April is, by proclamation and curriculum now, the poet’s month. “April” (or “Aprill”) is the third word of one of the first great poems in the English language, The Canterbury Tales, and the first word in what does its best to feel like the last great English poem, The Waste Land. April—“spungy,” “proud-pied,” and “well-apparel’d” April—is also, along with its springtime neighbor May, the most-mentioned month in Shakespeare, and has given a poetic subject to Dickinson, Larkin, Plath, Glück, and countless others. Why? Do we like its promise of rebirth, its green and messy fecundity? Its hopefulness is easy to celebrate or, if you’re T. S. Eliot, cruelly undercut, rooting his lilacs in the wasteland of death.

Eliot wasn’t the only one a little tired of the ease of April’s imagery. In 1936 Tennessee Williams received a note from a poetic acquaintance, a high school student named Mary Louise Lange who had recently won “third honorable mention” in the junior division of a local contest. “Yes, I think April is a fine month to write poetry,” she mused. “All the little spear-points of green pricking up, all the little beginnings of new poetic thoughts, all the shafts of thoughts that will grow to future loveliness.” A few days later, Williams, oppressed by the springtime St. Louis heat, despairing of his own youthful literary prospects, and perhaps distracted by all those “spear-points” and “shafts,” confessed to his diary that he was bored and lonely enough to consider calling on her: “Maybe I’ll visit that little girl poet but her latest letter sounded a little trite and affectatious—‘little spear points of green’—It might be impossible.”

In our man-made calendars, the yearly rebirth of Easter arrives most often in April, and novelists from Faulkner in A Fable to Richard Ford in The Sportswriter have been drawn to the structure and portent of Holy Week. Publishers annually bring us new spring books on religion and on the green pastimes of baseball and golf. But the April date most prominent in our lives now is associated more with death than birth: April 15, the American tax day since 1955. Lincoln, who died that day, had Whitman to mourn him, but Tax Day found few literary chroniclers until David Foster Wallace’s last, unfinished novel, The Pale King, which turns the traditional celebrations of the eternal seasons into the flat, mechanical repetition of modern bureaucratic boredom. In the IRS’s Peoria Regional Examination Center where Wallace’s characters toil, the year has no natural center, just a deadline imposed by federal fiat and a daily in-box of Sisyphean tasks, a calendar that in its very featureless tedium provides at least the opportunity to test the human capacity for endurance and even quiet heroism.

RECOMMENDED READING FOR APRIL

The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer (late 14th century)  When you feel the tender shoots and buds of April quickening again, set out in the company of Chaucer’s nine and twenty very worldly devouts, in what has always been the most bawdily approachable of English literature’s founding classics.

When you feel the tender shoots and buds of April quickening again, set out in the company of Chaucer’s nine and twenty very worldly devouts, in what has always been the most bawdily approachable of English literature’s founding classics.

The Confidence-Man by Herman Melville (1857)  It’s no coincidence that the steamboat in Melville’s great, late novel begins its journey down the Mississippi on April Fool’s Day: The Confidence-Man is the darkest vision of foolishness and imposture—and one of the funniest extended jokes—in American literature.

It’s no coincidence that the steamboat in Melville’s great, late novel begins its journey down the Mississippi on April Fool’s Day: The Confidence-Man is the darkest vision of foolishness and imposture—and one of the funniest extended jokes—in American literature.

“When Lilacs Last in the Door-yard Bloom’d” by Walt Whitman (1865) and The Waste Land by T. S. Eliot (1922)  Whitman’s elegy, composed soon after Lincoln’s murder, heaps bouquets onto his coffin, and a livelier and more joyful vision of death you’re not likely to find. You certainly won’t in The Waste Land, written after a war equally bloody and seemingly barren of everything but allusions (to Whitman’s funeral lilacs among many others).

Whitman’s elegy, composed soon after Lincoln’s murder, heaps bouquets onto his coffin, and a livelier and more joyful vision of death you’re not likely to find. You certainly won’t in The Waste Land, written after a war equally bloody and seemingly barren of everything but allusions (to Whitman’s funeral lilacs among many others).

The Sportswriter by Richard Ford (1986)  Beginning with a Good Friday reunion with his ex-wife on the anniversary of their son’s death, Ford’s indelible ex-sportswriter Frank Bascombe reckons with balancing the small, heart-lifting pleasures of everydayness with the possibilities of disappointment and tragedy that gape underneath them.

Beginning with a Good Friday reunion with his ex-wife on the anniversary of their son’s death, Ford’s indelible ex-sportswriter Frank Bascombe reckons with balancing the small, heart-lifting pleasures of everydayness with the possibilities of disappointment and tragedy that gape underneath them.

The Age of Grief by Jane Smiley (1987)  Smiley’s early novella is still her masterpiece, a story of a family swept through by flu and a young marriage struggling to survive the end of its springtime that’s as close to an American version of “The Dead” as anyone has written.

Smiley’s early novella is still her masterpiece, a story of a family swept through by flu and a young marriage struggling to survive the end of its springtime that’s as close to an American version of “The Dead” as anyone has written.

My Garden (Book): by Jamaica Kincaid (1999)  “How vexed I often am when I am in the garden, and how happy I am to be so vexed”: Midway through life, Kincaid started planting in her yard in most “ungardenlike” ways, and her garden book is willful and lovely, made of notes in which she cultivates her hatreds as passionately as her affections.

“How vexed I often am when I am in the garden, and how happy I am to be so vexed”: Midway through life, Kincaid started planting in her yard in most “ungardenlike” ways, and her garden book is willful and lovely, made of notes in which she cultivates her hatreds as passionately as her affections.

The Likeness by Tana French (2008)  Ireland’s French crafted an intrigue with equal elements of the Troubles and The Secret History in her second novel, in which Detective Cassie Maddox is seduced by the mid-April murder of a student who had been playing with an identity disturbingly close to her own.

Ireland’s French crafted an intrigue with equal elements of the Troubles and The Secret History in her second novel, in which Detective Cassie Maddox is seduced by the mid-April murder of a student who had been playing with an identity disturbingly close to her own.

The Pale King by David Foster Wallace (2011)  Don’t expect a novel when you open up The Pale King, culled from manuscripts Wallace left behind at his suicide. Read it as a series of experiments in growing human stories out of the dry soil of bureaucratic tedium, and marvel when real life, out of this wasteland, suddenly breaks through.

Don’t expect a novel when you open up The Pale King, culled from manuscripts Wallace left behind at his suicide. Read it as a series of experiments in growing human stories out of the dry soil of bureaucratic tedium, and marvel when real life, out of this wasteland, suddenly breaks through.

April 1

BORN: 1929 Milan Kundera (The Unbearable Lightness of Being), Brno, Czechoslovakia

1942 Samuel R. Delany (Dhalgren, Nova), New York City

DIED: 1950 F. O. Matthiessen (American Renaissance), 48, Boston

1966 Flann O’Brien (The Third Policeman, At Swim-Two-Birds), 54, Dublin

NO YEAR The most sustained April Fool’s joke in the history of American literature begins with the appearance in St. Louis of a mute stranger in a cream-colored suit stepping on board the steamboat Fidèle bound for New Orleans. Meet the title character of Herman Melville’s The Confidence-Man: His Masquerade, set on April Fool’s Day and published—by coincidence, apparently—on that day too in 1857. Its unrelenting skepticism was met with confusion and indifference, and the once-popular Melville didn’t publish another novel in the remaining thirty-four years of his life. It took another century before The Confidence-Man was rediscovered as one of his most radical and brilliant inventions.

1936 After serving seven and a half years for robbery, Chester Himes, his stories already published in Esquire, was released from the London Prison Farm in Ohio.

1956 On the morning of April Fool’s Day, Edward Abbey began his first workday as a national park ranger by stepping out of his government trailer and watching the sun rise over the canyonlands of Arches National Monument in Moab, Utah. Outfitted with trailer, truck, ranger shirt, tin badge, and five hundred gallons of water, Abbey was left more or less alone for six months, which he recorded in journals he typed up a decade later into the manuscript of Desert Solitaire, a cantankerous appreciation of the wild inhumanity of nature and a warning against the encroaching “Industrial Tourists” the park was already being prepared for.

1960 There was “something intensely surprising” about witnessing the birth of his daughter Frieda, Ted Hughes later wrote a friend, and “also something infinitely disastrous and shocking about it.”

1978 Haruki Murakami had worked day and night for four years at his small jazz club in Tokyo called the Peter Cat when, with an inexplicable and impulsive simplicity that seems right out of his fiction, he decided to try something new. He was drinking a beer in the grassy embankment beyond the outfield fence at a Yakult Swallows baseball game when Dave Hilton, a new American player on the Swallows, hit a double down the left-field line, right on the sweet spot of his bat, and Murakami thought, “You know what? I could try writing a novel.” He had no idea what the book would be about, but by the fall he finished Hear the Wind Sing. The next spring the novel won a magazine contest he forgot he’d entered, and his writing career began.

2010 Sebastian Junger, in the New York Times, on Karl Marlantes’s Matterhorn: “It’s not a book so much as a deployment, and you will not return unaltered.”

April 2

BORN: 1725 Giacomo Casanova (Story of My Life), Venice, Italy

1805 Hans Christian Andersen (“The Little Mermaid,” “The Red Shoes”), Odense, Denmark

DIED: 1966 C. S. Forester (Horatio Hornblower series, The African Queen), 66, Fullerton, Calif.

1796 Of the “authentic” documents from the life of William Shakespeare—original manuscripts of Lear and Hamlet, a love letter and poem to Anne Hathaway, an awkwardly scrawled note from Queen Elizabeth—that poured forth from a mysterious old chest William Henry Ireland claimed to have found, the most audacious forgery was Vortigern, an unknown play said to be in the Bard’s hand whose sole performance at Drury Lane on this evening quickly turned into farce. Even the play’s performers smelled a fraud by then, and when the star, John Kemble, repeated the line “And when this solemn mockery is ended,” with a leer at the audience, a bedlam of derision ensured the humiliation of Ireland, the play’s discoverer and its true author.

1894 In reply to a letter from his father, the Marquess of Queensberry, about his “loathsome and disgusting relationship” with Oscar Wilde, Lord Alfred Douglas wired back, “What a funny little man you are.”

1913 Kurt Wolff, Franz Kafka’s new publisher, wrote to the author, “Please be good enough to send me a copy or the manuscript of the bedbug story.”

1957 “I was overwhelmed to get the little book, filched from the library, and I hope I deserve it,” E. B. White wrote in thanks to his Cornell classmate H. A. Stevenson. “What a book, what a man!” The man was William Strunk Jr., and the book was The Elements of Style, a privately printed (and stapled) writing manual from 1918 known to Strunk’s Cornell students as “the little book.” In July White wrote an appreciation of the book and its bold strictures in The New Yorker and sent it to an editor at Macmillan to see if they might bring it back into print. Before long, “the little book,” with White’s edits and additions, was known instead, to a much wider audience, as “Strunk and White.”

1990 The remains of Jack Arthur Dodds, which fit tidily into a screw-top plastic jar the size of a pint glass, may not be as unwieldy as the coffin that carried the body of Addie Bundren in As I Lay Dying, and Graham Swift’s narrative pyrotechnics may be more modest than William Faulkner’s, but Last Orders, his quiet and generous story of four men fulfilling Jack’s final request by carrying his ashes to the sea, gathers a weight of its own while following a funereal path similar to the one Faulkner laid down. On their pilgrimage, which begins with pints and a shot in Bermondsey and ends in wind and rain on a pier in Margate, some secrets are revealed between these old friends, but far more stay buried where they have been for years, to be confessed only to us.

April 3

BORN: 1593 George Herbert (The Temple), Montgomery, Wales

1916 Herb Caen (San Francisco Chronicle columnist), Sacramento, Calif.

DIED: 1971 Manfred Lee (half of the Ellery Queen pseudonym), 66, Waterbury, Conn.

1991 Graham Greene (The End of the Affair), 86, Vevey, Switzerland

1878 Dining at Zola’s new house with Flaubert and Edmond de Goncourt, the novelist Alphonse Daudet compared the grouse to “an old courtesan’s flesh marinated in a bidet.”

1882 It was still the evening of the same day as the killing when Bob Ford, with eager and self-regarding confidence, took the stand at the inquest and testified that from six feet away that morning he had shot the outlaw Jesse James while he was unarmed and dusting a picture frame. He hadn’t confessed so freely, though, when he made his escape after the gunshot, according to Ron Hansen’s meticulously researched and imagined novel, The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford. “Bob, have you done this?” James’s freshly widowed wife wailed. “I swear to God that I didn’t,” he replied, and then ran to the telegraph office with his brother to wire the governor of Missouri, who had authorized a $10,000 reward for his death or capture, “I have killed Jesse James. Bob Ford.”

1920 Zelda Sayre, the daughter of Anthony Dickinson Sayre, justice of the Supreme Court of Alabama, and Minerva Machen Sayre, of Montgomery, Alabama, wed Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald, the son of Edward Fitzgerald, formerly of Procter & Gamble, and Mollie McQuillan Fitzgerald, of St. Paul, Minnesota, at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Manhattan. The bride was a graduate of Sidney Lanier High School; the groom was graduated from Princeton University and recently published his first novel, This Side of Paradise.

1952 Julia Child, the wife of an American diplomat in Paris, reading what she called an “able diatribe” by Bernard DeVoto in Harper’s on the poor quality of American kitchen knives, sent DeVoto a French paring knife in appreciation. In thanks, DeVoto’s wife, Avis, replied to Child on this day with a long, friendly letter on cutlery and cuisine, and so began a correspondence and collaboration that resulted in the publication nearly a decade later of the first volume of Child’s groundbreaking Mastering the Art of French Cooking. Meanwhile, As Always, Julia, the collection of letters between Child and DeVoto published in 2010, is itself a minor classic of food writing and friendship.

April 4

BORN: 1914 Marguerite Duras (The Lover, The Ravishing of Lol Stein), Saigon

1928 Maya Angelou (I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings), St. Louis

DIED: 1991 Max Frisch (I’m Not Stiller, Homo Faber), 79, Zurich, Switzerland

2013 Roger Ebert (The Great Movies, Life Itself), 70, Chicago

1846 Gustave Flaubert sat with the body of his deceased friend Alfred Le Poittevin for two days and two nights and then wrapped him in shrouds and placed him in his coffin for burial.

1886 A close friendship begun over thirty years before, when Émile Zola, age fourteen, met a “large, ungainly boy” named Paul Cézanne in boarding school in Aix-en-Provence, ended with a chilly note on this day from the painter to the novelist that began, “I have just received L’Oeuvre, which you arranged to send me.” L’Oeuvre, Zola’s fictional portrait of a novelist’s relationship with a painter resembling Cézanne and his fellow Impressionists who descends into madness and failure, drew the ire of Monet, Renoir, and Pissarro, while Cézanne, who had long chafed under Zola’s more rapid success, said nothing more to his old friend about the book. In fact, the two of them never spoke to nor saw each other again.

1924 No one was entirely happy when Mabel Dodge Luhan, whose bohemian magnetism drew D. H. and Frieda Lawrence—among many other writers and artists—to Taos, New Mexico, took a run-down ranch she had given her son and bestowed it on Frieda instead. The Lawrences did enjoy being homeowners for the first time in their restless lives but felt beholden to Luhan, so in exchange they gave her the manuscript of Sons and Lovers, which Luhan took as an offense to her generosity and which the Lawrences later discovered, to their dismay, was worth far more than the ranch. D. H. Lawrence’s tuberculosis prevented him from staying there long, but after his death in 1930 Frieda made the ranch her permanent home.

1925 Carl Sandburg telegraphed news of his Lincoln biography to his wife, Paula, “Harcourt wires book serial rights sold to Pictorial Review for $20,000. Fix the flivver and buy a wild Easter hat.”

1968 Many stories move with a weary fate toward the assassination of Martin Luther King. Charles Johnson’s Dreamer, the imagined story of a man hired to double for King, nears its close on the balcony of Memphis’s Lorraine Motel, as does Taylor Branch’s three-volume history, America in the King Years, which devotes seven of its nearly 3,000 pages to the hours between King’s last public words, “Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord,” and his final ones in private, “Ben, make sure you play ‘Precious Lord, Take My Hand,’ in the meeting tonight. Play it real pretty.” Meanwhile, George Pelecanos’s Hard Revolution, the most ambitious of his encyclopedic series of DC crime novels, builds toward the aftermath of the assassination, when violence swept through the nation’s capital along with the news.

April 5

BORN: 1588 Thomas Hobbes (Leviathan), Westport, England

1920 Arthur Hailey (Airport, Hotel, Wheels), Luton, England

DIED: 1997 Allen Ginsberg (Howl, Kaddish), 70, New York City

2005 Saul Bellow (Herzog, Humboldt’s Gift, Ravelstein), 89, Brookline, Mass.

1832 Despite his vow to quit gambling, William Makepeace Thackeray played cards until four in the morning, losing eight pounds, seven shillings.

1919 Katherine Mansfield wrote to Virginia Woolf that her cat, Charlie Chaplin, had given birth to kittens named Athenaeum and April.

1919 After a performance of his play Judith, Arnold Bennett lamented, “Terrible silly mishaps occurred with the sack containing Holofernes’s head in the third act, despite the most precise instructions to the crowd.”

1936 By the time of the elaborate Founder’s Day festivities at the Tuskegee Institute, three years after he arrived from Oklahoma City as an eager and optimistic music major, Ralph Ellison had soured on the college and turned his interests to literature, so he listened to the language of the featured speaker with a skeptical but attentive ear. The speaker was Dr. Emmett J. Scott, the longtime right-hand man of Tuskegee’s charismatic founder, Booker T. Washington, and his tribute to Washington that day planted the seeds of the oration of Rev. Homer A. Barbee—“Thus, my young friends, does the light of the Founder still burn”—in Invisible Man, the novel that made Ellison one of Tuskegee’s best-known alumni.

1952 “In lots of the books I read,” deputy sheriff Lou Ford opines, “the writer seems to go haywire every time he reaches a high point.” That won’t happen with his story, Ford promises us: “I’ll tell you everything.” And tell everything he does in The Killer Inside Me, the blackest of Jim Thompson’s string of sly and brutal noir novels from the ’50s and ’60s. Most obsessively of all, Ford confesses that on the 5th of April in 1952 he killed Amy Stanton, the woman who thought she was about to marry him. It’s neither the first nor the last death Ford orchestrates; the final one, in an explosion of shots and shouts, is his own.

1969 Lester Bangs was selling shoes in El Cajon, California, and taking classes at San Diego State when a cover profile of the MC5 in Rolling Stone led him to buy their debut, Kick Out the Jams. He thought the record was a derivative fraud, though, and wrote Rolling Stone to tell them so, adding that he could write as well as anyone they had. They agreed, at least enough to print his review in their April 5 issue, launching Bangs on a critical career that matched the live-fast, die-young arc of his rock heroes. Bangs’s reviews and manifestos, collected in Psychotic Reactions and Carburetor Dung, read like uninhibited mash notes from a love affair with rock ‘n’ roll: passionate, besotted, and angry; vigilant for signs of betrayal but animated at all times by the hope of transcendence.

April 6

BORN: 1866 Lincoln Steffens (The Shame of the City), San Francisco

1926 Gil Kane (Green Lantern, The Atom), Riga, Latvia

DIED: 1992 Isaac Asimov (I, Robot; Foundation), 72, New York City

2005 Frank Conroy (Stop-Time, Body and Soul), 69, Iowa City, Iowa

1862 The Battle of Shiloh at the end of the Civil War’s first year was the bloodiest by far in American history and marked a new stage in the war’s carnage that stunned the nation. Despite the Union’s ultimate victory after two days of fighting, blame was spread widely, and most of it settled on Lew Wallace, a major general at age thirty-four, whose “lost division” spent the battle’s first day marching back and forth behind the front lines following an ambiguous message from General Grant. Wallace was relieved of his command and for the next two decades protested his scapegoating, with satisfaction coming only when Grant acknowledged Wallace’s innocence in a reluctant footnote in his Memoirs and when Wallace’s fame for his bestselling 1880 novel, Ben-Hur, finally eclipsed his infamy at Shiloh.

1924 After finishing chapter eighteen of An American Tragedy, Theodore Dreiser had two hot dogs and a cup of coffee at a restaurant at Fourteenth Street and Seventh Avenue and then walked in the rain to Fifty-ninth Street, full of “many odd thoughts about the city.”

1934 M. F. K. Fisher, having “settled at a steady pace of about fifteen pages at a time,” read Ulysses on the beach at Laguna, occasionally turning herself “neatly to brown on both sides in the sun.” Later, she made a chocolate cake.

1987 For a few years in the mid-’80s, Jonathan Franzen found an ideal job for a frugal young writer: working weekends reading data at a Harvard seismic lab, which supported him and his wife while he wrote his first novel, The Twenty-Seventh City, the rest of the week. It also gave him a subject for his rich and undercelebrated second novel, Strong Motion, whose story hinges on clusters of small earthquakes in the Boston area that may or may not be caused by the pumping of industrial waste into deep underground wells. The first of the tremors, despite its mild 4.7 magnitude, claims on this day its only victim, the step-grandmother of his protagonist, Louis Holland, when it knocks her off a barstool.

April 7

BORN: 1770 William Wordsworth (The Prelude, “Tintern Abbey”), Cockermouth, England

1931 Donald Barthelme (Snow White; Come Back, Dr. Caligari), Philadelphia

DIED: 1836 William Godwin (Caleb Williams), 80, London

1977 Jim Thompson (The Killer Inside Me, Pop. 1280), 70, Los Angeles.

1874 “Look here—what day is Easter this year?” “Why, of course, the first week in April. Why?” “I’m going to be married in a month.” A half hour before, Newland Archer had been convincing the beautiful and worldly Countess Olenska to abandon their promises to others and be together when a telegram from his fiancée arrived: “Parents consent wedding Tuesday after Easter at twelve Grace Church eight bridesmaids please see Rector so happy love May.” In The Age of Innocence, Edith Wharton’s great novel of renunciation, Newland keeps his promise to May to marry, though he doesn’t forget the countess, who, after all, has just told him, “I can’t love you unless I give you up.”

1919 Though he started with high hopes on this day, working on commission as the advertising manager of the Little Review, Hart Crane managed to sell only two ads, for Mary Garden Chocolates and “Stanislaw Portapovitch—Maître de Danse” over the next several months before giving up.

1935 While John Dos Passos filmed the proceedings, Ernest Hemingway shot himself through both legs when a bullet ricocheted that was meant to kill a shark they had hooked onboard.

1962 The ideas suggested by Robert A. Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land took hold with surprising speed after it was published in 1961: “grok” soon entered the language, and some readers began to take its vision of religion, sex, and justice as gospel. On this day two college friends, Tim Zell and Lance Christie, having been “seized with an ecstatic sense of recognition” by the novel, performed a water-sharing ceremony modeled after the book and later formed the Church of All Worlds, which called science fiction the “new mythology of our age.” Heinlein kept a polite distance from such acolytes, and in 1972 responded to a letter from Zell by saying, “Anyone who takes that book as answers is cheating himself. It is an invitation to think—not to believe.”

1967 “I do not plan to be a 79-year-old lollipop, Mr. Rich,” fifty-eight-year-old M. F. K. Fisher wrote her sixty-three-year-old boyfriend, Arnold Gingrich, publisher of Esquire. “Even for you. If I should live that long, I’ll be a bag of bones, probably rather bent and even more probably racked with arthritic pains, irascible in a barely controlled manner, very impatient of human frailties and quirks, concentrated on my own determination to stay vertical and free. Not an exactly lovable picture!”

1967 The new film critic of the Chicago Sun-Times, Roger Ebert, debuted with a review of an “obscure French movie,” Galia: it opens with shots of the ocean, he noted, but “it’s pretty clear that what is washing ashore is the French New Wave.”

April 8

BORN: 1909 John Fante (Ask the Dust), Denver, Colo.

1955 Barbara Kingsolver (Animal Dreams, The Lacuna), Annapolis, Md.

DIED: 1958 George Jean Nathan (The Smart Set, The American Mercury), 76, New York City

1979 Breece D’J Pancake (The Stories of Breece D’J Pancake), 26, Charlottesville, Va.

1809 With remarkable but characteristic patience, it wasn’t until six years after her novel Susan was purchased by the publisher Richard Crosby that Jane Austen inquired about her manuscript. “I can only account for such an extraordinary circumstance,” she wrote, in a tone of passive indignation adopted by countless thwarted authors before and since, “by supposing the MS by some carelessness to have been lost.” Replying on this day, Crosby asserted that “there was not any time stipulated for its publication, neither are we bound to publish it,” and offered to sell it back to her for the £10 he had paid. Not for another seven years did Austen take him up on the offer, and not until after her death was the novel published, her brother having changed its title to the more distinctive Northanger Abbey.

1877 Henry James deplored the social desert of London during Easter week to his sister Alice: “ ‘Every one’ goes out of town . . . and a gloomy hush broods over the place.”

1928 “Never you mind,” Dilsey tells her daughter, who is ashamed of her mother’s open weeping as they walk from church on Easter Sunday. “I seed de beginnin, en now I sees de endin.” For “April 8, 1928,” the final section of The Sound and the Fury, William Faulkner stepped back from the voices of the three Compson brothers who had told the tale of their family’s decline to that point. He gave the story over to the voice of an outside narrator, and gave the center of it not to Caddy, the fourth Compson child, but to Dilsey, the black cook who has witnessed the Compsons’ rise and fall and who, as head of her own family, represents, perhaps, the rebirth promised by Easter.

1999 Lionel Shriver’s agent, after reading the manuscript of We Need to Talk About Kevin and deciding there was no way she could sell “a book about a kid doing such maxed-out, over-the-top, evil things, especially when it’s written from such an unsympathetic point of view,” suggested that Shriver only “allude to” the events of this day rather than describe them in the detail that she does near the book’s end. But Shriver didn’t cut the full description of Kevin Khatchadourian’s school massacre—ripped from the headlines at the time and reflected in them more than once since—and, though her book was rejected by dozens more agents and editors, it eventually found a sizable readership for its story of an incorrigibly sociopathic child and a mother haunted by the question of whether her son made her a bad mother, or her mothering made a bad son.

April 9

BORN: 1821 Charles Baudelaire (Les Fleurs du mal, Paris Spleen), Paris

1929 Paule Marshall (Brown Girl, Brownstones; Praisesong for the Widow), Brooklyn

DIED: 1553 François Rabelais (Gargantua and Pantagruel), c. 58, Paris

1997 Helene Hanff (84, Charing Cross Road), 80, New York City

1909 The day Robert Peary and Mathew Henson reach what they think is the North Pole in E. L. Doctorow’s Ragtime doesn’t match the historical record, which says it happened on April 6 (and which also says Henson’s name was “Matthew”), but then again, in Doctorow’s account Peary and Henson aren’t sure from their instrument readings whether they are even at the exact pole (and historians since have largely decided that they weren’t). Nevertheless, “Give three cheers, my boy,” Doctorow’s Peary tells Henson. “And let’s fly the flag.” Composed in a naive, declarative style and populated with a cast that mixes the historically iconic (Peary, Houdini, Emma Goldman) with the anonymously generic (Mother, Father, Mameh, Tateh), each so abstracted as to be both merely and vividly representative of their times, Ragtime embraces the mythmaking at the heart of the historical novel.

1932 Bruno Schulz, at a conference for teachers of handicrafts in Stryj, Poland, presented a lecture titled “Artistic Formation in Cardboard and Its Application in School.”

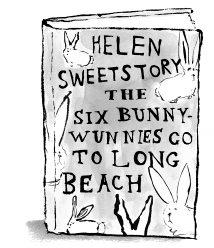

1971 It’s a one-sided love affair. On one side, Miss Helen Sweetstory, author of The Six Bunny-Wunnies and Their Pony Cart, The Six Bunny-Wunnies Go to Long Beach, and so on, and on the other, Snoopy, aspiring author of “It Was a Dark and Stormy Night” and Miss Sweetstory’s biggest fan, who decides on this day to write his beloved a fan letter. He sends mash notes and she replies with form letters, but he still believes that a) she loves him and b) she’s going to introduce him to her agent. After all, “famous authors like to receive manuscripts from unknown writers.” Only the discovery that Miss Sweetstory owns twenty-four cats is enough to break his fever. Enough, he tells Linus: “Back to Hermann Hesse.”

1986 May Sarton returned to her journal for the first time after a stroke at age seventy-three: “There in my bed alone the past rises like a tide, over and over, to swamp me with memories I cannot handle. I am as fragile and naked as a newborn babe.”

April 10

BORN: 1934 David Halberstam (The Best and the Brightest), New York City

1941 Paul Theroux (The Great Railway Bazaar), Medford, Mass.

DIED: 1955 Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (The Phenomenon of Man), 73, New York City

1966 Evelyn Waugh (Scoop, Brideshead Revisited), 62, Combe Florey, England

1881 Having chosen months of bed rest for a bladder infection instead of an operation so he could keep delivering his monthly installments of his new novel, A Laodician, to Harper’s magazine, Thomas Hardy set foot outside his house for the first time since October.

1903 Less than three months into a penniless Paris adventure at age twenty-one, during which his mother in Dublin pawned household goods to keep him from starving, James Joyce received a telegram reading, “Mother dying come home father.” (He did; she was.) Much later, that same message, included in Ulysses as a telegram received by Stephen Dedalus, would end up at the center of scholarly controversy, with some Joyceans arguing that the original typesetters had mistakenly corrected Joyce’s typically punning revision of his own life, and that the text should read, as it does now in some editions, “Nother dying come home father.”

1925 Despite his last-minute requests to change its “rather bad than good” title to “Trimalchio in West Egg,” “Gold-Hatted Gatsby,” or “Under the Red White and Blue,” F. Scott Fitzgerald’s third novel was published on this day by Scribner’s as The Great Gatsby. Ten days later his editor, Maxwell Perkins, cabled Fitzgerald in Paris, “Sales situation doubtful excellent reviews”; even some admiring reviewers, though, thought Gatsby, with its shiny surfaces, “trivial” story, and too-timely slang, would prove “a book of the season only.” The sales did allow Fitzgerald to pay off a substantial debt to his publisher, but they failed to reach the levels of his previous novels, and even at his death fifteen years later copies from the small second printing of Gatsby remained unsold.

1926 Perhaps only half in jest, H. L. Mencken suggested that losing presidential candidates should be executed and tossed into the Potomac.

1961 Susan Sontag attended a double feature of I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang and The Maltese Falcon at Manhattan’s New Yorker theater.

1967 In the “cold late spring of 1967,” Joan Didion took her notebook and her eye for entropy to meet some of the young people who were gathering in San Francisco, where she found, along with restless anarchists, trip-seeking teenagers, and a five-year-old sampling acid, a plaintive public notice beginning, “Last Easter Day / My Christopher Robin wandered away. / He called April 10th / But he hasn’t called since.” In her resulting dispatches, published in the Saturday Evening Post under the cover line “The Hippie Cult: Who They Are, What They Want, Why They Act That Way,” and later as the title essay in Slouching Toward Bethlehem, Didion diagnosed the end of the Summer of Love before it had even begun.

April 11

BORN: 1901 Glenway Wescott (The Pilgrim Hawk), Kewaskum, Wis.

1949 Dorothy Allison (Bastard Out of Carolina, Cavedweller), Greenville, S.C.

DIED: 1970 John O’Hara (Appointment in Samarra, BUtterfield 8), 65, Princeton, N.J.

1987 Primo Levi (The Periodic Table, The Drowned and the Saved), 67, Turin, Italy

1681 A friend offered to cure Samuel Pepys’s fever if he sent nail clippings and locks of hair.

1773 Boswell and Johnson dined on “a very good soup, a boiled leg of lamb and spinach, a veal pye, and a rice pudding.”

1819 Keats and Coleridge met just once, by chance, while both were walking on this day on Hampstead Heath. The young Keats was impressed and amused by the great, white-maned man, then under a doctor’s care for opium addiction: “In these two miles he broached a thousand things,” among them nightingales, dreams, mermaids, and sea monsters. “I heard his voice as he came towards me—I heard it as he moved away—I heard it all the interval.” Coleridge, meanwhile, was so busy talking he hardly noticed this “loose, slack, not well-dressed youth,” but later he would claim to have felt “death in the hand” of the young poet, who was felled by tuberculosis less than two years later.

1953 William Peden, in the Saturday Review, on two collections by young New Yorker short-story writers: J. D. Salinger is “occasionally too aware of the fact that he is a monstrous clever fellow,” while John Cheever’s “less spectacular” stories often “improve with rereading, which is not usually true of a Salinger piece.”

1954 In Paris, Julia Child tried to make a beurre blanc for sea bass that, to her “quite hurt surprise,” just wouldn’t blanc.

1961 In Jerusalem, Hannah Arendt, on assignment from The New Yorker, attended the first day of the trial of former Nazi Adolf Eichmann for his role in organizing the Holocaust. Writing her husband in New York (who, like her, had fled the Nazis) she expressed an immediate disgust for Eichmann, a “ghost in a glass cage,” as well as for the entire theater of the trial. Her coldly ironic account of the proceedings, Eichmann in Jerusalem, published two years later, ignited a controversy (one that still simmers) about her portrait of the “banality of evil” and of the role of Jewish Councils during the war.

1965 Undaunted by a plea from William Shawn that it would “thrust” the New York Herald Tribune “into the gutter,” New York magazine, then the Trib’s Sunday supplement, gleefully published “Tiny Mummies!,” the first of a two-part series by the young Tom Wolfe that mocked The New Yorker as a musty monastery led by the rumpled, whispering Shawn, reverently preserving the traditions—and the endless luxury advertising pages—of a magazine that, Wolfe argued, had never been that good to begin with.

April 12

BORN: 1916 Beverly Cleary (Henry Huggins, Beezus and Ramona), McMinnville, Ore.

1947 Tom Clancy (The Hunt for Red October, Patriot Games), Baltimore, Md.

DIED: 1988 Alan Paton (Cry, the Beloved Country), 85, Botha’s Hill, South Africa

1991 James Schuyler (The Morning of the Poem, A Nest of Ninnies), 67, New York City

1802 The letter has been lost to history, but Dorothy Wordsworth’s biographers have guessed, based on her response in her journals—“Every question was like the snapping of a little thread about my heart—I was so full of thought of my half-read letter and other things”—that on this day she learned of her beloved brother William’s engagement to her dear friend Mary Hutchinson. The perennial fascination with discerning the boundaries of affection among poet, sister, and wife—they continued to share a household for nearly fifty years—has extended to the poem he wrote this same day, “Among all lovely things my Love had been”: was the Love he spoke of meant for his fiancée, his sister, or both?

1850 When Charlotte Brontë’s publishers sent her a box of books including three by Jane Austen, they might not have known she already had an opinion on the author. “I should hardly like to live with her ladies and gentlemen in their elegant but confined houses,” she had written George Henry Lewes two years before when he recommended her next book after Jane Eyre be less “melodramatic” and more like Austen. And reading Emma in 1850 didn’t change her mind: “Her business is not half so much with the human heart as with the human eyes, mouth, hands and feet,” she explained on this day, “but what throbs fast and full, though hidden, what the blood rushes through, what is the unseen seat of Life and the sentient target of Death—this Miss Austen ignores.” She added, “If this is heresy—I cannot help it.”

1871 From his window, Edmund de Goncourt rooted for the French army against the “odious tyranny” of the revolutionary Paris Commune.

1903 On Easter Sunday, Jack London accidentally cut off the tip of his thumb.

2010 Operating out of a tiny office in New York’s Bellevue Hospital with the mandate to bridge the gap between medicine and literature, the Bellevue Literary Press had published just a couple of dozen books when one of its first fiction releases, Paul Harding’s Tinkers, was plucked from obscurity for the 2010 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, the first small-press book to win in almost twenty years. Even before its prize Tinkers had stirred word-of-mouth enthusiasm for the intensity of its attention to memory and the senses, with Transcendentalist echoes that make it a spiritual cousin to the Pulitzer winner of five years before, Gilead, by Harding’s former teacher Marilynne Robinson.

2010 Eight years after Yann Martel’s Life of Pi won the Booker Prize, the New York Times’s Michiko Kakutani called his follow-up novel, Beatrice and Virgil, “every bit as misconceived and offensive as his earlier book was fetching.”

April 13

BORN: 1906 Samuel Beckett (Waiting for Godot, Molloy), Dublin

1909 Eudora Welty (The Collected Stories, Delta Wedding), Jackson, Miss.

DIED: 1993 Wallace Stegner (Angle of Repose, Crossing to Safety), 84, Santa Fe, N.M.

2006 Muriel Spark (The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, Memento Mori), 88, Florence, Italy

1877 Never shy of concocting literary publicity, the young Guy de Maupassant placed an unsigned squib into the République des lettres advertising a dinner at which “six young and enthusiastic naturalists destined for celebrity” would honor their masters, Flaubert, Zola, and Edmond de Goncourt, with a menu inspired by their works, including “Potage purée Bovary” and “Liqueur de l’Assommoir.” The dinner place, at Paris’s Restaurant Trapp; the menu, though, was likely fictional, and of the young writers only two, J.-K. Huysmans and, naturally, Maupassant himself, would achieve any lasting literary celebrity.

1924 Among the few facts known about one of the most widely read, or at least distributed, authors in American history is his birth date. Born on this day in Los Angeles, Jack T. Chick, by his own account, was a troublemaking youth with a hobby in drawing until he found the Lord and published Why No Revival?, the first “Chick tract” in a series that now numbers in the hundreds, with over half a billion “soul winning” copies in print. Tiny, vivid comic books preaching hellfire for sinners and nonbelievers, especially for the Vatican’s minions of Satan, Chick tracts can traditionally be found piled up at bus stations and in the collections of hipsters transfixed by the vigor of the hate they contain.

1924 In response to Franz Kafka’s question about his tubercular larynx, “I wonder what it looks like inside?” his nurse responded, “Like the witch’s kitchen.”

1929 Reader “H.W.” wrote to the New Statesman, regarding Proust’s Cities of the Plain, that sexual “inversion” “does not belong to fiction, in spite of the prevailing craze for decadent literature.”

1933 Robert M. Coates, in The New Yorker, on Nathanael West’s Miss Lonelyhearts: “the crispest and the cleverest, the most impishly ironical and sharply epigrammatic book I’ve read in months and months.”

1940 In the third of his fifty-eight years as a staff writer at The New Yorker, Joseph Mitchell profiled McSorley’s, the oldest saloon in New York City, an establishment that trafficked largely in ale, onions, gloomy fellowship, and vigilantly sustained traditions, including a refusal to admit women that would stand until the Supreme Court intervened. A few years later, the business gave its name to Mitchell’s first book, McSorley’s Wonderful Saloon, a collection of portraits of the city’s eccentrics and battered bohemians who, like McSorley’s and Mitchell himself, pursued their idiosyncrasies with unassuming persistence.

1963 Flannery O’Connor confessed to a friend, “The other day I postponed my work an hour to look at W. C. Fields in Never Give a Sucker an Even Break.”

April 14

BORN: 1897 Horace McCoy (They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?), Pegram, Tenn.

1961 Daniel Clowes (Ghost World, Eightball), Chicago

DIED: 1964 Rachel Carson (The Sea Around Us, Silent Spring), 56, Silver Spring, Md.

1986 Simone de Beauvoir (The Second Sex, The Mandarins), 78, Paris

1824 When he returned to Philadelphia after years on the American frontier, John James Audubon hoped he might find a publisher for his paintings of the country’s birds. He found admirers, but Alexander Lawson, likely the only American engraver who could have handled the job as Audubon imagined it, was not among them. Roused from his bed to meet the artist, Lawson told him his pictures “were ill drawn, not true to nature, and anatomically incorrect.” When Audubon protested later, “Sir, I have been instructed seven years by the greatest masters in France,” Lawson replied, “Then you have made damned bad use of your time.” Rebuffed in Philadelphia, Audubon had to travel to Great Britain to find the engravers and patrons to produce his lavish Birds of America.

1865 In Henry and Clara, the first of his novels set in the political history of Washington, D.C., Thomas Mallon dramatized the night on which a forgotten couple was taken up and then tossed aside by the caprices of history. Already a bit of a scandal as a stepbrother and -sister engaged to be married, Henry Rathbone and Clara Harris, the Lincolns’ guests in their box at Ford’s Theatre, were bloodied bystanders at the assassination and were never the same afterward, Henry in particular. Stabbed nearly to death by the fleeing Booth, he slowly went mad and eighteen years later staged a bizarre reenactment of the tragedy with his wife as victim.

1923 James Joyce attended a rugby match between France and Ireland at Stade Colombes in Paris.

1939 For the first time, George Orwell’s goat Muriel gave a full quart of milk.

1952 Published: Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison (Random House, New York)

1965 Certain he had written an unprecedented masterpiece, Truman Capote had to postpone completing the final section of his “nonfiction novel,” In Cold Blood, for nearly two “excruciating” years while the machinery of justice moved to its conclusion. Finally, though, Perry Smith, one of Capote’s main characters, wrote him that “April 14 you know is the date to drop thru the trap door,” and just after midnight on that day Smith and Dick Hickock were indeed hanged by the state of Kansas, giving Capote, in attendance at the request of the condemned, an ending for the book that begins with their murders of the Clutter family four and a half years before.

1975 Kenneth Tynan took tea in London with Mel Brooks, who had “stubby self-confidence radiating from every pore.”

April 15

BORN: 1843 Henry James (Portrait of a Lady, The Ambassadors), New York City

1878 Robert Walser (Jakob von Gunten, The Robbers), Biel, Switzerland

DIED: 1942 Robert Musil (The Man Without Qualities), 61, Geneva, Switzerland

2000 Edward Gorey (The Gashlycrumb Tinies), 75, Hyannis, Mass.

1719Published: The Life and Strange Surprizing Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner by Daniel Defoe (W. Taylor, London)

1842 Charles Dickens, traveling in the American Midwest, called the Mississippi the “beastliest river in the world.”

1862 Col. Thomas Wentworth Higginson, the abolitionist, poet, and essayist, must have expected some response from the aspiring authors he addressed in his April “Letter to a Young Contributor” in the Atlantic Monthly, but nothing like the short note he received, written in a peculiar bird-scrawl that began, “Are you too deeply occupied to say if my Verse is alive?” It appeared to be unsigned until he discovered a small sub-envelope within that contained a card with the shyly penciled name “Emily Dickinson.” Enclosed also were four poems, and his curious and encouraging response, as well as the ambivalence about publishing them he shared with their author, led to a three-decade correspondence with Dickinson, she playing a coy “Scholar” and he bewildered and moved by the flights of her mind.

1865 Working in Washington during the war, Walt Whitman developed an affectionate and personal admiration for President Lincoln, whom he often saw riding into town, but when news came of his assassination, Whitman was back in New York, where Broadway was “black with mourning” and the sky dripped with “heavy, moist black weather.” Turning his thoughts to poetry, he composed a number of memorials in the following months, including “O Captain, My Captain,” which gained an immediate popularity Whitman came to regret, and the great, exuberant elegy “When Lilacs Last in the Door-yard Bloom’d.”

1924 Rand McNally published the first edition of their bestselling road atlas, titled, for the time being, the Rand McNally Auto Chum.

1972 Hunter S. Thompson was intent on staying outside the clubby pack of politicos and journalists while covering the 1972 Democratic primaries for Rolling Stone, but when his favored underdog, Senator George McGovern, suddenly became the front-runner, the lines got a little blurred, as in a friendly phone exchange included in Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72, which began with McGovern’s young political director, Frank Mankiewicz, fresh from a surprise win in Wisconsin, declaring, to Thompson’s surprise, “We have it locked up!” and ended with Mankiewicz, after hearing Thompson’s difficulties finding a Wisconsin doc to inject him with his preferred cocktail of remedies, saying with concern, “Hunter, I get the feeling that you’re not very careful about your health.”

April 16

BORN: 1871 J. M. Synge (The Playboy of the Western World), Rathfarnham, Ireland

1922 Kingsley Amis (Lucky Jim, The Old Devils), London

DIED: 1689 Aphra Behn (The Rover, Oronooko), 48, England

1994 Ralph Ellison (Invisible Man, Shadow and Act), 80, New York City

1911 Apsley Cherry-Garrard and the Scott Antarctica party spent Easter in a “howling blizzard,” dining on tinned haddock and “cheese hoosh” and reading Bleak House.

1912 On a foggy night in London, only a day after news of the sinking of the Titanic, an odd and “quaint” figure surprised the editor of Nash’s Magazine in his darkened office: Joseph Conrad, the novelist and former seaman, who was agitated at the blame quickly falling on the crew of the ship. Would they publish an article by him? Four hours later, a cable from the magazine’s New York office replied, “Who is Conrad? Do not want his story.” (Undaunted, Conrad vented his anger at the arrogance of building a “45,000 ton hotel of thin steel plates to secure the patronage of, say, a couple of thousand rich people” in the English Review instead.)

1933 Precariously and unrewardingly employed as an art teacher in his hometown of Drohobycz, Poland, Bruno Schulz found an outlet for the vivid world inside his head in stories he embroidered with a richly mythologized history of the town. His friends pressed to get them published until finally the timid Schulz traveled to Warsaw to present them to a well-known writer, Zofia Nałkowska, and waited, trembling, for her response. It came by telephone just before he had to leave for his return train: “This is the most sensational discovery in our literature!” By the end of the year, the collection was published as Cinnamon Shops; not until 1963, two decades after Schulz’s murder by an SS soldier in Drohobycz, was it translated into English and acclaimed in the United States as The Street of Crocodiles.

1963 “My dear fellow clergymen”: so began the message Martin Luther King scribbled in the margins of newspapers in the Birmingham jail, where he was held for defying an injunction against protest in the city. While demonstrators in the streets of Birmingham faced the police dogs and fire hoses of the arch-segregationist “Bull” Connor, King expressed a growing frustration with those who had at times been his allies, the “white moderates” who had counseled patience rather than protest in their own open letter four days before. Little noted at the time, King’s passionately reasoned “Letter from Birmingham Jail” became his best-known piece of writing after the Birmingham campaign, with its dramatic images of assaulted protesters, grew into one of the most influential of the civil rights movement.

1972 Charlie Brown told Peppermint Patty that the “secret to living is owning a convertible and a lake.”

2002 Published: Everything Is Illuminated by Jonathan Safran Foer (Houghton Mifflin, Boston)

April 17

BORN: 1885 Isak Dinesen (Seven Gothic Tales, Out of Africa), Rungsted, Denmark

1928 Cynthia Ozick (The Shawl, The Puttermesser Papers), New York City

DIED: 1790 Benjamin Franklin (Autobiography, Poor Richard’s Almanack), 84, Philadelphia

1986 Bessie Head (A Question of Power), 48, Serowe, Botswana

1907 Edgar Rice Burroughs, still five years away from creating Tarzan and John Carter of Mars, was promoted to manager of the Stenographic Department at Sears, Roebuck, and Co. in Chicago.

1926 Experiencing “silent convulsions of joy” as his train from New York approached his ancestral home in Rhode Island, H. P. Lovecraft could hardly contain his “surges of ecstasy” at his arrival at “HOME—UNION STATION—PROVIDENCE!!!!” “There is no other place for me,” he wrote. “My world is Providence.” For two years he’d been doomed to the heterogeneous metropolis of Brooklyn, whose “hateful chaos” of “non-Nordic” races spurred in him what one biographer has called a “genocidal frenzy.” Released to the relative purity of Rhode Island (and from the marriage that had taken him to New York), Lovecraft never moved away again and in the next decade before his death channeled his genius for disgust into the most memorably unsettling of his tales of horror.

1926 Carrying an amateur camera but hoping to become a writer, Walker Evans, like so many other Americans of his generation, arrived in Paris in search of an artistic education and a bohemian life. Somehow, though, despite becoming a regular at Sylvia Beach’s Shakespeare & Company bookshop, he missed out on the “moveable feast.” Lonely and shy, he connected with none of the famed expatriates, and when offered an introduction to James Joyce refused it in fear of meeting the great man. But while he wrote little, he read a lot, and at the Paris cafés he learned how to observe: “I got my license at the Deux Magots,” he later wrote. “Stare. It is the way to educate your eye and more. Stare, pry, listen, eavesdrop. Die knowing something.”

1982 Dying of cancer, John Cheever steered his son Fred away from a career he was considering: “On librarians I do speak with prejudice. The profession in general has always seemed to me like the legitimization and financing of an impulse to collect old socks.”

2002 At the Elliott Bay Book Company in Seattle, Ben Marcus, author of the excellent Age of Wire and String, graciously corrected the author of this book, who had confused him with Ben Metcalf, author of the superb essay “American Heartworm.”

April 18

BORN: 1918 André Bazin (What Is Cinema?), Angers, France

1959 Susan Faludi (Backlash, Stiffed), Queens, N.Y.

DIED: 1945 Ernie Pyle (Here Is Your War, Brave Men), 44, Iejima, Japan

1964 Ben Hecht (The Front Page, A Child of the Century), 70, New York City

NO YEAR They may not be the details you recall most vividly from your school reading, but The Canterbury Tales contain as much useful information about medieval astronomy, a fascination of Chaucer’s, as they do about the methods for cuckolding a carpenter. In his introduction to the Man of Law’s Tale, for instance, the Host mentions the only specific date in the poem—“the eightetethe of Aprill”—and estimates from the latitude and the length of shadows that it is ten in the morning. Scholars ever since have speculated about the actual dates of this fictional pilgrimage, placing it anywhere from 1385 to 1394 and giving it any length from four days and three nights to a single day’s journey taken at a canter, a word derived, after all, from the “Canterbury gallop” used by monks on their way to the cathedral.

1800 “If you really must beat the measure, sir, let me entreat you to do so in time, and not half a beat ahead.” Such is the cold, whispered greeting that Stephen Maturin gives to Lieutenant Jack Aubrey—soon to become Captain Aubrey—in their first meeting, at a concert in Port Mahon, Minorca, in the opening pages of Patrick O’Brian’s Master and Commander. They part equally coldly that night but are reconciled the following morning by their common musical enthusiasm and a shared pot of chocolate. Soon Aubrey asks Maturin to be the ship’s surgeon on his new command, the HMS Sophie, and their durable alliance of opposites—Aubrey large, bluff, and cheerful; Maturin small and introspective—provides the emotional backbone of the twenty further volumes in O’Brian’s beloved Aubrey-Maturin series.

1927 Fitzgerald wrote Hemingway that the first line of “In Another Country,” “In the fall the war was always there but we did not go to it any more,” was “one of the most beautiful prose sentences I have ever read.”

1981 “She ate the egg. Then another egg.” And that’s when June Kashpaw began to decide that her bus ticket out of town would be just as good any other day and she could stick around with the man who had bought her a beer and peeled her an egg, and then another, and then another. The eggs felt lucky, and this man could be different. “You got to be,” she breathed to him. “You got to be different.” Got to be or not, he turns out to be beside the point: it’s June who feels different, pure and naked like an egg under her crackling skin, and able to walk across the fields in the deep April snow, even as it buries her, in the sudden blizzard that opens Louise Erdrich’s Love Medicine.

April 19

BORN: 1900 Richard Hughes (A High Wind in Jamaica, In Hazard), Weybridge, England

1943 Rikki Ducornet (The Jade Cabinet), Canton, N.Y.

DIED: 1824 Lord Byron (Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage), 36, Missolonghi, Ottoman Empire

1882 Charles Darwin (On the Origin of Species), 73, Downe, England

1854 Henry David Thoreau declined a neighbor’s offer of a two-headed calf: “I am not interested in mere phenomena.”

1862 Lionel Tennyson, age eight, explained to a visitor to the household, Lewis Carroll, the conditions under which he would show Carroll some poems he had written: Carroll must play chess with him, and must allow Lionel to give him “one blow on the head with a mallet.”

1891 Following the line “I am sleepy, and the oozy weeds about me twist,” Herman Melville, seventy-one years old and five months from his death, added the words “End of Book.” He may have intended that line, the final one in a ballad called “Billy in the Darbies,” as the end of his book, but the book itself, Billy Budd, was unfinished and would remain so. The first novel he’d written in three decades, it was only discovered as a manuscript among his papers after nearly three more decades, when it was acclaimed as his last masterpiece.

1913 The Athenaeum on Sigmund Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams: “The results he reaches are hardly commensurate with the labour expended, and reveal a seamy side of life in Vienna which might well have been left alone.”

1951 Noel Coward had “nearly finished Little Dorrit—what a beastly girl, but what a wonderful novel.”

1956 The long friendship between Albert Murray and Ralph Ellison began in New York during the war when they realized they both, as southern transplants and African American writers, “had accepted the challenge of William Faulkner’s complex literary image of the South,” as Murray later put it. But by 1956 they were losing patience with Faulkner. “Nuts!” Ellison wrote from Rome about Faulkner’s “Go slow now” essay about civil rights in Life. “He thinks that Negroes exist simply to give ironic overtone to the viciousness of white folks.” Murray, replying on this day from Casablanca, where he was stationed with the air force, was more blunt: “Son of a bitch prefers a handful of anachronistic crackers to everything that really gives him a reason not only for being but for writing. I’m watching his ass but close forevermore.”

April 20

BORN: 1950 Steve Erickson (Days Between Stations, Zeroville), Los Angeles

1953 Robert Crais (L.A. Requiem, The Two-Minute Rule), Independence, La.

DIED: 1912 Bram Stoker (Dracula, The Lair of the White Worm), 64, London

1996 Christopher Robin Milne (The Enchanted Place), 75, Totnes, England

1746 Giacomo Casanova was a seducer not just of women but of patrons. Born poor, he had by the age of twenty-one already been a lawyer, a clergyman, a soldier, and finally a mediocre violinist when, after fiddling at a wedding in Venice, he retrieved a letter a nobleman dropped while stepping into his gondola. The nobleman offered him a ride home but suffered a stroke along the way, and Casanova, taking charge of his recovery and convincing him meanwhile that he was a master of the occult, made himself so useful that the nobleman—a Venetian senator, it turned out—adopted him as a son and, “at one bound,” as he recalled in his Story of My Life, raised him into the idle pleasures of the nobility.

1827 Charles and Alfred Tennyson, ages eighteen and seventeen, celebrated the publication of Poems by Two Brothers by riding to the coast and shouting their verses into the wind and waves.

1926 When The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man appeared in 1912, its author, James Weldon Johnson, thought it would make more of a splash published anonymously so it could be taken as the true confession of a black narrator who had passed into the white world. As it turned out, the novel hardly made a splash at all, receiving few sales or reviews (although the Nashville Tennessean did go to the trouble of declaring its title an impossibility: “once a negro, always a negro”). It was only in the following decade, during the flourishing of the Harlem Renaissance, that Blanche Knopf wrote Johnson on this day, “There is no question that we want The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man,” bringing back into print one of the subtlest and most challenging examinations of identity in American fiction.

1936 William Faulkner piloted a Waco F biplane in his first solo flight.

1984 At five in the morning on Good Friday in the opening pages of Richard Ford’s The Sportswriter, Frank Bascombe climbs over the cemetery fence behind his house to meet his ex-wife in remembrance of the birthday of their son, Ralph. Four years before, Ralph died at the age of nine, and two years after that Frank and “X,” as she’s known in the book, were divorced. Frank has brought a poem to read this year at Ralph’s grave: Theodore Roethke’s “Meditation,” a poem he likes and she dislikes for its assurance of the happiness that can be found in the everyday, an assurance that will be tested throughout The Sportswriter and the Bascombe novels that follow, Independence Day and The Lay of the Land.

April 21

BORN: 1816 Charlotte Brontë (Jane Eyre, Villette), Thornton, England

1838 John Muir (The Mountains of California), Dunbar, Scotland

DIED: 1910 Mark Twain (Life on the Mississippi, Pudd’nhead Wilson), 74, Redding, Conn.

1946 John Maynard Keynes (The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money), 62, Firie, England

129 Many have noticed that on April 21, the traditional anniversary of the founding of Rome, the open oculus at the top of the rotunda in the city’s Pantheon causes a circle of sunlight to shine on the temple’s doorway. Did the emperor Hadrian, who oversaw the building’s completion, arrange to have his ceremonial entrance on this date so illuminated? In Marguerite Yourcenar’s novel Memoirs of Hadrian, the emperor speaks with pride of the temple’s dedication and of the “disk of daylight . . . suspended there like a shield of gold.” As she mentions in her fascinating afternotes to the novel, Yourcenar visited the Pantheon herself on that same day of the year to check where the sunlight would fall.

1883 In remarks he’d later disown, Oscar Wilde described Algernon Swinburne as “a braggart of vice, who has done everything he could to convince his fellow citizens of his homosexuality and bestiality, without being in the slightest degree a homosexual or a bestializer.”

1992 “It was,” Mr. McAlister, the faculty adviser to the Student Government Association, has to admit, “the most interesting election I’d seen in my nine years at Winwood.” There’s Tracy Flick, smoldering with “110 pounds of the rawest, nakedest ambition” (and fresh off a scandalous fling with her English teacher); Paul Warren, the genial varsity fullback and Mr. M’s secret protégé; and the wild card, Paul’s sister, Tammy, whose campaign slogan is “Who cares about this stupid election?” And there’s Mr. M himself, who drops two crucial votes in a trash can on election day and ruins his life. Before Reese Witherspoon and Matthew Broderick made Tracy and Mr. M their own, there was Tom Perrotta’s Election, a breezily challenging novel about messy American democracy in the Bush-Clinton era.

1995 A mentor to his favorite cartoonists but competitive with them all, Charles M. Schulz developed a particularly affectionate friendship with Lynn Johnston, whose For Better or For Worse approached his Peanuts in popularity for a time. Her realistic strip, like few others, followed its characters through real time, and eventually Johnston had to deal with death, beginning with the sheepdog Farley, who died in this day’s strip after rescuing little April Patterson from a swollen river. “You cannot kill off the family dog,” Schulz told Johnston when she first previewed the storyline for him. “If you do this story, I am going to have Snoopy get hit by a truck and go to the hospital, and everybody will worry about Snoopy, and nobody’s going to read your stupid story.”

April 22

BORN: 1899 Vladimir Nabokov (Laughter in the Dark, Lolita), St. Petersburg, Russia

1923 Paula Fox (Desperate Characters, Borrowed Finery), New York City

DIED: 1984 Ansel Adams (Parmelian Prints of the High Sierra), 82, Monterey, Calif.

1996 Erma Bombeck (The Grass Is Always Greener over the Septic Tank), 69, San Francisco

1848 Having forgotten her birthday the day before, Charlotte Brontë lamented, “I am now 32. Youth is gone—gone—and will never come back.”

1910 One of Sigmund Freud’s most famous—and favorite—patients was one he only knew from a book. Daniel Paul Schreber, a judge in Leipzig who had suffered a mental breakdown, wrote Memoirs of My Nervous Illness to argue (successfully) for release from his asylum in 1902; Freud was so intrigued by his account he jokingly wrote Carl Jung on this day that Schreber “should have been made a professor of psychiatry and director of a mental hospital.” It’s no surprise he was drawn to the book: Schreber’s fantastic and detailed visions—of turning into a woman, of being penetrated by rays and by crowds of people, of his “soul murder” at the hands of his former doctor—provide a rich text for Freud’s analysis in The Schreber Case of the source of the patient’s paranoia. (Surprise: it’s his father.)

1949 After his ex-con friend Little Jack Melody crashed his car in a police chase—with Ginsberg and a load of stolen jewelry and furs in the back seat—twenty-one-year-old Allen Ginsberg was arrested for grand larceny and attempting to run over a policeman.

1951 The legend of Jack Kerouac’s frenzied composition of On the Road both is and isn’t true. He spent years drafting and revising the novel, but it is true that for three weeks, ending on this day, he typed a complete, 125,000-word draft on a 120-foot roll of paper he had taped together. Soon after, he proudly unrolled the scroll in the office of Robert Giroux, to that point his champion in New York publishing, who replied, “How the hell can the printer work from this?” His revised version finally saw print in 1957, but fifty years later the draft was published as On the Road: The Original Scroll, with the characters Dean Moriarty and Carlo Marx restored to their original names, Neal Cassady and Allen Ginsberg.

1973 Concrete Island is not the only novel of J. G. Ballard’s that begins with an automobile crash. But unlike the erotic violence of Crash, this accident, in which a blown tire sends Robert Maitland’s Jaguar onto the embankment of a highway interchange in central London, leaves its victim unscathed. And what follows is less a story of violence than of isolation, of a man marooned in the midst of a metropolis. Unable at first to attract a rescuer from the flow of traffic, as he’s left to his own resources and those of his few tramp neighbors, he becomes unwilling to leave his concrete island on any terms but his own.

April 23

BORN: 1895 Ngaio Marsh (Enter a Murderer), Christchurch, New Zealand

1942 Barry Hannah (Airships, Geronimo Rex), Meridian, Miss.

DIED: 1915 Rupert Brooke (1914 and Other Poems), 27, Skyros, Greece

1996 P. L. Travers (Mary Poppins), 96, London

1374 Has a poet been more glamorously compensated than when Edward III, during the feast of St. George at Windsor Castle, granted Geoffrey Chaucer a pitcher of wine a day for life, to be picked up daily from the king’s butler? It is not certain that the reward—extravagant even for its time—was for poetry; some have connected it instead to his recent mission to Florence or his new position as controller of the Wool Custom. Whatever its cause, the impracticality of the gift was such that four years later Edward’s successor, Richard II, turned it into a regular cash payment.

1616 Did Shakespeare and Cervantes, the two great founders of modern literature, really die on the same day, as is often said? Not quite: Shakespeare died on this day in the old Julian calendar, while Cervantes died eleven days earlier, on April 22 in the Gregorian calendar, and was buried on the 23rd.

1857 Nearing forty, Henry David Thoreau might have felt he had encountered his own youthful self in the person of a twenty-year-old woman when he met Kate Brady. An admirer of Walden and a lover of nature, she told Thoreau that like him she wanted to “live free.” “Her own sex, so tamely bred, only jeer at her for entertaining such an idea,” Thoreau wrote a week later, “but she has a strong head and a love for good reading, which may carry her through.” Then, as if to banish any thought that she might be a companion for him, he added, “How rarely a man’s love for nature becomes a ruling principle with him, like a youth’s affection for a maiden, but more enduring! All nature is my bride.”

1916 His new job as head of the Surety Claims Department of the Hartford Accident and Indemnity Company often took Wallace Stevens, who had just begun publishing poems in literary journals, on the road, and on Easter Sunday he wrote his wife from Miami. “Florida,” he reported, “is not really amazing in itself but in what it becomes under cultivation . . . There are brilliant birds and strange things but they must be observed,” the stirrings of a thought he’d expand and complicate twenty years later in his portrait, in “The Idea of Order at Key West,” of a singer who “Knew that there never was a world for her / Except the one she sang and, singing, made.”

1975 Longtime correspondents Barbara Pym and Philip Larkin met in person for the first time for lunch, Pym having informed Larkin beforehand, “I shall probably be wearing a beige tweed suit or a Welsh tweed cape if colder. I shall be looking rather anxious, I expect.”

April 24

BORN: 1815 Anthony Trollope (Barchester Towers, The Way We Live Now), London

1940 Sue Grafton (“A” Is for Alibi, “B” Is for Burglar), Chicago

DIED: 1731 Daniel Defoe (Robinson Crusoe, Moll Flanders), c. 70, London

1942 L. M. Montgomery (Anne of Green Gables, Emily of New Moon), 67, Toronto

1814 Edward Barrett sent his eight-year-old daughter, Elizabeth, ten shillings in exchange for a poem “on virtue,” calling her the “Poet Laureate of Hope End.”

1895 “I had resolved on a voyage around the world, and as the wind on the morning of April 24, 1895, was fair, at noon I weighed anchor, set sail, and filled away from Boston.” Not far past the docks, Joshua Slocum, piloting the thirty-seven-foot sloop Spray alone, passed a steamship that had broken on the rocks and noted, “I was already farther on my voyage than she.” Slocum sailed 46,000 more miles before returning to New England over three years later as the first to circumnavigate the globe solo. By then the newspapers that were his early sponsors had lost interest in his dispatches, but his full account, published as Sailing Alone Around the World, was an immediate international success and remains one of the finest of adventure yarns.

1916 The factions of Irish nationalism were many, and when word reached him in England of the Rising in Dublin against the British that began on this Easter Monday, W. B. Yeats didn’t think much of some of the conspirators—a dreamer, a drunk, and a madwoman among them, he thought. But by May, when British firing squads began executing the rebels, he had already composed the famous refrain—“a terrible beauty has been born”—of the poem “Easter, 1916,” which he would complete in September. It wasn’t until 1920, though, with World War I over and the Irish War of Independence begun, that he found the times right to publish his ambivalent song of martyrdom.

1944 With Under the Volcano, his own novel of alcoholic descent, still unpublished, Malcolm Lowry wrote a friend, “Have you read a novel The Lost Weekend by one Charles Jackson, a radioman from New York? It is perhaps not a very fine novel but admirably about a drunkard and hangovers and alcoholic wards as they have never been done (save by me of course).”

1963 Eight years after he first mocked up a tiny book called Where the Wild Horses Are, Maurice Sendak drafted the opening lines of what would be his first solo picture book. The story began, “Once a boy asked where the wild horses are. Nobody could tell him,” and it involved a magic garden and a mother who turned into a wolf. Within a month, though, the horses had become “things”—“I couldn’t really draw horses,” Sendak said—inspired by the frightening relatives who invaded his childhood home on Sundays, saying, “You’re so cute I could eat you up,” and in the fall Where the Wild Things Are was published, to great consternation and delight.

April 25

BORN: 1949 James Fenton (The Memory of War), Lincoln, England

1952 Padgett Powell (Edisto, The Interrogative Mood), Gainesville, Fla.

DIED: 1944 George Herriman (Krazy Kat), 63, Los Angeles

2006 Jane Jacobs (The Death and Life of Great American Cities), 89, Toronto

387 St. Augustine may have invented the modern autobiography with his Confessions, but his own autobiography, or at least the modern part of it, ends midway through that book with the words describing this day: “And we were baptized, and anxiety for our past life vanished from us.” To that point Augustine’s path has taken him through sin and spiritual yearning to the moment when he saw the light in a garden in Milan; a year later that serene vision of his sins absolved was granted by his baptism in the same city. The Confessions still has four books remaining at that point, but the confessing is over: the rest is less about Augustine the man than about his God.

1811 Jane Austen, asked by her sister about Sense and Sensibility, soon to be published, replied, “I am never too busy to think of S&S. I can no more forget it, than a mother can forget her sucking child.”

1929 With his second novel on its way, Henry Green was able to make his engagement with Mary Biddulph official when their fathers, after months of negotiation, settled on an £1,800 annual income for the young couple.

1931 “Constant Reader,” in The New Yorker, on Dashiell Hammett’s The Glass Key: “All I can say is that anybody who doesn’t read him misses much of modern America . . . Dashiell Hammett is as American as a sawed-off shotgun.”

1983 It took only three days for one of the greatest scoops in modern journalism to unravel. On April 22, the German newsweekly Stern announced the discovery of a treasure trove for historians: the diaries kept by Adolf Hitler between 1932 and 1945, which had been authenticated in a Swiss bank vault by experts swayed by the sight of over sixty handwritten notebooks, a number no forger, surely, would have had the audacity or stamina to fabricate. The next day the distinguished historian Hugh Trevor-Roper wrote that history as we knew it would “have to be revised,” but by the 25th, when Stern and Newsweek first published excerpts, the fraud was coming undone. (Among the clues: the A in the Gothic initials “AH” glued onto each volume was, in fact, an F.) The diaries, it was soon revealed, were a collaboration between journalist Gerd Heidemann and career forger Konrad Kujau.

2008 Michel Faber, in the Guardian, on James Kelman’s Kieron Smith, Boy: “I suspect Kelman knew exactly what he was doing. And what he has done here is both revolutionary and very, very dull.”

April 26

BORN: 1889 Ludwig Wittgenstein (Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus), Vienna

1914 Bernard Malamud (The Natural, The Fixer), Brooklyn

DIED: 1991 A. B. Guthrie Jr. (The Big Sky, The Way West), 90, Choteau, Mont.

2004 Hubert Selby Jr. (Last Exit to Brooklyn, Requiem for a Dream), 75, Los Angeles

1336 Did the poet Petrarch invent mountaineering when he ascended Mont Ventoux? Some historians have claimed it, but some have questioned whether he climbed the mountain—best known now as one of the great cyclist’s challenges in the Tour de France—at all. The fame of his adventure rests on an account he claimed to have written the night of his descent: full of earthly pleasure at the view from the 1,912-meter summit, he opened his pocket copy of St. Augustine’s Confessions and was chastened and exalted by the passage he turned to by chance: “And men go to admire the high mountains, the vast floods of the sea, the huge streams of the rivers, the circumference of the ocean and the revolutions of the stars—and desert themselves.”

1853 Reading Montaigne in bed, Flaubert wrote to Louise Colet: “I know of no more soothing book, none more conducive to peace of mind. It is so healthy, so down to earth!”

1884 Leo Tolstoy, one of Russia’s best-known men, set out to visit a bookshop in Moscow but turned back when no one on the streetcar would change a ten-ruble note. “They all thought I was a swindler.”