8

Performance, Performativity, and the Constitution of Communities

Consider the following situations, all of which could be analyzed using the concepts of performance and/or performativity, defined in one or more of the various ways we will discuss in this chapter.

1 Two people named Michael (M) and Lori (L) have a mundane conversation about Lori’s work as a musician. The conversation contains a typical number of dysfluencies, repetitions, and false starts. Here is part of their conversation:1

M: Okay but, but I thought you said that you were a musician? How do you get around playing your music when you live in an apartment?

L: Well, well, I’m lucky because, umm, with the equipment I use – I can use headphones to practice so I don’t need to make a lot of noise and, and bother the neighbors.

M: Okay, that’s good because that’s, that’s yeah, that, I would think that would be a problem for somebody playing music.

2 On June 16, 2008, octogenarians Phyllis Lyon and Del Martin were pronounced “spouses for life” by San Francisco mayor Gavin Newsom in the first same-sex wedding to take place in the city after the California Supreme Court legalized same-sex marriage in the state.2

3 A Spanish-language version of “The Star Spangled Banner,” entitled “Nuestro Himno,” was released on April 28, 2006, featuring Latin pop stars such as Ivy Queen, Gloria Trevi, Carlos Ponce, Tito “El Bambino,” Olga Tañón and the group Aventura, as well as Haitian American artist Wyclef Jean and Cuban American hip-hop artist Pitbull. Many Spanish-language radio stations played the new version of the national anthem in advance of the pro-immigration rallies scheduled for the following week. Controversies then emerged over issues relating to language and national identity.3

As different as these three examples are, they represent only a tiny fraction of the types of situations that could be (and have been) analyzed using the concepts of performance and performativity. These concepts have been important topics of study for many linguistic anthropologists because they provide rich and exciting opportunities for understanding more fully how individuals and communities constitute and express themselves linguistically, socioculturally, politically, aesthetically, and morally. Researchers have differed, however, in how they have defined “performance” and the related term “performativity.” Three main approaches can be identified – aligned very roughly with the three examples just presented above:

- Performance defined in opposition to competence. In this Chomskyan view held by most linguists (but by few, if any, linguistic anthropologists), a distinction is posited between “competence,” defined as the abstract and usually unconscious knowledge that each speaker of a language allegedly has, and “performance,” defined as the putting into practice – sometimes imperfectly – of those rules.

- Performativity. This refers to the ability of at least some utterances to do merely by virtue of saying (such as when declaring, “I hereby christen this ship the Queen Elizabeth,” is tantamount to naming the ship). This term originated in the speech act theory of philosophers J.L. Austin and J.R. Searle and was important in shifting the conceptualization of language away from an abstract system of phonology, morphology, and syntax toward an understanding of speech as a form of social action. The concept of performativity has been developed further by the work of scholars such as Judith Butler, who describes gender as a performative process – that is, of continuous acts of “doing” gender rather than a continuous state of being a gender.

- Performance as a display of verbal artistry. Linguistic anthropologists have also defined “performances” as events in which performers display special verbal skills for an audience that evaluates the performers in some way. Examples of such performances include political oratories, storytelling sessions, theater performances, songfests, verbal duels, and recitals of poetry, to name just a few of the culturally variable forms of performance studied by linguistic anthropologists.

Most linguistic anthropologists working in the area of performance have primarily followed one of these three approaches, but some have blended or bridged these approaches in creative ways as well (cf. Duranti 1997:14–17). Before presenting some examples of interesting research on performance and performativity, however, let me explain in greater detail each of the three approaches just mentioned.

Performance Defined in Opposition to Competence

Careful readers will recall that chapter 1 introduced Chomsky’s distinction between competence and performance. Building on de Saussure’s analogous distinction between langue (the language system in the abstract) and parole (actual speech), Chomsky contrasts the competence of a hypothetical “ideal speaker-listener” who knows a “language perfectly and is unaffected by such grammatically irrelevant conditions as memory limitations, distractions, shifts of attention and interest, and errors” (1965:3) with performance, which he defines as “the actual use of language in concrete situations” (1965:4). In later writings, Chomsky alludes to “pragmatic competence,” which “places language in the institutional setting of its use, relating intentions and purposes to the linguistic means at hand” (2005[1980]:225), but the goal of linguists who study pragmatic competence remains the identification of abstract and universal aspects of language use (Kasher 1991). For Chomsky and the linguists who share his approach to the study of language, competence, or what Chomsky has more recently called “I-language” (for internalized language), is the main focus of their research. They consider everyday language use – performance, or “E-language” (externalized language) – to be uninteresting, unsystematic, or unworthy of study. “Indeed,” Cook and Newson write, “Chomsky is extremely dismissive of the E-language approaches: ‘E-language, if it exists at all, is derivative, remote from mechanisms, and of no particular empirical significance, perhaps none at all’ (Chomsky 1991:10)” (Cook and Newson 2007:13).

Linguistic anthropologists have responded to Chomsky’s proposed competence/performance distinction in one of three ways: (1) by redefining what is meant by competence; (2) by reversing the relationship between competence and performance, according performance more centrality and importance than competence; or (3) by rejecting the distinction between competence and performance altogether. Some linguistic anthropologists have combined two or more of these approaches. For example, in a classic article, “On Communicative Competence,” Dell Hymes attempts to redefine and expand Chomsky’s notion of competence in ways that “transcend the present formulation of the dichotomy of competence:performance” (2001[1972]:62). Hymes does not advocate dispensing with Chomsky’s terms altogether, however. It is just as problematic, he argues, for linguists to dismiss performance completely as it is for nonlinguists to valorize only performance. “If some grammarians have confused matters by lumping what does not interest them under ‘performance,’ as a residual category,” Hymes warns, nonlinguists “have not done much to clarify the situation. We have tended to lump what does interest us under ‘performance,’ simply as an honorific designation” (Hymes 1981:81). A better approach, according to Hymes, would be to insist that true communicative competence must include “competency for use” – underlying models and rules, in other words, for actual performance. There are several sectors of communicative competence, according to Hymes, of which the grammatical is only one. “Competence is dependent upon both (tacit) knowledge and (ability for) use” (Hymes 2001[1972]:64; emphasis in the original). Thus, while expanding Chomsky’s original term of competence to include not just grammatical competence but pragmatic or performance-oriented competence, Hymes both undercuts Chomsky’s strictly drawn dichotomy and emphasizes the importance of incorporating sociocultural factors into any linguistic analysis.

Performativity

A second way in which linguistic anthropologists have grappled with what it means to perform linguistically is through the influential concept of “performativity.” The term was first coined by a philosopher of language, J.L. Austin, in a series of lectures he gave in 1955 that were subsequently published in a famous volume entitled, How To Do Things With Words (Austin 1962). Austin’s ideas became the basis for speech act theory and were built upon (some would say in an oversimplified and misguided way) by another philosopher, J.R. Searle (1969, 1975). Since then, speech act theory and, more specifically, the notion of performativity have been taken up by scholars in many different fields of study.

In How To Do Things With Words, Austin sets out to characterize sentences that merely say something – what he called “constatives” (1962:3) – from those that do something – what he calls “performatives” (1962:6–7). While constatives are statements that can be clearly determined to be true or false (such as, “It is raining outside today”), performatives, according to Austin, are those utterances that perform an action in the very saying of them (such as, “I promise to study harder on the next exam,” or, “I hereby dub thee Knight of the Woeful Countenance”). Performatives in Austin’s initial formulation had to begin with “I” and are accompanied by a performative verb, producing phrases such as “I name,” “I pronounce,” “I warn,” “I promise,” “I declare,” “I appoint,” “I order,” “I urge,” “I apologize,” “I congratulate,” “I commend,” “I challenge,” etc. Unlike constatives, which were supposed to have clear truth values, performatives could only be said to be “felicitous” or “infelicitous,” depending on whether the statements were uttered in an appropriate context by individuals with the appropriate authority. Performances also had to be uttered correctly according to convention and with the necessary seriousness or intentionality (1962:14–15). For example, if someone said “I do,” but the wedding ceremony was performed by someone who did not have the appropriate legal authority, “I do” would be an infelicitous performative.

By the second half of How To Do Things With Words, however, Austin has come to the realization that constatives and performatives cannot be neatly distinguished from each other in any consistent way. He therefore decides it is time to make a “fresh start” on the problem and steps back to ask, “When we issue any utterance whatsoever, are we not ‘doing something’?” (Austin 1962:91). At this point, Austin’s ideas about language overlap quite a bit with those of many linguistic anthropologists today who would answer this question with a resounding “Yes!” because they consider all utterances to be forms of social action in one way or another. Austin himself, however, proceeds in a slightly different direction and brackets for the rest of the book his important insight about the performative underpinnings of all language use.

Instead, Austin (1962:108) divides utterances into the following three categories (which he acknowledges overlap and are not always clearly definable):

- Locution. The stating of something. Locutionary acts involve meaning in the traditional sense.

- Illocution. The doing of something instantaneously by virtue of stating it. Illocutionary acts involve conventional force rather than meaning and are performative in nature.

- Perlocution. The consequences of having stated something. Perlocutionary acts refer to effects rather than to meaning or force.

Unlike some of his followers, however, Austin demonstrates considerable awareness of the complexity and overlap among these categories. By the end of How To Do Things With Words he is no longer content to look at sentences in isolation for clues to whether they might constitute action. “Once we realize that what we have to study is not the sentence but the issuing of an utterance in a speech situation, there can hardly be any longer a possibility of not seeing that stating is performing an act” (Austin 1962:138). And he concludes that “in general the locutionary act as much as the illocutionary is an abstraction only: every genuine speech act is both” (1962:146). Nevertheless, Austin still ends How To Do Things With Words by proposing a taxonomy of five different kinds of illocutionary utterances: (1) verdictives (the giving of a verdict); (2) exercitives (the exercising of powers, rights, or influence); (3) commissives (the committing to doing something); (4) behabitives (involving social behavior such as apologizing, commending, or congratulating); and (5) expositives (explanations of how utterances fit into the conversation, such as replying, conceding, or arguing) (Austin 1962:150–151). This taxonomy was later challenged by Searle, who proposed his own five classes of illocutionary acts: representatives, directives, commissives, expressives, and declaratives (Searle 1975:10–13).4 The details of these different categorizations are not worth elaborating upon here; both typologies have been built upon, challenged, or rejected altogether in the decades since they were proposed. Despite the problems that many linguistic anthropologists have identified with the specifics of these categorizations, however, it is important to remember that speech act theory as put forward first by Austin and then by Searle and others advocated a very different way of conceiving of language from that which preceded it. Speech act theorists argued that utterances, rather than merely referring to an already-existing social and material world (Jakobson’s referential function), also act upon and even help to constitute the social and material world. This was an influential development in the study of language and a key move toward a better understanding of how the use of language can constitute social action. Indeed, as Kira Hall notes, “[Austin’s argument that all utterances are performative] is a revolutionary conclusion, for all utterances must then be viewed as actions, an equation which linguistic anthropologists have of course embraced with fervor” (Hall 2001:180).

While recognizing the importance of Austin’s insight that saying is doing (that speech, in other words, is performative), linguistic anthropologists have criticized speech act theorists for some of the principle aspects of their approach. First, most philosophers and linguists who have written about performativity have assumed the universality of their theories. And yet, linguistic practices, language ideologies, cultural notions of personhood, discursive categories and genres, and ideas about agency have all been shown by anthropologists to be highly variable cross-culturally. Linguistic anthropologists have therefore either rejected speech act theory altogether or have suggested revisions to make it more applicable cross-culturally.

Another anthropological criticism of speech act theory concerns the theory’s methodological foundations. Austin and Searle, like most philosophers and many linguists, construct their theories on the basis of intuition or anecdotal personal experience rather than on systematically collected empirical data. A scholar employing such an approach runs the risk of falling prey to unexamined cultural assumptions, language ideologies, and biases – and indeed, this is exactly what anthropologist Michelle Rosaldo argues was the main weakness of Searle’s version of speech act theory. In a widely cited article, Rosaldo (1982:212) claims that Searle “falls victim to folk views” when he assumes that meaning resides primarily within autonomous individuals. Rosaldo argues that the Ilongots of the Philippines, in contrast, have very different ideas about meaning, communication, and language, viewing language as thoroughly embedded within webs of social relations. The Ilongots’ default type of utterance is not a referential sentence (a “constative,” in Austin’s original terminology) that reports on an external state of affairs but is instead a directive or command. Moreover, Rosaldo maintains, because Ilongots are disinclined to attribute intentionality to autonomous individuals and are uninterested in giving or receiving promises, they do not have the same categories of performatives that Searle suggests are universal. In particular, Ilongots do not exhibit expressives or commissives, two speech act categories suggested by Searle that involve expressions of individual feelings or intentions. This is because Ilongots, according to Rosaldo,

[lack]something like our notion of an inner self continuous through time, a self whose actions can be judged in terms of the sincerity, integrity, and commitment involved in his or her bygone pronouncements. Because Ilongots do not see their inmost ‘hearts’ as constant causes, independent of their acts, they have no reasons to ‘commit’ themselves to future deeds, or feel somehow guilt-stricken or in need of an account when subsequent actions prove their earlier expressions false. (1982:218; emphasis in the original)

Searle’s over-emphasis on individual intentions and over-generalizing on the basis of performative verbs within English should be read, Rosaldo claims, not as a convincing case for the universality of speech act theory but rather as Searle’s unwittingly culture-specific ethnographic account of his own ideas regarding language, action, and personhood (1982:228).

Many linguistic anthropologists have also rejected the limited and overly simplistic notion of context used by speech act theorists.5 According to Austin, in order for a performative utterance to work (to be “felicitous,” in Austin’s words), “There must exist an accepted conventional procedure having a certain conventional effect, the procedure to include the uttering of certain words by certain persons in certain circumstances” (Austin 1962:26; emphasis in the original). Despite the centrality of context to speech act theory, many scholars argue that context remains an afterthought to these scholars. R.P. McDermott and Henry Tylbor, for example, claim that speech act theory uses “a soup-in-the-bowl approach to context,” the problem with which is that “it allows the assumption that the soup exists independent of the bowl, that the meaning of the utterance remains, if only for a moment, independent of conditions that organize its production and interpretation, that meaning exists ‘on the inside territory of an utterance’ ” (McDermott and Tylbor 1995:230). Instead, these scholars and many others maintain that utterances and their various contexts are mutually constituted; utterances therefore cannot stand alone.

Yet another famous critique of speech act theory emerged from Jacques Derrida’s pointed exchange with Searle over the basic principles of the theory (Derrida 1988; Searle 1977, 1994).6 Derrida, a philosopher and one of the founders of deconstruction within literary criticism, takes issue especially with the role of individual intentionality in speech act theory; indeed, Derrida claims that intentionality is the “organizing center” of Austin’s work (Derrida 1988:15). Derrida states that meaning is always and everywhere at least to some degree indeterminate and detached from individuals’ intentions. This indeterminacy is crystallized in a term that Derrida coined, différance:7 the “irreducible absence of intention or attendance to the performative utterance” (1988:18–19). Playing with and combining the verbs in French that mean “to defer” and “to differ,” Derrida creates the term différance to refer to the way in which the meaning of a given word (for example) derives from how it differs from other words that it is not. Thus, the meaning of “dog” emerges from its opposition to words like “cat” or “person” – an approach similar to de Saussure’s notion of linguistic value. Also, meanings are never singular or permanent, according to Derrida, but emerge in particular contexts that are linked together through the repetition of a term (its “iterability” or “citationality”) within those contexts over time.

While this overly brief, overly simplified description of Derrida’s deconstructionist literary theory has probably obscured and confused more than it has illuminated, the important and ironic point to note for the purposes of this chapter is that despite Derrida’s scathing criticism of Austin’s notion of performativity, the concept has become extremely popular among Derridean literary critics as well as researchers in many fields. The widespread use of the concept of performativity has led some scholars, such as David Gorman (1999) and John Searle himself (1994) to bemoan the lack of engagement or familiarity with Austin’s actual writings among many literary critics who discuss performativity in their work. Gorman, for example, writes, “In all such work, Austin is repeatedly cited as an inspiration or precedent, but the unasked question is always whether there is any actual basis in Austin’s thought for using such a generalized notion of performativity as a tool of analysis” (1999:98; emphasis in the original).

While this criticism is often warranted, there are nevertheless many scholars who have used the concept of performativity in interesting and illuminating ways, even if they have not always remained faithful to Austin’s original formulation. Let us therefore turn now to a discussion of the work of Judith Butler (1999[1990], 1993, 1997) a scholar who has broadened and redefined the concept of performativity in ways that have been taken up by many linguistic anthropologists as well as by researchers in a variety of other fields.

In applying the concept of performativity to gender, Butler explicitly states that she takes her cue from Derrida (Butler 1999[1990]:xv). But what she borrows from Derrida is not his criticism of Austin but rather his analysis of a short fable by Franz Kafka, “Before the Law” (Derrida 1992).8 In analyzing Kafka’s story, Derrida suggests that the authority of the law is a type of self-fulfilling prophecy; it arises from the acts of those who presuppose the law’s importance and from those who attribute a certain force to it because in so doing, they thereby bring the law into existence (Derrida 1992). Similarly, Butler claims that gender is not essentialist, unchanging, or interior to individuals but rather is continuously produced, presupposed, reproduced, and reconfigured through individuals’ acts and words:

Such acts, gestures, enactments, generally construed, are performative in the sense that the essence or identity that they otherwise purport to express are fabrications manufactured and sustained through corporeal signs and other discursive means. That the gendered body is performative suggests that it has no ontological status apart from the various acts which constitute its reality. (1999[1990]:185; emphasis in the original)

In other words, gender is not something we have in an unchanging, essentialistic way but rather something we do repeatedly and continuously throughout our lives. According to Butler, people actively create and recreate their gendered identity by wearing certain clothes, using certain phrases or tones of voice, or engaging in certain activities such as sports or sewing. In short, Butler takes Austin’s insight that to say is to do and transforms it into a claim that to say or do is to be. Rather than being expressive of a pre-existing, stable identity, then, gender is performative, Butler argues, because people’s social and linguistic practices “effectively constitute the identity they are said to express or reveal” (Butler 1999[1990]:192).

Butler’s formulation of the performative nature of gender has been enormously influential, not just in gender studies but in other fields as well. Many scholars studying ethnicity, racialization, and other facets of identity formation have also used the concept of performativity in this way, either because they have been influenced by Butler’s work or have independently concluded that what they are studying should be understood as an ongoing process of doing rather than a static process of being. In addition to these scholars who are interested in how performativity might help explain processes of individual identity formation, there are others who apply the concept to the processes of social group formation more generally. Bruno Latour, for example, a well-known anthropologist of science and an advocate of the Actor Network Theory (ANT) approach discussed in chapter 7, argues that all social aggregates are performative because “if you stop making and remaking groups, you stop having groups” (Latour 2005:35).

At times, scholars who use the concept of performativity in a way similar to that of Butler combine that perspective (either knowingly or unknowingly) with a very different sense of performance – that of displaying a particular skill for an audience’s evaluation. Performance as display is the third sense of performance/performativity that will be discussed in this chapter and is addressed more fully in the next subsection. “Not everyone writing about ‘performance’ is always careful to separate senses of ‘displayed’ or ‘framed’ performance from that of ‘performativity,’ ” Alaina Lemon writes. But she immediately adds, “Perhaps this is right. Perhaps analytic senses of ‘performance’ should run together where they are conflated in practice” (Lemon 2000:24; emphasis in the original). Butler agrees with this sentiment, asserting that a merger of these two quite different uses of the concept of performance/performativity can be productive because they are related “chiasmically”9 – that is, in a complexly inverted way:

Moreover, my theory sometimes waffles between understanding performativity as linguistic and casting it as theatrical. I have come to think that the two are invariably related, chiasmically so, and that a reconsideration of the speech act as an instance of power invariably draws attention to both its theatrical and linguistic dimensions … [T]he speech act is at once performed (and thus theatrical, presented to an audience, subject to interpretation), and linguistic, inducing a set of effects through its implied relation to linguistic conventions (1999[1990]:xxvi–xxvii).

We will return to Butler’s important but at times frustratingly jargon-laden theories in upcoming chapters on agency and gender. For now, let us explore further the sense of performance involving drama, theatricality, and displays of verbal artistry.

Performance as a Display of Verbal Artistry

A third approach to the study of performance defines the concept as Bauman does in his famous article, “Verbal Art as Performance” – as consisting in “the assumption of responsibility to an audience for a display of communicative competence” (Bauman 2001[1975]:168–169). The presence of an audience is central to this notion of performance. “To pretend that performances of verbal art take place in a social vacuum in which only individual intent matters, that the audience plays no role in shaping such performance, entails a serious failure of method,” argues James Wilce (1998:211). Rather, Wilce reminds us, citing Duranti and Brenneis (1986), audiences should be conceived of as co-performers. Even if the audience consists solely of one person (who could theoretically be the performer herself or himself), the evaluation of the virtuosity of the performer(s) is a crucial element in this approach because performance, according to this view, involves heightened attention to how something is said (or sung, acted, etc.) – or, in other words, to what Jakobson (recalling the overview presented in chapter 1 of his model of the multifunctionality of language) termed the poetic function of language. This practice is highly reflexive:

Performance puts the act of speaking on display – objectifies it, lifts it to a degree from its interactional setting and opens it to scrutiny by an audience. Performance heightens awareness of the act of speaking and licenses the audience to evaluate the skill and effectiveness of the performer’s accomplishment. (Bauman and Briggs 1990:73)

How does one know that such heightened awareness is called for – in other words, that a performance of verbal artistry is underway? Bauman notes that there are culturally specific ways that particular genres of performance are indexed, or “keyed.” Openings such as “Once upon a time …,” for example, alert people who are familiar with the cultural practice of storytelling in many English-speaking communities that a story is about to be told. Similarly, an MC’s announcement (“Ladies and gentlemen, please join me in welcoming …”) serves as a key for other kinds of performances. Even when such formulaic introductory keys are absent, the performance might be made identifiable to the audience members through special seating arrangements or social venues, through special characteristics of the language used, or through special bodily movements or rituals. Some keys that are common cross-culturally include the following (Bauman 2001[1975]:171):

- Special codes, for example, archaic or esoteric language.

- Conventional openings or closings, or explicit statements announcing or asserting performance.

- Poetic or figurative language, such as metaphor.

- Formal stylistic devices, such as rhyme, vowel harmony, or other forms of parallelism.

- Special patterns of tempo, stress, pitch, or voice quality.

- Appeals to tradition.

- Disclaimers of performance.

Each speech community has its own ways of keying performances. Another way of saying this is that each speech community uses keys differently to introduce or invoke performance “frames” (Goffman 1986) – to let people know, in other words, that a performance is taking place. In order to determine which, if any, of these performance keys are used in a given community to trigger a performance frame, a scholar must conduct long-term ethnographic research. Such research is also necessary in order to identify what constitutes performance and what does not among a particular group of people. Is joke-telling a form of performance, for example? How about political oratory, personal narratives, arguments, or recitals of poetry? In every speech community, some speech acts will conventionally involve performance while others may optionally do so or may never do so at all; this can only be determined by studying the culturally specific definitions of, and expectations for, performance. Performances also vary in intensity cross-culturally, and performers may undergo long-term formal training, some informal training, or no training at all. Richard Schechner, a well-known scholar who helped to establish the interdisciplinary field of performance studies, notes that “every genre of performance, even every particular instance of a genre, is concrete, specific, and different from every other – not only in terms of cultural difference but also in terms of local and even individual variation” (2002:162).

What interests linguistic anthropologists the most about performance defined as a display of communicative competence that is evaluated by an audience? As Bauman notes in a recent commentary, for scholars like linguistic anthropologists who focus on how communities are communicatively constituted, “the performance forms of a community tend to be among the most memorable, repeatable, reflexively accessible forms of discourse in its communicative repertoire” (Bauman 2005:149). In other words, because communities are constituted largely through linguistic interactions, studying especially memorable or highlighted forms of communication such as performances will provide insights into how social groups are formed (and re-formed, challenged, reinforced, or disbanded).

In every performance, as in every social interaction, emergence takes place. Emergence, which was discussed initially in chapter 1, is a way of talking about instances in which whole is greater than the sum of the parts.10 “The emergent quality of performance,” Bauman states, “resides in the interplay between communicative resources, individual competence, and the goals of the participants, within the context of particular situations” (2001[1975]:179; cf. Mayr 1982; Williams, R. 1977). The heightened attention audience members pay to performers increases the likelihood that emergent, unpredictable outcomes or meanings will occur. The very structure of the performance itself can even be emergent within the actual performance – reinforced, negotiated, or contested as the performance proceeds. Despite the repetitive, ritualized, or predictable nature of many performances, each individual performance takes place in real time, always with the potential emergence of new understandings. Because of the different roles taken by performers and audience members, and because of their different personal histories, there is absolutely no guarantee that they will interpret the event in the same way (Mannheim and Tedlock 1995:13). And even a single individual may construct different understandings of a performance over time as that individual’s life circumstances change.

It is also important to note that all performances, whether mundane (such as when the telling of a racist joke falls flat) or extraordinary (such as when soaring political oratory mobilizes people to transform their society), are interwoven with social relations of power and therefore have the potential to reshape or reinforce social hierarchies at the micro or macro level. The concentrated attention given to performers – for example, to singers, actors, or politicians in the broader social context, or to jokesters, college professors, or tellers of personal narratives at the more local level – often enables them to have substantial influence on audience members. Performances can be highly transformative events or, conversely, can strengthen existing social hierarchies.

Performances involving verbal art therefore very clearly link language with cultural practices and social relations. In so doing, they contribute to the fashioning and refashioning of individual identities and social communities. For these reasons, linguistic anthropologists have found the analysis of performance to be a particularly fruitful area of study, as the following examples of research conducted by anthropologists on performance will demonstrate.

Ethnographies of Performance and Performativity

A wonderful example of an analysis that draws on several of the theorists and approaches to performance and performativity mentioned in the first sections of this chapter is Graham Jones and Lauren Shweder’s (2003) article, “The Performance of Illusion and Illusionary Performatives: Learning the Language of Theatrical Magic.” Jones and Shweder look closely at how a magician teaches an apprentice to perform a particular magic trick involving a handkerchief. The authors argue that the linguistic practices surrounding magic tricks often go unnoticed or unappreciated even though they are central to creating the illusions that make the magic tricks successful. In the lesson Jones and Shweder videotaped, the magician first performed the trick as he would for an audience, constructing a narrative about a ghost named “Splookie” who first lives inside the handkerchief “house” and then makes the handkerchief rise up and “misbehave” in various ways. Out of respect for the standards of secrecy upheld by magicians themselves, Jones and Shweder do not reveal exactly how the trick is accomplished, but they imply that it involves a gimmick and possibly some mechanism or sleight of hand that makes the handkerchief appear to move on its own.

Jones and Shweder’s main argument is that the narrative the magician tells while performing this trick is essential to the success of the trick. Talk, the authors maintain, can actually shape the audience’s experience of seeing because the narrative of the magician acts, in Bauman’s terms, as a key for the performance, triggering a frame that identifies the event not just as a magic trick but as something involving the paranormal in the form of Splookie the ghost. Throughout the trick, Jones and Shweder argue,

the magician’s verbal routine allows an audience to see a potentially uninteresting sequence of gestures as paranormal – to perceive something otherwise unbelievable. In part, the magician accomplishes this effect through the use of performative speech. In the magician’s spoken routine, the seemingly descriptive narration of an imaginative world of illusion functions through implicit performativity (Austin 1962) to influence the audience’s perception of events. (2003:52)

In addition to this framing of the event as involving a ghost, the magician also creates a coherent plot about the alleged ghost’s behavior. In the process, he attributes agency to the ghost, talking to it underneath the handkerchief and accusing it of trying to escape from him. The magician also enlists the audience’s input and support at various times during his performance, thereby encouraging them to invest in the story, and therefore buy into the act, by participating in the interaction. When instructing the apprentice in the trick, the magician strongly emphasizes the importance of telling a compelling narrative because this will influence how the audience members view the event. “The meaning of the magician’s talk lies not in its descriptive accuracy,” Jones and Shweder assert, “but in the power it has to affect how an audience construes what it sees” (2003:52).

Jones and Shweder directly or indirectly draw on many of the theorists and concepts we have been discussing in this chapter, such as framing and emergence. They also employ Austin’s notion of performativity to describe how the magician’s narrative calls into being a fictive world that then has the potential to influence what the audience members see (or fail to notice). Words, Jones and Shweder (2003:66) argue, have the power to manipulate vision. In addition to performativity, Jones and Shweder also use the concept of performance as put forward by Bauman and Briggs. They note that a magician’s accountability to an audience for the display of virtuosity involves not just physical abilities such as sleight of hand but also verbal skills that construct a narrative and deflect any skeptical comments offered by audience members. In short, Jones and Shweder’s article nicely illustrates how several different theoretical approaches to performance and performativity can be productively combined to shed light on actual events.

Another interesting example of an analysis that draws on some of the concepts introduced in this chapter is José Limón’s (1989) article about the use of aggressive, highly sexualized jokes among Mexican American men in Texas. Here is Limón’s ethnographically rich description of two such interactions:

At two in the afternoon a periodically unemployed working-class man in Mexican-American south Texas puts hot chunks of juicy barbecued meat with his fingers on an equally hot tortilla. The meat or carne has marinated overnight in beer and lemon juice before being grilled. Antoñio, or Toñio, passes the meat-laden tortilla to one of the other eight mostly working-class men surrounding a rusty barbecue grill, but as he does so, the hand holding the food brushes against his own genital area, and he loudly tells the other, “¡Apaña este taco carnal,’ta a toda madre mi carne!” (Grab this taco, brother, my meat is a mother!). With raucous laughter all around, I accept the full, dripping taco, add some hot sauce and reach for an ice-downed beer from an also rusty washtub. (1989:471)

Simón takes Jaime’s hand as if to shake it but instead yanks it down and holds it firmly over his own genital area even as he responds to Jaime’s “¿Como estas?” with a loud “¡Pos, chínga ahora me siento a toda madre, gracias!” (Well, fuck, now I feel just great, thank you!) There is more laughter which only intensifies when “Midnight” in turn actually grabs and begins to squeeze “el Mickey’s” genitals. With his one free hand, for the other is holding a taco, el Mickey tries to pull on Jaime’s arm unsuccessfully. Finally in an effort to slip out of Jaime’s grip, he collapses to the ground cursing and trying to laugh at the same time and loses his taco in the process. (1989:473)

Limón reviews past scholarly analyses of these sorts of “macho” interactions and finds them to be at best unsatisfactory and simplistic, and at worst objectionably stereotypical. In order to understand how these seemingly crude and aggressive verbal (and sometimes physical) interactions can be understood in their full complexity, Limón applies the concepts of framing and emergence. When these men address one another in this aggressive idiom of sexual violation, they frame these interactions as play – as “relajando” or “llevandosale” (1989:477). They only become actual, open aggression when a novice or stranger fails to recognize the signs, or keys, of a playful performance. Because they are an insiders’ way of interacting, these playfully aggressive exchanges offer Mexican American men a way to bond and to build solidarity.

These cultural performances are also multifunctional and have emergent qualities, according to Limón. They allow men who are economically, linguistically, and socially marginalized in the wider society to produce a metaphorical commentary about their own oppression. Their mock aggression indirectly opposes the actual verbal and physical abuse that they experience in these other contexts and therefore has a subversive potential, Limón argues. About the speech play of these Mexican Americans, Limón states, “Created in collective equality, such momentary productions negate the alienating constraints of the historically given social order that exists for mexicanos and affirm the possibilities of a different social order” (1989:479). And yet, the emergent potential of these performances includes not only the possibility that alienating effects of this social order might be temporarily overturned but also the possibility that the men will be reminded of the oppression they experience in the wider world. These playful interactions also index, Limón notes, the men’s own domination within their patriarchal community and the exclusion of women from these contexts (1989:481). Such interpretations and outcomes are just some of the emergent possibilities of these performances.

The challenge of identifying the many possible interpretations and emergent possibilities of any given performance – or, indeed, any social interaction – has been a central issue in some of my own research. In particular, I became intrigued by a specific woman’s festival in Nepal known as Tij. From my first experiences of the yearly festival in the early 1980s when I was a Peace Corps volunteer in the Nepali village of Junigau through my subsequent stints of research there once I became an anthropologist, Tij has always been of interest. The festival is based on Hindu rituals for married women that require them to pray for the long lives of their husbands (and even pray that they die before their husbands). The rituals also require women to atone for having possibly caused men to become ritually polluted by touching them while the women were menstruating or recovering from childbirth. In Junigau, however, the celebration of Tij goes far beyond these rituals, extending weeks in advance and involving feasts for female relatives and many formal and informal songfests at which women sing, men play the drums, and both women and men dance, sometimes even together.

The songfests presented me with the following fascinating paradox: on the one hand, these events are always joyful, with lots of singing, dancing, and laughing; and yet, the lyrics of the songs sung by the women contain heart-wrenchingly melancholy and sometimes defiant lyrics. How can a scholar (or a participant, for that matter) make sense of the seeming contradiction of people lightheartedly singing and dancing to songs with lyrics that could make one cry? Do the participants ignore the lyrics? Or is the lightheartedness merely an act that masks underlying sadness? When the lyrics express opposition to a woman’s arranged marriage, or her excruciatingly difficult daily workload, should these be interpreted as expressions of outright opposition to male oppression on the part of the female singers? Or might these lyrics merely enable the women to let off some steam before returning to their traditional gender roles unchanged?

In an attempt to solve this puzzle, consider some of the lyrics of “A Twisted Rope Binds My Waist,” a song sung at an informal songfest in Junigau in August 1990. The song starts by saying that a young woman has taken a liking to a “flashy” young man and is presumably planning to elope with him. Instead, her parents arrange a marriage for her and marry her off against her will – not an uncommon occurrence in Junigau and elsewhere in the 1990s, even as the number of elopements was increasing (cf. Ahearn 2001a). Here are some lyrics describing the woman’s arranged marriage:11

9 I dug and dug with Father’s hoe

10 And now they fill bridal litters for me in the courtyard

11 As the bridal litters were filled, I was put into bondage

12 Two pennies’ worth of red powder12 caused me to get caught in the middle

* * *

29 I’ll sit on the porch after cutting grass

30 Whose face will I look upon before going inside?

31 If I look upon my lord husband’s face, I feel just like a monkey that’s eaten salt

32 If I look upon my mother-in-law’s face, I feel just like a burning fire

These lyrics do not just contain a woman’s defiant voice, however, but many other voices as well. The lyrics are therefore heteroglossic (a term introduced in chapter 6) in a Bakhtinian sense. The woman’s own voice is evident in lyrics such as the ones just quoted, and at different points in the song she is defiant, resigned to her fate, or conflicted. But there are also other voices, including a narrator’s voice and the father’s first-person voice. Here are the song’s final four lines, the first two in the father’s voice and the final two in the daughter’s:

41 Go without crying, without crying, Daughter; you’ll hear if we call you home

42 It’ll be good to live even in that house

43 If I return home before January/February, you can curse me,

44 But ten times as many curses, Father, go to you13

The presence of all these different voices means that multifunctionality and interpretive indeterminacy are built right into the lyrics themselves – it is impossible, in other words, to come up with a single “correct” interpretation of this song.

Even if there were not such richly contradictory voices within the lyrics of this song, there would still be interpretive indeterminacy, however, for every performance contains emergent qualities that are not predictable a priori from knowledge of the text and/or its performance. In other words, text and context influence each other reflexively, creating a potentially infinite range of possible interpretations upon which participants, audience members, and scholars may draw, both during the performance and over time (Duranti and Goodwin 1992). This does not mean, however, that such indeterminacy, or what Umberto Eco calls “unlimited semiosis,” precludes analysis. Indeed, Eco argues, “the notion of unlimited semiosis does not lead to the conclusion that interpretation has no criteria. To say that interpretation (as the basic feature of semiosis) is potentially unlimited does not mean that it ‘riverruns’ for the mere sake of itself” (1990:6). It is therefore the job of the linguistic anthropologist to identify these interpretive criteria in particular performances (or everyday interactions) by looking for textual, temporal, sociocultural, and spatial constraints on meaning (cf. Becker 2000).

In short, scholars must learn to be more humble and less authoritative in their assertions regarding the “meaning” of any given performance – or, indeed, of any ordinary interaction. Instead of producing a single, definitive interpretation of an event, I suggest a shift in focus from a search for such definitive interpretations to a search for constraints on the interpretive indeterminacy of that event. According to this practice theory of meaning constraint, we can constrain the range of possible interpretations that might emerge from an event such as a songfest, a jokingly aggressive interaction, or a magician’s performance by closely analyzing the words that are uttered while also learning as much as possible about the individual participants, their personal histories and relationships to one another, the general social and cultural norms, and social conflicts, hierarchies, or transformations more broadly. This contextual information, in combination with a close analysis of the words spoken, written, sung, or recited, will enable the researcher to eliminate unlikely interpretations and focus in on the most likely meanings that participants might take away from the event, either immediately or over time as their life circumstances change.

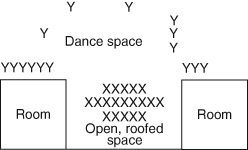

To provide just one example of how these contextual concerns might shape, and be shaped by, the lyrics of “A Twisted Rope Binds My Waist,” let us look briefly at the gendered spatial configuration of the participants during a songfest during which the song was sung in 1990. Women at songfests in Junigau generally all sit closely together, and this was also the case at the Tij songfest analyzed here. Men, on the other hand, place themselves around the outskirts of the courtyard. (See Figure 8.1 for the spatial configuration of the songfest at which “A Twisted Rope Binds My Waist” was performed.) Although the spatial configuration varied quite a bit throughout the songfest, the general pattern remained: women clustered toward the center, men spread out more widely around the edges, encircling the women and the dance space.

Figure 8.1 Spatial configuration at August 1990 Tij songfest in Junigau (X = woman, Y = man).

Source: Reprinted from Ahearn (1998:67).

The men’s encircling of the women could be interpreted as the men’s exclusion from the women’s singing – the central focus of the event. This is indeed a possible reading of the spatial configuration of the songfest that should be considered. But given the broader array of gendered spatial relations in the village, I would maintain that this interpretation should be put aside, or at least qualified in several ways. There are many spaces within the village and beyond that women are either prohibited from entering, at least at certain times of the month, or during certain events, and many other spaces in which their movements are quite circumscribed.14 Physical space is certainly not the only, or even the most important, confining factor in Junigau gender relations, but in many respects it is the most visible. In the case of Tij songfests, potentially oppositional song lyrics are sung by women who are confined (or who confine themselves) spatially by men who encircle them. Periodically, one of the men will reach into the group of women to pull one of them (sometimes quite forcibly) out into the dance space. While this spatial pattern undoubtedly acts below the participants’ level of awareness for the most part, I would contend that it nevertheless exerts a powerful semiotic influence on the meanings that emerge (or do not emerge) from Tij songfests in Junigau. The effect is one of partial physical and linguistic containment of women and women’s words by men.

I hasten to add that this spatial model does not render women passive. Although men are often physically quite rough on the women they try to coerce into dancing, the women themselves sometimes attempt to specify the conditions under which they will allow themselves to be dragged into the dance space. The sequencing of dancers at a Tij songfest thereby becomes a complex choreography that is jointly negotiated by women and men, albeit from unequal social and spatial positions. Thus, Junigau songfests are therefore multifunctional, embodying potentially subversive elements that, given a more conducive environment than the one that has existed over the past several decades in the village, might give rise to oppositional actions that make gender relations more egalitarian.

Such conditions do not, however, seem to be emerging in Junigau, despite numerous transformations in all aspects of life in the village. In fact, during the two days of “official” Tij songfests in 1996, the environment seemed anything but conducive to oppositional readings of Tij lyrics. Young men who had gotten drunk on distilled liquor from outside the village began to fight among themselves, and several times the women had to jump up and move as the groups of fighting men approached. Each time the older men chased the younger men away and urged the women to sit back down and resume singing. Eventually, though, the women, including myself, got tired of rushing to safety whenever the fighting men neared, and the songfests ended much earlier than usual that year. Whether intentionally or unintentionally, the men had displaced the women altogether, truncating their celebration of Tij.15

Thus, while the participants in the August 1990 performance of “A Twisted Rope Binds My Waist” might have constructed many different interpretations of the song, in my search for constraints on this interpretive indeterminacy, there are some interpretations that the participants most likely did not construct, either at the time of the performance itself or in the years since then. After applying a practice theory of meaning constraint, I can state with confidence that it would be too simplistic to interpret the song either as expressing outright resistance or as providing a mere blowing off of steam that serves to rechannel the women unchanged back into their “proper” roles. The multiple voices and shifts in footing within the lyrics themselves argue against such either/or interpretations. Social, cultural, historical, and spatial considerations add contextual richness to the analysis and also strongly suggest that a simplistic interpretation of the song as either resistance to patriarchy or resigned acceptance of it would be misguided.

So what did the song performance “mean” to the participants? I cannot answer this question definitively, but, as I have indicated here, I can rule out some of the least likely interpretations and note some of the possibilities that are emergent within the performance itself. Meanings of performances (or any linguistic interactions) do not reside singularly and statically in the words themselves or in individuals’ heads but rather are co-constructed by communities of language users together. Close analysis of the intertwining of texts and contexts can help scholars identify constraints on the range of possible interpretations that might emerge from a given performance.

In this chapter, we explored various uses and definitions of the concepts of performance and performativity. The three main approaches that have most strongly influenced the work of linguistic anthropologists are: (1) performance defined in opposition to competence, as proposed by Chomsky and later refined by Hymes; (2) performativity, as defined in the speech act theory of Austin and Searle and later transformed by Butler, Latour, and other scholars; and (3) performance as a display of verbal artistry that is subject to evaluation by an audience, as elaborated upon by Bauman, Briggs, and others. Linguistic anthropologists have built upon and sometimes combined these approaches in interesting and important ways, drawing on concepts like framing, keying, and emergence to learn how communities use language to create social actions performatively, and how they use performances to help define or redefine themselves as a community.

In the process of this analysis, we have touched upon the relationship between language and gender, race, ethnicity, power, agency, and social change. These will be the central themes of the final part of the book.