EIGHTEEN

Retrospective, 1980–84

Bernard Gotfryd’s photograph of Lee Krasner, December 1983. Krasner got up out of her sickbed to pose in her bathrobe in her New York City apartment. She is standing in front of her 1983 Untitled collage on canvas (CR 599), the last work she completed. She held it back from her retrospective, saying: “I wanted to keep the one I just finished because I need to have my work to look at. Even when I’m just looking, I am working.”

ON MARCH 27, 1980, THE STONY BROOK FOUNDATION RECOGNIZED Lee Krasner’s lifelong “dedication to the arts” by giving her one of its Awards for Distinguished Contributions to Higher Education. Her fellow recipients were Sir Rudolf Bing, the Austrian-born opera impresario who served as the general manager of the Metropolitan Opera in New York from 1950 to 1972; and John Houseman, the noted actor and producer of both theater and film. The citation read in part: “Scores of prominent lay artists have learned from you. The critics here finally caught up to you. And now, Lee Krasner, the painter, is established as a prestigious and original artist in her own right as well as the strong and dedicated executor of the estate of the late, great Jackson Pollock…. All of this achievement called for a single-minded devotion to art.”1

Earlier that year Bill Rubin had written to Harry Rand about the Krasner retrospective, telling him how excited he was about it and saying he was sure it would be “very beautiful.”2 On May 20, Rand replied, confirming the plans for the Krasner retrospective to open in Washington before going on tour to the MoMA at a time that would fit into the museum’s schedule. Rand said that Joshua Taylor, the director of his museum, would write the catalogue’s preface and that he and Rubin would contribute short essays. Ellen Landau would write a “biography.” The substantial criticism would come from Barbara Rose.3 Rubin replied, telling him that he had long been “a great admirer” of Krasner’s work and that he looked forward to participating in the retrospective.4

In the summer of 1980, Krasner showed some of her work on paper from 1962 to 1970 at the Tower Gallery in Southampton, New York. Evelyn Bennett, writing for the Southampton Press, reported that Willem de Kooning was also supposed to show but pulled out at the last moment “by doubling the prices of his work (thereby making it impossible for the gallery to insure his paintings).” Krasner thought de Kooning was unprofessional. “You don’t pull out of a show at the last minute, and leave the gallery high and dry.”5 It’s possible that her resentment stemmed from regret at missing the chance to have her work compared to Pollock’s most significant rival instead of being compared to Pollock, as usual.

On view at the Tower Gallery were pieces from Krasner’s Water series: “This was a series using Douglass Howell [handmade] papers. It took courage to take gouache and bathe it. They were experiments in color, and a tough paper was needed for what I wanted to try. The monotone is something I tend to do a lot. With the water dipping techniques, I could get great varieties—and effects that would hold my interest and that of an observer too. You might say I was pushing, with the fixed points just the gouache and the paper.”6 She also said she had tried acrylics (first commercially available in the 1950s) and had not liked them at all.

Krasner explained to Bennett that an underlying philosophy of her work for the series related to the totality of life—what she considered “nature.”

“There are ‘elements of nature’ in my work,” she said, “but not in the sense of birds and trees and water. When I say nature I might mean energy, motion, everything that’s happening in and around me. That’s what I mean by nature.”

“So you’re really talking about everything living, really?” Bennett rejoined.

“Yes and death too,” Krasner replied, “things that are dead; everything.”

When told, “There’s something very religious about that,” Krasner returned, “Of course—art is religious; it has to be. That’s what I think, anyway. These people who do paintings of trivia—it’s a waste of my time.”7 What she meant by paintings of trivia was subject matter found in Pop Art such as soup cans, comics, and other such themes taken from popular culture.

Despite favorable press attention, Krasner still longed for a retrospective of her work in America and remained anxious about her reputation and her legacy. But a September 10, 1980, letter from Landau to Rubin indicated that the Washington part of the retrospective was set.8

Krasner met with Landau, still a graduate student when she traveled to New York. She took Krasner to lunch and began to go over a list of questions pertaining to her dissertation. Something rubbed Krasner the wrong way; for, according to Landau, Krasner started to scream at her and two days later telephoned to inform Landau that she was no longer involved with her retrospective. Krasner had decided to cut off Landau and would now entrust her legacy to Barbara Rose, in whom she had much more confidence, based on their years of friendship and Rose’s constant advocacy on her behalf.

Rose had been talking with Krasner for years about organizing her first American retrospective and now she was in a position to make it happen. Though Rose did not officially become the chief curator of the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston until March 1981, she had already been offered the position by the time that Krasner decided to ditch Landau. Krasner knew Rose’s writing and her high profile in the art world as well as her record organizing major shows for the Museum of Modern Art—one on Claes Oldenburg in 1969 and another on Patrick Henry Bruce in 1979. Over the years, Rose had spoken with Rubin about organizing a retrospective for Krasner and knew he respected her work.9

On February 19, 1981, just a week before Rose began her new job, Landau wrote to Krasner. She was about to receive her doctorate that June. In her letter, she apologized for the anger she had expressed in their last telephone conversation. Yet there was also a certain bitterness to the letter. She had been annoyed that Krasner seemed to question her expertise, especially after Landau had devoted three years to researching Krasner’s work for her dissertation. She felt she knew much more about Krasner’s early work than just about any other person. Landau wrote that she hoped Krasner would cease “holding up Gail Levin to me.” Landau was responding in part to Krasner’s earlier suggestion that she should consider making me the second reader of her dissertation.10 Landau claimed that my work on Krasner was insignificant. In turn, Krasner sent a copy of Landau’s letter to me on March 15. She enclosed her own letter telling me, “I’d like your reaction to the enclosed letter from Ellen Landau. I find it so arrogant, hostile and disgusting. Please read it and send your response to me.”11 I chose to stay out of their conflict and did not reply.

In the same letter, Landau also expressed resentment that Krasner preferred Barbara Rose as the curator of her retrospective, objecting that she should have made that preference clear at their first meeting. Landau also protested that Krasner had used her as a “pawn” to obtain the retrospective in New York. Rand claims to have suggested the retrospective to Krasner at the opening of the Pollock show at NCFA, but Landau says she was the one who first proposed Krasner’s retrospective to the Washington museum.12

What Landau failed to realize was how much Krasner had riding on the first American retrospective of her work. Except for the 1965 London show, this would be her only retrospective in her lifetime. Krasner knew Landau had not spent much time looking at her paintings because (as Landau stated in her letter) she had permitted Landau to look at the ones in storage only once. Gene Thaw, who believes Krasner was a smart woman when it came to analyzing people, recalled that Krasner feared that Landau was really only interested in Pollock.13 Rose shared this same concern with Krasner.14 In fact Landau’s dissertation covered Krasner’s career only up through 1949, and she often compared Krasner’s early work to that of Pollock, even before the two artists met. Krasner saw Landau as lacking both curatorial experience and the familiarity with her later work necessary to organize her retrospective. These perceived faults quickly turned into distrust.

The questions Landau posed to Krasner that day at lunch may have provoked some kind of alarm. Landau may have been diligent and capable, but to Krasner she was an untested student. Their dispute reflects the reciprocal insecurity of a woman artist who felt unjustly overlooked and an art historian who felt inadequately appreciated.

Krasner wrote to Professor William I. Homer, Landau’s faculty adviser at the University of Delaware, telling him how she had trusted Landau and had given her “free access” to her files of unpublished material for her dissertation research. Now, to Krasner’s consternation, she complained that Landau refused “to allow me to check her use of this material.” Then in a state of panic over what she termed a “very distressing problem,” she insisted, “She does not have my permission to publish any of the unpublished material without my checking and approving it.”15 Because Krasner had carefully saved many documents about her career with an eye to posterity, it is difficult to know what inaccuracies she feared, but it is clear that she was not about to leave the matter to chance.

Landau says that during this period, she attempted to call Krasner, but Krasner refused to speak with her. Landau also attempted to resolve the complaint to her faculty adviser by offering to show her dissertation to Krasner just before it was published.

Krasner’s frantic letter to Homer was dated the day before “Lee Krasner/Solstice” opened at Pace Gallery in March 1981. The exhibition was a show of her new collages, produced from rejected lithographs and paintings. The reviews were positive and noted that “Krasner has been painting for over a half-century now.”16

Barbara Cavaliere saw that the “internal movements in Krasner’s art signify the correspondences which link the present with the past and future,” singling out Vernal Yellow (1980) for its “vibrating movement.”17 In the New York Times, John Russell called the show “a heady mixture,” noting “the recurrent and unmistakable rhythm of her images.”18

Krasner, dressed in a perky felt hat and colorful scarf, was in an upbeat mood when she dropped in at the gallery for an interview with Jerry Tallmer, a critic at the New York Post: “Looks pretty good…. If you want my reaction to it, not bad at all.”19

There was a big difference between her collages of 1977 and those showing in the Pace Gallery. While the 1977 collages utilized her old charcoal drawings from classes with Hofmann, these were filled with what Tallmer termed a “new flaming burst of color.”

About the show, she said: “The last time I did high-key color was nineteen seventy-something. So I must go into that from time to time. This time, because of the color, I wanted to call this series The Rites of Spring. Stravinsky, you know…. But then I thought, well, that’s a little heavy, let’s just call it Solstice. Which was also keeping with my picture The Seasons.”

She had exhibited this piece the previous month in a show titled “Abstract Expressionists and Their Precursors” at the Nassau County Museum. Though she painted The Seasons from 1957 to 1958, it still interested her.

In his article Tallmer said he told Krasner, “You know…when the record of this era is written 50 years from now, you’re going to stand pretty high in it.”

“‘You think so?’ She held up two crossed fingers. ‘Maybe. I have to say that when I saw my work beside all those others at Gail Levin’s 1978 Whitney show [“Abstract Expressionism: The Formative Years”] I was flabbergasted.’”

“So were a lot of other people. Knocked out,” Tallmer responded.

She reflected, “Yeah, but I’m the artist. In a way there’s been this slow recognition of me. At one point I resented it. But now, in hindsight, it was a protection, a coating. I had to go into my studio and keep myself painting my own pictures, because the outside world wasn’t dealing with it anyway.”

Tallmer reported that “Krasner from Brooklyn crossed herself in the air” before she added, “My concern has been to align myself with my contemporaries and to stay alive. As a painter, I don’t mean just physically, but to have this work stay alive.”

That same spring John Post Lee, an art history major at Vassar College in his junior year, heard from a friend that Krasner was looking for someone to work for her during the summer. He didn’t want to return home to Philadelphia, so he set about making a quick study of Krasner and her work, memorizing the names and dates of many of her paintings. He met with her in her New York apartment and was able to identify Kufic (1966) as the painting hanging on the wall. The job was his.

That day Krasner told him to “stick around. Tom Armstrong, the director of the Whitney, is coming over to ask for a loan of a Pollock.”

The young man from Vassar watched the bow-tied director try to charm Krasner. But when Armstrong bent over to pull the Pollock catalogue raisonné off the shelf, “Krasner made a grotesque body motion toward him that he could not see, making clear that she just didn’t like Tom Armstrong.”20 What the student did not realize was Krasner’s long disdain for the Whitney for defining itself as a museum of “American art,” which she felt embraced nationalism. There were also rumors of Armstrong’s anti-Semitism (though denied by his supporters), which would also have put her off.21 It is not clear if it was because she had qualms about Armstrong, but Krasner only donated one minor ink drawing by Pollock to the Whitney, presumably in appreciation of her “Large Paintings” show. However, she donated many works by Pollock to both the Metropolitan and the Museum of Modern Art.

Krasner paid John Post Lee fifty dollars a week, plus room and board, with no days off. He served as her driver in his own car, for which she paid for the gas. He recalled her “Gestalt as very Depression-oriented.”22 She had no idea how much a young man could eat, so he would often sneak over to the neighborhood pizzeria. He would mix her favorite drink, a “sunrise,” consisting of cranberry and grapefruit juices with a splash of vodka and Campari. He discovered that when she drank, she became less guarded in her conversation.

John Post Lee thought Krasner was “very generous” and recalled that they talked “about everything.” Her politics were clearly liberal. Krasner often had him read aloud to her in the sitting room. Often this meant the newspaper. She expressed extreme irritation at President Reagan’s firing of the air traffic controllers.23 He also thought she was very intelligent and also “street smart.” He accompanied her everywhere that summer—to Terence Netter’s show at Stony Brook, to the homes of Ibram and Ernestine Lassaw, Jimmy and Dallas Ernst, James and Charlotte Brooks, Josephine and John Little, Patsy Southgate, and Edward Albee. He met her nephews Jason McCoy and Ronald Stein. Stein was then living next door and working as a pilot, flying out of East Hampton airport. As John worked with Krasner, he began to notice that she was quite infirm, already suffering from rheumatoid arthritis.

John Post Lee was with Krasner in August 1981, when the show “Krasner/Pollock: A Working Relationship,” organized by Barbara Rose, opened at Guild Hall. That fall the show traveled to the Grey Art Gallery at New York University. Interviewed about the prospect of seeing her work next to Pollock’s chronologically, Krasner responded gruffly: “It could be a terrible pitfall for me as an artist. I’m aware of that. I’ve been around. But I couldn’t give two hoots about that. I want to see it with my eye for myself—because I’ve never seen it visually, and until I see it visually, I don’t know what they’re talking about. And because I have an endless curiosity above and beyond the mob, I couldn’t care less about what their reaction is.”24 Krasner was upset that those male colleagues who had been influenced by Pollock were never compared directly to Pollock.

“Look,” Krasner said. “They don’t take de Kooning and put him up that way. And if de Kooning or Motherwell takes from Pollock, nobody even breathes a word about it. But with Lee Krasner, wow. It’s been a heavy, heavy number. It’s hard for them to separate me from Pollock in that sense.”25

Despite Krasner’s frustrations, at least one reviewer at Guild Hall understood her plight—the artist William Pellicone sought to reverse the common conception of Krasner’s position being beneath Pollock’s in the pantheon of great artists. “Krasner is identified as Jackson Pollock’s widow, an artist in her [own] right. It should read: Jackson Pollock, husband of Lee Krasner…. The revelation exposed is the fact that Lee Krasner gave Pollock everything because of her superior talent and he eventually destroys her true path with his superior barbaric, macho strength…. The Guild Hall show calls for a completely new evaluation of the Krasner-Pollock link.”26

Krasner was clear about dealing with Pollock’s reputation so many years after his death: “I may have resented being in the shadow of Jackson Pollock, but the resentment was never so sharp a thing to deal with that it interfered with my work.”27 On the other hand, Krasner admitted, “I stepped on a lot of toes because you know Pollock remains the magic name, and they had to deal with me to get to his works and I can say no very harshly. As a result, people in the art world acted out against me as a painter.”28

When a journalist described Krasner as “slowed a bit by arthritis, still actively painting” at the age of seventy-three, she was clear about her decision to devote so much energy to Pollock and stated emphatically: “I don’t feel I sacrificed myself And if I had it to do all over again from the very beginning, I’d do the same thing.”29

Barbara Rose maintained that had Krasner and Pollock lived during the days of feminism, Krasner might not have “played so wifely a role with Pollock” and might have even “dumped the genius.” Interestingly Krasner disagreed with Rose’s speculation. “I think I would do the same, identical thing all over again in the presence of talent like that, but it takes that kind of talent to move me. Anything else is for the birds.”30

Nevertheless, in the show’s catalogue, Rose argued that “of the many things Krasner and Pollock did for each other as artists, including criticize and support each other’s works, the greatest thing they did was to free each other from the dogma of their respective teachers.”31 Rose also asserted, “Jackson helped her to be free and spontaneous, and she helped him to be organized and refined.”32

Krasner seemed to appreciate Rose’s thoughtful advocacy.

John Post Lee read Rose’s manuscript aloud to Krasner sentence by sentence. He recalled that she would occasionally say, “That’s not true.” He also remembered that she paid particular attention to the mention of Pollock’s drinking, giving it emphasis.33 At another point, Krasner objected: “How come I’m the only one that is held accountable for being influenced by Pollock? Robert Motherwell pretends that he splatters paint because he was looking at a wave splashing on the beach. Oh, come on.”34 She also expressed disdain for de Kooning: “He’s interested in two things—women and real estate, so he buys a house and puts a woman in it.”35

Impressed by Krasner’s strong beliefs and good sense of humor, John Post Lee returned to Vassar at the end of the summer and wrote his senior thesis on Krasner’s collages, Eleven Ways to Use the Words to See.36

Among Krasner’s friends that she saw frequently in this period were the playwright Edward Albee, Sanford Friedman, and Richard Howard. Albee, who got along well with Krasner, surmised that, like her gay male friends, she considered herself “an outsider.” “She had a good anger. I admired it. She was a survivor.”37 He also admired her honesty but was puzzled at her dislike of Louise Nevelson, a close friend of his. Because both women came from poor Jewish immigrant families and had to struggle as women artists, Albee believed they were fighting similar battles. It’s more likely that Krasner was not thrilled to play the number two spot in the heart of Arnold Glimcher, their shared art dealer, who built his career promoting Nevelson’s work.

In late 1981, Krasner left Glimcher’s Pace Gallery, where she had been since 1977. The departure from Pace was described as “amicable” by both sides. Krasner commented, “We never had a fight. We are still friends. But I remember the dealer Pierre Matisse saying, ‘It’s the artists who’ve made my gallery.’ Arne, on the other hand, feels his gallery made his artists, and this is a serious disturbance. I wasn’t comfortable there.”38

On the other side, Glimcher maintained, “She wants a closer connection with her dealer, and I think she has made the right decision, although she certainly had the greatest success of her life in my gallery. I think she’s a wonderful artist, and I wish her the best.”39

In August 1981, a journalist reported that Krasner’s works commanded “as much as $30,000 and are in the collections” of major museums, including the Guggenheim Museum, the National Gallery, London’s Tate Gallery, and the Cologne Museum. If the journalist’s statements are true, then a sale to the Tate Gallery must already have been in the works when Krasner left Pace.40 In fact the Tate’s purchase of Krasner’s Gothic Landscape of 1961 was not announced in the press until March 1982. At that time, Tim Hilton, in the Observer in London, identified Krasner as “Jackson Pollock’s widow, long overshadowed and now in the odd position of being famous for being neglected,” while praising the new acquisition as “a marvelous picture.” He insisted, “This is better painting than the Gottliebs that hang next to it. I dare say that it’s better painting than the new Barnett Newman.”41 These words must have been music to Krasner’s ears. Glimcher sent her the clipping, which he inscribed, “Dear Lee—Thought that you’d like to have this—Arne.” Given Glimcher’s successes in placing Krasner’s pictures, it’s very possible that the unspoken point of difference between the dealer and the artist might have revolved around his desire to gain access to the estate of Jackson Pollock, which Krasner continued to hold close.

From the Pace Gallery, Krasner moved to the Robert Miller Gallery, then founded five years earlier. She was fond of Miller and his wife, Betsy, with whom Lee shared a birthday. Before they married in 1964, the Millers had both studied art at Rutgers, where they met Krasner’s nephew Ronald Stein, then teaching there. He had introduced them to Krasner and, as a result, Bob had become her studio assistant in 1963.42 Soon he moved on to work for the New York dealer André Emmerich during the same period that Pollock’s nephew Jason McCoy also worked there. Krasner’s long and affectionate association with Miller helps to explain her departure from Pace.

Nathan Kernan, who was then a young man working at the Robert Miller Gallery, recalls that he and his colleague John Cheim “loved especially the rather terrifying way she once said, in speaking of her annoyance with her former dealer, ‘I made it cry-stal clear to him…!’ She always pronounced the word collage with the accent on the first syllable, ‘COLL-age’ and ‘retrospective’ became, with perhaps an undertone of irony, ‘The RET-ro-spect.’” Kernan remembers that when they called Krasner from the gallery, “she would answer the phone suspiciously, ‘What’s up?’ immediately on alert for a problem and ready to pounce on any ambiguity or inanity we might have the misfortune to utter. We lived in terror of having something made ‘crystal clear’ to us.”43

Her first show there took place in October 1982 and was called “Lee Krasner: Paintings from the Late Fifties.” Grace Glueck described her work on view as “high-key abstractions that derive from figuration,” which “reinforces our astonishment that recognition was so late in coming to an artist of such gifts.”44

For Krasner’s efforts on behalf of Pollock’s art, she was named Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres by the French government. Jack Lang, the French minister of culture, presented the award to her on January 11, 1982, just before the opening of a major Pollock retrospective at the Musée national d’art moderne at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris. Krasner had made the show possible with her loans to the museum. She enjoyed receiving the award and getting attention at the opening, but she fell and injured her arm. The accident prevented her from making a planned visit to the caves of Lascaux.45 She had long been interested in prehistoric art, so it was quite a disappointment to forgo the visit. Krasner returned alone to New York, traveling on RMS Queen Elizabeth 2 (known as the QE2) from Southampton.

After Krasner’s return, the photographer Ann Chwatsky got an assignment to photograph her as one of five Hamptons artists for Long Island Magazine. She arranged for the shoot to take place in midmorning at Krasner’s apartment on East Seventy-ninth Street. When she arrived, Krasner was dressed in a “navy house smock,” looking “like the wrath of God.” When Chwatsky told Krasner that she wanted her to look as strong as her paintings, Krasner, who was then suffering from her arthritis, commented how hard it was for her to get ready without any help. Chwatsky had brought along makeup, which she applied, and a long magenta shawl, which she draped around the ailing artist for the shoot. The result was pleasing to both the photographer and her subject.

For several of Chwatsky’s shots, she posed Krasner in front of her latest painting, which she had made for “Poets and Artists,” an invitational show of forty-two artist-poet collaborations scheduled for Guild Hall that July. Although some of the artists and poets were paired by the show’s organizers, Krasner had teamed up with poet Howard Moss, whom she knew well through their mutual friend, Edward Albee.46 The idea for the show had come from the painter Jimmy Ernst, Krasner’s friend since the days when he worked for Peggy Guggenheim at Art of This Century. Taking the title of Moss’s poem “Morning Glory” as the title of her painting, Krasner inscribed in the upper-left-hand corner of her abstract canvas “How blue is blue,” the opening words of the poem.

That same summer Krasner called Chwatsky and invited her for lunch in the Springs house. Chwatsky sensed Krasner’s loneliness and invited her to go to a movie. They saw Diner, a 1982 film about the 1960s that Krasner loved. While they stood in line, many people recognized Krasner. Chwatsky observed that Krasner, who seemed aged and tired, was cranky as a result of dealing with her illness but extremely nice. Krasner spoke not about Pollock but of her concerns about conserving his paintings.47

Krasner’s nephew Ronald Stein was dismayed by her choices of medical treatment: “Lee was not into medical doctors…. If she had been properly dealt with medically, she wouldn’t later have refused to take cortisone for her arthritis because it might be bad for her health; yet here was a woman dying because she couldn’t move. And her colitis—that’s in the family and probably psychosomatic, only they would go to doctors who prescribe corrective medication and it would disappear. But Lee? She would go to witch doctors.”48

Krasner definitely preferred alternative medicine. Her last assistant, Darby Cardonsky, remembers that she went for acupuncture treatments.49 I recall that she wore copper bracelets, which she said were supposed “to help her arthritis.” Wearing copper for arthritis pain relief is an old folk remedy, based on the belief that copper is absorbed by the skin to relieve joint pain. The idea remains controversial. Out of desperation to find cures, Krasner had long turned to ideas from alternative and folk medicine, including some that were definite dead ends.

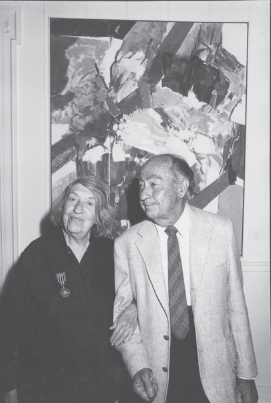

In August a frail Krasner joined John Little at Guild Hall, which held a retrospective of his work. Krasner held on to his arm as they posed for a photograph before one of his colorful abstract canvases—two old friends who once danced together to boogie-woogie music in the days when they met Mondrian more than forty years earlier.50

Almost a year later, in June 1983, Krasner received a letter from Steven W. Naifeh requesting an interview for a book he said he was writing on the history of the art world from the 1940s to the 1960s.51 This book was eventually published as a biography of Jackson Pollock, coauthored by Naifeh and Gregory White Smith. Krasner’s assistant, Darby Cardonsky, replied to the letter in June, suggesting that Naifeh contact her after the first of July, when Krasner expected to be in East Hampton. A bit earlier Krasner made appointments to be interviewed by Deborah Solomon, the author of a biography of Pollock, which appeared two years earlier than Naifeh and Smith’s, but she canceled them, the last time for February 28, 1984.52 Krasner was still bristling over Friedman’s biography of Pollock and was wary of biographers and, indeed, of all who wrote about her and Pollock, especially people she did not know well. Barbara Rose and Gene Thaw both recall how Krasner was at this time completely focused on her first American retrospective, even while daunted by her failing health.53

“During Lee’s last summer,” Carol Braider recounted, “when I was sort of her sitter, she was consumed by rage. She was afraid that if she couldn’t find a way to take out her hate on the world, she wouldn’t be able to go on painting or even exist. Those weeks were a nightmare. It was as if rage were all she had. Of a Bill de Kooning work going for $2 million, Lee said, ‘If Bill thinks that’s something, wait until he hears the latest in Jackson’s sales.’”54

Krasner was preoccupied with Barbara Rose’s text in the catalogue for the retrospective. The show was to open at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston on October 27, 1983, Krasner’s seventy-fifth birthday. Krasner enlisted Terry Netter to come out and help her edit it. He spent a week in the Springs house reading every word aloud to her. She would stop him and call Rose to ask for changes, which she could trust that Rose would make. Netter remarked, “Lee loved to think. She liked intellectuals. She was very bright. I don’t think that she read very much.”55 He suspected she was dyslexic.

As the opening neared, the press’s interest grew. Krasner told Michael Kernan at the Washington Post that she wished that museums would give artists retrospectives “every ten years or so, for the artists’ sake, so they can see the cycle of their own work…. Really, it shouldn’t be a once-in-a-lifetime thing.”56 Still, she said she would miss having her paintings around—“It’ll be two years before I get them back.”57

Before the show opened, Krasner admitted that she hadn’t let Rose see all of her work. She had kept one finished painting that Rose would have wanted—just to hang it on her wall. “I wanted to keep the one I just finished because I need to have my work to look at. Even when I’m just looking; I am working.”58 This was probably her Untitled collage on canvas (dated 1984 in the catalogue raisonné, but actually finished in 1983) before which she would pose in December 1983 for a photograph by Bernard Gotfryd.59

Krasner flew to Houston accompanied by Bob Miller and John Cheim and Nathan Kernan, who worked for the gallery. She was now in a wheelchair and had to spend much of the time in her room at the Warwick Hotel across the street from the museum. Among the dignitaries there to greet her was her friend James Mollison, director of the Australian National Gallery, who became notorious in 1973 for paying $2 million for Jackson Pollock’s Blue Poles, setting a new record price not only for Pollock but also for American painting. The money went not to Krasner but to the New York businessman and art collector Ben Heller, who had paid only $32,000 in 1956, when he had purchased the large 1952 painting once sold by Sidney Janis for only $6,000.60 When Krasner had told Janis that Pollock’s work was underpriced, she was correct. Now she could take satisfaction in what she had achieved in creating an international market for Pollock’s art. In 1978, Mollison purchased for his museum Krasner’s Cool White, a major canvas from 1959, once owned by David Gibbs, and then he followed that by acquiring several of her works on paper.

The large installation in Houston featured 152 paintings and drawings, including a biographical section, “Lee Krasner: The Education of an American Artist,” emphasizing the artist’s thorough training in the use of line. The exhibition was reduced in size in the show’s subsequent venues at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the MoMA in New York.

Krasner was delighted by the Houston opening. “The show looks terrific! Of course, I didn’t exactly have a chance to take a leisurely look [during the opening]; people were wishing me happy birthday and talking to me, but I found it a bit overwhelming—overpowering.”61 Terry Netter recalls that Krasner entertained a few close friends in her hotel suite, among them “Buddha” Eames from Krasner’s time at the Hofmann School. Krasner returned to look at the show again without the crowds.

In Time, the critic Robert Hughes, who attended the opening of the show in Houston, wrote that Krasner was a major American artist and wondered aloud what kept her from earlier recognition. He provided his audience with an answer that also gave voice to some of Krasner’s frustrations: “Women artists through the ’40s and into the ’50s in New York City were the victims of a sort of cultural apartheid, and the ruling assumptions about the inherent weakness, derivativeness and silly femininity of women painters were almost unbelievably phallocentric…. Add this to Krasner’s prickly contempt for diplomacy with critics, and one can see why for most of her life her work was scanted as ‘minor,’ an appendage to Pollock’s.”62

Hughes thought that “her dislike of groups always stopped her from presenting herself as a ‘feminist’ artist. Hence by the ’70s there was no lack of denigrators on both sides of the sex war tacitly writing her off as an art widow first, a painter second.”63 Though a feminist artist such as Judy Chicago scorned Krasner as “male identified,” Krasner’s ambivalence about feminist art is much more complicated than just not liking groups.64 Yes, she may have identified herself in relation to males, but her devotion to a man like Pollock stemmed not from an aversion to feminist groups, but rather from her love and admiration for him. Her choices were also affected by the cultural matrix of her immigrant childhood. She saw how women were treated in the world, and risked her own future by hitching onto the coattails of a man whom she saw as a genius and whom she believed she could nurture to success.

Hughes praised Krasner’s artistic “formal instinct,” noting that “she wanted to combine Picassoan drawing, gestural and probing, with Matissean color…. Is there a less ‘feminine’ woman artist of her generation? Probably not. Even Krasner’s favorite pink, a domineering fuchsia that raps hotly on the eyeball at 50 paces, is aggressive, confrontational…her line evokes eros…. This is an intensely moving exhibition, and it will suggest to all but the most doctrinaire how many revisions of postwar American art history are still waiting to be made.”65

In reviewing the retrospective for Artweek, Susie Kalil repeated Rose’s argument and supported Hughes’s criticism: “Of all the abstract expressionists, only Krasner had contact with virtually every major force that shaped its evolution…. Why hasn’t Krasner been accorded her due as a painter? The inequity can be directly attributed to the sexist attitudes rampant among critics and artists alike during the 1940s and 1950s. Krasner matured in an artistic environment to which few women, if any, were admitted.”66

Los Angeles Times critic William Wilson, who had rejected the feminist art movement during the 1970s, wrote that Krasner “may not be quite the peer of the great Action Painting innovators Pollock and de Kooning, but she certainly can be thought of in the same breath with Hans Hofmann, Robert Motherwell, and Franz Kline. She is arguably a better painter than such lesser lights as Adolph Gottlieb or William Baziotes.”67 At the time he wrote, this was a radical statement.

In San Francisco, Thomas Albright, a local newspaper critic beloved in the Bay Area for his promotion of local artists, reviewed Krasner’s traveling retrospective. He accused Rose of writing the catalogue essay in a “relentlessly uncritical, Horatio Alger style that has become the norm for this generally lamentable literary genre.”68 He also questioned “whether this hard-won reputation is wholly justified by the work itself, or whether it is more a product of feminist advocacy and/or the insatiable craving of art historians for disinterring new ‘masters’ from the Potters’ Field of the past.”69

Other critics also took issue with Rose. A Houston-based husband-and-wife team of artists, Ed Hill and Suzanne Bloom, argued in Artforum: “We should make no mistake in our reading of this innocent art play: Rose was writing history here, or, rather, correcting it to her image. Krasner would appear to have been the beneficiary of Rose’s historicism, but in truth she may have been simply the occasion for it. As a curator Rose has no light touch. She overdraws her case.”70

In Art in America, Marcia Vetrocq made an argument similar to the one made by the Blooms. Vetrocq claimed that Rose was preoccupied “with most art historians’ omission of Krasner from the first generation of Abstract Expressionism…as it has come to be petrified in art historical accounts…. [Krasner] will probably never be judged an innovator of the magnitude to satisfy a [Irving] Sandler or a [Henry] Geldzahler.”71 Vetrocq was correct that Sandler’s mind was too closed to be able to see Krasner as one of the founding members of abstract expressionism, which would have forced him to revise his own narrative.72

Though Vetrocq praised Krasner’s work and acknowledged that it had been “so little shown or reproduced,” she also asserted, “Krasner need not be proved the first or the only or the earliest in anything for her work to reward our attention and assume a position of dignity and significance in the history of postwar art. She has earned it.”73

In her own defense, Krasner reiterated in 1984, “It’s quite clear that I didn’t fit in, although I never felt I didn’t. I was not accepted, let me put it that way…. With relation to the group, if you are going to call them a group, there was not room for a woman.”74

Krasner returned from Houston exhausted but elated at the acclaim. Though she had been in a wheelchair, she had nonetheless spent hours looking at her works on view.75 She was now crippled by rheumatoid arthritis—she could barely stand, and it was impossible for her to walk. She “took to bed” and was too weak to return to painting. Darby Cardonsky, her assistant, would read her reviews to her.

Krasner was also suffering discomfort from intestinal problems such as diverticulitis (weak spots in the colon wall) and what may have been the complications of Crohn’s disease.76 Krasner had no choice but to write to Henry Hopkins, the director of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, that “health concerns” would not allow her to make the trip to see her retrospective installed there.77

Edward Albee admired Lee’s strength and recalled that she was in so much pain from arthritis that she remained confined to New York City, where she was taking gold injections.78 They were supposed to relieve joint pain and stiffness, reduce swelling and bone damage, and lower the chance of joint deformity and disability. But the injections didn’t help Krasner.

Assigned by Newsweek to go and photograph Krasner at her New York apartment, Bernard Gotfryd arrived to find that the ailing artist had not even gotten out of bed yet. He offered to return another time, but, not wanting to postpone the shoot, she asked him to wait for her to get ready. She wanted to know whom else he had photographed and he replied, “The list is so long, I’ll be here forever.”

“Then you photographed a lot of painters?” Krasner wanted reassurance. “Georgia O’Keeffe, Salvador Dalí, Andy Warhol, Barnett Newman,” he replied. When she responded to Barnett Newman’s name, he told her a story of taking Newman’s photograph during the installation of his show at the Guggenheim in the spring of 1966. Naturally the installation took place on a day when the museum was closed to visitors. Newman had gone downstairs to use the men’s room and not returned, so after a while Gotfryd went in search of him, finding the artist locked in the restroom, banging on the door, trying to summon someone to rescue him. Newman screamed, “What do they want me to do, have a heart attack?” Gotfryd forced the door open, got Newman out, but the artist was “in a rage,” even as he posed for the rest of the photographs. Krasner loved hearing the story about her old friend, who, in fact, had died of a heart attack in 1970, and, even in her pain, she smiled for Gotfryd and posed in front of her 1983 collage.79

Krasner also received a positive review in Newsweek from Mark Stevens, a future biographer of Willem de Kooning, who asserted, “Krasner fully deserves to be counted as one of the handful of important abstract expressionists.”80 Gotfryd’s photograph accompanied the review.

Krasner finished this collage and reworked a painting on New Year’s Eve 1983, even though she was suffering unbearable pain.81 By March she had lost a lot of weight, and her health had deteriorated to the extent that she began going to New York Hospital for treatment.82 Deborah Solomon, then writing a biography of Pollock, spoke to her briefly by phone as Krasner lay in her hospital bed on March 20, 1984, but by then Krasner was in no condition to give an interview. She was far too weak and too thin. Barbara Rose believes that Krasner was in so much pain that she stopped eating.

Krasner nonetheless agreed to be present in order to accept an honorary doctor of fine arts degree from the State University of New York at Stony Brook on May 20, 1984. John H. Marburger, the university’s president, wrote to her: “I am sorry to hear from Terry Netter that your arthritis is giving you worse trouble.”

Unfortunately Krasner was too ill to attend the ceremony at Stony Brook. Special permission was obtained to award the degree to her in absentia. This was the only honorary degree she ever received. The distractions of her failing health and her retrospective meant she worked very little during the last year: “I’m just poking along these days. Not working at full intensity,” she told a visiting critic.83 She knew she would not be able to make it to the Springs studio that summer.

LEE KRASNER DIED UNEXPECTEDLY AT THE AGE OF SEVENTY-FIVE ON June 19, 1984, at New York Hospital in Manhattan. She had been taken there for a transfusion in an effort to stop her weight loss, which had reduced her to ninety-four pounds. She had not survived long enough to see her long-anticipated retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, though she was at least assured that it was taking place.

Krasner was survived by two of her sisters, Esther Gersing and Ruth Stein. Because she left no instructions, the law designated that Krasner’s next of kin was Ruth Stein. She arranged for a funeral that took place on June 25 in Sag Harbor, conducted by Rabbi David Greenberg. Afterward she was buried in Green River Cemetery in Springs, next to Jackson Pollock’s grave. Gene Thaw is sure Krasner would have abhorred the Orthodox Jewish rites.84

Patsy Southgate recalled, “When I saw her three weeks earlier she was still being wheeled to the park, but she was very weak—and very low. She gave me the feeling of wanting to go, so it’s good that she did. But she wouldn’t have thought the funeral was so great—you can’t get the art world to come to Sag Harbor on a Monday.”85

Among the others who did come were Krasner’s nephews Ronald Stein and Jason McCoy and his wife, Diana Burroughs, and Krasner’s niece Rusty Glickman Kanokogi. At the service, Gene and Clare Thaw sat together with Gerald Dickler, Krasner’s longtime attorney, of whom she was quite fond. Among her Long Island friends were Jim and Charlotte Brooks, Ibram and Ernestine Lassaw, John and Josephine Little, Alfonso Ossorio and Ted Dragon, Terence and Therese Netter, Jeffrey Potter, the artist Esteban Vicente and his wife, Harriet, and Enez Whipple, the director of Guild Hall.

Krasner’s obituary in the New York Times stated, “In the last decade, Miss Krasner has begun to get her due, in part because of the effects of the women’s movement.”86 Barbara Rose offered words, saying, “Like Mondrian, she was a beacon of integrity. She had an absolute inability to compromise with anything.”

In accordance with Jewish tradition, Krasner’s gravestone was unveiled a year after her death, on June 23, 1985. Krasner’s grave is marked by a small stone that sits in front of Pollock’s larger stone. Many have observed that the stone appears to be located at Jackson Pollock’s feet and that his much larger stone grave marker overshadows hers. Others, however, have insisted that the smaller gravestone was what Krasner wanted: a place by Pollock’s side, but not to overshadow the man who she believed was the greater artist.

Her friend Ted Dragon later opined that Ronald Stein was responsible for the awkward arrangement in the cemetery and that he did it because he was angry at his aunt’s will. Krasner left Stein only $20,000, while she left several other family members, including her niece Rusty Kanokogi and her nephews Jason McCoy and Seymour Glickman, twice that sum. She appears to have based her decision on what she thought each relative needed at the time she signed her will in January 1979. She reserved most of her $10 million estate to fund the Pollock-Krasner Foundation.87

By leaving most of her fortune to endow the Pollock-Krasner Foundation, whose mission was to support “needy and worthy” artists, Krasner embraced the Jewish concept of Tikuun Olam, going out to repair the world. Terry Netter also believed that Krasner’s decision was a part of “the Judaic tradition of anonymous philanthropy,” because people can’t thank you personally when you’re dead. She had not forgotten the many years when she struggled to survive and the many artists who had never found adequate support. Among the needy artists that she helped after she had money was Igor Pantuhoff, her first love, who had fallen on hard times. He had died in 1972.

Krasner had been concerned about what would happen to the treasured home and studio, where she and Pollock had made art history. For help, she had turned to Netter, who had been the founding director of the Fine Art Center at the State University of New York at Stony Brook since 1979. Because she left the bulk of her estate to support artists in need, Krasner’s will stated that her home should become a museum only if an appropriate institution could be found to run the Springs house.

Netter spoke with John Marburger, the university’s president and a distinguished scientist, who agreed to run the house as a museum and study center. The house is now open as a museum, the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center. It is designated by the secretary of the interior as a National Historic Landmark because it has exceptional value or quality in illustrating or interpreting the heritage of the United States. Visitors can tour the house and the studio in which both Pollock and Krasner worked.

In August 1982, Lee Krasner joined John Little at Guild Hall in East Hampton, which held a retrospective of his work, and they posed before one of his colorful abstract canvases. Krasner and Little were two old friends who once danced together to boogie-woogie music forty years earlier, in the days when they were acquainted with Piet Mondrian. Photograph by Rameshwar Das, courtesy of the East Hampton Star.

Bill Lieberman, a former curator at MoMA and then at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, said that Krasner “painted in the modern idiom when Jackson was still in the regional style…. She should be remembered for the strength of her decorative sense and as an excellent draftsman.”88 Krasner’s friend Eugene Thaw, who coauthored and helped to fund the definitive catalogue of Jackson Pollock’s art, commented, “We are coming to the end of an era and she was a significant part of it. But because she was a woman and because she was overshadowed by Pollock, her due was late in coming.”89

A memorial service, arranged by Bill Lieberman, was held in the Medieval Sculpture Court at the Metropolitan Museum of Art on September 17, 1984. Among those who spoke were writer Susan Sontag, the art critic Robert Hughes, Terence Netter, and Edward Albee. Albee remarked that Krasner always “demanded the quality she gave. She looked you straight in the eye, and you dared not flinch.”90 Sontag praised Krasner’s art and her “talent for friendship, her genuine vitality and openness to experience.”91

Netter read from a citation that accompanied an honorary doctor of arts degree that the State University at Stony Brook awarded Krasner the previous May, declaring that she was “among the most distinguished American artists of the century” and an “inspiration to aspiring women artists.”92