QUESTION 4

WHY DID THE AUSTRALIAN COLONIES FEDERATE?

There were three attempts to federate the colonies in the late nineteenth century. The first, promoted by Victoria in 1883, resulted only in the creation of a weak Federal Council, which not all the colonies joined. The second attempt was a one-man effort begun in 1889 by Henry Parkes, the premier of New South Wales; it produced the 1891 Federal Convention. This body created a constitution for a federal government that was not adopted.

The third attempt began in 1893 at a conference of federalists at Corowa, on the Murray River, who hatched a scheme for the people of the colonies to take charge of the process. They would elect delegates to a new constitutional convention, which would write a constitution to be submitted to the people for their approval. With many hiccups, this scheme was successful. (The key developments are recorded in the chronological table below.) The Commonwealth was proclaimed on 1 January 1901 before a huge crowd in Sydney’s Centennial Park. The Duke of York, heir to the throne, opened the first federal parliament in Melbourne on 9 May 1901.

FEDERATION: A BRIEF CHRONOLOGY

1883

Inter-colonial convention meets in Sydney because of fears of German and French designs in the Pacific. Agrees to form a federal council.

1885–86

Formation of Federal Council, which has miniscule legislative powers and no executive power. NSW and SA decline to join.

1889

Henry Parkes, premier of NSW, calls for a convention to frame a constitution.

1890

Inter-colonial conference agrees to federation in principle and recommends the calling of a convention.

1891

Federal convention elected by the colonial parliaments meets and drafts a constitution.

1891–93

Colonial parliaments debate constitution desultorily; Parkes cannot get support in NSW parliament; proposal lapses.Collapse of banking and financial institutions; general depression.

1893

Formation of Federal Leagues in NSW and Vic. Conference of leagues and the Australian Natives’ Association at Corowa proposes election of new convention by popular vote and submission of agreed constitution to referendum.

1894

George Reid, premier of NSW, supports election of new convention.

1895

Conference of premiers agrees to Corowa procedure.

1897

Elections held for ten delegates to convention in NSW, Vic, SA and Tas; WA parliament appoints its delegates; Qld remains aloof.

1897–98

Convention meets in Adelaide, Sydney and Melbourne, and adopts constitution.

1898

Voters in Vic, SA and Tas agree to constitution at referendums; in NSW ‘yes’ wins narrowly but fails to reach stipulated minimum of 80,000.

1899

Conference of premiers makes alteration in constitution to humour NSW (the capital to be in that colony). Amended constitution agreed to by referendums in NSW, Vic, Qld, SA and Tas.

1900

Edmund Barton, Alfred Deakin, Charles Kingston, James Dickson and Philip Fysh, representing the federating colonies, watch over the passage of the constitution through the Colonial Office and the British parliament. Queen Victoria assents to the Commonwealth of Australia Bill. WA agrees to constitution at referendum.

1901

Commonwealth proclaimed in Sydney at Centennial Park, and Barton and other ministers sworn in. First federal parliament meets in Melbourne.

When I began to study federation, its relationship with nationalism was set out in this way: a national government promoted national feeling but was not caused by it. I have come to hold the opposite view: without national feeling there would have been no federation.

The no-nationalism view held that federation was chiefly a business deal: it created free trade between the colonies and a common market for Australia, and economic interests were its chief promoters. The politicians who actually did the work invoked the nation in their speeches but this was window-dressing. The constitutional conventions were horse-trading bazaars at which the premiers and their cohorts worked to protect the interests of their colonies. You only have to look at photos of the convention delegates to know that there was no nobility in this work: these are middle-class men in suits with beards, a pitiful sub-group of dead white males.

This view seemed more persuasive because federation had not registered in the national consciousness. If we did not remember it, it can’t have been very important to national life. The nation’s origins are well known to lie at Gallipoli and its heroes are not Henry Parkes and Edmund Barton but Ned Kelly, Don Bradman and Phar Lap. When the hundredth anniversary of federation was celebrated in 2001, the Australian people had to be told in TV ads that Barton was their first prime minister.

For the anniversary I wrote a book, The Sentimental Nation, which was designed to counter this view of federation. What follows are the arguments I assembled.

If federation was a business deal, why was big business in Melbourne opposed to it?

This was one of my early discoveries, and I reckon conclusive. Melbourne was the largest city and the financial centre of the six colonies. There was Melbourne money in Riverina sheep stations and Broken Hill mines, in cattle and sugar in Queensland, in mining on the west coast of Tasmania. Business here, if anywhere, should have been in favour of federation.

My discovery happened in this way. I had decided to begin my study of federation by reading through the Daily Telegraph, a Sydney newspaper that was opposed to it. That, I thought, should give me a fresh perspective on an old topic. I was in the State Library of Victoria, reading original copies of the paper in big bound volumes.

In one issue there was a short item on an inter-colonial meeting of the chambers of commerce which seemed to be discussing federation. But there was something odd about the report. I decided I should check the records of the Melbourne chamber. The catalogue told me that the State Library held them, two levels above where I sat. Aren’t research libraries wonderful places! In half an hour I was looking at these records. I soon discovered that the leading businessmen who composed the chamber were in favour of a customs union between the colonies but that they were opposed to federation.

The businessmen considered federation much too difficult: a whole constitution would have to be written; the representation in a federal parliament of the different colonies, large and small, would have to be settled; the powers to be yielded to the central government would have to be decided. It would take forever. Politicians who talked of federation were wasting their time. Let’s do a customs union first, the businessmen argued, which will bring immediate economic benefits, and do the nation later. Their model was the path to unity that Germany had taken. A customs union there was established in 1834, and the nation thirty-seven years later, in 1871. This is the path that Europe has taken in our time: a common market first and a political union still to be realised.

The Melbourne businessmen boasted that they were practical men, concerned just with the bottom line. But all their efforts to foster a customs union failed. The chambers of commerce of the capital cities met at a number of inter-colonial conferences. They could agree that customs barriers between the colonies should be abolished, but what policy should be adopted towards the rest of the world? On this question the two leading colonies had adopted different policies: New South Wales had kept to free trade, the British policy, while Victoria had adopted protection to encourage local manufacturing and farming. The merchants of the Melbourne chamber of commerce had opposed protection, but knew that Victoria would not move to federation unless protection was the policy of the new nation. Merchants in free-trade Sydney knew this well enough, which made them highly suspicious of federation. They were always very wary of conferences on a customs union called by the Melbourne chamber. The conferences met but differences had to be papered over and no joint action ever followed.

But failure did not deter the Melbourne chamber; it kept up the fantasy that business could agree on the terms of the customs union and then present them to the politicians for implementation. Until very late it opposed federation. The secretary of the Melbourne chamber attended the Corowa conference in 1893; he left disappointed because these enthusiasts had resolved to have another try at federation. It was only when federation looked a strong likelihood that Melbourne business came on board; big business in Sydney remained opposed.

The politicians turned out to be the more practical men. Henry Parkes solved the problem of the two leading colonies disagreeing over trade policy. In his call for federation in 1889 he said that these differences should be laid aside. The national parliament should be formed first, and it should be left to settle trade policy. Differences over the tariff were a ‘mere trifle’ compared to the duty of founding a nation.

This was a huge risk for the leader of the free-trade party in New South Wales to take. It was one reason why Parkes’ plan for federation came unstuck. But the next and successful move to federation operated on the Parkes plan. So the appeal to national feeling trumped differences over economic policy. The nation was made first, and then it delivered the customs union. If there had been no national feeling to appeal to, the stalemate between Victoria and New South Wales would have continued. Parkes died in 1895 but his title of ‘father of federation’ is well deserved. The first Commonwealth parliament produced a ‘compromise’ tariff.

If federation was a business deal, why did those working for it call it a ‘noble’, ‘sacred’ and ‘holy’ cause?

These terms appear not only in public speeches but also in the private papers of the leading federalists. They reflected the belief that nation-building was the way to a better future for the world. It was God’s will, or a stage in the evolution of mankind, that all the peoples of the world should have their own state and govern themselves.

Since the wars of the twentieth century, nationalism has looked a dangerous beast; in the nineteenth century it was seen as the way to liberate peoples from tyranny. The great empires of the European landmass—the Russian, Austrian and Turkish—ruled over subject peoples. The Poles, Hungarians, Italians and Romanians, struggling to throw off their imperial overlords, enjoyed the sympathy of liberal, progressive people around the world. Giuseppe Garibaldi, the swashbuckling general of Italian nationalism, had a huge following. In Sydney on his death in 1882, a crowd of 10,000 gathered in the Exhibition Building to mourn him. The Italian float in the federal procession in Sydney on 1 January 1901 carried a bust of Henry Parkes surrounded by Italian soldiers, two of whom were dressed like Garibaldi’s redshirts. The liberal hope was that when all nations were governing themselves, they would come together in a world federation, which would bring peace at last. Lord Tennyson, the British poet lau-reate, sang of ‘the parliament of man, the Federation of the world’.

The federalists in Australia saw their cause as part of this world movement. They were not planning to throw off an oppressor; this was to be a self-governing nation under the British crown. But federation in Australia meant the breaking down of local jealousies and divisions, and the leading of the people into the higher life of nationhood. Instead of being a collection of colonies, Australia would take its place among the other nations of the globe and the march of progress to better things.

This was a cause to which federalists were devoted with a religious fervour. The first two prime ministers of the Commonwealth, Edmund Barton and Alfred Deakin, believed they were doing God’s will in working for federation.

If federation was a business deal, why was there so much poetry?

The scholar who prepared a bibliography of writings on federation decided to spare us the poetry. At one level this was understandable: there was a lot of it, mostly poor and very repetitive. But in excluding it, he took the heart out of the federation movement. The poetry embodied the vision for the new nation: why it should be formed and what sort of nation it would be. That the poetry was repetitious shows how well established the vision was; that people who should never have written poetry composed it shows how moving was this cause. This poetry was not hidden away in literary journals; it appeared in the newspapers, was quoted in federalist speeches, was set to music in support of the ‘yes’ cause at the referendums and was officially encouraged by a prize in 1901.

What became the Australian national anthem, ‘Advance Australia Fair’, composed in 1878, comes from this school of poetry. Its most puzzling line, ‘our land is girt by sea’, was a standard image and in 1878 needed no explanation. The poets considered that Australia, sharing no land borders with other powers and set apart in its own realm, was made for nationhood. Protected by the girdle of the sea, its virtues could flourish unmolested. The words girt, girdling, girdle and girdled were applied as sense and rhythm demanded. Here is a verse from one of the bad federation poems composed by Henry Parkes:

God girdled our majestic isle

With seas far-reaching east and west,

That man might live beneath this smile

In peace and freedom ever blest.

‘Freedom’ was an Australian characteristic, said Parkes. ‘Young and free’, says the national anthem. These, too, were standard themes. The freedom Australians enjoyed was, in the first place, the traditional British freedoms, but in Australia extended to more people: all men could vote. Australia was also superior to Britain because it lacked the barriers of a rigid class system. Opportunity was open to all and there was no inherited privilege. Again, ‘Advance Australia Fair’ gives this theme in shorthand form, ‘wealth for toil’, which carried a double meaning: there was the opportunity to make money and, implicitly, wealth comes only from toil.

The ‘peace’ in Parkes’ verse was not simply freedom from external aggression. The poets celebrated Australian society as unified and hence peaceful: the people were of one stock or blood or race; they spoke one language; there were no ongoing feuds; and, most surprising to us, no blood had been spilt. The frontier battles with the Aborigines were well enough known (the silence or evasion on this matter came later), but Aborigines were assumed to be dying out and so did not register in the national vision. Warfare constantly renewed was the experience Australia was spared.

Australia is young and female in these poems, fresh and virginal. She receives extensive treatment in this guise in one of the better poems, by John Farrell, a Sydney journalist and editor:

We have no records of a by-gone shame,

No red-writ histories of woe to weep:

God set our land in summer seas asleep

Till His fair morning for her waking came.

He hid her where the rage of Old World wars

Might never break upon her virgin rest:

He sent His softest winds to fan her breast,

And canopied her night with low-hung stars.

He wrought her perfect, in a happy clime,

And held her worthiest, and bade her wait

Serene on her lone couch inviolate

The heightened manhood of a later time.

The men worthy to take Australia, the ‘manful pioneers’, only leave Europe when freedom has dawned there:

They found a gracious amplitude of soil,

Unsown with memories, like poison weeds,

Of far-forefathers’ wrongs and vengeful deeds,

Where was no crown, save that of earnest toil.

They reared a sunnier England, where the pain

Of bitter yesterdays might not arise:

They said—‘The past is past, and all its cries,

Of time-long hatred are beyond the main …

‘And, with fair peace’s white, pure flag unfurled,

Our children shall, upon this new-won shore—

Warned by all sorrows that have gone before—

Build up the glory of a grand New World.’

A ‘grand New World’: there is not much of this in the prosaic language of the Australian constitution—except in the name of the new nation, the Commonwealth. This represented an Australian ideal of the state: it existed not to enrich or aggrandise an elite or to embark on conquest, but to serve the commonweal, the common good. The prize-winning poem in the 1901 competition, written by George Essex Evans, linked the name to the standard themes:

Free-born of Nations, Virgin white,

Not won by blood nor ringed with steel,

Thy throne is on a loftier height

Deep-rooted in the Commonweal!

This nationalist poetry is now lost to us—except for the national anthem, which is far from being the best example. The usual account of our literature is that the nationalist school began in the 1890s with the works of A. B. ‘Banjo’ Paterson and Henry Lawson. Their works sold well in the 1890s but no one thought their poems were fit for the celebration of the nation. Nor could anyone then imagine that the nation would come to value most a song about a sheep-stealing swagman and a poem on the exploits of a Snowy Mountains horseman. These writers gave Australians masculine figures to admire who had nothing to do with the public life of the country. The poets who had written of the ideals that should sustain national life rendered Australia as female, a pure young woman.

If, in judging the role of nationalism in federation, we try to imagine the founding fathers singing ‘Waltzing Matilda’, we will get the wrong answer. The founders did know of the pure young woman and all she stood for.

If federation was a business deal, why was it run as a democratic crusade?

The constitution written in 1891 was the work of a convention whose members had been elected by the colonial parliaments. It went back to the parliaments for their consideration. In New South Wales, Parkes could not give it priority because part of his free-trade party was unhappy with it, while the new Labor Party, which held the balance of power, was not interested at all. There was some discussion in the other parliaments, but without New South Wales there was little point in proceeding.

The plan to have the people elect the delegates to a new convention, and for the people rather than the parliaments to pass judgement on the constitution, was designed to lift the cause out of normal politics. There would be a defined process with which the politicians could not interfere. But this open, democratic method was also appealing because in the 1890s there was already a movement to make the colonial constitutions more thoroughly democratic. The federal movement became its standard-bearer, and it did produce an ultra-democratic constitution for the new nation. The anti-democrats who wanted federation had to swallow down their conservative principles, lie back and think of Australia.

The democracy of the 1850s could scarcely speak its name. It was suspect as anti-British and subversive. As we have seen in Question 2, the chief cause behind the widening of the franchise was the inflation of property values, which gave more people the vote without the law being changed. Manhood suffrage was granted but hedged around: you had to be an established resident of the electorate, and the old qualifications for the vote survived so that if you owned property in a number of electorates you had a vote for them all. This was known as plural voting. There was no payment of members. Powerful upper houses in Victoria, Tasmania and South Australia were elected on a narrow property franchise. In New South Wales and Queensland, upper houses were nominated which gave liberal governments some chance of having the governor nominate new members if their measures were being obstructed. Women did not possess the vote and in the 1850s no one proposed that they should.

By 1890 all the colonies had begun paying their members of parliament. This had been pushed chiefly by country people so that they did not have to rely on electing men who lived in the capital city. Its immediate effect was to allow the trade unions to form an effective labour party. Their members could not have entered parliament without payment. Asking unionists to contribute funds to pay for a member was never going to be reliable.

In the twenty years after 1890, progressive liberals with Labor support did chalk up a number of democratic victories. Plural voting was abolished. Residential qualifications for the vote were reduced. Women gained the right to vote. The referendum, the method of direct democracy, was used in South Australia to test opinion on Bible reading in schools and reform of the upper house. Reforming of upper houses did not get very far. They were prepared to widen their electorates, though still requiring a property test for the vote, but not to reduce their powers.

Of these victories, the vote for women was the most spectacular. South Australia adopted this first, in 1894, which made it a world leader, one year behind New Zealand and not far behind the western states of the United States, which were the first to make this change. The feminist history books list the undoubted disadvantages and discrimination women suffered in Australia, but these will not explain why women gained the vote so early in Australia. If oppression alone explained success, feminism would have flourished first in the Middle East.

The key is that most women in Australia had achieved an enhanced position in the home: they were in charge of domestic affairs and the children. The patriarchy outside the home then rankled more; when their half-liberated wives and daughters demanded the vote, it was hard for the menfolk to refuse them. The women’s movement in Australia played on women’s role as homemakers and mothers to get the vote; it did not demand access to all male jobs or to parliament itself. That prospect was what frightened the men, and why, in the United Kingdom and in the eastern United States, the reform was opposed much longer.

The progressive liberals who were in a majority at the constitutional convention of 1897–98 would have liked to have given women the vote for the Commonwealth. But since only South Australia had so far adopted the change, they feared this was pushing the matter too hard. They snuck the women in by a cunning ploy. At the first Commonwealth election the franchise was to be the existing colonial franchises. Thereafter, the Commonwealth could make its own electoral law, but in doing so it could not deprive anyone of the vote who already had it. South Australian women already had the vote; if the Commonwealth was to have a uniform law, then the South Australian practice would have to become the Australian practice. Which is what happened under the first Commonwealth electoral law in 1902.

On other matters, the constitutional convention wrote the new democratic measures into the constitution. There was to be no plural voting. Payment of members was to operate for both houses of parliament (in some colonies members of upper houses were not paid). The voters for the Senate, the upper house, were to be the same as for the lower house. (After 1902 this meant a universal franchise for both houses.) To ultra-democrats, a Senate which had equal representation of the states was undemocratic, which was the chief reason why the Labor Party opposed federation, but an upper house elected on a democratic franchise was unheard of. At this time the United States’ Senate was still elected by the state congresses. Since liberals had been thwarted by upper houses in colonial politics, the constitution provided a system for resolving deadlocks between the houses: an election for both houses, and then, if necessary, a joint sitting to resolve the matter in dispute. (There has been only one joint sitting, in 1974, which was how Gough Whitlam’s Labor government established Medi-bank, the precursor to Medicare, against determined Liberal opposition.) Finally, any changes to the constitution were to be decided by the people at a referendum; this was regarded as an ultra-democratic measure, though it has turned out to be a conservative one. The makers of the constitution assumed an informed electorate and did not foresee the force of the slogan ‘If in doubt, vote no’.

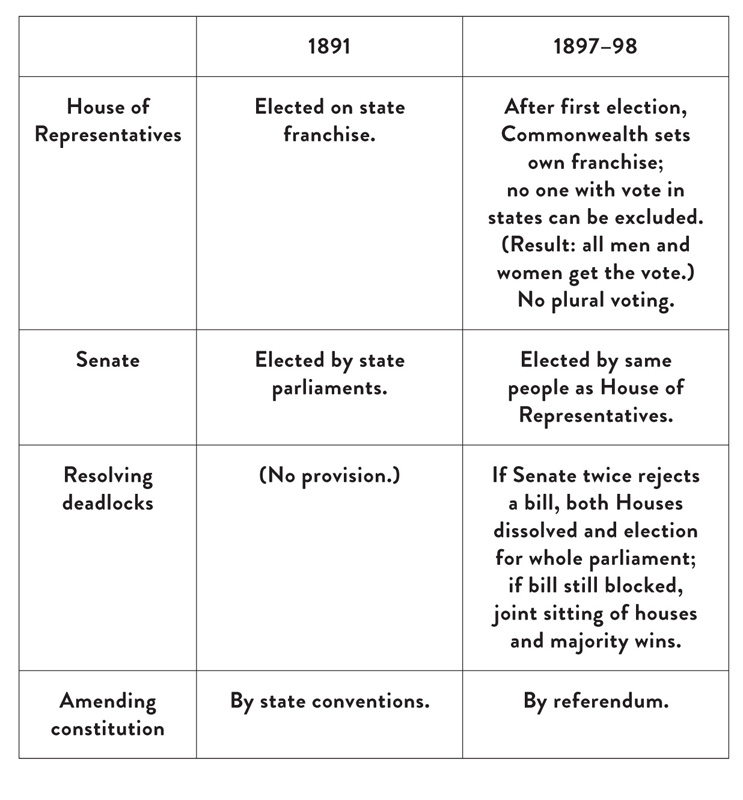

The constitutional convention of 1897–98 was meant to start afresh on writing a constitution. In practice, it worked from the 1891 document drafted by Samuel Griffith, the then premier of Queensland. The chief changes made were those that made the federal parliament more democratic. They are set out in the table on page 108. They indicate the growing strength of the democratic movement and the impossibility of achieving federation on anything other than a democratic basis. Conservative upper houses in the colonies might thwart reform but the new nation was to be democratic from the jump.

Before the Commonwealth could come into existence, the people had to agree via a referendum to accept a document with 128 clauses. There was a ‘no’ campaign with the exaggerations, scares and lies to which we are accustomed. Nevertheless, the ‘yes’ cause prevailed.

The federalists took great pride in their achievement. This federation was not created by military might or the need to unite against an external threat. The Australian people had freely voted to make themselves into a united commonwealth because they saw the benefits that union would bring. What prospects lay before a nation with this pedigree!

DEMOCRATISING THE CONSTITUTION

Comparing the 1891 and 1897–98 drafts

The drafts established two Houses with American names: a House of Representatives, elected by the people, and a Senate, with the same number of senators from each state.

Are economic interests to be left out of this account? Certainly not. Once federation was in prospect, individuals and businesses considered how it would benefit or harm them. The treasurers of the colonial governments were very alert to how federation would affect their budgets, since the central government was now to collect customs duties, which had been one of the colonies’ mainstays. All these interests were active as the constitution was being drawn up and in the campaigns for its adoption. At the referendums there is a clear pattern of the ‘no’ vote rising in places which looked as if they would be harmed by free trade between the states, and of the ‘yes’ vote rising where there was a clear advantage. But these interests did not create the demand for federation. It was the federalist politicians, poets and patriots who were devoted to the cause and worked to achieve it. What was their interest?

They certainly had an interest, though not an economic one. They were interested in the enhanced status that would come to them by belonging to a nation. Whenever Griffith was asked why he supported federation, he answered that he was sick of being a colonial. To be colonial was to be a second-rate, marginal figure; you were defined by your subordinate relationship with a mother country. Griffith, supremely able and highly ambitious, did not want to be taken as inferior. In the constitution he drafted, the word ‘colony’ disappeared. The colonies became states in a new Commonwealth of Australia, to which Griffith gave all the powers of a nation. Defence and external affairs were listed as Commonwealth powers, even though the oversight of these matters rested for the moment with Britain.

In one of his great speeches, in 1889 Henry Parkes expressed the hurt he and others felt from their colonial status:

Instead of a confusion of names and geographical divisions, which so perplexes many people at a distance, we shall be Australians, and a people with 7,000 miles of coast, more than 2,000,000 square miles of land, with 4,000,000 of population, and shall present ourselves to the world as ‘Australia’ … We shall have a higher stature before the world. We shall have a grander name.

For Parkes himself, the other advantage of federation was that he could cap his long career as a colonial premier by being the first prime minister of the Australian nation.

There was one group of people who felt their colonial status most keenly: the first generation born in Australia, the ‘natives’ so called. Their parents were colonials but at least they’d been born in the mother country. The natives were inferior both by birth and by residence. In Victoria from the 1870s, native-born young men ran the Australian Natives’ Association to fight against the slurs they suffered. Their parents and all the people of consequence in Victorian society were gold-rush immigrants of the 1850s. As is common, this generation found many faults in the upcoming generation, which in this case had a simple explanation: they were native-born. The young Australians were criticised for being sports-mad, mentally lazy, disrespectful of authority and great swearers. The natives set out to show that they were sober citizens, fine achievers in many realms, and to contest the notion that if a professor or an archbishop was to be appointed he had to come from the old country. They defended colonial products against the usual prejudice against them, whether they were wine or poetry.

The Natives’ Association ran a medical insurance scheme similar to those run by the lodges, which gave them a sure base of support. At their local meetings, after the insurance business was disposed of, they ran debates, lectures and mock courts—anything that would help with self-improvement and give the lie to their detractors. They did allow alcohol, but not gambling.

In the 1880s they committed themselves to the cause of federation. If a nation could be formed, their deepest purpose would be realised—for who had a greater claim to respect in a nation than the people born in it? They were a Victorian organisation which now had a national outlook. They saw the contradiction and set about to create branches in the other colonies. By 1890 there were branches in all the mainland colonies, though none was as strong as the Victorian, where the clash between the generations was most clear-cut. The Natives’ Association was the one Australian body committed to federation in good times and bad, and ever ready to do the legwork to bring the cause to fruition. Barton kept a list of its branches beside him for reference.

Historians note that the turnout at the federation referendums was lower than at ordinary elections—voting was voluntary—and conclude that there was a lot of apathy on the question. No one knew this better than those who worked to get out the ‘yes’ vote. The historians are in error when they conclude from this that nationalism cannot have been a strong force in federation. National feeling does not have to be universal to be influential. It takes hold first on some groups rather than others. The native-born had a special need for an Australian nation.

When I was a university student, historians commonly looked to economic forces to explain events. It is that view of federation that I have been contesting. Now historians are very interested in race and national identity. This has led to the claim that the chief purpose of federation was to establish the White Australia policy.

At first glance, this claim has a lot going for it. The first substantial measure the new federal parliament passed was the Immigration Restriction Act, which was the legislative basis for the White Australia policy. In supporting the measure, Alfred Deakin, the attorney-general and deputy prime minister, asserted that the chief motive for federation was the desire of the Australian people, acting together through a national government, to protect their racial purity. These were his words:

No motive power operated more universally on this continent or in the beautiful island of Tasmania, and certainly no motive power operated more powerfully in dissolving the technical and arbitrary political divisions which previously separated us than did the desire that we should be one people and remain one people without the admixture of other races.

Deakin was well placed to speak about the federation campaign because he had devoted himself to it throughout the 1890s. He led the campaign in Victoria. The only other man who had done more for the cause was Edmund Barton, who led the campaign in New South Wales. Deakin is an attractive character. He was a profound scholar of the religions of the world; he sought nothing for himself out of public life; he was free of the cruder forms of race prejudice; he was the best of the enlightened progressive liberals who made the Commonwealth. He was also a clever politician, and these eloquent words turn out to be totally misleading.

This is the conclusion reached by Ron Norris, who subjected this claim of Deakin to very close scrutiny in his book The Emergent Commonwealth. Norris looked first at the conferences and conventions which were responsible for the writing of the constitution. At none of these meetings was immigration an important issue. Amid all the arguments advanced for why the colonies should federate, control of immigration simply did not rate. The new Commonwealth was to have power over immigration, but even here there was no sense that this was a matter crying out for national attention. In the 1891 constitution the Commonwealth was to have exclusive power over immigration; in 1897–98 the states and the Commonwealth were both to have power. The founders were envisaging that immigration could go on being a matter controlled by the states; only later would Commonwealth action be necessary.

In the referendum campaigns, extravagant claims and extravagant fears were peddled. Again, the need for national action on immigration did not rate. During the campaign, a Chinese hawker in South Australia was discovered to have leprosy. There was an outcry about this, but no one used the case to show that a national government was needed to take strong action against the Chinese.

The reason for this almost total lack of interest is obvious. The colonies had each passed more or less uniform laws against the Chinese in 1888, which went close to prohibiting Chinese immigration. Some colonies had widened the net in the 1890s and moved against the Indians and Japanese as well, using the device of a dictation test, which was the method used by the Commonwealth in 1901. The problem of Asian immigration had already been solved.

Had it not been solved, it is difficult to imagine that the Chinese would have been allowed to take such a prominent part in the federal celebrations in Melbourne in May 1901. The Chinese merchants of Little Bourke Street put up an arch and used it to get the street decorations extended to their quarter. Two days before the opening of the new federal parliament, 200,000 people watched a Chinese procession pass through the city streets.

So why the swift action against Chinese and other Asian immigration as soon as the parliament assembled?

The ministers who were sworn in on 1 January 1901 had to declare a policy on the vexed issue of the tariff. This was a pressing matter. The inter-colonial trade barriers could come down only when the Commonwealth established what uniform duties were to be collected at the ports. Barton’s government was protectionist, but for the first election it declared for only moderate protection. The opposition leader, George Reid, was campaigning for free trade.

The tariff was divisive and tricky. The new government wanted to go to the people with a popular rallying cry, and in particular with something on which it could compete successfully with the Labor Party, the new third party, which was neutral on the tariff. Workingmen and their unions had always been in the forefront of the demand for a White Australia, and the Labor Party had a White Australia at the top of its platform.

This explains why the Barton government went to the people at the first federal election promising to legislate for a White Australia. The results of the election pushed it to honour that promise. Protectionists and free-traders were close to equal in their parliamentary strength. The balance of power would be held by the Labor Party. Some of their members were protectionists, some free-traders—but all would support a government which was legislating for a White Australia.

The government had to pretend it was responding to some real need on the immigration front. It called for figures on the level of Asian immigration. Ten persons had invaded South Australia since 1899; 133 had swarmed into the Northern Territory, but 151 had left; and 304 Japanese had descended into Queensland since 1898, but 864 had left. Though clearly there was no pressing need, the defining of the nation by the composition of its people made a fitting opening to the Commonwealth’s career.

Much more decisive in ensuring a White Australia was the government’s decision to phase out the use of Pacific Islanders as indentured labourers on the Queensland cane fields. This was announced by Barton in his policy speech and became the chief issue in the federal election in Queensland. The system had been a matter of contention in Queensland for years. It had been marked down for extinction and then reprieved. Labor in Queensland was fiercely opposed to it but had no influence, since a grand coalition of all Labor’s opponents ruled the colony.

The sugar planters had supported federation, since it would open an Australia-wide market for their sugar, but had hoped that any move against their labour force would be delayed. Barton’s immediate move against it outraged them and the Queensland government. The last labourers were to be returned to their islands by 1906. The Commonwealth placed a duty on imported sugar to protect the industry, and an excise was placed on local production, which would be lifted if the planter used white labour. It was a great victory for White Australia when it turned out that white labour on award wages could grow sugar in the tropics.

The origins of the term ‘White Australia’ are obscure. It was certainly coined in the context of an immigration policy directed against Asians. But from our previous discussion of the national poetry, it should be clear why White Australia was such an effective slogan: it caught the pure and virginal themes already present in the national ideal.

The Chinese were seen as a threat to this. Their blood was not British blood. They were inevitably going to be treated as inferiors and, hence, introduce a caste barrier into Australian society and rob it of social harmony. The Chinese would take work at low wages and threaten the high standard of living of the working class. The anti-Chinese agitation popularised the national ideal and gave it, of course, a much stronger racial element. White was not merely a symbol; it was the colour of the citizens’ skins.

Let us return to Deakin. If we think of federation instrumentally, as an arrangement designed to achieve certain objects, then we will say that the desire to exclude the Chinese had little to do with it. But if we think of federation as the realisation of a national ideal, then the exclusion of the Chinese is very definitely part of the story. The agitation against the Chinese gave new power and cogency to the ideal of a pure, pristine, unsullied, united Australia. And that ideal led the federalists onwards. They did want to ‘be one people and remain one people without the admixture of other races’.

The debased view of the origins of federation began with the Labor Party and its supporters. Formed in the early 1890s, the Labor Party took no part in the making of the constitution. There was one working-class representative at the federal convention of 1897–98. In New South Wales and Victoria, Labor opposed the constitution chiefly because of the equal representation given to the states in the Senate. The ‘backward’ states of Western Australia and Tasmania, where there was as yet no Labor Party, were to elect the same number of senators as the two big states. The Commonwealth looked like an anti-democratic machine that would stifle Labor’s progress.

But in the new Commonwealth parliament the Labor Party was amazingly successful, winning seats in both houses in all states, including Tasmania and Western Australia. After the 1910 election it had a majority in both houses, and its highest vote occurred in Tasmania. In 1909 the free-traders and protectionists were forced to amalgamate into the Liberal Party in an effort to stop the Labor advance.

By the time Labor took office in 1910 under Andrew Fisher, it knew that the interpretations given to the constitution by the High Court would not allow it to implement two key parts of its platform: the control of wages and working conditions throughout the country, and the nationalisation of monopolies. In 1911 it put to the people at a constitutional referendum sweeping proposals to increase Commonwealth power and was defeated. It put the same proposals in 1913 and came much closer to success. (For a constitutional amendment to pass, it requires a majority national vote and a positive vote in a majority of states.) When Labor was again strong during the Second World War, it submitted to the people another raft of proposals to increase Commonwealth power and lost again. Labor’s 1947 legislation to nationalise the banks was ruled unconstitutional by the High Court. The constitution quite unambiguously gave the Commonwealth power over banking, but the court ruled that a Commonwealth takeover of the banks was counter to the stipulation of Section 92 that trade and commerce between the states ‘shall be absolutely free’.

Labor’s battle with the constitution led it to write into its platform its opposition to a federal constitution for Australia. It wanted the Senate abolished and a proper national government to be granted full powers. It only dropped these positions in the 1970s. Since then, the High Court has reinterpreted the constitution and given greatly increased powers to the Commonwealth. A federal government can now nationalise monopolies and the banks, but Labor has lost altogether its appetite for such measures.

It is not surprising that the Labor Party could not think well of the constitution-making of the 1890s. Its supporters and sympathisers in the academy, drawing on the Marxist view that the economic interests of classes are the driving force of history, cast the founding fathers of the federation as middle-class men protecting their interests. They were alleged to have created a Commonwealth government of limited powers so that socialism would be impossible to realise. In an influential textbook, Finlay Crisp, who had worked for Ben Chifley’s Labor government, characterised the fathers as ‘men of property’ and read their motivations from that fact. He it was who, in assembling a bibliography of federation writings, decided to omit all the poetry.

Since federation was the only acceptable route to union, an all-powerful central government could not have been created in 1901. Labor’s opposition to the constitution in the 1890s did not concern limited central powers but rather, as we have seen, equal representation of the states in the Senate.

The Labor Party, though sometimes it thinks so, is not the whole nation. Surely others would come to the defence of the constitution-makers? What happened to the honouring of the nation created by an open, peaceful, democratic process? All memory of that passed away.

The forgetting began at the time the federal movement reached its goal. In 1899 the British Empire went to war in South Africa against the Boer republics. The Australian colonies sent soldiers who acquitted themselves well; British commanders were keen to have in their units the mounted horsemen from the Australian bush. There was much more interest in the Boer War and the feats and sacrifices of Australian soldiers than there was in the last stages of the federal movement.

The makers of the federation made a virtue of the absence of military glory in the creation of Australia, but they could not stamp out its allure. The Commonwealth was, after all, baptised by blood. Why the nation could come to think of its birth as occurring at Gallipoli in 1915 rather than in a Sydney park in 1901 was already evident. Though its title might not suggest it, the next chapter will treat the landing at Gallipoli.