QUESTION 2

HOW DID A PENAL COLONY CHANGE PEACEFULLY TO A DEMOCRACY?

The penal colony of New South Wales, established in 1788, became by 1860 a self-governing colony and a democracy, with all men having the right to vote. How did this amazing transformation happen? Some books do not pose this question at all; others give a variety of unconvincing answers, which mark the change rather than explain it.

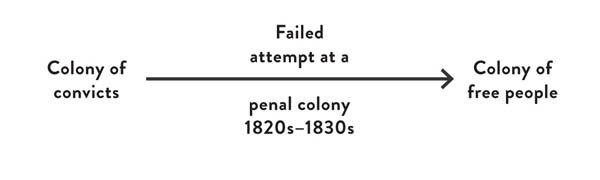

The vagueness and thinness of the answers arise because the question has been wrongly posed. New South Wales did not begin as a penal colony; it is better to think of it beginning as a colony of convicts. Its history can be represented in this way:

Why wasn’t early New South Wales a penal colony? The short answer is that British officials in 1786 could not conceive of such a beast: a society of warders and prisoners designed for punishment and control, as the French ran much later on Devil’s Island. In Britain in the eighteenth century there was no institutional treatment of convicted criminals; they were flogged or hanged or sent to the American colonies.

There were gaols but only for short-term imprisonment. They were prisons without prison discipline. There was a men’s ward and a women’s ward, and no bar to the men and women intermixing. One convict couple who came on the First Fleet had met and conceived a child in gaol. If you were a prisoner of some means you could send out for food and other comforts, and maybe pay the gaoler in order to occupy a room in his house. Running an institution without reference to the birth, wealth and connections of the inmates was unimaginable.

We can understand the mindset of the ministers and officials who established New South Wales by looking at what they planned when the convicts were to be sent to the west coast of Africa (a plan that was abandoned because the climate was too hostile).

The convicts were to be dumped on an island in the Gambia River and left to their own devices. They were to elect a chief and a council to make laws and administer the settlement. It was to be a little republic of convicts. They were to cultivate the ground to support themselves; at this, some would undoubtedly do better than others, and they would become employers of the rest. The British government would keep a ship at the mouth of the river to see that they did not escape. Clearly, ministers were not concerned to punish these men according to their crimes; the punishment was to be exile. The men most likely to emerge on top in this little republic would be the most hardened and enterprising offenders.

With New South Wales, the government was much more involved: there was a governor and a contingent of marines. But quite quickly this new settlement began to look something like a republic of convicts. On day one the marines went on strike: they refused to supervise the work of the convicts. They refused to supervise the convicts even when they were clearing the ground for the marines’ own tents. So Governor Phillip was forced to appoint convicts to oversee the work of other convicts. Their pay was the freedom not to work. The official rule was that convicts were to work from dawn to dusk, but the convict overseers soon adopted their own system to get work out of convicts. They fixed a daily task—so many trees felled; so much ground hoed—and when that was done the convicts were free to leave. If the convicts applied themselves, their task could be finished by midday.

This is how the convicts developed what they called their ‘own time’, which they defended ferociously. If the weather was bad in the morning and the government task could not be done, they refused to work for the government in the afternoon. In their ‘own time’ the convicts could laze about, steal, or take work and get paid for it.

It took years for governors to claim back at least some of the afternoon. The final rule was that the convicts had to stay at work either for the government or their private master until three o’clock. Governor Macquarie in 1814 declared that convicts had to work the full day for their private masters, but the masters had to pay for the work they did after three o’clock. This became known as their wage. For the convicts who worked for the government in Sydney, Macquarie built a barracks, which still stands in Macquarie Street. Once they had full board and lodging, the convicts did not need to earn money after three p.m. to pay for their private lodgings. But the convicts’ ‘own time’ was not forgotten; at weekends they were free to leave the barracks and live it up or work in the town.

In the second year at Sydney Cove, food supplies were shrinking and starvation loomed. Desperate to stop robberies, Phillip created a police force and had no choice but to staff it with convicts. These convicted felons were given authority over free men, the sailors and the marines; in particular, they were to detain any marines or sailors who were wandering around the camp at night.

Under these orders, the convict police did detain marines, but after several months the head of the military (and lieutenant governor), Major Robert Ross, raised a furious objection when a marine was detained. Phillip had trouble eliciting his reasons; he was almost apoplectic with rage and could only repeat that the power given to the convict police was an insult to his corps. Which, by all ordinary standards, it was. Phillip yielded so far as to alter the rules for the police so that they could detain marines only if they were actually committing a robbery. Then he sent Major Ross to take charge at Norfolk Island. The convict police remained.

Convict overseers and police: this was just the beginning. For all professional services, the governors drew on the convicts: lawyers, architects, surveyors, doctors, teachers, artists (who were former forgers). It was hard to get free people to come to the colony to do these tasks. The second governor, John Hunter, told the British government to stop looking for eligible free people; whatever he wanted doing, there was a convict who could do it. Free settlers also employed these convict professionals; a convict tutor was a regular feature of a gentleman’s home.

This so-called penal colony was run according to the principles of the ordinary English law. This was a late decision in the planning of the colony, taken, it seems, by Lord Sydney, the British home secretary, which is enough to warrant the immortality he has acquired through the city that bears his name. The first plan was for the colony to be governed under military law. The operation of the normal law meant that convicts could not receive any further punishment except by order of a court, and that before the court they appeared in the usual way, as innocents until proven guilty.

In fact, it became inadmissible to refer to a convict in court as a convict or ex-convict. In the magistrates’ court, where convicts were taken by their masters for offences against the labour code—being lazy, running away, getting drunk—they were unlikely to get off, though it was a great access to their dignity that their masters could not punish them themselves. Convicts did not work under the lash. For serious offences in the higher courts, the rate of acquittal was quite high—between a quarter and a third of all cases. The juries in these trials were six military or naval officers, who were partial when cases touching on their honour and interests arose, but otherwise were conscientious and willing to let a convict or ex-convict go free if the evidence against them was insufficient.

Convicts acquired more legal rights in the colony than they had at home. Convicts in England could not give evidence, own property or bring actions in court. Since in New South Wales most people were convicts, they had to be allowed to give evidence if the court was to learn what it needed to know about a case. Because convicts could testify, they could give evidence against their masters. Convicts also had to be considered as owners of property, otherwise other convicts could not be charged with pinching it. The first case in the criminal court concerned a convict who had stolen another convict’s bread ration.

If convicts were to protect their property, they had to be able to bring actions in court. The first case in the civil court was brought by a convict couple against the captain of the ship that had brought them to the colony. These were the convicts who had met in gaol, Henry Kable and Susannah Holmes. The government had at first planned to separate them, sending only Susannah and her baby to the colony. When the gaoler delivered Susannah and the baby to the ship, the captain refused to take the baby. The gaoler left Susannah at the ship and took the baby to London, where he camped outside the offices of Lord Sydney until he agreed that the baby and its mother and father could go to the new colony together. The case became famous and a fund was opened to equip the family for their new life. This was the baggage that the captain of the ship lost as they sailed to Australia. The court ruled that the captain had to pay the couple compensation.

The early governors were given no instructions as to the punishment of the convicts. The first job of the governors was survival; the second was economic growth, so that the colony could pay for itself. So they used the convicts according to their skills and diligence. They readily granted pardons to those who did good service, as well as to those who brought recommendations from home. The ‘ticket of leave’, which became a reward for good behaviour, was at first given to convicts who could get their own living and so be taken off the ration rolls. That reduced expenditure, which was what the British government was most concerned with.

Convicts had in this free-wheeling outfit plenty of opportunity to make money. The convicts who did best worked for the officers who had gone into the business of trading. Like all officers, they offset the tedium of a foreign posting by enriching themselves. They could import rum, tea, sugar and tobacco, but they could not actually set up a shop to sell them without damaging their claim to be gentlemen. The convict servants assigned to them ran the shops, and quite soon set themselves up in business on their own account, becoming traders, shipbuilders and bankers. These ex-convict businesspeople—men and women—were assigned convicts to work for them on the same terms as the officers and the few free settlers.

On becoming free, convicts were granted thirty acres as a farm and convict servants to help them work it. Few of the convicts were experienced or determined farmers. Most drank too much, fell into debt and sold off their lands, which were then bought by the more enterprising settlers, whether free or ex-convict. Some ex-convicts became wealthy landowners, but the route to this was in the first place through trade; starting with thirty acres was not the way fortunes were made.

Only one barrier was erected against the successful ex-convicts: no matter how much money they made, the officers and free settlers would not accept them as social equals. They did not expect to meet them at balls and dinners at Government House, which set the standards of ‘good society’. To modern Australians this seems snobbishness, but the other side of this social exclusion was economic opportunity: the officers and free settlers did not care what positions ex-convicts held or how much money they made because they would remain socially their inferiors.

Governor Macquarie thought the free settlers were always bitching, and that it was the ex-convicts who had made the place. He ‘went native’ and, fully accepting the logic of a convict republic, appointed three ex-convicts as magistrates; he invited them to Government House and expected the rest of the Government House crowd to accept them as equals. They deeply resented this, and this was one complaint that led to an official enquiry into the running of the colony. Macquarie was to be the last ruler of a colony of convicts.

But what about the floggings? This is what everyone knows about early New South Wales. There was a good deal of it. It was a regular punishment of the time used in the armed forces, the schools and the home. It is so obnoxious to us that it fosters misleading views of how the colony operated. When a flogging is depicted in film or on TV, a cruel, sneering free settler sends his convict off to the court for a trifling offence. The magistrate, who is a friend of the master, takes little time to convict him. The order of the court is that the man be flogged. There is a rattle of a drum; a small contingent of soldiers leads the culprit forth; an officer gives an order; the culprit is tied to the triangle; a soldier wields the whip.

This is entirely fanciful. The military had nothing to do with convict punishments. A convict or ex-convict policeman supervised the floggings, which were performed by a convict flogger. The convict could as well be sent for punishment by an ex-convict master. During the Macquarie madness, the magistrate might have been an ex-convict. That’s the picture to hold on to: an ex-convict master sends his convict to court; he is tried by an ex-convict magistrate; his punishment is supervised by an ex-convict policeman and he is flogged by a convict. Is this a penal colony? No, it’s a unique social formation.

New South Wales was entirely different from the penal settlements, properly called, that were established by the French in the 1850s in colonies that already existed, Guinea and New Caledonia. The warders and the prisoners were in a special separate settlement. The warders did their job—they kept the convicts to hard labour—and the convicts and their skills were not called on to secure survival. The settlements were all-male affairs. They did not have a transforming effect on the colonies in which they were placed.

It was, finally, the presence of women in New South Wales that makes ‘penal colony’ so inappropriate a term. The rulers of Britain were happy to hang and flog prisoners but they thought locking men away from female company for a long period was unnatural and cruel. So 191 women convicts were sent on the First Fleet to accompany the 568 men. Governor Phillip planned to bring other women from the Pacific islands to service the men, but once he arrived he decided that it would be unkind to bring them to a colony close to starvation.

Men and women together: this was a source of much disorder—and also of babies. There were babies conceived on the First Fleet. These infants were free British subjects. So before it began, this ‘penal colony’ was producing free people who grew up to call it home and thought of it as a nation in the making. Not even in its first year was this society composed just of convicts and their guards. In any case, the guards, as we have seen, were non-players in the penal department.

New South Wales was founded just as the cause of prison reform was taking off in Britain. The reformers wanted prisons to be well run, clean and healthy; the prisoners were to be classified, with men and women separated; and they were to be kept at work and attention given to their reformation. Solitary confinement was to be provided as a mode of punishment and an encouragement to reflection and reformation. When the reformers triumphed in the 1840s, solitary confinement was to be the lot of all prisoners. This was the terrible end point of a movement that thought of itself as humane and whose supporters worked as well on the abolition of slavery.

As these principles of punishment were accepted, New South Wales became a blot on the system. Here there was no classification, an indiscriminate mixing of the convicts, and no matching of punishment to crime or attempt at reformation. How could there be reformation when the convicts themselves composed almost the whole of the population? How could transportation be a deterrent when convicts lived well and some made fortunes? The reformers wanted transportation to New South Wales to be abandoned and all prisoners confined to prisons of the new type.

Building prisons according to the new principles was very expensive; expelling convicts out of the country was cheaper and psychologically very satisfying. Governments would not readily give up transportation but they had to take notice of the new principles. To this end, the government sent a commissioner of enquiry, John Bigge, to New South Wales in 1819. His brief was to find a way to make New South Wales a fit place for punishment, both for deterrence and reformation. After eighteen months of enquiry he produced his recommendations, which the British government adopted and Governors Brisbane (1821–1825) and Darling (1825–1831) carried out. This was the second stage in the colony’s history: the attempt to make it into a penal colony. How far was it successful?

In future, tickets of leave were to be given only to those who had been well behaved. Governor Macquarie had set rules so that convicts could not get a ticket until they had served a certain proportion of their sentence; seven-year men had to serve at least three years. But he had frequently broken his own rules, and the convicts, in their bolshie way, had come to assume they had a right to a ticket as soon as they had served the required time, no matter whether they had convictions for drunkenness or running away.

To ensure that each convict’s record could be known, there were now to be central records kept of all offences committed. This took some time to organise and the records were never perfect. They were much better in Tasmania, where on one page in the ‘Black Books’ all the details of the convict’s career were recorded. Most of the New South Wales records were destroyed; the Tasmanian records survive and are a wonderful resource for family historians.

So on this matter convicts were now handled in a bureaucratic way, with like cases treated alike—the same mindset from which came the notion of the well-ordered prison. The new system was a benefit to the convict who had no outstanding skill and no one to speak for him; if he kept his head down and did his work, he would get his ticket. Exceptions still had to be made: tickets were given out to those who caught bushrangers or gave useful information about the hard men and their plans, or agreed to go on an exploring expedition. And letters of recommendation from home could sometimes still get a result—an early ticket of leave. But the problem of what to do with gentlemen convicts was partly solved. A special settlement was created for them, but they were not to be put to ordinary labour; no one could contemplate that.

Convicts were no longer to receive a wage. But this did not mean that all convicts got their ration and nothing else. Skilled men would be given extra rations and the opportunity to do work in their own time and be paid for it, either by a master or a neighbouring settler. In 1833 the leader of one of the rare convict rebellions claimed in court that he and his fellow convicts had been repeatedly flogged and starved on the property of James Mudie in the Hunter Valley. Governor Bourke ordered an enquiry, which showed that these claims were untrue. It revealed that the leader of the rebellion, John Poole, was a carpenter in charge of a group of convicts who were building a windmill on the property. He got extra rations, including wine, and wore a white shirt. Mudie brought him a flute and a music book from Sydney. He got extra work making ploughs for other settlers. He got on well with Mudie but not with his son-in-law, who managed the property. When the son-in-law sent him to be flogged for insolence (his first flogging), Poole organised the revolt.

The food ration for convicts had been set down in London. It had been cut down in starvation time, restored and varied, but it survived as a standard that had to be met. It became the convict’s right to receive seven pounds of flour and seven pounds of meat per week. In 1823 this was abandoned and convicts were to receive what was ‘adequate’. About this there were many disputes. Convicts up on a charge of being lazy would claim they were being starved, and magistrates would have the difficult job of working out whether the food they received was ‘adequate’. Convicts thought anything other than white bread was definitely not adequate; they were not going to eat brown bread or maize meal. In 1831 the official ration was restored.

Regular and uniform discipline was now to operate in the places of secondary punishment. These were the settlements at Port Macquarie and Moreton Bay, where convicts who had committed serious offences in the colony were sent. They had been as lax as early New South Wales itself. The military ran their own farms and employed convicts on them. Friends of the convicts could send them food, clothing and other goods—free of carriage on the government supply boats—so convicts could run shops while they were being punished. Married convicts were allowed to have their wives and children join them, and they were allowed time off to work in their support. From the ranks of double-convicted prisoners, constables and over-seers were recruited. Now private farming and business were banned; all convicts had to be kept at hard work, with the hoe, not the plough, except that skilled men could work at their trades in cases of urgency—but only as a temporary measure. Well-behaved men could still have their wives join them. The overseers remained the convicts themselves.

In 1825 Norfolk Island was reopened. It had been an important adjunct to the early colony because it was so fertile, but it had not been used as a place of further punishment. Now it was to be a dreaded place of secondary punishment, the horror to keep men in order in New South Wales proper. Governor Darling ordered that no women were to be allowed, either wives of convicts or of soldiers. He acknowledged that the absence of women would lead to an increase in homosexuality, but he thought that the presence of a few women would not make much difference to its prevalence. In any case, his aim was deterrence; he didn’t mind how bad a place he created. Whether he was right about homosexuality or not, Darling correctly gauged the significance of barring women. He did not want the regularity of his prison disturbed by the comforting regularities of family life, or by the irregularities of the casual congress between men and women which had been part of life in every other settlement in New South Wales. Norfolk Island came closest to being a penal settlement, and could be so described if the convicts themselves were not the warders. Hated by the men as traitors and fearing always for the security of their jobs, they were the more tyrannical and cruel.

At Norfolk Island and at Port Arthur, in Tasmania, another place of secondary punishment, there are ruins of prisons built on the new principles of solitary confinement. At Port Arthur a wing of the separate prison has been restored, which includes the chapel where prisoners were seated in winged stalls to prevent them from seeing one another—so that solitary confinement would continue even in church. These relics are taken to be symbols of the convict system in Australia and its studied cruelty. They were actually built very late, to the formula of the British penal reformers who opposed transportation to Australia and the customary treatment of the convicts there. What was normal in the convict system has left no distinctive relics because most convicts saw out their time working for private masters, living in attics or separate kitchens, in the men’s huts at a sheep station or in a shepherd’s hut in the bush, or sharing bed and board with a small farmer.

That was the difficulty of running New South Wales proper according to penal principles. Private employers would never be concerned with punishment and reformation. They wanted to get work done, and they would cut deals and turn a blind eye as required. Bigge’s plan to forestall this criticism was that more free settlers should be encouraged to come to the colony. They would make better masters for convicts than the ex-convicts. If all convicts were sent to do hard work on their estates in the country, there would be consistency in punishment and more chance of reformation away from the fleshpots of Sydney. It was a neat solution but this part of Bigge’s report could not easily be implemented.

Four years after Bigge’s policy was adopted, the British colonial secretary told Governor Darling that there were still too many skilled convicts in Sydney. He wanted them sent to the country and put to hard labour. Darling explained that he could not obey this instruction: if he did, how would the various trades of Sydney—tailor, shoemaker, etc.—be carried on? The building workers were even more important; they worked for the government during the week and took private work at the weekend: ‘Thus has the Town of Sydney been built.’ These were very stubborn facts to be put against penal principles. Whitehall let the matter drop.

One further difficulty about arranging hard labour in the country was that, increasingly, the work was minding sheep (boring but not hard) or rounding up cattle (exciting, with the freedom of being mounted on horseback). As pastoralism spread beyond the boundaries, the men who owned the stock usually did not supervise the enterprise themselves. So convicts had overseers who were ex-convicts, ticket-of-leave men or even other convicts. This was not a recipe for good order and tight discipline. The perpetrators of the 1838 Myall Creek massacre, in which thirty Aborigines were slaughtered, were convict and ex-convict stockmen who had been roaming the district on horseback for days, looking for Aborigines to kill.

Better order could have been established over convicts, and better protection for the Aborigines provided, if the rush to new lands beyond the boundaries had been stopped. But the British government wanted the wool that the colony provided. A booming colonial economy trumped penal principles.

More free settlers with capital did arrive in the 1820s, and were allocated land and convicts to work it. The Hunter Valley, settled at this time, did develop as Bigge had wished. In other new areas some ex-convicts were among the pioneers, especially in cattle, which required less capital. Ex-convicts were strongest in trading, shops, pubs, farming and other small businesses. Overall, they employed about half of the convicts working for private masters. No one (not even Bigge) proposed that they should be deprived of their convict workers. To do so would have knocked out half the economy, something that would have damaged free settlers as well. Since ex-convicts were so well established so early, it would take a long time before the great majority of convicts had free settlers as masters.

A court ruling just before Bigge arrived in the colony had cast doubt on the legitimacy of the pardons the ex-convicts had received. If the pardons were doubtful, the next query might concern their capacity to hold property. Though Bigge doubted their quality as masters, he could see that the prosperity of the colony depended on the security of their property. He added his support to the petition already sent to Britain asking for the pardons to be validated by parliament. This was done in 1823. That gave the ex-convicts what the certificate of freedom (a local invention) had long claimed: that the holder was ‘restored to all the rights and privileges of free subjects’.

Overall, the changes made to the convict system following Bigge’s report fell a long way short of his plan for all the convicts to be working in the country under the supervision of respectable free settlers. That arrangement might warrant the title ‘penal colony’; I call the efforts made after his report a failed attempt at a penal colony. Too much could not be undone or bent to penal purposes.

*

The danger to New South Wales evolving into a free and democratic society came from the free settlers. If they had had their way, they would have made themselves into a ruling class and excluded the ex-convicts from power. The British government, which kept firm control over the colony, was the force that prevented this.

Britain was the pioneer liberal state. In the seventeenth century, parliament had tamed the monarchy by beheading one King and exiling another. The King still ruled but only parliament could pass laws and approve taxes. The King appointed judges but only parliament could dismiss them, an arrangement that established the law’s independence. That all Englishmen were entitled to the protection of the law, conducted without fear and favour, was a deeply entrenched belief. Only a few Englishmen voted, but all had the right to the security of their property and persons, and to be tried by a jury of their peers. This view was held strongly enough by Lord Sydney that he felt that the convicts in New South Wales should be subject to the rule of law and not to some arbitrary authority. They did miss out on having a jury of their peers.

The American Revolution of 1776 proclaimed liberal principles, and the French revolution of 1789 liberal and then democratic principles. Democracy made liberalism look dangerous, for the French people had used their new power to chop off the heads of aristocrats and support a reign of terror. While the French revolutionary regimes survived, the British government hounded democrats and refused to contemplate any further liberal reform. But after 1815, when Napoleon was defeated, liberalism strengthened in Britain, with its chief aim the widening of the ranks of those who could vote for parliament.

In 1830, after long years of Tory rule, the Whigs, the reforming party, came to power in Britain. In the first Reform Bill of 1832 they gave middle-class men the vote and rearranged electorates, taking members away from small and decaying towns and allotting them to the new industrial cities. To New South Wales they sent a liberal governor, Richard Bourke. The ministers concerned with this oddball colony took their responsibility very seriously. They were appalled at what their predecessors had done: establishing a society of convicts, which was bound to create a degraded and immoral society. The concern for morality was strengthening alongside support for liberalism. The assumption that a colony of convicts must be degraded overlooked all the ex-convicts who had acquired property and so become defenders of law and order. Still, there was enough crime and drunkenness in New South Wales to give moralists cause for concern.

Viscount Howick, the son of the Whig prime minister, Earl Grey, was the minister responsible for colonial policy. He introduced a scheme to encourage free working people to migrate to New South Wales. In the 1830s there were thus two streams of migration: convicts and free working people. The convicts were still nearly all men; the free workers were men and women in equal number, which would help to redress the sex imbalance, a prime cause of immorality and disorder.

Working people could not afford to pay for the long journey to Australia. Howick got the money for their fares by introducing the sale of the colony’s crown land, rather than giving it away. This was the formula advanced by the colonial reformer Edward Gibbon Wakefield. The selling of land would stop settlement spreading too far, and with the proceeds spent on the emigration of free people the colonies would not have to depend on convicts for their labour force.

The free settlers of New South Wales had not requested such a scheme and were dismayed that the land, which had been available as a free grant from the crown, now had to be paid for. They were even more dismayed when the price of land was ramped up during the 1830s to match the price in South Australia, which had been founded on Wakefield principles without convicts in 1836. The landholders of New South Wales were perfectly happy to go on relying on convicts. But the Whig government had now provided a way for the colony to continue to prosper if transportation were ever to cease.

With the support of the Whig government, Governor Bourke set new principles of equality in the government’s dealing with the churches. Bourke was an Irishman, a Protestant but a liberal Protestant who had seen firsthand the bitterness and conflict caused in Ireland by the British government enforcing support of a Protestant church. Though most of the Irish were Catholic, they had to pay church rates to support Protestant ministers whose services they did not attend. The Whig government was contemplating directing funds to the Catholic Church in Ireland, but it was tricky: there were Protestant dissenters in England who did not want to pay church rates to the established Church of England and would be eager to take changes in Ireland as a precedent. The Whigs had no wish to encourage debate about the funding of the Church of England in England.

New South Wales was easier; the government approved Bourke’s plan to support the Anglican, Catholic and Presby-terian churches on the same basis: the government would pay the salaries of their clergymen and would match the monies they raised for church building. The Catholics had been not altogether excluded from government support in New South Wales but now, at a stroke, they were to gain full equality with the Protestants. It was an amazing measure for Protestant Britain to sanction for its convict colony, and vital for social peace when almost a third of the population was Catholic. The Anglican bishop and other Protestant leaders did not like the government supporting the ‘error’ of Roman Catholicism, but they were pleased to have the promise of more generous support for their own churches. No one denomination could have proposed that others should receive government support as well as itself. This was a measure which only a benevolent despot could propose.

The fight for religious equality was one of the great liberal and radical causes in Britain throughout the nineteenth century. This highly charged issue had been put to rest in New South Wales long before the colony began to govern itself.

Again with the support of the Whig government, Governor Bourke introduced juries of citizens to try criminal cases in the place of juries made up of military and naval officers. In the usual way, jurymen had to own or occupy property of a certain value in order to be eligible to serve. Despite the fierce objections of the free settlers, Bourke allowed ex-convicts who met the property test to serve. The free settlers had some reason for their objection: there was an oddity, to say no more, in inviting former criminals to determine guilt or innocence in criminal trials. In their eyes, that would threaten the integrity of the legal system and damage the reputation of the colony—and their own for living in it. But a larger question was at issue: as the colony acquired the normal legal and political institutions, were the ex-convicts, a large and prosperous class, to be marked for exclusion? Bourke had given his answer.

If ex-convicts could serve on juries, what could be said against allowing them to vote? The battle over juries took place in a larger dispute over the future government of the colony. The British government was contemplating allowing New South Wales the traditional right of a colony to have an elected assembly that could pass local laws.

The demand for an assembly had been pushed by William Wentworth, who had the ambition to confer all the rights of self-government on his native land. He was the son of a convict mother. His father, well connected in the Irish aristocracy, had been three times charged with highway robbery but never convicted. He went into voluntary exile in New South Wales and became very rich. His son was sent home to be educated at Cambridge University. On his return in 1824, he started the first independent newspaper in the colony, The Australian, which agitated for a popular assembly. Wentworth would allow the ex-convicts to vote, and he proposed a property qualification so low that nearly all ex-convict men would qualify. They easily outnumbered the free settlers, so the colony would fall into their hands. This pleased Wentworth no end because he had been snubbed and humiliated by the free settlers.

Governor Darling had tried to curb The Australian and other independent papers but had been frustrated by a liberal chief justice, so that the press was freer in the convict colony than in Britain. Darling could not believe it: he had been sent to make New South Wales a credible place of punishment, and the ex-prisoners had their own newspaper to clamour for their rights and denounce him!

The free settlers were alarmed at Wentworth’s campaign for an assembly and feared that the Whigs might be persuaded by it. They insisted that if there were to be an assembly, property rights alone could not be the qualification for the vote. Ex-convicts would have to show some sign of rehabilitation.

The Whigs came close to setting up an assembly but they worried and delayed. They did not want to impose some contentious test on ex-convicts as qualification for the vote, but nor did they want the colony to fall completely into their hands. Ministers solved the problem another way: they decided to abandon transportation. Once the flow of convicts stopped, the free settlers were less concerned about voting rights for ex-convicts, who would now constitute a declining proportion of the population. Free settlers and the native-born would soon outnumber them.

This is how it was managed. Transportation stopped in 1840, and in 1842 ex-convicts were allowed to vote and stand for a Legislative Council, two-thirds of whose members were elected and one-third nominated by the governor. This body would pass local laws, but the governor and his officials, appointed by the Colonial Office, still constituted the government. Full self-government had not been granted but the impasse over ex-convict rights had been solved.

The free settlers had not proposed the ending of transportation; nor had Wentworth and his ex-convict supporters. Both groups were appalled at the decision because it seemed to threaten the colony’s prosperity and was accompanied by wholesale denunciations of the colony. The Whigs had abolished slavery in the empire in 1834, and now the case against slavery was extended to New South Wales. Society was said to be as debased there as in the West Indian slave colonies. It was not only that the convicts were not properly punished or reformed, but also that the masters had been corrupted by the absolute power they wielded over their ‘slaves’. New South Wales was in fact very different from the slave societies: its ‘slaves’ had rights under the law, and many had former ‘slaves’ as their masters. But the passion now aroused by slavery was enough for the British government to make a decision, which created huge problems for itself: what to do with the convicts? Prisons of the new type would have to be built for them. Meanwhile, transportation was to continue to Van Diemen’s Land, which got many more convicts than it could cope with.

New South Wales was set on the path to becoming a self-governing colony of free people. The convicts already arrived would serve out their terms or gain tickets of leave; ex-convicts had the same legal and political rights as the free settlers; the native-born, chiefly the children of convicts, had always been full British subjects. The need for more labour would be met by the migration of free working people. The process of becoming a colony of free people proceeded smoothly because of the decisions of the British government or its endorsement of what Governor Bourke proposed. In summary, these were the key measures:

- A scheme for the migration of free working people was introduced (which made it possible to stop transportation).

- The Catholic Church (whose members were overwhelmingly ex-convicts or convicts) was granted government funding on the same terms as the Protestant churches.

- Ex-convicts were allowed to serve on juries.

- A local assembly was not granted while ex-convicts and free settlers were in dispute over its composition.

- Transportation was abandoned, which allowed free settlers to accept that ex-convicts could vote and stand for the assembly.

It is a great record of statecraft, but this is not usually highlighted in histories of Australia: who wants to acknowledge that Australia owes so much to the Poms?

Britain was becoming a more liberal society during Australia’s early years but was itself still far from democratic. Amazingly, the British, having laid the foundations for a liberal state in New South Wales, helped to ensure that it was democratic.

The qualifications for voting for the partly elected Legislative Council established in 1842 were set by the British government. It knew that property values were higher in the colony than in England, so the English qualifications would not be appropriate. In England the lowest qualification for the vote was the rental of a house at £10 per year. This gave the middle class the vote in the towns but not the working class. For New South Wales the rate was to be double that: £20 per year. Rents were so high in Sydney that this allowed some skilled workingmen the vote. Overall, though, the rent and property qualifications set for the colony had the same result as in England: only about one man in five had the vote.

With such a narrow electorate the members elected to the Legislative Council were the colony’s elite: large landowners, squatters, merchants and professional men. One of the members elected in 1843 was Dr William Bland, an ex-convict who had been sentenced to transportation for killing his opponent in a duel. William Wentworth, the son of a convict mother, was the leader of the elected members who harassed the governor’s officials (who were nominated members of the council) and demanded that the colony be granted full powers of self-government. Wentworth was putting his rabble-rousing past behind him. The free settlers were now willing to accept him as their political leader, though still not as their social equal.

In 1848 a small group of Sydney democrats—skilled workers and small traders—formed a reform association. They did not dare to demand votes for all men; they asked that the franchise for the Legislative Council be widened. They sent a petition to this effect to the British Colonial Office. The petition would have had no impact, except that it acquired a very effective advocate in London. This was Robert Lowe, a clever lawyer who had made his fortune in the colony and had returned to make his mark in England. He had won one of the seats for Sydney in the 1848 council election with the support of the democrats. He was no democrat himself, but in London he supported a wider franchise for the colony with an argument that could not be used in the colony. He said that under the existing rules, many ex-convicts qualified for the vote but the newly arrived free workingman did not. The usual rules did not apply (was not everything topsy-turvy in the convict colony?): you would get a more respectable electorate by lowering the qualifications.

It happened that a bill dealing with the government of the Australian colonies was passing through parliament as Lowe set up his scare about convict influence in the electorate of New South Wales. The bill provided that the system of a partly elected Legislative Council would be extended to South Australia, Tasmania and the new colony of Victoria, now to be separated from New South Wales. The voting qualifications in these colonies were to be the same as in New South Wales.

By the time this measure reached the House of Lords, Lowe’s argument had prompted a moral panic about convict influence, and their lordships—for the first and last time in their history—made an electoral measure more radical: they halved the household qualification in the towns and gave the vote to small tenant farmers in the country. No one had asked for this in South Australia, Tasmania and Victoria; the group petitioning for it in Sydney was totally marginal. The House of Lords had given the democratic cause in Australia a great boost. Sydney’s elite could not believe it. At the next election, in 1851, Wentworth told the newly enfranchised Sydney electors to their faces that they should not have been given the vote. He only just scraped back in as the third member for the city.

Just as these new qualifications came into operation, the gold rushes began. Property values soared and, as they did, more and more people qualified for the vote. With no change to the law, every householder in Sydney (and in Melbourne) qualified. Every hovel carried a rent of at least £10 per year. Household suffrage was only one step away from manhood suffrage.

In 1852 the British government finally announced that the Australian colonies (except Western Australia) could become self-governing. Each Legislative Council was invited to draw up a constitution for a parliament of two houses. Wentworth was in charge of this process in New South Wales, where the argument over constitution-making was most intense. In this colony, now over sixty years old, a well-established old order was determined to protect itself. Wentworth announced that he planned a ‘British not a Yankee’ constitution. To offset the influence of the workingman householders of Sydney, who already had the vote, he added to the electorate the respectable young men who were lodgers. It was a desperate ploy: he was staving off democracy by giving more people the vote!

Since Sydney and the other towns were the heartland of liberals and democrats, Wentworth allotted most electorates to the country. For the upper house he planned a colonial aristocracy to mimic the House of Lords. When that was laughed out of court, he substituted a nominated house to be chosen by the governor. He protected these two bulwarks against democracy—the imbalance of electorates and the nominated upper house—by providing that they could be altered only by a two-thirds vote in the parliament, a most un-British measure, borrowed from the United States’ constitution.

The Australian constitution was sent to London to be enacted by the British parliament. The officials who checked it noticed that Wentworth had not provided for any general power of amendment. He had been so concerned to ensure that its key provisions could not be readily amended that he had not included any process for the amendment of its other provisions. The officials inserted a general power of amendment for all provisions by a simple majority. This meant that the two-thirds clauses could be repealed by a simple majority.

Wentworth was in London at the time, and protested at this gutting of his work. But he had a formidable antagonist in the secretary of state for colonies, Lord John Russell, who had been a Whig prime minister in the 1840s and the hero of the struggle to pass the Reform Bill in 1832. He wanted the colony to be free to reconsider any part of its constitution, so the new provision which undid Wentworth’s two-thirds device stood.

The first ministry under self-government was conservative, but it promised to repeal the two-thirds clauses. How could this be resisted when the minister in London had so clearly endorsed it? With that barrier gone, a liberal government in 1858 was able to redress the great imbalance in the allocation of electorates. This was more crucial for the establishment of democracy than the adoption of manhood suffrage, which was also carried. That measure added far fewer men to the electoral roll than the changes made by the House of Lords, by property inflation and by Wentworth himself. It disqualified some men, because electors now had to have resided in the electorate for six months to get on the roll and in the colony for three years. The nominated upper house survived because it turned out to be more amenable to popular control than one elected on a narrow property franchise, which was what the other colonies had established. If the upper house of New South Wales was too obstructive, the government could recommend to the governor that new appointments be made.

It is sometimes said that Australian women did not have to struggle as hard to get the vote as their sisters in Britain and America. Australian women got the vote in the new Commonwealth in 1902 and in all the states by 1909. It was nevertheless a struggle from the time of the formation of the first women’s suffrage league in 1884: a long series of meetings, deputations and petitions. Australian women had to stick at it much longer than the men; Australian men got the vote quickly and with almost no struggle at all.