THIRTEEN

Coming Apart, 1953–56

Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner in his barn studio with their Springs neighbor Sam Duboff, August 1953. Pollock’s Portrait and a Dream is visible.

DURING THE SPRING OF 1953, IN THE MIDST OF HIS DRINKING binges, Jackson Pollock drove his Model A into the wrong lane of traffic on Main Street in East Hampton, forcing a motorist coming toward him off the road.1 During this period, he had been preoccupied with trying to shingle and winterize his barn studio so that he could work comfortably during the winter, making a considerable financial stretch to achieve this goal. That summer he devoted himself to painting, managing to produce major canvases despite his growing self-doubt.

In the summer of 1953, Pollock posed for photographs with Raphael Gribetz, the adorable infant son of Joel and Helen Gribetz, a doctor and his wife, who rented the house next door for the summer. Though Pollock was just forty-one, he grinned like a proud grandfather. He had been longing to have a child of his own. Lee was then nearly forty-five and no more interested in having a child than when they had married almost eight years earlier. For her, as she later made clear, Pollock was enough of a child.2 Both psychologically and economically, Krasner had felt that she did not have enough to share with yet another helpless human being. Nonetheless, Helen Gribetz found Krasner to be “a very giving person.” She still recalls how Krasner volunteered to take her family’s wash to the Laundromat, since she was taking care of her five children that summer. The Gribetz couple socialized with Lee and Jackson that summer, so much so that Helen recalls Lee as “a most gracious hostess.”3 Jackson too was helpful, taking the older Gribetz children to the beach.

At this time, it was not uncommon for women artists to choose not to have children, especially those women living in difficult circumstances. Krasner’s friend, Slobodkina, described the pressure that her former husband, Ilya Bolotowsky, put on her to have children: “My NO was clear and firm. I had enough to do with one child in the family; and besides I married him to become an artist, not a mother.”4 In Krasner’s case, she had already become an artist and married Pollock just two days before her thirty-seventh birthday, prepared to take care of his intensive needs, not those of a child.

Almost miraculously Krasner’s instinct for self-preservation emerged out of the chaos of Pollock’s self-destructive binges. She finally got her own separate studio, after they bought an acre adjoining their house on the north side and moved onto it a little shack, which had once been a smokehouse, for her to work in. Perhaps finally realizing what she was up against, and finding herself less and less able to help Pollock, she lost herself in her own work and made a new set of collages, recycling older work. She later said, “These were inspired by earlier drawings that I had torn, feeling somewhat depressed. The studio was hung solidly with drawings I couldn’t stand. 1953 was the deluge in this spurt of collage. It led to the exhibit at the Stable Gallery in 1955.”5

In many ways, Krasner’s work was a continuation of her studies. “Back in the ’30s as a Hofmann student, I had cut and replaced portions of a painting. I had also transposed a painting thinking I would put it into a mosaic form. There is a challenge in reshaping and re-adhering imagery from the earlier periods…. Well, there is a recycling of the self in some form.”

In East Hampton, Guild Hall held a summer group show of seventeen local artists. Though the organization had claimed eight years earlier that it was difficult to identify the artists in its community, New York Times journalist Stuart Preston commented, “It must have required considerable tact to choose such a comparatively small number from the large and energetic picture-producing community there, but those who made the grade should be well satisfied.”6 The artists, most of whom were now working abstractly, included both Krasner and Pollock, as well as James Brooks, Balcomb Greene, Alfonso Ossorio, Willem de Kooning, Elaine de Kooning, Wilfrid Zogbaum, and the realist Alexander Brook, who showed a romantic landscape.

Never a supporter of abstraction, Preston singled out “[Willem] de Kooning’s blithe and violent figures of women. As a pure sensationalist this artist has no equal here. There is much the same degree of energy in Jackson Pollock’s single canvas on which swirling tides of sullen paint encircle pockets of bright color.” Again, he criticized Krasner, saying that her “propeller and ribbon shapes in two contrasted colors are too sluggishly drawn to come off as they should.” She cannot have appreciated his comment, but at least he did manage to spell her name correctly.7

By mid-October, Pollock had become more and more dysfunctional as his binge drinking continued and his life spun out of control. Unable to paint and prepare for his next show on time, he had to ask Janis for “another advance” against sales. “Why the hell I let myself get in this position I don’t know—took off too big a bite on shingling the house I guess.”8 Janis had to postpone until the following February the show he had originally scheduled for November, because Pollock did not have a new body of work ready for it. The promised show, consisting of ten works, finally ran from February 1 to 27, 1954. Although Clement Greenberg did not review it, he was not silent. When he did express himself in 1955, he was pointedly negative: “Few of [Pollock’s] fellow artists can yet tell the difference between his good and his bad work—or at least not in New York. His most recent show, in 1954, was the first to contain pictures that were forced, pumped, dressed up, but it got more acceptance than any of his previous exhibitions.”9

In the spring of 1954, a troubled Pollock traded the art dealer Martha Jackson two of his black and white paintings for her green 1950 Oldsmobile convertible. He told Jeffrey Potter that he was thinking about letting Lee learn to drive on the Model A, “the clutch being almost gone, anyway.”10 Patsy Southgate, a newcomer to the region, had stepped in: “I took Lee’s side strongly from the point of view that ‘This Woman Is Not Being Treated Fairly.’ I mean literally. Lee had two pairs of britches to her name, was trapped in the house, and didn’t know how to drive. Jackson didn’t want her to, but he had mobility. He would go off, had this large studio, this person making delicious food, and pretty much what he wanted.”11

Southgate was a mother with two young children. She and her husband, the writer Peter Matthiessen, had only just arrived on Long Island the year before from Paris, where he had founded the Paris Review. Krasner and Southgate quickly became close friends. Krasner was attracted not so much to the younger woman’s legendary beauty as to her intelligence and the sophistication she had acquired in France. Southgate also understood what it meant to go through a difficult time. She offered to give Krasner driving lessons in return for painting instruction, though she quickly realized that she could not paint. And Krasner was having trouble learning to drive, which Southgate attributed to a lack of self-confidence: “She had to take her license test a couple of times, but she did get her license finally. Then she was liberated: She could go shopping, see friends, be on her own. Jackson didn’t like my teaching her at all; if you give people a car and a license, they have independence. I don’t think he wanted that.”12

The importance of driving to boost women’s confidence and as a remedy for inferiority complexes had been promoted at least since 1939, when an article in the magazine Independent Woman stated, “This consciousness and power that come with successful handling of an automobile might even prove an important antidote for personality quirks…. It can make us feel infinitely more important than managing an egg beater.”13 The notion that women who could master driving an automobile might achieve biological and psychological equality with men had pervaded popular culture. The thought of Lee driving fueled some of Pollock’s fears, exacerbating his deep insecurities as a man, as a driver, and as a painter.

Since her show at Parsons, Krasner had begun to work in black and white, using ink, gouache, and collage on paper, canvas, or canvas board. Her forms were biomorphic, yet the titles give nothing away. She showed with other women in “Eight Painters, Two Sculptors” that summer at the Hampton Gallery and Workshop in Amagansett.

Krasner also had a solo show of her Little Image paintings and some recent collages for only one day in August at the House of Books and Music, an East Hampton shop where her friend Patsy Southgate worked. The owners of the shop, Donald and Carol Braider, stored some of their stock in a place known as the “red house” in the nearby town of Bridgehampton, which that summer a group of artists including the de Koonings rented. Pollock drove over one June day, hoping to visit with Franz Kline and de Kooning. They were all drinking and horsing around, when suddenly Pollock was on the ground with a broken ankle.

“He was absolutely indignant,” Elaine de Kooning said.

“He said: ‘I’ve never broken a bone.’”

The accident forced Pollock to abandon “that ridiculous little car of his there.”14

Pollock painted little during this year. He was filled with doubt. Matthiessen, who saw him during this period, described Pollock as “wonderful in many ways” and “calm if not plastered,” but recalled that he appeared to have “a hand grenade in his pocket” that could go off at any time.15 Even though the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (formerly the Museum of Non-Objective Painting, founded by Peggy’s uncle) acquired Pollock’s 1953 painting Ocean Greyness in November 1954, the sale to a museum did little to assuage his deep-seated doubts about himself. His drinking continued to increase.

Meanwhile Clement Greenberg definitively ended his relationship with Helen Frankenthaler in April 1955. Though he had written negatively about Pollock’s last show, Krasner still welcomed him in Springs several times. Greenberg came because he hoped to see his new psychotherapist, Ralph Klein, who was vacationing with his colleagues nearby at Barnes Landing, an East Hampton community that bordered Springs on the east.

While at Springs, Greenberg sided with Krasner against Pollock’s worsening alcoholism. “That summer they were fighting all the time and I’d be there…. Well, I thought, ‘Why don’t you get out?’…She had this drunkard on her hands. I don’t like calling Jackson a drunkard, but that’s what he was. He was the most radical alcoholic I ever met, and I met plenty.”16

Krasner was still recovering from a severe attack of colitis from a year before. According to Greenberg, the illness changed her: “Before Lee got sick she was pretty intense; always talking about art. What do we think of this? What do we think of that?…Now Lee, I’d always had respect for. She was formidable; made of steel. And so competent at everything, except not the business head she was reputed to be…. Then when she was soft after her colitis, she didn’t give a shit anymore, for a while. It was delightful that she didn’t give a shit about what she thought about art. That was all off, she thought about life…. Jackson couldn’t stand it. I’ll go on record here. That’s when he began to turn on her. It wasn’t so much attacking her as rejecting something.”17

When Greenberg saw Pollock drinking and in a rage at Krasner, he suggested that she see either Ralph Klein or the psychiatrist Jane Pearce, who was Klein’s colleague. Both were still associated with the William Alanson White Institute, which continued the teachings of Harry Stack Sullivan after his death in 1949. Sullivan, an American follower of Freud, had emphasized the importance of parent-child relationships. His so-called followers, known as “Sullivanians,” were led by Pearce’s husband, Saul Newton.18 The group has been labeled “blasphemous” for invoking Sullivan’s name and for encouraging the severing of all family ties.19 In Newton and Pearce’s 1963 book, Conditions of Human Growth, they argued that the nuclear family prevented individual growth and creativity and they advocated breaking such ties.20 Their activist form of therapy advocated new “growth experiences.” It must be noted that Newton only had a B.A. degree.

The day after talking to Greenberg, Krasner took his advice and was referred to Leonard Israel Siegel, another Sullivanian colleague. Unlike Saul Newton, Siegel actually had professional training, including a degree in medicine from Johns Hopkins University and a residency in psychiatry at Bellevue Hospital in New York. He purported to be a disciple of Sullivan, but his close association with Pearce and Newton suggests that his therapy then diverged from Sullivan’s teachings as theirs did.

In one published paper, Siegel wrote: “The role of successful psychotherapy is to enlarge the scope of the self, as previously dissociated and selectively unattended aspects of self can be reintegrated.”21 He contended that “for Sullivan, anxiety and its avoidance are central motivating forces…. There is a drive toward relatedness with other people and toward seeking their approval and avoiding their disapproval…. Mental illness is seen as an attempt to solve interpersonal problems, especially those created by pathology in parents and in the larger social surround.”22 This latter reference to pathology in parents recalls the “Sullivanian” cult’s attempt to get their followers to cut off from their families and close friends. Siegel’s therapy might later have motivated Krasner to break off completely with close friends such as Fritz Bultman and B. H. Friedman.

Not enough is known about how long Siegel stayed affiliated with the Sullivanians; however, his widow confirms that he was affiliated with both the Sullivanians and, earlier, with the William Alanson White Institute in New York.23 Without knowing the extent of Siegel’s involvement with the Sullivanians, it is impossible to reconstruct his therapy for Krasner and its effect. What is known is that Siegel’s own analyst was Clara M. Thompson, who was a cofounder of the William Alanson White Institute and a close friend of Harry Stack Sullivan. Thompson wrote papers on the role of women, including “Some Effects of the Derogatory Attitude toward Female Sexuality” (1950), the latter around the time that Siegel was training with her.

Siegel developed a deep interest in the arts “as a vehicle to the unconscious and encouraged his patients to paint, draw, compose, etc.” He also got some of his patients to paint with him. It is not certain how long Krasner stayed in therapy, since Bob Friedman says her therapy with Siegel ended in July 1958.24 Yet her nephew’s ex-wife, Frances Patiky Stein, recalled that Lee was still seeing “that maniac doctor” Siegel in the early 1960s.25 Stein said that Siegel was “insane, off the wall.”26

Krasner’s friend Cile Downs remembered going over to Len Siegel’s place at Barnes Landing with Krasner for a cookout. She observed that “Siegel, like Jackson, wanted Lee to coddle him.” She also remarked that he was one of the Sullivanians who “believed that therapists slept with their patients.”27 Clement Greenberg commented that Siegel became so dependent on Krasner that he came to see her to be comforted, a fact that caused her to give up on him as her therapist.28 Greenberg asserted that the Sullivanians, the followers of Saul Newton, also gave up on Siegel as a result, but added that he understood how someone could “succumb” to Krasner’s strength.29

Krasner was at least partially aware that what she got was not just the orthodox teachings of Harry Stack Sullivan: “I had one year of analysis at the time I painted Prophecy. It was a splinter group from the Sullivan school and if one must separate Jung and Freud, this would be in the direction of Freud.”30

Not to be left out, Pollock entered weekly analysis with Ralph Klein in New York City in the fall. He tried to get three sessions into two days, and while in the city, he stopped regularly by the Cedar Bar.31 He was stuck in a period of heavy drinking and artistic inactivity. Klein later spoke about having Pollock as his patient, telling how the artist came blustering in and said that therapy was all “a bunch of shit,” and how he had to tell Pollock to shut up and be seated. He admitted that he usually found Pollock drunk, and, although he was unable to stop Pollock’s destructive behavior, he did not seek other help for him.32

Ben Heller, a young businessman and art collector who had befriended Pollock, recalls that Pollock would often telephone him on Tuesdays, when he was recovering from a binge the night before, after his appointment with Klein. Heller became so concerned that Pollock was not getting enough nutrition that he telephoned Klein, who reassured him that beer was very nutritious.33

Klein’s treatment of Pollock’s problems ignored his alcoholism and was otherwise quite unorthodox. Klein left the William Alanson White Institute at the time the American Psychiatric Association refused to sanction training of nonmedical psychoanalysts, joining Newton in the Sullivanian Institute for Research in Psychoanalysis, which was founded in 1957. As a follower of Pearce and Newton, Klein became one of four leaders in their new radical therapeutic community on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. They moved on from Sullivan’s idea about the critical significance of interpersonal relationships to declare them harmful, even encouraging patients to break all close ties. The founders of the new group believed that they were the germ of a new society that would permit freedom from repression and obligation that kept people from personal fulfillment and creativity. The group eventually turned coercive and totalitarian, with the therapists wielding enormous power over the lives of patients and group members.34

Klein’s circle did not consider monogamy acceptable—anyone could choose to have a child and might get permission to do so with anyone, not necessarily a spouse. Klein encouraged Pollock to have an extramarital affair. This would at least allow him to fulfill his desire to have a child. Pollock was completely under Klein’s spell. Patsy Southgate often took the train with Pollock to or from New York when he was going to his appointments.

“He never wept on the train going in—he was always frightened then—but coming out there would be tears, and I felt it was genuine when he wasn’t drunk,” Southgate recalled. “The therapy situation was very frustrating for him, the not being understood or thinking he wasn’t. He had a complete transference with Klein and as with all transferences, a sort of godlike quality was attributed to him. I would think, ‘Lord I hope this guy realizes what he’s doing and what’s brewing inside Jackson’s head.’”35

Another one of Klein’s patients, the singer Judy Collins, wrote about her therapy with Klein several years later: “I told Ralph that I thought I had a problem with alcohol. Ralph, to my relief at the time and horror later on, did not agree. He said that we would work on the underlying trouble and not to worry about my drinking…. Ralph was quite comfortable recommending alcohol for anxiety.”36 The Sullivanians were not up-to-date in their treatment of alcoholism, which required abstinence. Instead they focused on interpersonal relationships. Along with the other Sullivanians, Klein “did not think people should be in monogamous relationships or live with anyone exclusively,” recalled Collins, who explained their interest in encouraging creative individuals “to break down the isolation they thought people acquire in a oneon-one relationship in which each partner becomes dependent on the other for everything.”37

Klein was clearly not up to the task of treating Pollock, who was already struggling with so much pain, and must have only confused him. “Dr. Klein had said it was all right for Jackson to drink and drive,” Krasner later told a stunned Jeffrey Potter.38 It was a treatment that proved fatal—as Patsy Southgate later said, “I think Ralph Klein killed Jackson.”39 What Krasner probably failed to grasp was that Klein pushed Pollock to break his bond with her.

Decades later, the New York State Board of Regents forced Klein to surrender his license. Many considered the Sullivanian Institute to be a cult because it was said to permit sexual relationships between licensed psychologists and their patients, to foster the use of controlled substances, to promote the destruction of family relationships, and to commit other violations of professional standards.40 It may be that Siegel, Krasner’s therapist, wanted to escape this coterie, since he eventually moved all the way to Australia.

Krasner kept papers on which she wrote down one of her dreams for her therapist. She noted, “J. [Jackson] better but still very disturbed—went to bed and he tried to talk to me about getting closer—said he appreciated my staying with him.”41 The next day she notes, “Friday. J. almost out of state.” Clearly she was struggling to deal with her deeply troubled spouse and it was taking its toll. Later she spoke of being in a perpetual state of crisis with Pollock.42

Their friends were also concerned. Sheridan Lord, the painter, and his wife, Cile (Downs), had met Krasner and Pollock at the home of Peter Matthiessen and Patsy Southgate, when Pollock’s alcoholism was acute. Although Krasner had begun to rely on the Lords to help keep track of Pollock, they were not able to prevent him from drinking or to prevail upon him to go home with them.43 Cile recalled that if tea was given to Pollock, he would pour whiskey into it. She said that Krasner was always calm and permissive, and that “she hadn’t had any therapy about drawing the line yet.”44 At the time, she said Lee was “cute and lively” with a “poodle haircut.”45

But according to Cile, once Krasner entered therapy, her behavior toward Pollock changed. She no longer functioned as his enabler, having learned about what we would now call “tough love”—and that put Pollock in a rage. Once Pollock bought roses, Cile remembered, and gave each one of them to various women in East Hampton, including Cile. Lee’s nephew Ronnie Stein, who saw a lot of his aunt and uncle, commented, “Lee had loved Jackson intensely, the way a young girl would love a hero: as a man, as an artist, as an image. The difficulty began when her physical and mental strength began to break down, and she became less and less capable. Then deadly alcohol changed love to drudgery: Jackson left boyish pranks and carryings-on—that polarity from being mystical to being boyish—for going down. There was an unholy alliance! He might have been a genius, but he was also a common drunk.”46

BY 1955, KRASNER HAD TO LOOK TO HER OWN WORK FOR SOLACE. She must have determined not to let Pollock pull her down with him into the abyss. The critic Eleanor Munro has characterized some of her collages of 1955 as “fiercely vertical compositions with titles expressive of a will not to lie down: Milkweed…Burning Candles.”47 Krasner remarked, “The fact that he drank and was extraordinarily difficult to live with was another side…. But the thing that made it possible for me to hold my equilibrium were these intervals when we had so much.”48 That her love for Pollock had become self-destructive was difficult for her to accept.

Krasner had a solo show at Eleanor Ward’s Stable Gallery from September 26 through October 15, 1955. The gallery took its name from its first home, a former livery stable on Seventh Avenue at West Fifty-eighth Street in Manhattan. On view were a group of collages of paper and cloth attached to painted supports of pressed wood, stretched linen, or cotton duck, at least some of which were unsold works from her 1951 show at Parsons.

STUART PRESTON FINALLY WROTE A FAVORABLE REVIEW FOR THE New York Times: “In Lee Krasner’s collages at The Stable Gallery, we find ourselves in the midst of a dense jungle of exotic shape and color. The eye is fenced in by the myriad scraps of paper, burlap and canvas swabbed with color that she pastes up so energetically. She is a good noisy colorist, and some of the larger pictures would agreeably animate many an antiseptic modern interior. For their principle is verticality which they both exemplify and communicate.”49

The painter and art critic Fairfield Porter wrote in Art News that some of her largest collages “with titles like Stretched Yellow, Milkweed and Blue Level, are like nature photographs magnified…. Krasner’s art, which seems to be about nature, instead of making the spectator aware of a grand design, makes him aware of a subtle disorder greater than he might otherwise have thought possible.”50

In Arts, the critic and art historian Martica Sawin worried that “the assets of making paintings with paper and cloth instead of, or in combination with pigment, are not clear since the immediacy of touch and stroke are lacking and only the decorative effects remain.”51

The gallerist Eleanor Ward was the same age as Pollock and was a person of “taste and flair.” She had come to art from the world of fashion, having worked for the designer Christian Dior in Paris. She came from an “Episcopalian social-register background,” recalled Alan Groh, who worked as her gallery assistant from 1956 to 1970—she once told him, “I would not have hired you if I’d known you were a Jew.”52

Thus she probably considered Krasner provincial, ill mannered, and downright pushy. “This very strong woman was not easy to work with,” Ward said of Krasner. “I told her that I thought it was a good time for me to select her show. She said ‘You select my show? I am selecting my show and I am hanging it on both floors.’ So I answered, ‘Lee, then there will be no show, unless it is on one floor and I select it.’ That’s the way it ended because she wanted a show. And I realized that if I once let her gain control over me, I would just be putty.”53 But Ward, who was said to be proud of her “eye,” never allowed artists to be present while she installed their work on her gallery walls.54

Ward later wrote to the sculptor Wilfrid Zogbaum, whom she also represented, to complain about Krasner’s “high temperament” and that she had left the Stable Gallery for Martha Jackson’s.55 Krasner can hardly be blamed for rejecting Ward’s controlling nature and limited enthusiasm to find a better dealer. Yet Zogbaum replied bluntly and sympathetically toward Ward: “Was sorry to hear about your difficulties with Lee Krasner but it did not come as a great surprise. Although she has been a friend of mine for twenty years there is that extreme ambition in her that is at times a bit frightening. One doesn’t know whether to admire or despise it.”56 Zogbaum was certainly not the first man to react against Krasner’s remarkable enterprise, but one can hardly imagine that Zogbaum would have been so frightened if Krasner had been a man.

One night Krasner had invited Ward to dinner at her house. Ward recalled, “The relationship [between Jackson and Lee] was very, very curious. Once at dinner there was a bowl of peaches Lee had made, which Jackson wouldn’t touch. She said, ‘Now Jackson, they’re good for you. Eat them.’ He picked up a spoon like a child being told what to do.”57 Ossorio also commented about the “maternal aspect” in their relationship, “the way she treated him like a child and he hating it.”58

The younger artist Nicolas Carone, who shared with Krasner the experience of having studied with both Leon Kroll and Hans Hofmann, felt he understood what their relationship was about: “She took care of him; you don’t let go of a Jackson. You have to watch him every minute, and more; a woman taking care of such a man is not just feeding him and darning his socks; she’s living with a man who might flip any minute. Think of the tensions she lived under! Lee knew she was dealing with a powder keg.”59

Dan T. Miller, the proprietor of the General Store in Springs, not far from the Pollocks’ home, recalled: “I’ve seen him drive up here to these gas pumps for gas and get in and drive away with Mrs. Pollock sitting beside him, and I wouldn’t have sat beside him in that condition he was in but she did. There was a quality of love or however you want to put it. But the point I wanted to make is that she didn’t just get up and run when things got a little bit rugged. She sure didn’t. I thought to myself more than once ‘Well Lee I wouldn’t drive with that son-of-a-gun—I’d get up and walk off’ but she didn’t.”60

Pollock’s mother, Stella, suffered a series of heart attacks in late November 1954. Soon after, Lee went with Jackson to see Stella at Sande and Arloie’s home in Deep River, Connecticut. At Christmas they returned. Lee offered to have Stella come and live with them in Springs, thinking that Stella might help save Jackson, but Arloie refused, citing Stella’s age and condition: “Jack didn’t have anything to help her with. He and Lee were not in a very happy situation and she [Stella] didn’t need that aggravation; the strain would have been huge.”61

Pollock became more and more desperate as he became less able to paint. In 1955 he told his homeopath, Dr. Hubbard, that he had not painted for a year and a half because he wondered if he was saying anything.62 In the middle of February, he broke his ankle again, this time wrestling with Sheridan Lord. Jackson had challenged Sheridan on his own living room floor. Sheridan’s wife, Cile, recalled that “Lee had been trying to get him not to, and he knew his bones were brittle…. It was such a dumb thing to do, I wasn’t even sorry for him.”63 But Cile was sorry for Lee. “It was hell. I thought that we were going to lose Lee. She got thinner and thinner.”64

Things got slightly better in 1956. Pollock told Dr. Hubbard that he felt better even though he couldn’t “stand reality.”65 In the early spring of 1956, the painter Paul Jenkins saw Pollock at Clement Greenberg’s on Bank Street and encouraged him to come to Paris. Pollock protested, saying, “It’s too late for that.”66 He was just forty-four.

In April Greenberg arranged for Jenkins and two other abstract painters, the German-born Friedel Dzubas and Alan Davie (then visiting from Scotland for his show in New York), to stay in The Creeks and meet Pollock. Krasner cooked lunch for them. Jenkins said her cooking was “extraordinary.” He recalled that Pollock was sober, and that he drove the two of them out to Montauk Point, the scenic spot at the end of Long Island.67 Jenkins knew that Pollock’s work was admired in Paris, and he invited Pollock and Krasner to come there and see him and his wife. Jenkins had no trouble interesting Krasner, but he had trouble with Pollock. Nevertheless he applied for a passport, and then never used it. Perhaps he only got the passport to appease Lee.

One day Krasner recounted to Jenkins how she had gone to her therapist to talk about “one of the most terrifying nightmares anyone has ever told.” After the session, when she returned to Jackson, “he turned white when he saw her. He walked up to her and clasped both of her hands and they sat down together. ‘What happened Lee?’ ‘Jackson, please, I am all right.’ ‘Please tell me. You are completely different!’ Lee went on to explain Jackson’s astonishment, and how she could not get over it.”68 Jenkins explained that what took place in Krasner’s therapy session could be “compared to a kind of exorcism. A kind of monster that had dwelt in her childhood had dissolved, vanished—and Jackson knew it, he did not just sense it. In Lee’s dream, a frightening total monster lived in her cellar when she was a child, and it was real in her psyche, not her imagination.”69

At one point during his stay Jenkins witnessed Jackson shoot an arrow into the wall of the kitchen in his Springs house. After leaving the house, Jenkins sent Jackson and Lee a gift of Zen in the Art of Archery, a book written by the philosopher Eugen Herrigel in German and first translated into English in 1953. Jenkins wrote, “Again many good thoughts for the weekend spent with you both. Here is the archery book and Esther & I hope you enjoy reading it. Before returning to Paris I hope we will [have] another chance to talk—if we don’t however it has been a real joy to have visited and will remember always your generosity.”70

After receiving the book, Krasner wrote herself a note: “I want to talk about my self destruction my disgust & stupidity—(waiting—paralysis) waiting—& trapped by…Zen & the mastery of Archery…began to breathe more easily & dove in—point I made about painting—let it come to me.”71 In her desperate search for inner peace in the face of Pollock’s turmoil, Lee had been thinking about Zen concepts.

Krasner’s fear was surely related to the disquieting presence in the painting she was working on in the summer of 1956: “The painting disturbed me enormously and I called Jackson to look at it. He assured me it was a good painting, and said not to think about it, just continue—do another one. Not tie into what my reaction to it was, the way I was doing.”72

Krasner ignored Pollock’s suggestion that she remove the disembodied eye scratched onto the dark upper right corner of the composition. The painting, which she later titled Prophecy, always chilled her: “In that sense the painting becomes an element of the unconscious—as one might bring forth a dream.”73 Even Eleanor Ward, upon seeing the painting before it was ready, commented, “God, that’s scary.”74 Krasner described this canvas as “a break in color as well as imagery” and said, “I think I felt when I did the painting, it was Prophecy, as it was a new theme.”75 Alfonso Ossorio recognized how significant this canvas was and purchased it.

Meanwhile Pollock’s reputation was carrying him along, even though he was no longer productive. In May, the Museum of Modern Art told Pollock that he would be featured in a solo midcareer show of twenty-five works, the first of a series of shows of “Work in Progress.” That June Pollock said in an interview, “I don’t care for ‘abstract expressionism’…and it’s certainly not ‘nonobjective,’ and not ‘nonrepresentational’ either. I’m very representational some of the time, and a little all of the time. But when you’re painting out of your unconscious, figures are bound to emerge. We’re all of us influenced by Freud, I guess. I’ve been a Jungian for a long time…. Painting is a state of being…. Painting is self-discovery. Every good artist paints what he is.”76 By this time, however, Pollock had serious doubts as to what he was.

Hoping to cheer up Pollock, Krasner invited Charlotte Park and Jim Brooks for dinner on June 18, 1956. Charlotte wrote in her journal, “Went to Pollocks for dinner last night. Had invited them here but Jackson’s going through another bad spell…. Jackson is in bad shape but went to bed about a half-hour and when he got up was much more coherent.”77

Back in New York, at the Cedar Bar, Pollock ran into Audrey Flack, an ambitious young painter then just twenty-five, who recalls seeing him earlier at the Artists Club on Ninth Street. Flack recalls that she went to the Cedar alone, hoping to meet her heroes, including Pollock, de Kooning, and Kline. When Pollock approached her at the bar, however, she describes how he tried “to grab me, physically grab me—pulled my behind—and burped in my face…. He was so sick, the idea of kissing him—it would be like kissing a derelict on the Bowery.”78 She was so appalled that she never again visited the Cedar.

Shortly after her encounter with Pollock, Flack met Ruth Kligman, a stunningly beautiful young woman who had just moved to the city from New Jersey and was working for $25 a week as an assistant at the obscure Collector’s Gallery. When Kligman asked her for the names of important artists she should meet, Flack replied, “Jackson Pollock, Franz Kline, or Bill de Kooning.” “She asked which one was the most important,” Flack recalled, “and I said Pollock; that’s why she started with him. She went right to the bar and made a beeline for Pollock. Ruth had a desperation and a need.”79 She was a “star-fucker,” commented Flack, using the word “star” as a noun and object of the verb.80

Accounts have variously described Kligman as endowed with “an Elizabeth Taylor aspect” and as “coquettish” during the time she ensnared Pollock at the Cedar.81 Patsy Southgate said that she and Jackson “talked a lot about Ruth and we talked a lot about Lee; he was very excited about Ruth and terribly afraid of Lee, desperately afraid of Lee…. He viewed the whole thing as an amazing adventure; he wondered if he could pull it off with Lee, keep Ruth going along. Like a little boy, his dream was to have both.”82

Ruth was “an art bobby-soxer,” said Carol Braider, who had showed Krasner’s work at her House of Books and Music. “As for the ‘Lee doesn’t understand me’ line he handed out, most of us would say, ‘Oh fuck off, Jackson!’”83 B. H. Friedman, who met with both Krasner and Kligman during this period, described Lee as “lively, talkative, gregarious” and Kligman as someone who told Pollock in his dissipation that he was “still alive.”84 Ossorio considered Pollock’s relationship with Ruth to be “pathetic…a young girl throwing herself at his feet.”85

Kligman sensationalized and capitalized on her time with Pollock in a 1974 memoir called Love Affair.86 She wrote that she would tell him that he was married and that she had to “make a life” for herself and that Pollock would argue against this by insisting, “My analyst says the opposite. That we’re good for each other. I told him all about you, and he encouraged me.”87 She claimed more than once that Pollock told her of his analyst’s support for their relationship. Kligman also asserted that Jackson questioned her about her grandparents—the kind of stock she came from—telling her that he planned to marry her and suggesting by this interest that he fantasized about having a child with her. Not surprisingly, these reports are consistent with Ralph Klein’s reputation—one that led to his losing his license to practice.

The affair became intolerable for Lee when Jackson got Ruth to spend the night in his studio with Lee not far away in their house. She gave him an ultimatum to stop seeing Ruth and announced that she was going to take the anticipated trip to visit the Jenkinses in Europe in three days and would return in three weeks. Both of them would have time and space to consider their future.

Krasner’s bold actions forced Pollock to reconsider his impetuous affair. According to the Pollocks’ neighbor, the painter Nicolas Carone, “He went through the act of getting rid of Lee to bring in Ruth with the romantic notion of filling in a moment in his life, an interlude and then realized it was shit. Also, he realized that he needed his wife, so he’d staked all on a move that didn’t have any substance. Lee understood the psychotic problems and knew he was miserable. And she knew that the real value of his work was more important to her than it was to him.”88

Pollock’s realization perhaps caused him to then turn against Ruth. A number of friends later noted that Pollock misbehaved with Ruth as he had with Lee. Charlotte Brooks commented that “Jackson was pretty tough with Ruth,” and Cile Downs reflected that she couldn’t “imagine Jackson and Ruth being a couple for long, and he was hostile to her—really rude, mean to her—although I never saw any physical violence.”89

When Krasner left for Europe in July, it was intended to be a trial separation, but it upset them both. “While she was in Paris,” Jenkins recalled, “[Lee and I] saw painters, met old friends like John Graham at the Deux Magots…. Maybe if Jackson had gone to Paris, it might have turned him around.”90

In a Paris café, Krasner chanced upon Charles Gimpel, an art dealer whom she had hoped to see in London. He invited her to visit his home in Provence in the south of France, expanding her plans.91 Gimpel had been hoping to arrange a show of Pollock’s black-and-white work at his London gallery. Lee wrote to Jackson from Paris on July 21:

I’m staying at the Hotel Quai Voltaire, Paris, until Sat the 28 then going to the South of France to visit with the Gimpel’s [sic] and I hope to get to Venice about the early part of August—It all seems like a dream. The Jenkins, Paul & Esther, were very kind, in fact I don’t think I’d have had a chance without them. Thursday nite ended up in a Latin quarter dive, with Betty Parsons, David [Howard], who works at Sidney’s, Helen Frankenthaler, the Jenkins, Sidney Geist & I don’t remember who else, all dancing like mad. Went to the flea market with John Graham yesterday—saw all the left-bank galleries, met Druin and several other dealers (Tapié, Stadler etc.) Am going to do the right-bank galleries next week. I entered the Louvre which is just across the Seine outside my balcony which opens on it. About the Louvre I can say anything. It is overwhelming—beyond belief. I miss you and wish you were sharing this with me. The roses [that he sent to her] were the most beautiful deep red. Kiss Gype [sic] & Ahab [their dogs] for me. It would be wonderful to get a note from you. Love Lee—The painting here is unbelievably bad. (How are you Jackson?)92

Krasner later recalled the impact of seeing Chartres Cathedral and the old masters in the Louvre, which interested her much more than the contemporary art scene in Paris: “three paintings that stopped me dead in my tracks, and that startled me more than anything else because I didn’t expect these would be the paintings that would knock me off my track, so to speak. They were not what I expected them to be.”93 She recalled that the paintings were Uccello’s The Battle of San Romano (c. 1435–40), Andrea Mantegna’s St. Sebastian (c. 1480), and Goya’s La comtesse del Carpio, marquise de La Solana (1794–95).94 She was in awe over the latter. “The Goya is all spirit; you know, it simply leaves the earth.”95 Krasner also told how much she was interested by Ingres, whose style had captivated Browne, Gorky, Graham, and de Kooning during the 1930s.

From the old masters in the Louvre, she traveled to the narrow streets and medieval houses of Ménerbes, a lovely village in the Vaucluse. At the home of Charles and Kay Gimpel, Krasner found the artist Helen Frankenthaler.96 Krasner also visited the art historian Douglas Cooper in Menton on the Côte d’Azur, near the Italian border.

On July 26, Kay Gimpel wrote to Peggy Guggenheim, telling her that Lee was staying with her and that she wanted to go to Venice at the end of July or the beginning of August, before she sailed home on the twenty-third of August. Lee wanted to see Peggy in Venice and she was requesting Peggy’s help in booking a hotel.97

Krasner sent a postcard from Ménerbes back to Paul and Esther Jenkins in Paris: “The house is unbelievably 11th century perched on the top of a hill with views quite out of this world—Taking motor trips out to Arles, Aix, Marseilles, St. Remy etc. We’ll be here until about the 6th and then on to see Peggy—and back to you. Hope your time is moving pleasantly. Love, Lee.”98

When Krasner followed up on Kay’s letter, and called Peggy from the south of France to ask about reserving a hotel room, Peggy replied that she was too busy to see Lee and could not recommend a place for her to stay.99 This confirmed Krasner’s feeling that Peggy disliked women. Krasner thus decided to return to Paris. Her hotel was no longer available, so she decided to stay with Paul and Esther Jenkins at their place on the rue Decrès on the Left Bank.

Just after Lee returned to Paris, on Sunday, August 12, Paul Jenkins received a frantic phone call from Clement Greenberg in New York, who was trying to locate Lee. The news was bad. On August 11, at 10:15 P.M., while speeding north on Fireplace Road toward home, Pollock crashed his car into a clump of trees and flipped over. Of the car’s three occupants Ruth Kligman was injured, but a friend of hers, Edith Metzger, and Pollock were killed. Pollock suffered a compound fracture of the skull, laceration of the brain and both lungs, hemothorax, and shock. He was forty-four years old. Krasner was now, at forty-seven, a widow.

Krasner processed the news for a moment and then “she got up from the couch and screamed, ‘Jackson’s dead!’” recalled Jenkins.100 “We were living on the sixth floor, and she headed toward an open balcony; I reached out and grasped her. I placed her to the wall and didn’t let her go until she calmed down.” Jenkins contacted Darthea Speyer, the U.S. cultural attaché, who arranged for Lee to fly to New York that same night, where she would be met at the airport by the artist Barnett Newman and his wife, Annalee.

Before flight time, Esther Jenkins packed Krasner’s bags, and Paul drove Lee around Paris, even recruiting the assistance of Helen Frankenthaler, who also had come back to Paris.101 They stopped at the Bois de Boulogne and the Luxembourg Gardens to help pass the time.

The front page of the New York Times reported: “Mr. Pollock’s convertible turned over three miles north of East Hampton, according to witnesses. The accident occurred shortly after 10 P.M. on Fireplace Road. A woman riding in the car was killed and another woman, identified by Southampton hospital authorities as Ruth Kligman, was injured. The police were unable to determine the cause of the accident, but said the automobile had smashed into an embankment.”102 This article continued with a discussion of who Pollock was and what he was known for, before explaining, “Mr. Pollock was married to Lee Krasner, an established painter in her own right. Acquaintances here said that she was now in Europe.”103

The funeral took place on Wednesday, August 15, at the Springs Chapel, down the road from their house. Barnett and Annalee Newman paid for Pollock’s funeral, since Krasner had only $200 in the bank at that moment.104 Peter Matthiessen said that Lee asked him to take care of their dogs at the funeral. Pollock was then buried in Green River Cemetery, nearby in Springs. Jackson’s mother and brothers attended the funeral. Lee’s nephew and her sister also came, as did friends such as John Little, Reuben Kadish, Gina Knee, and Jim Brooks.

Krasner asked Clement Greenberg to speak at the funeral, but he refused, because of Pollock’s role in the death of Edith Metzger, though he did go to the funeral. Years later, Greenberg commented about the impact of Pollock’s death on him personally, saying that he thought more of him “as a man at the end and as a friend, even more than as an artist. I minded that girl getting killed with him and I wasn’t going to get up and speak about Jackson. Lee had hysterics over the phone. I wasn’t going to get up there and lie. I thought Jackson went out in a shabby way.”105

Another time, Greenberg said: “Lee was the one who really got to him and she was right. He could talk about art only with her—well, he could with me mostly when Lee was there to join in…. Art was his justification as a human being, because he felt inadequate in other respects. But Lee was his victim in the end, and a better painter than before.”106

A few nights after the funeral, the Sullivanian therapist Saul Newton, who spent summers with his disciples at nearby Barnes Landing, called on Krasner in Springs and recounted that “Lee was carrying on like an old-fashioned mourner. Franz Kline was there and she was blubbering ‘Help, help’ at him. About midnight she had to visit the cemetery, so I took her and Patsy [Southgate] there. It was a dark night and I told Lee she would have just one minute. Then I told her when her time was up, got them back, and left her in Patsy’s hands as a nightwatch. She slept off her grief and in the morning was in okay shape.”107

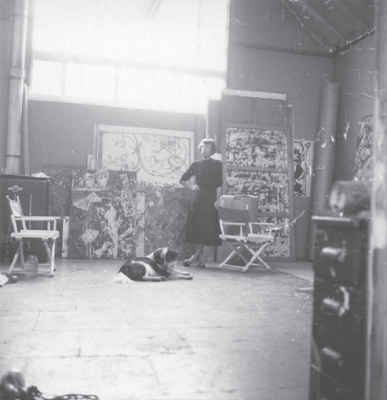

Lee Krasner with their dog, Gyp, in Jackson Pollock’s studio, two days after his burial, August 1956, photographed by Maurice Berezov. One of Krasner’s first preoccupations as a widow was supporting Pollock’s scheduled exhibition at MoMA, which turned into a memorial retrospective. Having lost him, she was determined not to let his legacy get away from her.

It was an ironic and tragic twist of fate that Greenberg—Pollock’s most important critical supporter—introduced Pollock and Krasner to people like Newton, Klein, and Pearce. Though these practitioners aimed to heal their patients, sometimes, instead of cures for conditions like alcoholism, which they did not understand, they offered misguided therapy, coercive and destructive advice that ended up doing harm. It was Klein, after all, who postponed trying to stop Pollock from drinking and who encouraged his relationship with Kligman. When Judy Collins began therapy with Klein in 1963, she recalls, he told her that he had treated Jackson Pollock. He was angry that Pollock had killed himself in the accident, which he considered a suicide.108