May is blooming and fertile, spring in its full flower. Unlike the storms of March and the “uncertain glory” of April, Shakespeare’s May, with its “darling buds,” is always sweet, and ever the month for love. Traditionally—before the international labor movement claimed May 1st in honor of the Haymarket riot—May Days were holidays of love too, white-gowned fertility celebrations. It’s on a May Day that Thomas Hardy, always attuned to ancient rites, introduces Tess Durbeyfield, whose “bouncing handsome womanliness” among the country girls “under whose bodices the life throbbed quick and warm” still reveals flashes of the child she recently was.

May has long been the month for mothers as well as maidens, even before Anna Jarvis chose the second Sunday in May in 1908 for Mother’s Day to honor the death of her own mother. The mother of them all, the Virgin Mary, was celebrated for centuries as the Queen of May, and in “The May Magnificat” Gerard Manley Hopkins reminds us that “May is Mary’s month,” and asks why. “All things rising,” he answers, “all things sizing / Mary sees, sympathizing / with that world of good, / Nature’s motherhood.”

May’s meanings can get to be too much, though. When the mother in The Furies, Janet Hobhouse’s fictional memoir of a life caught up in isolated family dependence, chooses Memorial Day to end her own life, her daughter mournfully riffs on May in an overdetermined frenzy of meaning: “month of mothers, month of Mary, month of heroes, the beginning of heat and abandonment, of the rich leaving the poor to the cities, May as in Maybe Maybe not, as in yes, finally you may, as in Mayday, the call for help and the sound of the bailout, and also, now that I think of it, as in her middle name, Maida.”

The “may” in “May” had another meaning for Elizabeth Barrett, who wrote to Robert Browning from her invalid’s bed during the “implacable weather” of March that “April is coming. There will be both a May & a June if we live to see such things, & perhaps, after all, we may.” She wasn’t only speaking of better weather coming: since they began to write each other in January they had spoken of meeting in person for the first time—he especially—but she, without refusing, had put him off, excusing herself as “a recluse, with nerves that have been all broken on the rack, & now hang loosely.” When May arrived, she wrote him, “Shall I have courage to see you soon, I wonder! . . . But oh, this make-believe May—it can’t be May after all!” And then on May 20 she met him, beginning a secret courtship, against her father’s wishes, that ended in their elopement in September of the following year.

RECOMMENDED READING FOR MAY

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll (1865)  She may have met a March Hare that was mad as a hatter, but it was in the month of May—the birthday month of Alice Liddell, Charles Dodgson’s model for his heroine—that Alice followed a rabbit with a watch in his waistcoat pocket down a hole and began her adventures underground.

She may have met a March Hare that was mad as a hatter, but it was in the month of May—the birthday month of Alice Liddell, Charles Dodgson’s model for his heroine—that Alice followed a rabbit with a watch in his waistcoat pocket down a hole and began her adventures underground.

Tess of the d’Urbervilles by Thomas Hardy (1891)  Angel is first drawn, fleetingly, to young Tess at a May Day dance at Whitsun time. By late spring two years later, her womanly blossoming is almost overwhelming—she’s working alongside him as a milkmaid, for goodness sake—but by then Hardy has arranged their fates to make her bloom a cruel joke on both of them.

Angel is first drawn, fleetingly, to young Tess at a May Day dance at Whitsun time. By late spring two years later, her womanly blossoming is almost overwhelming—she’s working alongside him as a milkmaid, for goodness sake—but by then Hardy has arranged their fates to make her bloom a cruel joke on both of them.

Death in Venice by Thomas Mann (1912)  A false taste of summer in May in his northern home drives the middle-aged writer Gustav Aschenbach south for freshness and inspiration to Venice, where he will be drawn into an impotent attraction to a young Polish boy amid the humid miasma of cholera.

A false taste of summer in May in his northern home drives the middle-aged writer Gustav Aschenbach south for freshness and inspiration to Venice, where he will be drawn into an impotent attraction to a young Polish boy amid the humid miasma of cholera.

Lucky Jim by Kingsley Amis (1954)  There’s no better cure for end-of-term apathy than the campus novel that, for better or worse, launched the genre (along with Randall Jarrell’s Pictures from an Institution, published the same year). But it may make you never want to go back to class at all, especially if you’re lecturing, miserably, on medieval history at a provincial English university.

There’s no better cure for end-of-term apathy than the campus novel that, for better or worse, launched the genre (along with Randall Jarrell’s Pictures from an Institution, published the same year). But it may make you never want to go back to class at all, especially if you’re lecturing, miserably, on medieval history at a provincial English university.

“The Whitsun Weddings” by Philip Larkin (1964)  Amis based Lucky Jim on, and dedicated it to, his good friend Larkin, who made his own mark on postwar British culture with this ambivalent ode to the hopeful mass pairing-up of springtime, three years before the Kinks captured the same lonely-in-the-city melancholy in “Waterloo Sunset.”

Amis based Lucky Jim on, and dedicated it to, his good friend Larkin, who made his own mark on postwar British culture with this ambivalent ode to the hopeful mass pairing-up of springtime, three years before the Kinks captured the same lonely-in-the-city melancholy in “Waterloo Sunset.”

Frog and Toad Are Friends by Arnold Lobel (1970)  The lesson of “Spring,” the opening tale in Lobel’s thrillingly calm series for early readers, is, apparently, that there is honor in deception, as Frog fools hibernating Toad into joining him on a fine April day by tearing an extra page off the calendar to prove it is, in fact, May.

The lesson of “Spring,” the opening tale in Lobel’s thrillingly calm series for early readers, is, apparently, that there is honor in deception, as Frog fools hibernating Toad into joining him on a fine April day by tearing an extra page off the calendar to prove it is, in fact, May.

Awakenings by Oliver Sacks (1973)  Awed equally by chemistry and human adaptability, Sacks recorded in the second book of his remarkable career the moment in May 1969 when he began to administer a new “miracle drug” to a few dozen patients subdued for decades by a rare illness contracted in the ’20s.

Awed equally by chemistry and human adaptability, Sacks recorded in the second book of his remarkable career the moment in May 1969 when he began to administer a new “miracle drug” to a few dozen patients subdued for decades by a rare illness contracted in the ’20s.

Reborn: Journals & Notebooks, 1947–1963 by Susan Sontag (2008)  “I AM REBORN IN THE TIME RETOLD IN THIS NOTEBOOK,” sixteen-year-old Sontag scribbled on the inside cover of her journal for May 1949, marking a moment when she was colossally precocious—rereading Mann, Hopkins, and Dante—and falling in love for the first time, with a young woman in San Francisco.

“I AM REBORN IN THE TIME RETOLD IN THIS NOTEBOOK,” sixteen-year-old Sontag scribbled on the inside cover of her journal for May 1949, marking a moment when she was colossally precocious—rereading Mann, Hopkins, and Dante—and falling in love for the first time, with a young woman in San Francisco.

May 1

BORN: 1923 Joseph Heller (Catch-22, Something Happened), Brooklyn

1924 Terry Southern (Candy, The Magic Christian), Alvarado, Tex.

DIED: 1700 John Dryden (MacFlecknoe, Marriage à la Mode), 68, London

1978 Sylvia Townsend Warner (Lolly Willowes), 84, Maiden Newton, England

1841 Reviewing Dickens’s Barnaby Rudge in the middle of its serialization, Edgar Allan Poe correctly predicted the identity of the murderer.

1908 About to give his “The Poet of Democracy” lecture to a local literary society in Appleton, Wisconsin, Carl Sandburg confessed, “A sort of deviltry possesses me at times among these—to talk their slangiest slang, speak their homely, beautiful home-speech about all the common things—suddenly run a knife into their snobbery—then swing out into a crag-land of granite and azure where they can’t follow but sit motionless following my flight with their eyes.”

1934 The early comic-book adventures of Tintin are unthinkingly accepting of European stereotypes of foreign lands (in the regrettable Tintin in the Congo, to be precise), but when Hergé, Tintin’s young Belgian creator, turned to China as a subject for his fifth tale, his Catholic advisers wisely recommended he be less culturally careless, and introduced him to a visiting Chinese sculptor named Chang Chong Chen on this day. The two young artists hit it off immediately, and Hergé paid tribute to their friendship with a character named after his friend in The Blue Lotus. Nearly a half-century later, fact and fiction reversed: after Hergé had Tintin search for his old friend Chang in Tintin in Tibet, the real-life Chang, having survived the Cultural Revolution, reappeared in Belgium for a well-publicized reunion with Hergé.

1935 Israel Joshua Singer was always ahead of his younger brother, Isaac Bashevis: born a decade earlier, he was the first to find success in writing and the first to immigrate to America (where his novel Yoshe Kalb had already become a popular play). When his brother followed him to New York on this day, Israel Joshua met him at the dock, and a photograph of the two together appeared in the Forward, the city’s Yiddish newspaper where the elder brother worked, with the caption, “Two Brothers and Both Writers.” For years Isaac worked at the Forward under his brother’s shadow, but after Israel’s sudden death of a heart attack in 1944, it was the younger Singer who continued at the paper for more than half a century, and who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1978.

1941 If The Escapist had ended its run before this day, it would doubtless have disappeared like its countless, disposable comic-book peers. But all that changed, because on the 1st of May, in Michael Chabon’s The Adventures of Kavalier & Clay, Joe Kavalier and Sammy Clay saw Citizen Kane. Afterward, their ambition aflame with the possibilities of narration matched with image, Joe looked over at Sammy and said, “I want to do something like that.”

May 2

BORN: 1838 Albion W. Tourgée (A Fool’s Errand, Bricks Without Straw), Williamsfield, Ohio

1900 W. J. Cash (The Mind of the South), Gaffney, S.C.

DIED: 1519 Leonardo da Vinci (Treatise on Painting, Notebooks), 67, Amboise, France

1963 Van Wyck Brooks (The Flowering of New England), 77, Bridgewater, Conn.

1970 Though a son of Louisville himself, Hunter S. Thompson tried to put family ties aside when he returned for the ninety-sixth running of the local horse race. His self-appointed job was to pin down the “whole doomed atavistic culture that makes the Kentucky Derby what it is,” which meant embarking on a “vicious, drunken nightmare” inside the press box and out. He and his bearded British illustrator, Ralph Steadman, along for the ride for the first time, managed to miss, more or less, both the race itself and whatever crowd violence there was (the violence seemed mainly to be in Thompson’s head), but his scabrous report, “The Kentucky Derby Is Decadent and Depraved,” published in the short-lived Scanlan’s Monthly, became the first Thompson piece to earn the adjective he’d proudly wear the rest of his life: “gonzo.”

1981 Jim Williams did not deny that he shot Danny Hansford in the office of his carefully restored and furnished Savannah mansion shortly after midnight. He just said Danny shot first (and second and third). It wasn’t this murder that drew John Berendt to Savannah to write Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil: he had already fallen for the city and its mix of gossipy gentility and down-market style, and he already knew both the deceased, a volatile young hustler, and the wealthy man who would be convicted twice and acquitted once of shooting him. He was there to hear the tongues wagging before and after the crime, which is what makes his book so delicious—and kept it on the bestseller list for over four years.

1984 No one would think of George Orwell as a poet of the pastoral (he was drawn more to disgust), but listen to him: “Under the trees to the left of them the ground was misty with bluebells. The air seemed to kiss one’s skin. It was the second of May.” Readers of 1984 will likely recall this thrillingly unlikely rural interlude, when Winston meets Julia alone for the first time and she flings her scarlet chastity sash from the Junior Anti-Sex League aside in a sun-dappled forest grove. Of course their joys won’t last—Winston knows they won’t—but the liquid song of a thrush they hear in that grove stands in the novel as an uncorrupted life force that somehow exists outside the power of Big Brother.

1989 David Foster Wallace’s new habit of chewing tobacco, he explained to Jonathan Franzen, “is stupid and dangerous, and involves goobing big dun honkers every thirty seconds.”

May 3

BORN: 1469 Niccolò Machiavelli (The Prince, Discourses on Livy), Florence, Italy

1896 Dodie Smith (I Capture the Castle, The 101 Dalmatians), Whitefield, England

DIED: 1991 Jerzy Kozinski (Being There, The Painted Bird), 57, New York City

1810 Lord Byron did like to swim, and he liked to write about what he had swum. In 1809 he crossed the wide mouth of the Tagus River, near Lisbon, a feat his traveling companion John Hobhouse considered more daring than the one, undertaken a year later, that brought him greater fame, not least by his own efforts. Following the Greek myth of the youth Leander who swam every night to his lover, Hero, across the Hellespont, the strait dividing Europe from Asia, Byron and a ship’s lieutenant attempted the crossing themselves. Driven back once by cold and current, they tried again a week later and made the four-mile crossing in a little more than an hour, an achievement he celebrated in a short poem and mentioned again nearly a decade later in Don Juan. The hazardous current, he wrote to one friend, made him “doubt whether Leander’s conjugal powers must not have been exhausted in his passage to paradise.”

1939 Malcolm Cowley, in the New Republic, on John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath: “What one remembers most of all is Steinbeck’s sympathy for the migrants—not pity, for that would mean he was putting himself above them; not love, for that would blind him to their faults, but rather a deep fellow feeling.”

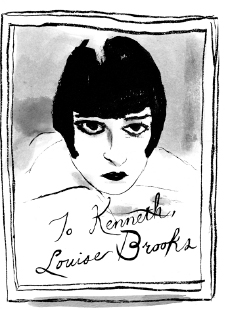

1978 After a visit to the Eastman archives in Rochester spent watching the silent films of Louise Brooks, “this shameless urchin tomboy, this unbroken, unbreakable porcelain filly” whose image had “run through my life like an unbroken thread,” Kenneth Tynan returned for a second day of conversations at a nearby apartment building with a tiny, elderly woman, barefoot in a nightgown and bed jacket: Louise Brooks. “You’re doing a terrible thing to me,” she said. “I’ve been killing myself for twenty years, and you’re going to bring me back to life.” For three days she recalled her years of notoriety and obscurity, flirted with her younger fan, and shared her own love of the movies, with Tynan taking notes for his classic New Yorker profile “The Girl in the Black Helmet,” which became the introduction to Brooks’s own sharp-witted book of memoir and film criticism, Lulu in Hollywood.

May 4

BORN: 1939 Amos Oz (Black Box, A Tale of Love and Darkness), Jerusalem

1949 Graham Swift (Waterland, Shuttlecock, Last Orders), London

DIED: 1973 Jane Bowles (Two Serious Ladies, In the Summer House), 56, Malaga, Spain

1852 “What day of the month is it?” asked the Hatter, looking at his watch. “Alice considered a little, and then said, ‘The fourth.’ ‘Two days wrong!’ sighed the Hatter. ‘I told you butter wouldn’t suit the works!’ ” It’s only natural that sensible Alice would know this date—it was the birthday of the girl who inspired the tale, Alice Liddell. She was ten when Charles Dodgson first told the story to the Liddell sisters on a rowboat, thirteen when he published Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland under the name Lewis Carroll, and nineteen when its sequel, Through the Looking-Glass, appeared, which included an acrostic poem that spells out “Alice Pleasance Liddell.”

1896 Why did Edith Wharton and her husband purchase a brownstone in an unfashionable Upper East Side neighborhood? “On account of the bicycling,” she explained.

1928 Virginia Woolf found her fame “becoming vulgar and a nuisance. It means nothing; and yet takes one’s time. Americans perpetually.”

1929 “You must be married at once very obtrusively,” Evelyn Waugh advised Henry Green on learning of his engagement. “A fashionable wedding is worth a four column review in the Times Literary Supplement to a novelist.”

1953 Under the supervision of Dr. Humphry Osmond, a Saskatchewan psychiatrist who later coined the term “psychedelic,” Aldous Huxley took mescaline for the first time at his home in Los Angeles. Overcome at first by lassitude, he walked with his wife and Osmond to the World’s Biggest Drug Store at Beverly and La Cienega boulevards, where, in an aisle of art books, the brushstrokes of Botticelli overwhelmed him with a splendor that made a drive later that evening to see the hilly vistas over Hollywood an anticlimax by comparison, a vision that became the centerpiece of his account of the experience, The Doors of Perception.

1976 Mike Royko had been battling the Daley Machine in his Chicago Daily News column for years, so making fun of Frank Sinatra and his “army of flunkies” for the free, around-the-clock police protection the Chicago police provided the singer at his hotel was no big deal. But Ol’ Blue Eyes didn’t think it was funny, writing Royko on this day to call him a “pimp” and ask “why people don’t spit in your eye three or four times a day.” Royko obligingly printed the letter in his next column and then auctioned off the original to the highest bidder, Vie Carlson of Rockford, Illinois. Three decades later, Vie, whose son Brad, as it happens, was in the music business too, drumming for Cheap Trick under the stage name Bun E. Carlos, brought her letter onto the PBS show Antiques Roadshow, where it was appraised at $15,000.

May 5

BORN: 1813 Søren Kierkegaard (Either/Or, Fear and Trembling), Copenhagen

1818 Karl Marx (The German Ideology, The Communist Manifesto), Trier, Prussia

DIED: 1988 Michael Shaara (The Killer Angels, For Love of the Game), 59, Tallahassee, Fla.

1997 Murray Kempton (Part of Our Time, The Briar Patch), 79, New York City

1593 With London scourged by plague and war, some looked for scapegoats among the city’s immigrants, and on this night a vicious poem was posted on the wall of a Dutch church, warning “you strangers that inhabit this land” that “we’ll cut your throats, in your temples praying.” The poem’s authors are unknown, but they were surely playgoers: the poem was signed “Tamberlaine,” the murderous hero of one Christopher Marlowe play, and it alluded to two of his other violent dramas: The Jew of Malta and The Massacre of Paris. The quarters of playwright Thomas Kyd were searched, but they turned up evidence of a different crime: atheist papers that Kyd, under torture, said were Marlowe’s. Ordered arrested for heresy on the 18th, Marlowe was dead on the 30th, killed in a mysterious brawl that has ever since been suspected to be an assassination.

1857 At a dinner at Boston’s Parker House, assembled by the publisher Moses Phillips, eight leading literary men, including Emerson, Longfellow, Lowell, and Oliver Wendell Holmes, met to found the Atlantic. “Imagine your uncle at the head of such guests,” blushed Phillips to his niece two weeks later. “It was the proudest moment of my life.”

1862 Arthur Blomfield, in search of a “young Gothic draughtsman who could restore and design churches and rectory-homes,” hired as an architectural assistant at £110 a year twenty-one-year-old Thomas Hardy, who had arrived in London three weeks before.

1943 Five days after his discharge from the army after recovering from a nervous breakdown, Mervyn Peake wrote to a friend he had made just before the war, Graham Greene, “I’ll be able to concentrate on Gormenghast. It’s a grand feeling.” Already known by this time as a painter and as “the greatest illustrator of his day,” Peake had spoken before to Greene of the novel he’d been working on. But when he sent him the final draft a few months later, Greene’s response was devastating: “I was very disappointed in a lot of it and frequently wanted to wring your neck because it seems to me you were spoiling a first class book by laziness.” Greene hadn’t given up on the book, though—he suggested they “duel” about it over whiskey—and after Peake’s thorough revisions it was published as Titus Groan, the first volume in his long-loved cult classic, the Gormenghast Trilogy.

1946 Caroline Gordon, in the New York Times, on The Portable Faulkner: “He writes like a man who so loves his land that he is fearful for the well-being of every creature that springs from it.”

May 6

BORN: 1856 Sigmund Freud (The Interpretation of Dreams), Freiberg in Mähren, Austrian Empire

1914 Randall Jarrell (The Woman at the Washington Zoo), Nashville, Tenn.

DIED: 1862 Henry David Thoreau (The Maine Woods), 44, Concord, Mass.

1919 L. Frank Baum (The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, Ozma of Oz), 62, Hollywood, Calif.

1850 Emily Dickinson—at least at the age of nineteen—wasn’t always a homebody by choice. With her mother laid up by acute neuralgia, Dickinson sat attentively by her side and remained there even when temptation called. “I heard a well-known rap,” she wrote a teenage confidant, “and a friend I love so dearly came and asked me to ride in the woods, the sweet still woods, and I wanted to exceedingly—I told him I could not go, and he said he was disappointed, he wanted me very much.” She conquered her tears, calling it “a kind of helpless victory,” and returned to her work, “humming a little air” until her mother was asleep, but then she “cried with all my might.” The young man who invited her out has never been identified.

1871 When the great man arrived in the Yosemite Valley, the word went out: “Emerson is here!” John Muir joined the crowd around him but was too awed to approach. Later, though, he sent a note inviting Emerson to stay for “a month’s worship” in the woods, and the next morning Emerson rode up to the hill to meet the young man. No longer shy, Muir made an eager guide and insisted that on his last night in the valley the author of “Nature,” though sixty-seven, more than twice his age, camp out with him under the giant trees of the Mariposa Grove. Emerson agreed, but when evening came those less adventurous in his party urged him instead into the staler comforts of an inn, disappointing Muir that his hero “was now a child in the hands of his affectionate but sadly civilized friends.”

1908 The imaginative materials that Marcel Proust would weave into the volumes of In Search of Lost Time started to come together in 1908. “Sickened” by his efforts to pastiche the styles of Balzac, Flaubert, and others, he turned instead to writing a series of fragmentary pieces. The subjects might have seemed disconnected, but his later readers would certainly recognize in them the connective tissue of his vast novel. “I have in hand,” he described the elements to a friend either on this day or the previous one, “a study on the nobility, a Parisian novel, an essay on Sainte-Beuve and Flaubert, an essay on women, an essay on pederasty (not easy to publish), a study on stained-glass windows, a study on tombstones, a study on the novel.”

1948 Italo Calvino, in L’Unità, on Primo Levi’s Se questo è un uomo (Survival in Auschwitz): a book of “authentic narrative power, which will remain . . . amongst the most beautiful of the literature of the Second World War.”

May 7

BORN: 1931 Gene Wolfe (The Book of the New Sun), New York City

1943 Peter Carey (Oscar and Lucinda), Bacchus Marsh, Australia

DIED: 1941 Sir James George Frazer (The Golden Bough), 87, Cambridge, England

1994 Clement Greenberg (“Avant-Garde and Kitsch”), 85, New York City

1911 The life of Albert Mathé, French journalist, began in 1943 at the age of thirty-two, when false papers and an identity card under that name were created by the French Resistance for Albert Camus, including a forged birth certificate that said Mathé was born on this day in Choisy-le-Roi, France, far from Camus’s own birthplace in Algeria. Camus had begun the war as a declared pacifist and spent its first years working on his novels The Stranger and The Plague while considering returning to Algeria, but late in 1943 he committed himself to staying in German-occupied Paris and joined the newspaper of the Resistance, Combat, as a writer and editor.

1932 At the height of his most prodigiously creative period, with The Sound and the Fury and As I Lay Dying recently published and Light in August on its way, William Faulkner reported for work as a screenwriter at the Culver City offices of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Bleeding from a small head wound—he said he had been struck by a cab—he announced: “I’ve got an idea for Mickey Mouse” (not, as it happened, an MGM property). Or, he suggested, he could write for newsreels; “newsreels and Mickey Mouse, these are the only pictures I like.” And then he went missing. The studio assumed he’d gone home to Mississippi, but two days later he reappeared, claiming to have been wandering in Death Valley, and commenced with the work that would occupy him—and take time away from his fiction—for much of the next dozen years.

1933 It’s almost the same name, “a mere translation of the German compound,” but for Marjorie Morgenstern, a sophomore at Hunter College sure she’s destined to become a famous actress, it’s a “white streak of revelation,” “a name that could blaze and thunder on Broadway.” “MARJORIE MORNINGSTAR,” she prints in pencil in her Hunter College biology notebook. “Marjorie Morningstar, May 7, 1933,” she tries signing in a sophisticated hand. A bestseller when it was published in 1955, Herman Wouk’s Marjorie Morningstar has had a longer life than most blockbusters, winning readers for generations even though—or perhaps because—it’s the story of Marjorie’s transformation not into Marjorie Morningstar, star of stage and screen, but into Mrs. Milton Schwartz.

1948 Orville Prescott, in the New York Times, on Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead: “Mr. Mailer is as certain to become famous as any fledgling novelist can be. Unfortunately, he is just as likely to become notorious.”

1968 After Allen Ginsberg, accompanying himself on harmonium, performed the Hare Krishna chant on Firing Line, host William F. Buckley drawled, “That’s the most unhurried Krishna I’ve ever heard.”

May 8

BORN: 1937 Thomas Pynchon (The Crying of Lot 49, Gravity’s Rainbow), Glen Cove, N.Y.

1943 Pat Barker (Regeneration, Union Street), Thornaby-on-Tees, England

DIED: 1880 Gustave Flaubert (Sentimental Education), 58, Rouen, France

2012 Maurice Sendak (Where the Wild Things Are, In the Night Kitchen), 83, Danbury, Conn.

1897 “Silly these philanderings,” Beatrice Webb wrote about her friend George Bernard Shaw. “He imagines that he gets to know women by making them in love with him. Just the contrary . . . His sensuality has all drifted into sexual vanity, delight in being the candle to the moths, with a dash of intellectual curiosity to give flavour.”

1948 As he turned up the hill from Cannery Row, a few blocks from the Pacific Biological Laboratories he had founded, Ed Ricketts was blindsided in his 1936 Buick by the evening train from San Francisco. An indefatigable marine researcher and a larger-than-life presence in Monterey, Ricketts was at the center of an intellectual and social circle that included Joseph Campbell, Henry Miller, and, most prominently, John Steinbeck, who collaborated with Ricketts on Sea of Cortez, a travelogue and research record of their expedition in the Gulf of California, and made him famous as the model for “Doc” in Cannery Row. “The greatest man in the world is dying,” Steinbeck drunkenly told a friend in New York as he waited for a flight west, “and there is nothing I can do.”

1998 “Um.” Stephen Glass hesitated. “I’m increasingly beginning to think I was duped.” On this morning, Glass and his New Republic editor, Charles Lane, were on a call with two outside reporters who thought Glass’s latest piece—on a fifteen-year-old hacker who blackmailed software companies after breaking into their databases, shouting, implausibly, “I want a Miata! I want a lifetime subscription to Playboy! Show me the money!”—was fabricated. Lane thought so too, and later that day he had Glass drive him to the building in suburban Bethesda where he claimed a “National Association of Hackers” conference had been held and where, clearly, no such thing had taken place. By the end of the day, Glass was suspended, and by the end of its investigation, the New Republic determined that at least two-thirds of the articles Glass had written for them were faked in some way.

NO YEAR Katniss Everdeen starts making dangerous bargains early in Suzanne Collins’s Hunger Games. Near-starving on her family’s scavenged diet, she can hardly wait until she reaches her twelfth birthday on this day, when she can sign up at the District 12 Justice Building for yearly credits for grain and oil for herself, her sister, and her mother. All she has to do in return: add three more slips of paper with her name on them to the big glass ball on reaping day, raising the chance she’ll be selected for the dubious privilege of representing her district in the annual Hunger Games, from which only one of twenty-four children emerges alive.

May 9

BORN: 1920 Richard Adams (Watership Down, Shardik), Newbury, England

1938 Charles Simic (The World Doesn’t End), Belgrade, Yugoslavia

DIED: 1981 Nelson Algren (The Man with the Golden Arm), 72, Sag Harbor, N.Y.

2008 Nuala O’Faolain (Are You Somebody?, My Dream of You), 68, Dublin

1931 “I was aware of the risk I was taking in opening Tanne’s letter to you,” Ingeborg Dinesen wrote to her son, Thomas, on this day. “Tanne” was her daughter, Karen, the Baroness Blixen, who was returning, reluctantly, to Denmark after the failure of her coffee farm in Kenya. The letter her mother opened was blunt—Karen would rather die than rejoin the bourgeois life she led, she declared, and she needed money from her family to begin her new life as a writer—but lovely too, with a clear-eyed sense of the beauty of the world she was leaving behind. It’s a tone she captured again in the opening of Out of Africa, written in Denmark after she took the pen name Isak Dinesen: “I had a farm in Africa, at the foot of the Ngong Hills.”

1939 Christopher Isherwood made his first visit to Washington, D.C.: “There is something charming, and even touching, about this city. For the size of the country it represents, it is absurdly small. The capital of a nation of shrewd, conservative farmers.”

1950 A year and a half before, L. Ron Hubbard had written his fellow science fiction novelist Robert Heinlein that “I will soon, I hope give you a book . . . which details in full the mathematics of the human mind, solves all the problems of the ages, and gives six recipes for aphrodisiacs and plays the mouth organ with the left foot.” And on this day Hubbard published a book that, mouth organ aside, more or less made those same claims: Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health. John W. Campbell, the editor of Astounding Science Fiction, who published an advance excerpt of the book, thought the problems of the ages had indeed been solved. “I know dianetics is one of, if not the greatest, discovery in all Man’s written and unwritten history,” he wrote one author, and predicted to another it would win Hubbard the Nobel Peace Prize.

NO YEAR Pierre Broussard may be seventy, and he may have only been a “paper shuffler” when he committed his crimes of wartime collaboration all those years ago, but his vigilance is not to be taken lightly, especially when an assassin is on his trail. T. is the second man they’ve sent to do the job: the first ended up dead at the bottom of a ravine. Brian Moore was himself past seventy when The Statement, the second-to-last novel in his varied and always interesting career, came out, and in concocting this taut philosophical thriller he proved as wily and observant as his villain, Broussard, a former Nazi collaborator who has been protected by the Church ever since the war and now finds the walls closing in around him.

May 10

BORN: 1933 Barbara Taylor Bradford (A Woman of Substance), Leeds, England

1939 Robert Darnton (The Forbidden Best-Sellers of Prerevolutionary France), New York City

DIED: 1990 Walker Percy (The Moviegoer, The Last Gentleman), 73, Covington, La.

2003 Leonard Michaels (I Would Have Saved Them if I Could), 70, Berkeley, Calif.

1849 On one side: Washington Irving and Herman Melville, who, along with forty-seven other local dignitaries, implored William Charles Macready, the noted English actor, to attempt Macbeth again and assured his safety from the nativist hooligans who drove him off the stage at the Astor Place Opera House the night before with a barrage of eggs and vegetables and cries of “Down with the English hog!” On the other side: Ned Buntline, dime novelist, street bully, and future heavy-drinking temperance activist, who roused a mob of 10,000 supporters of Macready’s rival American thespian Edwin Forrest into the theater and the surrounding streets. Macready survived the performance, but two dozen or so ruffians and bystanders were killed by soldiers shooting into what became known as the Astor Place Riot.

1907 Kenneth Grahame, banker and writer, had been telling bedtime stories about moles and water-rats to his difficult son, Alastair (known to all as “Mouse”), for a few years, but he first began to write them down in a birthday letter to Mouse, who had been dispatched with his governess on a separate holiday from his parents. Along with gifts and apologies for not being there with him, Grahame added news of the character who would soon become the center of The Wind in the Willows (and whose impulsive behavior may have been inspired by young Alastair himself): “Have you heard about the Toad? He was never taken prisoner at all.” He had stolen a motor-car and vanished “without even saying Poop-poop! . . . I fear he is a bad low animal.”

1957 Explaining she was “too well educated for the job,” Zora Neale Hurston’s supervisor fired her from her last full-time employment, as a library clerk in the space program at Patrick Air Force Base in Cocoa Beach, Florida.

2001 James Wood, in the New Republic, on J. M. Coetzee’s Disgrace: “It sometimes reads as if it were the winner of an exam whose challenge was to create the perfect specimen of a very good contemporary novel.”

2012 David Rakoff’s essays were hard to separate from his voice; many of them began, in fact, as monologues on This American Life, the radio show he contributed to from its beginnings in the mid-’90s. Along the way, he told stories of the cancer that had first struck him at age twenty-two and then returned two decades later, and in his last appearance on the show, at a live performance recorded on this day, three months before he died, Rakoff, once a dancer, with his left arm rendered useless by his tumor and surgery, danced again, alone onstage, to Nat King Cole’s “What’ll I Do?”

May 11

BORN: 1896 Mari Sandoz (Old Jules, Cheyenne Autumn), Hay Springs, Neb.

1916 Camilo José Cela (The Family of Pascual Duarte, The Hive), Padrón, Spain

DIED: 1920 William Dean Howells (A Hazard of New Fortunes), 83, New York City

1985 Chester Gould (Dick Tracy), 84, Woodstock, Ill.

1831 On May 12 New York’s Mercantile Advertiser announced a notable arrival in the city the previous day: “We understand that two magistrates, Messrs. de Beaumont and de Tonqueville, have arrived in the ship Havre, sent here by order of the Minister of the Interior, to examine the various prisons in our country, and make a report on their return to France.” The two men did indeed produce a report on American prisons after their journey through the young republic, but two years later, one of them, whose name was properly spelled Alexis de Tocqueville, published the first volume of the book that was his true purpose for the visit, Democracy in America. (In 2010, Peter Carey used the travelers’ descriptions of their arrival in New York in his novel inspired by de Tocqueville, Parrot and Olivier in America.)

1924 Drawn to a new apartment in Brooklyn Heights by his first love, a Danish sailor whose father lived in the building, Hart Crane was also attracted by another local feature: the view of the Brooklyn Bridge, “the most superb piece of construction in the modern world,” he wrote his mother on this day. “For the first time in many weeks I am beginning to further elaborate my plans for my Bridge poem.” The connection of his new home to what would become his masterwork, The Bridge, only increased when he learned that his own windows were the very ones from which Washington Roebling, invalided by an accident during the building of the support towers, had overseen by telescope the construction of the bridge he and his father had designed.

1996 The climb should have been over. At around seven the night before, Jon Krakauer had stumbled back to his tent after summiting Everest and descending through a gathering storm. But when he woke this morning he learned that one of his guides, Andy Harris, had disappeared; another, Rob Hall, was still on the summit ridge; and three or more of the climbers they had led were dead. By the end of this sunny, windy, and miserable day of searching and waiting, eight climbers were lost on the mountain—and two miraculously saved—and Krakauer was left, in despair and guilt, to sort out what went wrong in Into Thin Air.

May 12

BORN: 1812 Edward Lear (The Owl and the Pussycat, A Book of Nonsense), Holloway, England

1916 Albert Murray (The Omni-Americans, Stomping the Blues), Nokomis, Ala.

DIED: 1907 J.-K. Huysmans (Against Nature, The Damned), 59, Paris

2008 Oakley Hall (Warlock, The Downhill Racers), 87, Nevada City, Calif.

1897 Before he met Lou Andreas-Salomé, the thirty-six-year-old married intellectual who had been called by Friedrich Nietzsche—once her spurned suitor—“the smartest woman I ever knew,” at a friend’s Munich apartment on this day, René Maria Rilke, only twenty-one, had courted her with anonymous notes and poems, and after their meeting he continued his seduction with a flurry of letters. Within weeks they were lovers—she admiring his “human qualities” more than his poems—and by the fall she had convinced him to change his name from the affected-sounding René to the “beautiful, simple, and German” Rainer.

1904 Following disappointing sales for his previous two books, The House Behind the Cedars and The Marrow of Tradition, Houghton Mifflin turned down Charles W. Chesnutt’s new novel, The Colonel’s Dream, regretting that “the public has failed to respond adequately to your other admirable work in this line.” Agreeing with Houghton that “the public does not care for books in which the principal characters are colored people,” Chesnutt concentrated instead on his thriving legal stenography business, setting aside a literary career that had made him the most prominent African American novelist yet and that later generations would recognize produced some of the most incisive fiction of its era.

1948 Adventurer Apsley Cherry-Garrard, author of The Worst Journey in the World, purchased the “Aylesford copy” of a Shakespeare First Folio for £7,100.

1957 Margaret S. Libby, in the New York Herald Tribune, on Dr. Seuss’s The Cat in the Hat: “Restricting his vocabulary to a mere 223 words (all in the reading range of a six- or seven-year-old) and shortening his verse has given a certain riotous and extravagant unity, a wild restraint that is pleasing.”

1961 A fire in the Hollywood Hills destroyed the home of Aldous and Laura Huxley, sparing only a few clothes and books, a violin, the manuscript of Aldous’s Island, and, oddly, their firewood.

2009 It had been over three years since George R. R. Martin promised in a postscript to A Feast of Crows, the long-awaited and frustratingly unresolved fourth volume of his Song of Fire and Ice series, that the fifth book in the series would be done within a year, and his readers were getting restless, commenting impatiently online and creating entire websites with names like Finish the Book, George. Finally on this day his fellow author Neil Gaiman weighed in, responding to a reader who asked if Martin and fellow series authors had a responsibility to the readers waiting for their next book with the memorable phrase “George R. R. Martin is not your bitch.” In 2011, book five in the series, A Dance with Dragons, was published.

May 13

BORN: 1907 Daphne du Maurier (Rebecca, Jamaica Inn), London

1944 Armistead Maupin (Tales of the City, The Night Listener), Washington, D.C.

DIED: 1916 Sholem Aleichem (Tevye and His Daughters), 57, New York City

2001 R. K. Narayan (Malgudi Days, The English Teacher), 94, Chennai, India

1860 With Garibaldi and his Redshirts just days away from conquering Sicily for united Italy, Don Fabrizio, an aging Sicilian prince, can foresee the inevitable but is unwilling to abandon his familiar pleasures, unlike his favorite nephew, Tancredi, who joins with the Redshirts in hopes of saving the aristocracy: “If we want things to stay as they are,” he tells his uncle, “things will have to change.” Giuseppe di Lampedusa, himself a Sicilian prince, wrote The Leopard, based on the life of his grandfather, at the end of a solitary, bookish life. Rejected by publishers before his death in 1958, it became the most popular and admired Italian novel of the century, a subtle and graceful portrait of character in the middle of historical upheaval.

1871 “You will not understand at all,” Arthur Rimbaud, age sixteen, wrote his teacher and mentor George Izambard, but for a poet “the idea is to reach the unknown by the derangement of all the senses.”

1937 J. R. R. Tolkien agreed that illustrations could be added to the U.S. edition of The Hobbit, so long as they were not “from or influenced by the Disney studios (for all whose works I have a heartfelt loathing).”

1958 Unlike Hamlet’s birth, on the same day his father defeated old Fortinbras, the birth of Edgar Sawtelle on this date marked no special occasion, except the arrival of a first child to a mother and father who’d begun to think they might never have one. But the Sawtelles’ family drama soon mirrors Hamlet’s, with the suspicious death of Edgar’s father and the quick insinuation of his uncle Claude into the bed of his mother, Trudy. David Wroblewski built The Story of Edgar Sawtelle from the bones of Shakespeare’s tragedy, but he added another lineage: “the Sawtelles” refers both to Edgar’s family and to the breed of dogs they have raised, bred for a near-telepathic level of companionship that mute Edgar understands better than anyone else. And like young Fortinbras entering the scene of slaughter at Hamlet’s end, those canine Sawtelles will remain to survive the collapse of the Sawtelle line.

1961 William Maxwell, in The New Yorker, on a reissue of Francis Kilvert’s Diary: “The day-by-day record he kept is not all of equal interest; it is not above silliness; it contains sentiments that are not now acceptable (some are even shocking) and a good many ‘literary’ descriptions that don’t come off. But these are minor flaws, no journal is without them, and so long as English diaries are read, Kilvert’s humble and uneventful life will not pass altogether away.”

May 14

BORN: 1930 María Irene Fornés (And What of the Night?), Havana

1965 Eoin Colfer (Artemis Fowl), Wexford, Ireland

DIED: 1912 August Strindberg (Miss Julie, The Red Room), 63, Stockholm

1979 Jean Rhys (Wide Sargasso Sea), 88, Exeter, England

1920 Katherine Mansfield, in the Athenaeum, on Compton Mackenzie’s The Vanity Girl: “We should not waste space upon so pretentious and stupid a book were it not that we have believed in his gifts and desire to protest that he should so betray them.”

1944 For half a dozen years, Ayn Rand tried to meet with Frank Lloyd Wright to discuss the novel she was writing about an architect. “My hero is not you,” she assured him. “But his spirit is yours.” Wright proved elusive, and said he didn’t like the name “Roark” or Roark’s red hair in the sample she sent, but she forged on with the book, and in April 1944 she received a letter from Wright. “My Dear Miss Rand: I’ve read every word of The Fountainhead. Your thesis is the great one,” he wrote. “So I suppose you will be set up in the marketplace and burned as a witch.” “Thank you,” she replied on this day, but she wasn’t worried: “I think I am made of asbestos.” And then she came to the point: “Now, would you be willing to build a house for me?” (He designed one, but it was never built.)

1962 “I was cured all right”: Alex’s cheekily ironic final line in Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange matches the ending that first greeted American readers of Anthony Burgess’s novel. But the original U.K. edition (published on this day) includes an additional, more hopeful chapter in which Alex contemplates giving up the droogs and becoming a husband and father someday. That chapter was restored to all editions in the 1980s after Burgess complained that his American editor had cut it against his will, but the editor remembered otherwise; Burgess, he said, didn’t like the “Pollyanna ending” then any more than he did. The controversy was unresolved, but Burgess’s ambivalence about the ending is clear in a note written just before the final chapter on his 1961 typescript of the novel: “Should we end here? An optional ‘epilogue’ follows.”

202- Packed with characters, locations, and narrative styles, A Visit from the Goon Squad, Jennifer Egan’s prize-sweeping novel (or collection of linked stories, if you prefer), is also a book of empty spaces, the long, unnarrated stretches of time between her stories that connect them as strongly as the events she describes. In the penultimate chapter—told in PowerPoint slides—time stretches out into the 2020s, when the teenage son of Sasha Blake, the character with whom the novel began, has become obsessed with the pauses in pop songs, the one- or two-second gaps—when the song seems to be over but isn’t—that hold within their empty spaces the emotions of anticipation, release, and relief.

May 15

BORN: 1890 Katherine Anne Porter (Pale Horse, Pale Rider), Indian Creek, Tex.

1967 Laura Hillenbrand (Seabiscuit, Unbroken), Fairfax, Va.

DIED: 1886 Emily Dickinson (Poems), 55, Amherst, Mass.

1996 John Hawkes (The Beetle Leg, The Lime Twig), 72, Providence, R.I.

1853 The Reverend Arthur Nicholls, his proposal of marriage rejected by Charlotte Brontë, broke down while officiating at a public communion service. (She accepted his renewed suit the following year.)

1939 The fame of Isaac Babel in the Soviet Union and abroad could not protect him when Stalin’s secret police finally came to the door of his dacha on this morning and took him to the Lubyanka prison, where he endured six months of interrogation and was forced to write a bloodstained confession before being summoned in January to a twenty-minute nighttime trial in the private offices of Lavrenti Beria, the chief of Stalin’s secret police. He was executed in the early hours of the following morning, though his family was not told of his death until fourteen years later. “I was not given time to finish,” he was heard to say at his arrest, a plea he repeated to Beria when he made his final request, “Let me finish my work.”

1950 Mountain climbing was a different affair in those days. When Maurice Herzog and his team of French climbers set out for the Himalayas, they had no reliable map and weren’t even sure which mountain they would attempt. After weeks of exploring, they ruled out the apparently inaccessible peak of Dhaulagiri and settled on the still-mysterious Annapurna, for which Herzog set out on this morning. He returned more than a month later, having lost his toes and most of his fingers to frostbite and having become with Louis Lachenal the first to scale an 8,000-meter peak. Higher peaks have since been conquered, but Herzog’s Annapurna remains at the pinnacle of mountaineering lore.

1956 Circumstance—the discovery of a letter not meant to be sent, a mishap with a hot air balloon—can be almost as dangerous as desire in the world of Ian McEwan. In The Innocent, Leonard Marnham, a young Englishman in divided Berlin at the height of the Cold War, didn’t plan to be running around the city with two equipment cases filled with the dismembered body of the ex-husband of his German fiancée, Maria, but circumstance and desire brought him to that desperate point. And on this day they bring him to another, when, as Maria waves to him from across the airport as he leaves for London, he sees an American friend of theirs arrive unexpectedly at her side, and he makes a sudden decision that irreparably alters the rest of their lives.

1981 Valentine Cunningham, in the TLS, on Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children: “What makes it so vertiginously exciting a reading experience is the way it takes in not just the whole apple cart of India but also, and this with the unflagging zest of a Tristram Shandy, the business of being a novel at all.”

May 16

BORN: 1912 Studs Terkel (Division Street, Hard Times), New York City

1929 Adrienne Rich (Diving into the Wreck), Baltimore, Md.

DIED: 1928 Edmund Gosse (Father and Son, Gossip in a Library), 78, London

1984 Irwin Shaw (The Young Lions; Rich Man, Poor Man), 71, Davos, Switzerland

1683 Having lived alone for four and twenty years (by the reckoning of his wooden calendar) after his shipwreck off an unknown island in the Americas, Robinson Crusoe is startled by the sound of a gunshot offshore. He imagines another ship is in distress and sets a fire to signal to its survivors, but when he comes in sight of the wreck he can see there are none. Consumed by longing that one, just one, could have survived to give him a Christian companion, he salvages what he can from the ship in the following days. Shirts and fire tongs are of great use, but the bags full of gold pieces? In his isolation, they are of no more value than the dirt under his feet.

1836 On the marriage bond for his wedding to his cousin Virginia Clemm, Edgar Allan Poe and his witness, Thomas W. Cleland, attested that the bride “is of the full age of twenty-one years.” She had not yet turned fourteen.

1863 At the time, Romola, George Eliot’s fourth novel, seemed likely to mark the height of her success. She turned down £10,000 to serialize the book, “the most magnificent offer ever yet made for a novel,” but accepted a similar amount later, setting herself a double challenge: write a novel under the deadline pressure of a magazine, and set it not in present-day England, like her others, but in fifteenth-century Florence. The book was a struggle—“I began Romola as a young woman,” she said, “I finished it an old woman”—and on this day, nearing the end, she wrote in her journal about the death of her villain with understandable high spirits, “Finished Part XIII. Killed Tito in great excitement!”

1934 John Dos Passos, in the New Republic, on Robert Cantwell’s The Land of Plenty: “To tell truly, and not romantically or sentimentally, about the relation between men and machines, and to describe the machine worker, are among the most important tasks before novelists today. The job has only begun. I think Robert Cantwell is as likely to discover a method of coping with machinery, which is now the core of human life, as any man writing today.”

May 17

BORN: 1873 Dorothy Richardson (Pointed Roofs, Pilgrimage), Abington, England

1939 Gary Paulsen (Hatchet, Harris and Me), Minneapolis

DIED: 1987 Gunnar Myrdal (The American Dilemma), 88, Danderyd, Sweden

2007 Lloyd Alexander (The Black Cauldron), 83, Drexel Hill, Pa.

1824 In the drawing room of the publisher John Murray, six men committed one of literature’s most notorious acts of destruction. The body of Lord Byron, their “mad, bad, and dangerous to know” friend, was on its way back from Greece, where he had died of fever, and they were in possession of a document that could determine his legacy: his Memoirs, entrusted to his friend Tom Moore. Moore wanted them published, but after days of argument John Cam Hobhouse, Byron’s oldest friend, who hadn’t read the memoirs but feared the effect of their scandalous content on “Lord Byron’s honor & fame” (and perhaps on his own political career), won out. To Moore’s dismay that Hobhouse could destroy the book “without even opening it, as if it were a pest bag,” the pages were torn from their bindings and fed to the fire.

1890 In the Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer, a short-lived newspaper in South Dakota he largely wrote himself (and the latest in a series of failed business ventures), L. Frank Baum on this day published “Beautiful Displays of Novelties which Rival in Attractiveness the Famed Museums of the World,” an appreciation of a budding art form: the store display window. His interest in the subject didn’t end there. In 1907 he founded both The Show Window: A Journal of Practical Window Trimming for the Merchant and Professional and the National Association of Window Trimmers of America, launching a promising career he only gave up when his children’s books, beginning with Father Goose and continuing on to Oz, allowed him to devote himself to writing at the age of forty-four.

1922 Robert Littell, in the New Republic, on F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Beautiful and Damned: “Mr. Fitzgerald has a very small allowance of tenderness, and even less of pity, but for every pint of them his mixture contains gallons of blistering hatred. He hates, to be sure, just the things that I do, but it is a perilous mood to maintain.”

1928 Evelyn Waugh wrote to the TLS with a complaint: “Your reviewer refers to me throughout as ‘Miss Waugh.’ My Christian name, I know, is occasionally regarded by people of limited social experience as belonging exclusively to one or other sex; but it is unnecessary to go further into my book than the paragraph charitably placed inside the wrapper for the guidance of unleisured critics, to find my name with its correct prefix of ‘Mr.’ ”

May 18

BORN: 1048 Omar Khayyam (Rubaiyat), Nishapur, Iran

1944 W. G. Sebald (The Emigrants, The Rings of Saturn), Wertach, Germany

DIED: 1909 George Meredith (The Egoist, Modern Love), 81, Box Hill, England

2006 Gilbert Sorrentino (Mulligan Stew, Aberration of Starlight), 77, Brooklyn

1916 Though often placed on May 16, 1915—perhaps so it would fall exactly forty years to the day before James Agee’s own early death—it was on this morning that Hugh James Agee, known as Jay, driving at high speed, turned his Ford over on the Clinton Pike on his way back to Knoxville and died in the crash. His adoring son James, just six and known then as Rufus, spent much of his life putting the events of that day into words, culminating in A Death in the Family, his autobiographical novel that won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction when it was released unfinished after his own death, in which he remembered seeing his father’s body at the funeral two days later: “His face looked more remote than before and much more ordinary and it was as if he were tired or bored.”

1943 At the Lincoln University commencement ceremonies, Langston Hughes, on the stage to receive an honorary doctorate from his alma mater, “got both hungry and sleepy” as Carl Sandburg spoke on Abraham Lincoln for three and a half hours.

1945 On this afternoon, Laura Chase, age twenty-five, sharply turned the wheel of her sister’s car with her white-gloved hands and drove off the side of a Toronto bridge into the ravine below. Laura’s death, reported first by her sister, Iris, and then in the flat tones of the Toronto Star, is just the first piece in the ingeniously constructed puzzle of Margaret Atwood’s Booker Prize–winning novel, The Blind Assassin, a nest of boxes made of family and national history, science fiction, and newspaper reports that finally reveals at its center the traditional fictional engines of passion and betrayal.

2000 Was it as a gambler or a journalist that James McManus felt himself luckier when, having gone to Las Vegas to cover the World Series of Poker for Harper’s, he found himself at the final table of the WSOP’s no-limit hold-’em main event? Parlaying $4,000 the magazine hadn’t intended as a bankroll into play-in fees, McManus, a forty-year veteran of home poker games, played his way into the main event and then outlasted dozens of the game’s legends to join, among others, T. J. Cloutier, author of McManus’s instructional bible, Championship No-Limit and Pot-Limit Hold’em, at the final table. McManus’s eventual fifth-place finish (and $247,760 prize) made for the ultimate insider account, which, in Positively Fifth Street, he expanded to include the story that brought him out to Nevada in the first place, the murder of Vegas scion Ted Binion.

May 19

BORN: 1932 Elena Poniatowska (Massacre in Mexico; Here’s to You, Jesusa), Paris

1941 Nora Ephron (Heartburn, Wallflower at the Orgy), New York City

DIED: 1864 Nathaniel Hawthorne (The Blithedale Romance), 59, Plymouth, N.H.

1935 T. E. Lawrence (Seven Pillars of Wisdom, The Mint), 46, Dorset, England

1821 The Literary Gazette on Percy Bysshe Shelley’s Queen Mab: “We have spoken of Shelley’s genius, and it is doubtless of a high order; but when we look at the purposes to which it is directed, and contemplate the infernal character of all its efforts, our souls revolt with tenfold horror at the energy it exhibits, and we feel as if one of the darkest of the fiends had been clothed with a human body, to enable him to gratify his enmity against the human race, and as if the supernatural atrocity of his hate were only heightened by his power to do injury.”

1857 In a scene, recorded on this day in the Goncourt Journals, that encapsulates much of nineteenth-century French literary life, the poet Charles Baudelaire, “coming out of a tart’s rooms,” met the critic Charles-Augustin Sainte-Beauve. “Ah! I know where you’re going!” said Baudelaire. “And I know where you’ve been,” replied Sainte-Beauve. “But look,” he added, “I’d rather go and have a chat with you,” and so they retired to a café, where Sainte-Beauve declared his disgust with philosophers and their interest in the immortality of the soul, which they know “doesn’t exist any more than God does,” in an atheistic tirade so fierce, in the words of the Goncourts, “as to bring every game of dominoes in the café to a stop.”

1906 The Spectator on Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle: “This is not a book to be read for pleasure or recreation. It deals with the elementary problems of life so frankly that it can only be recommended with a grave caution, since there are scenes in it so horrible as to leave an indelible impression on the mind of the reader.”

1927 T. E. Lawrence spent the last half of his life attempting to escape his fame as “Lawrence of Arabia,” or at least manage it from a distance. Having had his cover blown when he first attempted to disappear into the ranks by enlisting in the Royal Air Force as “John Hume Ross,” he signed up again as “T. E. Shaw” and by 1927, as Revolt in the Desert, the abridged version of his memoir Seven Pillars of Wisdom, was selling tens of thousands of copies a week, he was stationed as an aircraftman second class in Karachi, overhauling engines while corresponding with Churchill, E. M. Forster, and Bernard Shaw (who may have inspired his assumed name). In one letter he explained his time abroad as “exile, endured for a specific purpose, to let the book-fuss pass over”; in another, on this day, he wrote, “I languish for my sins in publishing a little bit of the Seven Pillars called Revolt in the Desert.”

May 20

BORN: 1806 John Stuart Mill (Autobiography, On Liberty), London

1952 Walter Isaacson (Steve Jobs, Einstein, Benjamin Franklin), New Orleans

DIED: 1956 Max Beerbohm (Zuleika Dobson), 83, Rapallo, Italy

2002 Stephen Jay Gould (The Mismeasure of Man), 60, New York City

1845 “Thursday, May 20, 1845, 3-4½ p.m.” With this notation, which became his standard habit to mark their visits, Robert Browning recorded on the envelope of her most recent letter his first meeting with Elizabeth Barrett at her home—indeed, in her bedroom, for she was an invalid—on Wimpole Street. He had first written her in January in a letter that began, “I love your verses with all my heart, Miss Barrett,” but there were many barriers in the way of their meeting: her famously tyrannical father, violently skeptical of the prospect of marriage for his sickly daughter, as well as her own fear that she’d merely “make a company-show of an infirmity” for Browning and “hold a beggar’s hat for sympathy.” Meet they did, though, on this afternoon, the first of ninety visits—always with her father safely out of the house—before their elopement to Italy.

1915 E. M. Forster had chicken pox.

1953 Andrew Sean Greer’s The Story of a Marriage is not the story of the marriage that takes place on this day between Annabel DeLawn and William Platt, just before William, finally drafted, is shipped out to train for the war in Korea. The book is, instead, the story of Pearlie and Holland Cook, married a few years earlier, after Holland’s own war in the Pacific. But as Pearlie learns, no marriage—not her marriage, at least—is between just two people. In Greer’s intricate and often indirect tale, she discovers that her beautiful husband has drawn desire to him from more sources than her, and returned it too, and so she forces another couple together—Annabel and William—in the hope that her husband will then focus his desire on just one.

1990 Harry Bosch’s Sunday morning begins with a call about a body in a pipe, the body of a man he knew twenty years before. When Michael Connelly, a young crime reporter on the Los Angeles Times, introduced LAPD Detective Harry Bosch in his first novel, The Black Echo, he gave Bosch a history of high-profile cases that had made him a pariah in his own department. The body in the pipe takes him even further back, to the nightmare of his time as a “tunnel rat” in Vietnam, in a case where the strongest clues were planted years before, the last of which Bosch, fittingly, tracks down at the funeral of a fellow soldier at a veterans cemetery on Memorial Day.

NO YEAR In Fifty Shades of Grey, Christian Grey sends Ana Steele, after her final exam on Thomas Hardy, a three-volume first edition of Tess of the d’Urbervilles that must be worth a fortune.

May 21

BORN: 1688 Alexander Pope (The Rape of the Lock, The Dunciad), London

1926 Robert Creeley (For Love, Hello, Later), Arlington, Mass.

DIED: 1926 Ronald Firbank (Valmouth, The Flower Beneath the Foot), 40, Rome

2000 Barbara Cartland (The Elusive Earl, Not Love Alone), 98, Hatfield, England

1749 Writing on this day to her young lover, the marquise du Châtelet described the daily regimen she had to follow to finish her life’s work, her translation of Newton’s Principia Mathematica, by her deadline, the birth of her fourth child less than four months away: wake at eight or nine and work till three; stop for coffee and then work again from four to ten, when she dined alone and took time to talk with Voltaire, the former lover with whom she was sharing a Paris house; and then back to work from midnight to five in the morning. She did finish the book, just before she died, as she had feared, of complications from the birth of her daughter. Her book nearly perished too, but was finally published ten years later, and it remains the standard translation of Newton in France.

1813 By the time Henri Beyle rejoined Napoleon’s army at the Battle of Bautzen, the witty urban dandy was sick of war. He had survived the disastrous retreat from Russia the previous winter, and the prospect of observing more carnage, even from a comfortable distance, made him ill. “It’s like a man who has drunk too much punch and has been forced to throw it up; he is disgusted with it for life.” Of the battle, in which over 200,000 soldiers clashed and 20,000 were lost, he wrote, “We see quite well, from noon to three o’clock, everything that can be seen of a battle, which is to say, nothing,” a vision he doubtless recalled when, writing under his pen name of Stendhal two decades later, he described the chaos of Waterloo in the early pages of The Charterhouse of Parma.

1924 One of the details in “Tiny Mummies,” Tom Wolfe’s mockery of The New Yorker, that most irritated those it mocked was its gleeful furtherance of the long-standing rumor that William Shawn, The New Yorker’s editor, had as a child in Chicago been considered as a possible victim by the murderers Leopold and Loeb before they killed his classmate Bobby Franks on this day. Was it so? Wolfe claimed he saw in court records the name “William” on a list prepared by the killers, but Renata Adler, in Gone, was adamant there was no such thing, and the magazine’s most recent historian, Ben Yagoda, called the story “nonsense.” But Lillian Ross, in her memoir of her long, secret relationship with Shawn, said Shawn told her Leopold and Loeb had indeed come to his house and looked him over “as a candidate for what they were going to do.” The deeply private Shawn, of course, never said a word about it on the record.

May 22

BORN: 1859 Arthur Conan Doyle (A Study in Scarlet, The Sign of the Four), Edinburgh

1907 Hergé (Red Rackham’s Treasure, Tintin in Tibet), Etterbeek, Belgium

DIED: 1885 Victor Hugo (Les Misérables, The Hunchback of Notre Dame), 83, Paris

2010 Martin Gardner (The Ambidextrous Universe), 95, Norman, Okla.

1867 Fleeing the grasping of creditors and family, Fyodor Dostoyevsky and his new wife, Anna, embarked on a European trip funded by pawning the jewelry and silver of her dowry. Dostoyevsky held out a mad hope that he might cure their debts at the roulette table, and early in the trip he set out alone for the resort town of Bad Homburg, planning to return in just a few days. After nearly a week of losing, he wrote his wife, “If one plays coolly, calmly and with calculation, it is quite impossible to lose! I swear—it is an absolute impossibility!” (The problem, he added, was that he couldn’t keep calm.) He assured her he was leaving Homburg, though if he could just stay four more days he’d be certain to win everything back! He did stay, continued to lose, and over their next few years of travel pawned their wedding rings countless times.

1942 When Naomi Nakane sits down in 1972 to read the unsent letters her aunt Emily wrote to Naomi’s mother thirty years before, it’s like finding her “childhood house filled with rooms and corners I’ve never seen.” Written from Vancouver to Japan, where Naomi’s mother had returned to take care of their own mother before the attack on Pearl Harbor divided the countries by war, the letters begin with Emily’s wariness at the early signs that some Canadians think the Japanese families among them are enemies and end abruptly when the family packs to leave their home on this day for a tiny abandoned town in the interior, the first step in an odyssey of exclusion that lasts well beyond the war in Joy Kogawa’s novel Obasan, based in part on her own family’s history.

1944 J. R. R. Tolkien, still a decade from publishing The Lord of the Rings, mentioned to a friend that he had brought Frodo “to the very brink of Mordor,” while Gollum, he added, “continues to develop into a most intriguing character.”

1980 Children’s book editor Ursula Nordstrom confessed to her author Mary Stolz her wish she “could look EXACTLY like Dick Cavett”: “I dote on his neat, tidy spare face.”

May 23

BORN: 1810 Margaret Fuller (Woman in the Nineteenth Century), Cambridgeport, Mass.

1910 Margaret Wise Brown (Goodnight Moon, The Runaway Bunny), Brooklyn

DIED: 1906 Henrik Ibsen (Hedda Gabler, A Doll’s House), 78, Christiania, Norway

2012 Paul Fussell (The Great War and Modern Memory, Class), 88, Medford, Ore.

1948 In an “outrageously decrepit bi-motor” airplane with fifteen cases of Moose Brand Beer stowed in the canoe lashed to the plane’s belly, Farley Mowat was flown three hundred miles northwest from Churchill, Manitoba, into Canada’s northern Barrenlands with a government mission to “spend a year or two living with a bunch of wolves.” Or that’s how he tells the story of his arrival in Never Cry Wolf, one of two controversial, bestselling books, along with People of the Deer, he wrote about his first time in the barrens. The books, fierce and funny, drew attention to the mistreatment of, respectively, wolves and the local Inuit, and drew plenty of fire to Mowat, especially from the government officials with whom he engaged in spirited combat in both tales.

1980 At a garden party in Connecticut, two men met for the first time: Ian Hugo, who was married to Anaïs Nin from 1923 to her death in 1977, and Rupert Pole, who for much of that time was also married to Nin. Hugo hadn’t known about Pole, while Pole had known about Hugo but had thought their marriage was over, and for almost thirty years Nin had shuttled secretly between the two, Hugo in New York and Pole in Los Angeles. (When she died, the New York Times listed Hugo as her husband in her obituary, while the Los Angeles Times listed Pole.) Both men, of course, had accommodated other lovers of hers at times—Henry Miller not the least of them—and when Hugo died a few years after their belated meeting, it was Pole who, at Hugo’s request, scattered his ashes in Santa Monica Bay.

2003 Erich von Däniken, who was a hotel manager when he wrote Chariots of the Gods?, the improbable 1968 bestseller that argued that the wonders of ancient civilization had been left behind by extraterrestrial visitors (and that, in later editions, confidently abandoned the question mark in its original title), returned to his roots in tourism when he opened Mystery Park, a theme park in Interlaken, Switzerland, in which seven pavilions explained the evidence of ancient aliens, from Stonehenge to the Mayan calendar. Three years later, citing poor attendance, the park closed.

May 24

BORN: 1928 William Trevor (The Old Boys, Felicia’s Journey), Mitchelstown, Ireland

1963 Michael Chabon (The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay), Washington, D.C.

DIED: 1543 Nicolaus Copernicus (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres), 70, Frombork, Poland

1996 Joseph Mitchell (McSorley’s Wonderful Saloon), 87, New York City

1939 Alex Haley began a twenty-year career in uniform by enlisting in the Coast Guard.

1944 In a London car accident, Ernest Hemingway acquired a concussion and a gash in his scalp.

1945 Indicted for treason in 1943 for his support of Fascist Italy, Ezra Pound turned himself in to American authorities after the Italian surrender and on this day was driven to a makeshift prison camp in Pisa, where, for three weeks, he was held in an open cage of steel mesh before being moved to a nearby tent. Having called Hitler “a Jeanne d’Arc, a saint” after his arrest, Pound was hardly repentant, but in his captivity he wrote—first on a sheet of toilet paper in his cage and then on a typewriter he was granted as a privilege—what became known as the Pisan Cantos, ten new sections in his ongoing poetic project that reflect on his imprisonment and the lost poetic friends of his past and that contain some of his most lyrical passages, particularly the promise that “What thou lovest well remains, / the rest is dross.”

1954 “Why can’t Johnny read?” was one of the most anxious pleas of the ’50s, and in Life magazine on this day, John Hersey laid the blame on the “insipid” Dick and Jane–style primers that bored beginning readers out of their little minds. Among his solutions: bring in “wonderfully imaginative” illustrators like Dr. Seuss or Walt Disney. In response, a publisher asked Seuss to “write me a story that first-graders can’t put down,” challenging him to limit his vocabulary to 225 different words from a basic list of 348. Seuss stretched it to 236 words and came up with The Cat in the Hat, whose sales soon rivaled those of Peyton Place, although purchases by schools lagged as some considered it too unruly for classroom use.

1963 The meeting seemed to go terribly. On the invitation of Attorney General Robert Kennedy, James Baldwin brought a group including playwright Lorraine Hansberry, Lena Horne, Rip Torn, and Jerome Smith, a young activist beaten badly during the Freedom Rides, to Kennedy’s Manhattan apartment to discuss civil rights. The tension peaked when Smith said he couldn’t fight for a country that didn’t protect him from racial violence and Kennedy said if an Irish Catholic like his brother could become president blacks could too in forty years (he was off by five). Hansberry replied that if Kennedy couldn’t understand Smith’s position then “there’s no alternative to our going in the streets.” Kennedy thought he’d been ambushed, and Baldwin’s group left in despair, but later Kennedy acknowledged the meeting as a watershed in his understanding of the moral urgency of civil rights.

May 25

BORN: 1938 Raymond Carver (Will You Please Be Quiet, Please?), Clatskanie, Ore.

1949 Jamaica Kincaid (Annie John, A Small Place), St. John’s, Antigua

DIED: 1693 Madame de La Fayette (The Princess of Cleves), 59, Paris

2008 George Garrett (Death of the Fox, The Finished Man), 78, Charlottesville, Va.

1793 Twice in a week the works of William Godwin were greatly underestimated. First came Prime Minister William Pitt, who decided on this day not to prosecute Godwin for Political Justice, his lengthy and pricey radical treatise, because “a three guinea book could never do much harm among those who had not three shillings to spare.” (The book, in fact, sold well and widely in many forms and had an enormous effect on Romantic poets and radicals alike.) And then on the 31st Godwin’s friend James Marshal returned the manuscript of Godwin’s novel Caleb Williams, saying, “I should have thrust it in the fire. If you persist, the book will infallibly prove the grave of your literary fame.” The novel, in fact, was an immediate triumph, recognized then as one of the great novels of its age and now as the ingeniously constructed first “thriller.”

1900 After the Spanish-American War, William James reflected on his former student Theodore Roosevelt, “a combination of slime and grit, sand and soap” that could “scour anything away, even the moral sense of the country.”

1910 The best-known note James sent to another of his notable students, Gertrude Stein—the one that said, “Dear Miss Stein—I understand perfectly how you feel,” excusing her from the philosophy final she had abandoned in favor of a nice spring day and giving her the top grade in the class—may have been apocryphal, but the great pragmatist did write to her on this day, just months before he died. He had enjoyed the early pages of Three Lives—“This is a fine new kind of realism—Gertrude Stein is great!” he thought—but then could go no further. “You know how hard it is for me to read novels . . . As a rule reading fiction is as hard to me as trying to hit a target by hurling feathers at it. I need resistance, to cerebrate!”

1944 “I could not stand Gaudy Night,” J. R. R. Tolkien admitted to his son Christopher. “I followed P. Wimsey from his attractive beginnings so far, by which time I conceived a loathing for him (and his creatrix) not surpassed by any other character in literature known to me.”

1994 Of the many revelations in Andre Agassi’s appropriately titled memoir, Open, one of the most enjoyable (for the reader) takes us netside after a hard-fought loss to the Austrian Thomas Muster at the French Open, when Muster reached over and tousled Agassi’s hair. Or, rather, his hairpiece, which Agassi had been wearing secretly for years. “I stare at him with pure hatred,” he recalled. “Big mistake, Muster. Don’t touch the hair.” He vowed he’d never lose to “Muster the hair-musser” again, and he never did.

May 26

BORN: 1954 Alan Hollinghurst (The Folding Star, The Line of Beauty), Stroud, England

1974 Ben Schott (Schott’s Original Miscellany), London

DIED: 1976 Martin Heidegger (Being and Time), 86, Freiburg, Germany

2003 Kathleen Winsor (Forever Amber, Star Money), 83, Manhattan

1827 Edgar Allan Poe enlisted in the army under the name Edgar A. Perry.

1897 Published: Dracula by Bram Stoker (Constable, London)

1911 “Polish was being spoken nearby.” So intrudes, quietly, the presence that will soon consume the life of Gustav Aschenbach in Thomas Mann’s novella Death in Venice. Aschenbach has just arrived, lonely and aimless, at his hotel in Venice when he notices a group of young people speaking Polish, among them Tadzio, a “perfectly beautiful” boy “of perhaps fourteen,” with long curls, an opulent sailor suit, and the appearance of being pampered. Mann too once arrived in Venice (on this day) and saw a beautiful boy, who has since been traced to Władysław Moes, ten at the time (Mann was only thirty-five then, not the fifty-plus of Aschenbach) and who can be seen in a photograph on the beach in Gilbert Adair’s The Real Tadzio, his delicate features almost obscured by the gigantic bow of his beach costume.

1953 On assignment as a summertime guest college editor at Mademoiselle, Sylvia Plath interviewed Elizabeth Bowen at May Sarton’s house in Cambridge.