IN THE PROFESSION OF HORTICULTURE, pest-control philosophy has changed greatly since the widespread successes of Integrated Pest Management (IPM), introduced in the late 1960s. IPM promotes minimization of problems through observation, early intervention, and less toxic, disruptive methods. Though it took twenty years, nurseries, botanical gardens, and classrooms have mostly adopted IPM and reduced—but not eliminated—wasteful, rote, calendar-based spray programs. But in home gardening, we’ve gone the wrong way, letting pesticides become more common and easier to use, while glossing over the environmental, health, and financial costs. In some home gardens, seasonal weed and insect sprays have become much more common than they were a few decades ago.

Misleading marketing and public policy lulled us into a comfortable numbness. It can be all too easy to believe that there are people in our government, some benevolent “they,” that wouldn’t let things be sold that are really harmful. During the same time, pests have also changed. New pests have moved into new areas, and as we eliminate one pest, we create whole new problems. That was just the case with screwworm flies, parasites that used to kill warm-blooded animals; their larvae would bore into the animals’ hearts. It was a huge problem for everyone who had a cow or goat, but the flies also attacked deer. In the 1950s, a program designed to save cattle and goats eradicated screwworm flies but unintentionally resulted in the explosion of the deer population throughout the country.

An old gardeners trick is to plant marigolds among other plants for protection from parasitic microorganisms in the soil. This simple pairing represents complex relationships in the soil.

What is a pest? There’s such beauty in the insect world and so many connections that we must learn to consider. Trying to kill one pest might kill something like these beautiful flatid bugs in Madagascar.

Our expectations changed, too. Magazines and social media now show digitally altered photos of gardens, encouraging us to long for and buy things that promise perfection, even though our hobby of gardening is often done to reconnect us with the natural and somewhat messy world. No matter when or where, pest control through domination is expensive. Our recent understanding of soil microbiology has only just begun to show us how damaging pest control is to beneficial bacteria, fungi, and insects belowground. We now have entire industries seeking ways to address the unanticipated consequences of pesticides.

Beaver damage around the pond upstream from your house may indeed be a problem, but in the Congaree National Park in South Carolina, the beavers have stripped the bark off the trees to reveal the stunning pattern of borer holes.

To some degree with food crops, we’ve accepted that blemishes or bug holes are okay and may even indicate a more organic, toxin-free, safer fruit or vegetable. But when it comes to garden plants, we’ve gone the opposite way. We expect every plant to be blemish free; full of glossy leaves, symmetrically formed and already budded. Consider this change: just twenty-five years ago, you visit a nursery, where the family who ran it would work with you to help you pick out a good plant. Today, most people buy plants in a box store, from a sales clerk who rotates through the garden center, the Christmas-tree center, and the paint or lumber section. Every plant, therefore, must be tolerant of varied care and must have very broad appeal to attract a range of plant buyers. The nursery producing that plant aims for a pretty face. I think it’s time for us, as gardeners, to remember that perfection in pots isn’t our goal. It’s time we recognize that a blemished rhododendron, like a tomato with a spot, may be a great plant that came from a producer who’s watching and treating with pesticides only when needed.

All of this begs the question, what is a pest? From a holistic perspective, everything is a sort of pest to something else—even us—but some more so than others. So when do we decide that a pest requires some kind of intervention? My philosophy is that when a pest seriously threatens my family or myself, and the crops that support us, I intervene. But my first and daily responsibility is to make sure I do all I can to prevent problems before they get out of hand. Rust on crinum leaves, vole nibbles on the roots, and black spot on roses do not count. It’s part of my job as a bulb farmer to help my clients and customers understand that plenty of healthy plants have pest damage. A bite out of a leaf or a dusting of sooty mold isn’t much different from a liver spot on your skin. One of the grand dames of southern horticulture, Miss Hattie Watson, preached the live-and-let-live philosophy for over sixty-five years. Of most pests, including mildew on phlox, Miss Hattie recommends one of three options: pretend not to see it, pretend not to care, or go dig around your house to realize that you’ll likely find more little whiskers of fungus on a pair of sneakers in the back of a closest, and focus on that. The takeaway here is that if you put things into a larger perspective, there’s just no need for stress or toxic intervention in gardening.

The Teachers

MISS HATTIE WATSON AND KARI WHITLEY CROLLEY

Miss Hattie Watson and Kari Whitley Crolley are two experts who speak the same language. Miss Hattie’s wisdom comes from years of intuitive experience and gardening at home; Kari’s from science labs at the University of Georgia, breaking through stereotypes, and from running her own company. Both have roles as teachers, leading others to more successful gardens, and both espouse a commonsense, easy way of dealing with pests: live and let live.

Miss Hattie is the kind of person everybody in town thinks they know personally. She shared her garden wisdom weekly for forty years in a local newspaper column, through horticulture groups, and with her friends. She hosted garden open-garden days in Woodlanders Nursery, a world-renowned nursery in Aiken, South Carolina. She learned her craft from seventy years of dirty hands-on gardening: no schools, classes, or symposia. Miss Hattie once told me, “I had the bug. Always have, and you do, too. I can tell. There’s just nothing to do about it is there? You do it because you’re compelled to.”

I also felt like I knew her in some deep, mystical kind of way well before the day we finally met in her room at Aiken’s Lutheran Home. In that first meeting, she’s sharp and intuitive, and we have a great time arguing over whether crinum foliage is too messy for the perennial border. She says, “It’s just like a teenager’s bedroom, you tidy it up one day, then …” the thought trailing off before she can finish. Organizing sentences wasn’t easy for her that day; the effect of a small stroke frustrates her. Still, Miss Hattie is elegant and forthright and anxious to read a new gardening book. She keeps saying to another guest, “I know this boy,” by which she means me. I don’t think it’s the stroke, this time; somehow, I know what she means. She knows me—my motivations, my loves, my passion for gardening, and my soul.

In talking, we discover that we have many connections—small-world, country stuff. She grew up in the swamp right next to where my grandmother grew up; she was a flower girl in my great aunt’s wedding in 1932 or so; we both love the swamp plants. The names aren’t coming to her, but I can guess her favorite ferns, vines, and spring ephemerals. When she says, “Oh, the little white, comes up at Mother’s Day,” I know she means atamasco lily (Zephyranthes atamasco), which carpets the forest floor after spring floods.

I can quickly tell something else about her, too. Though she shares her wisdom and love of plants with every gardener in town that may have met her, Miss Hattie must have lived a somewhat reclusive life. I’m sure that lots of people would balk at my assessment; how could I say that about a local garden legend? But it’s a feeling, and it’s based on a few facts: she gardened enough to teach herself to do it like a pro; she made many beautiful sketches and watercolors of plants in her garden and in the woods; she wrote a lot, by hand and eloquently; and she loved the swamp and her famously jungle-like garden. These are all very solitary pursuits, and ones that I share.

I love a jungly garden, a place for plants. I want to see gardens where plants take control, get comfortable, let down their hair, lie across the walkways, and lean up against each other just being marvelous. I want gardens where the human touch is unseen—but not absent, of course; otherwise it wouldn’t be a garden. Part of gardening this way means wrapping your arms and mind around everything, around the whole—and sometimes the whole includes bugs that suck and smell; hairy, sickly yellow funguses that squish between your toes; rodents that eat every root; even a stroke that keeps you from elegantly organizing.

There’s no need for me to even ask; I know Miss Hattie gardened without trying to kill things. They were a part of her; she was a part of them. I’m not saying she was a Buddhist or anything; I’m sure she dealt with her share of pansy-eating rabbits and hosta-licking slugs. She even told me about how once she and her mother tried to trap an alligator. But when I asked, she couldn’t name one chemical, one bottled pest control that she found necessary in her garden.

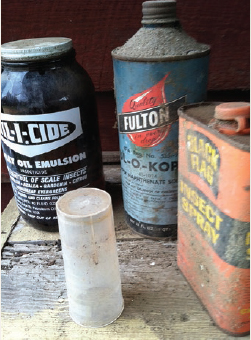

After I finish describing my father’s tool shed, Miss Hattie tells me that she had one like it, too; full of brown, glass bottles with yellow, red, and black labels. Skulls and crossbones, sickening odors, and thick caustic liquids lined shelves in many tool sheds not too long ago. Dust and dusters, things borrowed from the local farmer, would sit for decades in my father’s shed. They seemed like a good idea, but were too unpleasant to use more than once. Common sense kept him from throwing them away—he knew they’d do more damage in the trash—so they all just sat there, sort of safe, in glass bottles with disintegrating labels.

The first question most non-gardeners ask Miss Hattie is about what they can plant and where. But the second, unsurprisingly to me, is about what they can use to kill a certain weed, bug, or mushroom. There is this urge in all of us to be in control. Today, pesticides are marketed to us as silver bullets: easy, bottled solutions that even smell nice. Cool labels promise butterflies and bounty. Sometimes they’re really difficult to resist, but sometimes I go into a garden center and see shelves and shelves of bottled solutions and think, “When did gardening start requiring us to buy all these plastic bottles of stuff?” It doesn’t. The best pest philosophy for gardening, for our health, the health of our plants, and for all the little creatures and connections that we’ll never quite explain, is to live and let live.

In gardens we make along waterways, such as this marshside garden, it’s easy to understand how fertilizers and pesticides will run through the ground into the water. The same is true, while less easy to see, for any garden.

Weeks later, I’m sitting with plant pathologist Kari Whitley Crolley, looking out over that swamp that Miss Hattie loves. Kari is a super-cool woman who runs her own Integrated Pest Management business, serving farms and wholesale nurseries all over the Southeast. She also serves as a board member of Charleston Horticultural Society and the South Carolina Nursery Association, and she teaches horticulture. I’ve seen Kari win over a conference hall full of really experienced landscape guys by issuing an opening statement that makes them look around wide-eyed and poke each other like a bunch of schoolboys challenged by a girl: “I know more about pesticides than anybody else in this room.” Kari has studied pesticides from the historical, chemical, human genetics, cultural, and even advertising standpoint. She’s worked on nurseries that have used masses of pesticides and, subsequently, has deeply considered the impact on both her own body and the health of future generations. She knows the ways that pesticides work, how they kill, and she knows a lot about the unintended consequences of their use and misuse.

Kari asserts, “Pesticides totally, completely changed how we live. We couldn’t live this way, in America, in any sense, without them.” She means that in every way. She and I couldn’t sit overlooking this marsh. We couldn’t have had a glass of wine, while we picked some tomatoes from the garden. We couldn’t turn on the tap for clean water to boil our pasta. We couldn’t have the wheat used to make the pasta or the paper for the pasta box. We couldn’t have “tamed” and populated this wild, buggy country.

The impact of pesticides is positive and negative: on the health of our water supply, insects, our crop pollination, our soil and rivers, and our bodies. We want commerce, industry, and agriculture, which rely on pesticides, but we don’t have a clue how those pesticides really affect us—the good ways are out of sight and mind; the bad ways may simply be unknown.

Kari’s business is called Scout Horticultural Consulting. For homeowners, she’ll investigate odd pest issues, look for underlying causes, and make recommendations for changes. She’s like a crime-scene investigator for plant problems. I’ve watched her work, snooping around the base of a bay laurel hedge that for no obvious reason gets galls and canker on the stems. She takes samples and sends them off to labs, punches the screen on her phone, makes calls, and interviews everyone who might have taken a leak behind the hedge. A few days later, she presents a full-color, PDF report of all the issues that she has identified along with a few, commonsense solutions. The report begins:

This is a very long report for a short diagnosis. I think that as a combination of initial improper planting depth and poor pruning, along with the hot, humid summers (not to forget the carbohydrate-robbing high night temperatures) and irregular cold patterns in the winter, these plants have been very stressed. I checked many galls and cankers for fungal spores. Even after seven days in a moisture chamber (to coax spore production), no pathogenic fungi were detected. Secondary (opportunistic) fungi were detected in some samples.

Even along rural waterways, homes, and golf courses, agriculture and industry nearby use pesticides and pollutants that flow into our rivers. The Edisto River in South Carolina is the longest undammed, blackwater river in the country. Here it looks pristine, but toxins in the water accumulate and poison the fish, as evidenced by signs warning against eating from the river.

You see how thorough she is? For home gardens, for giant nurseries, or for farmers, Kari investigates pest problems, scouts farms on a regular basis to preempt problems, and recommends pesticide and non-pesticide solutions. She has the right to boast:

I tell all of my classes that I know more about pesticides than any one person they are going to meet. I know them from a huge, wholesale nursery perspective, from a farm perspective, from a home landscape and garden perspective, from a biochemical perspective. I know the actions they take to kill things. And I tell them that based on that, I know that home gardeners have no need and no business using anything. That is a powerful statement.

I am thoroughly educated in regard to pesticides, and I don’t own or use pesticides at my home. It’s ironic that in an attempt to garden and be as close to nature as possible through the cultivation of the earth, that you would be willing to apply toxic pesticides to create your personal Eden. It shows how incredibly detached we’ve become from nature and how little we understand its complexity.

This is certainly a lot to ask of a modern home gardener, but it’s the way Miss Hattie gardened. Some things die, other things thrive. It’s a gardening philosophy that respects all life in the cycle. Even if you just stop using them, there are still enough pesticides in the world that our bodies and gardens are filled with them. Just like we don’t use or need algaecides to add to a glass of water, we don’t need pesticides to add to our garden. They are already there. There is no stopping the seep, through water, soil, and air, without huge societal and political changes. Even if you never buy one bottle, you bring the stuff in: when you buy a plant, when you buy a truckload of mulch, and when you buy a bale of hay. Lots of “ornamental” vegetables are sold potted in soil treated with a chemical that keeps them compact. These chemicals can have residual effects in the soil. When you remove that plant and put something else in, it too may be dwarfed. And be aware that plants sold as ornamentals, even if they are traditionally edible, may be treated with chemicals not allowed for food crops. A broader problem can come with mulch or compost containing chemicals.

Just a few years ago, uninvited pesticides killed hundreds of vegetable gardens across North America and Europe. It started with hay farmers spraying a new broadleaf pesticide on their grass fields. This pesticide targets non-grassy plants, so it can be applied over pastures. The pasture grasses absorb it without injury, while the weeds with broad, rounded leaves die. For government approval of this new product, the company said it would last in the soil about ninety days, then break down to inert chemicals. The EPA agreed. The treated pastures eventually became hay that got cut, baled, shipped as mulch, and fed to animals. According to how it was presented to the EPA, that’s where it should have ended. But things have unfolded very differently: animals passed it through, companies made compost from it, sold bags of that compost, and in a few years, vegetable gardens died. The residual life of that pesticide (aminopyralid), applied many miles away, transferred to those home gardens. Research from major universities has demonstrated that not only does the pesticide last up to seven years, it is transferred in cut hay to any gardener who uses that hay as mulch. Peas and peppers in backyard gardens shriveled in what became known as killer compost. This isn’t an isolated problem; it’s occurring all through the United States and in parts of Europe. The EPA is evaluating this, but meanwhile the pesticide is still in use. To buy hay for our crinum farm, we now have to find farmers, meet with them, and ask the right questions before we buy. For your home garden, look for a seal from the US Compost Council or use non-manure compost.

Pesticides come on the plants you buy, too. Almost every plant you buy from a nursery, unless it’s a nursery that produces its own plants for on-site sales, has been drenched with an insecticide the day it leaves the nursery or has it incorporated into the soil, depending on the way each nursery is regulated.

Kaolin clay is mixed with water and sprayed on these grape leaves, forming a barrier. This is a sort of exclusions of pests that protects the grapes but doesn’t harm the bees. Kaolin is an extremely fine-textured clay mined in South Carolina.

If you’re using a landscape or lawn company, ask questions so that you know what they’re using—or tell them what you want. Home gardeners account for less than 10 percent of all pesticide use in the United States. However, according to the EPA, that 10 percent means that we use about 66 million pounds each year. That huge number includes only what we buy off the shelves, and not the 90 million pounds that landscape companies apply to home and business landscapes. Some estimates break this down to about 6 pounds per acre—3 times the rate that farmers use. And that doesn’t include those used in your park, the grocery store parking lot, the golf course, or the amusement park. If your neighbor, in the broadest sense of the word, is spraying, you’re probably getting some of it. You cannot avoid the seep or the spray from down the street.

How did we get ourselves into this bizarre predicament where cow poop now has to be labeled as toxic? Where manure, spread on fields, gardens, and for renovation of woodlands, might kill garden and wild plants? Where pesticide residue is in our rivers, our food, and our bodies? It started with an agricultural industry that allowed itself to become too dependent on the massive application of chemicals provided by a few massive corporations. The horticulture trade has always followed and been influenced by agriculture. I’m a horticulturist from a family that’s farmed along the same river since the 1750s. They and I see our professions as honorable; we have the knowledge and desire to use the earth to nourish people’s bodies and souls. But the professions have changed. Individual cultivators quit asking questions and agricultural and horticultural societies quit meeting to discuss issues of the day. Agriculture affects every single aspect of life, and we need to be involved, to study, to discuss, and to educate ourselves and our children, especially in areas related to pesticide use, and to be a part of the decision-making process. This is equally important not only in agriculture, but also in the golf courses you walk across or the cut flowers you bring into your kitchen.

Old-style pesticide containers were less friendly, less promising than modern versions.

Ironically, I believe one of the causes for our current trust in the safety of pesticides results from the changes in chemicals brought about by Rachel Carson’s classic environmentalist screed Silent Spring. When this marine biologist and conservationist pointed out the serious problems of the unregulated use of persistent, metal-based compounds, the public outcry forced regulatory changes. Chemicals were also changed drastically. Soon pesticides really were made more safely. We relaxed. Chemical buildups in streams and breast milk began to reduce. Surely, the new chemicals were okay? This is that lull I mentioned earlier; we began to assume that the pretty bottles for sale at the corner store couldn’t be dangerous, simply because they were there. After all of this commotion, all of this debate, they just had to be safe. Didn’t they?

Pesticides kill things. It’s right there in the name; Kari likes to repeat a list of words—homicide, genocide, suicide, insecticide, fungicide, herbicide—to make the point that -cides kill things, often indiscriminately. Besides that, we have an unimaginable number of chemicals now available, by some counts 400,000. Many are less damaging than those that we used to rely on, the pre–Silent Spring ones, but only less damaging. Many combine inside our bodies, in our soil and water, in ways that go unstudied. Even when there were no synthetic pesticides, pest treatments were dangerous. Bordeaux mixture, used for centuries, is still promoted as an organic fungal control for late blight on potatoes, and it moves through the soil to accumulate in streams. It even has its own respiratory disease associated with it, “vineyard sprayer’s lung.” Rotenone, a common organic pest control, is highly dangerous to health and linked to Parkinson’s disease. Pesticides kill.

But our recognition that pesticides kill has diminished. Modern marketing is a huge part of that, but we’re all complicit for not asking enough questions. Remember those old chemical shelves in your parent’s garage? Until the late 1960s, pesticides came in ominous bottles, with unpleasant smells and names. But many people back then were still tied to their rural backgrounds and understood the serious risk of pesticides and the importance of proper handling. Today, chemicals are too pretty, too easy, and too promising, and their instructions and warning labels are too small. We succumb to marketing. Someone understands our dream, or helps create that dream, and then sells us something to achieve it.

In reality, pesticides don’t help achieve many of our dreams. The Worldwatch Institute indicates that for all crops, while pesticide use increased tenfold between the 1940s and the 1990s, plant losses due to pests also increased from a rate of 30 percent up to the current rate of 37 percent. In other words, things didn’t get any better. If home gardening follows trends in agriculture, as it usually does, it’s safe to say that in our gardens, there are no less pests, no more perfect gardens; in fact, there are likely no positive changes at all since we started using pesticides. If you’re not sold on the rational arguments from people like Kari who’ve done the research, who’ve studied this, ask yourself: if pesticides do no discernable long-term good, why are we using them? Why are we gambling with our health, and the health of our planet? The difference between what we dream and what we run into outside too often becomes a frustration. We seek answers believing that someone has them. Every now and then they do, but the cost of the solution is too dear.

Updates and Adaptations

In the early 1980s, I arranged a booth representing the Clemson Horticulture Club. From it, we distributed apples and flyers diagraming pesticide accumulation in apples, which led to my being reprimanded by a professor from our department, even though I knew that this man understood that almost all apples contain pesticide residue. Since then, I’ve strayed in and out of thinking about and using all sorts of chemical pesticides. A few years ago, I finally quit them, at least in my own domain. On our crinum farm, we have complete control and I can be a bit of a purist when it comes to chemicals. Some people have countered that crinum don’t have any serious pests, to which I respond, wasn’t that a smart decision to grow them, then?

As gardeners and homeowners, we need to make good decisions like that. We need to quit wanting to grow the thing that is constantly covered in scale, for one example, but the answer isn’t always quite that simple. Among our crinum, we grow our own food, too. We’ve made difficult choices. For example, we quit growing yellow squash because over the past few years, vine borers have made it impossible to grow without pesticides. In the meantime, we’ve discovered new squash, and we’ve learned how to cook with gourds.

Our crinum fields have been farmed for hundreds of years by lots of different people. Today we’re moving back toward being a polyculture farm with varied crops and animals. Fennel is used to break up the soil, and it attracts a huge variety of beneficial insects.

For the larger populace, changing eating habits is surely more difficult and requires consideration and planning. But it can be done. As hard as it might be to believe, there was a time here in the United States when no one ate pasta. Once the Department of Agriculture decided that it wanted to help farmers sell more wheat, they came up with a plan to promote pasta consumption: macaroni and cheese! Our love of that American staple started with a government marketing program. Nevertheless, changing food crops can be difficult. But Kari says changing garden and landscape crops should not be. From her years in nursery work, she’s concluded, “We as an industry don’t have any business selling plants that cannot thrive without the use of these products. If I had a plant that needed a fungicide in order to survive, I’d rip it out.”

Sometimes it can be really difficult to make the call on how to deal with a pest problem. And although I do believe it’s the same ethical choice—to kill any pest is to kill—it’s more pronounced and dramatic with larger animals. Shoot a deer? Slam a vole with a croquet mallet? Trap a goose? My philosophy is that when we start interfering with nature, we have to deal with, or accept, the unintended consequences. We create pests by living in, developing, and interfering with a huge forest. We like what the forest provides, but we don’t like to share it.

On our farm, our most serious mammal problem is adorable armadillos. We do our best to share with them, even though they present a serious threat to my family. As one plows through the crinum fields and yard, following the same path every night, he digs conical holes perfectly sized to break a person’s ankle. With his nose in the ground, he rumbles between the pink lilies and the deep reds, crunching little grubs and mahogany-colored centipedes. His moonlit circuit returns him to a den with his brothers from dawn to dusk for sleep. Armadillos live in shallow burrows with friends of the same sex. Mothers will give birth to four or so identical young, either all brothers or sisters. After the young finish nursing, they move out to live in single-sex burrows. I think this is kind of sweet: fraternal, monkish.

Armadillos forage for insects in the nighttime and have quirky, fascinating lifestyles.

But come daytime, I see the dangers of the armadillos’ night foraging when my mother or nursery guests, walking through the fields, face the serious threat of twisting or breaking ankles. Those nocturnal fellas become “nuisance wildlife.” I simply have to trap these guys, take them to somebody else’s swampland, and release them. For a while, I used to shoot them, but one day, I did so, and he went under the house. For days, I could see his fresh trail of blood as he followed his nocturnal route, until finally I found him stiff in the road, and I began to cry over the sadness of it all. Exclusion seems like the best option to me. I’ve learned their habits and know that armadillos generally have a range that’s respected by others. So we leave those that burrow out in the pasture alone, and harass any who come around the house or crinum fields. Our dog is actually our best harasser. It’s sort of elitist, I know, and they probably bother the next farm down, but it’s the best we can do.

We also deal with voles because our no-till management style encourages them. Fortunately, they are not into crinum so they’re not a threat to our main crop. And, for whatever reason, they tend to stay away from our vegetables when we interplant them with the crinum. It could just be that they get their share, and I don’t notice, or perhaps there is some associated resistance, where one plant sort of protects the other.

For the most part, though, crinum have few insect pests. Their long lives are a testament to their tenacity. The first crinum I encountered in my life had been planted in its spot fifty years before I found it and had not succumbed to bugs, fungus, or bush hog. My mother kept it growing for the past thirty years, and now it’s eighty years old—that’s a sustainable perennial. Thriving with little care, crinum lilies fit our management style and our philosophy of balance. We build our soil food web with compost tea, with the addition of fungi, with companion plants, and with crop rotation. Our belief is that healthy soil helps create a balance, preventing huge swings in any insect population. Most of these techniques have been discussed in previous chapters. A lot of what we do is experimental, and we can only give anecdotal reports on how things work. We test and trial new ideas, which are often old ideas reexamined. I don’t know if our experimentation has broad implications outside of our fields, but it’s a great opportunity to teach myself as well as visitors, and it sure gives me an understanding of how to use and help other people use the lessons taught by my mentors.

When crinum lilies, like other bulbs, do have problems, they’re usually significant. Although there have only ever been a few viruses reported on crinum in the United States, I don’t like to take any chances. If someone gives me a new crinum, I always isolate it for the first season. This is a step that home gardeners need to start taking, with found or shared plants, as well. In fact, there are several things that other knowledgeable growers and I do in the field to prevent problems that might be good ideas for home gardeners to consider in general perennial care. We scout fields constantly, watching especially for insects that may cause problems—grasshoppers, mainly. In Florida and other consistently warm parts of the country, lubbers and other grasshoppers eat crinum leaves.

After the flowering season, we tend to let things go. The fields will get weedy, and the crinum leaves do get little rusty spots—in bad cases, we take those leaves away to keep the rust in check. Yes, it might look weedy, but to me it looks like a dynamic, well-balanced natural system where there is enough diversity that no one insect can sweep through or become a huge problem. That look is fine on our farm, and it’s fine in our garden, too. For many of my clients’ gardens, in late summer, when most perennials, including crinum, start to look tired, I cut them back to allow for new growth that will look great in the crisp days of fall.

Outside of my home, as a garden designer and manager, I can’t always be a purist. I have a business of making people’s gardens look the way they dream them. Occasionally I do turn to pesticides, but aside from soapy water and fire ant baits, I can’t list one single insecticide that I’ve used in past few years. No organics, no botanicals, and no insecticides. That change has been good for my body, my family, and the plants that we sell. In college, I had a job spraying camellias at resorts. The pesticide we used was an organo-phosphate, the kind of thing Rachel Carson wrote about in Silent Spring. Research shows that even low-level exposure to it can result in impaired memory and other health effects. I may have moved on, but they’re still using it today; now there’s some other young man or woman spraying the same chemical. And newer research shows that their children will likely have lower birth weights—all this for shiny leaves on a camellia bush. The same chemicals are used on lettuce, blueberries, and lots of other foods, which means you probably have this toxin stored in the fat in your body. But for that new generation of young gardeners or farmers, the exposure to these pesticides is heavy; it is an assault on their health and the health of their families. What happens to them will affect you, too.

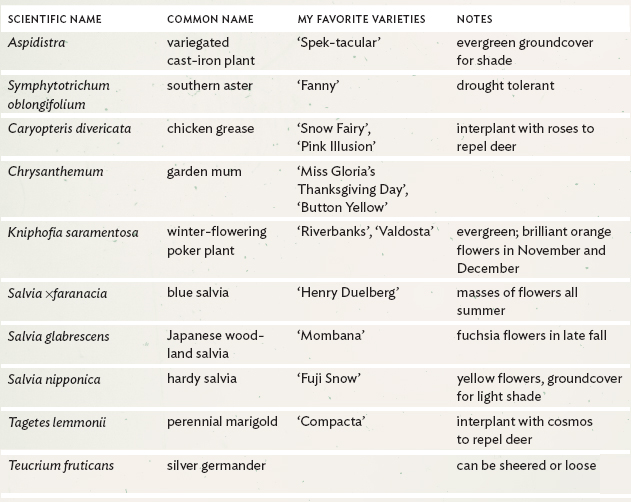

This selection of red hot poker, Kniphofia saramentosa ‘Riverbanks’, was made for its late fall flowers.

In my design work, I sometimes use herbicides and weed killers, but I encourage clients to operate without them, and I design to reduce the use of them. But there are times when they’re unavoidable. One garden that I managed bordered a cow pasture. When I started, it was literally filled with the most tenacious, perennial weeds. We discussed solarization and topsoil removal, but neither was a viable option. So with special herbicides, selected with the advice of a consultant, we spent two months target spraying. We understood the implications and problems we created by depleting the soil of its multiple microbial life forms, so to counteract that, we added a brand of organic, non-manure, woodchip-based compost in a top layer inoculated with soil mycorrhiza, and planted the entire garden with peas to help fix nitrogen and smother the remaining weeds for the remainder of the summer. We planted in the fall.

Still, the garden borders a farm fence, where deer passed every night on one side and a herd of Brangus cows on the other. There are no good options for keeping the deer out, though, so we planted an elegant and unusual mix of heat-loving deer-resistant plants to do the work for us. We even got away with some roses by completely surrounding them with a selection of pungent plants.

Finding the proper combination of plants required serious on-site testing and gardening with the understanding that, even with our planning, this garden might all be browsed on some hungry, icy night. The key is location. No national gardening program promoting plants resistant to any certain pest can be accurate. Plants and wildlife and their responses change with location. One of the commonly touted perennials for deer resistance in garden media is called bluebeard, Caryopteris incana, but that species shrivels in the Lowcountry of South Carolina. It hardly looks good for even one summer. Planting it here for deer resistance is a waste, but you’d be surprised how often it’s recommended. However, C. divericata thrives, and deer won’t eat its leaves, which are so pungent that I’ve always called it chicken grease plant—it smells like the backside of a fast food restaurant. This is just one example of how I look for pest-control solutions in my own gardens. When planning for pest resistance in your garden, seek the experience and wisdom of local botanical gardens and horticulturists. When dealing with any pest it is critical to understand that small changes in climate, soil, and even altitude change everything. A plant that works wonders in one location might have its own issues right down the road.

No matter the hype, most phlox get mildew. Gardenia and crepe myrtle, in humid climates, get sooty mold. If you really have to deal with these or other pests, note the problem, research it, and treat it at the right time. When we see sooty mold in late summer, it’s generally too late in the year to address the problem. As Kari says, you need a professional who has the time and knowledge to understand the lifecycle of pests; and as Miss Hattie recommends, pretend not to care. Plant properly, ruthlessly remove plants that seem to attract pests, and consider that everything is alive and part of the overall system. Trying to control any one part disrupts the other. Let go of the desire to control and be amazed by the desire of plants to thrive.

We have the responsibility of caring for and understanding how our actions affect others. Atrazine, a common herbicide used on lawns and crops that contaminates our drinking water, has been shown to cause demasculinization in male frogs.

To cultivate ethics, you need to understand how your actions and thought patterns make a difference in your own happiness, and the happiness of others. This is a unique potential of the human mind, heart, and brain. It is extremely important to investigate the connection between what you do and how it affects others. If an action would help you, but cause others to suffer, you must not do it.

Science and technology must not violate the laws of nature and the laws of cause and effect, or karma—that inevitably leads to disaster. Natural law is harmonious, creating the physical world, its structure and all the living beings who enjoy the natural world. Altering natural processes creates disharmony and imbalance and the effects are eventually always negative.

Interdependent, peaceful coexistence is the core of the fundamental Buddhist view on who we are, how we survive, what the outside physical world really is, and how it should be taken care of. The earth acts like a mother to all of us. Like children, we are entirely dependent on her. Taking good care of the world and our planet is like looking after our own home for our comfortable living.

Healthy and peaceful survival of all living beings including ourselves is entirely dependent on a healthy and clean environment such as: plants, grasses, flowers, soil, water, and air. Similarly, a clean and healthy environment is entirely dependent on healthy and moral behaviors, actions, and respectful use of the environment.

The use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides on any growing plants or grasses for our convenience is extremely bad for the environment, and ethically wrong. The use of chemical substances directly cause harm to millions of insects and the environment. It indirectly affects us with no escape. The latent force of chemicals and pesticides is much more seriously destructive than their immediate harm. We need a good-looking garden for our pleasures and comfort but surely not through harming other living beings and the environment which is a universal treasure belonging to no individual.

As human beings, each of us has the moral and ethical responsibility to protect the natural world. All living beings have an equal right to live in a healthy environment.