Brad Blanton’s pleasant, friendly face fills my screen, and his Texan drawl – the only word society has yet come up with to describe that accent – booms through my office.

He looks like a man who should constantly be holding a whisky tumbler.

We like each other immediately, but he still thinks I’ve been ‘a goddamn idiot’.

This whole thing could have been avoided, he tells me, if I hadn’t.

Me? I want to say. Has he taken nothing in?

I’ve told him all about Madam Hotdog. I’ve explained precisely what happened. I’ve painted the picture as accurately and honestly as I could. And yet still he thinks all this is somehow my fault.

‘What you did is, you lied,’ he says, accusingly. ‘You lied from the beginning!’

‘I lied?’

‘You lied! You should’ve said, “GET ME MY GODDAMN HOTDOG, BITCH!”’

Has he gone mad?

‘You should have said, “This is a PROBLEM. I’M a problem. I’m going to BE a problem. And you’re going to HAVE a fucking PROBLEM. We have a PROBLEM. Fuck you, bitch!”’

That seems a little strong, I tell him. I’d only just met her.

‘But that would be the first honest response,’ he says, suddenly calm again. ‘So she took your typical British politeness as what it is – which is a goddamn lie.’

‘But politeness is a virtue,’ I say, pathetically, and he waves this away like a king waving away an unpleasant potato.

‘Most politeness is just lying. Often, the truth is rude. And what’s important is that you stick with people beyond the initial rudeness and don’t just do a drive-by. Don’t just be rude and run off. You say, “LISTEN, BITCH: I don’t know what your goddamn problem is, but you better GET MY HOTDOG for my son or I’m gonna go in the goddamn kitchen and get it myself!”’

I’m slightly startled by this. I remind Brad that all this took place in a very middle-class town in Britain.

‘EXACTLY. Everyone in Britain is pissed off about the politeness. Everyone is pissed off in Britain and they’re pissed off from overly polite people. Politeness is a goddamn cover story for goddamn lying.’

There is something incredibly liberating about speaking with Brad.

It’s cathartic, listening to him rail against the hotdog-based injustices I have faced and my subsequent attempts to make sense of them. But I tell him that despite attending a radical honesty workshop in Germany, this level of ‘honesty’ is not in me.

‘You probably haven’t done it before but it would be good for you. Actually, you know what?’

‘What?’

‘I recommend you go back and tell that bitch you resent not getting your goddamn hotdog for 60 fucking minutes and to kiss your goddamn ass!’

I want to! I want to do just that!

‘And tell her, what she said about you being the kind of people who’d wait 45 minutes for fish and chips? Tell her “Fuck you, bitch – stick ’em up your goddamn ass!”’

I’m starting to laugh hard, and so is Brad, because maybe he’s right. I didn’t see it during the workshop, but maybe sometimes the truth can set you free. Maybe I am all those things I thought I wasn’t. Maybe I thought my standards were just high, but what if in fact I am repressed? What if I worry too much? What is the worst thing that could have happened if I’d done exactly what Brad is suggesting and then got on with my day?

I mean, this would have been a pretty short book, but we all make sacrifices.

Wait, though – my son.

What would I be teaching that little guy – all big brown eyes, sponge-soaking this in – if that’s what I’d done? Isn’t being a grown-up about suppressing those urges? Not calling people bad words? Isn’t it about teaching others the right way to act, not selfishly doing whatever you want? Every young parent instinctively tries to make kids understand the correct way to behave by wheeling out ‘How would you like it if someone behaved that way to you?’ – the parental equivalent of ‘Treat others as you would wish to be treated.’ It is in us.

Unexpectedly, this throws Brad.

‘Uh, well, don’t do any of that in front of him,’ he says, his ‘flow’ broken. ‘I mean, if you go in and he’s still outside, then give her all kinds of shit.’

‘That’s interesting,’ I say. ‘So I can be honest … but not in the company of children?’

Does he believe in radical honesty or not?

‘Well, I mean, you don’t wanna scare your son … basically … you have to do something …’

He resets.

‘I think being a good role model of impoliteness would be a good virtue to have, for your son. I think it would be of benefit to him. Don’t be such a lying, polite person.’

Thing is, I don’t want my son to be the type of man who walks into diners and immediately blows up at people and calls them ‘bitch’ and threatens to stick chips in their bottom.

‘I don’t think many kids need lessons in rudeness,’ I say.

‘That’s what I love about them!’ booms Brad. ‘We should be modelling ourselves after them. Not the other way round. Kids tell the truth.’

I tell Brad that my son did, in fact, call the woman rude, though not to her face. But he did go further and told strangers he didn’t even like his hotdog. A sense of injustice at inexplicable rudeness begins at a very young age, and when he hears this, Brad nearly implodes with joy.

‘Good for him!’ he says, laughing and applauding. ‘Do what your son does! He was the role model that day!’

Again, he urges me to go back to the diner one last time and make my feelings known.

‘It’s been about six months,’ I tell him, hoping I can get out of it.

‘Well, that hotdog is cold now,’ he says. ‘But it would be good practice for you. You really want to become knowledgeable about rudeness? The reason that you’ve done all this work is that there is something about rudeness which attracts you. It’s not just repulsion. It’s also attraction.’

He leans forward, now much more serious.

‘If I can connect with someone, and say “I resent you for making me wait while you had your thumb in your ass while I stand there waiting for a goddamn hotdog” … if I can say that and just stay there … and she yells at you, and you yell back, and then you just stare at each other … you can get beyond rudeness. One of you smiles, and you say, “Okay, where’s my hotdog?”, and she says, “Okay, I got it.” You can get beyond rudeness, but you can’t get beyond goddamn lying phony politeness.’

I think about how to do it and pitch it to Brad.

‘So I return to the diner, I order a hotdog, and I say, “I think you were a terrible woman that day, and I would like your response to that”?’

His face falls.

‘Yeah, that’s … okay. But it’s still a little … look, just walk in and say this: “I resent you for the goddamn hour I wasted in your shitty little restaurant.”’

Deep down, I knew Brad was right. I had to confront this head on.

I tell my son we’re going for a hotdog, and he looks delighted.

He runs through a few of his favourite places. Ed’s Diner? Dog Eat Dog on Essex Road? Herman ze German?

‘No,’ I tell him. ‘Do you remember that place last year when we tried to buy a hotdog?’

He scrunches up his nose. Vaguely. It’s almost as if he has not been thinking of nearly nothing else since it happened.

As I fire up the GPS and we start the drive – and my son points out we seem to be going a very long way for a hotdog – I go over the lines Brad gave me.

‘Tell that bitch you resent not getting your goddamn hotdog for 60 fucking minutes and to kiss your goddamn ass!’; ‘I resent you for the goddamn hour I wasted in your shitty little restaurant.’

I think about how they would go down with some of the people I’ve met recently.

A thought comes into sharp focus; something that had occurred to me around the time of my trip to Germany. I’d struggled to articulate it properly to anyone before now but, after speaking with Brad, I worked it out.

What if, actually, we need rudeness because rudeness keeps us in check? Only if we have something to rebel against can we rebel against something.

When I talked with the ethicist Jack Marshall about the crazy world of Donald Trump, he told me about the day, decades ago, he met a man named Herman Kahn.

Kahn was widely regarded at the time as the smartest man alive. He was a futurist who helped develop America’s nuclear strategy, and was the inspiration for the title character of the 1964 film Dr Strangelove.

‘By dumb luck,’ Jack told me, ‘the US Chamber of Commerce had this mini-conference of about 20 people and I was supposed to be at it. By a complete mess-up the only two people who showed up in this big room were Herman and me. So I got to spend two hours with him waiting for everybody else to show. Herman used to charge $25,000 an hour for people to come and talk with him. So he and I just sat there chatting, and he was just sending ideas out into the air.’

One of these ideas really chimed with me.

The two had begun talking about a time of huge cultural change – the 1960s.

Jack said it struck him that the 1960s were a time in which people took established behaviours and just threw them out of the window. Did things differently. What you wanted to do took precedence over what you were ‘supposed’ to do.

‘And Herman said, “Yes – the sixties was a period of mass stupidity where everyone suddenly forgot everything they learned and why they had learned it.”’

The idea was: only once you’ve thrown all the rules out of the window – when you’re running around in the street screaming obscenities while off your face in your underpants – do you realise why those rules were there in the first place.

‘They learned very quickly why it’s a bad idea for people to take drugs. They discovered that, actually, dress codes were a good idea to demonstrate mutual respect. And also why it’s not a good idea to run out into the street yelling “fuck” all of the time.’

Herman laughed, and said, ‘The problem with cultural tradition and civilisation is that after a while they just become tradition and no one actually understands why they have become tradition.’

It is natural for us to want to do things differently and to see rebellion as attractive and refreshing. It’s what appeals to Brad Blanton. It’s certainly also what led to a glut of by-the-number bad guy TV judges; what appealed to those who ticked ‘Trump’. They rail against do-gooders. New men. Caring and sharing. Pompous left-wing sensibilities, all. They find considering the feelings of others annoying, restrictive, weak. It stops them enjoying themselves.

In each generation is a movement of people who want to change the status quo.

But I have come to conclude, and I put it to you, that some ideas are so good – and so useful – that they have to stay in place. They are tradition because they have earned it; they work.

‘People say, “Why do we have to be civil?”’ Jack said. ‘“What difference does it make?” Well, there’s a good reason why all these various traditions of respect for each other – holding doors open for each other – come about. And reasons for the many things that built a culture of kindness and mutual respect. But people take it for granted, and say, “This is what old people do. We don’t have to do it anymore.”’

As we left the city and found the motorway, I thought about how, whether we realise it or not, we’re all suffering.

The week before, I met a London cabbie who told me that that very day a man in a braying, drunken mob outside a pub had shouted ‘Fuck you!’ at him as he drove past and it was so confusing that five minutes later he had absolutely no idea where he was or where he was going. Instinctively, I explained to him why this had happened: his frontal lobes had been fiddled with. He looked at me oddly.

In Los Angeles, I’d spoken with a hotel concierge who told me, very specifically, that in his experience Brazilian women are the rudest. His friend agreed. ‘Brazilian women, yeah.’

But let us not forget that cultures differ; in Brazil the ‘okay’ sign is considered the very height of rudeness. Maybe those guys were overusing it.

The day I’d left Germany, I spoke to a team of Spanish air stewardesses waiting for their airport shuttle bus. ‘Parents’ can be the rudest passengers, apparently. It’s the lack of space, the lack of air, the sheer stress of not being able to shut off in an environment in which shutting off is what everybody else does to survive it.

One day I’d talked with a team of similarly stressed, baggy-eyed removals men. They told me that moving house is commonly thought to be the most stressful time in a person’s life, and they see that every day. Mind you, they told me, it was the wealthier people you had to watch out for. Their version of rudeness is that they simply won’t address you – they’ll just complain about you to your boss behind your back, and that’s worse. (And as we’ve discovered, they’re also far more likely to steal sweets from children.)

And outside a shop near New York’s Columbus Circle, I’d spoken with a homeless guy who told me it’s the ‘people in suits’ who are rudest. They look down at you, pretend you’re not there: ‘You don’t matter.’

Again and again, it seems rudeness is often about not seeing others, not feeling you’ve been seen, and our fundamental human need for respect – something the city often allows us to step around.

Brad didn’t want me to step around anything. He wanted me to stride back into this diner and offload more rudeness in the most forthright way possible. I realised this was just a way of making sure I was seen. Making sure I was listened to, that I had my say, that I fought for my honour. It’s all I’d wanted that first day, after all.

But I was concerned that just offloading more rudeness was the wrong thing to do. I wondered whether there was a higher ground to be taken.

I remembered the limo driver called José I’d met outside my hotel in LA, who told me he encounters rude people almost every few hours. How wearing it gets. How bruising. How disappointing. And how he gets back at them with the only power he has. ‘You just ignore them, give them the silent treatment.’

As you know, the Wallace Report backs this up as one of the world’s number one ways of dealing with the rude.

But I knew absolutely that the silent treatment would not satisfy me one bit when it came to Madam Hotdog. Walking back in there and saying nothing would not make my point at all. And this entire endeavour has been about making a point that I want heard.

Because, why give the silent treatment – when you have a voice?

This book, I have to admit, began for a silly reason. It could have been a silly book. But more than ever I’ve come to see that civility is not just important, it’s not just the right thing to do. I’ve come to see that it is vital.

Rudeness is a form of rebellion that we must rebel against. Not because it weakens us, but because politeness makes us stronger. It gels us.

And this means that all of us – you, me, your uncle’s great aunt – have a moral obligation to Say Something. To not just say we hate rudeness, but to call people out on their terrible behaviour wherever we see it happen: the queue for coffee, the passive aggression in the office, the muttered insult to a pensioner.

It’s what Brad thinks too, I think, though perhaps from a slightly different angle.

‘We can enforce this,’ Jack Marshall urgently told me. ‘People have to understand that it matters and the right is not on the side of people who say, “Go impose your standards of speech on everyone else. Don’t be so super-sensitive, don’t get offended at everything.” The important thing to realise is that civilisation involves being civilised.’

Civility is at the foundations of our society. Remove those foundations and let’s watch it all come tumbling down.

And yet those who understand this are seen by others as weak, or too precious, or old-fashioned, or ‘politically correct’.

What I see in those very same people is not weakness, but an underlying fury. A desperation from my fellow rudeness nerds, who talk softly and politely but with quick and sharp exasperation about the people who just don’t get the obvious: that life would be better if we were better.

And yet still we don’t take rudeness seriously.

Remember what Amir Erez said when I asked him why?

‘They find it amusing,’ he said, ‘until they’re on the operating table.’

If we allow the New Rudeness to overwhelm us, to choke us, the whole world will soon find itself on a metaphorical operating table. And as I let my obsession take hold, and travelled around or hammered the phones, I raised the same point with expert after expert. Why not act when the impact is obviously so great?

‘I agree in terms of impact,’ said Dr Robert Sapolsky of Stanford, who also told me that populations in which people are constantly rude to each other also have low levels of ‘social capital’ – meaning people trust each other less, and have less self-belief. ‘And that’s enormously corrosive, in terms of health.’

That metaphorical operating table might soon be a literal one.

Dr Christine Porath agrees: ‘We’re really putting people in a vulnerable position, when we don’t need to.’

What’s more, she and others say that rudeness is ‘deadlier than we think. I think all stress research points to that.’

Health. Wealth. Self-worth. Friendship. Family. The state of the world in general.

All of it chipped away at and damaged by the draining, wearing, corrosive, boring effects of pointless incivility.

And we’re only at the beginning.

The academic study of rudeness, Trevor Foulk told me, is in its infancy. ‘A lot of people thought it wouldn’t do much, and even now people are very, very surprised by the damage even small incidents can do. I think over time these compelling findings about rudeness will start to change things. I think smoking is a good example of this. It wasn’t that long ago that people smoked at their desks, but slowly the research evidence permeated people’s understanding of how bad it was …’

I’ve learned that we can be bad by accident or design. But I’ve also learned that we can be better. We can be more patient, more understanding, less knee-jerk. We can train ourselves to be more compassionate. We can just be polite.

Rudeness, it seems to me, happens in the gaps between people. That microdistance, that little misalignment of thought or direction. The gap that makes someone a stranger. Within that gap is a very thin layer of civility. Just enough to get by. Like cartilage cushioning the bones. We are each of us isolated, but we don’t have to be. We can choose to be part of civilisation. We can choose to be civil.

As I parked up near the diner, I felt nervous. But more than ever I felt I had right on my side. My head had cleared. I was armed with knowledge. I was even armed with my own national survey which, I have to tell you, I don’t think anybody in there would have seen coming.

And let me share something else with you: the Wallace Report goes far deeper than I’ve let on. Because right at the end of that national survey of 2,000 UK adults, I asked several more questions.

Each and every one of them concerning current and prevailing public attitudes towards the acceptable time limits we place on the order and provision of cooked meats.

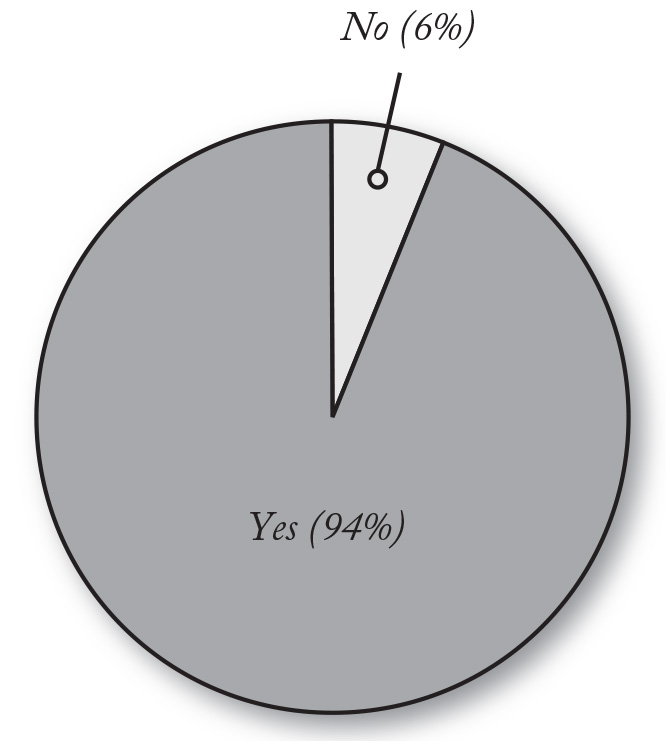

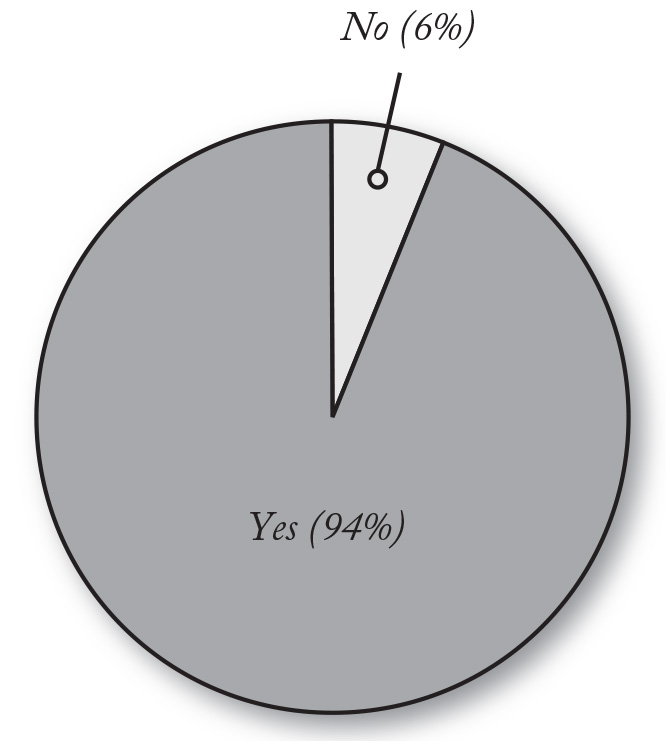

Here is what is now official data.

The longest an average Briton is willing to wait for a hotdog –

even if it is ‘cooked to order’ – is 11 minutes.

Eleven.

Not well over an hour – which I can prove because I have the receipt because she made me pay UP FRONT.

Eleven minutes is the maximum.

Again – even if that hotdog is COOKED TO ORDER.

Even then, that’s from a European perspective. I didn’t tell you this before, but while I was in Los Angeles I hopped on a five-hour flight to New York. In Times Square, I saw a hotdog vendor standing under a sign that read WORLD’S BEST HOTDOGS. I ordered one and timed precisely how long it took to reach me. It took 32.57 seconds from start to finish. I asked the vendor how long it would have taken had it been ‘cooked to order’. He said I could ‘add five minutes’. So that’s the world’s best hotdog in just five minutes thirty-two-and-a-half seconds.

Can you imagine what New Yorkers would say to this man if he took over an hour?

And look at this.

Ninety-four per cent of those surveyed are with me!

Now I was walking down a quiet street and into that diner accompanied not just by a six-year-old boy – but by 61.1 million other people who’ve had enough.fn1 Ninety-four per cent of my countryfolk.

Though the first question is: who the hell are those other 6 per cent and what are they doing with their lives? They are clearly Madam Hotdog’s ideal customers. Or perhaps they didn’t know what hotdogs were and simply thought an hour or more was a reasonable time for someone to warm up a canine for you.

Me? Whatever her day had been like, that woman made me feel like I was a problem customer, just as you’ve been made to feel like one in the past, just as we all have. And yet as it turns out I was merely reflecting the national mood when it comes to the adequate provision of hotdogs. But while 1 per cent would wait an hour then wimp out and say nothing, 93 per cent of Brits say they would then actually complain.

How long we’ll wait for a hotdog, incidentally, varies not just as you move around the world, but as you move around the country. If you’re thinking of launching a hotdog business but you’re worried you might be a little slow: don’t open your flagship store in Wales. Forget an hour. One hundred per cent of people in Aberystwyth will not wait any more than fifteen minutes before they start to bang on the counters and mouth off at you.

Yet arrogant Londoners are the very people who are willing to wait the longest for a hotdog and not complain. Do you

know what that means? I could have been Madam Hotdog’s dream customer all along.

And as I pushed open the door, and I thought of Antanas Mockus and his mimes, and Jack Katz and his sushi flow, and grapefruit cologne and unfair umpires and 101 creative uses for a brick, I braced myself.

This was the moment I would be putting into practice what I’d learned.

This was the moment I would do something.

Because there she was.

My old enemy.

The reason for all of this.

Madam Hotdog.

Just a fleeting glance of her, admittedly, before a gentleman stood in my way, blocking my view.

‘Take a seat,’ he said, and while to some ears he may have said it perfectly pleasantly, for a man we have learned was now inevitably subconsciously primed for rudeness I could not help but detect some weary passive aggression.

So ‘Get out of my way!’ I yelled, pushing him hard in the chest and vaulting over the counter in one heroic move. He grabbed a chip pan and swung it at me wildly, but I was ready and countered it brilliantly, before grabbing a knife block and throwing each individual knife – small, medium, large and extra-large – with such speed and accuracy that he immediately found himself pinned hard against the wall.

‘YOU!’ he said, realising.

Actually, I’m a bit fuzzy on that, I think I may just have taken a seat.

‘What would you like to order?’ said the man.

Well, there was only one option, really, wasn’t there?

‘A hotdog, please,’ I said. ‘And one for my son.’

I kept glancing over his shoulder in case I should see her again. This spectre that had haunted my life all these months.

‘Any drinks?’ he said, and we ordered a Diet Coke and a lemonade, and he nodded and left.

‘This is the place that takes ages,’ said my son, physically deflating.

‘We’ll see,’ I said, in a mysterious voice, but I was beginning to feel nervous.

I wanted to have it out with this place. With Madam Hotdog. To say, ‘It’s me, I’m back, and here’s what I’ve learned.’

I had stats.

I had anecdotes.

I had world-renowned evolutionary psychologists, psychiatrists and barristers on my side.

I thought again about how Brad Blanton had told me to be confrontationally honest. How it complemented the view of Aaron James, author of Assholes: A Theory, when he’d said I’d felt this need to exact respect. I remembered Paul Ford telling me we all feel the injustice of random rudeness, and how natural it is to want to fight for balance.

After 5 minutes and 34 seconds, our drinks arrived.

I tapped my chin with my pen. Five minutes and 34 seconds. As a new expert in both rudeness and hotdogs cooked to order, I considered this acceptable. Although of course in New York, you’d already be one bite into the world’s best.

I kept one eye on the timer on my phone as the wait for my great British hotdogs continued.

Eleven minutes came and went: the time limit most Britons would be happy to wait, even if the hotdogs were cooked to order.

Part of me was thrilled about this.

Fifteen minutes passed.

Wales would have been incandescent.

Twenty.

And then, after 25 minutes and 44 seconds …

‘Here you are!’

I looked down. It was a bloody miracle.

Two hotdogs. Cooked to order. By a man with manners. In less than half an hour!

My son’s – plain.

Mine – with cheese and jalapeño peppers.

There were even chips.

‘Thank you,’ I mumbled, not quite willing to give credit, which was very ungenerous of me.

And still Madam Hotdog remained nowhere to be seen, perhaps plotting in the shadows, sharpening her knives.

My son and I ate our hotdogs in silence. Hotdogs that tasted all the sweeter because they were hotdogs it had taken so long to get.

And they were pretty good. A strong 3 out of 5.

But as we ate them, the weight of responsibility grew heavier on my shoulders. The time was upon us. It was my duty to Say Something.

For me, for Britain, and for the world. To make Wang Tao proud. To make Jack Marshall proud. For every person who’s ever encountered rude service that seemed to come from nowhere and been hamstrung by slow-moving frontal lobes. For every Japanese tourist sent home from Paris confused and sedated and accompanied by nurses, carrying a rudeness contagion they then spread to a whole new set of strangers. To make my case.

But make it politely; non-confrontationally; better than she had.

And, I had decided, to make it in a way that would kill the virus dead: no witnesses, no rudeness hangover, no neurotoxic Butterfly Effect to make the world microscopically worse. Only I, Danny Wallace, could end the strain.

But how?

I caught sight of the ‘TIPS’ jar on the counter – the one that had made me laugh that first day because of its apparent arrogance and pointlessness.

It gave me an idea. I would give them a tip.

I got out a fiver.

And I began to write on it.

25 minutes and 44 seconds is a perfectly reasonable time to wait for a hotdog.

But 94% of 2000 UK adults asked said that one hour and one minute is not.

Even if it is cooked to order.

You’re headed in the right direction.

I paused. And I realised what I had to say next. A sentence that was mine alone to write; a sentence I had earned.

I smiled, and wrote …

I now consider the matter closed.

I initialled and dated it.

I placed my knife and fork back on my plate, stood up, pushed my chair back in, and walked over to the tips jar.

I neatly folded the five-pound note, and quickly dropped it in.

‘Oh, that’s very kind of you,’ said the man, with a warmth I hadn’t been expecting.

‘Not at all,’ I replied, bowing my head very slightly.

‘Thank you,’ he said, and somewhere in the back I heard the sound of heavy approaching footsteps.

‘That was very nice,’ said my son to the man, and as those footsteps got louder, I patted him on the back with pride.