July Perhaps this chapter should be titled “Messidor” or “Thermidor” instead: July is the month of revolutions, and why shouldn’t a revolution sweep away the calendar as well? Along with the new metric system for weights and measures (which proved longer-lived), the French Republic introduced a new calendar that not only founded a new Year I in 1792, the first year of the Republic, but created twelve new months of three ten-day weeks each. (The five or six days left over became national holidays, les jours complémentaires, at the end of the year.) New names were given to each month by the poet Fabre d’Églantine, among them Messidor (from “harvest”) and Thermidor (from “heat”), which overlapped the traditional days of July (British wags were said to have suggested “Wheaty” and “Heaty” as local equivalents). Each day of the year had an individual name too, inspired by plants, animals, and tools: for instance, Alexandre Dumas (b. July 24, 1802), was born on Bélier (Ram), the 5th of Thermidor in Year X. Luckless Fabre d’Églantine, meanwhile, was executed for corruption by his own revolution on Laitue (Lettuce), the 16th of Germinal in Year II. (He handed out his poems on the way to the guillotine.)

America’s calendar was unaffected by its own revolution, except for the new Fourth of July celebration (which didn’t become an official federal holiday until 1870). For reading on the Fourth, along with the documents of the founders and the endless stream of biographies and histories, you can turn to Ross Lockridge Jr.’s nearly forgotten epic, Raintree County, which uses the single day of July 4, 1892, to look back on a century of American history, while George Pelecanos’s King Suckerman crackles to a final showdown at the Bicentennial celebration in Washington, D.C., and Frank Bascombe, in Richard Ford’s Independence Day (a Pulitzer winner like Raintree County), attempts a father-son reconciliation with a July Fourth weekend visit to those shrines to American male bonding, the baseball and basketball Halls of Fame. And soldier-turned-antiwar-activist Ron Kovic really was, as he titled his memoir, Born on the Fourth of July.

For a classic small-town Independence Day story of the kind that may only exist in memory and fiction, there is the tug-of-war in John D. Fitzgerald’s The Great Brain Reforms. Based on his own childhood in Utah at the turn of the last century, the eight Great Brain books embed the Tom Sawyer–like schemes of Fitzgerald’s older brother (also named Tom) in a vividly imagined community, in which the Fitzgeralds are minority “Gentiles” among Mormon settlers, and in The Great Brain Reforms, the town’s annual Fourth of July celebration, with its parade, picnic, and tug-of-war across the irrigation canal between Gentile and Mormon kids, offers yet another chance for Tom to swindle the locals, not long before he encounters a rare and temporary comeuppance that makes this fifth book the finest and most dramatic in the series.

RECOMMENDED READING FOR JULY

The Federalist Papers by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay (1788)  Anybody can have a revolution: the real achievement of the American experiment was building a system of government that could last, as argued for in these crucial essays on democracy and the balance of powers.

Anybody can have a revolution: the real achievement of the American experiment was building a system of government that could last, as argued for in these crucial essays on democracy and the balance of powers.

Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoyevsky (1866)  It’s an exceptionally hot July, and the student Raskolnikov is subject to fevers, but what is most chilling about his crimes—to him as much as anyone—is their cold-bloodedness, that they erupted from the deliberations and inexplicable resolutions of his own mind.

It’s an exceptionally hot July, and the student Raskolnikov is subject to fevers, but what is most chilling about his crimes—to him as much as anyone—is their cold-bloodedness, that they erupted from the deliberations and inexplicable resolutions of his own mind.

The Worst Journey in the World by Apsley Cherry-Garrard (1922)  No Antarctic tourist would choose the height of the southern winter for a visit, but that’s when emperor penguins nest, and so Cherry-Garrard and two companions set out on a foolhardy scientific expedition across the Ross Ice Shelf in the darkness of the Antarctic July, the “Winter Journey” that became the centerpiece of Cherry-Garrard’s classic account of the otherwise doomed Scott Expedition.

No Antarctic tourist would choose the height of the southern winter for a visit, but that’s when emperor penguins nest, and so Cherry-Garrard and two companions set out on a foolhardy scientific expedition across the Ross Ice Shelf in the darkness of the Antarctic July, the “Winter Journey” that became the centerpiece of Cherry-Garrard’s classic account of the otherwise doomed Scott Expedition.

The Killer Angels by Michael Shaara (1974)  “It rained all that night. The next day was Saturday, the Fourth of July.” Those are the final words of The Killer Angels, but there’s no danger of spoiling the story of Shaara’s Pulitzer-winning novel of Gettysburg, the battle that more than any other reclaimed the Union that had been founded four score and seven years before.

“It rained all that night. The next day was Saturday, the Fourth of July.” Those are the final words of The Killer Angels, but there’s no danger of spoiling the story of Shaara’s Pulitzer-winning novel of Gettysburg, the battle that more than any other reclaimed the Union that had been founded four score and seven years before.

Saturday Night by Susan Orlean (1990)  Orlean’s first book, a traveling celebration of the ways Americans spend their traditional night of leisure—dancing, cruising, dining out, staying in—follows no particular season, but it’s an ideal match for July, the Saturday night of months, when you are just far enough into summer to enjoy it without a care for the inevitable approach of fall.

Orlean’s first book, a traveling celebration of the ways Americans spend their traditional night of leisure—dancing, cruising, dining out, staying in—follows no particular season, but it’s an ideal match for July, the Saturday night of months, when you are just far enough into summer to enjoy it without a care for the inevitable approach of fall.

Paris Stories by Mavis Gallant (2002)  What better way to celebrate Canada Day and Bastille Day (and Independence Day too, for that matter) than with the stories of Montreal’s great expatriate writer, who left for Paris empty-handed except for the plan to make herself a writer of fiction before she was thirty, and has been publishing her stories in The New Yorker for six decades since.

What better way to celebrate Canada Day and Bastille Day (and Independence Day too, for that matter) than with the stories of Montreal’s great expatriate writer, who left for Paris empty-handed except for the plan to make herself a writer of fiction before she was thirty, and has been publishing her stories in The New Yorker for six decades since.

Call Me by Your Name by André Aciman (2007)  “This summer’s houseguest. Another bore.” Hardly: the young American academic who intruded on Elio’s family’s Italian villa set off a summer’s passion whose intensity upended his life and still sears his memory in Aciman’s elegant story of remembered, inelegant desire.

“This summer’s houseguest. Another bore.” Hardly: the young American academic who intruded on Elio’s family’s Italian villa set off a summer’s passion whose intensity upended his life and still sears his memory in Aciman’s elegant story of remembered, inelegant desire.

Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn (2012)  Five years are all it’s taken for the marriage of Amy and Nick, a once-high-flying media couple, to curdle, and Amy’s disappearance on their wedding anniversary, July 5, sets off this twisted autopsy of a marriage gone violently wrong.

Five years are all it’s taken for the marriage of Amy and Nick, a once-high-flying media couple, to curdle, and Amy’s disappearance on their wedding anniversary, July 5, sets off this twisted autopsy of a marriage gone violently wrong.

July 1

BORN: 1869 William Strunk Jr. (The Elements of Style), Cincinnati

1915 Jean Stafford (The Mountain Lion, The Collected Stories), Covina, Calif.

DIED: 1896 Harriet Beecher Stowe (Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Dred), 85, Hartford, Conn.

1983 Buckminster Fuller (Nine Chains to the Moon, Synergetics), 87, Los Angeles

1660 Samuel Pepys brought home a “fine Camlett cloak, with gold buttons, and a silk suit”: “I pray God to make me able to pay for it.”

1858 Neither author was present—Alfred Russel Wallace was specimen-hunting in Malaysia, and Charles Darwin was mourning the death of his tenth and last child—when their papers on natural selection were presented at a meeting of the Linnean Society in London on this day. Squeezed onto the program by Darwin’s friends after Wallace had surprised Darwin with an essay whose ideas matched the ones Darwin had been long developing, the papers caused little remark at the time, and the revolution they represented only began to be recognized when they were published in August, two months before Wallace, still in the jungles of Asia, learned they had been made public at all.

1916 “CECIL TEUCER VALANCE MC,” the tomb reads, with the dead man chiseled in marble in “magnificently proper” style, “FELL AT MARICOURT JULY 1 1916.” The death of Cecil Valance, the young poet taken before his time like so many in the First World War, is the event at the center of Alan Hollinghurst’s novel The Stranger’s Child, but it hardly seems to have happened at all, or at least Cecil, in all his unformed, demanding magnificence, seems hardly to have existed. His few poems will last, enough to make an industry at least, but the endless attempts to retrieve Cecil’s presence to accompany them are doomed. As one of those who loved him says gloomily ten years later, “One sees the anniversaries stretching out for ever.”

1923 Young reporter Margaret Mitchell, while interviewing Rudolf Valentino, was carried through a window by the screen star amid “gasps of admiration from a crowd of ladies.” “But,” he told her, “there are as many men that come to see me as the ladies.”

1931 There may be no other American novel that mentions money so often as James M. Cain’s Mildred Pierce. Nearly every page has a sum or a calculation, from the pennies Mildred pinches when she’s trying to get by as a single mother in the early days of the Depression to the extravagances she can’t deny herself and her monstrous daughter when their careers both take off. The book’s early chapters are haunted by the first day of July, the due date of the mortgage Mildred’s shiftless husband put on their house, which drives her to start her own pie-making business and to turn, not for the last time, to Wally, her husband’s old partner and her indifferent lover, for a loan.

1950 After banging his head docking his fishing boat in Cuba, Ernest Hemingway needed three stitches.

July 2

BORN: 1877 Hermann Hesse (Siddhartha, Steppenwolf), Calw, Germany

1919 Jean Craighead George (My Side of the Mountain), Washington, D.C.

DIED: 1904 Anton Chekhov (The Three Sisters), 44, Badenweiler, Germany

1961 Ernest Hemingway (For Whom the Bell Tolls), 61, Ketchum, Idaho

1977 Vladimir Nabokov (Pnin, Pale Fire), 78, Montreux, Switzerland

1861 Searching for the Great Comet of 1861 in the “murky” London sky, George Eliot reported she could only see the red light of a “distant gin-shop.”

1863 Told from the documents of history and from the gallant perspective of the officers whose names—Longstreet, Chamberlain, Lee, Armistead, Buford—have been tied to the Battle of Gettysburg ever since, Michael Shaara’s novel The Killer Angels has been embraced as one of the most vivid accounts of the Civil War’s turning point. The battle’s own turning point comes on this middle day, as the armies engage in their full force. “We must attack,” Lee tells Longstreet, and so they do, even though Longstreet soon finds that the Union forces he thought were on Cemetery Ridge had moved forward into the orchard below. Meanwhile, the Union’s Colonel Vincent, who won’t survive his wounds from the day, tells Chamberlain up on Little Round Top, “Looks like you’re the flank, Colonel,” which means one thing: “You must defend this place to the last.”

1925 On a summer day at a hotel in Santa Fe, Willa Cather happened on a privately published biography, The Life of the Right Reverend Joseph P. Machebeuf, by a fellow priest named Father Howlett. After reading through the night in a frenzy of inspiration, by the following day Cather had already mapped out the story of Death Comes for the Archbishop, which took the lives of Machebeuf and Jean-Baptiste Lamy as the models for its portrait of the missionary fathers Vaillant and Latour. We don’t have an exact date for Cather’s inspiration, but by early July she was already writing her friend Mabel Dodge Luhan that she was on the hunt for old priests from the area for further research, and by November Death Comes for the Archbishop was completed.

1977 On June 21, 1977, the Japanese ship Tsimtsum leaves Madras, India, for North America with a cargo of sedated zoo animals and a family of former zookeepers on board, including sixteen-year-old Pi Patel. None of them will reach their destination, though. After an explosion sinks the ship on this day, only Pi, a hyena, an orangutan, a zebra, and a Bengal tiger named Richard Parker—and soon only Pi and Richard Parker—are left to share a lifeboat, on which, if his story is to be believed, Pi and the tiger survive another 226 days before landing in Mexico. It is, admittedly, an unlikely story, but then everything about Yann Martel’s novel Life of Pi is unlikely: that the novel could actually succeed with such a preposterous premise, and that such a novel, by an unknown Canadian writer, could win the U.K.’s most prestigious literary award, the Booker Prize.

July 3

BORN: 1883 Franz Kafka (The Metamorphosis, Amerika), Prague

1937 Tom Stoppard (Arcadia, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead), Zlin, Czechoslovkia

DIED: 1904 Theodor Herzl (The Jewish State, The Old New Land), 44, Edlach, Austria

2001 Mordecai Richler (The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz), 70, Montreal

1778 After Voltaire’s death in May, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart wrote to his father: “That godless archvillain Voltaire has died like a dog, like an animal—that’s his reward!”

1910 Considering himself at age sixteen already educated beyond the capabilities of the University of Wisconsin, on his third day there Ben Hecht ran off to Chicago, where his audition as a reporter for the Chicago Daily Journal, at least as he remembered it in his lively memoir, A Child of the Century, consisted of the impromptu composition of a humorous poem about a bull that swallowed a bumblebee. Hired, he received his first introduction to the line of work he’d fondly immortalize in the play (and then film) The Front Page when his new editor, after telling him to report for work the next morning at six, answered his objection that the following day was the Fourth of July, “Allow me to contradict you, Mr. Hecht. There are no holidays in this dreadful profession you have chosen.”

1929 Edmund Wilson, in the New Republic, on D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover, nineteen years before Wilson’s own novel, Memoirs of Hecate County, was upheld as obscene by the U.S. Supreme Court: “His courageous experiment . . . should make it easier for the English writers of the future to deal more searchingly and plainly, as they are certainly destined to do, with the phenomena of sexual experience.”

1941 July 1941 was the darkest month in P. G. Wodehouse’s sunny life. Released in June from nearly a year in a German internment camp, which he described as “really great fun,” he recorded a series of radio broadcasts in Berlin with the encouragement of the Nazi authorities. They were a disaster. Bafflingly naive about his hosts and the war, which he seemed to think was one big Edwardian comedy, his comments were taken at home as signs of irresponsibility or even collaboration. Among the most furious was his fellow clubman and humorist A. A. Milne, who, long envious of Wodehouse’s more durable success, attacked him on this day for thinking politics was what “the grown-ups talk about at dinner when one is hiding under the table.” Wodehouse later got his mild revenge on Milne with his portrait of Rodney Spelvin, a hapless poet who hovered about his son’s nursery gathering material for “horribly whimsical” verses about a boy named “Timothy Bobbin.”

2006 James Wood, in the New Republic, on John Updike’s Terrorist: “Updike should have run a thousand miles away from this subject—at least as soon as he saw the results on the page.”

July 4

BORN: 1804 Nathaniel Hawthorne (The Scarlet Letter, Twice-Told Tales), Salem, Mass.

1918 Eppie Lederer (Ann Landers) and Pauline Phillips (Dear Abby), Sioux City, Iowa

DIED: 1761 Samuel Richardson (Pamela, Clarissa), 71, London

1826 Thomas Jefferson (Notes on the State of Virginia), 83, Charlottesville, Va.

1846 Charlotte Brontë submitted the Brontë sisters’ first three manuscripts (The Professor, Wuthering Heights, and Agnes Grey) to H. Colborn, beginning a year of rejection by London publishers.

1855 Published: Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman (self-published, Brooklyn)

1862 Charles Dodgson frequently took the Liddell sisters, Lorina, Edith, and Alice, on rowboat outings on the Thames, but one “golden afternoon” in July was especially remembered for the story he told the girls, in which he sent his “heroine straight down a rabbit-hole, to begin with, without the least idea what was to happen next.” Alice, the youngest, asked him to write out the adventures of her namesake, but it was another two years, during which the Liddells made a mysterious break with him that may or may not have been caused by his interest in their daughter, before he presented her with a hand-written and -illustrated pamphlet he called Alice’s Adventures Under Ground. When the story appeared in print as Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland a year later, Dodgson asked his publisher to send a copy to Alice Liddell on July 4, the anniversary of their outing.

1922 “Few people love the writings of Sir Thomas Browne,” Virginia Woolf wrote in 1923, “but those who do are the salt of the Earth.” Over the centuries the fans of Browne’s Religio Medici and Urn Burial, his 1658 meditation on fate and death provoked by the recent unearthing of ancient Roman graves, have included Dr. Johnson, Coleridge, Poe, Emerson, Melville, Joyce, Borges, and W. G. Sebald, who in The Rings of Saturn noted the odd but appropriate fact that Browne’s own bones suffered a fate entirely in keeping with his essay’s melancholy meditations about mortality: disinterred by mistake in 1840, his skull was kept on display in a Norwich hospital until on this day it was buried once again in his tomb.

1935 No American writer was more closely identified with his editor than Thomas Wolfe with Maxwell Perkins, known for wrestling Wolfe’s giant manuscripts into bestselling novels, and Wolfe grew to resent it, finally making a public break with Perkins and his publisher, Scribner’s. But when Wolfe was dying in a Seattle hospital at age thirty-seven, he reached out to his old editor, and in his final written words he fondly reminded Perkins of the Fourth of July three years before when Wolfe arrived home from Europe to find himself famous. Perkins was waiting for him at the dock, and they spent the night celebrating, capped by the dignified editor leading a climb up a fire escape to the garret in which Wolfe had written Look Homeward, Angel, and where Wolfe that night scrawled on the wall, “Thomas Wolfe lived here.”

July 5

BORN: 1958 Bill Watterson (Calvin and Hobbes), Washington, D.C.

1972 Gary Shteyngart (The Russian Debutante’s Handbook), Leningrad, USSR

DIED: 1948 Georges Bernanos (Diary of a Country Priest), 60, Neuilly-sur-Seine, France

1991 Howard Nemerov (The Winter Lightning), 71, University City, Mo.

1814 “While wading thro’ the whimsies, the puerilities, and unintelligible jargon of this work,” Thomas Jefferson wrote to John Adams after finishing Plato’s Republic for the first time, “I laid it down often to ask myself how it could have been that the world should have so long consented to give reputation to such nonsense as this?”

1911 When Lucy Maud Montgomery, whose first Anne of Green Gables books had given her financial independence at age thirty-six, finally married the minister Ewen Macdonald on this day after rejecting a number of suitors, she had a pang of ambivalence: “I felt a sudden horrible inrush of rebellion and despair,” she wrote in her journal. “I wanted to be free!” That ambivalence hasn’t prevented her uncle’s home on Prince Edward Island from becoming a shrine where hundreds of couples, mostly from Japan, where interest in “Anne of Red Hair” was strong enough to support a Canadian World theme park in the ’90s, enact their own wedding ceremonies in the same parlor where Montgomery had hers.

1922 Edmund Wilson, in the New Republic, on James Joyce’s Ulysses: “Since I have read it, the texture of other novelists seems intolerably loose and careless; when I come suddenly unawares upon a page that I have written myself I quake like a guilty thing surprised.”

1925 In Paris, Edith Wharton, though she had admired The Great Gatsby, had a disastrous tea with F. Scott Fitzgerald. Wharton was stiffly formal; Fitzgerald, thirty-four years her junior, most likely was drunk.

NO YEAR When Uncle Rondo threw a package of firecrackers into her bedroom at 6:30 in the morning, that was the last straw. They had all ganged up on her: Mama slapped her face and Papa-Daddy called her a hussy, all because Stella-Rondo came home on the Fourth of July—separated from Mr. Whitaker and with a baby named Shirley-T. she claimed was adopted—and turned them all against her. So Sister packed up the radio, the Hawaiian ukelele, and all the preserves she had put up, and headed down to the China Grove post office for good the next day, in Eudora Welty’s “Why I Live at the P.O.,” first published in the Atlantic in 1941.

1949 At a writer’s conference in Utah, Vladimir Nabokov met, and liked, Ted Geisel, Dr. Seuss, “a charming man, one of the most gifted people” there.

1974 After dreaming for three months of a “vast and important” book in his own library, Philip K. Dick tracked down the only book in his collection that matched the dream: The Shadow of Blooming Grove: Warren G. Harding in His Times, seven hundred pages long and “the dullest book in the world.”

July 6

BORN: 1946 Peter Singer (Animal Liberation, Practical Ethics), Melbourne, Australia

1952 Hilary Mantel (Wolf Hall, Bring Up the Bodies), Glossop, England

DIED: 1962 William Faulkner (Light in August; Absalom, Absalom!), 64, Byhalia, Miss.

2005 Ed McBain/Evan Hunter (The Blackboard Jungle, The Mugger), 78, Weston, Conn.

1483 “Ha! Am I king? ’Tis so. But Edward lives.” Shakespeare packed considerable drama into the nine words Richard III, perhaps his most vivid villain, speaks on taking the throne. His play, like most historians, accuses Richard of the murder of the princes Edward and Richard of Shrewsbury, his young rivals for the crown. But the boys’ disappearance remains unsolved, and Richard has had his defenders, including Josephine Tey, in whose ingenious historical mystery, The Daughter of Time, Scotland Yard inspector Alan Grant, restlessly confined to a hospital room by a broken leg, builds a case that the real Richard III, crowned on this day, was honorable, innocent, and, for that matter, not even a hunchback.

1882 Vincent van Gogh was a passionate reader, self-taught and voracious, and his letters—which are literature themselves—mention hundreds of writers and books he’d read: Hugo, Dickens, Maupassant, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Bouvard and Pecuchet. No writer is mentioned more often than Émile Zola, the French novelist (and champion of Impressionist painters), beginning with a letter to his brother, Theo, in which, in a discussion of capturing the “curious grays” of Paris at night, Van Gogh speaks of the novelist as a fellow painter: “In Une page d’amour by Émile Zola I found several townscapes painted or drawn in a masterly, masterly fashion . . . I’m very definitely going to read everything by Zola, of whom I had only known a few fragments up to now.”

1943 Philip Larkin wrote to a friend about Diana Gollancz: “I like publishers’ daughters. Oh I do like publishers’ daughters! The more we mix together, etc. I’d like to brush some of the dust off her myself.”

1945 Among those lost in a plane crash off Newfoundland on this day was Colonel Denis Capel-Dunn, returning with the British delegation from the signing of the United Nations Charter in San Francisco. Capel-Dunn rose to a high rank in wartime intelligence and might have been headed for even higher office, but instead he found another sort of notoriety nearly a half-century later when Anthony Powell, the novelist whom Capel-Dunn had hired and then quickly fired as a military secretary during the war, acknowledged that he used his former boss as a model for Kenneth Widmerpool, the “fabulous monster”—ludicrously fat, extravagantly ambitious, and ridiculously boring—who is the most memorable invention in the vast cast of characters in Powell’s twelve-volume series, A Dance to the Music of Time.

1953 Michael Straight, in the New Republic, on a new translation of Colette’s Chéri: “Colette’s preoccupation is of course with women, and she despises all of them but one.”

July 7

BORN: 1907 Robert A. Heinlein (Stranger in a Strange Land, Starship Troopers), Butler, Mo.

1933 David McCullough (Truman, John Adams), Pittsburgh

DIED: 1930 Arthur Conan Doyle (The Hound of the Baskervilles), 71, Crowborough, England

1999 Julie Campbell (Trixie Belden and the Secret of the Mansion), 91, Alexandria, N.Y.

1806 A month and a half after his first son was born, James Mill threw down a challenge to a fellow new father: “I intend to run a fair race with you in the education of a son. Let us have a well-disputed trial which of us twenty years hence can exhibit the most accomplished & virtuous young man.” (His competitiveness might be explained by the fact that the other father was William Forbes, who had married Wilhelmina Stuart, the love of Mill’s youth he was barred from marrying by his lower-class status.) If a race it was, it’s impossible to imagine that Mill didn’t win: the prodigious education of his son, John Stuart Mill—reading Greek at three and thoroughly versed in the classics by twelve, when he began assisting his father with his History of India—remains a legend in British education.

1938 In a letter full of reading advice, F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote his sixteen-year-old daughter, Scottie, “Sister Carrie, almost the first piece of American realism, is damn good and is as easy reading as a True Confession.”

NO YEAR Granner Weeks has had eighty-two birthdays before this one, but she’s still as excited as a child waiting for Santa about the party she always arranges, with flags and fireworks and cake. There used to be two parties in the same week, until she convinced her husband, Buck, to combine them. “All right by me,” he said, agreeable as always. “You won’t mind gettin your presents three days early?” “I ain’t thinking of changing my day,” she replied. “I was thinking it would be easier to change the country’s day.” Granner’s birthday party is only one of the things that bring the people of Marshboro, North Carolina—and one notable outsider—together in Jill McCorkle’s second novel, July 7th, which is set on, and named after, McCorkle’s own birthday.

2005 David Kipen, in the San Francisco Chronicle, on Jonathan Coe’s Like a Fiery Elephant: The Story of B. S. Johnson: “It’s as if Paul McCartney wrote a song about John Cage, and it made you want to listen to them both all over again.”

July 8

BORN: 1929 Shirley Ann Grau (The Keepers of the House), New Orleans

1952 Anna Quindlen (Black and Blue, One True Thing), Philadelphia

DIED: 1822 Percy Bysshe Shelley (Prometheus Unbound), 29, Gulf of Spezia, Italy

1939 Havelock Ellis (Sexual Inversion, My Life), 80, Hintlesham, England

1848 Alarmed that their novels Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights, and Agnes Grey, written under the pseudonyms of Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell, were being taken as the work of a single author, Charlotte and Anne Brontë—after failing to convince their shy sister, Emily, to join them—set out on the train for London to establish their identities to their publishers. They resisted requests, though, to announce publicly that the Bell brothers, whose violent and passionate books had caused a popular scandal, were in fact three tiny country spinsters. Meanwhile, reviews of Anne’s second novel, The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, published the same day, warned of the Bells’ “morbid love of the coarse,” a warning that may have contributed to the book’s immediate success, and to Charlotte’s suppression of the book after Anne’s death.

1940 W. H. Auden, in the New Republic, on The Wartime Letters of Rainer Maria Rilke: 1914–1921: “Now in this second and even more dreadful war, there are few writers to whom we can more profitably turn, not for comfort—he offers none—but for strength to resist the treacherous temptations that approach us disguised as righteous duties.”

1980 At eight in the morning after a sleepless and tormented night, Raymond Carver wrote a 2,000-word letter to his editor, Gordon Lish, that carries the compressed and complex emotional weight of his best stories. Surprised by the massive cuts Lish had made to the stories in his upcoming collection, What We Talk About When We Talk About Love, Carver pleaded for Lish to either reinstate the lost material or cancel the book. He was grateful to Lish for helping him become one of the most admired story writers in the country, but if the book was published as edited, he said, “I’m liable to croak.” Just two days later he wrote a conciliatory follow-up letter, and the stories were published largely as Lish had edited them, but later, in his final collection, Carver returned three of the stories to their original form.

1983 Harriett Gilbert, in the New Statesman, on Granta 8: Dirty Realism, the influential issue collecting stories by Carver, Richard Ford, Bobbie Ann Mason, Tobias Wolff, and other Americans: “This realism’s ‘dirtiness’ has little to do with decadence or ripe, organic decay. It is closer to the sadness of yesterday’s rubbish being blown down an empty street. But it also contains an element that synopsis cannot convey—a terrible edge of violence, a violence that slowly runs its thumb down the blade of each hard, tight sentence.”

July 9

BORN: 1933 Oliver Sacks (Awakenings, Uncle Tungsten), London

1951 Larry Brown (Dirty Work, Joe, Father and Son), Oxford, Miss.

DIED: 1797 Edmund Burke (Reflections on the Revolution in France), 68, Beaconsfield, England

1977 Loren Eiseley (The Immense Journey, The Firmament of Time), 69, Philadelphia

1846 “Ah Flush!, Flush!—he did not hurt you really?” Elizabeth Barrett inquired. “The truth is he hates all unpetticoated people, and though he does not hate you, he has a certain distrust of you.” The unpetticoated person in question, of course, was Miss Barrett’s suitor, Robert Browning, and Flush was her dog, the spaniel who found a further literary fame when Virginia Woolf, exhausted after finishing The Waves, amused herself by writing a “Life” of the Brownings’ dog, including a dog’s-eye retelling of this day: “At last his teeth met in the immaculate cloth of Mr. Browning’s trousers!” Flush was a popular success, but it soon lost its humor for Woolf, who called it a “silly book” about an “abominable dog.”

1875 The police surveillance of Fyodor Dostoyevsky, in place since his return from Siberian exile sixteen years before, ended.

1937 Though they were two of the prize horses in the stable of the great editor Maxwell Perkins at Scribner’s, Thomas Wolfe and F. Scott Fitzgerald had never had much to say to each other, so Wolfe was surprised to receive a letter out of the blue from Fitzgerald, although he wasn’t surprised at Fitzgerald’s advice, which he’d heard many times before: he should discipline his “unmatchable” talent by leaving more stuff out of his vast novels. Wolfe’s response, naturally, was eight times as long, but it is a marvel of disciplined and cordial dissent, claiming his place among Shakespeare, Cervantes, and Dostoyevsky, the “great putter-inners” (rather than “taker-outers”) of literature, and declaring that he was heading into the woods to do the best work of his life. (He’d be dead within the year, though, and Fitzgerald wasn’t far behind him.)

1937 “It is indeed getting more and more difficult, even pointless, for me to write in formal English,” Samuel Beckett wrote in German to Axel Kaun, a friend in Berlin, declaring he wanted to tear the language apart “in order to get to those things (or the nothingness) lying behind it.” At least in this letter he had the “consolation,” he added, “of being allowed to violate a foreign language as involuntarily as, with knowledge and intention, I would like to do against my own language, and—Deo juvante—shall do.” A decade later, Beckett abandoned his native English to write in French, beginning with Molloy, Malone Dies, and Waiting for Godot.

1961 James Dickey, in the New York Times, on Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish: “Confession is not enough, and neither is the assumption that the truth of one’s experience will emerge if only one can keep talking long enough in a whipped-up state of excitement. It takes more than this to make poetry. It just does.”

July 10

BORN: 1871 Marcel Proust (In Search of Lost Time), Auteuil, France

1931 Alice Munro (Open Secrets, The Love of a Good Woman), Wingham, Ont.

DIED: 1993 Ruth Krauss (A Hole Is to Dig, The Carrot Seed), 91, Westport, Conn.

2007 Doug Marlette (Kudzu, The Bridge), 57, Holly Springs, Miss.

1666 Less than two months before the Great Fire of London, a smaller blaze swept through Anne Bradstreet’s home in North Andover, Massachusetts, destroying her family’s library—massive for the time—of eight hundred volumes and leading her to write the “Verses upon the Burning of Our House, July 10, 1666” that bless that grace of God that “gave and took”: “It was his own it was not mine / Far be it that I should repine.”

1792 Daughter of one minister to Louis XVI and lover of another, the novelist, political theorist, and brilliant conversationalist Madame de Staël was sympathetic to the French Revolution and was no admirer of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, who despised her in return. But around this time, after her disgust at the rabble that forced their way into the Tuileries Palace in late June, she concocted a plan for the escape of the royal couple to England. She would buy an estate in Normandy, across the Channel from England, and travel there a number of times with servants who resembled the king and queen, and then make the same journey a few weeks later with the royal family disguised as the servants. Word was returned from the palace, though, that the queen, whether out of naiveté, fatalism, or distrust of her would-be rescuer, declined the offer.

1873 In the final argument of their two-year relationship, Paul Verlaine, in a drunken rage, shot Arthur Rimbaud in the arm.

1958 Jack Kerouac was the jock of the Beats, and though a broken leg derailed his football career at Columbia he kept up another sporting interest through his entire life, playing hundreds of games a year in a homemade baseball simulation of his own devising that used cards and a chart on the wall he’d throw things at to determine the plays. Even after On the Road made him one of the best-known writers of his generation, he continued to type up news reports (later archived in Kerouac at Bat) about his invented teams and players, including an issue on this day of his Baseball News that announced that young “Sugar Ray” Sims, hitting .368 in the Cuban League, had been brought up by the fourth-place St. Louis Blues to replace first baseman Joe Boston, who had broken his arm in the shower at home.

1960 Frank H. Lyell, in the New York Times, on Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird: “Movie-going readers will be able to cast most of the roles very quickly, but it is no disparagement of Miss Lee’s winning book to say that it could be the basis of an excellent film.”

July 11

BORN: 1899 E. B. White (Charlotte’s Web, Here Is New York), Mount Vernon, N.Y.

1967 Jhumpa Lahiri (Interpreter of Maladies, The Namesake), London

DIED: 1966 Delmore Schwartz (In Dreams Begin Responsibilities), 52, New York City

2012 Donald J. Sobol (Encyclopedia Brown, Boy Detective), 87, Miami, Fla.

1790 From his deathbed, Adam Smith oversaw the burning of over a dozen uncompleted volumes, including manuscripts for planned “great works” on literature and government.

1890 To the consternation of friends and family, Anton Chekhov, dissatisfied with his literary life in Moscow and looking for some kind of heroic action as he turned thirty, resolved to travel to the far eastern island of Sakhalin to inspect the penal colony there. After an arduous three-month journey—the last 3,000 miles by horse-drawn coach—he arrived in July carrying no more authority than his journalist’s credentials but soon received permission to tour the entire island, which he did, filling out over 10,000 self-designed census cards (still archived at the Russian State Library) about the prisoners, and describing their miserable conditions in an influential report, about which he wrote, “I’m glad that this rough convict’s smock will hang in my fictional wardrobe.”

1942 On this morning, three days after all books by Jewish authors were banned from sale in occupied France, Irène Némirovsky took a walk in the woods in the village of Issy-l’Évêque, where she had fled from Paris in 1940. She brought with her the second volume of Anna Karenina, the Journal of Katherine Mansfield, and an orange, and sat “in the middle of an ocean of leaves, wet and rotting from last night’s storm, as if on a raft.” That same day, she wrote her editor, “I’ve written a great deal lately. I suppose they will be posthumous books but it still makes the time go by.” Two days later she was seized by the French police and four days after that shipped in a cattle car to Auschwitz, where she died a month later, sixty years before Suite Française, the book she left unfinished, was discovered and published.

NO YEAR Everyone is in place: the glum pianist is playing Rachmaninoff, the liver lady has put her slabs of liver to sizzle in the pan, the boring couple is moving the Hoover around, the motorcycle enthusiast is clanging in the courtyard, and the staff is all ready behind the scenes for the first reenactment. After months of preparation and rehearsal, the narrator of Tom McCarthy’s Remainder can finally step out of his flat into a world “zinging with significance.” A provocative (and diabolically approachable) experiment in fiction, in which a man injured in an accident uses his legal settlement to construct a complex simulation to recreate the fleetingly intense moments of reality his unreliable memory can recall, Remainder exposes the limits and seductions of memory and the tyranny of unlimited power.

July 12

BORN: 1817 Henry David Thoreau (Walden, Civil Disobedience), Concord, Mass.

1904 Pablo Neruda (Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair), Parral, Chile

DIED: 1536 Erasmus (In Praise of Folly, On Civility in Children), 69, Basel, Switzerland

2010 Harvey Pekar (American Splendor), 70, Cleveland Heights, Ohio

1794 On the 24th day of Messidor in Year II of the French Republic (according to the new calendar proclaimed by the Revolution), Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, having been forced from his post as small-town mayor by the Jacobins, sailed for the United States, where among his most memorable adventures, recounted thirty years later in his food-lover’s classic, The Physiology of Taste, was the shooting of a wild turkey in Connecticut. While his host proclaimed the advantages of American liberty in terms that would perhaps have drawn more interest from his countryman Tocqueville, Brillat-Savarin, a man of less abstract appetites, concerned himself instead with his host’s four “buxom” daughters and with the pressing dilemma: “how best I should cook my turkey.”

1951 The army patrol had been missing in Korea for less than four days when they encountered a marine outfit near Haeju and were returned to their own unit, where they happily testified that their sergeant, Raymond Shaw, had engaged and destroyed the enemy and saved the lives of his men—minus poor Ed Malvole and Bobby Lembeck—and that, though none of them could stand Sergeant Shaw a week before, they now believed, to a man, that he was the finest, bravest, most admirable person they’d ever known. Those missing four days, of course, in Richard Condon’s delirious Cold War fantasia, The Manchurian Candidate, were spent under the expert care of Yen Lo, the brilliant Pavlovian psychologist, who left the soldiers’ brains washed almost clean—except for those nightmares Major Marco keeps having—and transformed sour, arrogant Raymond Shaw into a war hero and a programmed assassin.

1980 “Dear Madame Bonamitan, In reply to your letter of July twelfth 1980, it gives us great pleasure to inform you . . .” In reply to which letter? Sonore had written so many, on so many days, or rather Ti-Cirique, the local man of letters, had written them for her, sprinkling her appeals for work with literary quotations of woe from Hugo, Racine, and Lautréaumont. Finally this letter came in return, and with it an offer of temporary employment with the city office of urban services. But what interest had the city in her shanty neighborhood, called Texaco, a name borrowed or wrested or stolen from the oil refinery in whose shadow it arose: was it just a “pocket of insalubrity” to be cleared and cleansed? From that question grows the story of Patrick Chamoiseau’s Texaco, a full-throated and many-voiced defense of the motley Creole vigor and misery-built history of Chamoiseau’s island of Martinique.

1980 A bolt of lightning exploded Farley Mowat’s chimney on Cape Breton and showered his Volvo with shards of brick.

July 13

BORN: 1894 Isaac Babel (Red Cavalry, Odessa Tales), Odessa, Russian Empire

1934 Wole Soyinka (Ake, Death and the King’s Horseman), Abeokuta, Nigeria

DIED: 1946 Alfred Stieglitz (Camera Work), 82, New York City

1983 Gabrielle Roy (The Tin Flute, Street of Riches), 74, Quebec City

1798 The poem’s full title is “Lines written a few miles above Tintern Abbey, on revisiting the banks of the Wye during a tour, July 13, 1798,” and William Wordsworth would later say with pride that he had composed it fully in his head on a walk of four or five days with his sister, Dorothy, before writing it down. Presented as a reflection on the time since his last visit to the Wye five years before, when he was “in the hour of thoughtless youth,” it reveals, more particularly, the power and anxiety felt by someone who has just finished his first book. Lyrical Ballads, his collaboration with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, was already complete, they thought, but Wordsworth quickly inserted “Tintern Abbey” at its end, making a sort of afterword that showed he’d already outgrown the rest of his works in the collection.

1890 Vastly prolific and sourly misanthropic, Ambrose Bierce established himself as one of the best-known newspapermen on the West Coast when William Randolph Hearst hired him to write for his newly acquired San Francisco Examiner in 1887, where he contributed columns, essays, and stories, including one story, published on this day, that has likely been read more times than all his other writing combined. Anthologized and adapted almost to the point of oblivion in the years since, “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge” still packs a clean wallop, held together as it is by, in a phrase Bierce cut from the final paragraph after this first appearance of the story, “as stout a rope as ever rewarded the zeal of a civilian patriot in war-time.”

1928 Was there a real Charlie Chan? Earl Derr Biggers, who introduced the detective as a secondary character in 1925’s The House Without a Key, habitually deflected reports that Chan was modeled on an intrepid Honolulu detective named Chang Apana, but he came to embrace the idea after the two met in Hawaii. The Charlie Chan of the six books and forty-seven movies was urbane and fat, known for his fortune-cookie aphorisms, while Apana, as described in Charlie Chan, Yunte Huang’s dual biography of the man and the character, was a wiry ex-ranchhand who once wielded a five-foot bullwhip to round up a den of illegal gamblers (according to a Honolulu newspaper report on this day) and thought his English was too poor for him to accept a cameo role in the Charlie Chan movies he was offered.

July 14

BORN: 1916 Natalia Ginzburg (The City and the House), Palermo, Italy

1966 Brian Selznick (The Invention of Hugo Cabret), East Brunswick, N.J.

DIED: 1817 Germaine de Staël (Delphine; Corinne, or Italy), 51, Paris

1984 Ernest Tidyman (Shaft, Shaft’s Big Score), 56, London

1831 The governor of New York, hosting the French visitors Alexis de Tocqueville and Gustave de Beaumont, ran into his house for a gun after sighting a squirrel, but “the big man,” in Beaumont’s words, “had the clumsiness to miss him four times in succession.”

1914 F.H., in the New Republic, on Edith Wharton’s Summer: “A good shipwreck, moral or physical, is by no means the least satisfactory of fictional themes, but no author has a right to run up and down the shore line waving a harmless heroine to destruction.”

1920 In Isaac Babel’s 1920 Diary, the tersely observant record of his travels with brutal Cossack troops in the Bolshevik war against Poland that became the basis for his stories in Red Cavalry, a downed American pilot makes a single, memorable appearance, “barefoot but elegant, neck like a pillar, dazzlingly white teeth,” chatting with Babel about Bolshevism and Conan Doyle. Babel was right to suspect his name, Frank Mosher, was fake: the pilot, Captain Merian C. Cooper, had found the name written in his second-hand underwear. Meanwhile, in a fact Elif Batuman has great fun with in The Possessed, her romp through Russian literature, Captain Cooper went on to his own fame as the director of King Kong, and in the movie’s climactic scene he can be seen in the air again as the pilot of one of the planes attacking the giant ape.

1931 The “curious dismembered volume” that Henry Frobisher mentions he has discovered in a letter on this day also, winkingly, describes the novel his story is part of, David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas. “To my great annoyance,” Frobisher complains, “the pages cease, midsentence.” He’s referring to a journal written during the California gold rush by a traveler named Adam Ewing that he’s come across in the library of a Belgian château, but pages ceasing abruptly is the common affliction of five of Cloud Atlas’s six stories, which are folded inside each other like the leaves of a book, with Frobisher’s letters making up chapters two and ten and Ewing’s journal chapters one and eleven, each story linked with the next by bonds both arbitrary and meaningful.

1956 In high school in Chicago, he was the prodigy, leading his friend Saul Bellow “by the nose,” one classmate said. Among the New York intellectuals, he was, Irving Howe remembered, “our golden boy, more so than Bellow.” But Isaac Rosenfeld soon became a bohemian cautionary tale, the young man whose brilliance had taken him into a thicket of filthy basement apartments and homemade Reichian orgone boxes by the time he died at his desk of a heart attack on this day at thirty-eight.

July 15

BORN: 1892 Walter Benjamin (Illuminations, The Arcades Project), Berlin

1949 Richard Russo (Empire Falls, Straight Man), Johnstown, N.Y.

DIED: 1999 Gina Berriault (Women in Their Beds, The Son), 73, Greenbrae, Calif.

2003 Roberto Bolaño (2666, By Night in Chile, Amulet), 50, Barcelona

1677 or 1684 The illustrated adventures of Tintin take place in an abstracted geography bearing only an incomplete resemblance to our own. The intrepid boy reporter’s travels take him to countries you could once easily find on a map—Egypt, Tibet, the Soviet Union—but also to more fanciful nations like Syldavia and San Theodoros. And then there is Marlinspike Hall, the ancestral home of Sir Francis Haddock so gloriously regained by his descendant Captain Haddock at the end of Red Rackham’s Treasure. Where can it be found? For English readers, an envelope address in The Secret of the Unicorn places the mansion in England, granted to Sir Francis on this day in 1677 by Charles II. But in the original French editions, le château de Moulinsart is in Belgium, a gift on the same day in 1684 from Louis XIV. Blistering barnacles, which is to be believed?

1955 With the delivery of the mail on this day J. P. Donleavy thought his literary career was over. Included was a parcel from Paris containing two copies of his first novel, The Ginger Man, which only then did he learn his publisher, the Olympia Press, had included in their smutty “Traveller’s Companion Series” alongside such offerings as Tender Was My Flesh, School for Sin, and White Thighs. Vowing revenge, Donleavy spent the next twenty years battling with Maurice Girodias, Olympia’s publisher, over the international rights to his novel, which became more valuable every year as the notorious book became a bestseller. Finally, vengefully, Donleavy bought control of Olympia, his enemy, at a bankruptcy auction, but even then the litigation between them continued.

1988 “I can imagine you at forty,” Emma says to Dexter. “I can picture it right now.” She has the future Dexter figured out: a tiny sports car, a little paunch, a tan like a basted turkey. And he’s sure he has Emma’s number as well, as an artsy campus radical: Chagalls and manifestos on the wall, The Unbearable Lightness of Being at the side of the bed. We think we know what’s coming in the story too, after these opposites spend a night together in an Edinburgh flat, but David Nicholls has some surprises in store. In his novel One Day Nicholls revisits Emma and Dexter on July 15 every year for two decades and within that structure tells the story of their mostly parallel, sometimes passionately intersecting lives in a convincing way, by creating two people who you can imagine spend all the other days of the year thinking about each other.

1995 Amazon.com sold its first book, a copy of Douglas Hofstadter’s Fluid Concepts and Creative Analogies: Computer Models of the Fundamental Mechanisms of Thought.

July 16

BORN: 1920 Anatole Broyard (Intoxicated by My Illness, Kafka Was the Rage), New Orleans

1928 Anita Brookner (Hotel du Lac, Look at Me), London

DIED: 1995 May Sarton (Mrs. Stevens Hears the Mermaids Singing), 83, York, Maine

1995 Stephen Spender (World Within World, The Temple), 86, London

1948 With Jean Genet’s many arrests for thievery and other crimes threatening to send him to prison for life just as his novels—often veiled portraits of his life outside the law—were becoming celebrated, Jean Cocteau and Jean-Paul Sartre published an open letter on this day to French president Vincent Auriol requesting a pardon for Genet, so he could devote himself to his work. The pardon was granted, and Genet never returned to prison, but he also never wrote another novel and for a half-dozen years he wrote almost nothing at all, a fallow period perhaps caused, as his biographer Edmund White has suggested, by the unfamiliarity of his acceptance by society, which only increased with the publication in 1952 of Sartre’s massive analysis of his life and work, Saint Genet.

1951 Published: The Catcher in the Rye by J. D. Salinger (Little, Brown, Boston)

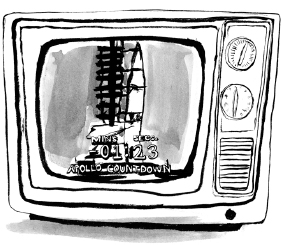

1969 John Updike had rarely encountered the present tense in fiction when he tried it out in Rabbit, Run. It felt “exhilaratingly speedy and free,” and it remained a perfect match for the Rabbit series, in which, at the end of every decade, Updike checked in on his flawed hero as he was transformed by time and by the times. In the second book, Rabbit Redux, the headlines from that turbulent era begin to invade the lives of his small-town Pennsylvania characters with a bewildering insistence, although as the novel opens, the private news that Rabbit’s father has for him—that Rabbit’s wife is having an affair—still dwarfs the event in the background on the TV, the endless replays of Apollo 11 blasting off for the moon.

July 17

BORN: 1902 Christina Stead (The Man Who Loved Children), Rockdale, Australia

1951 Mark Bowden (Black Hawk Down, Guests of the Ayatollah), St. Louis

DIED: 1790 Adam Smith (The Wealth of Nations), 67, Edinburgh

2001 Katherine Graham (Personal History), 84, Boise, Idaho

NO YEAR When Agatha Christie was challenged by a friend to try writing one of the detective stories she enjoyed so much, she began with the crime. And an ingenious one it was: in the early hours of July 17, Emily Inglethorpe, a wealthy matriarch who had just married a much younger man whom her family considered a fortune-hunting bounder, went into violent convulsions that finally killed her, an intricately planned murder whose details are revealed only when the Belgian detective Hercule Poirot, stranded nearby as a wartime refugee, is brought into the case. Written when Christie was twenty-five, The Mysterious Affair at Styles sat unread at her future publisher, the Bodley Head, for two years; finally published to superb reviews in 1921, it introduced Poirot to the world and earned its author £25.

1948 P. H. Newby, in the New Statesman and Nation, on Raymond Queneau: “To the inexperienced eye a thoroughbred racehorse looks much too thin to be healthy. One can make the same mistake over good writing. Raymond Queneau’s A Hard Winter is only half the length of an average novel, but it is twice as effective. The speed, grace and intelligence of the writing give shock after shock of pleasure.”

1960 “There’s a difference between knowing and yapping.” That’s the law of the house when the narrator of Alice Munro’s “Before the Change” returns from Toronto to stay with her father for a time. Some things—many things, nearly everything—are better off not spoken about, especially the women who come to see her father, the local doctor, in the evenings. But sometimes, to her “dismay and satisfaction,” she finds herself speaking to him of the unspoken subjects: saying the word “abortion,” for instance, or, in the last thing she tells him before his death, that she herself on July 17 had a baby and gave it away, and isn’t that ironic, given what she has finally realized about why those women come under the cover of night to see him.

1996 Everybody knew that Jack and Susan Stanton in the novel Primary Colors stood for Bill and Hillary Clinton. The question was: who was Anonymous, the secret author of one of the few political novels in memory to which the adjective “acclaimed” could legitimately be attached? Finally, six months after the book hit the bestseller lists and five months after Newsweek columnist Joe Klein heatedly denied early reports that pointed the finger at him, Klein fessed up at a press conference hastily arranged after a handwriting analysis of a manuscript of the book revealed him as the author after all, thereby bringing upon himself just the sort of temporary journalistic fury he had decried in his novel.

July 18

BORN: 1937 Hunter S. Thompson (Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas), Louisville, Ky.

1969 Elizabeth Gilbert (Eat, Pray, Love; The Last American Man), Waterbury, Conn.

DIED: 1817 Jane Austen (Emma, Northanger Abbey, Persuasion), 41, Winchester, England

1899 Horatio Alger Jr. (Ragged Dick, Luck and Pluck), 67, Natick, Mass.

1818 Writing to a friend of his disappointment that women, whom he had thought were ethereal, superior creatures, turned out to be roughly equal to men, Keats declined to say any more: “After all I do think better of Womankind than to suppose they care whether Mister John Keats five feet high likes them or not.”

1946 You’d have gotten into a fistfight with Stradlater too, if he’d come back to your room after a date and given you a hard time for writing a composition for him about how your brother Allie used to write poems on his baseball glove in green ink to give him something to read in the outfield, when you were supposed to write it about a room or a house—it was a goddam favor—and on top of that he’d just come back from a date with Jane Gallagher, who used to keep all her kings in the back row when she played you in checkers and who was the only one you’d ever shown Allie’s glove, which you kept ever since Allie died of leukemia on this day and you broke all the windows in the garage with your fist, in J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye.

2008 At first, Abdul bolted. Not far: just to the storeroom attached to his family’s shack, where he listened to the police officers arrive next door as he perched as silently as he could on the tower of garbage that, sorted for resale, represented their liquid capital. But the next morning he ran instead to the police station, to turn himself in for a crime he hadn’t committed—that no one had committed—of driving their neighbor to light herself on fire. Will Abdul get justice? It might be a central question in a different book, or a different place, but in Katherine Boo’s Behind the Beautiful Forevers, the product of three and a half years of reporting in a tiny slum neighborhood in the shadow of Mumbai’s luxury hotels and international airport, justice is an afterthought, overwhelmed by the contingencies of poverty, corruption, disease, and personality, and the rough judgments of good and bad fortune.

July 19

BORN: 1893 Vladimir Mayakovsky (The Bedbug), Baghdati, Russian Empire

1952 Jayne Anne Phillips (Machine Dreams, Lark and Termite), Buckhannon, W.Va.

DIED: 2005 Edward Bunker (Education of a Felon, Dog Eat Dog), 71, Burbank, Calif.

2009 Frank McCourt (Angela’s Ashes, Teacher Man), 78, New York City

1374 Petrarch died, bequeathing Boccaccio fifty florins to buy a dressing gown to warm him during “winter study and lucubrations by night.”

1850 After four years in Europe as a foreign correspondent for the New York Tribune, the last three of which she’d also spent aiding the democratic revolution in Rome, Margaret Fuller returned to the United States with Giovanni Angelo Ossoli, the Italian revolutionary she may have married, and their son, Nino. But in the early hours of this morning, a freak hurricane drove their ship into a sandbar off Fire Island and, while locals gathered to watch from the shore without organizing a rescue, the Ossolis drowned. Five days later, Henry David Thoreau arrived at the beach, sent by Fuller’s friend Emerson to search for any sign of their bodies or possessions, in particular the manuscript of Fuller’s book on the Roman revolution, which her admirers had hoped would have been the great work they always expected her intellect would produce.

1896 The sight of a thistle on this day, broken and dusty but still flowering on the edge of a plowed field at midsummer, evoked in Leo Tolstoy a memory of forty years before and sparked his great final story, “Hadji Murat,” at a time when he had largely abandoned fiction for philosophy. In 1852 Tolstoy had fought in the tsar’s army against Muslim Chechen guerrillas, among the most famous of whom was Hadji Murat, an admirable warrior who allied himself for a time with the Russians against a Chechen rival but then escaped, only to be killed by the Russians, his head brought back as a trophy for the decadent empire. “It stood firm,” Tolstoy wrote of the hardy thistle that reminded him of Murat, “and did not surrender to man who had destroyed all its brothers around it.”

NO YEAR “Do you mind if I marry Wilf? she asks.” She is Lydia, an actress and filmmaker, and even though she’s only marrying Wilf in a movie, Gabriel, the narrator of Michael Winter’s This All Happened and the man who has been talking about marrying her for the two years they’ve been together, does mind, enough that his jealousy evokes the strongest pang of love he’s felt all year. Gabriel began the year with two resolutions: “to decide on Lydia and to finish a novel.” The novel, we quickly realize, is the diary we’re reading, and deciding on Lydia (or waiting for Lydia to decide for him) is just one of its subjects. Set in the tiny bohemia of St. John’s, Newfoundland, This All Happened is a year’s record that conceals in its day-by-day meandering a subtle and sharp portrait of jealousy, friendship, and creative ambition.

July 20

BORN: 1924 Thomas Berger (Little Big Man, Neighbors, The Feud), Cincinnati

1933 Cormac McCarthy (Blood Meridian, The Road), Providence, R.I.

DIED: 1912 Andrew Lang (The Blue Fairy Book), 68, Banchory, Scotland

1945 Paul Valéry (La Jeune Parque, Monsieur Teste), 73, Paris

1754 Robert Louis Stevenson always said that Treasure Island began with a map he sketched to entertain his stepson. At first he called the story it inspired The Sea Cook; only when it neared publication did the book take the name of the map itself, and not until the book’s second edition did it include a woodcut of the map, which featured a detail written in its margins but not mentioned in the text of the story, “Given by above J.F. to Mr W. Bones Maste of ye Walrus Savannah this twenty July 1754 W B.” Perhaps it’s fitting that, like the treasure in the story, this lucrative creation was long fought over: for years, though Stevenson denied it, his stepson claimed that he had drawn the original map himself.

1928 With roughly 95 percent voting in favor, a local civic league in California’s San Fernando Valley officially named its town Tarzana, after the local estate of Tarzan of the Apes creator Edgar Rice Burroughs.

1945 Patrick O’Brian was both an intensely private man and a fabulist about his own history, so not until after his Aubrey-Maturin series of naval adventures had become internationally beloved was it widely revealed that he had lived the first thirty-one years of his life under a different name, Patrick Russ, legally changing his last name to O’Brian on this day, just weeks after his second marriage. Why the change? He never explained, but along with his original name he left behind a first marriage and a child, animal tales he published as a teenager, and various financial crises. Over time, with the new name, he created a new identity—Irish, Catholic, and experienced at sea—that more closely matched the stories he was writing.

1969 “The day man landed on the moon,” Philip Larkin noted, “I landed in the Nuffield,” a hospital in Hull, for the removal of a nasal polyp.

2019 Nothing dates as quickly as a vision of the future. Few writers have been as eager to look far ahead as the novelist Arthur C. Clarke, and in 1986 he assembled a book called July 20, 2019 that imagined daily human (and robot) life on the fiftieth anniversary of the moon landing. Read in retrospect as the day of its prophecy approaches, the book offers plenty of errant predictions—moon colonies, computer-controlled waterbeds, West Germany at war with the Soviet Union—although many of its other, sensibly incremental ideas are not as far from the world we know. What’s most noticeable, though, is how much Clarke’s 2019 looks like 1986: even with all the airbrushing in the world, it’s still hard to imagine oneself out of one’s own time.

July 21

BORN: 1899 Ernest Hemingway (The Sun Also Rises, A Farewell to Arms), Oak Park, Ill.

1899 Hart Crane (The Bridge, White Buildings), Garrettsville, Ohio

1966 Sarah Waters (Tipping the Velvet, Fingersmith), Neyland, Wales

DIED: 1796 Robert Burns (“A Red Red Rose,” “To a Louse”), 37, Dumfries, Scotland

1938 Owen Wister (The Virginian, Roosevelt), 78, Saunderstown, R.I.

1940 In May, H. A. Rey put aside his book illustrations so he and his wife, Margret, German Jews who had met in Brazil and returned to Paris, could begin preparing to leave France ahead of the Nazi invasion. In June, the Reys left Paris on bicycles H. A. had built from spare parts, carrying manuscripts and drawings in their baskets, including one, about a mischievous monkey, called The Adventures of Fifi. On this day they sailed from Lisbon for Rio, in October they arrived in New York, and in November they signed a contract for four books based on the work they had brought with them from France, including Fifi, which was soon renamed Curious George.

1974 On the forty-fourth and final day of Brian Clough’s disastrous reign as manager of Leeds United, the soccer club that had once been his bitterest rival, he discussed his firing on a TV panel show nearly as dramatic and unlikely as his decision, seven weeks before, to manage the club. Joining him on the panel was none other than the man he hated and had replaced: former Leeds manager Don Revie, happy to dance on Cloughie’s grave in the most polite of sporting language. It’s a scene that David Peace, in his fictional version of Cloughie’s ordeal, The Damned Utd, could hardly resist, and their tense exchange, preening and vulnerable and nearly verbatim, makes a fitting end to a novel whose propulsive and obsessive treatment of its subject has led many to call it the greatest novel on English football.

1980 “Kaufman meeting—disaster.” By the beginning of the eighties, William Goldman, Oscar-winning screenwriter of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and All the President’s Men, knew his way around Hollywood enough to sense that his first meeting with Philip Kaufman, the director of his next movie, The Right Stuff, had gone terribly. And he was right: of the 148 pages of Goldman’s script, Kaufman, more interested in the story of test pilot Chuck Yeager than in the Mercury astronauts, wanted to keep six. Who won? As Goldman wrote in Adventures in the Screen Trade, his beloved—and not unloving—memoir of Hollywood, “Whenever someone asks, ‘How much power does a screenwriter have?’ my mind goes only to those terrible days in Los Angeles. The answer, now and forever: in the crunch, none.”

2002 Craig Seligman, in the New York Times, on Adam Haslett’s You Are Not a Stranger Here: “Haslett may have talent to burn and the grades to get him into Yale, but his prose exudes a desolation so choking that it can come only from somewhere deep inside.”

July 22

BORN: 1936 Tom Robbins (Even Cowgirls Get the Blues), Blowing Rock, N.C.

1948 S. E. Hinton (The Outsiders; That Was Then, This Is Now), Tulsa, Okla.

DIED: 1990 Manuel Puig (Kiss of the Spider Woman), 57, Cuernavaca, Mexico

1996 Jessica Mitford (Hons and Rebels), 78, Oakland, Calif.

1848 John Forster, Examiner, on W. M. Thackeray’s Vanity Fair: “We are seldom permitted to enjoy the appreciation of all gentle and kind things which we continually meet within the book, without some neighbouring quip or sneer that would seem to show the author ashamed of what he yet cannot help giving way to.”

1951 This month the Oxford University Press published a natural history of the ocean by a little-known researcher at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, whose only previous book, a decade before, had earned her just $689.17 in royalties. Thanks, though, to a three-part serialization in The New Yorker and the enthusiasm of readers for her poetic approach to explaining the science of the oceans, Rachel Carson’s The Sea Around Us quickly hit the New York Times nonfiction bestseller list. This week was her second on the list, and helped by a National Book Award in January (and despite her academic publisher’s struggles to keep up with demand), she remained there for a then-record eighty-six weeks, thirty-two of them at #1.

1975 The economy’s going haywire—the prime rate yo-yoing, the cost of sugar and gas accelerating—and Ben Flesh’s body is too, ravaged by multiple sclerosis. And so the great franchiser is selling everything—his Baskin-Robbinses, his HoJos, his Western Autos—and putting all his chips in a single Travel Inn in Ringgold, Georgia, ideally situated halfway between Chicago and Disney World: two storeys, 150 rooms, opening for business on this day. Stanley Elkin’s The Franchiser is an American road novel in which all the roads, or at least the roadside attractions, look the same: trademarked golden arches, trademarked orange roofs, and trademarked turquoise towers, multiplying like the empire of Ben Flesh, who has, until now, embodied their insatiable logic of growth.

1990 Army Man, “America’s Only Magazine,” was priced at $15 for six photocopied issues mailed from the editor’s condominium in Boulder, Colorado, but it only lasted for three. On this day, George Meyer, who moved to Boulder when he soured on TV writing after stints with David Letterman and Saturday Night Live, wrote the subscribers to his homemade comedy newsletter, “I have some news for you, and I’m not going to sugar-coat it. I might varnish it . . . no, I’m not even going to varnish it. Army Man is suspending publication.” Army Man was already becoming a word-of-mouth legend, but Meyer was too busy to continue: he had been hired to write for The Simpsons along with Army Man contributors Jon Vitti and John Schwartzwelder. It was Schwartzwelder who wrote what Meyer has called “the quintessential Army Man joke: ‘They can kill the Kennedys. Why can’t they make a cup of coffee that tastes good?’ ”

July 23

BORN: 1888 Raymond Chandler (The Big Sleep; Farewell, My Lovely), Chicago

1907 Elspeth Huxley (The Flame Trees of Thika, Red Strangers), London

DIED: 2002 Chaim Potok (The Chosen, My Name Is Asher Lev), 73, Merion, Pa.

2009 E. Lynn Harris (Invisible Life, Just as I Am), 54, Los Angeles

1943 The romance of a poet dying young is difficult to resist, and Max Harris, the editor of the Australian poetry journal Angry Penguins, didn’t resist it at all when he received a packet of poems by an unknown writer named Ern Malley from someone claiming to be Malley’s sister, who said her brother had left the poems behind when he died on this day at age twenty-five. In truth, though, Malley was a product of the imaginations of James McAuley and Harold Stewart, who, fed up with the experiments of modern poetry, composed the seventeen Malley poems, which they considered nonsense, in their army barracks in a single day. Harris took the bait and devoted a special issue to announcing his discovery, and the hoax soon exploded into Australia’s greatest literary scandal, but the biggest joke of all may be that the “fake” poems of Ern Malley have outlasted those of anyone involved.

1969 Through a haze of sleeping pills, Jacqueline Susann watched Truman Capote tell Johnny Carson on The Tonight Show that she “looks like a truck driver in drag.”

1986 When he came to, on the center median of I-93 out of Boston, Andre Dubus first carefully explained to the police officer that he had three guns and was licensed to carry them. Then the pain hit. Dubus had pulled his car over to assist a woman and her brother who had just hit an abandoned motorcycle in the highway and had helped them to the median when another driver, avoiding the wreck, swerved off the highway and killed the brother and crushed Dubus’s legs. Dubus, recognized already as one of his generation’s finest short-story writers, lost one leg and the use of the other and lived in pain and depression for much of the last thirteen years of his life, but he continued to write, often about the accident and its consequences, saying more than once that having learned he had saved the woman by pushing her out of the way of the car, “Now I can never be angry at myself for stopping that night.”

July 24

BORN: 1802 Alexandre Dumas père (The Three Musketeers), Villers-Cotterêts, France

1916 John D. MacDonald (The Deep Blue Good-by), Sharon, Pa.

DIED: 1969 Witold Gombrowicz (Ferdydurke, Trans-Atlantyk), 64, Vence, France

1991 Isaac Bashevis Singer (Enemies, a Love Story; The Slave), 91, Surfside, Fla.

1895 Sigmund Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams had sold only a handful of copies when the doctor wrote to his colleague Wilhelm Fleiss, “Do you suppose that someday one will read on a marble tablet on this house: ‘Here, on July 24, 1895, the secret of the dream revealed itself to Dr. Sigm. Freud.’ So far there is little prospect of it.” Freud’s dream that fateful night, about a patient named Irma, was central to his book, where he interpreted it as an expression of his desire not to be blamed for her continuing symptoms. (Later analysts have argued Freud’s anxiety in the dream was in fact about his friend Fleiss, who had nearly killed Irma by leaving a foot and a half of gauze in her nose during an operation.) Freud’s self-fulfilling prophecy was indeed fulfilled when a marble tablet was erected at the site in 1963.

1901 William Sydney Porter, already writing stories under the name O. Henry, was released from prison after serving thirty-nine months for embezzling from his former employer, the First National Bank in Austin, Texas.

NO YEAR At a crime scene just after midnight, detectives banter until they find that the man down is one of their own, 87th Precinct detective Mike Reardon. When Evan Hunter began his 87th Precinct series with Cop Hater in 1956, making your detective a cop instead of a private eye or an elderly spinster was a new idea, as was basing a mystery series around a group of investigators (some of whom, like Detective Reardon, might die) rather than a single character. Also new was the name Hunter chose as his pseudonym for the series so there wouldn’t be any confusion with his “serious” novels like The Blackboard Jungle: Ed McBain. Hunter chose the name casually, but over time, as his 87th Precinct series grew to more than fifty police procedurals, its fame eclipsed his own.

1959 Russell Hoban was an illustrator and ad copywriter as well as a fledgling children’s book author when he submitted a picture-book manuscript called Who’s Afraid? to his editor, Ursula Nordstrom. “I’m afraid it’s going to need a lot more work, Russ,” she told him, advising him to rethink the pacing as well as the species of his young heroine, Frances: “I sort of wish any other creature but a vole which looks like a mouse. I think it is terribly difficult to draw ATTRACTIVE mice.” Over the following months both problems were solved, as Hoban reconstructed the story (and renamed it Bedtime for Frances) and illustrator Garth Williams did away with the voles: as Nordstrom informed Hoban in a later letter, “He has decided to make these people badgers.”

July 25

BORN: 1902 Eric Hoffer (The True Believer, The Passionate State of Mind), New York City

1905 Elias Canetti (Auto-da-Fé, Crowds and Power), Ruse, Bulgaria

DIED: 1834 Samuel Taylor Coleridge (Kubla Khan), 61, Highgate, England

1966 Frank O’Hara (Meditations in an Emergency), 40, Fire Island, N.Y.

1914 At age eleven, while sailing from Barcelona to New York, Anaïs Nin began her diary.

1938 When his German publishers asked about his ancestry, J. R. R. Tolkien drafted a response saying that “if I am to understand that you are enquiring whether I am of Jewish origin, I can only reply that I regret that I appear to have no ancestors of that gifted people.” He has been glad of his German name, he added, but “if impertinent and irrelevant inquiries of this sort are to become the rule in matters of literature, then the time is not far distant when a German name will no longer be a source of pride.”

1967 Invited by the Kerner Commission to contribute to its official report on the riots in Detroit that left forty-three dead and thousands of buildings destroyed, John Hersey chose instead to report from the city on his own. Soon he focused on one event: the death during the riots of three black men at the hands of white policemen. In The Algiers Motel Incident, as he had with Hiroshima two decades before, Hersey immersed himself in the lives of those present at the scene on this night, but in this book he stepped forward for the first time as a character in his own reporting. “This account is too urgent, too complex, too dangerous to too many people,” he wrote, for him to hide behind “the luxury of invisibility.”

1969 A neurologist’s medical notes took on the flavor of the fables of Sleeping Beauty or Rip Van Winkle when a group of patients in a New York hospital who had been reduced for decades to catatonic dormancy after contracting “sleeping sickness” in the ’20s were treated with a new drug, L-DOPA, that caused them, in powerfully individual ways, to awaken. With the sensitive curiosity that has since become his trademark, their young neurologist Oliver Sacks told their stories in Awakenings, including that of Rose R., who, unlike others whose awakenings held for the rest of their lives, woke fully for just a few vivid weeks that peaked on this day when, “joyous and elated, and very salacious,” she regained her lively personality, with, in Sacks’s words, an “extraordinary sense of 1926-ness,” fully immersed in the events and personalities of the year she went to sleep.

1976 On a plane in the Philippines while her husband made Apocalypse Now, Eleanor Coppola started reading volume five of the Diary of Anaïs Nin. “I almost never read. I have stopped being embarrassed about it only recently. I hardly ever watch television. I am not sure exactly how I get my information.”

July 26

BORN: 1856 George Bernard Shaw (Man and Superman, Major Barbara), Dublin

1894 Aldous Huxley (Brave New World, Crome Yellow), Godalming, England

DIED: 1934 Winsor McCay (Little Nemo in Slumberland), c. 64, Brooklyn

1957 Giuseppe di Lampedusa (The Leopard), 60, Rome