August is the only month whose name is also an adjective. But is August august? There’s nothing majestic or venerable about it. It’s sultry and lazy. It’s the height of the dog days, named after the dog star, Sirius, which was thought to reign over the hottest time of the year with a malignity that brings on lassitude, disease, and madness. “These are strange and breathless days, the dog days,” promises the opening of Tuck Everlasting, “when people are led to do things they are sure to be sorry for after.”

It’s not only the heat that can drive one mad; it’s the idleness. Without something to keep you occupied, there’s a danger your thoughts and actions will fall out of order. It was during the dog days of August when W. G. Sebald set out on a walking tour in the east of England in The Rings of Saturn, “in the hopes of dispelling the emptiness that takes hold of me whenever I have completed a long stint of work.” But he couldn’t just enjoy his freedom; he became preoccupied by it, and by the “paralyzing horror” of the “traces of destruction” his leisured observation opened his eyes to. It strikes him as no coincidence at all that exactly a year later he checked into a local hospital “in a state of almost total immobility.”

What evil can restlessness gin up in August? “Wars begin in August,” Benny Profane declares in Pynchon’s V. “In the temperate zone and twentieth century we have this tradition.” The First World War, one of the more thorough examples of modernity’s instinct for destruction, was kicked off with two shots in Sarajevo in late June, but it was only after a month of failed diplomacy that, as the title of Barbara W. Tuchman’s definitive history of the war’s beginning described them, the guns of August began to fire. “In the month of August, 1914,” she wrote, “there was something looming, inescapable, universal that involved us all. Something in that awful gulf between perfect plans and fallible men.” In some editions, The Guns of August was called August 1914, the same title Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn used for his own book on the beginning of the war, a novel about the calamitous Battle of Tannenberg that exposed the rot under the tsar and helped bring on the years of Russian revolution.

Not everyone is idle or evil in August. Many stay behind as the cities empty out in the heat, as Barbara Pym reminds us in Excellent Women, the best known of her witty and modestly willful novels of spinsters and others left out of the plots novelists usually concern themselves with. “ ‘Thank goodness some of one’s friends are unfashionable enough to be in town in August,’ ” William Caldicote says to Mildred Lathbury when he sees her on the street toward the end of the month. “ ‘No, I think there are a good many people who have to stay in London in August,’ ” she replies, “remembering the bus queues and the patient line of people moving with their trays in the great cafeteria.”

RECOMMENDED READING FOR AUGUST

Arthur Mervyn by Charles Brockden Brown (1799)  The deadly yellow fever epidemic of 1793 in Philadelphia inspired Brockden Brown’s Gothic fever dream of a novel, in which disease is but one of the anxious urban dangers threatening the young hero.

The deadly yellow fever epidemic of 1793 in Philadelphia inspired Brockden Brown’s Gothic fever dream of a novel, in which disease is but one of the anxious urban dangers threatening the young hero.

Light in August by William Faulkner (1932)  Faulkner thought he would call his tale of uncertain parentage “Dark House” until he was inspired instead by those “few days somewhere about the middle of the month when suddenly there’s a foretaste of fall” and “a luminous quality to the light” to name it instead after the month in which most of its tragedy is set.

Faulkner thought he would call his tale of uncertain parentage “Dark House” until he was inspired instead by those “few days somewhere about the middle of the month when suddenly there’s a foretaste of fall” and “a luminous quality to the light” to name it instead after the month in which most of its tragedy is set.

All the King’s Men by Robert Penn Warren (1946)  Embedded in Warren’s tale of compromises and betrayals is a summer interlude between Jack Burden and Anne Stanton, the kind of young romance during which, as Jack recalls, “even though the calendar said it was August I had not been able to believe that the summer, and the world, would ever end.”

Embedded in Warren’s tale of compromises and betrayals is a summer interlude between Jack Burden and Anne Stanton, the kind of young romance during which, as Jack recalls, “even though the calendar said it was August I had not been able to believe that the summer, and the world, would ever end.”

The Member of the Wedding by Carson McCullers (1946)  It’s the last Friday of August in that “green and crazy summer when Frankie was twelve years old,” and on Sunday her brother is going to be married. In the two days between, Frankie does her best to do a lot of growing up and, by misdirection, she does.

It’s the last Friday of August in that “green and crazy summer when Frankie was twelve years old,” and on Sunday her brother is going to be married. In the two days between, Frankie does her best to do a lot of growing up and, by misdirection, she does.

Excellent Women by Barbara Pym (1952)  It’s hard to state how thrilling it is to see the expectations and supposed rules of the novel broken so quietly and confidently: not through style or structure but through one character’s intelligent self-sufficiency, and through her creator’s willingness to pay attention to her.

It’s hard to state how thrilling it is to see the expectations and supposed rules of the novel broken so quietly and confidently: not through style or structure but through one character’s intelligent self-sufficiency, and through her creator’s willingness to pay attention to her.

The Guns of August by Barbara W. Tuchman (1962)  It only added to the aura surrounding Tuchman’s breakthrough history of the first, error-filled month of the First World War that soon after it was published John F. Kennedy gave copies of the book to his aides and told his brother Bobby, “I am not going to follow a course which will allow anyone to write a comparable book about this time [called] The Missiles of October.”

It only added to the aura surrounding Tuchman’s breakthrough history of the first, error-filled month of the First World War that soon after it was published John F. Kennedy gave copies of the book to his aides and told his brother Bobby, “I am not going to follow a course which will allow anyone to write a comparable book about this time [called] The Missiles of October.”

The Rings of Saturn by W. G. Sebald (1995)  A book—call it a memoir or a travelogue or a novel—grounded in an August walk through Suffolk, although Sebald could hardly go a sentence without being diverted by his restless curiosity into the echoes of personal and national history he heard wherever he went.

A book—call it a memoir or a travelogue or a novel—grounded in an August walk through Suffolk, although Sebald could hardly go a sentence without being diverted by his restless curiosity into the echoes of personal and national history he heard wherever he went.

Kitchen Confidential by Anthony Bourdain (2000)  In August, in a seaside village in southwest France, Bourdain tasted his first oyster, pulled straight from the ocean, and everything changed: “I’d not only survived—I’d enjoyed.”

In August, in a seaside village in southwest France, Bourdain tasted his first oyster, pulled straight from the ocean, and everything changed: “I’d not only survived—I’d enjoyed.”

August 1

BORN: 1815 Richard Henry Dana (Two Years Before the Mast), Cambridge, Mass.

1819 Herman Melville (Typee, Moby-Dick), New York City

DIED: 1743 Richard Savage (The Bastard, The Wanderer), c. 46, Bristol, England

1963 Theodore Roethke (The Lost Son, The Waking), 55, Bainbridge Island, Wash.

1866 On his forty-seventh birthday, Herman Melville played croquet. His sister, observing from a hammock, noted, “Herman was quite a hand at it.”

1928 Harold Coxe, in the New Republic, on the Mémoires de Joséphine Baker: “They are stimulating in a certain freshness and absurdity which is not often to be found, and they make you feel that, waiving prejudice, you would like Miss Baker.”

1950 “To go abroad could fracture one’s life,” V. S. Naipaul later wrote about the moment when, headed to Oxford at age seventeen, he left Trinidad and flew for the first time to New York to meet his ship to London. His attention having already turned toward the future, away from the family he wouldn’t see for another six years, he wrote his observations in a diary bought for that purpose—asking the stewardess to sharpen his pencil “to taste the luxuriousness of air travel”—but made no note then of the family farewell at the Trinidad airport nor of his first meal in New York: a roasted chicken brought from home, whose humble consumption—eaten without fork or plate over the trash basket in his hotel room, ashamed of the smell and the oil—he would nevertheless still intensely recall when he returned to his past in the autobiographical novel The Enigma of Arrival.

1956 In the hours after midnight sometime in April, Jean Shepherd, the radio host whose improvised, late-night monologues had drawn a cult audience, suggested a stunt, a prank of his fellow “Night People” against the “Day People” and their regimented lives. He sent his listeners out to ask in bookstores for a fictitious title, I, Libertine by Frederick R. Ewing, and they did in numbers enough to create a buzz in the publishing world for a book that didn’t exist. The stunt didn’t end there: as the Wall Street Journal and Village Voice reported on this day, publisher Ian Ballantine, embracing the hoax, arranged with Shepherd and novelist Theodore Sturgeon to write a book to match the title, a pastiche of eighteenth-century bawdiness that Ballantine released in the fall with a press run of 130,000 copies.

1963 Richard Chopping, commissioned to paint a toad for the original cover of Ian Fleming’s You Only Live Twice, reported back to Fleming’s editor that, “proud, do-it-yourself masochist” that he was, he had spent the previous day trudging through the swamps of Suffolk to find a suitable specimen, which now lived on mealworms under a glass dome in his studio.

August 2

BORN: 1924 James Baldwin (Notes of a Native Son, Giovanni’s Room), New York City

1942 Isabel Allende (The House of the Spirits), Lima, Peru

DIED: 1988 Raymond Carver (Cathedral, Fires), 50, Port Angeles, Wash.

1997 William S. Burroughs (The Soft Machine), 83, Lawrence, Kans.

1779 Fanny Burney’s play The Witlings seemed to amuse its audience of family and friends at its first reading, but afterward her beloved father and their close family friend Samuel Crisp, fearing scandal from its satire, wrote her what she called a “hissing, groaning, catcalling epistle,” demanding she suppress it. Burney, already celebrated as the author of the novel Evelina, was stunned—“I expected many objections to be raised—a thousand errors to be pointed out—and a million of alterations to be proposed,” she wrote her father, “but the suppression of the piece were words I did not expect”—but accepted their judgment. “I shall wipe it from my memory,” she promised bitterly, though in fact she recycled much of its plot for her next novel, Cecilia, from whose text Jane Austen soon borrowed a title phrase, Pride and Prejudice.

1805 In the first of over two hundred annual Eton-Harrow cricket matches, the longest-running rivalry in the sport, Lord Byron made 7 and 2 for the Harrow eleven. “Byron played very badly,” his captain noted; afterward, according to Byron, players from both teams made a drunken spectacle in a box at the Haymarket Theatre.

1845 Replying to his mother, who had been unhappy with a previous letter critical of the Old Testament, William Makepeace Thackeray asked: “What right have you to say I am without God because I can’t believe that God ordered Abraham to kill Isaac or that he ordered the bears to eat the little children who laughed at Elisha for being bald. You don’t believe it yourself.”

1891 Ill from tuberculosis after a lengthy trip to Africa, the African American historian George Washington Williams died in London on this day at the age of forty-one. A year before, reporting from the Congo, he had published a blistering open letter to the colony’s overseer, Leopold II of Belgium, about the “deceit, fraud, robberies, arson, murder, slave-raiding, and general policy of cruelty” of his administration, the final public act in Williams’s short but remarkable career. Though W. E. B. DuBois later remembered him as “the greatest historian of the race” and John Hope Franklin called him “one of the small heroes of the world,” Williams, whose unprecedented, thousand-page History of the Negro Race from 1619 to 1880 is one of the landmarks of African American scholarship, has largely been left out of the history that he was the first in so many cases to record.

1947 Gabriel Marcel, in the TLS, on Albert Camus’s La peste: “No doubt translations will soon appear; and then it may be that the book will be recognized as the most important which has appeared in France since the impressive novels of M. Malraux.”

August 3

BORN: 1920 P. D. James (Death in Holy Orders, The Children of Men), Oxford, England

1943 Steven Millhauser (Martin Dressler, Edwin Mullhouse), New York City

DIED: 1924 Joseph Conrad (Nostromo, Victory), 66, Bishopsbourne, England

2008 Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (The Gulag Archipelago), 89, Moscow

1890 When John Addington Symonds encountered the “Calamus” poems, with their celebration of love between men, in Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass in the 1860s, he said they “made another man of me.” For the next two decades he wrote to Whitman—and sometimes exasperated him—with his admiration, but finally on this day, with both their lives nearly over, he made his questions as explicit as he could: did Whitman agree that “those semi-sexual emotions and actions which no doubt do occur between men” were not entirely “prejudicial to social interests”? Whitman denied such “morbid inferences” should be made from his poetry and replied that the “one great difference between you and me, temperament & theory, is restraint.” He also asserted, by the way, that “tho’ always unmarried I have had six children,” a fact otherwise undocumented in his biography.

1915 Jack Burden is just a historical researcher in search of the truth, or so he tells himself while in the sullied employ of Governor Willie Stark, the charismatic despot of Robert Penn Warren’s All the King’s Men. The governor expects, correctly, that even the upstanding Judge Irwin, the hero of Jack’s youth, has a secret worthy of blackmail, and at the end of a trail across the South of old stock transactions, real estate records, and the recollections of elderly women, Jack finds it, in a letter written on this day whose plainspoken revelations cause Jack’s last illusions about the nature of men, or of one man in particular, to collapse.

1916 Harold Hannyngton Child, in the TLS, on O. Henry: “Reading him is like catching prawns with the hands. With infinite patience you close your hands over the prey, and at the very last second, when the hole for escape is all but closed, flick! the quarry has gone.”

2003 “This is America,” one immigrant chides another in Joseph O’Neill’s Netherland. “Hit the ball in the air, man.” The first immigrant is Chuck Ramkissoon, a Trinidadian whose restless, self-made schemes include the building of a quality cricket ground in the far reaches of Brooklyn; the second is Hans van den Broek, a Dutch Wall Street analyst (and middling batsman) who has been drawn into Chuck’s outer-borough world. “It’s not how I bat,” Hans protests, but on this day, in the last game of the season, he finds his free-swinging form. “I’d done it,” he thinks. “I’d hit the ball in the air like an American cricketer; and I’d done so without injury to my sense of myself.” For a moment—though it turns out to be fleeting—Hans can imagine that yes, “I am at last naturalized.”

August 4

BORN: 1961 Barack Obama (Dreams from My Father), Honolulu

1965 Dennis Lehane (A Drink Before the War, Mystic River), Boston

DIED: 1875 Hans Christian Andersen (“Thumbelina,” “The Ugly Duckling”), 70, Copenhagen

2003 James Welch (Fool’s Crow, Winter in the Blood), 62, Missoula, Mont.

1866 John Morley, in the Saturday Review, on Algernon Swinburne’s Poems and Ballads: “No language is too strong to condemn the mixed vileness and childishness of depicting the spurious passion of a putrescent imagination, the unnamed lusts of sated wantons, as if they were the crown of character and their enjoyment the great glory of human life.”

1892 Angela Carter is best known for her merrily subversive transformations of traditional European fables in books like The Bloody Chamber, but she turned the folk tales of America inside-out as well. Those legends are, of course, of a more recent vintage: the drunken lurchings of Edgar Allan Poe, the frontier dramas of Indian captivity narratives and John Ford Westerns, and, most vividly, the murders of Lizzie Borden’s father and stepmother on this day for which Borden was acquitted by a jury but convicted by popular opinion. Carter’s retelling of Lizzie’s story, “The Fall River Axe Murders,” is a fever dream of New England humidity and repression that will cause you to feel the squeeze of a corset, the jaw-clench of parsimony, and the hovering presence of the angel of death.

1913 The date of August 4 runs through the life of Florence Dowell like a line of fate, or of determination. She was born on that day, and on that day in 1901 she married John Dowell, the narrator of Ford Madox Ford’s The Good Soldier. On August 4ths in between she set off on a trip around the world and made herself the mistress of a cabin boy. And on this August 4, Florence takes a lethal dose of prussic acid and lies down, for the last time, on their hotel bed, after which her husband comes to learn the truth of the Dowells’ friendship with Edward and Leonora Ashburnham and understands that what had seemed to him “nine years of uninterrupted tranquility” were, he now assures us, “the saddest story I have ever heard.”

1947 After approaching land for the first time in ninety-seven days and nearly 4,000 nautical miles across the Pacific, Thor Heyerdahl and his Scandinavian crew spent this day maneuvering their raft Kon-Tiki to avoid a reef while offering cigarettes to the Polynesian islanders who came by canoe to investigate. Four days later they landed on another island, planting a South American coconut to symbolize Heyerdahl’s theory that South Americans on such rafts could have populated the islands, and completing an adventure tale that became a bestseller named after their raft.

1961 Orville Prescott, in the New York Times, on Robert A. Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land: a “disastrous mishmash of science fiction, laborious humor, dreary social satire, and cheap eroticism.”

August 5

BORN: 1850 Guy de Maupassant (Bel-Ami, “Boule de Suif”), Dieppe, France

1934 Wendell Berry (Jayber Crow, The Unsettling of America), Henry County, Ky.

DIED: 1895 Friedrich Engels (The Condition of the Working Class in England), 74, London

2009 Budd Schulberg (What Makes Sammy Run?), 95, Quogue, N.Y.

1920 Writing Jacob’s Room every morning, Virginia Woolf felt “each day’s work like a fence which I have to ride at, my heart in my mouth till it’s over, and I’ve cleared, or knocked the bar out.”

1925 The legend of B. Traven began with the publication in a German socialist newspaper of The Cotton-Pickers, a series of stories of proletarian life that the author claimed were drawn from his own experiences. On this day, writing to his publisher from Mexico, Traven expanded on the legend, describing the tropical torments under which he worked—“one’s bleeding hands and legs and cheeks, stung through and through by mosquitoes and other hellish insects”—while adamantly deflecting any attempts to identify himself to the public. An explosion of novels under his name in the next decade, including The Death Ship and The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, made Traven internationally known, only increasing interest in the author’s identity despite, or because of, his insistence that the work, not the man, should matter.

1944 When the motorcycle he was riding with photographer Robert Capa came under fire in France, Ernest Hemingway threw himself into a ditch and suffered a concussion on a boulder.

2006 What It Is, the title of Lynda Barry’s 2008 book, either begs or answers the question, “What is it?” What is the book itself? It’s a scrapbook and/or a memoir and/or a guidebook to creativity, and far better than any of that sounds. But, more importantly, what is “it”? Depending on the page in the book, “it” is images, or experiences, or reflection, or thoughts, or writing, or any other word we have for things that can open up a feeling of “aliveness,” that by distraction or discipline or some combination of the two allow us to pay attention to what’s around us, and to ourselves. Part personal collage, part storytelling along the lines of her old Ernie Pook’s Comeek, part activity book, What It Is is a book-long pep talk that leads by example. For instance, as she records on page 193, Lynda Barry spent this entire day drawing people dancing.

August 6

BORN: 1934 Diane di Prima (Loba, Memoirs of a Beatnik), Brooklyn

1934 Piers Anthony (A Spell for Chameleon, Split Infinity), Oxford, England

DIED: 2010 Tony Judt (Postwar, The Memory Chalet), 62, New York City

2012 Robert Hughes (The Fatal Shore, The Shock of the New), 74, Bronx, N.Y.

1666 Recently widowed but still well connected at the court of Charles II, Aphra Behn entered the king’s service as a spy. Sent to Antwerp to report on English exiles plotting against Charles after the Restoration (and to turn one of them, William Scott, an old friend, back to loyalty), she made her first report on this day, on the initial meeting between “Celladon” and “Astrea,” her code names for Scott and herself. Less than a year later she returned to London so deeply in debt she was sent to prison, after which she turned to a profession as unlikely for a woman then as espionage. As a poet, playwright, and novelist—sometimes under the same name, “Astrea”—she became, in Vita Sackville-West’s definitive phrase, “the first woman in England to earn her living by her pen.”

1945 When the great, silent flash came over the city, Miss Toshiko Sasaki was at her office desk, Dr. Masakazu Fujii and Dr. Terufumi Sasaki were in their hospitals, Mrs. Hatsuyo Nakamura was at the window in her kitchen, Father Wilhelm Kleinsorge was reading a magazine in his underwear, and the Reverend Mr. Kiyoski Tanimoto was at the doorway of a house in the suburbs. Soon after the Japanese surrender, John Hersey gathered the stories of these six survivors of the atomic blast into Hiroshima, a spare, declarative account that was given an entire issue of The New Yorker, read aloud for four straight nights on ABC radio, and sent for free to all Book-of-the-Month Club members, although the Allied occupying authorities kept it from circulating in Japan.

1989 At 9:46 in the morning on this day John Updike was still alive, and suddenly to Nicholson Baker that meant he had to write about him now. Baker had made vague plans before to examine his “obsession with Updike,” but he had thought it would be better done when his subject was dead. But now, having seen the way his thoughts about Donald Barthelme, after Barthelme’s death a few weeks before, had congealed into “sad-clown sorrowfulness” or “valedictory grand-old-man reverence,” Baker felt he had to capture his admiration for Updike while it was still anxious and dangerous, while the man and his writing were still alive. Most anxious of all, as Baker wrote in his strange and delightful book U and I, “if he dies, he won’t know how I feel about him.”

1997 The San Antonio Historic Design and Review Commission ruled that the shade of purple Sandra Cisneros had painted her house (Sherwin Williams Corsican Purple) was not historically appropriate to the King William Historic District, though, as she argued, it evoked a local history a thousand years older than the district.

August 7

BORN: 1942 Garrison Keillor (Lake Wobegon Days, WLT), Anoka, Minn.

1953 Anne Fadiman (The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down), New York City

DIED: 1941 Rabindranath Tagore (Gitanjali, The Home and the World), 80, Calcutta

1995 Brigid Brophy (Hackenfeller’s Ape, Black Ship to Hell), 66, Louth, England

1836 The “opening salvo” of New England Transcendentalism came in the form of a book of conversations with children. In 1835, Elizabeth Peabody, a teacher at the Temple School of Bronson Alcott (whose students did not yet include his daughter Louisa May), published Record of a School, composed from the open-ended dialogues of Alcott and his students. But by the time her book, and thereby his school, became acclaimed for their brilliance, their partnership had soured. The final straw for Peabody, who resigned from the school on this day, was Alcott’s next book, Conversations with Children on the Gospels, whose frank discussions of the physical basis of creation—six-year-old Josiah Quincy commented that the body was formed out of “the naughtiness of other people”—were condemned in the Boston press as “one third absurd, one third blasphemous, and one third obscene,” leading three-quarters of the school’s pupils to withdraw.

1958 There are two Chaneysville incidents in The Chaneysville Incident: one, more a part of legend than history, in which thirteen slaves, about to be captured as they made their way through southern Pennsylvania on the Underground Railroad, chose to take their own lives rather than give them up again to slavery, and a second, on this day more than a century later, when Moses Washington, a black moonshiner and a man of mysterious wealth and local power, “went hunting and came home dead.” In David Bradley’s novel, it becomes the obsessive burden of Moses’s son John, a professor of history, to return to his hometown and unearth the truth behind both incidents and the connection between them, a task that will require his scholarly skills as well as the full measure of his humanity to fulfill.

1974 It was a moment that felt lighter than air, but as substantial as the towers themselves. Two days before Nixon resigned, a man appeared in the space between the tops of Manhattan’s Twin Towers, balanced on a cable that was nearly invisible from the street below, where “the whole August morning was blown wide open, and the watchers stood rooted,” as Colum McCann describes it in Let the Great World Spin, his novel of New York stories drawn together by the man on a wire above them. From above, the man on the wire himself, Philippe Petit, had this view: “The city has changed face. Its maddening daily rush has transformed into a magnificent motionlessness. It listens. It watches. It ponders.” That’s how he remembered the moment in To Reach the Clouds, the memoir of his daring coup, which he published the year after the towers came down.

August 8

BORN: 1922 Gertrude Himmelfarb (The Roads to Modernity), Brooklyn

1931 Roger Penrose (The Road to Reality), Colchester, England

DIED: 1984 Ellen Raskin (The Westing Game), 56, New York City

2008 Ted Solotaroff (Truth Comes in Blows), 79, East Quogue, N.Y.

1920 Katherine Mansfield, in the Athenaeum, on E. M. Forster’s “Story of a Siren”: “So aware is he of his sensitiveness, of his sense of humour, that they are become two spectators who follow him wherever he goes, and are for ever on the look-out for a display of feeling.”

NO YEAR “Oh yes, I’ve no doubt in my mind that we have been invited here by a madman—probably a dangerous homicidal maniac,” Mr. Justice Wargrave remarks. Ten of them, including the judge—all strangers to each other except a married couple—have arrived for either a summer holiday or summer employment at remote Indian Island, where, by a voice on gramophone, they are charged with each having caused the death of someone in their past. And then, one by one, they begin to die. And Then There Were None (which has had nearly as many nursery-rhyme titles as it has victims) is perhaps the most intricate in Agatha Christie’s career of homicidal puzzles, a locked-room mystery that takes place on an entire island, and one, she later admitted, she was tremendously pleased to have constructed.

1969 When her friend Rex Reed decided he was too tired to go out that night, Jacqueline Susann called Sharon Tate, who had starred in the movie of her book Valley of the Dolls, and told her she wouldn’t be able to make her dinner party.

1969 The murders of seven people, including actress Sharon Tate, over two nights in the Los Angeles hills went unsolved for nearly four months, but in early 1971 Vincent Bugliosi, an L.A. prosecutor, obtained guilty verdicts against Charles Manson and three of his followers. That same year Ed Sanders, Beat poet and former member of the Fugs, writing from within the counterculture that had curdled into evil in Manson’s hands, told the story of the crimes in The Family, and in 1974 Helter Skelter, Bugliosi’s own massive, fact-heavy account of the murders and the prosecution—part Warren Report and part In Cold Blood—became a massive bestseller and one of the pop-culture tombstones marking the end of the ’60s.

August 9

BORN: 1922 Philip Larkin (“The Whitsun Weddings,” High Windows), Coventry, England

1949 Jonathan Kellerman (When the Bough Breaks), New York City

DIED: 1967 Joe Orton (Entertaining Mr. Sloane, Loot), 34, London

2008 Mahmoud Darwish (Unfortunately, It Was Paradise), 67, Houston, Tex.

1853 From the seaside, George Eliot wrote that the “sacraments” of swimming and beer-drinking have been “very efficacious.”

1912 “Will you stand by me in a crisis?” P. G. Wodehouse wrote apologetically to Arthur Conan Doyle. “A New York lady journalist, a friend of mine, is over here gunning for you. She said ‘You know Conan Doyle, don’t you?’ I said, ‘I do. It is my only claim to fame’. She then insisted on my taking her to see you . . . Can you stand this invasion? If so, we will arrive in the afternoon.”

1925 “You are right about Gatsby being blurred and patchy,” F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote to John Peale Bishop. “I never at any one time saw him clear myself—for he started as one man I knew and then changed into myself—the amalgam was never complete in my mind.”

1945 “Did I tell you what Jean-Paul Sartre said about your work? He’s a little man with bad teeth, absolutely the best talker I ever met,” Malcolm Cowley wrote to William Faulkner. “Pour les jeunes en France, Faulkner c’est un dieu.” Faulkner, mired in Hollywood with his books out of print, could hardly have minded being called a god, nor did he resist Cowley’s pitch in the same letter to construct a Portable Faulkner, a one-volume anthology that would introduce his writing as an interconnected Mississippi saga and also give a “bayonet prick in the ass of Random House to reprint” his books. Faulkner agreed—“By all means let us make a Golden Book of my apocryphal county”—and The Portable Faulkner, published to great success in 1946, followed by Faulkner’s Nobel Prize in 1949, cemented his reputation as, indeed, a god among American novelists.

1984 Walter Tevis, who described himself as a “good American writer of the second rank,” died on this day at the age of fifty-six, with his novels obscured by the glare of the movies a few of them had become, by his cussed indifference to keeping to a single genre of storytelling, and perhaps by his own blunt self-effacement. His promising first novel, The Hustler, became a hit movie with Paul Newman and Jackie Gleason. His second, The Man Who Fell to Earth, confounded expectations with its switch to science fiction but became the source for David Bowie’s most vivid screen role. Tevis then spent seventeen years mostly teaching and drinking, but in his last years he turned again to writing and published a flurry of books, including the Hustler sequel, The Color of Money, and two novels, The Queen’s Gambit and Mockingbird, that have developed devoted followings without the benefit, or curse, of a movie adaptation.

August 10

BORN: 1962 Suzanne Collins (The Hunger Games, Catching Fire), Hartford, Conn.

1963 Andrew Sullivan (Virtually Normal), South Godstone, England

DIED: 1948 Montague Summers (The History of Witchcraft and Demonology), 68, Richmond, England

1914 In early August, as the European powers gathered themselves for battle, two speedy German ships of war, the Goeben and the Breslau, were pursued east across the Mediterranean by a fleet of British cruisers that exchanged fire with the Germans but couldn’t prevent their escape to the waters of their new Turkish ally. As Barbara W. Tuchman mentioned in The Guns of August, “the daughter, son-in-law, and three grandchildren of the American ambassador Mr. Henry Morgenthau” observed the gunfire from a “small Italian passenger steamer,” and Morgenthau’s daughter gave an account of the confrontation to the German and Austrian ambassadors in Constantinople on this day. What Tuchman didn’t mention is that the eyewitness was her own mother, and that the “three grandchildren” on the steamer were her sisters, Josephine and Anne, and herself, age two.

1945 Graham Greene, in the Evening Standard, on George Orwell’s Animal Farm: “If Mr Walt Disney is looking for a real subject, here it is: it has all the necessary humour, and it has, too, the subdued lyrical quality he can sometimes express so well. But it is perhaps a little too real for him?”

1958 Glenn Gould was not averse to placing his idiosyncratically brilliant piano career in a literary context, as in a self-interview he conducted in which he suggested to himself that the Salzburg Festspielhaus, where he played a concert on this day, would, with its “Kafka-like setting at the base of a cliff,” be a perfect site for “the martyr’s end you so desire.” And others have been equally willing to use him as a character, most memorably in Thomas Bernhard’s novel, The Loser, the story of two gifted piano students driven to give up the instrument (and in one case to suicide) by the greater talent of their fellow student Gould. Bernhard plays loose with the details of Gould’s life, but he too mentions a Salzburg concert and imagines, as Gould did, a sort of martyrdom to music: in his story Gould dies of a stroke, not while sleeping as in real life, but while playing the Goldberg Variations.

1967 Among Kurt Vonnegut’s advice to a friend coming to teach at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop: “Go to all the football games,” “Cancel classes whenever you damn please,” and “Don’t ball undergraduates. Their parents are still watching.”

2012 Contemplating retirement after fifty-five years as a book dealer and hoping to “seed the clouds” of the used-book market, Larry McMurtry opened Booked Up, his four-building store in his hometown of Archer City, Texas, to what he called, in a nod to one of his early novels, the Last Book Sale, selling off two-thirds of his 400,000-book stock by auction.

August 11

BORN: 1897 Louise Bogan (The Blue Estuaries), Livermore Falls, Maine

1922 Mavis Gallant (From the Fifteenth District), Montreal

DIED: 1890 John Henry Newman (Apologia pro vita sua), 89, Edgbaston, England

1979 J. G. Farrell (Troubles, The Siege of Krishnapur), 44, Bantry Bay, Ireland

NO YEAR Ever since the strange wreck of a ship nearby, with no apparent survivors save an immense dog that bounded out of sight, the beautiful Lucy Westenra has had restless nights, and in the early, dark hours of August 11 her dear friend Mena wakes to discover Lucy’s bed empty and Lucy nowhere to be found. Searching for her out on the cliffs, Mena sees in the ruined abbey across the harbor something dark bending over a white figure, but when she reaches the abbey Lucy is alone and sleeping. All seems well the next morning, in the best-known novel by Irish theatrical manager Bram Stoker, Dracula, except for those two pinpricks on Lucy’s neck, which Mena must have caused when she clumsily used a safety pin to wrap a shawl around her in the night.

1937 When Max Eastman wrote in “Bull in the Afternoon,” his lengthy takedown of his old friend Ernest Hemingway’s Death in the Afternoon in the New Republic in 1933, “that Hemingway lacks the serene confidence that he is a full-sized man,” and compared his literary style to “wearing false hair on the chest,” it was, well, like waving a red flag in front of his subject. Hemingway fumed and wrote public letters asserting his “potency,” and four years later, when he found Eastman in his editor Maxwell Perkins’s office, he pulled open his shirt to reveal his full, authentic pelt. Before long the two men were grappling on the floor. They continued their battle for days in the New York papers, with Eastman claiming he had stood the younger man on his head while Hemingway offered a rematch: for $1,000, they would be left alone in a room and “the best man unlocks the door.”

1994 There may never have been a more inspired pairing of book reviewer and subject than when the New York Review of Books commissioned Nicholson Baker to review volume one (A–G) of the Historical Dictionary of American Slang, edited by J. H. Lighter. Baker, the author of both the micro-epics The Mezzanine and Room Temperature and the highbrow smut of Vox and, later, House of Holes, was like a pig in, uh, slop, celebrating the way the reference book made worn lingo like “broke-dick” and “dingleberry” freshly funny again—thanks in part to the recurring, deadpan punch line “(usu. considered vulgar)”—and constructing a homemade grid charting the various combinations of prefixes (cheese-, dirt-, scum-) and suffixes (-ball!, -bag!, -wad!) that the ingenuity of human insult had, so far, concocted.

August 12

BORN: 1937 Walter Dean Myers (Fallen Angels, Monster), Martinsburg, W.Va.

1964 Katherine Boo (Behind the Beautiful Forevers), Washington, D.C.

DIED: 1955 Thomas Mann (The Magic Mountain, Doctor Faustus), 80, Zurich

1964 Ian Fleming (Dr. No, Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang), 56, Canterbury, England

1803 With Napoleon’s armies massing on the other side of the English Channel, Britain hastily deployed troops in the towns along the coast, including Felpham, the tiny Sussex village where William Blake had moved a few years before, and where he had an altercation with a Private Schofield that nearly cost him his freedom. The soldier claimed Blake had shouted words of sedition, “Damn the King. The soldiers are all slaves,” and that Blake’s wife added that she would fight for Napoleon “as long as I am able.” Blake was no admirer of the king, but he was quickly acquitted at trial when no witnesses would support the soldier. In his later poetry, he would celebrate “sweet Felpham,” and forever curse “Skofield” as a “minister of evil.”

1967 It is nearly impossible to think of Scott Spencer’s third novel without being reminded of the young Brooke Shields or without hearing Diana Ross and Lionel Richie breathe its title, Endless Love, in your mind’s ear, but behind that gauzy scrim there’s a novel that engages directly with the kind of overwhelming teen passion usually left to pop songwriters. The story begins with a fire, a small flame that David Axelrod lights on the porch of the girl—and the entire family—he loves, for no better reason than that they would come out and see him. The flame becomes a blaze, and years later, he tells us, “the night of August 12, 1967, still divides my life.” Much of the power of Spencer’s story, though, is that even years later David doesn’t seem that far from the seventeen-year-old who acted that night “in full obedience to my heart’s most urgent commands.”

1984 Published: Bright Lights, Big City by Jay McInerney (Vintage Contemporaries, New York)

2006 He wrote the book, David Grossman said later, with the hope it would somehow protect his sons. As Jonathan, the elder son, and then Uri, the younger, enlisted for their military service, Grossman wrote To the End of the Land, the story of an Israeli mother of a soldier, who sets out on a hike through the Galilee with the similar hope that her absence from home will keep away from her door the messengers who deliver the army’s bad news. But the book couldn’t keep them from Grossman’s own door: early on this morning the news arrived that Uri and three soldiers he commanded had been killed by a Hezbollah rocket, just a day before a cease-fire Grossman himself had argued for in a public speech. After sitting shiva, Grossman saw the novel to its finish: “What changed, above all,” he wrote, “was the echo of the reality in which the final draft was written.”

August 13

BORN: 1940 Michael Herr (Dispatches, Walter Winchell), Syracuse, N.Y.

1961 Tom Perrotta (Election, Little Children), Garwood, N.J.

DIED: 2004 Julia Child (Mastering the Art of French Cooking), 91, Montecito, Calif.

2012 Helen Gurley Brown (Sex and the Single Girl), 90, New York City

1841 Skeptical and solitary, Nathaniel Hawthorne was always an unlikely candidate for utopia, and within months of joining the Transcendentalist experiment in communal living at Brook Farm he was lamenting that the work left him even less energy for writing than before. “Even my Custom-House experience was not such a thraldom and weariness,” he wrote his fiancée on this day. “Dost thou think it a praiseworthy matter that I have spent five golden months in providing food for cows and horses? Dearest, it is not so.” Leaving in the fall, he lightly satirized the commune a decade later in The Blithedale Romance, which those who had stayed loyal to the farm resented though it gave their short-lived experiment an immortality.

1912 When he arrived at his friend Max Brod’s house this evening to discuss how to arrange the pieces for his first book to send to the publisher the next day, Franz Kafka was surprised and disconcerted to find a visitor, a cousin of the family, “sitting at the table” though she “looked to me like a maidservant.” Her name was Felice Bauer, and he was, apparently, repelled and attracted at once: coldly assessing her “bony, empty face” and her “blond, somewhat stiff, unattractive hair” in his diary while admitting that “by the time I was seated, I had already formed an immutable opinion.” Saying goodbye at her hotel he stumbled into a revolving door with her and nearly stepped on her foot, and the next day he apologized to Brod for any stupidity with his manuscript that night: “I was completely under the influence of the girl.” A month later he wrote his first of over five hundred letters to her, promising—falsely, as it would turn out—that he was an “erratic letter writer” and “never expect[ed] a letter to be answered by return,” and closing with words that would be innocuous, were he not Franz Kafka: “You might well give me a trial.”

1974 It was the opening day of the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference in Vermont, but one of the star faculty members, John Gardner, scheduled to teach at Bread Loaf for the first time, was nowhere in sight and unreachable until, some days later, he arrived in a new Mercedes he had purchased with the proceeds from one of his recent bestsellers. Shortly after, drunk, he wrecked the Mercedes in a ditch, but despite—or because of—this entrance, he became the dominant presence at Bread Loaf for most of the next decade: combative and charismatic, holding court and hungrily engaging with students’ manuscripts, until, in the fall of 1982, he died when he crashed his Harley-Davidson near Binghamton, New York.

August 14

BORN: 1947 Danielle Steel (The Promise, Fine Things), New York City

1950 Gary Larson (The Far Side), Tacoma, Wash.

DIED: 1951 William Randolph Hearst (publisher, New York Journal), 88, Beverly Hills, Calif.

1963 Clifford Odets (Waiting for Lefty, Awake and Sing!), 57, Los Angeles

1881 According to the memoir of his wife, the naturalist Ernest Thompson Seton hated two men: the late General George Armstrong Custer, for the usual reasons, and his own father, who, following Ernest’s twenty-first birthday, brought out his massive cash book and computed the amount, beginning with the doctor’s fee for his birth, he had spent on his son through his life: $537.50. “Hitherto I have charged no interest,” he continued. “But from now on I must add the reasonable amount of six percent per annum. I shall be glad to have you reduce the amount at the earliest opportunity.” And repay him Seton did, though not before using the next money he earned to leave his Toronto home as quickly as he could, for Manitoba.

1919 Richard Aldington, in the TLS, on Marcel Proust’s À la récherche du temps perdu, vols. 1 and 2: “That which is novel in M. Proust is the deliberate avoidance of the search for novelty. He is the antithesis of a man like Gauguin, always wandering about to find ‘quelques éléments nouveaux.’ ”

1947 “So how did your grandmother die?” “Natural causes.” “What?” “Flood.” In his memoir Running in the Family, Michael Ondaatje recounted his family’s history in Sri Lanka in stories that retain the polished, elliptical style of legend, including the life and death of his grandmother Lalla. An eccentric, alcoholic widow who lived according to means she no longer possessed, Lalla imagined a great death for herself and found it: as storm waters rose around her, she spent this day playing cards and drinking indoors, stayed up through the night—the same night on which, though Ondaatje doesn’t mention it, neighboring India took her independence—and then in the morning walked out her door and was swept away by the floods.

2008 Zadie Smith, in the New York Review of Books, on The BBC Talks of E. M. Forster: “To love Forster is to reconcile oneself to the admixture of banality and brilliance that was his, as he had done himself. In this book that blend is perhaps more perfectly represented than ever before. Whether that’s a good thing or not is difficult to say.”

August 15

BORN: 1771 Walter Scott (Ivanhoe, Rob Roy, Waverley), Edinburgh

1885 Edna Ferber (So Big, Show Boat, Giant), Kalamazoo, Mich.

DIED: 2009 Richard Poirier (A World Elsewhere), 83, New York City

2012 Harry Harrison (Make Room! Make Room!), 87, Brighton, England

1788 In the Almanach des honnêts gens, a radical new calendar in which the French poet and revolutionary Sylvain Maréchal replaced the saints’ names honored in the Christian calendar with the names of philosophers, poets, scientists, and even a courtesan, he left one day blank for future generations to fill: August 15, the date of his own birth.

1947 No literary character is more beholden to the “occult tyrannies” of the calendar than Saleem Sinai, a.k.a. “Snotnose, Stainface, Baldy, Sniffer, Buddha, and even Piece-of-the-Moon,” who was born in the city of Bombay not only on the day of India’s independence from the British Empire (and its partition from Pakistan), but at its very moment, at the midnight hour between August 14 and 15. In Midnight’s Children, his second novel, Salman Rushdie, who himself was born in Bombay two months before Saleem, embraced the narrative possibilities offered by a child born along with his country, going beyond mere symbolism by imagining his hero as one of a handful of children whose midnight births brought them each a superpower, as if they were the X-Men of independent, divided India.

1973 Passing herself off as Zora Neale Hurston’s niece to discourage “foot-dragging” among those who could tell her something about the late writer, who had died in poverty and obscurity thirteen years before, Alice Walker arrived in Eatonville, Florida, the tiny, all-black town Hurston had grown up in. Soon she and a fellow Hurston scholar, Charlotte Hunt, were directed to the graveyard in nearby Fort Pierce where Hurston had been buried without a stone to mark her and, wading into knee-high, snake-friendly weeds, chose a spot for the small monument Walker commissioned reading, “Zora Neale Hurston, ‘A Genius of the South.’ ” Walker’s moving, bittersweet account of their adventure, “In Search of Zora Neale Hurston,” appeared in Ms. in March 1975 and sparked the revival of interest in Hurston that continues to this day.

1982 As someone whose best-known book, and lifelong project, is called Ten Thousand Lives, Ko Un has lived a fair amount of lives himself. A Buddhist monk in his twenties and a poet and teacher (and suicidal alcoholic) in his thirties, he became a leader of the resistance against the South Korean military dictatorship and spent much of his forties in prison, where, in solitary confinement under a life sentence, he began in the darkness of his cell to imagine the faces of all the people he’d known and compose his ongoing poem about their lives as well as those of figures from legend and history. Released from prison under a general amnesty on this day, he has become, in his fifties, sixties, and seventies, the most acclaimed Korean poet.

August 16

BORN: 1902 Georgette Heyer (The Black Moth, The Grand Sophy), London

1902 Wallace Thurman (The Blacker the Berry), Salt Lake City

DIED: 1949 Margaret Mitchell (Gone with the Wind), 48, Atlanta

1998 Dorothy West (The Wedding, The Living Is Easy), 91, Boston

1884 Hugo Gernsback, who was born in Luxembourg on this day, cultivated early interests in electronics, Mars, and the United States, and immigrated to the latter in 1903, where, a fan of Mark Twain, he called himself “Huck” and quickly became a radio entrepreneur. Building a fleet of electronics magazines, he published fiction along with the science, including his own novel Ralph 124C41+, one of the founding books of modern science fiction, though it has been described since as “pitiable,” “simply dreadful,” and “appallingly bad.” In 1926 he launched Amazing Stories, the first magazine devoted to what he called “scientifiction,” starting a ten-year run in which he published many of the early innovators of science fiction while frustrating them with his pathological unwillingness to pay for their work.

1898 When the unnamed narrator of Tayeb Salih’s Season of Migration to the North returns to his village along the Nile after seven years studying in Europe, he wants it to be as it was when he left: the people, his familiar bed, the sound of the wind through the palm trees. But there is a stranger in the village, a man called Mustafa Sa’eed, to whom he’s drawn by an unspoken mutual interest until Mustafa stuns him first by reciting a Ford Madox Ford poem at the end of a drunken evening and then by thrusting a bundle of documents into his hands, including a birth certificate and passport showing years of European travel and a birth date on this day. Mustafa soon disappears from the village, but not before burdening the narrator with the tragic story of his own travels north. For years after, like a figure out of Poe, Mustafa haunts him as a phantom, a double whose legacy he feels doomed to follow.

1922 You’d think Virginia Woolf would have been an ideal reader for Ulysses. Almost exactly Joyce’s age, she was similarly weary of the mechanics of traditional fiction and a fellow experimenter with her characters’ moment-by-moment consciousness. But she could hardly bear to read it. “An illiterate, underbred book it seems to me,” she wrote in her diary on this day after working through the first two hundred pages, “the book of a self-taught working man, & we all know how distressing they are, how egotistic, insistent, raw, striking, & ultimately nauseating. When one can have cooked flesh, why have the raw?” Violently snobbish toward Joyce’s “indecency” and no doubt competitive toward his innovations—“what I’m doing is probably being better done by Mr. Joyce,” she once noted—she finished the book with impatient boredom, eager to get back to reading Proust and to writing Mrs. Dalloway, her own stream-of-consciousness novel set on a single June day.

August 17

BORN: 1932 V. S. Naipaul (A House for Mr. Biswas, A Bend in the River), Chaguanas, Trinidad

1959 Jonathan Franzen (The Corrections, Freedom), Western Spring, Ill.

DIED: 1935 Charlotte Perkins Gilman (The Yellow Wallpaper), 75, Pasadena, Calif.

1973 Conrad Aiken (The Charnel Rose, Ushant), 84, Savannah, Ga.

1854 Bigamy! Insanity! False identities! Arson! The thrillingly convoluted plot of Lady Audley’s Secret, Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s triple-decker novel of Victorian sensation and anxiety, made it one of the most popular novels of the age. Writing soon after the Constance Kent murder case captured English headlines with a similar story of family hatreds and high-profile detective work, Braddon constructed one of the first detective thrillers around the discovery that Lady Audley, the beautiful young wife of wealthy old Sir Michael Audley, wasn’t who she said she was: she had abandoned her old identity (and her previous marriage) and on this day created a new one from scratch, a history, it soon turns out, she is prepared to murder to conceal.

1902 After praising her historical novel, The Valley of Decision, Henry James urged Edith Wharton to write about an American subject, contemporary New York: “the immediate, the real, the ours, the yours, the novelist’s that it waits for . . . Profit, be warned, by my awful example of exile and ignorance.”

1918 Louis Untermeyer, in the New Republic, on Ezra Pound’s Pavannes and Divisions: “It is the record of a creative talent grown sterile, of a disorderly retreat into the mazes of technique and pedantry.”

1924 A sixteenth-century alchemist who declares, “I am wiser by seventy than all such cod-merchants”; a Kansas City lawyer who thinks, “According to the mileage on the speedometer it was time once again to have the Reo lubricated”; his wife, “who was sure that in some way—because she willed it to be so—her wants and her expectations would be the same”; a San Francisco clerk besieged by the ’60s, who fumes, “It could be that Hate is the only reality.” These varied voices, and many others, came from the pen of Evan S. Connell, born on this day, who restlessly transformed himself in book after book, working odd jobs to support his writing for decades until his brilliantly expansive biography of Custer, Son of the Morning Star, became a late-career bestseller.

1936 The Macmillan Company announced that two printing plants were turning out copies of Gone with the Wind for three eight-hour shifts a day, and that if all the copies published so far were stacked, they would reach fifty times the height of the Empire State Building.

1958 Elizabeth Janeway, in the New York Times, on Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita: “The first time I read Lolita I thought it was one of the funniest books I’d ever come on . . . The second time I read it . . . I thought it was one of the saddest.”

August 18

BORN: 1922 Alain Robbe-Grillet (The Voyeur, The Erasers), Brest, France

1974 Nicole Krauss (The History of Love, Great House), New York City

DIED: 1850 Honoré de Balzac (Père Goriot, Eugénie Grandet), 51, Paris

1981 Anita Loos (Gentlemen Prefer Blondes), 92, New York City

1563 Though as a teenager he wrote a political essay against tyranny, “On Voluntary Slavery,” that is still read to this day, Étienne de La Boétie is largely remembered for one reason: as the bosom friend of Michel de Montaigne, who, having spent the previous ten days at La Boétie’s side despite the threat of contagion, recorded his death from plague at 3 a.m. on this day. They had known each other only six years, but it’s often been thought that Montaigne’s retreat to a life of writing, almost a decade after La Boétie’s death, was a way of keeping himself company in the absence of his friend, about whom he wrote, in the essay titled, naturally, “Of Friendship,” “We were halves throughout, to a degree, I think, that by outliving him, I defraud him of his part.”

1912 Among the dozens of poets she wrote to before the launch of her new magazine, Poetry, Harriet Monroe sent a short note to Ezra Pound (via his father, Homer L. Pound, assistant assayer at the U.S. Mint), and on this day Pound replied quickly from London. “I am interested,” he began, sending two poems and offering to keep her “in touch with whatever is most dynamic in artistic thought . . . I do see nearly everyone that matters.” Over the next few years he brought T. S. Eliot, Robert Frost, and H.D., among others, to Poetry before breaking with the magazine in a series of letters whose tone he hinted at in this first note when he added, “However I need not bore you with jeremiads.”

1943 Orville Prescott, in the New York Times, on Betty Smith’s A Tree Grows in Brooklyn: “If you miss ‘A Tree Grows in Brooklyn’ you will deny yourself a rich experience, many hours of delightful entertainment (for it is long), and the pleasant tingle that comes from a sense of discovery.”

1974 It was getting late in the summer, and Rodney Parker, as always, was working the phones: a college basketball coach happy with the two players he sent his way; a fellow fixer who might know a junior college for some of his other kids; a high school coach despondent because Albert King, the impossibly talented 6´5˝ fourteen-year-old, was slipping out of their influence. For a summer, when Brooklyn was a battle zone and the basketball talent pipeline was still a cottage industry, Rick Telander—a white jock nearly as young as the black kids he coached, played against, and wrote about—tried to keep up with Parker’s hustling while gathering the stories for Heaven Is a Playground, a book that over time has gathered for itself some of the aura of the playground legends he chronicled.

August 19

BORN: 1902 Ogden Nash (I’m a Stranger Here Myself), Rye, N.Y.

1903 James Gould Cozzens (Guard of Honor, By Love Possessed), Chicago

DIED: 1662 Blaise Pascal (Pensées, Provincial Letters), 39, Paris

1936 Federico García Lorca (Poet in New York, Blood Wedding), 38, Alfacar, Spain

1890 “I was never fond of towns, houses, society or (it seems) civilization,” Robert Louis Stevenson wrote to Henry James, predicting he’d only return to Britain once, to die (he never made it back at all). “I simply prefer Samoa.”

1903 Did the bloody Battle of Rivington Street between Monk Eastman’s gang and the hooligans loyal to his rival Paul Kelly take place in New York on this day or a month later? The historical evidence points to the latter, but that was of little concern to Jorge Luis Borges when he adjusted and compressed the facts and legends of Eastman’s brutal life into “Monk Eastman, Purveyor of Iniquities,” one of the bloody tales in A Universal History of Infamy, his first collection of fiction. In Borges’s imagination Monk Eastman seems less a real-life Tammany enforcer than a character from Borges’s library; more specifically from Herbert Asbury’s Gangs of New York, from which Borges drew whatever facts about Eastman he didn’t invent out of thin air.

1938 Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s card tricks convinced André Gide he must be clairvoyant.

1946 It tells you a lot about Rosa Burger’s upbringing to know that her parents shoehorned their wedding on this day into the time between their arrest during the black miners’ strike on the Witwatersrand and their court appearance ten days later. Two years afterward, in the same month that the charges were dropped and the Afrikaner nationalist government took office, Rosa, their only daughter, was born, beginning a life in which she has to learn to define for herself an identity as the child of Lionel and Carol Berger, famous enemies of the state, and as a white in the apartheid system, a story that Nadine Gordimer, in Burger’s Daughter, based on the white South African activist families she knew around her.

2009 “Tommy,” the letter Paul Haggis wrote to Scientology spokesman Tommy Davis on this day began. “For ten months now I have been writing to ask you to make a public statement denouncing the actions of the Church of Scientology of San Diego.” And with the same opening began “The Apostate,” Lawrence Wright’s 2011 New Yorker profile of Haggis, the Oscar-winning screenwriter and director of Crash, which ended by quoting Haggis again: “I was in a cult for thirty-four years. Everyone else could see it. I don’t know why I couldn’t.” Two years later, Wright published Going Clear, in which he embedded Haggis’s story in a history of Scientology and its relationship to Hollywood, reported with the same intrepid and patient thoroughness Wright used for his Pulitzer-winning book on al-Qaeda, The Looming Tower.

August 20

BORN: 1890 H. P. Lovecraft (At the Mountains of Madness), Providence, R.I.

1951 Greg Bear (The Forge of God, Darwin’s Radio), San Diego, Calif.

DIED: 1887 Jules Laforgue (The Imitation of Our Lady the Moon), 27, Paris

2001 Fred Hoyle (The Black Cloud), 86, Bournemouth, England

1950 Immanuel Velikovsky asks the reader at the opening of Worlds in Collision “to consider for himself whether he is reading a book of fiction or non-fiction”; the New York Times, at least for the purposes of its bestseller list, where Worlds in Collision spent the last of its eleven weeks at #1 on this day, chose nonfiction. A scientific scandal even before it was published, Velikovsky’s book modestly proposed that as recently as 1500 B.C. Venus spun off as a comet from Jupiter and twice swept past Earth on its way to settling into planetary orbit, thereby explaining a host of ancient mythologies and refuting the theories of both Newton and Darwin. Velikovsky’s conjectures, shaky at the time, have been further undermined by later discoveries, but one element of his thought has gained some acceptance: the importance of catastrophic events in shaping evolutionary and geological history.

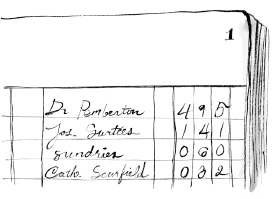

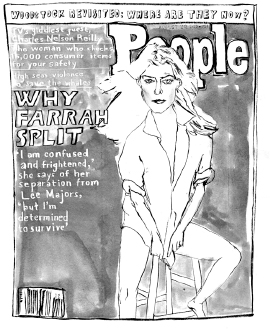

1979 “So Farrah is a story,” explained George W. S. Trow, “and Farrah having a problem is a story, and Farrah talking about her problem is a story.” Many have called TV culture shallow, but none with the chilling insight—and cryptically imperious style—of Trow’s 1980 New Yorker essay “Within the Context of No Context,” which became a little book the following year. Among his evidence that America had given up cultural judgment and authority in favor of popularity: the cover of People on this day. Putting Farrah Fawcett and her problem—that she had split from Lee Majors—on the cover was not a statement of approval or disapproval of Farrah or her talent, as might have once been the case. Instead it was in the spirit of what Trow with grim relish called “the important moment in the history of television,” when Richard Dawson asked Family Feud contestants to guess, not the correct answer to a question, but what a hundred other Americans had already guessed.

2004 Ben Ball, in the TLS, on Elliot Perlman’s Seven Types of Ambiguity: “It paints a convincing portrait of Australia’s cheerfully brazen appeal to greed and comfort; the universities honeycombed with deconstruction; the low hum of racism and sexism; the anxiety that, underneath, there is nothing there.”

August 21

BORN: 1930 Joseph McElroy (Women and Men), New York City

1937 Robert Stone (Dog Soldiers, Children of Light), Brooklyn

DIED: 1940 Leon Trotsky (The History of the Russian Revolution), 60, Mexico City

2007 Siobhan Dowd (Bog Child, The London Eye Mystery), 47, Oxford, England

1888 William Seward Burroughs, founder of what became the Burroughs Corporation and grandfather of William S. Burroughs, received four patents for his adding machines.

1909 “Do you know what a pearl is and what an opal is?” James Joyce wrote to Nora Barnacle. “My soul when you came sauntering to me first through those sweet summer evenings was beautiful but with the pale passionless beauty of a pearl. Your love has passed through me and now I feel my mind something like an opal, that is, full of strange uncertain hues and colours, of warm lights and quick shadows and of broken music.”

1921 On his first birthday, Christopher Milne, known later to everyone but family and friends as Christopher Robin, received a teddy bear that he called “Edward Bear” before settling on “Winnie-the-Pooh.” Four years later, the first Pooh story appeared in print, a Christmastime tale based on the ones Christopher’s father, A. A. Milne, told about him and his stuffed animals Pooh, Eeyore, and Piglet, and in 1926 the book Winnie-the-Pooh was published with illustrations by E. H. Shepard. Shepard based his drawings of Christopher Robin on the real Christopher Milne (who like his father would later weary of the way these stories defined him to the world), but as his model for the immortal Bear of Very Little Brain Shepard used not the real “Pooh” but a teddy bear, known as “Growler,” owned by his own son Graham.

NO YEAR “My mother would not have wanted me to spend my life with this man.” Ellen’s mother, at this point in Amy Bloom’s “Love Is Not a Pie,” is a little box of ashes, but her memory and the presence at her funeral of those who loved her are enough to convince her daughter that “August 21 did not seem like a good date, John Wescott did not seem like a good person to marry, and I couldn’t see myself in the long white silk gown Mrs. Wescott had offered me.” Later that day she’ll hear the words her mother once used to describe the rare and true path her own heart took, “Love is not a pie, dear,” a motto that, like Bloom’s story, happily confounds the limited expectations we—and no doubt John Westcott—often bring to plots involving marriage and adultery.

August 22

BORN: 1920 Ray Bradbury (The Martian Chronicles, Fahrenheit 451), Waukegan, Ill.

1935 Annie Proulx (Brokeback Mountain, The Shipping News), Norwich, Conn.

DIED: 1979 James T. Farrell (Young Lonigan, Judgment Day), 75, New York City

2007 Grace Paley (Enormous Changes at the Last Minute), 84, Thetford, Vt.

1603 “In brief, this is my case: I have completely lost the ability to think or speak coherently about anything at all,” confessed young Philipp, Lord Chandos, in a letter on this day to the writer and philosopher Francis Bacon. Having once written with confidence from within a universe that seemed “one great unity,” he was now overcome by skepticism. The world, especially its humblest elements—a watering can, earthworms under a rotting board, rats suffering death throes from poison—still spoke to him with thrilling intensity, but in a way he could no longer find the words for, so he had to give up writing. It’s a fascinating and challenging declaration—that our words aren’t equal to the world—but one made more ambiguous by the sheer eloquence with which its author proclaims the insufficiency of language. That its author was not the fictitious Lord Chandos, writing in 1603, but Hugo von Hofmannsthal, writing in 1902—and that Hofmannsthal did not give up writing after publishing it—only adds to the letter’s ambiguity, and its fascination.

1762 Edward Gibbon dined with a Captain Perkins, who afterward led him “into an intemperance we have not known for some time past.”

1903 One reason William James has remained an interesting thinker is that he paired a desire to establish a Big Idea with a skepticism that such a thing was possible or even worthwhile. “I am convinced that the desire to formulate truths is a virulent disease,” he wrote a friend on this day while struggling to compose a major work of philosophy. “I actually dread to die until I have settled the Universe’s hash in one more book . . . Childish idiot—as if formulas about the Universe could ruffle its majesty, and as if the common-sense world and its duties were not eternally the really real!” And so it’s appropriate that the next book he published, Pragmatism, has ever since been taken by some as a slight work of little philosophical importance, and by others as every bit the “epochmaking” work James had childishly hoped for.

1930 After his horse bolted in Wyoming, Ernest Hemingway required stitches on his chin.

1934 Malcolm Cowley, in the New Republic, on the stories of Somerset Maugham: “Reading these thirty stories one after another is like sitting for a long time in a room where people are playing bridge and gossiping in even voices. The room may be east or west, in London or Singapore, but the people in it are always the same: they are the Britons of good family who administer the Empire under the direction of its actual rulers. They know what is done and what is not done.”

August 23

BORN: 1926 Clifford Geertz (The Interpretation of Cultures), San Francisco

1975 Curtis Sittenfeld (Prep, American Wife), Cincinnati

DIED: 1723 Increase Mather (A Further Account of the Tryals of the New-England Witches), 84, Boston

2012 James Fogle (Drugstore Cowboy), 75, Monroe, Wash.

1872 The Pickwick Portfolio, the household newspaper written by the March girls in Little Women, is, Louisa May Alcott assures her readers, “a bona fide copy of one written by bona fide girls once upon a time”—one in fact, that Alcott and her sisters produced during her own childhood. Her story later came full circle when five sisters in Pennsylvania, the Lukens, were inspired by the March girls to start their own homemade journal, Little Things. Handwritten at first but typeset by its third issue, in two years the Lukens’ journal had a thousand subscribers, including Miss Alcott herself, who wrote them on this day, “I admire your pluck and perseverance and heartily believe in women’s right to any branch of labor for which they prove their fitness.”

1948 Before he ever set out with Neal Cassady, Jack Kerouac jotted down in his journal an idea for a future book, “about two guys hitch-hiking to California in search of something they don’t really find, and losing themselves on the road, and coming all the way back hopeful of something else.”

1956 Attacked by the Nazis in Germany and hounded out of Norway in the ’30s, Wilhelm Reich, the radical psychoanalyst who claimed to have discovered a life force known as “orgone energy,” had a quieter time of it during his first eight years in the United States, where his work attracted the attention of, among others, Norman Mailer and William Steig. But after a series of articles in the New Republic in 1947 warned of a “growing Reich cult,” the Federal Drug Administration challenged the medical claims for the therapeutic boxes he called “orgone accumulators,” and in 1956 began the destruction of his work, arresting Reich, chopping up the orgone boxes at his headquarters in Orgonon, Maine, and, on this day, forcing his associates to feed six tons of his journals and books into the New York City Sanitation Department’s Gansevoort Street incinerator in the West Village.

NO YEAR It was two years after Christopher’s mother went to the hospital and died—or so he’d been told—that he found, in a box in his father’s closet, a stack of letters he’d never been shown, all addressed to him and dated—May 3, September 18, August 23—after she died. Telling of her new life in London and explaining why she had to leave their family, the letters add another mystery to the ones Christopher, the autistic narrator of Mark Haddon’s The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time, is already investigating: the death of the dog next door and the constant riddle of the human emotions he finds so incomprehensible.

August 24

BORN: 1899 Jorge Luis Borges (A Universal History of Infamy), Buenos Aires

1977 John Green (Paper Towns, The Fault in Our Stars), Indianapolis

DIED: 1943 Simone Weil (Waiting for God, The Need for Roots), 34, Ashford, England

2004 Elisabeth Kübler-Ross (On Death and Dying), 78, Scottsdale, Ariz.

1770 Thomas Chatterton gained little of the fame he desired during his life, but his apparent suicide by arsenic on this day at the age of seventeen has reverberated through the following centuries. The Romantics took up his memory—Keats wrote him a sonnet, and Wordsworth called him the “marvellous boy”—and in 1856 the painter Henry Wallis posed the poet George Meredith, sprawled red-haired in a garret, for his popular portrait Death of Chatterton. And in the following century Peter Ackroyd put the poet’s death at the heart of Chatterton, a multilayered novel that takes advantage of the irresistible biographical detail that less than a year after Wallis painted Meredith, Meredith’s wife, Mary, left her husband for the man who had posed him as the doomed poet.

1814 At the ugly house they had just been forced by poverty to rent in Switzerland, Mary and Percy Bysshe Shelley walked to the nearby lakeshore and read Tacitus’s description of the Siege of Jerusalem. Then “we come home, look out the window, and go to bed.”

1935 “The thing I think about most,” Evelyn Waugh wrote to Laura Herbert from Ethiopia, “is your eyelashes making a noise like a bat on the pillow.”

1962 Having traveled by bus up to northern California’s Portola Valley from Mexico City, where he had secluded himself from the buzz created when his first novel, V., was published that spring, Thomas Pynchon stood as best man in the wedding of his close college friend—and soon-to-be fellow novelist—Richard Fariña to Mimi Baez, the eighteen-year-old sister of Joan Baez (whose boyfriend Bob Dylan did not attend). In photographs taken by the mother of the groom but never publicly released, the reclusive best man, dressed in a dark suit, is said to sport a giant mustache that may or may not have been fake.

1975 “To learn to write at all,” Joanna Russ wrote James Tiptree Jr. (who later revealed herself to be a woman named Alice Sheldon), “I had to begin by thinking of myself as a sort of fake man, something that ended only with feminism.”

August 25

BORN: 1921 Brian Moore (Black Robe, Lies of Silence), Belfast, Northern Ireland

1949 Martin Amis (Money, Time’s Arrow), Swansea, Wales

DIED: 1900 Friedrich Nietzsche (Beyond Good and Evil), 55, Weimar, Germany

1984 Truman Capote (Breakfast at Tiffany’s, In Cold Blood), 59, Los Angeles

1793 When contemporary readers of Charles Brockden Brown’s novel Arthur Mervyn saw its opening line, “I was resident in this city during the year 1793,” they knew exactly what his narrator was speaking of. The city was Brown’s own, Philadelphia, the largest in the new country. And the year 1793 meant fever: the yellow fever epidemic that killed over 4,000 of the city’s 50,000 residents. Nearly half of those residents fled the city, especially after the local doctors on this day published a list of measures to corral the spread of the disease. Brockden Brown—not the first American novelist but the first good one—vividly describes that flight in Arthur Mervyn, a wonderfully intense Gothic drama in which urban disease and commerce are equal causes of anxiety and intrigue.

1900 In the last of a three-day match between Marylebone Cricket Club and London County, Arthur Conan Doyle, taking a turn at bowling, dismissed the batter considered the greatest cricketer of all time, W. G. Grace, for his only first-class wicket.

1909 Fat and thin, Catholic and skeptic, individualist and socialist, carnivore and vegetarian, tippler and teetotaler, mustachioed and bearded: G. K. Chesterton and G. B. Shaw were seen as almost comical opposites when they regularly and affectionately locked antlers at the turn of the twentieth century, a combat that culminated in Chesterton’s biography of Shaw in 1909, which Shaw himself reviewed in the Nation on this day. Shaw called its “account of my doctrine” “either frankly deficient and uproariously careless or else recalcitrantly and . . . madly wrong,” but nevertheless called himself “proud to have been the painter’s model.” Another reviewer, meanwhile, suggested that Shaw had wearied of his beliefs but couldn’t give up the fame they had brought him, and so invented his amicable opponent, “Chesterton.”

1938 Running as a Democrat for California assemblyman in the 59th District, Robert A. Heinlein lost to the incumbent by 450 votes.

1950 With an operating budget of $1,434,789 and the ambivalent support of its studio, MGM, John Huston’s prestige production of The Red Badge of Courage began shooting its first battle scenes on a day in Chico, California, that reached 108 degrees. On the set was Lillian Ross, the New Yorker reporter whose genial unobtrusiveness and flawless recall of dialogue captured, among other details, the comments a few weeks later of an MGM publicity man: “Two things sell tickets. One, stars. Two, stories. No stars, no stories here.” When preview audiences for the movie agreed and tore the picture to shreds, Ross had a story of her own to tell, and Picture, her groundbreaking inside account of the shooting of the movie (and its panicked re-editing), found a success its subject didn’t.

August 26

BORN: 1880 Guillaume Apollinaire (Calligrammes, Alcools), Rome

1941 Barbara Ehrenreich (Nickel and Dimed, Fear of Falling), Butte, Mont.

DIED: 1945 Franz Werfel (The Forty Days of Musa Degh), 54, Los Angeles

1989 Irving Stone (Lust for Life, The Agony and the Ecstasy), 86, Los Angeles

1881 “I wonder again,” Henry Holmes Goodpasture writes in his journal at the opening of Oakley Hall’s Warlock, “how we manage to obtain deputies at all.” Yet another has just been run off from the town of Warlock, a good one at that, but too prudent not to leave when Abe McQuown started firing into the air in the middle of town. Nevertheless, on this day the good Mr. Goodpasture can report that the ad hoc Citizens’ Committee has brought in a man of significant reputation as marshal, one Clay Blaisedell, who carries a renown embodied in the gold-handled Colts he is known to brandish. A free-handed rewrite of the already-familiar events of the Gunfight at the OK Corral, Warlock is a refreshingly impure, almost effortlessly hilarious, and claustrophobically bleak epic of the West.