October If you like fall, you like October. It’s the height of the season, the fieriest in its orange, the briskest in its breezes. “I’m so glad I live in a world where there are Octobers,” exclaims the irrepressible Anne Shirley in Anne of Green Gables. “It would be terrible if we just skipped from September to November, wouldn’t it?” October at Green Gables is “when the birches in the hollow turned as golden as sunshine and the maples behind the orchard were royal crimson” and “the fields sunned themselves in aftermaths”: it’s a “beautiful month.”

Katherine Mansfield would have disagreed. October, she wrote in her journal, “is my unfortunate month. I dislike exceedingly to have to pass through it—each day fills me with terror.” (It was the month of her birthday.) And Gabriel García Márquez’s biographer notes that October, the month of the greatest disaster in his family history, when his grandfather killed a man in 1908, “would always be the gloomiest month, the time of evil augury” in his novels.

Some people, of course, seek out evil augury in October. It’s the month in which we domesticate horror, as best we can, into costumes, candy, and slasher films. Frankenstein’s monster may not have been animated until the full gloom of November, but it’s in early October that Count Dracula visits Mina Harker in the night and forces her to drink his blood, making her flesh of his flesh. And it’s in October that the Overlook Hotel shuts down for the season, leaving Jack Torrance alone for the winter with his family and his typewriter in The Shining, and it’s in October that his son, Danny, starts saying “Redrum.”

Can you domesticate horror by telling scary tales? Just as the camp counselor frightening the campers around the fire is likely the first one to get picked off when the murders begin, the four elderly members (who used to be five) of the Chowder Society in Peter Straub’s Ghost Story, who have dealt with the disturbing death of one of their own the previous October by telling each other ghost stories, prove anything but immune to sudden terror themselves until they can trace their curse to a horrible secret they shared during an October fifty years before—just after, as it happens, another kind of modern horror, the stock market crash of 1929. In the odd patterns that human irrationality often follows, those financial terrors, the Black Thursdays and Black Mondays, tend to arrive in October too.

RECOMMENDED READING FOR OCTOBER

The Gambler by Fyodor Dostoyevsky (1867)  Those planning to celebrate National Novel Writing Month in November can take heart—or heed—from Dostoyevsky’s bold wager in October 1866, made to pay off his gambling debts, that if he couldn’t write a novel in a month he would lose the rights to his next nine years of work. The subject he chose won’t surprise you.

Those planning to celebrate National Novel Writing Month in November can take heart—or heed—from Dostoyevsky’s bold wager in October 1866, made to pay off his gambling debts, that if he couldn’t write a novel in a month he would lose the rights to his next nine years of work. The subject he chose won’t surprise you.

Ghost Stories of an Antiquary by M. R. James (1904)  James had modest aims for the wittily unsettling tales, often set among the libraries and ancient archives that were his professional haunts, that he wrote to entertain his students at Eton and Cambridge. But their skillful manipulation of disgust has made them perennial favorites for connoisseurs of the macabre.

James had modest aims for the wittily unsettling tales, often set among the libraries and ancient archives that were his professional haunts, that he wrote to entertain his students at Eton and Cambridge. But their skillful manipulation of disgust has made them perennial favorites for connoisseurs of the macabre.

Ten Days That Shook the World by John Reed (1919)  Oddly, one effect of the Russian Revolution was to modernize the calendar so the October Revolution, in retrospect, took place in November. But wherever you place those ten days, Reed, the partisan young American reporter, was there, moving through Petrograd—soon to be Leningrad—as the very ground shifted underneath him.

Oddly, one effect of the Russian Revolution was to modernize the calendar so the October Revolution, in retrospect, took place in November. But wherever you place those ten days, Reed, the partisan young American reporter, was there, moving through Petrograd—soon to be Leningrad—as the very ground shifted underneath him.

Peyton Place by Grace Metalious (1956)  The leaves are turning red, brown, and yellow in the small New England town, while the sky is blue and the days are unseasonably warm: it must be Indian summer. But let’s hear Grace Metalious tell it: “Indian summer is like a woman. Ripe, hotly passionate, but fickle.”

The leaves are turning red, brown, and yellow in the small New England town, while the sky is blue and the days are unseasonably warm: it must be Indian summer. But let’s hear Grace Metalious tell it: “Indian summer is like a woman. Ripe, hotly passionate, but fickle.”

A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle (1962)  It’s a dark and stormy October night when Meg comes downstairs to find Charles Wallace waiting precociously for her with milk warming on the stove. Soon after, blown in by the storm, arrives their strange new neighbor Mrs. Whatsit, “her mouth puckered like an autumn apple.”

It’s a dark and stormy October night when Meg comes downstairs to find Charles Wallace waiting precociously for her with milk warming on the stove. Soon after, blown in by the storm, arrives their strange new neighbor Mrs. Whatsit, “her mouth puckered like an autumn apple.”

The Dog of the South by Charles Portis (1979)  There’s no particular reason to read The Dog of the South in October except that it begins in that month, when the leaves in Texas have gone straight from green to dead, and Ray Midge’s wife, Norma, has run off with his credit cards, his Ford Torino, and his ex-friend Guy Dupree. Any month is a good month to read Charles Portis.

There’s no particular reason to read The Dog of the South in October except that it begins in that month, when the leaves in Texas have gone straight from green to dead, and Ray Midge’s wife, Norma, has run off with his credit cards, his Ford Torino, and his ex-friend Guy Dupree. Any month is a good month to read Charles Portis.

Black Robe by Brian Moore (1985)  It’s Indian summer in Black Robe too, but the warm days are ending and winter’s coming on when Father Laforgue begins his journey to a remote Huron settlement. Based on the letters sent by seventeenth-century Jesuit missionaries in North America, Black Robe dramatizes the familiar clash of cultures in deeply unfamiliar but sympathetic ways.

It’s Indian summer in Black Robe too, but the warm days are ending and winter’s coming on when Father Laforgue begins his journey to a remote Huron settlement. Based on the letters sent by seventeenth-century Jesuit missionaries in North America, Black Robe dramatizes the familiar clash of cultures in deeply unfamiliar but sympathetic ways.

The Road by Cormac McCarthy (2006)  The landscape McCarthy’s father and son travel has been razed of all civilization, and calendars have gone with it, but as their story begins the man thinks it might be October. All he knows is that they won’t last another winter without finding their way south.

The landscape McCarthy’s father and son travel has been razed of all civilization, and calendars have gone with it, but as their story begins the man thinks it might be October. All he knows is that they won’t last another winter without finding their way south.

October 1

BORN: 1914 Daniel J. Boorstin (The Image, The Discoverers), Atlanta

1946 Tim O’Brien (The Things They Carried), Austin, Minn.

DIED: 2004 Richard Avedon (Portraits), 81, San Antonio

2012 Eric Hobsbawm (The Age of Revolution), 95, London

1835 “Doves & Finches swarmed round its margin,” Charles Darwin wrote on this day about a tiny pool of water on Albemarle Island in the Galápagos, the only mention he made in the diaries of his five-year journey on the HMS Beagle of the birds that would play a central role in his theory of natural selection and that would later bear his name. Nevertheless, he brought samples of them home, as he did of countless of the islands’ species, and by the time he published his account of the trip in The Voyage of the Beagle in 1839, he was able to theorize that the remarkable variation in the small group of bird species later known as “Darwin’s finches” was due to their isolation from each other on the various islands of the archipelago.

1888 L. Frank Baum opened Baum’s Bazaar on Main Street in Aberdeen, South Dakota, offering housewares, toys, and the “latest novelties in Japanese Goods, Plush, Oxidized Brass and Leather Novelties.” It failed a year later.

NO YEAR Danny the Champion of the World, set in a countryside much like that in which Roald Dahl’s tiny writing shed stood, was one of Dahl’s own favorites. It’s the least fantastic of his tales for children, except that few things are more fantastic for a boy than to have “the most marvelous and exciting father any boy ever had,” especially one who conspires with his son to capture over a hundred tranquilized pheasants and construct a Special Extra-large Poacher’s Model baby carriage to transport them, thereby ruining the grand shooting party hosted every year on the opening day of pheasant season by Mr. Victor Hazell, the piggy-eyed snob with the “glistening, gleaming Rolls-Royce” that won’t be so glistening or gleaming once the pheasants have done with it.

2008 Having been named the “chief artist” of the newspaper Izvestia a year before on his 108th birthday, political cartoonist Boris Yefimov died on this day in Moscow at the age of 109. Born in Kiev at the end of the nineteenth century, he lived his childhood under the tsar and then for ninety years chronicled the tumultuous history of the Soviet Union and its dissolution, caricaturing its enemies as they changed and always keeping close enough to the party line to survive its many purges (his first book had a foreword by his friend Trotsky, whom he soon had to draw as an enemy of the state). After Stalin executed his brother, a famous journalist who was the model for Karkov in Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls, Yefimov thought he’d be next, but he even survived the experience of having Stalin personally suggest and edit his cartoons.

October 2

BORN: 1879 Wallace Stevens (Harmonium, Ideas of Order), Reading, Pa.

1904 Graham Greene (The Heart of the Matter), Berkhamsted, England

DIED: 2002 Norman O. Brown (Life Against Death), 89, Santa Cruz, Calif.

2005 August Wilson (The Piano Lesson, Fences), 60, Seattle

1822 Mary Shelley began her journal again for the first time since Percy Bysshe Shelley drowned in July: “Now I am alone—oh, how alone! The stars may behold my tears, and the winds drink my sighs; but my thoughts are a sealed treasure, which I can confide to none.”

1830 In the two days since she met the Reverend Edward Casaubon, who seemed at once the “most interesting man she had ever seen” and the “most distinguished-looking,” young Dorothea Brooke’s affection for this sallow, middle-aged bookworm has blossomed. After all, she notes decisively to her flightier sister, “Everything I see in him corresponds to his pamphlet on Biblical Cosmology.” And when Mr. Casaubon, on making his goodbyes on this brisk day, alludes drily to his need for young companionship, Dorothea, glowing with the prospect of matrimony, prepares for an ill-fated decision that George Eliot is too good a novelist, and Middlemarch too great a novel, to make the end of her story.

1950 “Well! Here comes ol’ Charlie Brown!” says Shermy to Patty in the first line in Charles M. Schulz’s new comic strip. “How I hate him!”

1957 Julia Child wrote to Avis DeVoto that she had caught up with the bestselling Peyton Place: “Those women, stroked in the right places until they quiver like old Stradivarii! Quite enjoyed it, though feeling an underlying abyss of trash.”

1968 Djuna Barnes remarked to a friend on Anaïs Nin: “Something of a pathological ‘little girl’ lost—sometimes a bit ‘sticky,’ she sees too much, she knows too much, it is intolerable.”

1975 Ann Rule’s career as the “Queen of True Crime” began with a haunting coincidence. A mother of four, she was writing for True Detective magazine under the pen name Andy Stark and taking forensic science classes when an old friend she had worked nights with on a crisis hotline called to ask if she knew why police were looking into his records. A few days later, on this day, that friend, Ted Bundy, was arrested in Utah for kidnapping, and the next morning wired a message to Rule in Seattle: “Ted Bundy wants you to know that he is all right, that things will work out.” Rule’s first book, The Stranger Beside Me, describes how things did work out, and how Rule came to learn the true story of the serial killer she had once thought of as “almost the perfect man.”

October 3

BORN: 1924 Harvey Kurtzman (editor of Mad and Help!, Little Annie Fanny), Brooklyn

1925 Gore Vidal (Burr, Julian, Myra Breckinridge), West Point, N.Y.

DIED: 1896 William Morris (News from Nowhere, Kelmscott Press), 62, London

1967 Woody Guthrie (Bound for Glory), 55, New York City

1802 On the night before her brother, William, married her friend Mary Hutchinson, Dorothy Wordsworth wore Mary’s wedding ring on her own finger while she slept.

1860 Sailing north from the equator toward San Francisco, his last novel published three years before, Herman Melville marked this passage in his copy of Chapman’s Homer with an underline and an exclamation: “The work that I was born to do is done!”

1918 It wasn’t until he was thirty-seven, with four novels published and one, Maurice, written but kept secret because of the gay relationship at its heart, that E. M. Forster first had sex. Stationed in Egypt with the Red Cross during the war, he confessed in coded language to a friend, “Yesterday, for the first time in my life I parted with respectability. I have felt the step would be taken for many months. I have tried to take it before. It has left me curiously sad.” But he wasn’t sad at all when, a few years later, he fell in love with an Egyptian man. “I am so happy,” he wrote on this day. “I wish I was writing the latter half of Maurice now. I know so much more. It is awful to think of the thousands who go through youth without ever knowing.”

1933 Lacking the $1.83 in postage to submit the manuscript of her first book, Jonah’s Gourd Vine, to a publisher, Zora Neale Hurston prevailed upon the local chapter of the Daughter Elks to borrow the funds from their treasury.

1951 It’s the set piece to end all set pieces: Sinatra, Gleason, and Hoover in the stands, Durocher, Maglie, Robinson, and Mays on the field, Ross Hodges on the mic, and the Giants and the Dodgers playing for the pennant. Branca throws to Thomson, Gleason throws up on Sinatra’s shoes, Pafko goes back to the wall, the Giants win the pennant, and a kid named Cotter Martin runs off with the ball. Published as a special insert in Harper’s in 1992 and as a book of its own in 2001, “Pafko at the Wall” also stands as the masterful prologue to Don DeLillo’s 1997 epic, Underworld.

1999 Verlyn Klinkenborg, in the New York Times, on Kent Haruf’s Plainsong: “Haruf has made a novel so foursquare, so delicate and lovely, that it has the power to exalt the reader.”

2008 Will Heinrich, in the New York Observer, on Stieg Larsson’s The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo: “To call the dialogue wooden would be an insult to longbows and violins. And yet, I had no trouble finishing the book—on the contrary, I raced through it, even while I disliked it, and myself for reading it.”

October 4

BORN: 1937 Jackie Collins (Hollywood Wives, The Stud), London

1941 Anne Rice (Interview with the Vampire), New Orleans

DIED: 1974 Anne Sexton (The Awful Rowing Toward God), 45, Weston, Mass.

1988 Geoffrey Household (Rogue Male), 87, Banbury, England

1866 Made desperate by his debts, Fyodor Dostoyevsky reluctantly signed in July 1865 an agreement whose predatory conditions might well have come from a fairy tale: if he failed to complete a 160-page novel by November 1, 1866, his publisher would have the right to all his works for the next nine years without compensation. He paid off some creditors with the rubles and gambled away the rest, but, busy with another book, Crime and Punishment, he put off the contracted novel until this day, less than a month before his deadline, when he finally engaged a young stenographer, Anna Grigorievna, to help him. He dictated the story of The Gambler to her every afternoon, turned in the manuscript two hours before the deadline, and then, when they met a week later to resume his work on Crime and Punishment, asked for Anna’s hand in marriage, which she granted.

1981 Bernd Heinrich was a quickly rising star professor in the field of entomology (he had published extensively on bumblebees), and was beginning a career in nature writing that would later include The Mind of the Raven and Winter World, but to the other runners at the start of the North American 100 km ultramarathon championship he was an unknown (though he had won the Masters Division of the Boston Marathon the year before). He’d never competed at any length beyond the marathon before, but, using his expertise in animal physiology, he’d trained all summer in the Maine woods while doing his biological fieldwork and by the end of the race he had set, at age forty-one, a new American 100 km record of 6:38:20 (that’s sixty-two 6:40 miles), a mark that stood for over a decade and an experience that’s the climax of his book on the human and animal capacities for endurance, Why We Run.

1986 The New York District Attorney’s office may have eventually been satisfied that the wondrously bizarre attack on Dan Rather this evening—in which the CBS newsman was beaten by two well-dressed men shouting, “Kenneth, what is the frequency?”—was perpetrated by a paranoid delusional named William Tager, but Paul Limbert Allman has suggested another suspect: the late, bearded fabulist Donald Barthelme. Writing in Harper’s in 2001 (and later adapting his article for the stage), Allman assembled his clues—the striking appearance of the phrase “What is the frequency?” and a character named Kenneth in Barthelme’s Sixty Stories, along with the fact that Rather and Barthelme, Texans born just six months apart, likely knew each other as reporters in Houston in the 1960s—into a deadpan tale that, if it never quite reaches plausibility, at least has the makings of a good Barthelme story.

October 5

BORN: 1949 Bill James (Bill James Baseball Abstract), Holton, Kans.

1952 Clive Barker (Books of Blood, Weaveworld, Abarat), Liverpool

DIED: 1962 Sylvia Beach (Shakespeare & Company), 75, Paris

2003 Neil Postman (Amusing Ourselves to Death), 72, New York City

1814 Percy Bysshe Shelley read Coleridge’s “Rime of the Ancient Mariner” aloud to Mary Godwin.

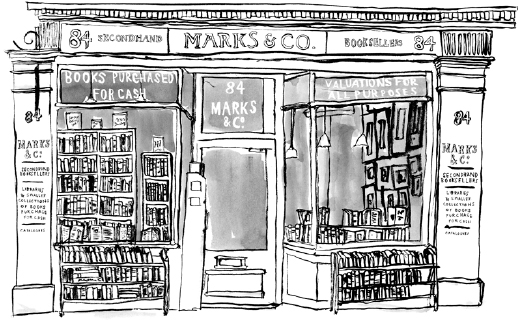

1927 She had been mulling the idea for months—a fictional biography of her friend Vita Sackville-West, with whom she’d had a short affair and a long fascination—and on this day, her other work done, Virginia Woolf allowed herself to begin it: “a biography beginning in the year 1500 & continuing to the present day, called Orlando: Vita; only with a change about from one sex to another.” She quickly gave herself up “to the pure delight of this farce,” and then asked her subject’s permission to write about “the lusts of your flesh and the lure of your mind.” Vita was equally delighted: “What fun for you; what fun for me,” she replied. “Yes, go ahead, toss up your pancake, brown it nicely on both sides, pour brandy over it, and serve hot.”

1937 Richard Wright, in the New Masses, on Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God: “Her novel is not addressed to the Negro, but to a white audience whose chauvinistic tastes she knows how to satisfy.”

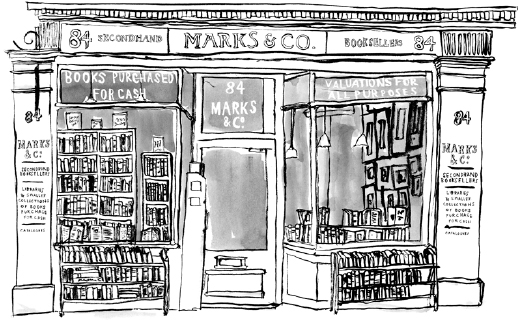

1949 “Gentlemen: Your ad in the Saturday Review of Literature says that you specialize in out-of-print books.” So began, with uncharacteristic formality, the first letter Helene Hanff, a television scriptwriter and book-loving Anglophile in New York, sent to Marks & Co., a London bookshop located at 84, Charing Cross Road, in search of essays by Hazlitt, Stevenson, and Hunt. She soon sloughed off her initial propriety (“I hope ‘madam’ doesn’t mean over there what it does over here,” she remarked in her second letter), but it took over two years for her London bookselling correspondent, Frank Doel, to drop the “Miss Hanff” for “Helene” and more than two decades for Hanff to cross the Atlantic for her long-promised visit to the shop. By that time Doel had died, but their letters had already been immortalized in the collection 84, Charing Cross Road.

October 6

BORN: 1895 Caroline Gordon (None Shall Look Back), Todd County, Ky.

1914 Thor Heyerdahl (Kon-Tiki, Aku-Aku), Larvik, Norway

DIED: 1892 Alfred Tennyson (In Memoriam A.H.H., Idylls of the King), 83, Lurgashall, England

1979 Elizabeth Bishop (North & South, A Cold Spring), 68, Boston

1536 The unapproved possession of a Bible translated into English was a crime in England punishable by excommunication or death when William Tyndale, a graduate of Oxford with half a dozen languages at his command, moved to Germany in 1524 and began his own translation of the New Testament. By 1526 copies of his translation were being smuggled back into England, and a decade later, while living in Antwerp, Tyndale was arrested and convicted of heresy by the Holy Roman Emperor. Tradition has it that this is the day he was strangled and burned to death, with the final words “Lord, open the King of England’s eyes.” Not long after, Henry VIII did indeed approve an English translation of the Bible, and when King James commissioned his own version in the next century, a majority of its words were taken from Tyndale’s once-heretical translation.

1834 From 1832, when a woman in Odessa sent him an anonymous fan letter signed “The Stranger,” to 1850, just months before his death, when he married his admirer, who turned out to be a Polish noblewoman named Eveline Hańska, Honoré de Balzac carried on the most passionate correspondence of his life. He had to wait for her hand until the death of her husband and then had to compete with, among others, Franz Liszt for her affections. In return, he always declared she only had one competitor for his heart: his work on the vast series of novels called the Comédie humaine he outlined to her on this day. “I have now shown you my real mistress,” he confessed. “I have removed her veils . . . [T]here is she who takes my nights, my days, who puts a price on this very letter, taken from hours of study—but with delight.”

1919 When she moved into shared lodgings with Ivy Compton-Burnett on this day, Margaret Jourdain was already a grand figure: a poet, an admired authority on English furniture and interior design, and the sharp-tongued center of an active social circle. Ivy was the opposite: withdrawn and drab, fading into the wallpaper (the provenance of which Margaret was no doubt an expert). So when Ivy began in the next decade to gain a small but shocking celebrity from her novels, their circle was horrified, not only at the vaguely disreputable activity of novel-writing, but that it was Ivy, the nonentity, who was becoming known by scribbling away behind her silent facade. Even Margaret claimed she had been unaware that her companion had published a novel at all until she produced Pastors and Masters “from under the bedclothes.”

October 7

BORN: 1964 Dan Savage (Savage Love, The Kid), Chicago

1966 Sherman Alexie (The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian), Wellpinit, Wash.

DIED: 1849 Edgar Allan Poe (“The Tell-Tale Heart,” “The Purloined Letter”), 40, Baltimore

1943 Radclyffe Hall (The Well of Loneliness, Adam’s Breed), 63, London

1804 It’s not until halfway through his Confessions of an English Opium-Eater that Thomas de Quincey eats his first opium. After twenty days of unbearable pain from toothache and rheumatism he went out on a “wet and cheerless” London Sunday that one biographer places in early October, met a college friend who suggested opium, and obtained a tincture at a druggist. It did not merely ease his pain. “Here was a panacea,” he remembered almost twenty years later when he was in the depths of addiction, “for all human woes . . . Happiness might now be bought for a penny, and carried in the waistcoat-pocket.” His daily doses didn’t begin for another decade, but the forty years after that were consumed in desperate cycles of consumption and withdrawal.

1924 Having finally read the manuscript of T. E. Lawrence’s Seven Pillars of Wisdom after spending two years attempting to arrange its publication, George Bernard Shaw reprimanded the young soldier about his punctuation: “You practically do not use semicolons at all. This is a symptom of mental defectiveness, probably induced by camp life.”

1955 Jack Kerouac, passing jugs of red wine around the audience, couldn’t be convinced to come up and read his work, but the crowd of a hundred or so at a San Francisco auto-repair-shop-turned-performance-space called Six Gallery recognized that the five poets who did read—Philip Lamantia, Michael McClure, Philip Whalen, Allen Ginsberg, and Gary Snyder—had done something rare: they had changed poetry. Or rather Ginsberg had, in just his second public performance and his first reading of Howl, the first part of which he had composed a month and a half before in one blow, “sounding like you,” he wrote Kerouac, “an imitation practically.” At the reading, as Ginsberg built to his anguished and ecstatic climax, Kerouac drummed on a wine jug and yelled “Go!” from the audience for rhythm.

1971 Michael Ratcliffe, in the Times, on E. M. Forster’s posthumous Maurice: “It doesn’t work . . . Two of Forster’s strongest cards—the spirit of place and the fringe of emasculating women—are scarcely played at all, though he holds them in his hand and needs them to win this particular game like no other.”

October 8

BORN: 1917 Walter Lord (A Night to Remember, Day of Infamy), Baltimore

1920 Frank Herbert (Dune, God Emperor of Dune), Tacoma, Wash.

DIED: 1754 Henry Fielding (Tom Jones, Joseph Andrews), 47, Lisbon

1945 Felix Salten (Bambi, Josephine Mutzenbacher), 76, Zurich

1762 After receiving a turtle on his nomination to local office, Edward Gibbon hosted a dinner for forty-eight supporters consisting of “six dishes of turtle, eight of Game with jellies, Syllabubs, tarts, puddings, pine apples, in all three and twenty things besides a large piece of roast beef on the side.”

1818 The vicious, class-baiting contempt with which John Keats’s Endymion was greeted is well known: “Back to the shop Mr John, back to plasters, pills, and ointment boxes,” scoffed Blackwood’s about his “imperturbable drivelling idiocy.” Some, including Lord Byron, have claimed the bad reviews drove the young poet to his death, but Keats himself, though wounded, showed a resilient indifference in a letter to his publisher on this day. He was his own fiercest critic, after all: “My own domestic criticism has given me pain without comparison beyond what Blackwood or the Quarterly could possibly inflict.” With his “slipshod Endymion,” he added, he had “leaped headlong into the Sea, and thereby have become better acquainted with the Soundings, the quicksands, and the rocks, than if I had stayed upon the green shore, and piped a silly pipe, and took tea and comfortable advice. I was never afraid of failure; for I would sooner fail than not be among the greatest.”

1846 To Louise Colet, jealous of a letter he had written an old flame, Gustave Flaubert protested that he didn’t seriously love the other woman, or rather, that he did, “but only when I was writing.”

1945 One story begins, “He came into the world in the middle of a thicket, in one of those little, hidden forest glades.” The other opens, “The saying is that young whores eventually become old religious crones, but that was not my case.” During his prolific Viennese career, Felix Salten, who died on this day, was best known as the author of the first novel, Bambi, which became an American bestseller (translated by Alger Hiss’s future antagonist, Whittaker Chambers) well before it found its way to Walt Disney. Disney adapted two more of Salten’s stories, but he never would have touched the second book above: Josephine Mutzenbacher, a legendary, often banned, and anonymously published pornographic novel that has sold millions. Salten never acknowledged he wrote it, but scholars have come to believe the speculation that he did, and after his death his family even sued (unsuccessfully) to claim its significant royalties.

1964 His Canadian publisher, Jack McClelland, informed Mordecai Richler that “you are absolutely out of your mind. Why in hell anybody would turn down an offer of $7,000 to go to Africa to write a film script, I’m damned if I know. You must have more money than brains.”

October 9

BORN: 1899 Bruce Catton (A Stillness at Appomattox), Petoskey, Mich.

1934 Jill Ker Conway (The Road from Coorain), Hillston, Australia

DIED: 2003 Carolyn Heilbrun (Writing a Woman’s Life, Amanda Cross novels), 77, New York City

2004 Jacques Derrida (Of Grammatology), 74, Paris

1849 Rarely has the choice of a literary executor been so poorly made as when Edgar Allan Poe, ailing at age forty, asked a fellow editor—and sometimes rival—named Rufus W. Griswold to oversee the publication of his works after his death. When Poe died in a delirium a few months later, Griswold fulfilled his obligation by publishing a vicious obituary in the New York Tribune on this day that portrayed Poe as a talented but friendless madman whose death no one mourned. The following year, he continued his attack with an edition of Poe’s works in which he made up scurrilous quotes from Poe’s unpublished letters and falsely claimed the late author had plagiarized, been expelled from college, deserted the army, and seduced his stepmother, a portrait that became the dominant image of Poe for decades to come.

1890 The trouble with fictional chronologies is that sometimes the math just doesn’t add up. It sharpens our sense of Sherlock Holmes as a living presence to read such concrete details as the posted notice in one of his best-loved cases that “THE RED-HEADED LEAGUE IS DISSOLVED, October 9, 1890.” The problem, though, as generations of Holmesians have debated, is that Mr. Jabez Wilson, the red-headed dupe of the tale, says he only worked at the league for two months before it mysteriously dissolved, but also that he began there in April (six months before October). How to account for the discrepancy? Rather than blaming sloppy storytelling by Watson or his creator Arthur Conan Doyle, some imaginative readers like Brad Keefauver have credited it to a clumsy attempt by Wilson to hide the amount he earned at the league, in hopes of lowering the fee he’d owe Holmes.

1899 “With this pencil I wrote the MS. of ‘The Emerald City.’ Finished Oct. 9th, 1899.” “The Emerald City” wasn’t the only title L. Frank Baum considered for his manuscript—he tried “The Land of Oz,” “From Kansas to Fairyland,” and “The City of the Great Oz” before settling on The Wonderful Wizard of Oz—but he felt strongly enough he had created something memorable that he framed the message above, along with the pencil. The month before Oz was published, Baum told his brother it was “the best thing I ever have written” and that his publisher expected to sell a quarter of a million copies. Although Oz didn’t match the sales of Baum’s earlier Father Goose before his publisher went bankrupt in 1902, by the time its copyright expired in 1956 there were four million copies of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz in print.

October 10

BORN: 1950 Nora Roberts (Angels Fall, Naked in Death), Silver Spring, Md.

1959 Jaime Hernandez (Love and Rockets, Locas), Oxnard, Calif.

DIED: 1837 Charles Fourier (The Theory of the Four Movements), 65, Paris

1973 Ludwig von Mises (The Theory of Money and Credit), 92, New York City

1914 “Married life really is the greatest institution that ever was,” P. G. Wodehouse declared ten days after his wedding. “When I look back and think of the rotten time I have been having all my life, compared with this, it makes me sick.”

1939 George Orwell harvested five eggs from his hens and made two pounds of blackberry jelly.

1947 Fired as a publisher’s assistant, William Styron reported to his father he was glad, since publishing is “only a counterfeit, a reflection, of really creative work.”

1947 Edith Sitwell, in the Spectator, on Northrop Frye’s Fearful Symmetry: A Study of William Blake: “To say it is a magnificent, extraordinary book is to praise it as it should be praised, but in doing so one gives little idea of the huge scope of the book and of its fiery understanding.”

1986 J. D. Salinger had refused requests for an interview for over twenty years, since ending his publishing career and removing himself from the public eye in 1965, but on this day he submitted to one, under duress, at the Manhattan offices of his attorney at the Satterlee Stephens law firm. His interviewer was a lawyer representing Random House and its author Ian Hamilton, whose forthcoming biography of Salinger used quotations from his personal letters that Salinger objected to strongly enough that he was willing to sit through a deposition. The process was, by all accounts, excruciating, as the lawyer extracted from the reclusive author a description of what he had been writing since 1965—“Just a work of fiction. That’s all.”—and for hours walked him through the nearly one hundred letters Hamilton had quoted, which Salinger said were written by a “gauche” and “callow” young man he could hardly recognize.

2006 At the center of Anthony Swofford’s third book, Hotels, Hospitals, and Jails, is a remarkable document, an eight-page handwritten letter from his father carrying six dates of composition between July and October and a final message added on this day: “I have sat on this for much too long . . . It is well past time to shred or mail. So mail here it comes. With Love, Your Father.” And so it came: a bill of grievances both petty and substantial, each with an accounting at the end: “You get a pass on that” or “No pass here.” And while Swofford’s book, Hotels, Hospitals, and Jails, is in part a raw confession of his self-destructive misbehavior after his first book, Jarhead, made him rich and famous, it is also a bill of grievances of his own, a book-length reply to his father’s letter that he feels he has to write before becoming a father himself.

October 11

BORN: 1925 Elmore Leonard (Hombre, Rum Punch, Out of Sight), New Orleans

1962 Anne Enright (The Gathering, What Are You Like?), Dublin

DIED: 1809 Meriwether Lewis (The Journals of Lewis and Clark), 35, Hohenwald, Tenn.

1963 Jean Cocteau (The Holy Terrors), 74, Milly-la-Forêt, France

1843 “Began the Chinese tale,” Hans Christian Andersen noted tersely in his diary on this day. By the next evening he had finished “The Nightingale,” the story of a songbird whose voice is so beautiful it draws death away from the dying emperor, a tale whose inspiration he’d recorded just a month before in the same diary, and with equal concision. “Jenny Lind’s first performance as Alice,” he wrote of the young singer already stirring a frenzy as the “Swedish Nightingale.” “In love.” He spent nearly all of the next ten days with her, giving her poems, a portrait of himself, a briefcase, and, just as she was leaving town, most likely a marriage proposal. She didn’t accept the latter, remaining friends with Andersen for the rest of their lives but always being careful to refer to them as “brother” and “sister.”

1928 Arthur Sydney McDowell, in the TLS, on Virginia Woolf’s Orlando: “It is a fantasy, impossible but delicious; existing in its own right by the colour of imagination and an exuberance of life and wit.”

1947 Published: Se questo è un uomo (If This Is a Man/Survival in Auschwitz) by Primo Levi (De Silva, Turin)

1949 Richard Wright had fielded offers before to turn Native Son into a movie (MGM, astoundingly, had once been interested in filming it with an all-white cast), but when French director Pierre Chenal suggested making the movie in Argentina, he accepted. But who would play the lead role of Bigger Thomas? Wright suggested Canada Lee, a sensation in Orson Welles’s stage version, but Chenal had an improbable idea: why not Wright himself? Even more improbably, Wright took the role, and on this day, having trimmed twenty-five pounds on the voyage, he arrived in Buenos Aires to begin shooting what they hoped would be the biggest movie ever made in South America. Acclaimed in Argentina, the film was panned after being chopped by a third for U.S. and European distribution.

2007 Greeted by reporters on her London doorstep with the news that she had won the Nobel Prize for Literature at age eighty-seven, Doris Lessing put her grocery bags down and sighed, “Oh, Christ.”

October 12

BORN: 1939 James Crumley (The Last Good Kiss), Three Rivers, Tex.

1949 Richard Price (Clockers, Lush Life), Bronx, N.Y.

DIED: 1926 Edwin A. Abbott (Flatland), 87, London

2010 Belva Plain (Evergreen, Promises), 95, Short Hills, N.J.

1713 Surely it’s no coincidence that Neal Stephenson’s Baroque Cycle, his three-volume, nearly 3,000-page epic of the Age of Enlightenment, begins on this day with the execution of a witch: the triumph of rationality is never a sure, or linear, outcome. On the same day, Enoch Root arrives at the bustling frontier outpost of Boston to deliver a letter to one of its many immigrants, Daniel Waterhouse. Waterhouse, once a friend of both Newton and Leibniz and now the founder of a misbegotten academy, the Massachusetts Bay Colony Institute of Technologickal Arts, has been summoned back to Europe to mediate the supremely irrational dispute between the two inventors of the calculus and thereby rescue the path toward progress that Root promises, with Stephenson’s usual brand of anachronistic cheek, will ultimately make Waterhouse’s own institute a glorious campus dedicated to the “art of automatic computing.”

1927 Edith Wharton married Teddy Wharton and had her most passionate affair with Morton Fullerton, but it was about Walter Van Rensselaer Berry that she wrote in her diary after his death, “The Love of all my life died today, & I with him.” Berry had not taken either of his two clear opportunities to propose to her, once when they first met in Maine in their youth and once after she finally divorced the miserable Teddy twenty years later, but they were close allies in public and private for the second half of her life. The social columnists considered him the model for Selden in The House of Mirth, and her friends assumed they were lovers, but her biographers have been less sure, in part because she got into his apartment soon after his death and burned nearly all the letters she’d written him.

1961 The loudest explosion in the salvo of contempt that greeted the publication of Webster’s Third New International Dictionary was launched from the heights of the New York Times editorial page. Mocking the Webster’s lexicographers with some of their own approved language as “double-domes” who “have been confabbing and yakking for twenty-seven years,” the Times called for a return to the old Webster’s Second. Outrage against the Third’s “permissiveness” became infectious: critics misled by the dictionary’s own press release knocked it for okaying slang with headlines like “Saying Ain’t Ain’t Wrong,” Dwight Macdonald published a twenty-page takedown of the dictionary in The New Yorker, and in Gambit Rex Stout had his fastidious sleuth Nero Wolfe feed pages from the Third into the fire.

1979 Published: The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy by Douglas Adams (Arthur Barker, London)

October 13

BORN: 1890 Conrad Richter (The Light in the Forest), Pine Grove, Pa.

1902 Arna Bontemps (Black Thunder), Alexandria, La.

DIED: 1995 Henry Roth (Call It Sleep), 89, Albuquerque, N.M.

2002 Stephen E. Ambrose (Undaunted Courage), 66, Bay St. Louis, Miss.

1819 John Keats, twenty-three, was already ill with the tuberculosis that would kill him less than two years later when his love for the young Fanny Brawne reached its feverish height. On this day, in a dash-filled letter, he struggled to find a language for his passion: “I have been astonished that Men could die Martyrs for religion—I have shudder’d at it—I shudder no more—I could be martyr’d for my Religion—Love is my religion—I could die for that—I could die for you.” A few days later, it is thought, he gave her a ring to seal their secret engagement. It’s also speculated that this was the same week he found a more disciplined language for his love in the sonnet that begins “Bright star! would I were steadfast as thou art,” which for two centuries since has set its readers to swooning.

1926 “We have so many bedbugs,” Isaac Babel wrote his mother from Moscow, “that it has become a legend among the other dwellers in our apartment.”

1958 At a Buddhist temple on the Upper West Side on this day, as described in How I Became Hettie Jones, her memoir of bohemian life among the Beats, Hettie Cohen became Hettie Jones, marrying LeRoi Jones, a poet she’d met when they both worked for a small Greenwich Village magazine for record collectors. Her husband would later change his own name, to Amiri Baraka, when he moved to Harlem in 1965 and helped launch the Black Arts movement, while Hettie Jones (whom Baraka, to add to the confusion of names, called “Nellie Kohn” in his own memoir, The Autobiography of LeRoi Jones) stayed in lower Manhattan with their two daughters and remained Hettie Jones.

1958 Published: A Bear Called Paddington by Michael Bond (Collins, London)

1997 David Foster Wallace, in the New York Observer, on John Updike’s Toward the End of Time: “A novel so mind-bendingly clunky and self-indulgent that it’s hard to believe the author let it be published in this kind of shape.”

2001 Chided again by critic James Wood for the “hysterical realism” he said her fiction shared with DeLillo, Rushdie, Wallace, and others, Zadie Smith wryly admitted in the Guardian that although in her first novel she may have aspired to the spareness of Kafka, she “wrote like a script editor for The Simpsons who’d briefly joined a religious cult and then discovered Foucault. Such is life.” Now, though, in the weeks after September 11, she added, she was “sitting here in my pants, looking at a blank screen, finding nothing funny, scared out of my mind like everybody else.”

October 14

BORN: 1894 E. E. Cummings (The Enormous Room), Cambridge, Mass.

1942 Péter Nádas (A Book of Memories), Budapest

DIED: 1959 Errol Flynn (My Wicked, Wicked Ways), 50, Vancouver, B.C.

1997 Harold Robbins (The Carpetbaggers), 81, Palm Springs, Calif.

1667 Having been expelled from his Jewish community in Amsterdam in 1656 for his heretical teachings, the philosopher Baruch Spinoza taught himself to grind lenses, a craft of newfound interest in that age of explorations with the telescope and the microscope, and one in keeping with his radical belief in a God of nature, not of man. Over time, his skills increased to where his fame as a lens grinder approached his infamy as the “atheist Jew”; in a letter on this day, Christiaan Huygens, the discoverer of Saturn’s moon Titan, praised the lenses of “the Jew of Voorburg” for their “admirable polish.” Over time, however, the grinding may have also hastened Spinoza’s death from a lung disease often blamed on the glass dust he inhaled every day.

1939 Ambitious and prolific, Thomas Merton spent his twenty-fifth summer with two friends in a cottage in upstate New York, each writing a novel he thought would make his name. Back in New York City in the fall, Merton got a publisher’s rejection slip for his novel on this day; when he called to ask why, they said it was dull and badly written, and Merton realized he agreed. But by that time his mind had moved on to other things: in a jazz club that same month, disgusted with his life, he realized he wanted to become a priest. A decade later he told the story of his awakening in The Seven Storey Mountain, a memoir written from his new life in a Trappist monastery that, neither dull nor badly written, became an immediate bestseller and a Catholic touchstone.

1972 The New Republic on Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: “This is more hype than book. It needs some humanity and a better idea of what time it is.”

1994 As he did every Friday afternoon for years, Naguib Mahfouz, frail and nearly blind and deaf at age eighty-two, crossed from his apartment to the waiting car of a friend who would drive him to a café for his weekly meeting with other Cairo writers and intellectuals. From the sidewalk a young man greeted him, as many did, but when Mahfouz reached out through the open car window to shake his hand, the man stabbed him in the neck. The attack, which Mahfouz outlived by a dozen years, came on the sixth anniversary of his Nobel Prize for Literature—the first for an Arabic writer—but what was the cause? Mahfouz’s condemnation of the fatwa against Salman Rushdie for The Satanic Verses, or his own controversial religious allegory, Children of Gebelaawi, which had been judged heretical and banned in Egypt thirty-five years before?

October 15

BORN: 1844 Friedrich Nietzsche (Thus Spoke Zarathustra), Röcken, Prussia

1881 P. G. Wodehouse (Carry On, Jeeves), Guildford, England

1923 Italo Calvino (Invisible Cities), Santiago de las Vegas, Cuba

DIED: 1968 Virginia Lee Burton (Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel), 59, Boston

1764 By his own account, Edward Gibbon, on his first visit to the Eternal City, was inspired to write The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire by the presence of its glorious but deteriorating past: “It was at Rome on the fifteenth of October 1764, as I sat musing amidst the ruins of the Capitol while the barefooted fryars were singing Vespers in the temple of Jupiter, that the idea of writing the decline and fall of the City first started to my mind.” Some later historians have been skeptical of the exactness of this memory, which he didn’t describe until thirty years later, but few were skeptical of the Decline and Fall itself, whose innovative use of primary sources created the standard for modern history.

1920 Katherine Mansfield, in the Athenaeum, on Gertrude Stein’s Three Lives: “Miss Gertrude Stein has discovered a new way of writing stories. It is just to keep right on writing them. Don’t mind how often you go back to the beginning, don’t hesitate to say the same thing over and over again—people are always repeating themselves—don’t be put off if the words sound funny at times: just keep right on, and by the time you’ve done writing you’ll have produced your effect.”

1967 The standing ovation Richard Burton received when he read from David Jones’s In Parenthesis on the same stage as W. H. Auden left Auden with, at least according to Burton’s diary, a “ghostly smile” and a look of “surprise, malice, and envy.”

1976 Among the things Eleanor Coppola took note of on this day while her husband, Francis, was shooting thirty-eight takes of a scene at Colonel Kurtz’s compound for Apocalypse Now: the severed heads played by local people, who were buried in the ground all day, drinking Cokes; a man giving a boa constrictor a sip of water; fake blood being used up fast at $35 a gallon; kids “putting chunks of dry ice in film cans and making the lids pop off.” Coppola was on set in the Philippines to shoot a documentary about the making of the picture; the documentary, the wonderful Hearts of Darkness, wasn’t released until 1991, but her diary of the production, Notes, was published in 1979, the same year the movie came out, and it’s a calm and observant record of a tumultuous experience.

2012 James Wood, in The New Yorker, on Tom Wolfe’s Back to Blood: “In the regime of the enforced exclamation mark, everyone is equal.”

October 16

BORN: 1854 Oscar Wilde (The Picture of Dorian Gray), Dublin

1888 Eugene O’Neill (A Long Day’s Journey into Night), New York City

DIED: 1997 James A. Michener (Hawaii, Chesapeake, Space), 90, Austin, Tex.

1999 Jean Shepherd (In God We Trust, All Others Pay Cash), 78, Sanibel Island, Fla.

1892 The New York Times on Arthur Conan Doyle’s Adventures of Sherlock Holmes: “You may care for one detective story, but when there is a round dozen you may get a fit of indigestion . . . Sherlock Holmes, with all his mise en scène, has too much of premeditation about him. You weary of his perspicacity.”

1933 Evicted from her Florida apartment for unpaid back rent of $18, Zora Neale Hurston received a wire from Lippincott offering her a $200 advance for her first novel, Jonah’s Gourd Vine: “I never expect to have a greater thrill than that wire gave me. You know the feeling when you found your first pubic hair. Greater than that.”

1935 Dismissed on this day by the Nazi regime from his position at the University of Marburg because he was a Jew, Erich Auerbach arranged to resume his career in exile at Istanbul University, where he continued his labors on one of the monumental works of literary analysis, Mimesis, an imaginative and approachable multilingual survey of the literary representation of reality from Dante to Virginia Woolf. His achievement was only made more impressive by his distance from the usual reference materials he would have had in Europe, a condition he modestly deflected in his epilogue to the book: “If it had been possible for me to acquaint myself with all the work that has been done on so many subjects, I might have never reached the point of writing.”

1952 To his son in Rome, spending a year in residence at the American Academy, William Styron Sr. wrote, “Son, don’t eat so much Italian food that you will grow gross and heavy like Thomas Wolfe. Extra weight certainly shortens our lives.”

1961 Published: Mastering the Art of French Cooking, vol. 1, by Simone Beck, Louisette Bertholle, and Julia Child (Knopf, New York)

1995 However many men there actually were at the Million Man March at the National Mall in 1995, we only see a handful of them in Z. Z. Packer’s story “An Ant of the Self” in Drinking Coffee Elsewhere, and we only learn the names of two: Ray Bivens Jr. and his son, Spurgeon, who are there on an ill-fated mission to sell some black men some birds. Spurgeon—“nerdy ol’ Spurgeon”—can’t explain what makes him skip his debate tournament to drive his dad to D.C. in his mom’s car after bailing him out of a DUI, nor can he explain what drives him into a bloody battle with Ray Jr. on a suburban sidewalk in the middle of the night after the march, but there’s something in him, alongside his ambition, that wants to know the feeling of scraping bottom.

October 17

BORN: 1903 Nathanael West (Miss Lonelyhearts, The Day of the Locust), New York City

1915 Arthur Miller (Death of a Salesman, The Crucible), New York City

DIED: 1973 Ingeborg Bachmann (Malina, The Book of Franza), 47, Rome

1979 S. J. Perelman (Crazy Like a Fox, Westward Ha!), 75, New York City

1861 E. S. Dennis, in the Times, on Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations: “Faults there are in abundance, but who is going to find fault when the very essence of the fun is to commit faults?”

1945 On this day Ava Gardner became the fifth wife of the clarinet-playing lothario Artie Shaw, who put the starlet on a reading program so she might be worthy of the frequently bestowed title of “Mrs. Artie Shaw”: The Brothers Karamazov, Babbitt, Tropic of Cancer, The Origin of Species. But he’d deny the story Gardner later loved to tell, that he mocked her when he caught her reading Kathleen Winsor’s bodice-ripping bestseller Forever Amber. No doubt Gardner liked to tell it because just a few days after Shaw divorced her, he rushed down to Mexico, where Kathleen Winsor herself, sultry enough that some thought she should star in the movie of her own book, became Mrs. Artie Shaw number six.

1964 It was with great relief that Richard Hughes confirmed to his publisher on this day, after a visit to the Pinewood Studios, that “John does break his neck . . . , Emily does murder the prisoner and does bring the pirates to the gallows.” Hughes’s A High Wind in Jamaica, one of the strange and great novels of the century, had long drawn interest from movie producers, but only in 1964 did a big-budget production commence, starring Anthony Quinn and James Coburn as pirates and, as the doomed John, one of the children who prove more terrible than their pirate captors, a child actor in his only film role, the future novelist Martin Amis, who later recalled that the visiting author was “pleased, impressed, tickled” by the production, as well as “otiously tall.”

1969 “The plain fact is, Mr. Hayes, I have earned this job—through great love of the short story and great labor to know it.” Gordon Lish was thirty-five, a frustrated and restless textbook editor, when he heard that one of the biggest jobs in his little business, fiction editor at Esquire, was open. “I want this job,” he declared in a long letter to editor in chief Harold Hayes, “and I want it with more eagerness than is becoming to a man of my age because this is the work I was meant to do, and because I have not been doing it.” Esquire took a chance on him and for the next seven years, calling himself “Captain Fiction,” Lish championed new writers like Barry Hannah, Richard Ford, and his old friend Raymond Carver.

1978 “The evidence of copying,” expert witness Michael Wood testified in the trial of whether Alex Haley had plagiarized portions of Roots from Harold Courlander’s The African, “is clear and irrefutable.”

October 18

BORN: 1777 Heinrich von Kleist (The Marquise of O—), Frankfurt, Germany

1948 Ntozake Shange (For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow Is Enuf), Trenton, N.J.

DIED: 1973 Walt Kelly (Pogo), 60, Woodland Hills, Calif.

1973 Leo Strauss (Natural Right and History), 74, Annapolis, Md.

1831 Alexis de Tocqueville, living on “Street No. 3” while visiting Philadelphia, found the regularity of the city’s design “tiresome but convenient.” “Don’t you find that only a people whose imagination is frozen could invent such a system?” he asked. “These people here know only arithmetic.”

1859 Nine years after she stayed with the Swiss painter François d’Albert Durade while depressed after her father’s death, George Eliot wrote to him of her success as a novelist, so he could know “that one whom you knew when she was not very happy and when her life seemed to serve no purpose of much worth, has been at last blessed with the sense that she has done something worth living and suffering for.”

1917 Virginia Woolf, in the TLS, on Henry James’s last memoir, The Middle Years: “He comes to his task with an indescribable air of one so charged and laden with precious stuff that he hardly knows how to divest himself of it all.”

1921 Through six years in an orphanage, six more as a hobo, ten years as a traveling tree surgeon, and dozens of bouts as a professional featherweight, Jim Tully most wanted to be a writer, and finally, at the age of thirty-five, he received a telegram from Harcourt, Brace accepting his first novel, Emmett Lawler, launching one of the most unlikely literary careers of the century. His next book, Beggars of Life, became a bestselling hobo classic, while Tully, charming and pugnacious at five foot three, became the toast of Hollywood. Admired by Mencken, employed by Chaplin, and befriended by Jack Dempsey and W. C. Fields, he knocked out matinee idol John Gilbert with one punch and then costarred with him in Way for a Sailor before his career flamed out in the thirties and left him forgotten by the fifties.

1980 At first he was described only as “a free-lance writer named Bill,” one of the Kansas City locals who joined Roger Angell after the fourth game of the Royals-Phillies World Series for a dinner of ribs and baseball talk that Angell distilled, in his lyrical way, into a “murmurous Missouri of baseball memories” in The New Yorker. But by the time the essay reappeared in Angell’s Late Innings two years later, “Bill” was further identified as “Bill James, a lanky, bearded, thirty-two-year-old baseball scholar who writes the invaluable Baseball Abstract.” By then Daniel Okrent’s profile of James in Sports Illustrated had made him nearly famous; by the end of the century, his iconoclastic statistical theories made him one of the most influential figures in the sport.

October 19

BORN: 1931 John le Carré (Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy), Poole, England

1938 Renata Adler (Speedboat, Reckless Disregard), Milan, Italy

DIED: 1682 Thomas Browne (Religio Medici, Urn Burial), 77, Norwich, England

1745 Jonathan Swift (Gulliver’s Travels, A Modest Proposal), 77, Dublin

1908 Before there was a Macondo, the legendary setting of One Hundred Years of Solitude, there was Aracataca, the remote Colombian town where Gabriel García Márquez was born, and where his maternal grandfather, Colonel Nicolás Márquez, loomed as its leading citizen. And before Aracataca there was the dark moment in the family history, when Colonel Márquez killed another man in a “matter of honor” in a manner that may or may not have been honorable. The details were hazy—was his victim armed or not?—but the outcome was clear: the colonel was forced to leave town and make his fortune on the other side of the mountains. For the young novelist, given puzzling pieces of the story as a child, it was “the first incident from real life that stirred my writer’s instincts,” and one he was never “able to exorcise,” even after he transformed it, in One Hundred Years of Solitude, into the moment when José Arcadio Buendía hurls a spear “with the strength of a bull” into the neck of his rival.

1970 When Donald Goines was released from Jackson State Penitentiary in December 1970 after a stint for attempted larceny—following ones for armed robbery, abetting prostitution, and the unlicensed distilling of whiskey—he left with the manuscript of a novel and a contract for its publication, signed on this day. Inspired by the underworld stories of Iceberg Slim, Goines had signed with Slim’s Los Angeles publisher, Holloway House, who released Dopefiend and Whoreson, the first two novels in Goines’s short but prolific career as one of the pioneers of street fiction. Murdered in Detroit in 1974, Goines was rediscovered thirty years later by a new generation of hip-hop artists, with movies based on his works starring DMX, Ice-T, and Snoop Dogg.

1988 Three years after a forced marriage between two corporate titans, R. J. Reynolds and Nabisco, created RJR Nabisco, it was clear the awkward alliance between cigarettes and Oreos wasn’t taking, and Russ Johnson, the company’s flamboyant, mop-headed CEO, had an idea: a leveraged buyout that would split the two companies and, by the way, allow management to reap an obscene windfall. He sold his board on the plan at a meeting on this day, kicking off the greatest corporate frenzy of the go-go ’80s, a bidding war that nearly tripled the company’s stock price in six weeks and provided the dramatic material for one of the iconic narratives of the decade, Bryan Burrough and John Helyar’s Barbarians at the Gate.

October 20

BORN: 1854 Arthur Rimbaud (A Season in Hell), Charleville, France

1946 Elfriede Jelinek (The Piano Teacher), Mürzzuschlag, Austria

DIED: 1890 Richard Francis Burton (The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night), 69, Trieste

1994 Francis Steegmuller (Flaubert and Madame Bovary), 88, Naples, Italy

NO YEAR “Enough,” the groom declares. “There will be no wedding to-day.” The wedding is off, in this quiet country church, because a stranger has stepped forward to testify that on October 20, fifteen years before, the groom, Edward Fairfax Rochester of Thornfield Hall, married Bertha Antoinetta Mason in Spanish Town, Jamaica, and that Mrs. Bertha Rochester is still alive. In fact, she resides in, of all places, Thornfield Hall, and Rochester’s thwarted second bride, Jane Eyre, is about to be introduced to her. Charlotte Brontë said little more about this earlier marriage in Jane Eyre, but in Wide Sargasso Sea Jean Rhys imagined the story of the first Mrs. Rochester and their doomed wedding, which in her telling Rochester greets with the words “So it was all over.”

1854 Not long after their honeymoon, Brontë’s new husband, the Reverend Arthur Bell Nicholls, took hold of the reins of her correspondence, telling his wife that letters like hers, which comment so freely about their acquaintances, “are dangerous as lucifer matches.” She must refrain from writing her opinions to her good friend Ellen Nussey, he declared, or Ellen must burn her letters after reading. For the good fortune of later readers, neither woman obeyed, allowing us to read, among other things, Charlotte’s comments about Arthur himself: “Men don’t seem to understand making letters a vehicle of communication—they always seem to think us incautious . . . I can’t help laughing—this seems to me so funny. Arthur however says he is quite ‘serious’ and looks it, I assure you—he is bending over the desk with his eyes full of concern.”

1962 During a cultural thaw that had just a few months remaining, Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev broke a decades-long taboo by approving the publication of One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, an unsparing novel by former prisoner Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn about the brutal life in one of Stalin’s labor camps. To those in the Politburo who feared its revelations about the camp, the premier retorted, as he proudly recounted on this day to Solzhenitsyn’s editor, “What do you think it was, a holiday resort?” The novel was an immediate success in the USSR and in the West, but within two years Khrushchev was forced out of office by Brezhnev, within five Ivan Denisovich was quietly removed from Soviet libraries, and within twelve Solzhenitsyn himself was forcibly exiled to the West.

1973 John Updike, in The New Yorker, on Günter Grass’s From the Diary of a Snail: “Imaginations seem to be as choosy as mollusks about the soil they inhabit; amid a great deal of mental travelogue, this one episode dankly, grotesquely lives.”

October 21

BORN: 1772 Samuel Taylor Coleridge (“The Rime of the Ancient Mariner”), Ottery St. Mary, England

1929 Ursula K. Le Guin (A Wizard of Earthsea), Berkeley, Calif.

DIED: 1969 Jack Kerouac (The Dharma Bums), 47, St. Petersburg, Fla.

1974 Donald Goines (Dopefiend, Whoreson), 37, Detroit

1920 J. R. Ackerley’s My Father and Myself is a disarmingly frank memoir of a life—or rather two lives—of secrecy. Ackerley’s secrecy was forced on him—being a homosexual was a crime then in England—but in his writing he told all, both about his own life and what he learned of his father’s, a prosperous and respectable Edwardian who once hinted to his son that “in the matter of sex there was nothing he had not done, no experience he hadn’t tasted.” Only after his death was that revealed to include bigamy: he left his son two letters, the first dated on this day, that confessed he had a second family, including three children who knew him only as Uncle Bodger. “I’m not going to make any excuses, old man,” he added. Neither did his son.

1967 “How do you make a good movie in this country without being jumped on?” The critical tide had already turned in favor of Bonnie and Clyde when on this day The New Yorker published Pauline Kael’s 7,000-word defense of the movie, which began with the plea above. Lively and combative, Kael’s review ended up being an audition for the regular reviewing gig she kept at the magazine for the next twenty-three years. Meanwhile, in the New York Times, the movie and its stylish but unsettling violence forced the end of another career: Bosley Crowther’s tone-deaf campaign against the picture, which he called a “cheap piece of bald-faced slapstick comedy,” was the final straw that drove him out of the powerful reviewing chair he had held there for twenty-seven years.

1967 There is something of The Red Badge of Courage in The Armies of the Night, Norman Mailer’s autobiographical history-as-novel: the confused and comic figure muddling through the periphery of a mass event with little control over its outcome. In this case, though, it’s not a war the figure was muddling through but a protest against a war—the March on the Pentagon on this day—and the comic figure is Mailer, with a highly tuned sense of the absurd but also a drive to push to the center of things and make a spectacle of himself. The result is one of his best books: both grandiose and self-deflating, and attuned to the danger of something happening, or of nothing happening at all.

1990 Jay Parini, in the New York Times, on A. S. Byatt’s Possession: “A. S. Byatt is a writer in mid-career whose time has certainly come, because ‘Possession’ is a tour de force that opens every narrative device of English fiction to inspection without, for a moment, ceasing to delight.”

October 22

BORN: 1919 Doris Lessing (The Golden Notebook, The Four-Gated City), Kermanshah, Iran

1965 A. L. Kennedy (Paradise, On Bullfighting), Dundee, Scotland

DIED: 1982 Richard Hugo (The Real West Marginal Way), 58, Seattle

1998 Eric Ambler (Journey into Fear,

The Light of Day), 89, London

1942 Raymond Chandler was always touchy about how his books were talked about, especially when it came to James M. Cain, with whom Chandler and Dashiell Hammett were often lumped as “hard-boiled” writers. Hammett, he wrote his publisher Blanche Knopf on this day, was “all right,” but Cain? “He is every kind of writer I detest, a faux naif, a Proust in greasy overalls, a dirty little boy with a piece of chalk and a board fence and nobody looking . . . Do I, for God’s sake, sound like that?” Despite this disdain, within a year Chandler was under contract to sound like Cain, as the co-writer of Billy Wilder’s adaptation of Cain’s Double Indemnity, for which Chandler would share his first Academy Award nomination for best screenplay.

1961 Richard Stern, in the New York Times, on Catch-22: “Its author, Joseph Heller, is like a brilliant painter who decides to throw all the ideas in his sketchbooks onto one canvas, relying on their charm and shock to compensate for the lack of design.”

1962 Well into his last years of drunkenness, delusion, and lingering charisma, Delmore Schwartz read his poems at the first National Poetry Festival in Washington, D.C., in a tremulously declamatory voice. That evening he “hurt his hotel room” (in the words of Richard Wilbur) and was brought, raging, to a police station, where his release was arranged by Wilbur and John Berryman, whose waiting taxi Schwartz then rode off in alone. Later, his great friend Berryman recalled that night in grief—as well as Schwartz’s earlier years of “unstained promise”—in “Dream Song #149.”

1973 On a Himalayan slope in the morning sun, Peter Matthiessen glimpsed something “much too big for a red panda, too covert for a musk deer, too dark for wolf or leopard, and much quicker than a bear.” Was it, he wondered in The Snow Leopard, a yeti?

1996 Forty-two years to the day after seeing his first opera—Rigoletto—on his eleventh birthday in Tokyo, Japanese industrialist Katsumi Hosokawa attends another musical birthday celebration, a concert by his favorite soprano, Roxane Coss, that was organized to draw him, and his business, to an unnamed South American country. But just as a song ends, the lights are shut off, and the men with guns enter the room. In adapting the events of the Lima hostage crisis, in which Peruvian insurgents laid siege to a party at the Japanese embassy and held its guests hostage for four months, for her novel Bel Canto, Ann Patchett changed details large and small, reimagining the crisis as an ensemble piece in which captives and captors are brought together by the “beautiful singing” of the title before the siege’s violent end.

October 23

BORN: 1942 Michael Crichton (The Andromeda Strain, Jurassic Park), Chicago

1961 Laurie Halse Anderson (Speak, Chains, Wintergirls), Potsdam, N.Y.

DIED: 1939 Zane Grey (Riders of the Purple Sage), 67, Altadena, Calif.

1996 Diana Trilling (We Must March My Darlings), 91, New York City

1847 “I wish you had not sent me Jane Eyre,” William Makepeace Thackeray wrote to the book’s publishers a week after it was published under the pseudonym Currer Bell. “It interested me so much,” he added, “that I have lost (or won, if you like) a whole day in reading it at the busiest period, with the printers I know waiting for copy.” (They were waiting for the next installment of Vanity Fair, just then making Thackeray a literary celebrity as it was serialized in Punch.) “It is a woman’s writing, but whose?” he speculated. In turn, when the second edition of Jane Eyre appeared, Charlotte Brontë (still writing as Currer Bell) dedicated it to Thackeray, “who, to my thinking, comes before the great ones of society, much as the son of Imlah came before the throned Kings of Judah and Israel.”

1869 “I shall leave no memoirs,” promised Isidore Ducasse, and he kept his word. Few writers left less for biographers than Ducasse, who wrote for a short, furious time as the Comte de Lautréamont, died of unknown causes in Paris at twenty-four, and left behind a poetic novel, The Songs of Maldoror, later embraced by the Surrealists. Maldoror breathes fire, declaring that unless the reader is “as fierce as what he is reading,” “the deadly emanations of this book will dissolve his soul as water does sugar,” but Ducasse took a milder tone in a rare surviving letter to his publisher, in which he argued his works were moral and shouldn’t be censored: he “sings of despair only to cast down the reader and make him desire the good as the remedy.”

1975 Inside, issue 198 of Rolling Stone may have been full of news of George Harrison’s new record, Foghat’s fall tour, and an unknown band called Talking Heads whose lead singer “looks like the bastard offspring of an unthinkable union between Lou Reed and Ralph Nader,” but the front page had the scoop of the year. In “Tania’s World,” Howard Kohn and David Weir landed the story everyone wanted, an inside report on Patty Hearst, the heiress-turned-terrorist who had taken up arms with her kidnappers, the ragtag revolutionaries called the Symbionese Liberation Army. Hearst was arrested just before the article appeared, but “Tania’s World” gave the first glimpse into the deliciously mundane details—the anxious road trips, takeout hamburgers, pay-phone rendezvous, safe-house skinny-dipping, and copy-shop communiqués—of her fugitive days.

1992 John Sutherland, in the TLS, on Donna Tartt’s The Secret History: “It aims to be hypnotic and finally achieves something more like narcosis. Tartt might have been wise to show her manuscript to a ruthless editor as well as to her indulgent college friends.”

October 24

BORN: 1933 Norman Rush (Mating, Mortals, Whites), San Francisco

1969 Emma Donoghue (Room, Slammerkin), Dublin

DIED: 1970 Richard Hofstadter (The Paranoid Style in American Politics), 54, New York City

1992 Laurie Colwin (Home Cooking, A Big Storm Knocked It Over), 48, New York City

1911 Whether “unsuitable reading material” was really one of the causes of the wave of teen suicides that swept across Germany before the First World War, as some claimed at the time, Rudolf Ditzen, who had taken to calling himself Harry after The Picture of Dorian Gray, was drawn to a literary death, along with his friend Hanss Dietrich von Necker. At first the Leipzig teens planned that the one whose writing was judged inferior (by a third party) would be shot, but then they decided instead to stage a suicide pact as if it were a duel over a girl. Ditzen survived the shots, Necker didn’t, and on this day Ditzen was arrested for murder. The charges were dropped, but the scandal was still fresh enough that when he published his first novel after the war, he took a pen name, Hans Fallada, that he kept through his tormented but often successful career.

1962 On a fall night in Harlem, at the height of the Cuban Missile Crisis, James Brown recorded a show that turned him from a chitlin’-circuit headliner into a nationwide star. Live at the Apollo is the name of both the resulting record and a little book by Douglas Wolk about the record, one of the standout entries in the marvelous 33 1/3 series of books on individual albums. Cramming as much drama and abrupt intensity into his tiny book as Brown did into his thirty-one-minute LP, Wolk lovingly diagrams the intricate web of performers’ lives, R&B riffs, and hit recordings that put that single night’s performance into context and make even the most fleeting of pop pleasures seem full of meaning.

1992 At 11:00 p.m., James Frey, a recent graduate of local Denison University, was cited by Granville, Ohio, police for driving under the influence and driving without a license after he drove his tire up onto a curb. Five hours later, Frey was released and never jailed again, which means that, among other events described in his memoirs A Million Little Pieces and My Friend Leonard, he wasn’t beaten by Granville cops with billy clubs or charged with Attempted Incitement of a Riot and Felony Mayhem, he did not get hit in the back of the head with a metal tray on the first of his eighty-seven days in a county facility for violent and felonious offenders by a three-hundred-pound illiterate black man named Porterhouse, nor did he read Don Quixote, Leaves of Grass, and East of Eden to Porterhouse, nor did Porterhouse cry when Anatole betrayed Natasha in War and Peace, nor did Porterhouse sleep with War and Peace and cradle it as if it were his child.

October 25

BORN: 1941 Anne Tyler (The Accidental Tourist, Breathing Lessons), Minneapolis

1975 Zadie Smith (White Teeth, On Beauty, NW), London

DIED: 1400 Geoffrey Chaucer (The Canterbury Tales), c. 57, London

1989 Mary McCarthy (Memories of a Catholic Girlhood), 77, New York City

1851 The Athenaeum on Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick: An “ill-compounded mixture of romance and matter-of-fact . . . Mr. Melville has to thank himself only if his horrors and his heroics are flung aside by the general reader, as so much trash belonging to the worst school of Bedlam literature,—since he seems not so much unable to learn as disdainful of learning the craft of an artist.”

1859 George Eliot read Balzac’s Père Goriot, “a hateful book.”

1946 Did Ludwig Wittgenstein threaten Karl Popper with a poker the only time they met, at a session of the Cambridge Moral Science Club on this afternoon—or did the two philosophers even attack each other, as some rumors soon had it? A more interesting question, as David Edmonds and John Eidinow explain in their enlightening history of the incident, Wittgenstein’s Poker, was why the meeting exploded in undeniable hostility. The two men, both products of the cultural hothouse of Vienna, were spoiling for a fight: Wittgenstein impatient and exacting, engaged with puzzles of language and sure there were no other questions, and Popper certain that philosophy had an obligation to confront the political problems of the world, as he just had in The Open Society and Its Enemies, a defense of liberalism against the Fascism that had nearly consumed Europe.

1972 It was the lowest point in their Watergate investigation. Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein woke to find their latest Washington Post story, which tied Nixon aide H. R. Haldeman to the slush fund that paid the Watergate burglars, denied by their main source and the Post pilloried as reckless and partisan like never before. By the end of the day, which also included a meeting pitching their book proposal for All the President’s Men to their future publisher, the reporters were able to confirm that Haldeman did run the fund, but Deep Throat, Woodward’s best inside source, was still worried. The next time they met, Deep Throat growled they had set back their story by months: “You’ve got people feeling sorry for Haldeman. I didn’t think that was possible.”

2012 Faulkner Literary Rights, LLC, filed suit in Mississippi against Sony Pictures Classics claiming that Owen Wilson’s paraphrase in Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris of two sentences from Requiem for a Nun—“The past is not dead! Actually, it’s not even past,” in Wilson’s version—violated the Faulkner estate’s copyright on the sentences.

October 26

BORN: 1902 Beryl Markham (West with the Night), Ashwell, England

1945 Pat Conroy (The Great Santini, The Prince of Tides), Atlanta

DIED: 1957 Nikos Kazantzakis (Zorba the Greek), 74, Freiburg, Germany

2008 Tony Hillerman (The Wailing Wind), 83, Albuquerque, N.M.

1726 Published: Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World by Lemuel Gulliver, later revealed as Jonathan Swift (Benjamin Motte, London)

1849 When the time came for Flaubert to set off with his friend Maxime Du Camp for his long-imagined trip to Greece and Egypt, he nearly balked at the idea of leaving his mother for the two-year journey. The day they parted was “atrocious,” “the worst I have ever spent”; finally he just kissed her and dashed away, listening to her screams from behind the door he shut behind him. After midnight he composed himself enough to write and send her a “thousand kisses,” and after he woke, on this day, he wrote again, saying, “I keep thinking of your sad face.” That evening, Du Camp returned to his Paris apartment to find his friend prostrate and sighing on the floor of his study. “Never again will I see my mother or my country! This journey is too long, too distant, it is tempting Providence! What madness!”