FOUR

National Academy and First Love, 1928–32

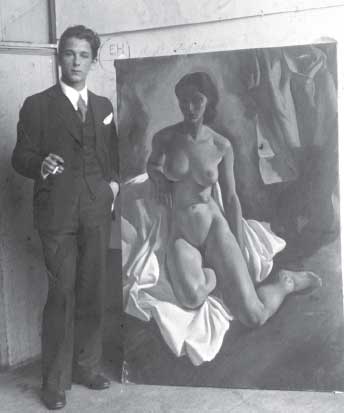

Igor Pantuhoff and his portrait of a nude model, c. 1930. At the National Academy, Igor, a tall, handsome, charming White Russian who boasted of an aristocratic lineage, was easy to notice. Younger than Krasner by three years, he often won prizes for his work.

LATE IN THE SUMMER OF 1928, LEE STARTED AN AMBITIOUS SELF-PORTRAIT to qualify her for the life class at the National Academy of Design. She set herself up outdoors at her parents’ new home in Greenlawn (Huntington Township) on Long Island’s north shore. They had purchased a modest rural house with a separate garage (that might have been an old barn) in May 1926,1 when Joseph was fifty-five and Anna was nearly forty-six. (The 1930 census says that Lee’s parents still lived in the Brooklyn house they rented for $50 a month; Lee and Irving were also still living there.)2 After nearly two decades of physical drudgery and economic uncertainty as fishmongers, Joseph and Anna longed for a country life like the one they’d had in Shpikov. The house, next to a small lake, was simple with no indoor plumbing, but they could grow vegetables, raise chickens, and sell eggs. It was also just up the hill from Centreport Harbor, which offered swimming and fishing.3 They sold some of what they grew.

Getting there was easy via the Long Island Railroad. Krasner had been painting from life even before she left Cooper Union. Now she was working with confidence, producing an oil painting that was thirty by twenty-five inches. “I nailed a mirror to a tree, and spent the summer painting myself with trees showing in the background,” she remembered. “It was difficult—the light in the mirror, the heat and the bugs.”4

Krasner showed herself in a short-sleeved blue shirt and painter’s apron. Her hair is cut short; her rouged cheeks stand out; her eyes are just intense white dots that glint from beneath her trademark heavy eyebrows. One full arm extends across her body to the focal point where her hand grasps a paint-spattered rag and three brushes tinted with color, while the other arm just vanishes at the canvas. By depicting herself in the act of painting, she thus asserts her identity as a painter. Yet the picture contains a puzzle: why does it show her clutching her tools in her right hand while working on the canvas with her left? She was right-handed and painted with her right hand.5 Evidently her mind had not reckoned with the mirror’s reversing effect, exhibiting left-right confusion that today is often considered a symptom of dyslexia.6

Though dyslexia is today known as a common disability caused by a defect in the brain’s ability to process graphic symbols, it was not understood during Krasner’s lifetime. Considered a learning disability, dyslexia does not reflect any lack of intelligence. Dyslexics might start math problems on the wrong side, or want to carry a number the wrong way. Similarly, Krasner habitually began her paintings from right to left, working in a manner that was atypical in a culture that reads from left to right. A dyslexic’s unique brain architecture and “unusual wiring” also make reading, writing, and spelling difficult. Many dyslexics, however, are gifted in areas that the brain’s right hemisphere is said to control, among them artistic skill, vivid imagination, intuition, creative thinking, and curiosity—characteristics that could be used to describe Krasner.

Her lifelong propensity for asking people to read aloud to her as well as her frequent spelling errors and dislike of writing suggest that she suffered from a dyslexic’s confused sense of direction, which often impedes reading and writing. However, as was the case with Krasner, comprehension through listening usually exceeds reading.

On September 17, 1928, nineteen-year-old “Lenore Krasner” formally applied to the National Academy of Design, then located “in an old wooden barn of a building” in Manhattan at 109th Street and Amsterdam Avenue, not far from the Cathedral of St. John the Divine.7 A little more than a week later, she gained admission, with free tuition for the seven-month term. There were about six hundred students there, and for the first time since elementary school, she was with females and males.8

The academy’s creed seemed to mesh with Krasner’s ambition to become an artist: “Only students who intend to follow art as a profession will be admitted.”9 The academy advertised “a balanced system of art education, combining both practical study and theoretical knowledge.”10 Applicants had to practice drawing from casts of famous ancient sculptures until they could qualify for the life class by submitting an acceptable full-length figure or torso drawn from a cast.

Despite her new self-portraits, Krasner had to begin again by drawing from the antique. Even worse, she again faced her old nemesis from Cooper Union, Charles Hinton, who taught the traditional introduction at the academy. Neither the teacher nor the rebellious student wanted to repeat their previous clash. Krasner remembered: “He looked at me and I looked at him, and this time there wasn’t anything he could do about getting rid of me [by sending me to the next level] as it took a full committee at the Academy to promote you.”11

Her opinion of Hinton was shared by her classmate and friend Esphyr (Esther) Slobodkina, who referred to him, with irony, as “our pretty Mr. Hinton” and as a “genteel mummy of a teacher.” She complained that “if not for that dear, kindly Mr. [Arthur] Covey, our teacher in composition, and a few friends that I made, I surely would have gone out of my mind in that completely sterile atmosphere of permanently congealed mediocrity.”12

Slobodkina was an immigrant on a student visa, so she had to sign in at the academy but was so disgusted with the school that she did little more than that. “When Mr. Hinton came to give me his ‘criticism,’” she recalled, “I patiently waited for him to slick up a few spots on my far-from-inspired work while mumbling something about light and shade, and flowing line. The poor, old, doddering cherub knew no more what the real art of drawing was about than the school janitor. Yet he was there for years and years, ruining countless young, fresh, promising talents.”13

Slobodkina was from Siberia, where her father managed a Rothschild-owned oil enterprise. Before arriving at the academy, she had trained in art and become familiar with modernism in Russia. Though she later won an Honorable Mention for Composition in 1932, Slobodkina quickly became disillusioned with the school’s conservatism, as would some of the other more adventuresome students including Krasner, Herbert Ferber, Giorgio Cavallon, Byron Browne, and Ilya Bolotowsky—all destined to make names for themselves.

When Krasner was finally able to present her self-portrait to the appointed committee, they judged it so fine that they didn’t believe it was done outdoors. “When you paint a picture inside, don’t pretend it’s done outside,” they admonished her.14 The committee chair, Raymond Perry Rodgers Neilson, a well-known portrait artist, then forty-two, scolded, “That’s a dirty trick you played.”15

Nevertheless Krasner preferred him over Hinton. “It was no use my protesting, but he passed me anyway—on probation! At this time I had not seen any French painting; I had simply tried to paint what I saw. His reaction was very shocking to me. But now I suppose I must have seemed to him like some smart-aleck kid trying to imitate the French and show them all up. And I assume now they were all worried by the French.”16 In interviews years later, Krasner made much of being admitted on probation. But the catalogue stated: “All new students are admitted on probation” with advancement only by producing appropriate work.

Academy records document that Krasner was promoted to “Life in Full” for a one-month “trial” as of January 26, 1929.17 “Life in Full” referred to leaving plaster casts behind to draw full-time from a live model. A related Self-Portrait survives in pencil and sepia watercolor on paper. To create the work, she glanced back over her shoulder into a mirror; her short haircut suggests that she created this work around the time of her outdoor oil self-portrait. Krasner explained that she had done a series of self-portraits, “not because I was fascinated with my image but because I was the one subject that would stand still at my convenience.”18 After her promotion, her record card for that first year reveals that someone drew a line through Hinton’s name, as she dropped out of his dreaded class. Instead the name “Neilson,” who taught the desired “Life Drawing and Painting” on Tuesday and Friday mornings, was written in.19

Krasner’s outspokenness would keep getting her into trouble. A note on her record card states, “This student is always a bother—locker key paid—but no record of it on record—insists upon having own way despite School Rules.” Krasner was very much a product of her Jewish immigrant culture. Growing up in a large impoverished family and having to fend for herself had made her into a fierce defender of her rights—as she saw them. Furthermore, it had been necessary for her to look out for herself in the poverty-stricken immigrant communities in Brooklyn, where anti-Semitic gangs sometimes caused havoc—a precarious situation all too similar to the one her family had faced as Jews in Russia.

Of the 580 students (238 women, 342 men) who attended the academy that year, only 479 survived the entire school year. Krasner made friends with both men and women, but later mentioned only the men that she’d made friends with, most of whom later won recognition as artists: Byron Browne, Ilya Bolotowsky, Giorgio Cavallon, Boris Gorelick, Igor Pantuhoff, and Pan Theodor.20 One classmate opined that two of the best-looking men were Browne, who was “tall, blond, strong and as radiantly handsome as a summer morning in a northern country,” and Igor Pantuhoff.21

Although most students at the academy were Americans, there were also many international students, including some from Austria, China, France, Hungary, Canada, England, Italy, and Russia. Besides Esphyr Slobodkina, who was only there on a student visa because recently imposed quotas impeded her from immigrating legally, the “Russian” contingent included Eda Mirsky, her sister Kitty, Gorelick, Bolotowsky, and Pantuhoff.

Krasner became especially close to the Mirskys, Eda and her older sister Kitty. The sisters worked in contrasting styles: Eda painted flowers and children in “lavish colors, sensuous shapes,” while Kitty preferred dark and brooding seascapes and kittens. Eda won the School Prizes of $15 for both the Still Life class and the Women’s Night Class—Figure in 1932.

Their Russian-Jewish family had emigrated from Ukraine to England, where the girls were born, then to the United States, settling in the Bronx when the girls were still children. They eventually moved to Edgemere, Long Island. Their father, Samuel, was a self-taught portrait painter who earned a good living, working on commissions from his studio at Union Square. Kitty started studying at the academy two years before Krasner. By the time Krasner encountered the Mirskys, they were living in Manhattan.

The Mirskys were conversant with their father’s work as an artist, and this gave them a sophistication about art that Krasner lacked because she had no such role model at home. Yet the Mirsky daughters also had to deal with their father’s judgment—both his criticism of their work and his high standards for what it took to be an artist. Nevertheless this did not deter them from pursuing art. Eda told her daughter, the author Erica Jong, that she “could have gone to college anywhere I chose—but since Kitty quit school and went to the National Academy of Design, and since she was always coming home with stories of how splendid it was, how many handsome boys there were, how much fun it was, I decided I wanted to leave school too…. Papa let me.”22

Eda became a star at the academy, but with a bitter twist: “the teachers always twitted the boys: ‘Better watch out for that Mirsky girl—she’ll win the Prix de Rome,’ which was the big traveling scholarship. But they never gave it to girls and I knew that. In fact, when I won two bronze medals, I was furious because I knew they were just tokens—not real money prizes. And that was because I was a girl. Why did they say ‘Better watch out for that Mirsky girl!’ if not to torment me?”23 Eda was so frustrated by the sexism that years later she discouraged her daughter, Erica, from pursuing a career in the visual arts when Erica went to the High School of Music and Art and the Art Students League.24

Eda’s granddaughter, the author Molly Jong-Fast, recalled her grandmother “screaming about socialism,” a concern that would have interested her friend Lenore.25 Lenore and Eda’s friendship was so close that Lenore agreed to pose for at least two portraits. They capture Lenore’s likeness and personality with extraordinary confidence. One shows her long, luxuriant hair, while in the later one, clad in a fashionable striped jacket, she sports the short haircut of a flapper. Lenore also gave Eda a self-portrait painted in the basement of her family’s house in Brooklyn.

The basement portrait, a moody, wide-eyed image, resembles the style of Krasner’s future teacher Leon Kroll, who would have appreciated Lenore’s decision to pose before a mirror in half-shadow with the sunlight pouring through the basement window behind her, illuminating a potted plant and one side of her face. The portrait already shows remarkable sophistication and skill. Krasner’s ability was not lost on Eda, who treasured the gift and finally, in 1988, gave it, along with her own two portraits of Krasner, to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Like Krasner, the Mirsky sisters studied with the despised Hinton and with Charles Courtney Curran. Curran, who was nearly seventy years old at the time, was equally old-fashioned in his style of teaching. Born in Kentucky, he had studied at the Académie Julian in Paris and exhibited at the Salon. Curran had won a number of prizes in the 1880s and 1890s in both Europe and the United States. At the time he taught Krasner he also held the prestigious position of the academy’s corresponding secretary. His impressionistic style might have seemed like a breath of fresh air to Krasner had she not been attracted instead to the new Museum of Modern Art and its more radical program of showing Matisse, Picasso, and abstract art.

Krasner was attracted not only to modernism but also to a coterie of Russians who shared her enthusiasm. It was as if she felt at ease with people who shared the origin of her parents, older siblings, and mother’s brother. On her registration card for the academy, the category “where born” correctly reads “New York City,” but to the right on the same line is typed “Russia.” The note reappears on cards for successive years, making it less likely that it’s accidental. Some years, the word Russia follows the letters M and F, which seem to stand for the birthplace of “Mother” and “Father.” Krasner may have been born in America, but she still spent her time with the Russians, most of whom were Jewish. But one of them who caught Krasner’s eye definitely was not.26

A tall, handsome, charming White Russian, Igor Pantuhoff was easy to notice. He was younger than Krasner by three years but boasted of an aristocratic lineage. Gossip about his background circulated among his fellow students and later among his contemporaries. Joop Sanders, a younger Dutch painter who settled in New York, recalled meeting Pantuhoff in the late 1940s through their mutual friend, the artist Willem de Kooning, and said that “Igor was very elegant and good looking with a smooth European manner.”27 Robert Jonas, another artist who befriended both de Kooning and Pantuhoff, later recalled that Pantuhoff’s father was “a captain of the guard of the Kremlin.”28

Oleg Ivanovich Pantuhoff was born in Kiev in 1882—the youngest son of a physician who had been a general in the Army Medical Corps—and had been an energetic young colonel, a commanding officer of the Russian Imperial Guard, and a staff member to Tsar Nicholas II. The tsar commissioned him to start a branch of the Boy Scouts in Russia (the National Organization of Russian Scouts, founded in St. Petersburg in 1909).29 Colonel Pantuhoff became the first Chief Scout and the tsar’s son, Alexei, was the first Russian Scout, placing Pantuhoff quite close to the imperial family.

When Colonel Pantuhoff named his second son Igor, he was expressing his ardent Russian nationalism, because the name recalls a twelfth-century Russian prince whose exploits were immortalized in an anonymous epic, Song of Igor’s Campaign.30 At the time of Igor’s birth, the Pantuhoffs employed a children’s nurse, a maid, a cook, and an orderly. Igor’s mother, Nina Michailovna Dobrovolskaya, was ill for nearly a year after the boy’s birth. At her doctor’s suggestion, she left her family and resided in Davos, Switzerland, and then in a spa near Salzburg. She continued to suffer from asthma and was frequently absent while she visited various clinics in search of a cure.

As small children, Igor and his older brother, Oleg, Jr., lived with their parents in Tsarskoe Selo, the town devoted to the Imperial Palace and also where the last tsar officially resided.31 During spring and winter seasons, however, the two boys went to live with their grandmother in St. Petersburg, just sixteen miles away. They also stayed with their grandmother when their father went off to war.

The Russian Civil War began in 1918. Colonel Pantuhoff served with the White armies against the Bolshevik Red Army and “took part in the last defense of the Kremlin against the Bolsheviks.”32 As the fighting escalated, the Pantuhoffs fled first to Moscow and then to the Crimea on the Black Sea. Food became scarce. In his memoirs, Colonel Pantuhoff described how his family suffered from malnutrition. Both Igor and his brother developed jaundice; Oleg, Jr., became so weak that he could not walk. Their mother was also quite ill and weak, suffering from bouts of pneumonia.

Despite his family’s suffering, Colonel Pantuhoff continued to work with the Boy Scouts, many of whom he later described as “sons or grandsons of men wounded or killed in the world war or the civil war…. Their recent experiences so confirmed them in loyalty to their country and to their church that, even after the Bolsheviks had outlawed scout activity, some persisted secretly in scout work.”33 He also wrote about “a large Jewish Boy Scout group in Sevastopol known as the Maccabees. Their leaders were good men and their boys looked very smart. On one occasion they invited me and other scoutmasters to inspect their unit and then asked to become part of the Russian Boy Scout organization.” After conferring with his colleagues, Pantuhoff “decided that since they were not of our religion and carried a flag with the Star of David, our bylaws precluded their joining us.”34 Pantuhoff would later try to impose this same kind of exclusionary thinking on his sons in America.

During the height of the war, the brothers suffered from either changing schools or having no school at all. Colonel Pantuhoff wrote that Igor, who studied less well than Oleg, “lagged sadly behind in reading” but developed “unquestioned talents in drawing” and “definite talent as an actor.”35 Igor’s parents did what they could with homeschooling. After the Red Army recaptured Kiev on December 17, 1919, the major fighting ended, and the defeated Cossacks fled back toward the Black Sea. Colonel Pantuhoff finally decided to put his safety and that of his family first and joined more than a million Russian refugees from the Bolsheviks. The Pantuhoffs now had to cope with sudden poverty.

They sailed on a freighter from Sevastopol and landed on March 5, 1920, in Constantinople (now Istanbul), which was still under Allied control after World War I.36 The boys were placed in two different boarding schools: Igor’s, Yeni Kioi, had an English headmaster.

The Bolsheviks soon banned the scouts and, beginning in 1922, purged the scout leaders, who either perished or had already gone into exile along with other White Russians. Igor became a Cub Scout in Constantinople until early September of that year, when the Pantuhoffs sailed for the United States, arriving on the tenth of October.

Having moved about during most of Igor’s childhood, the family finally settled down at 385 Central Park West—far in both distance and culture from the Brooklyn immigrant neighborhood of the Krasners. The Pantuhoffs’ lifestyle, however, was not elegant. Like many other immigrants, the family could afford their apartment only by taking in four boarders.37 Igor’s brother modeled his life on their father’s military career, joining the U.S. Army and distinguishing himself as a translator. Igor’s mother had studied art in St. Petersburg at the art school of Ian F. Tzionglinsky, an ardent follower of Impressionism, and at the school of Technical Design of Baron Aleksander Stiglitze. Igor’s father also enjoyed painting, so Igor took after both parents.38

Pantuhoff had already spent a full year at the academy when Krasner arrived there. In October 1928, Pantuhoff won an honorable mention in the required submission category, “A Corner of New York: Noon Hour,” a theme that all competing had to produce. The next spring, Krasner’s second term, he won multiple prizes in the categories of painting from the nude, figure, still life, and composition.39 Since he registered his name as “Igor Pantuckoff,” it appears that he had not yet decided on how to anglicize it. Evidently names shifted among the emigrés; Ilya Bolotowsky was also “Elias” and Giorgio Cavallon also “George.”40 It would take still more time for “Lenore Krassner” to become Lee Krasner.

The new student at the academy caught the attention of the rising star. Just twenty-one, Krasner was outgoing and slender with a model’s figure. She delighted in her first experience in a coed institution since elementary school. She was ambitious and determined to be an artist. To her, Pantuhoff embodied the sophistication of European culture. He exuded style, which was completely missing in her background.

The two soon became a couple. He began to style and present her to the world like a Pygmalion. She enjoyed the glamorous clothing and exotic jewelry he picked for her to purchase, even if her modest budget suffered. Whatever qualms Krasner might have had about Pantuhoff’s attempts to transform her appearance faded in the context of Jazz Age New York, when the image of the flapper redefined modern womanhood. Rigid Victorian customs gave way, leaving young women to cope with sexual liberation. They now had new opportunities to dress in more revealing clothes and to wear makeup, once associated with prostitutes, but now fashionable in the Roaring Twenties.

Pantuhoff’s attention to Krasner earned her some envy. Slobodkina grumbled, “Half the girls in school, including Kitty and Eda Mirsky, hung around him. His particular lady of the time was the extremely ugly, elegantly stylized Lee Krasner. She had a huge nose, pendulous lips, bleached hair in a long, slick bob, and a dazzlingly beautiful, luminously white body.”41 Slobodkina seems to have gotten a surprise from Igor when she first began to attend the academy morning sessions. She wrote in her memoir: “A dashing young man, the darling of the female student body, by the name of Igor Pentukhov [sic] heard of the arrival of a new student, a young lady not so bad to look at and a Russian at that. One late morning he rushed to our all female class, and finding me busily bent over the eternal drawing from the cast of Venus de Milo, unhesitatingly planted a gentle kiss in the temptingly low-cut décolleté of my back.”42 Slobodkina turned around and slapped his face. He protested that he just wanted to meet her and speak a little Russian. She snapped back that she was there to speak English and to learn to paint. “I must say he was not heartbroken.”

Krasner was apparently less rejecting of Pantuhoff’s flirtatious nature. Slobodkina’s memoir documents that it was not unusual among the academy’s students for them to form live-in relationships before marriage. In one case, however, Slobodkina commented that their classmate Gertrude “Peter” Greene was “indefatigable in her search for new partners. I suspect that she had a touch of nymphomania in her” but she and others viewed Krasner as loving and faithful to Pantuhoff.43 In fact many of their teachers and friends eventually believed the two were married.

In contrast with nineteenth-century precepts of womanly virtue, this era began to view sexual activity before marriage as no longer a grave moral breach. It was even commended by some books of advice. “The girl who makes use of the new opportunities for sex freedom is likely to find her experiences have been wholesome…she may be better prepared for marriage by her playful activities than if she had clung to a passive role of waiting for marriage before giving any expression to her sex impulses.”44

Enchanted by Igor, Lee was relieved when her younger sister, Ruth, then only eighteen, stepped up to meet the family’s responsibility of providing a wife for their sister’s widower by marrying him on February 5, 1929. Ruth’s new husband, Willie Stein, operated the projector at the Pearl Movie House in Brooklyn, then owned by his father, Morris Stein.45 Ruth accepted the burden (or the opportunity) of raising Stein’s two small daughters as her own. According to the 1930 federal census, Krasner apparently still lived at home at 594 Jerome Street with her parents, along with her brother Irving.46 Her sister Ruth and her husband, William Stein, along with Muriel and Bernice, his two daughters, also lived at the same address. Lee occupied the basement room and shared the kitchen and bathroom upstairs.

Pantuhoff often visited Krasner at her home. One of her nieces, Muriel, treasured her times with the couple. “I used to sit on [Igor’s] lap and he would tell me stories and give me sips of wine.”47 Muriel remembers that Pantuhoff always had a glass of wine and that he smoked a lot. She also described her Aunt Lee as a frequent and beloved babysitter, who was much needed after Ruth’s only child, Ronald Jay (Ronnie) Stein, was born in September 1930. For Muriel, Lee was “like a second mother”—very kind, helping her with her clothes, taking her out to eat, and teaching her “what the world was like.”48 Lee sometimes took Igor to visit her parents in Greenlawn, especially during the summers, where he would paint Muriel’s portrait and landscapes. Krasner often took Muriel and Bernice to the circus and to shop for clothes, and “other such treats.”49 The sisters found Aunt Lee to be much warmer than their stepmother, Ruth. Aunt Lee often accompanied the girls to the movies at the Pearl, where their father worked until 1929. The theater, which was just north of East New York, had inspired Muriel’s middle name.

The theater opened in 1914 and could draw about five hundred spectators for its second-and third-run films. Muriel recalls how thrilled she was to see Greta Garbo and Clark Gable and be with her Aunt Lee.50 Muriel and her sister viewed their aunt as “a second mother,” who was “kind and generous; she really wanted children and never had them.” Conversely, Lee probably viewed her nieces as if they were her children—at least children whose lives she could enrich without taking primary responsibility for them. Later she would famously dote on their half brother, Ronnie Stein.

When the stock market crashed in October 1929, the academy’s adventuresome students didn’t even seem to notice. No records have survived of any reaction from the students. Indeed it was not until 1930 that the grip of long-term economic depression took hold. Furthermore, for many of the students, especially those from immigrant families like Krasner, there had always been a worry over money.51 Krasner’s acquaintance and contemporary Lionel Abel, a playwright and critic, wrote that in November, “I did not even know that there had been a crash on Wall Street during the previous month. When I say I did not know about the crash, I do not mean that I had not read of it. I mean merely that it had no special significance to me.”52

At the same time that Krasner gained admission to the Life Class at the beginning of 1929, she also enrolled in Charles Courtney Curran’s day class and the night class of Ivan Gregorewitch Olinsky, an affable Russian Jewish immigrant who was a highly successful portraitist who had work in major galleries. Olinsky was born in Elizabethgrad (Kirovohrad in the Ukraine) and emigrated with his family when he was twelve. Just after Alexander III ascended the throne, in April 1881, their town underwent two days of government-sanctioned pogroms. Many Jews were raped or murdered, and their property was destroyed. Olinsky and his family survived and managed to emigrate before an uprising in 1905 when many more Jews met their death. Given Olinsky’s painful experience with anti-Semitism, it is not surprising that he often emphasized his Russian origins over his Jewish identity.53

Luckily for Olinsky, his family settled in New York, where he enrolled at the academy under the artists J. Alden Weir, George W. Maynard, and Robert Vonnoh. He also did a stint working for John La Farge, helping to make both murals and stained glass. Olinsky’s portraits and figure paintings, while academic in style, do show the influence of impressionism. He was purportedly so successful as a portraitist that he sometimes had no work for sale in his studio. He was represented by major New York art dealers such as the Macbeth and Grand Central galleries. Middle-aged, established, and set in his ways, Olinsky nonetheless provided Krasner with a link to her family’s ethnicity. His “Russian” profile at the academy may have represented a new possibility of assimilation and social acceptance for Krasner, whose own family was much more identified with Jewish insularity and isolation. Still, Olinsky offered no new aesthetic direction she could call her own.

That autumn Krasner added a fourth class that would occasion a significant turn in her artistic development—Still Life, taught with criticisms on Wednesday afternoons by the septuagenarian William S. Robinson. Robinson had studied at the Académie Julian in Paris, and the “extra” class that he taught was open to students “sufficiently advanced, whenever they desire to paint from the still life model.” Attendance was required for three afternoons during the week.

Meanwhile Cézanne, Gauguin, Van Gogh, and Seurat were featured in the Museum of Modern Art’s inaugural show on Friday, November 8, 1929. Throngs attended the opening, and the museum announced that it was open free to the public for the day.54 The show’s ninety-eight pictures were revelatory to many, who had to seek them out in the museum’s first quarters, a few rented rooms on the twelfth floor of the Heckscher Building at 730 Fifth Avenue. The museum’s director, Alfred H. Barr, Jr., told the press that “several art connoisseurs who had been known for their antipathy to modern painting were ‘converted’ after seeing the exhibition.”55

Founded by three progressive and socially prominent women—Miss Lillie P. Bliss, Mrs. Cornelius J. (Mary Quinn) Sullivan, and Mrs. John D. (Abby Aldrich) Rockefeller, Jr.—the Modern challenged the conservative outlook of the National Academy. Curious and rebellious young artists like Krasner would naturally be attracted to the promise of a new aesthetic freedom.

Krasner went to the newly opened museum that Saturday with a group of classmates. “We disbanded after leaving the show, and there was no time to compare notes. But on Monday morning we met again at the academy. Nothing was said, but the after-affects were automatic. We ripped down the red and green velvet curtains—they were always behind everything from the wall into the middle of the room. The model came in, he was a Negro, and wearing a brightly checked lumberjacket. He started to take it off, but we all shouted ‘No! Keep your jacket on!’”56 She often spoke of how encountering “live Matisses and Picassos” had an immediate effect on her and had inspired the students, who “decided to do what we saw in front of us.”57

She delighted in telling how, when their portrait instructor, Sydney Edward Dickinson, showed up to give the next criticism, “he was so irritated with what he saw that…he picked up somebody’s brushes and hurled them across the room, saying, ‘I can’t teach you people anything’ and left.”58 Dickinson’s angry response to the students’ visual provocation was particularly startling. Krasner had described him as “a very charming, delightful man, who practically never raised his voice. He was extremely patient.”59

Having studied portrait and still life painting with the conservative William Merritt Chase and figure drawing with the traditionalist George Bridgman, Dickinson was a successful painter of society portraits, but he could not accept modernism.60

Krasner’s work in her still life class suggests that she treasured MoMA’s catalogue long after the show came down. She painted floral and fruit subjects including Still Life with Apples and Easter Lillies, both using a darker palette, though in the latter she daubed orange on the green cloth beneath the vase. However, both Krasner’s modeling of her Apples and her decision to tilt the tabletop toward the picture plane suggest that she had been looking with care at both Cézanne and Gauguin. Krasner signed Easter Lillies as “L. Krassner” boldly on the bottom right.

At the Modern’s inaugural show, Krasner would have seen at least six still life images of Cézanne’s apples. Two of them probably had an impact on her. In Krasner’s Apples still life, she depicts apples piled on a plate seen from above. Her decision to place a single apple to the left, apart from the others on a cloth that does not lie flat, appears to echo a Cézanne then owned by Joseph Winterbotham and on loan for the show. Another Cézanne, from the Étienne Bignou Collection, has a similar arrangement of apples piled on a plate also repeating the visual emphasis on the table’s back edge across the canvas. Krasner’s decision to tip both the table and the plate forward, however, is actually closer to Gauguin’s still life in his Portrait of Meyer de Haan, which was both in the show and reproduced in the catalogue.

“It was an upheaval for me,” Krasner exclaimed, speaking of modern painting, “something like reading Nietzsche and Schopenhauer. A freeing…an opening of a door. I can’t say what it was, exactly, that I recognized, any more than some years earlier I could have said why it was I wanted to have anything to do with art. But one thing, beyond the aesthetic impact: seeing those French paintings stirred my anger against any form of provincialism. When I hailed those masters I didn’t care if they were French or what they were.”61

Krasner also had problems with the academy beyond aesthetic differences. Even the rules that governed painting in still life made her angry. For example, she learned that anyone wanting to paint still life with fish had to do it in the basement, where it was cooler and the fish were slower to rot. The problem was that no women were allowed downstairs. “That was the first time I had experienced real separation as an artist, and it infuriated me. You’re not being allowed to paint a…fish because you’re a woman. It reminded me of being in the synagogue and being told to go up not downstairs. That kind of thing still riles me, and it still comes up.”62

In protest, Krasner, the fishmonger’s daughter, made the forbidden foray into the basement to paint fish with her pal Eda Mirsky, a star student. The faculty was so offended by the girls’ rebellious gesture that it suspended them on December 7, 1929, for “painting figures without permission.” It took the signature of “CCC”—their teacher Charles Courtney Curran—to restore their student status after the suspension. In an interview with Eda Mirsky when she was ninety-nine years old, the artist beamed at the thought of her youthful act of defiance with Krasner. She insisted that it was the only time she got in trouble.63 Surprisingly, Krasner later interpreted the experience differently, saying, “I had absolutely no consciousness of being discriminated against until abstract expressionism came into blossom.”64 This was one of her rare inconsistent moments, which may have sprung from her thinking in a different context.

If Krasner’s rebellious attitude kept her from winning any prizes at the academy, it did not prevent Eda Mirsky’s recognition there—at least the small prizes that they allowed for women. As for Krasner, by her second term in 1929, she was made a “monitor,” which helped to pay for her materials and other expenses. According to Slobodkina, monitors were usually chosen by the students in a class.65 But a teacher, if displeased, could surely replace the monitor.

Despite Krasner’s problems with the academy, her fellow students seem to have recognized in Krasner the qualities of common sense, leadership, and a practical nature, since they made her secretary of the Students’ Association even before she got into trouble. Careful minutes for November 11, 1929, remain on file: $327 profit, school dance; $227 taken out for “student’s show,” as well as $120, loaned to the students’ supply store, leaving an active balance of $20.

Krasner continued to study during both day and night classes with Olinsky. As the academy required, he conducted separate life classes for men and women. Krasner’s classmate Ilya Bolotowsky also liked Olinsky. He remarked years later that he thought that the National Academy: “was a very bad school…. The teachers were extremely academic, although Olinsky was not; he was sort of a modernist. I was considered a rebel and a bad example because I was experimenting in color, rather modest experiments but for the Academy it was wild. We were warned not to follow people like Picasso, Cézanne…because Picasso never learned how to draw and Cézanne never learned how to paint, and other advice of this nature.”66

The faculty that Bolotowsky described is also the one that continued to esteem Igor Pantuhoff, who also studied with both Neilson and Olinsky. They awarded him the Mooney Traveling Scholarship in spring 1930, enabling him to travel to study the old masters in Europe. The award meant a temporary separation for Pantuhoff and Krasner, who were already viewed as a couple according to May Tabak Rosenberg.67 With Pantuhoff gone, Krasner could focus on advancing her own career, which he encouraged.68

According to the 1930 federal census, even though Krasner was registered as “Lenore” at the academy, she gave her name to the census taker as “Lee,” having already adopted this nickname permanently during Cooper Union days; on April 11, she gave her age as twenty-one, which was correct, because she would not have her birthday until October. She had not yet begun her habit of lying about her age. She continued to include a second s in Krassner.

Though Krasner continued to serve as the monitor of the night class, she was not among the winners of bronze medals or honorable mentions that went to four of the female students in “Drawing from Life—Figure.” In November 1930, Krasner was again taking Life in Full, continuing under Curran by day and Olinsky by night. Her work as the monitor for the night class suggests that she got along well with Olinsky. That year Krasner also attended lectures in art history, and lithography and took Chemistry of Color. In the spring of 1931, she attended lectures on the history of architecture, stained glass, and mosaics; the latter would prove particularly useful.

With Krasner in Curran’s class in 1930 and 1931 was Joseph Vogel, a Polish-born Jewish immigrant, who lived with his family in the Bronx. Vogel’s family was also poor and struggling to make ends meet. By January 1931, the Depression hit hard, and his registration card noted: “Given time to pay; Entire family out of work.” Vogel and Krasner took a class in the fall of 1931 with a new instructor named Leon Kroll.

Kroll had just arrived at the academy and was teaching Life in Full. He was gregarious, short, Jewish, and he painted portraits, figures, and landscapes. But most important, he was sophisticated enough to admire and talk about Cézanne, which caused the students to view him positively as a more progressive teacher. They did not know that Kroll’s background included painting with the realist Edward Hopper in Gloucester in 1912, and, just before World War I, befriending the modernist artists Sonia and Robert Delaunay in Paris, who were already painting adventurous, colorful cubist-inspired abstractions. Vogel remembered Kroll as the “Bolshevik of the Academy,” which, considering Vogel’s politics, was a compliment.69

Krasner recalled that “when it was announced that Leon Kroll was coming to the National Academy, it was as if Picasso was coming.” But she soon found him to be “very academic and hostile.”70 Kroll, once ensconced at the academy, seemed to have forgotten the modernist colors of the Delaunays. Krasner recalled that “one day this model came in and she was wild, her face was white, her hair was orange, she had purple eyelids and black round the eyes. I was the class monitor, and booked her right away, even though she wasn’t exactly academy stock. Kroll came in and took one look at the model, and demanded loudly which one of us was the monitor. He came over, took one look at my painting and screamed, ‘Young lady! Go home and take a mental bath.’”71

Krasner had just seen the Matisse retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in the fall of 1931. Though her enthusiasm for Matisse would last a lifetime, not all the public was so positive. In his review of the show in Art News, Ralph Flint expressed real reservations about Matisse and his influence. “His sensation-seeking brush has quickened many a brother artist into new flights of fancy. He has served as driving wedge to weaken those stubborn walls that stand in the way of all insurgent investigation. And yet, withal, he has remained a brilliant but signally uninspired master.”72

Despite her newfound inspiration, disaster soon struck Krasner. A fire at her parents’ home in Greenlawn destroyed the house and most of the work she had produced to date. One of the only surviving items was her small self-portrait on paper, which she always kept with her after that. In later years, she had it hanging in her parlor. The fire could have been ignited by her father’s cigar, but the real cause is not known.

The fire and the economic loss it caused came at a time of great uncertainty for the Krasners and for Jews in America in general. With the house destroyed, Krasner’s parents were reduced to living in their garage as they survived in a weakened national economy that fostered the growth of anti-Semitism, nationalism, anti-immigration sentiment, and local hate groups.73 From afar, they witnessed the rise of Nazism in Europe.

In view of growing nationalism and its connections to anti-Semitism, it is not surprising that Krasner repeatedly said, “I could never support anything called ‘American art.’”74 She had no doubt seen the new Modern’s second show, “Paintings by Nineteen Living Americans,” and followed the discussion it elicited in the press. The critic Forbes Watson attacked the foreign-born (and Jewish) Max Weber for taking “no account of the American tradition” in his painting and for being tied to “European standards.” Watson denounced “American laymen,” for whom “the modernity of all art depends upon the degree of success with which it emulates painting in Paris.”75 At the same time, he defended Edward Hopper, John Sloan, Charles Burchfield, and Rockwell Kent against those who perceived “a disturbing conservative quality” in their work.

On a wave of cultural nationalism, the Whitney Museum of American Art was founded in 1930 and opened on Eighth Street in 1931. It would feature what some saw as a more parochial choice of American artists than the Museum of Modern Art. The Whitney was aware of its problem, but it was not always sensitive to the identity issues it raised. One of the museum’s earliest publications, a monograph on Edward Hopper by Guy Pène du Bois, described Hopper as “the most inherently Anglo-Saxon painter of all times.” This was actually a distortion of Hopper’s ancestry, which was half Dutch and part French.76

Krasner must have known that the artist Thomas Hart Benton and the critic Thomas Craven were not alone in denouncing immigrants, ethnics, leftists, and Jews, claiming that they were incapable of painting the “true American” experience.77 To many eyes, the Jews were not the same race as Anglo-Saxons; they were not technically “white.” They were still not allowed to join exclusive clubs, stay in restricted hotels, attend all schools, or live in certain areas. In her relationship with Pantuhoff, however, Krasner clearly hoped to transcend this inferior status.

Around this time the Depression was beginning to hit hard. This was the overwhelming issue that led Krasner’s classmate Vogel to join the Unemployed Artists Group in the summer of 1933. Some of Vogel’s fellow members, who already belonged to Krasner’s circle of politically radical friends or would soon, were Balcomb Greene and his wife, Gertrude “Peter” Glass Greene, as well as Ibram Lassaw (all of whom would remain lifelong friends); Boris Gorelick, Michael Loew, and Max Spivak, with whom Krasner would work on the WPA and in the Artists Union. This group of activists was formed within the John Reed Club, which was the main institutional base for Communist and fellow-traveling artists before 1935.78

Unemployment became an even more significant issue when landlords began to throw these workers and their families onto the street. On February 4, 1932, more than 3,500 unemployed workers braved cold rain to gather at Union Square and march in protest to City Hall. A group of Communist organizers told the board of alderman (city council): “Unless the city finds some way to prevent further evictions of the families of the unemployed, the Unemployed Councils of New York will use force to ‘fight off the hired thugs of the landlords.’ There are more than one million workers unemployed in New York City. The city is doing nothing to help them.”79

A month later, on March 6, 1932, a large group of artists gathered in Union Square. They called themselves the Unemployment Council and, for the first time, called attention to unemployment and poverty among artists. Their efforts led to the founding of the Artists Union. Krasner’s fellow student Boris Gorelick recalled: “It was not one of the first organizations, but it was the first amongst the cultural workers and subsequently played a very leading and very important role in, for one thing, bringing about recognition of the responsibility of government to the artist per se and also the need for unity amongst the artists for their own survival.”80

Krasner had always suffered from her family’s poverty, but at this time the harsh economy even impinged upon her ability to earn her own way through part-time jobs. Affected by the extreme poverty all around her and the bleak uncertainty for artists, Krasner left the academy in April 1932 and enrolled at the City College of New York on 139th Street and St. Nicholas Terrace in Manhattan, where tuition was free. Her purpose was to obtain a teaching certificate, which would allow her to teach art in high schools.81 She took Teaching in Junior and Senior High and Problems in Secondary School Teaching. At this time, she gave her address as 2511 New Kirk Street in the Ditmas Park neighborhood of Flatbush in Brooklyn. It was a long commute to upper Manhattan, where she was spending time with Pantuhoff.

City College was intensely intellectual and ideological in the 1930s. At the college on May 23, 1932, three thousand students, organized by the leftist National Student League, protested a fee increase for evening students. Ten thousand students signed petitions of protest, and the Board of Higher Education was forced to eliminate the fee. Although Krasner studied by day and worked at night, she can hardly have missed the night students’ successful protest. Like most of her peers, she was struggling to survive. Among the other students that year was the future playwright Arthur Miller, who attended for only three weeks before he too had to give up. He was not able to make the commute from Brooklyn, hold down his job in a West Side warehouse, and complete his assignments.82

Krasner later recalled: “I decided to do something practical about livelihood, so I took my pedagogy, so I could qualify to teach art. I got through with it—I took it at CCNY—did waitressing in the afternoons or evenings, did this work in the daytime. I got my pedagogy and decided the last thing in the world that I wanted to do was to teach art so I tore that up.”83 She didn’t finish the degree until 1935, so it was a considerable investment of time and effort that she eventually abandoned to pursue her long-held dreams of becoming an artist.

Krasner’s decision to drop teaching might also have been a response to the times and the increasing difficulty of obtaining secure teaching positions. For example, Barnett Newman, a 1927 graduate of City College, tried unsuccessfully in 1931 to become an art teacher in the New York City public school system after his family’s clothing business suffered from the stock market crash. Though he would later be famous as an abstract expressionist artist, he failed the exam for a regular teaching license and instead became a substitute art teacher, earning $7.50 a day, but only when work was available.

There was also Krasner’s experience working at night as a cocktail waitress at Sam Johnson’s, a bohemian nightclub and café, while attending college. Located on Third Street, between MacDougal and Thompson in Greenwich Village, Johnson’s was a spot where artists and intellectuals liked to congregate and where poetry was read. The talk there was stimulating. Lionel Abel once called Sam Johnson’s “a sort of proletarianized version of the Jumble Shop,” another Village eatery where Krasner spent time with other artists.84

Krasner reminisced, “They collected a great many bohemians who did special things like reading of poetry for discussions.”85

For her job, she wore the required work attire, Chinese silk “hostess” pajamas, and enjoyed socializing with the customers: “They would come in the evenings and discuss ‘the higher things in life.’ I was quietly in the background for a while and then I began to know them and I identified myself. But it was a short period while I was getting my pedagogy points at CCNY.”86

The club was co-owned by the poet Eli Siegel, described as having “a saturnine expression and the bent bearing of a yeshivah bocher,” and Morton Deutsch, a “defrocked rabbi.” Siegel, who once defined a poem as “A whirlwind with details,” liked to recite Vachel Lindsay’s poem “The Congo” as it was intended to be, read aloud, making a theatrical production out of its jazz-inspired rhythms. Siegel won The Nation’s poetry prize in 1926 and was the first American imitator of Gertrude Stein. According to Harold Rosenberg, Siegel “imitated Stein…quite well, too.”87

At this period Krasner may have intensified her interest in Emerson’s writings on the meaning of life and art.88 His work as a poet, essayist, and philosopher could have caught her ear either in the talk about “higher things” at Sam Johnson’s or it could have occurred during her classes at City College. The transcendentalism that Emerson expressed in his 1836 essay “Nature,” stressing an ideal spiritual reality over empirical and scientific knowledge, would have suited some of Krasner’s own sensibilities, which also relied upon intuition. Later, she titled a painting The Eye Is the First Circle, after the first line of Emerson’s 1841 essay “Circle.”

At Sam Johnson’s, Krasner worked not only for tips but also for dinner on the nights she worked. (In her later years, she continued to complain about the art critic Harold Rosenberg, who never tipped.)89 He later explained why he did not tip. “We didn’t [have] any dough, but we were more or less welcome because I suppose we provided local color or something…. The Sam Johnson was our hangout for quite a while. Lee [Krasner] Pollock used to be a waitress there.”90

“You see, we knew Deutsch, and he ran the place really; Eli was just sort of a semisilent partner. He would read poetry there. That was his main function. So it was understood that we have everything on the house,” rationalized Rosenberg, forgetting that Krasner still needed tips, even if he and his friends were feasting and drinking on the house. “So Lee would bring us sandwiches and coffee, or something. And once in a while we’d say to Deutsch, ‘Why don’t you get rid of these lousy bourgeois and go and get some booze, so we can have a real discussion here?’”91

The future art critic’s wife, May Tabak (Rosenberg), believed that the club presented good opportunities for college girls. “The women of Bohemia found themselves given a better break than men. Even at some unskilled jobs. An educated girl tended to make more in waitress tips than an equally good-looking ‘dumb’ one. Male customers were more anxious to impress the smart girls. Bosses of restaurants believed that college dames added class to their joints.”92

Krasner met a number of people who were also customers at Sam Johnson’s. Among them were Rosenberg’s brother, Dave, Lionel Abel, the film critic Parker Tyler, the writer and poet Maxwell Bodenheim, and Joe Gould, a Village character who is best known for the vernacular oral history of life around him that he claimed to chronicle.93 The Dial, then a sophisticated arts magazine, published his short essay called “Civilization” in its April 1929 issue. A legend in his own time, Gould appears nude in his portrait painted in 1933 by the artist Alice Neel.

Maxwell Bodenheim was successful and well known as the editor of the avant-garde poetry magazine Others, and as the author of the 1925 novel Replenishing Jessica, then characterized by some critics as cynical and indecent. In 1928, when Bodenheim was thirty-five and separated from his wife and child, he became notorious for his connection to twenty-four-year-old aspiring writer Virginia Drew. Like Krasner, but just a few years older, Drew had attended both Washington Irving High School and Cooper Union. She had solicited Bodenheim for career advice. Desperate after Bodenheim condemned her literary efforts, she committed suicide in the Hudson River shortly after she left his MacDougal Street apartment. A young woman who was her friend told detectives that the two had made a suicide pact, which Bodenheim denied.94 Press accounts also reported Virginia Drew’s complaint “that her mother did not understand her ambitions.”95

One newspaper also reported that, less than two weeks earlier, “a nineteen-year-old girl was found unconscious in her apartment in Greenwich Village. Gas was escaping from a stove, but the windows were wide open.”96 Gladys Loeb, who had studied at New York University, was rescued by her physician father, Dr. Martin J. Loeb, and taken home to the Bronx, having tried to kill herself after Bodenheim called her poetry “sentimental slush.”97 Even after Drew’s suicide hit the press, Gladys Loeb once again approached Bodenheim. By then he had fled to Provincetown, where Loeb’s father went in pursuit of his daughter, anxious that she too might again try ending her life.

Krasner was not as fragile as the young women who pursued Bodenheim. She always maintained that her parents were indifferent to her career choice as long as she made no demands upon them. Hence she was less vulnerable to judgments from powerful or established men in the art world. She had a healthy sense of her own ability and her work’s value, even if others initially failed to agree. She repeatedly brushed off her teachers’ negative criticisms and pushed ahead. Self-confidence and firm resolve were, in the end, more valuable than talent alone. Sometimes, when asked how she dealt with such issues, she would respond, “I guess that I’m just a tough cookie.”98