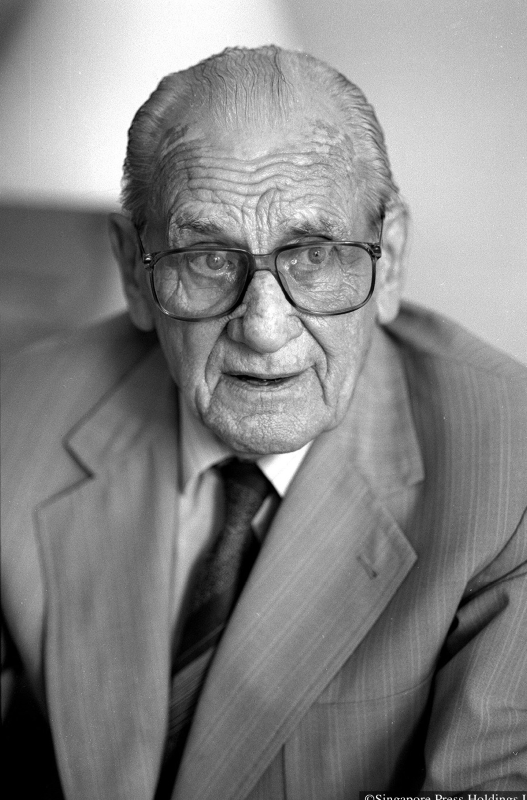

Albert Winsemius

A Nation’s Transformer

Singapore’s transformation from Third World to First would not have been possible without the foresight of Dutchman Albert Winsemius. His ideas—from developing labour-intensive industries to grooming more engineers and making the port profitable—were part of the blueprint for Singapore’s economic development. He offered his advice and ideas over 23 years without receiving a salary.

Looking at Singapore’s economic policies for the past few decades, one cannot help but feel that Albert Winsemius’ invisible hand is present in all of them. Reading his proposals for Singapore’s economic development in the 1961 Winsemius Report is akin to recollecting the country’s transformation from Third World to First.

Before coming to Singapore in October 1960, Winsemius, a Dutch economist, had not formulated any plans for it to develop its economy. What he did know about the island-state was based on newspaper articles and opinions he had picked up. These opinions were of the “accepted fact that Singapore was going down the drain”, he recounted in his oral history. He added, “Whether it was going down the drain or not, I did not know and didn’t want to know. I wanted to study it and try to give some advice, not to go down the drain, but to go the other way.”

Winsemius led the UN Industrial Survey Mission to examine Singapore’s potential for industrialisation. At Changi Airport, a journalist asked Winsemius, “Are you going to have contacts with the trade unions?” Winsemius replied, “Yes”, only to realise later that the trade unions and the government were going at one another head to head. In 1961, the country lost about 415,000 man-days in a year due to strikes and labour unrest. As Winsemius would later describe in a media interview, “It was bewildering. There were strikes about nothing.”

Singapore was then a city of some 2 million people, with a stagnant economy and an unemployment rate of around 14%. The report thus quickly identified industries, such as garment manufacturing, ship breaking and building materials, that required minimal state investment and could absorb many workers. Winsemius also gave two other recommendations. First, the government had to improve the dismal state of industrial relations. In 1961, Winsemius told Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew that the most urgent task was to “eliminate the communists…if you don’t do it, forget about economic development. They will try to destroy anything which can promote Singapore because they have intentions other than what you have.”

Winsemius had consulted widely, with bankers, diplomats and trade union leaders, when putting together his report. He remarked that trade union leaders like Lim Chin Siong and Fong Swee Suan possessed “high intellectual, often organisational, capacities”. Describing them as “communist leaders”, he said he never reached a point of “understanding or confidence” with them. He said, “The discussions were an intellectual fight and not more than that, not concentrated on: how can we develop Singapore, create work, work that was even more than pay.”

Second, Singapore had to keep the statue of Sir Stamford Raffles along the Singapore River. This would symbolise Singapore’s acceptance of its colonial heritage and demonstrate that it was open to foreign investment. Winsemius concluded that Singapore had the “basic assets” for industralisation, with its people having a high aptitude to work in manufacturing. The UN team had observed that there were many small enterprises already involved in the local manufacturing industry, though these companies lacked the resources and technology to scale up. The government, said the report, could operate certain basic industries if neither local nor foreign enterprise was prepared to do so, but it would need to do this in tune with commercial and market principles.

Winsemius also believed that Singapore needed a common market with the Federation of Malaya, where goods produced in one state or imported into it could move freely to other states without duties. This would benefit Singapore’s manufacturing sector, Winsemius believed, and could create 50,000 new jobs over 10 years. But the common market idea never materialised, even though Winsemius held on to it, suggesting in 1982 that Singapore would benefit from an ASEAN common market.

Winsemius accepted an offer to be the Singapore government’s chief economic adviser after he submitted his 1961 report. He held this position for 23 years before stepping down in 1984. During this time, he was “instrumental to the development of the ‘tripartite’ system, the establishment of the National Wages Council in 1972, and the wage adjustment policy [Singapore] adopted in the 1970s. He successfully advocated for the expansion of technical and scientific education and training in Singapore’s universities and polytechnics,” said former civil servant Ngiam Tong Dow, who was Winsemius’ liaison officer from the EDB.

Indeed, Winsemius’ recommendations were instrumental in Singapore’s economic development after its separation from Malaysia in 1965. The Dutchman advocated having better-trained and skilled manpower for high-end manufacturing. He went to Eindhoven to convince Dutch electronics giant Philips to invest in Singapore. He cautioned Philips that if they did not do so, they would “miss the boat in the growing market of Southeast Asia”. By the 1970s, Philips had set up television and audio production plants in Singapore.

Winsemius then suggested to the government that Singapore could be a global financial centre. It could fill a gap in the financial markets of the world. But this meant Singapore would have to face the prospect of delinking the dollar from the pound sterling. However, the matter resolved itself as the sterling area was dissolved in 1972. Winsemius also foresaw the need to develop Singapore into a centre of international traffic and cargo transport. He told the government to “build an airport where the biggest (airplanes) can land and let everyone know that they are welcome to land there”, and encouraged the development of a container harbour to tap into international trade flows.

Winsemius lived in The Hague during that period, and apart from visiting Singapore two to three times a year, he kept abreast of Singapore’s development via The Straits Times which was sent to him by airmail. He asked his grandson to help him track the quantity of job advertisements in the paper, as this, he believed, told him much more about the state of the economy than official statistics, recounted Ngiam, in a speech he gave in 2007.

For his contributions, Winsemius was given a series of honours, including the Distinguished Service Order in 1966. During the 23 years that he served the government, he was neither paid nor formally bound by a contract to work for Singapore. The collaboration was based on mutual trust. Winsemius had a good rapport with the late Prime Minister Lee and the late former EDB chief Dr Hon Sui Sen.

When Winsemius passed away in 1996, Lee’s eulogy read, “Singapore, and I personally, are indebted to him for the time, energy and devotion he gave to Singapore.” The ties between Winsemius and Singapore have continued. When Lee passed away in March 2015, Winsemius’ children, Pieter and Aeyelts, flew here to pay their respects.

References

“A Common Market will Create More Jobs,” The Straits Times, June 21, 1963.

Albert Winsemius, interview by Tan Kay Chee, August 30, 1982, accession number 000246, transcript, Oral History Centre, National Archives of Singapore.

Albert Winsemius, A Proposed Industrialization Programme for the State of Singapore

(Singapore: UN Commissioner for Technical Assistance, 1963).

Kees Tamboer, “Dr Albert Winsemius –Singapore’s Economic Engineer,” The Straits Times,

23 September 23, 1996.

Lee Kuan Yew, From Third World to First (Singapore: Singapore Press Holdings, 2000)

Low Mei Mei, “Roll of Honour,” The Straits Times, August 9, 1985.

Warren Fernandez, “Winsemsius-Wisdom Still Valid as S’pore Starts off on the Next Lap,”

The Straits Times, Aug 3, 1991.

UNDP Global Centre for Public Service Excellence, “UNDP and the making of Singapore’s Public Service—Lessons from Albert Winsemius,” accessed September 2015,

http://issuu.com/undppublicserv/docs/booklet_undp-sg50-winsemius_digital

Albert Winsemius

Netherlands, 1910–1996