.

The new character, born in a moment of desperation, launched Disney’s new studio and put it on a thirty-year path to become one of the world’s leading entertainment companies. “Mickey Mouse is, to me, a symbol of independence,” Disney remembered. “He was a means to an end. Born of necessity, the little fellow literally freed us of immediate worry. He provided the means for expanding our organization to its present dimensions and for extending the medium of cartoon animation toward new entertainment levels. He spelled production liberation for us.” He added, “All we ever intended for him or expected of him was that he should continue to make people everywhere chuckle with him and at him. We didn’t burden him with any social symbolism; we made him no mouthpiece for frustrations or harsh satire. Mickey was simply a little personality assigned to the purposes of laughter.”

An epic series of movies, TV shows, theme parks, and entertainment products flowed out of Walt Disney Studios. They include Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Fantasia, Dumbo, Pinocchio, Bambi, The Mickey Mouse Club, Mary Poppins, Epcot, Walt Disney World, Walt Disney Parks and Resorts, and Disneyland, a project for which Disney mortgaged everything he had, including his personal insurance, to build in 1955. Today, more than fifty years after Walt Disney’s death, the company he founded is a thriving media mega-powerhouse, with a market value of around $150 billion.

A U.S. postage stamp of Walt Disney. (USPS)

And it all started with one young man, a failed entrepreneur, and a little mouse on a drawing pad. “You may not realize it when it happens,” Disney once said, “but a kick in the teeth may be the best thing in the world for you.”

One day in 1939, two engineering students at Stanford University decided to create a start-up technology company in a humble garage at 367 Addison Avenue in Palo Alto, California.

They wound up creating much of what the world now calls Silicon Valley.

The two young men weren’t sure whose name should go first in the new company’s name. So they flipped a coin. The winner of the toss was a humble and friendly man named William Hewlett, who was a brilliant mathematician and tinkerer who struggled with dyslexia as a child. By the time he was in high school he had built an electrical transformer and a crystal radio set.

The company he formed with David Packard, christened Hewlett-Packard (or “HP”), started off with $538 in working capital. Hewlett slept in a shed near the garage, Packard in a nearby apartment. The partnership of these two men changed the world of technology.

Hewlett-Packard’s first product was an audio production device used by Walt Disney Productions in making the 1940 classic movie Fantasia. Over the next four decades, the company came out with a long series of innovative, breakthrough products that regularly outflanked its competitors. They included in 1951 the high-speed frequency counter that was used by radio stations to meet FCC requirements, in 1964 the cesium-beam standard clock that fixes international time standards, in 1968 and 1972 the first desktop and scientific hand-held calculators, in 1982 the first desktop mainframe computer, and the pacesetting HP LaserJet printer series. By 2009, HP had sales of $114.6 billion.

The company was based on “the HP Way,” a set of principles that Bill Hewlett explained as “a deep respect for the individual [and] a dedication to affordable quality and reliability,” in order to make products that help all of humanity.

But according to management expert Jim Collins, the HP Way was not just about benevolence and charity. “Packard and Hewlett demanded performance, and if you could not deliver, the HP Way held no place for you,” Collins wrote. “Therein we find the hidden DNA of the HP Way: the genius of the And. Make a technical contribution and meet customer needs. Take care of your people and demand results. Set unwavering standards and allow immense operating flexibility. Achieve growth and achieve profitability. Limit growth to arenas of distinctive contribution and create new arenas of growth through innovation. Never compromise integrity and always win in your chosen fields.”

The success of HP was an inspiration to other young entrepreneurs who launched digital ventures in the Silicon Valley–style “garage start-up culture,” like Apple, Google, Cisco, Intel, Facebook, Uber, and Airbnb, along with so many others.

On April Fool’s Day in 1976, twenty-one-year-old Steve Jobs and his twenty-five-year-old buddy Steve Wozniak started Apple Computer in Jobs’s parents’ garage in Los Altos, California. Under Jobs’s charismatic, impassioned leadership, Apple went on to become the world’s largest information technology company and a prime force behind the world’s digital revolution, with culture-shaping products like the Macintosh computers line, the iPod, the iPhone, the Mac operating system, Final Cut Studio, iTunes, and the iPad. By 2010, Apple’s market value had passed that of software and Internet colossus Microsoft, whose college-dropout entrepreneur founder Bill Gates has become one of the world’s wealthiest people, with a net worth of some $80 billion.

Google was started in 1998 by Stanford University doctoral students Sergey Brin and Larry Page with an investment of only $100,000. Just ten years later, Google’s parent company had reached $820 billion in market value as the world’s largest search engine.

Today, the one-car garage where Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard launched both Hewlett-Packard and the Silicon Valley technology revolution is honored as a California historic landmark and is on the National Register of Historic Places.

Some modern-day American entrepreneurs have revolutionized their industries.

Take Alfred Sloan, for example—not a name you hear much nowadays, but a man who was a founding father of American business. He was a ball-bearing company owner who sold his business to General Motors in 1916 for $100 million in today’s dollars, eventually became GM’s president, and had built it to annual revenues of $20.7 billion when he died. “Sloan was a business genius who turned GM into the largest company in the world,” said author David Farber. “And he, more than any other individual, invented modern corporate management and created the form of consumer capitalism that characterized much of 20th century America.”

Or consider Sam Walton, who started off as a small businessman and did more in his time to change the face of the world of retail than anybody else. In 1945, he opened his first general store with a $25,000 loan from his father-in-law. The first official Walmart was opened in Rogers, Arkansas, in 1962. Today, mass retailer Walmart is the world’s largest company by revenue, has over eleven thousand stores, and is the biggest private employer in the world.

The original Walton’s Five and Dime in Bentonville, Arkansas, the store that spawned a multibillion-dollar empire. (Bobak)

In 1942, during World War II, industrialist Henry J. Kaiser founded Kaiser Permanente, the world’s first health-care organization, to keep his employees productive and in good health. As a construction entrepreneur in the 1930s who overcame humble beginnings, Kaiser led companies that built some of the greatest projects of the twentieth century, including the Hoover Dam in Nevada, the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge, and the Grand Coulee Dam in Washington. His more than one hundred companies made everything from ships to cars to houses. During World War II, Kaiser Shipyards produced nearly 1,500 ships, more than any other company.

His greatest legacy is Kaiser Permanente, which today is America’s biggest health maintenance organization. “I make progress by having people around me who are smarter than I am and listening to them,” he once explained. “And I assume that everyone is smarter about something than I am.”

One day in 1952, a fifty-two-year-old traveling kitchen-product salesman named Ray Kroc walked into a family-operated burger joint in the desert outside Los Angeles—and had a vision of the future of the restaurant business.

What he saw that day in the McDonald brothers’ San Bernardino restaurant—efficiency, cleanliness, fast assembly-line service, value prices, and a simple, short menu—inspired Kroc to buy the brothers out, franchise the concept, and launch the world’s biggest restaurant chain, all based on a product that much of the world is still in love with: the hamburger. Kroc became the founding father of fast food and one of America’s greatest entrepreneurs.

Kroc’s success mirrored the rise of the franchise model of entrepreneurship, in which a small business owner joins a network of branded outlets and shares in their business format and marketing and operations power in exchange for paying a royalty fee. Franchising grew rapidly after World War II and expanded to the restaurant, gas station, print shop, and many other business segments, and by 2010, more than eight million Americans were employed by over 750,000 franchise units.

Many of these pioneers have been immigrants, who have always played a key role in American entrepreneurship ever since the days of people like French-born Stephen Girard, German-born John Jacob Astor, and Scotch-born Andrew Carnegie.

In Boston in 1951, Shanghai-born An Wang started Wang Laboratories with $600 and built it into a $3 billion business employing over 30,000 people before his death in 1990. Palestinian-born Jesse Aweida helped launch the data storage industry when he established Storage Technology in 1969. Hungarian-born Andrew Grove pioneered the semiconductor industry. Russian-born Sergey Brin cofounded Google in a rented garage in 1998. South African–born Elon Musk is transforming the businesses of space, energy, and automobiles.

Today immigrant entrepreneurs are achieving great things across the nation. Immigrants are more than twice as likely to launch a new business as citizens born in the United States. And while immigrants compose some 13 percent of the population, they currently start over 25 percent of new businesses in America.

As just one example, take the story of Asian immigrant Derek Cha. Forty years ago, twelve-year-old Cha came to America with his parents and three siblings. “In 1977, South Korea was a poor country,” Cha recalled. “My parents were looking for better opportunities and education for us.” His father worked as a janitor and dishwasher and his mother as a seamstress. Young Derek helped with his father’s work, delivered newspapers, and at sixteen started his first job, at McDonald’s.

In 2009, after an earlier business failure, and as the economy was recovering from a major recession, Cha launched the Richmond, Virginia–based SweetFrog chain of frozen yogurt shops. Today, the firm has over 340 locations in twenty-seven states and was named a top franchise for veterans by Entrepreneur magazine in 2017.

One of the most amazing American entrepreneurs of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries is a man from Omaha, Nebraska, by the name of Warren Buffett.

He started a company in his bedroom and went on to become the head of a multinational conglomerate, a global rock-star business guru, and one of the wealthiest people on the planet.

The son of a congressman and stockbroker, Buffett showed a keen aptitude for money and business from a very early age, including the striking ability to perform like a human Excel program, rattling columns of numbers off the top of his head.

When he was six years old, Buffett went to his grandpa’s grocery store and bought six-packs of Coke and resold each bottle at a marked-up profit. He devoured a library book called 1000 Ways to Make $1000 and operated a lucrative paper route and a successful pinball machine business in high school. When he was eleven, Buffett bought his first stock, three shares of Cities Service Preferred at $38 per share, but sold them too soon and missed its eventual rise to $200. That experience, and a book about “value investing” he read at age nineteen titled The Intelligent Investor, taught him an important lesson: to invest patiently for long-term growth, not short-term profit.

After attending the University of Nebraska and Columbia Business School, Buffett went to work selling securities for his father’s brokerage company in Omaha for three years. To save money, he and his new wife moved into a modest house and even made a bed for their newborn daughter in a dresser drawer. He was terrified of public speaking. “You can’t believe what I was like if I had to give a talk,” Buffett recalled. “I would throw up.” He took a public speaking course taught at Dale Carnegie, the institute named for the author of How to Win Friends and Influence People, he overcame his fear, and eventually he became one of the world’s most influential business speakers.

In 1956, Warren Buffett decided he was ready to become a full-time American entrepreneur. He launched his own investment company in one of his bedrooms, then moved to a little office with seven limited partners, including his aunt Alice and his sister Doris. His business boomed, and in five years his partnerships achieved a 251 percent profit, while the Dow Jones Industrial Average had increased only 74.3 percent. By 1962 he was a millionaire. That year he invested in troubled textile-manufacturing firm Berkshire Hathaway, which eventually became the parent company for his investment empire, which, despite periodic market downturns, has thrived remarkably over the last half century.

Today, the eighty-eight-year-old Buffett has a net worth of nearly $90 billion. In early 2018 a single share of Berkshire Hathaway stock was selling for $294,000. Buffett still lives in the modest house he bought in 1957 for $31,000, doesn’t use a smartphone, and takes public transportation instead of private jets.

One of the greatest entrepreneurs in American history had a secret life.

He was the James Bond of charity, a mystery man who used a small army of lawyers, executives, and shell organizations to keep his identity totally secret and give away billions of dollars to worthy causes.

For twenty years, he was one of the richest men on earth, but almost no one knew who he was.

Unknown to all but a tiny handful of people, this quiet, humble, mega-rich, self-made man traveled the world on a highly covert mission—to give away almost all the money he made, and to stay completely anonymous.

And he almost got away with it.

Charles Feeney was born in Elizabeth, New Jersey, in 1931, the son of a nurse and an insurance man, and the grandson of Irish immigrants. As a boy, he hustled for jobs, shoveled snow, sold Christmas cards door-to-door, and caddied at golf courses. After serving in Korea in the U.S. Air Force, he attended the Cornell University School of Hotel Administration on the GI Bill.

As a college freshman, Feeney started a sandwich delivery business that serviced his fellow students. He shrewdly bought sandwich ingredients on a Friday with a check that wouldn’t clear until Monday, and got his buddies and roommates to pitch in and make the sandwiches. On weekend nights, when convenient snacks and munchies were scarce and students were hungry, Feeney, known as “the Sandwich Man,” blew a whistle outside fraternities and sororities to announce his arrival. He sold seven hundred sandwiches per week and bankrolled a trip to France.

In Europe, Feeney and his college buddy Robert Miller hit upon the idea of entering the duty-free liquor business and launched a venture that came to be known as DFS, or Duty Free Shoppers. In the late 1950s, reported journalist Mike Colman, “the two Americans began driving from port to port all over Europe, meeting U.S. Navy ships as they docked and taking orders. They expanded their range, adding perfume, watches and cars. There was a mail-order arm and duty-free sales to American tourists driving back over the Canadian border. Almost as an afterthought, they picked up the duty-free concessions at new airport terminals in Honolulu and Hong Kong.” Money rolled in, but it went out just as quickly, and by 1965 the company was so overextended that it faced bankruptcy.

Feeney and his partners reorganized just in time to catch a wave of new global tourist business that took off in 1966 when the Japanese government lifted travel restrictions on its citizens at the same time its economy boomed. This unleashed a massive pent-up demand for gift items like liquor and perfume, which DFS offered duty-free at a fraction of the prices in Japan. Feeney struck deals with tour guides to walk their Japanese tourist groups through DFS airport outlets around the world, which featured Japanese-speaking sales staff. “That’s when the business kind of exploded,” Feeney recalled. “We couldn’t wait on the tables, we had so many customers. That’s when I thought, oh my, this is a good business.” As the first truly global chain of duty-free airport stores, Feeney and his partners quietly created an entirely new business category—and an incredibly profitable one.

It was a license to print hundreds of millions of dollars, and by the 1980s, DFS was a thriving, highly profitable, privately owned multinational company and the largest travel retailer in the world, making Feeney and Miller among the wealthiest people on earth.

Then, at the age of fifty-three, in what journalist Conor O’Clery called “one of the biggest single transfers of wealth in history,” Feeney decided to do something no one else is known to have done before. He decided to give away billions of dollars, nearly all the money he had made, to charity—and to do it in total secrecy.

Chuck Feeney, it turns out, was a frugal, humble man, in the extreme sense of those words. He kept his name out of the media. He was deeply uncomfortable with the trappings of wealth. For decades, he traveled coach, took the New York City subway, wore off-the-rack clothes, held meetings in coffee shops, carried his newspaper in a plastic bag, and wore a Casio watch that cost less than fifteen dollars. He figured, “If I can get a watch for $15 with a five-year battery that keeps perfect time, what am I doing messing around with a Rolex?” On one occasion, Feeney explained simply, “I am not really into money. Some people get their kicks that way. That’s not my style.” Though he was, in his words, an “intensely competitive” businessperson, he explained that in life there has to be “a balance of business, family, and the opportunity to learn and teach.” Feeney has also referred to himself as “the shabby philanthropist” and once noted, “It’s the intelligent thing to be frugal.”

After a brief encounter with Feeney in 2007, New York Times reporter Jim Dwyer described him as an anonymous face in the crowd. “Rumpled by habit, limping on old knees, smiling faintly after a night of celebration, Chuck Feeney stepped out of a building on Park Avenue Monday night and vanished, carried away on a river of passing strangers who knew nothing about him,” Dwyer recounted. “Perfectly disguised as an ordinary man, Mr. Feeney, one of the most generous and secretive philanthropists of modern times, had dropped from sight once again. It is a skill he mastered over decades.”

One of Feeney’s first forays into philanthropy occurred in 1981, when he gave his alma mater Cornell University $700,000. This triggered a flurry of requests for money. Feeney thought about how much of a wider impact he could achieve if he treated philanthropy as a well-managed entrepreneurial and investment venture that selected and screened which causes and charities to support but kept the operation as secret as possible to avoid endless unsolicited pleas for money.

Over and over, Feeney read Andrew Carnegie’s famous 1889 essay “The Gospel of Wealth,” in which the super-tycoon argued not only that a man of wealth should set an example “of modest, unostentatious living, shunning display or extravagance,” but that the best way to deal with wealth was to give it all away, to benefit “the ladders upon which the aspiring can rise,” like libraries and universities. The more Feeney thought about it, he later explained, the more he realized “I did not want money to consume my life.” Unlike Carnegie, though, who widely advertised his giving by name, Feeney would stay anonymous. “I just felt I didn’t see the need for blowing a horn,” he said when asked why he wanted to remain unknown. Family security was another factor. “Part of the consideration was I was married and had five kids. We lived in France at the time. I wanted to make sure that the kids didn’t have security issues.”

Gradually, Feeney came to a life-changing decision. Finally, after making fairly modest provisions for his wife and children, starting in 1982 he transferred all his assets, including his entire 38.75 percent interest in DFS, to a largely secret offshore foundation that eventually was named the Atlantic Philanthropies, dedicated to charitable giving in the United States and the world, especially in the fields of medicine and education. Feeney himself wound up with a personal net worth of less than $5 million. As part of a divorce settlement, his first wife received the family’s seven homes, along with $60 million and funding for her own foundation.

Even Feeney’s business partners did not know of his secret arrangements. For Feeney, it seemed, there would be no building plaques or black-tie dinners in his honor, no publicity machines spreading the word of his good deeds. “Strict rules were formulated for the conduct of the foundation,” wrote O’Clery. “No solicitations would be entertained. Gifts would be made anonymously, and those who received them would not be told where they came from. The recipients, too, would have to sign confidentiality agreements. If they found out anything about the Atlantic Foundation or Chuck Feeney and made it public, the money would stop. The Atlantic Foundation would be the biggest secret foundation of its size in the world.”

For nearly fifteen years, it looked like Feeney would succeed in his covert mission of compassion on a global scale. Between 1994 and 1997, Feeney quietly also used his own personal funds to help broker peace in the northern part of his ancestral homeland of Ireland. Then, in 1997, a multibillion-dollar dispute between Feeney and his business partners over the sale of their company to giant luxury conglomerate LVMH triggered a lawsuit. Feeney knew that by forcing his name into the court system, the astonishing story of his philanthropy would be exposed. His project of secret giving was about to come to an end. So in an effort to preempt and manage the news, he called the New York Times and explained the whole story. After the story ran to the surprise of the business and charity worlds, Feeney receded into the shadows until O’Clery wrote his authorized biography in 2007, The Billionaire Who Wasn’t.

By now, Feeney was in his seventies and his cover had already been blown, so he decided to talk publicly about his legacy on a number of occasions, as a way of encouraging other successful people to adopt a policy of “giving while living.” As Feeney quipped, “It beats giving while you’re dead.”

In 2011, Feeney signed the “Giving Pledge” that was spearheaded by Warren Buffett and Bill Gates, who themselves were acting with the inspiration of both Carnegie and Feeney himself. The pledge calls on America’s wealthiest individuals to promise to give at least half of their wealth to philanthropic and charitable causes. In Feeney’s case it was a retroactively symbolic gesture, since he had already transferred most of his assets to the foundation decades earlier. Bill Gates described Feeney as “the ultimate example of giving while living,” and Warren Buffett said Feeney was the “spiritual leader” for both him and Bill Gates, and that Feeney “should be everybody’s hero.”

By 2020, when the Atlantic Philanthropies is scheduled to cease operations, Feeney and his organizations will have given away almost everything he and his ventures ever earned, a grand total of more than $8 billion. Of that amount, $564 million was used to support the University of California, San Francisco, including a biomedical center and a cardiovascular complex. Additionally, Feeney’s philanthropy helped disadvantaged and vulnerable people, especially youth and the elderly, through medical and education programs in the United States, South Africa, Australia, Ireland, Vietnam, and beyond.

Today, the eighty-seven-year-old Chuck Feeney lives a modest existence in a cramped rented apartment in San Francisco with his second wife, and he still does not own a car. His net worth is said to be less than $2 million.

More than perhaps any other American entrepreneur, Feeney strove to fulfill a challenge that St. Matthew tells us Jesus Christ made in the Sermon on the Mount.

Jesus said that when you give to the needy, “do not let your left hand know what your right hand is doing, so that your giving may be in secret. Then your Father, who sees what may be in secret, may reward you.”

In 2016, a young man in Long Island, New York, wondered about his future.

John Cronin’s high school graduation was coming up, and he figured that he needed to generate some income pretty soon.

He huddled up with his father, Mark, and they chewed over the options.

John adored his father and pretty soon they began talking about starting a business together. They wanted to become American entrepreneurs. But there were a million different business ideas out there, and they weren’t sure which one would work for them. The twenty-one-year-old John had only one nonnegotiable requirement—whatever they did, it had to be fun.

Their first idea was a food truck.

This made sense, John recalled, because “both of us are good at eating.” The trouble was, neither man could cook. They scratched that idea.

For most of his life, John loved wearing wild and crazy socks. His older brothers often asked their father to tone down their kid brother’s wacky hosiery choices. John ignored their pleas. “They are not the fashion police,” he explained. “Socks are fun and creative and colorful, and they let me be me.”

John had another special personality characteristic. As he puts it, “I have Down syndrome and it never holds me back.”

By November 2016, John Cronin and his father settled on a brainstorm idea that John, who studied retailing and customer service in high school, had suggested. They decided to open an online store to sell socks with fun and wacky designs.

Mark thought his son’s idea was great. “Most of us wear some sort of uniform to work—it might be a suit, it might be khakis and a polo shirt, it might be an orange jumpsuit,” he recalled. “Yet you can wear a pair of socks and express yourself, adding some color and flair, and you can do that for $10 or less.” They decided to call the store “John’s Crazy Socks.”

Together they designed a logo and a website. “I came up with a catchphrase,” John said. “Socks, socks, and more socks.” They opened up a “pick-and-pack warehouse,” eventually stocked with a curated collection of over 1,500 variations and designs of socks made by different manufacturers—everything from Abe Lincoln socks to socks featuring beer, astrological signs, and NFL quarterbacks. They launched a social media campaign featuring lots of videos starring John, the company’s cofounder and CHO, or Chief Happiness Officer.

Their first month in business, they sold four hundred pairs of socks. After a little more than a year, they were selling eight hundred pairs of socks every day, had shipped more than 42,000 orders, and hit $1.4 million in revenue. News articles and TV segments profiled the business. Today John’s Crazy Socks has thirty-two employees on the payroll, half of whom have learning disabilities.

The father-son team picked a good business to be in—the global sock market is expected to nearly double by the year 2025. They work hard together, often pulling ten-and eleven-hour days. Their great love for each other makes it easy, though. “I have the perfect partner,” says the father. “It makes me happy because I like helping all the customers and I like working with my dad,” says John.

John serves as the company spokesperson and brand ambassador, and loves acting as “sock wrangler,” which means picking out socks and helping pack and ship them. Mark handles management, accounting, inventory, and human resources. The company takes a very personal approach. “In every box,” explains John, “I put a handwritten note, some candy, and two discount cards for ten percent off.” If an order comes in within driving distance, John frequently makes the delivery himself, knocking on doors and often getting hugs in return.

John sends socks to celebrities like former president George W. Bush and Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau, and if he learns that a leading athlete has been injured, he sends them socks. John also makes monthly selections for the company’s Monday Madness Mystery Bag and Sock of the Month Club. Five percent of profits are earmarked for donation to the Special Olympics. The company plans to expand its social media presence, offer custom-made socks, and start a wholesale line for other small businesses.

Mark says the company has “a social mission and a retail mission, and they’re indivisible.” He explains, “I don’t think it’s enough anymore to just produce a service or produce a product. I think there has to be values attached to that, and we have a model that’s showing that.” The company wants to inspire other businesses to hire more disabled people.

Says John, “We’re spreading happiness. What’s better than that?”

You can measure business success many ways. But if you measure the worth of a business by its ability to create love and happiness, I nominate John and Mark Cronin as true American Superstar Entrepreneurs.

Sometimes, with TV shows like Shark Tank and The Apprentice, and well-known stories like those of Steve Jobs and Bill Gates, it seems like entrepreneurs are the rock stars of the business world.

But you might be surprised to learn that over the last forty years, entrepreneurship has, in fact, taken a big hit in the United States. It’s always been tough to be an entrepreneur—but recent decades have proven especially tough. By some estimates, three out of four venture-backed start-ups fail, over 95 percent of start-ups fall short of their initial projections, only about 30 percent of family businesses successfully pass to the second generation, and only 10 to 12 percent last into the third.

According to Jim Clifton, CEO and president of the Gallup, Inc., polling company, “The U.S. now ranks not first, not second, not third, but twelfth among developed nations in terms of business startup activity.” U.S. Census Bureau data indicates that when measured in terms of start-ups per capita, we are actually behind countries like Denmark, Finland, New Zealand, Sweden, Hungary, Israel, and Italy. Clifton added, “You never see it mentioned in the media, nor hear from a politician that, for the first time in 35 years, American business deaths now outnumber business births.” In 2015, for example, start-ups totaled 414,000, which was, as the Census Bureau reported, “well below the pre–Great Recession average of 524,000 startup firms.” Likely culprits: the lingering effects of the severe economic downturn and a sluggish recovery, and the disruption and severe competitive pressures caused by the rising market power of giant chain stores and websites.

The good news is that entrepreneurship is still alive, and in many ways well, in America.

We still have a highly innovative, competitive economy, which also happens to be the world’s largest. Entrepreneurial growth is picking up from the depths of the Great Recession. New businesses continue to create an average of three million new jobs a year and have been responsible for almost all of the net new job creation in the United States in the last forty years.

A recent study by the Kauffman Foundation suggests that high-potential small firms, which have a disproportionate positive impact on employment and economic growth, are growing especially fast. The foundation’s high-growth-entrepreneurship index, which has followed fast-growing start-up companies since 2005, has bounced back to its prerecession value. Political leaders in Washington, including a president who was himself once an entrepreneur and heir to a family business, are pursuing pro-business policies that hopefully will create conditions for a long-term boost to entrepreneurship.

Interest in entrepreneurship among young people is high, and the United States may be poised for a burst of new entrepreneurs in the near future. “The number of entrepreneurship classes on college campuses has increased by a factor of 20 since 1985, so it’s possible that there are thousands of future startup founders who are currently employees sifting through ideas for their own firm,” reported Derek Thompson of The Atlantic in 2016. “The Millennial generation may be like a dormant volcano of entrepreneurship that will erupt in about a decade.”

As long as there is a United States, there will be American entrepreneurs. “The opportunities for people with ideas and a willingness to take risks are plentiful in America, and there is plenty of capital available to bring those ideas to life,” said historian John Steele Gordon in 2013. “On top of that, mechanisms to bring ideas and capital together are more robust than they have been in the past. So the future of entrepreneurship in this most entrepreneurial of countries remains bright.”

I have discovered the greatest book of business wisdom ever written.

It is the ultimate management book, an ancient guide to life and business that I refer to on a daily basis.

This book contains all the secrets to success, leadership, management, and prosperity in a thrilling collection of inspiring lessons and stories that have endured for thousands of years.

It is the perfect book of guidance for entrepreneurs.

It is called the Holy Bible.

I’ve got a copy of the book in my desk at the office, and I’ll crack it open at the drop of a hat, to seek a joyful moment, a word of comfort, or a burst of wisdom to guide a personal, family, or business decision. Many days, I start off in a moment of prayer and reflection, heeding the challenge of Psalm 5:3: “In the morning, Lord, you hear my voice; in the morning I lay my requests before you and wait expectantly.”

Whether or not someone believes as I do that the Bible is divinely inspired and that Jesus Christ is our savior and the son of God, there is a wealth of magnificent wisdom in the scriptures that can help the American entrepreneur, or anyone else, thrive through risk, danger, and adversity, and master the challenges of failure and success.

I believe that one of the reasons entrepreneurs have made such a powerful contribution to American history is that religion, spirituality, and the Bible are a part of so many of our lives. My family and I have always been connected to faith-based and Bible-based congregations, camps, charities, and volunteer groups, and in doing so we have joined a great American tradition, a bedrock of our democracy and our economy.

Religion itself is a huge American enterprise, and it has a massive impact on American economic life. A 2016 study by the Religious Freedom and Business Foundation estimates that religion contributes about $1.2 trillion of social and economic value annually to the U.S. economy. Of this, about 40 percent comes from religious congregations, the rest from other religious institutions such as universities, health systems, and charities, and from faith-inspired, faith-related, or faith-based businesses.

There are more than 344,000 religious congregations in America, including churches, chapels, temples, synagogues, and mosques. They buy billions of dollars of goods and services, often from local and small-town American entrepreneurs, and hire hundreds of thousands of American workers, both full-time and part-time. Schools that are connected to congregations educate 4.5 million students and have 420,000 full-time teachers on the payroll every year.

Religious congregations and faith-based schools have a long-term multiplier effect for America, too. The impact of faith-based schools in the United States is significant. For instance, St. Benedict’s Prep in Newark, New Jersey, gets 530 largely minority and economically disadvantaged boys ready for their college and career journeys, and has a good record of college graduation and alumni achievement. One graduate, Uriel Burwell, came back to the community and launched an affordable housing campaign that raised $3 million and built dozens of affordable homes. Religiously inspired institutions are key players in the world of higher learning, like Jewish-affiliated Brandeis University, my alma mater of Christian-inspired Harding University, Catholic University, Liberty University, and many, many others.

Religious congregations support local and community nonreligious groups doing great work, from the American Red Cross and the United Way to Big Brothers and Big Sisters. The evangelical Christian mega-congregation of Saddleback Church in Orange County, California, has helped tens of thousands of citizens get back on track with church-hosted alcohol recovery programs. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has set up employment service centers across the nation. One in six hospital patients in America is cared for in a Catholic facility. Adventist Health System has forty-six hospitals and employs over 78,000 people. Over 25,000 American congregations conduct active ministry to help folks coping with HIV/AIDS. Catholic groups like the Knights of Columbus and Catholic Charities address a wide range of human needs with hundreds of thousands of volunteers and multimillion-dollar budgets, as do charities inspired by many other faiths.

The net effect of all this great work is to make America a better and stronger nation, and to help create the conditions where entrepreneurs and everybody else will thrive.

Beyond all this good work and economic impact, religion is a guiding source of life inspiration for multitudes of American entrepreneurs. Consider, for example, the writings referred to by Christians as the “Old Testament” and the “Hebrew Scriptures” by the Jewish faith, and the writings that Christians call the “New Testament.” These writings have many parallels in other world religions, too. They contain an amazing collection of prayers, devotions, parables and encouragements, gentle reminders and commandments, all of which are relevant not only to daily life, marriage, and parenthood, but to business as well. As 1 Timothy 6:12 challenges us, “Fight the good fight of the faith. Take hold of the eternal life to which you were called when you made your good confession in the presence of many witnesses.”

One day not long ago, as I read the Bible from front to back, I realized to my surprise that both testaments contain a pattern of five great insights that you can call “the Entrepreneur’s Code”—Wisdom, Courage, Compassion, Integrity, and Humility. These insights, I realized, have spoken directly over the years to everything I’ve experienced in business being an American entrepreneur.

The first insight in the Entrepreneur’s Code is Wisdom.

Our business and personal lives are a journey in search of wisdom into ourselves and the world around us. As Proverbs 7:4 commands us, “Say to wisdom, ‘You are my sister’; and to insight, ‘You are my relative.’” And for me, the best source of wisdom is that contained in the Bible, which many of us believe is divine wisdom communicated to us in the voice of ancient prophets. As Job 12:12 says, “Is not wisdom found among the aged? Does not long life bring understanding?”

In many Bible passages, such as Proverbs 4:5–9, you can find a road map of inspiration to achieve the wisdom necessary for success in both life and business:

Get wisdom, get understanding;

do not forget my words or turn away from them.

Do not forsake wisdom, and she will protect you;

love her, and she will watch over you.

The beginning of wisdom is this: Get wisdom.

Though it cost all you have, get understanding.

Cherish her, and she will exalt you;

embrace her, and she will honor you.

She will give you a garland to grace your head

and present you with a glorious crown.

The second insight of the Entrepreneur’s Code is Courage.

To succeed as an entrepreneur, you must marshal your courage, embrace risk, and be ready to push through the inevitable trials and storms of business, with boldness and diligence. This includes the courage to take action and work very hard. In the words of Proverbs 28:1, “The righteous are as bold as a lion.”

In my own career, I feel that these biblical encouragements toward courage and diligence have helped me tremendously. “The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom,” proclaims Psalm 111:10 in a passage that helps form the foundation of my life’s mission; “all who follow his precepts have good understanding.”

As Ecclesiastes 9:10 puts it, “Whatsoever your hand finds to do, do it with all your might,” and in the words of Proverbs 22:29, “Do you see someone skilled in their work? They will serve before kings.” And as Galatians 6:7 cautions, “A man reaps what he sows.” The way of the entrepreneur is often the path of those who outhustle, outthink, and simply outwork the competition. “By the sweat of your brow you will eat your food,” declares Genesis 3:19.

I’ve never had the pleasure of “standing before kings,” or queens, for that matter, but I have spent some quality time with the last two presidents of the United States!

The third insight of the Entrepreneur’s Code is Compassion.

If you make compassion your personal and business goal, I believe you can move mountains and achieve miracles, as well as have material success. Compassion, to me, means showing mercy, love, understanding, and positive actions to your family, your coworkers, your employees and partners, your customers, people in the community who are in trouble or disadvantaged, even your competitors.

In the words of Proverbs 20:28, “Love and faithfulness keep a king safe; through love his throne is made secure.” And as Proverbs 10:12 puts it, “Hatred stirs up conflict, but love covers over all wrongs.” Job 27:4 declares, “My lips will not say anything wicked, and my tongue will not utter lies.”

You don’t see too many business books written about love, but I think it’s the entrepreneur’s secret weapon. Many of America’s great entrepreneurs were motivated at one time or another by authentic love—for innovations that helped the world, for their family, their employees and customers, and for the millions of people who would benefit from their philanthropic work. As 1 Corinthians 13 declares,

If I speak in the tongues of men or of angels, but do not have love, I am only a resounding gong or a clanging cymbal . . . Love is patient, love is kind. It does not envy, it does not boast, it is not proud. It does not dishonor others, it is not self-seeking, it is not easily angered, it keeps no record of wrongs. Love does not delight in evil but rejoices with the truth. It always protects, always trusts, always hopes, always perseveres. Love never fails.

Throughout our history, American entrepreneurs like Stephen Girard, Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, Chuck Feeney, and countless others have heeded the words of Psalm 112:9: “They have freely scattered their gifts to the poor, their righteousness endures forever.”

The Bible actually promises us, in Proverbs 3:3–10, that if you guide your life by love, mercy, and truth, and place your honor and trust in God, “you will win favor and a good name in the sight of God and man,” “he will make your paths straight,” you will “bring health to your body and nourishment to your bones,” and “your barns will be filled to overflowing, and your vats will brim over with new wine.”

The power of compassion and charity extends to the ways we entrepreneurs manage our employees and team members. Proverbs 3:27 proclaims, “Do not withhold good from those to whom it is due, when it is in your power to act.” Proverbs 27:23 urges us to “be sure you know the condition of your flocks, give careful attention to your herds.”

The Bible is filled with sayings that I see as encouragements for us to show leadership through positive reinforcement, supportiveness, and recognizing and complimenting our staff, such as Proverbs 16:24, “Gracious words are a honeycomb, sweet to the soul and healing to the bones,” and Proverbs 17:22, “A cheerful heart is good medicine, but a crushed spirit dries up the bones.”

The Bible also urges us to control our anger, which is excellent advice for the entrepreneur in dealing with rough-and-tumble decisions, crises, and employees. “Do not be quickly provoked in your spirit,” says Ecclesiastes 7:9, “for anger resides in the lap of fools.” Proverbs 21:23 points out that “those who guard their mouths and their tongues keep themselves from calamity.” And likewise, Proverbs 14:29 and 16:32 point out that “whoever is patient has great understanding, but one who is quick-tempered displays folly”; and “better a patient person than a warrior, one with self-control than one who takes a city.”

The fourth insight in the Entrepreneur’s Code is Integrity, which to me means being honest and righteous with the world, including the world of business.

Integrity, honesty, and fair dealings come up again and again in the Bible. Leviticus 19:13 reads, “Do not defraud or rob your neighbor. Do not hold back the wages of a hired worker overnight.” Psalm 25:21 challenges us, “May integrity and uprightness protect me, because my hope, Lord, is in you.” Job 27:5 includes the resolute phrase “till I die, I will not deny my integrity.” Proverbs 11:1 declares, “The Lord detests dishonest scales, but accurate weights find favor with him.”

As Isaiah 33:15–16 puts it, “Those who walk righteously and speak what is right, who reject gain from extortion and keep their hands from accepting bribes . . . they are the ones who will dwell on the heights, whose refuge will be the mountain fortress. Their bread will be supplied, and water will not fail them.”

I believe that integrity as an entrepreneur also means being honest with your employees and business partners, and constructively and respectfully pointing out their mistakes and areas of improvement as a way of helping them. Proverbs 25:12 tells us, “Like an earring of gold or an ornament of fine gold is the rebuke of a wise judge to a listening ear.”

The final insight in the Entrepreneur’s Code is Humility.

This means being honest with yourself—admitting your weaknesses and limitations, and reaching out for help when you need it.

The Bible tells us that we must seek out the advice and opinions of others. As Proverbs 11:14 advises, “For lack of guidance a nation falls, but victory is won through many advisers.”

We must also acknowledge our mistakes, and, as hard as it is, welcome and even seek out criticism. “The purposes of a person’s heart are deep waters,” reads Proverbs 20:5, “but one who has insight draws them out.”

As an entrepreneur, a father, and a husband, I make mistakes on a fairly regular basis, but the words of the Bible teach me that it’s my responsibility to learn from them and try not to repeat them. The entrepreneur needs to understand that, in the words of Proverbs 6:23, “correction and instruction are the way to life.”

“Teach me, and I will be quiet; show me where I have been wrong,” reads Job 6:24, “and cause me to understand wherein I have erred.” As Ecclesiastes 7:5 points out, “It is better to heed the rebuke of a wise person than to listen to the song of fools.”

In 1925, an entrepreneur named Bruce Barton wrote a book that became one of the bestselling books of the twentieth century.

Titled The Man Nobody Knows, it told the story of Jesus Christ, a young religious leader who “picked up twelve men from the bottom ranks of business and forged them into an organization that conquered the world,” and in only three years, defined a mission, carried it out, and launched the most successful start-up in human history.

Barton, who cofounded a company later known as BBDO, which today is one of the largest advertising agencies in the world, saw Jesus as a strong, tough, decisive, and charismatic leader who chopped wood and swung an ax as a successful carpenter, who “slept outdoors and spent his days walking around his favorite lake,” and whose “muscles were so strong that when he drove the money-changers out, nobody dared to oppose him.” In fact, Barton saw Jesus as nothing less than “the founder of modern business.”

In the midst of the Roaring Twenties, when the United States was enjoying a dizzying economic boom and social mores were changing rapidly, Barton’s book struck a powerful chord. Barton wrote that Jesus was a model of leadership in any age. “First of all he had the voice and manner of the leader—the personal magnetism which begets loyalty and commands respect.” He wrote, “The essential element in personal magnetism is a consuming sincerity—an overwhelming faith in the importance of the work one has to do . . . that quality of conviction.” Jesus was a superb organizer, communicator, and motivator, and the ultimate “servant-leader” who led by the inspiration of his personal example. In one extreme act of humility, Jesus went so far as to wash the feet of his own disciples.

All his leadership qualities, noted Barton, helped Jesus forge a motley collection of followers into a world-changing vanguard of inspiration whose influence is felt centuries later in the lives of billions of people. The original group of his followers, Barton pointed out, featured “[n]obody who had ever made a success of anything, a haphazard collection of fishermen and small-town businessmen, and one tax collector—a member of the most hated element in the community. What a crowd!”

With that bunch of misfits, losers, and sinners, Jesus changed the destiny of the human race for the better. If ever there was a person who personified the qualities of Wisdom, Courage, Compassion, Integrity, and Humility, He was it.

As I look back at the history of American entrepreneurs both big and small, I have come to realize that, above all, these are the qualities that will help us persevere through trials and tribulations, to weather the storms of failure, chaos, and uncertainty, and to achieve success in our business and personal lives.

These are the secrets that will truly help us build a golden age of success for ourselves, our families, and our fellow human beings.

I believe in the Lord. I believe He has set up you and me for success. And I believe that if we remain true to our vision of a better life for our families and community, He will come through for us when times are the toughest.

One day a number of years ago, when our family business was in its early years, we ran out of money.

We had run out of credit. We had literally nothing in the bank, but an $800 banknote was due. My father was at the end of his financial rope, totally out of ideas, and my mother was in tears of despair, seeing the whole future of what we had scraped and built together as a family come crashing to an end.

My father said, “Well, I might as well go down to the mailbox and see if anybody’s sent us any checks.”

My mother replied, “There are no checks due! We’ve deposited and spent all the money we’re due for every order we’ve gotten!” He went to the mailbox anyway.

When he opened up the mailbox, he found an envelope in there that had a whole lot of international postage on it.

It was a letter all the way from Japan, and enclosed was a check for exactly $800 to prepay for a bulk shipment of duck calls.

Now, I don’t remember any orders from Japan before then, and I don’t remember too many at all since then, but this was for real. The check cleared, and we were able to make our bank payment.

That envelope saved our family business. The postmark may have been from Japan, but I think it really came from an address far, far above us.

The Lord truly does work in mysterious and beautiful ways. He certainly has for this American entrepreneur and his family.

As you experience the struggles and joys of your own business and career, I pray that He will do the same for you, too.