Locating Philemon, Colossians, and “Ephesians”

1. Locating Philemon

This chapter’s deliberations begin with a consideration of Paul’s “short, attractive, graceful and friendly” letter to Philemon.1 Philemon is usually included without demurral in the group of authentic Pauline letters, but determining its exigence opens up a useful area of further interpretative possibility within our developing frame. So its data merits careful scrutiny.

The letter describes an intriguing scenario as its immediate exigence. Like 2 Thessalonians 1:4, Philemon 2 lacks a particular geographical association for its reference to an “assembly,” but its addressees are nevertheless quite specific. Although usually referred to as “Philemon,” the letter was addressed to a community. Paul was sending an unhappy slave, Onesimus, or (from the Latin) “Useful,” back to his master, Philemon. We know this because after the prescript, the letter’s address shifts consistently into a first-person masculine mode. However, the letter begins with a communal focus. Philemon was apparently married to Apphia (she is less probably his sister), and they belonged to an assembly that met in the house of a veteran, Archippus.2 So three figures are named initially, along with a house church. Paul was himself in prison at the time of writing — a state he makes much of (1, 9, 13, 23) — and Epaphras is said to be a “fellow prisoner” (ὁ συναιχμάλωτός μου; 23). Paul is also accompanied by a substantial group of “fellow workers” — Mark, Aristarchus, Demas, and Luke, at the least, along with his co-sender, Timothy.

Scholars have pondered the exact situation that underlay Onesimus’s meeting with Paul. I still find Lampe’s (1985a) suggestion persuasive — that Onesimus was not a runaway (fugitivus) but rather a “truant” slave (erro), appealing to a “friend of the master” (amicus domini) for an intervention into a difficult situation. That a runaway slave would contact anyone associated with his master defies all reason (and that Onesimus would just happen to have been arrested and imprisoned in the same cell as Paul, so to speak, seems highly improbable, not to mention that the letter itself is silent concerning an utterly desperate legal situation). But a deliberate if unofficial appeal by an unhappy slave to an authority figure in relation to his master, a slave therefore operating at the time effectively AWOL as an erro, explains the situation in the prison plausibly.3

As we turn from the letter’s immediate implied exigence to consider its location in relation to our frame, it is helpful to note that Paul’s complex strategy on Onesimus’s behalf vis-à-vis Philemon extends beyond the mere dispatch of a helpful letter, to the somewhat intimidating promise of a visit — apparent in his request for the preparation of a guest room (ξενία). And this data, combined with the immediate exigence of a slave operating as an erro, suggests that Paul was imprisoned relatively close by Philemon’s location and hence most probably in the same region or province, and even the same area.

Paul’s pointed request for the preparation of a guest room would seem to suggest a visit rather soon, perhaps within days. And if Onesimus had been away on his unauthorized visit for much more than a few days, he would probably have been declared a runaway or fugitivus, a fearful status that he evidently wished to avoid by contacting Paul. So the letter implies at the least that Paul’s imprisonment was not very far from Philemon’s community, that is, not too many days’ walk in any direction. (This reasoning seems to exclude the Acts-based locations of Caesarea and Rome,4 by way of anticipation.)5 Unfortunately, the letter does not go on to tell us explicitly where either Paul’s prison or the community in question lay. However, some hints in the data are suggestive.

Philemon’s wife, Apphia, possesses a name frequently found in the province of Asia and attested specifically at Colossae.6 And later tradition associated the letter with Colossae, which was located on the border between Lydia and Phrygia, since this was (at the least) the destination of a letter bearing Paul’s name that is strongly associated with his letter to Philemon. So there are hints that the community lay in Asia. And both hints corroborate one another, essentially independently.

Moreover, the letter presupposes an effective founding visit from some member of the Pauline mission. But Paul himself sends no greetings from the local “brothers” at his location, so he does not seem himself to be imprisoned at the site of a successful mission; no local Christian seems to be named besides itinerant members of his circle of coworkers. And this oddly asymmetrical scenario along with the figures specifically named do not obviously resonate with any of the communities that we already know about from the other authentic letters considered thus far, that is, with Paul’s communities in Galatia, Macedonia, and Achaia, in relation to which we have already treated Romans, 1 and 2 Corinthians, Galatians, Philippians, and 1 and 2 Thessalonians. However, if this seems implausible, we know of successful Pauline communities outside of these regions only in Asia, although even in this region, the letter does not resonate with what we know of Paul’s mission in Ephesus (see 1 Cor and, to a lesser extent, 2 Cor), where Prisca and Aquila were present. So we end up, after tracing through these implications — at least in probabilistic terms — with a location prior to the successful Ephesian mission in Asia.

Clearly, this case is far from decisive. Too many figures traveled too far during the Principate for us to place much reliance on the implications of Apphia’s name (and Lydia springs immediately to mind, to nod in the direction of Acts once more); the letter to the Colossians might have been concocted; and the conjunction of evidence here might have been coincidental. Moreover, Archippus’s house church might have been in Lystra or some similar location, with Paul imprisoned nearby (although later data will speak against this). However, I doubt that all these objections can hold good simultaneously, and any counterproposals are utterly unattested. So we will tentatively locate both Philemon and Archippus’s house church in Asia — more specifically, in the regions of Lydia or Phrygia (although the latter might take us into the western reaches of the province of Galatia) — but will refrain for now from building too much on this judgment.7

If Philemon was written in Asia (or western Galatia) prior to the Ephesian mission, then it would predate 1 Corinthians, which we have already determined in chapter 2 was sent from Ephesus to Corinth in the spring of 51 ce. Moreover, in the spring of 51 Paul is in Ephesus looking back on a communication with Corinth (the Previous Letter to Corinth), as well as on other events that had unfolded in relation to that congregation (i.e., Apollos’s first visit to Corinth). He has been evangelizing Ephesus, and apparently a great but challenging opportunity has just arisen for him there (see 1 Cor 16:9: θύρα γάρ μοι ἀνέῳγεν μεγάλη καὶ ἐνεργής, καὶ ἀντικείμενοι πολλοί). So we may extend his ministry and presence in Ephesus back through at least part of the previous winter. And we can chart Paul’s activities through the calendar year beginning in 51 with considerable precision. The letter to the Roman Christians closes this period, leaving him in the spring of 52 contemplating journeys out of the entire area — to Jerusalem, to Rome, and then on to Spain. So it is unlikely that the events eliciting Philemon unfolded after 52. However, we have a considerable chronological window between the Macedonian and Achaian missions undertaken as early as 40-41 ce and the beginning of Paul’s Ephesian ministry late in 50, within which this letter could fall.

We know, moreover, that Paul traveled to Syrian Antioch and to Jerusalem just before the composition of 1 Corinthians, and presumably before the Previous Letter, hence toward the end of this interval (i.e., somewhere from late 49 through mid-50 ce, 13.x years after his first visit to Jerusalem, in late 36 ce). He seems to have visited the Galatians during his return journey, giving them instructions about the collection (1 Cor 16:1). We have not yet determined decisively whether these were “ethnic” or “provincial” Galatians, but the northern route between Syrian Antioch and Ephesus on the journey back from Antioch and Jerusalem could have taken Paul past the Lycus valley and so through Lydia and western Phrygia, and the southern route almost certainly would have.8 Hence, this seems a plausible if tentative location for Philemon and its particular exigence temporally. If Paul was imprisoned during his return journey to the Aegean from Syrian Antioch and Jerusalem, then the data evident in Philemon would be plausibly explained. And this would locate these events in 50 ce, with the incident in Syrian Antioch and Paul’s second visit to Jerusalem (see Gal 2:11-14, 1-10) taking place just before them.9

In sum, the epistolary evidence locates Paul in this general area at this time — in Asia in 50 ce. There seem to be no obvious difficulties with these judgments (at least yet), although some have been made only tentatively, as the evidence allows.

Stylometric data can get little purchase on Philemon, in part because the letter is so short. Meaningful samples usually require around 500 words, and arguably more, and Philemon contains only 335. (As stylometric techniques advance, the relevant word limits are dropping, so this limit may ultimately relax; however, at present it holds.) So we receive neither confirmation nor disconfirmation of the letter’s authenticity in stylistic terms. But should we entertain suspicions about the letter’s authenticity on more traditional grounds?

In fact, few scholars have doubted Philemon’s authenticity, probably largely because of its brevity, specificity, and apparent innocuousness. Raymond Brown (1997, 502) puts the case for authenticity here succinctly: “The [question] is why would someone bother to create Phlm, a note with such a narrow goal, and attribute it to Paul.” The presumption of innocuousness is not especially accurate, however. Baur managed to wring quite a bit of auspicious content from this letter.10 Further, a case could perhaps be made that the letter addresses the issue of slavery for a later ecclesial generation — essentially conservatively, from a modern liberal vantage point. But this situation and address are not notably distinguishable from Paul’s day. Arguably more decisively, Philemon might have been composed to facilitate the acceptance of a more ambitious pseudepigraphon into a Pauline letter collection, namely, Colossians, with which it is closely intertwined. Having said this, however, it seems equally likely that Colossians, if pseudepigraphic, seized the opportunity afforded by the authentic but more innocuous Philemon. Indeed, we can surmise fairly that the presence of Philemon in any Pauline collection was probably bound up with Colossians; it seems unlikely that this short and quite specific letter would have been included without some weightier assistance.11 But its inclusion as a companion letter to Colossians makes perfect sense (and further evidence will be cited shortly in support of this claim). However, this consideration tells us nothing about the letter’s authenticity.

In sum, then, the argument from anachronistic significance is unproved, and the arguments in terms of brevity and specificity still stand. Therefore, the letter’s authenticity will be affirmed in what follows. And with this judgment made, we can turn to consider Colossians — a letter whose authenticity is much more widely contested but that provides rather more data for the question’s assessment. We should recall in doing so, however, that the investigation of Philemon has created an intriguing interpretative option for the location of Colossians, and perhaps thereby for Ephesians as well — namely, a captivity somewhere in Asia in the year preceding the composition of the “major” letters (i.e., 1 Cor, 2 Cor, Gal, and Rom, along with Phil).

2. Locating Colossians

Locating Colossians in relation to our developing biographical frame is a fascinating but complex task; many of its aspects are hotly debated. As usual, however, at this point in our investigation, we will work from the letter itself outward so to speak. So the key initial features of its immediate implied exigence will be explored before we consider the letter’s fit with our developing frame and then the contentions that surround its authenticity in terms of its arguably distinctive style, its use of possible anachronisms, and its ostensible substantive tensions vis-à-vis other letters, especially in terms of eschatology.

2.1 The Immediate Implied Exigence

(1) Paul’s Incarceration

Paul was in prison when the letter was composed. This is hardly problematic, or even surprising, given the immediate locations of Philippians and Philemon, and the claim of 2 Corinthians 11:23, supported by further references to Jewish and Roman punishments in vv. 24 and 25 (. . . ἐν φυλακαῖς περισσοτέρως. . . . ὑπὸ Ἰουδαίων πεντάκις τεσσεράκοντα παρὰ μίαν ἔλαβον . . . τρὶς ἐραβδίσθην; and if Col proves authentic, this takes the ratio of letters written by Paul during an incarceration to 3/9 or 33 percent, a percentage worth pondering — and Eph and 2 Tim could add to it).12 As we will see in more detail momentarily, a significant sequence of events seems to have unfolded while Paul was incarcerated. But this too is scarcely difficult to comprehend. Incarceration in Paul’s day primarily detained people prior to trial. Its duration depended on the speed of the local judicial process, along with its integrity, and this varied a great deal. People could spend years in confinement waiting for trial if the local organization was poor or corrupt. We cannot yet judge the length of Paul’s incarceration during which Colossians was composed; that judgment must await the introduction of the surrounding frame. We can say at this point that, as suggested already by Philemon, Paul does not seem to have been imprisoned in a place that had had a successful local mission, at least yet. He sends no greetings to the letter’s recipients from local brothers, only from named coworkers.

(2) A Proxy Mission in Colossae

The letter states that Paul was not personally known to the Colossians (2:1: Θέλω γὰρ ὑμᾶς εἰδέναι ἡλίκον ἀγῶνα ἔχω ὑπὲρ ὑμῶν καὶ τῶν ἐν Λαοδικείᾳ καὶ ὅσοι οὐχ ἑόρακαν τὸ πρόσωπόν μου ἐν σαρκί). Their existence as a congregation is attributed to one of their own, an apparent slave called Epaphras (1:7). Thus, quite a complex sequence of events must be posited prior to the letter’s composition, which should now be probed for its details and plausibility. I suggest that the data is explicable, largely — and perhaps only — in terms of the following narrative.

As we just noted, Epaphras was apparently a Colossian and a slave (1:7 speaks of Ἐπαφρᾶ τοῦ ἀγαπητοῦ συνδούλου ἡμῶν, and sun- [συν-] compounds are always referentially significant for Paul;13 in 4:12 he is denoted as “one of you” [ὁ ἐξ ὑμῶν] and, again, as “a slave of Christ” [δοῦλος Χριστοῦ]). Hence, Epaphras had to have traveled first to Paul’s location, which was not Colossae, and converted there, presumably having been sent there by his owner.14

Excursus

An alternative scenario is the possibility that Epaphras was converted by the mysterious congregation at Laodicea, or perhaps even in Hierapolis, and then converted his household to that form of Christianity sometime before Paul’s arrival in the area. He could later have made contact with Paul during a trip to Paul’s location, since he was presumably a well-known Christian leader, and have fallen under Paul’s influence at that point. But although it is worth considering, I do not view this reconstruction as likely.

First, Colossians depicts a set of problematic practices at Colossae that Paul views as an intrusion; the Colossians are exhorted to stand firm and not move from what they were originally taught — suggesting that the foundation of the congregation was Pauline. But this original gospel came from Epaphras. If the institution of the church was Pauline, by way of Epaphras, then it follows that Epaphras was almost certainly a Pauline convert.

In support of this principal inference, we can also note, second, that Onesimus traveled to Paul for an intervention, thereby indicating that Paul was perceived to be the key local figure of spiritual authority, and suggesting as well that he was the foundational spiritual figure for the congregation. However, he was introduced to and represented at Colossae by Epaphras. And this is most easily explained if Epaphras was Paul’s convert. At the least, he would have to have been extensively catechized by the apostle. Third, it seems unlikely that Paul would have affirmed Epaphras’s founding role at Colossae so firmly in Colossians if Epaphras had not been considered a trustworthy mediator of Pauline tradition, and this, again, is most easily explained if he was Paul’s convert. And fourth, it would have been implausibly coincidental for Epaphras, a slave, to have founded the congregation from some other source and then to have met Paul and introduced the Pauline gospel decisively at some later point.

Arguments from explanatory parsimony must be used carefully in historical reconstructions of this sort; they can oversimplify complicated situations for which we simply lack the necessary amount of data, overriding the way that the extant data can gesture toward underlying complexities. But in this instance, it seems to be safely applicable. The most economic explanation of the data is the supposition that Epaphras was a convert of Paul’s.

After Epaphras’s conversion, he had to have returned to Colossae and converted some Colossians, who now presumably formed the nucleus of that congregation, if they did not constitute the congregation in its entirety. And Paul must have been imprisoned either during these events or shortly after them, preventing his own travel to Colossae, so that the Colossians had not yet set eyes on him.

But Epaphras is with Paul at the time that Paul writes Colossians to the congregation (4:12-13), so he had returned to Paul’s location at some point. Moreover, although he is characterized positively (4:12-13), he is somewhat surprisingly not returning to Colossae with the letter, which is being sent with Tychicus and Onesimus (4:7-9). So some questions now arise (noting additionally that this narrative will be complicated in one further respect by Philemon). How did Epaphras convert if Paul was incarcerated? Is his conversion in these circumstances plausible? And why did he not return to Colossae with the letter? But these queries do seem to have plausible answers.

Paul might not have been incarcerated when Epaphras converted, but even if he was, Colossians attests to a group of coworkers operating outside Paul’s confinement who could have made contact with Epaphras and converted him as they worked. This circle comprised no less than seven figures, some of them presumably quite experienced missionaries in their own right: Timothy, Aristarchus, Mark (denoted as the relative of Barnabas), Joshua-Justus, Luke, Demas, and Tychicus.15 That this circle might have made contact with Epaphras in some way and then converted him seems entirely plausible. Perhaps they showed inordinate kindness at some point to a slave from out of town, as did Paul to Onesimus, as evidenced by Philemon.

That Epaphras remained with Paul when Colossians was dispatched is also explicable in a number of different ways. Paul’s short letter to Philemon that apparently accompanied Colossians (and here we must anticipate a fragment of information that will be addressed in more detail shortly) suggests that Epaphras had been imprisoned at some time (Phlm 23), and this might help answer this query. If Epaphras had been incarcerated at Colossae for his offensive new piety, then it might have been dangerous for him to return. Having said this, he may simply not have been the most appropriate person to accompany Onesimus and to read out and interpret Paul’s letter. That this slave would have been unable to read seems probable simply on statistical grounds.16 Alternatively, he might have been gifted to the Pauline mission by his master and so now have been operating with the Pauline group and no longer at Colossae, as Paul seems to have hoped in the case of Onesimus (here again anticipating information from the frame).17 So once again, a plausible explanation of the data seems possible, although, unfortunately, it is hard to know which scenario actually obtained.

With the role of Epaphras clarified — or at least plausibly explained in various possible ways — we should turn to consider another odd suggestion within the letter concerning its implicit prior events.

(3) The Congregations at Laodicea and Hierapolis

The letter to the Colossians indicates the existence of congregations at Laodicea and Hierapolis (2:1; 4:13, 15, 16), which seems at first glance even stranger than the prior foundation of the community at Colossae by proxy. But we do not need to suppose that members of Paul’s circle, assisted by Epaphras (or vice versa), had founded these congregations in the time available in addition to the congregation in Colossae, something that is perhaps implausible, although it probably should not be excluded outright. Nothing in the data necessitates this. That they had had time to visit these communities in the interim, learning Nympha’s name, for example (Col 4:15), is plausible.

If we lean on the Asian (provincial) provenance of Colossians at this point (again anticipating a contribution from the frame by way of Philemon), this phenomenon is even more understandable. The existence of pockets of converts in the Lycus valley ca. 50 ce independently of the Pauline mission is by no means impossible. As we have already noted, the area was on the main southern east-west route through Asia Minor and was studded with large Jewish communities (see esp. Trebilco 1991). Christian growth was intimately related to Jewish networks, at least in its early years (see esp. Stark 1996). Hence, that converts had “leaked” into this area independently of Pauline missionary work is plausible (and later data will speak to this question as well).

Paul’s work had hitherto been much farther to the west, in Europe, and to the east, in Galatia and beyond (i.e., Cilicia, Syria, the Decapolis, and Arabia). Only now do we have epistolary evidence of him circling back to the huge area lying between these regions, namely, Asia, where these mysterious converts were encountered — and apparently much had happened in the intervening decade. Paul’s mission had no monopoly on conversions, much as he might have wanted one. So rather than being problematic, it is simply somewhat fascinating to see congregations coming suddenly into view from another missionary trajectory, perhaps in combination with some migration (i.e., the origins of the Laodicean congregation need not have been in Laodicea; Christians may have converted elsewhere, possibly in contact with Jewish Christians, and then migrated to this prosperous town).

These three broad prior narratives — Paul’s incarceration, the existence of a successful proxy mission at Colossae, courtesy of the convert Epaphras, and the further existence of two congregations of unknown etiology at Laodicea and Hierapolis — distantly inform the composition of the letter to the Colossians. But the letter suggests that particular events flowing from these broader situations actually elicited its composition. More specifically, one principal event brought two distinguishable issues to Paul’s attention and thereby seems to have catalyzed the composition of Colossians and Philemon; and another immediate sequence of events, which is very important for the subsequent interpretation of Colossians in relation to Ephesians, becomes apparent at this moment as well. We will note these features of the situation briefly here; they will be described in more detail in later subsections, since they spill over into considerations of framing, dependence, and possible pseudonymity (see §§2.2, 2.3, and 2.4).

(i) The arrival of Onesimus with news of Colossae. The key event in immediate terms that catalyzed the composition and dispatch of Colossians was the arrival of Onesimus at Paul’s place of imprisonment. Paul’s letter to the Colossians implies that Onesimus brought information that made Paul concerned about the presence of a new bundle of conceptual, linguistic, and cultural practices at Colossae. In large measure, Colossians presents itself as having been written to correct these.18

The perceived problematic teaching is often dubbed “the Colossian heresy,” but this is slanted and unhelpful; it subliminally suggests the anachronistic origin of this material after the time of Paul when the later church was identifying orthodoxy and heresy more precisely (and even the manner in which this complex development took place is much debated).19 It may be that this teaching does ultimately have to be identified with later heresies, thereby identifying Colossians as pseudonymous. But this question should not be prejudged. In the first instance, then, as usual, we will give the benefit of the doubt to the letter in question and dub this material “the Colossian teaching,” noting that it seems to have included various practices, theological and otherwise.20 We will press this teaching for anachronistic details in our final subsection here (§2.4). For now, we need to ask whether this sort of epistolary response by Paul is plausible, and of course it is.

The problematic material at Colossae might well have been introduced by a third party. The congregation was founded by Paul’s convert, Epaphras. Much of the letter’s rhetoric then resists a perceived deviation from what was initially taught, exhorting its recipients to remain firm and steadfast, and to grow from their initial location (see esp. 2:6-7),21 a location tied to Epaphras and in turn to Paul. Moreover, it occasionally gestures toward the presentation of an alternative point of view by someone else (see esp. 2:4, 8, 16, 18).22 So it seems fair in the first instance to attribute the problematic Colossian teaching tentatively to an interloper, although not much turns on this judgment at this point.23 And Paul wrote almost all of his other letters to congregations that had been affected by third parties in ways that he thought were unhelpful — the perennially important insight of F. C. Baur (2003 [1845]). Of the eight letters we have analyzed thus far, only two do not evidence this function, at least to some degree — 1 Thessalonians and Philemon.24 And this suggests the fundamental plausibility that an incarcerated Paul would write a letter, here Colossians, to correct perceived problems at Colossae introduced by someone else. Moreover, a degree of urgency is now quite possibly imparted to the letter’s exigence; the rot at Colossae would need to be stopped, and any further spread prevented.

But Onesimus’s importance for the composition of Colossians was not exhausted by his report concerning this intrusive teaching. He had not traveled to Paul’s location to inform him of subtle congregational aberrations; this information seems to have arisen inadvertently. He had traveled on a more desperate and less subtle errand — to seek intervention into a difficult domestic situation, the exigence that elicited Philemon, although this aspect of the situation is best addressed momentarily, in §2.2, when framing considerations are explored.

These, then, are the two key issues brought to light by Onesimus’s arrival that need to be appreciated, both of which elicited letters in a partly overlapping response. His information about the new teaching in the Colossian congregation elicited an epistolary correction — Colossians — which was possibly relatively urgent. And his own difficult situation elicited a short epistolary response — Philemon — possibly accompanied by a subtle response in various parts of Colossians, which we will explore shortly. That Onesimus even traveled to Paul, however, bringing him information about the Colossian congregation, was caused ultimately by the proxy mission, which the letter attributes to Epaphras. And Paul’s response in the form of letters, over against a visit, was necessitated by his incarceration.

(ii) The writing and dispatch of a letter to the Laodiceans. One final feature of this complex implicit situation needs to be appreciated before we move on. Paul instructs the Colossians at the end of their letter, in 4:16, to have the letter read to the Laodiceans, and vice versa, to read the Laodiceans’ letter themselves. This is a nice confirmation (if it proves authentic) of our earlier supposition that Paul’s letters were circulating freely to congregations beyond their named recipients.25 Moreover, although the point is not overt, it probably entailed the making of copies; it seems unlikely that the congregations would have exchanged their original copies of these precious letters. When Paul tells the Colossians “to make it so that it [i.e., this letter] should be read in Laodicea,” ancient letter readers would have thought first of making and sending a copy — and this might suggest that the sequence of towns away from Paul’s place of imprisonment began with Colossae. The first town reached would have been responsible for making any initial copies of multiple letters, here apparently Colossae. The Colossians would have had to copy the letter to the Laodiceans for themselves before the original went on to Laodicea, and equally importantly, to make a copy of Colossians to send on as well. Paul’s short letter to Philemon was understandably not involved in this duplication. (We will return to this question momentarily.) But because of this rationale, we cannot determine from Paul’s instruction the order of the letters’ composition — an important realization (to which we will also return shortly). Nevertheless, this telltale instruction is of course interesting not merely because of the light it sheds on the exchange of ancient letters. It reveals that another letter existed in immediate proximity to Colossians and Philemon, written to the Laodiceans, who also had not met Paul personally.

We should note immediately that it is not at all unlikely for Paul to have written a cluster of three letters in prison at this time. Unfortunately, it is well attested through human history that incarceration is a fertile space for reflection and literary work, especially by (literate) activists. This space affords them time like no other to reflect, think, and compose. The result can then be work of a truly definitive nature, provided that the material can be written down in some way and retrieved from the prison. Two famous and more recent examples of such activity are Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s letters and reflections written from prison during the last stages of World War II (collected and published posthumously in Bonhoeffer 2010 [1953]) and the “Letter from Birmingham Jail” written by Martin Luther King Jr. in 1963 (see 2004 [1963], 1896-1908). But these well-known instances barely ruffle the surface of the sea that is prison literature. (A particularly interesting example in this relation is the seventeenth-century Anabaptist anthology The Bloody Theater, collated originally by Van Braght 1951 [1660].)

The existence of this letter to the Laodiceans immediately alongside Colossians opens up a critical interpretative possibility within our developing frame that we will have to assess carefully in due course, namely, whether the letter we now know as Ephesians should occupy this locus — whether Ephesians equals Laodiceans. If Ephesians does not fit this space or, alternatively, if it fits another space better, then we need simply to note that Paul’s letter to the Laodiceans is no longer extant, like the Previous Letter to Corinth and most of the Previous Letter to Philippi, and any inquiries here in relation to Colossians will largely have to stop. But if Ephesians does equal Laodiceans, so to speak, then the implications are potentially significant. Clearly, the whole question will be best considered after Ephesians is introduced into our discussion, in this chapter’s third major section. For now it suffices to note that another letter was written by Paul at the same time as the composition of Colossians and Philemon, a letter addressed to the congregation in Laodicea (2:1; 4:13, 15, 16). And this observation rounds out all the key matters of immediate implied exigence.

The situation surrounding the composition and dispatch of Colossians was clearly layered and complex. But at this stage in our discussion, it is more interesting than problematic. Nothing in the letter’s immediate implied exigence indicates that it was pseudonymous, so we can now turn to consider its location within our developing frame.

2.2 Framing Considerations

We have already used fragments of information derived from the frame when discussing the immediate implied exigence of Colossians, but this letter is so embedded in its local situation, with its complex interwoven narratives and communications, that isolating it entirely is both impossible and undesirable. However, we have yet to engage in detail with Colossians in relation to our broader frame, a task that should begin by exploring the subtle relationship between Colossians and Philemon.

It is perhaps seldom appreciated just how tightly Paul’s letters to Colossae and to Philemon fit together. Most obviously, the co-senders, principal actors, and final greeters are all almost identical. (Possible aberrations in the greetings will be addressed momentarily.) Paul and Timothy are writing to figures identified — if the two letters accompany one another — as Colossian. Archippus is the head of the house congregation of which Philemon, Apphia, and now Onesimus are evidently members (Philemon 1–2); and he is addressed directly in Colossians 4:17. Onesimus is identified as a Colossian in Colossians (4:9), and is clearly returning home in Philemon (i.e., at least in some sense). Aristarchus, Mark, Epaphras, Demas, and Luke, at the least, send their greetings in both letters. So the basic elements in the letters match almost perfectly, although this would perhaps not be surprising in a careful pseudepigraphic work. However, even more impressive is the subtle substantive interlacing of the two letters.

Paul’s letter to the Colossian congregation as a whole, as we have just seen, is principally concerned with the new Colossian teaching, news of this having apparently been brought to Paul somewhat fortuitously by Onesimus. The shorter letter to Philemon (as well as to Apphia, Archippus, and his house congregation) addresses Onesimus’s difficult domestic situation directly. But it is intriguing to note how the longer congregational letter, Colossians, in a secondary rhetorical dynamic, also participates subtly within a broader strategy focused on ameliorating Onesimus’s plight.

The letter to Philemon addresses the situation directly with a number of specific pleas. It also promises a visit from Paul himself as soon as circumstances permit. But Colossians reveals that Tychicus might have been part of Paul’s plan to manage the conflict. There is no suggestion that he was a Colossian convert, although he seems to have been a slave (see σύνδουλος in 4:7). But he was an outsider, a member of Paul’s circle, and presumably literate, and so possibly he would have been able to exert more leverage on various Colossians than one of their own slaves, Epaphras.

More overtly, the letter to Colossians instructs the congregation to “tell” Archippus to complete his “ministry” (4:17: καὶ εἴπατε Ἀρχίππῳ· βλέπε τὴν διακονίαν ἣν παρέλαβες ἐν κυρίῳ, ἵνα αὐτὴν πληροῖς). And this direct address in Colossians 4:17, along with the inclusion of Archippus in the address of Philemon, has often puzzled interpreters. But this is perfectly comprehensible as part of Paul’s broader strategy designed to manage the conflict between Onesimus and his owner, Philemon. Philemon is evidently a member of Archippus’s house congregation; Archippus is his minister. So Colossians and Philemon draw Archippus subtly but firmly into the domestic conflict, placing local congregational and rhetorical pressure on him to “complete his ministry.” Indeed, by 4:17 the letter has carefully constructed an account of ministry in relation to Paul, Epaphras, and (to a lesser extent) Tychicus (see 1:7, 23-25, 28-2:7; 4:7-8, 12-13). Ministers are to be trustworthy, and to exhort, to pray, and even to struggle to present everyone perfect and complete in Christ. So Archippus is drawn remorselessly into a proper ordering of the relationship within his house church between the owner, Philemon, and his slave, Onesimus, and is instructed in how to behave as he carries this out, while the community is simultaneously reminded of his authority and called upon to ensure his faithful action.

Like many NT texts, Colossians provides instructions about community order in terms of the Haustafeln. But it is interesting to note that these instructions are disproportionately concerned in Colossians with the relationship between owners and slaves. The four key family relationships — wives, husbands, children, and parents — receive one brief verse of instruction each. But slaves and masters are instructed for five rather longer verses, which is almost twice as much exhortation as the rest of the Haustafeln combined. By way of comparison, Ephesians provides twenty-one verses of admittedly distinctively expanded exhortation, but only five are directed to owners and slaves. The disproportion is striking, but it is fully comprehensible if Colossians has one eye on the conflict between Philemon and Onesimus. The baptismal instructions in Colossians are then equally suggestive.

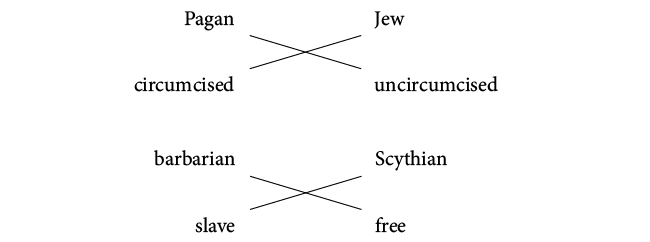

Colossians 3:9-11 famously echoes 1 Corinthians 12:13 and Galatians 3:26-28 (although, according to our developing frame, these last texts would not have been composed when Colossians was written). However, the binary couplets transcended in this instance are “pagan [lit. Greek] and Jew, circumcised and uncircumcised, barbarian, Scythian, slave, free.”26 And these have consistently puzzled interpreters. Unlike Galatians 3:28 (but like 1 Cor 12:13), Colossians 3:11 contains no mention of the transcendence of “male and female.” And Colossians adds an otherwise unattested couplet, “barbarian, Scythian,” which is decidedly odd. Its members are opaque, especially the category “Scythian,” which refers literally to a feared nomadic people inhabiting the great Eurasian steppe (although they were, strictly speaking, long extinct by this period, their place taken by other nomadic peoples). Moreover, this does not seem to be arranged in any obvious contrasting opposition as the other couplets are (i.e., Jew versus pagan, slave versus free). Barbarians and Scythians seem to come from the same category (i.e., barbarians). However, these problems are eliminated once it is grasped that the entire series of couplets in Colossians 3:11 has been arranged chiastically, and furthermore, that it thereby speaks directly to the conflict at Colossae between Philemon and Onesimus.

The category “Scythian” was not just a traditional Greco-Roman designation for “the nomadic barbarian other” from the steppes. It was frequently applied to those who had been enslaved from the region, presumably by means of raids along the shores of the Black Sea. Hence, “Scythian” was an attested slave name. (This was probably not just typical slave nomenclature; members of this savage race would have fetched a higher price.) And the largest local emporium for the sale of these slaves was Ephesus. It seems significant, then, that the category “Scythian” is coordinated chiastically by Colossians 3:11 with the category “slave,” and the category “barbarian” with the category “owner” (technically, the word used here is “free,” which would encompass more than just owners; contextually, the use of the word “free” would be especially pointed for owners).

These coordinations map directly onto and further illuminate the situation at Colossae that is principally disclosed by Philemon. Onesimus may have been, it seems, one of the unfortunate “white Russians” enslaved by a Black Sea raid, and was very likely sold in Ephesus or one of the other great port emporiums on the western Aegean coast (although his place of acquisition does not matter overmuch). That he is now associated with Colossae is therefore plausible. His master, Philemon, is identified here as a barbarian, and his wife’s (or sister’s) name attests plausibly to this identification as well; he is probably a Phrygian or Lydian, something that is again not surprising for a citizen of Colossae. The carefully crafted baptismal chiasm in Colossians 3:11 thereby suggests that the difficulties between Philemon and Onesimus have an ethnic as well as a class component, a doubly difficult situation to navigate. So Colossians maps in detail here the unfolding situation addressed directly by Philemon. And it is worth noting that without this illumination, these textual details in Colossians remain opaque; they are literally uninterpretable.

Enough has probably been said by this point to suggest that the problem of slavery and its pastoral management identified by Philemon are woven into the warp and woof of Colossians (although even more material could arguably be introduced in support of this claim). The involvement of the local deacon Archippus in both Philemon and Colossians, the unusual emphasis in the Haustafeln on the relationship between owners and slaves, and the inordinate applicability of the unique baptismal material in 3:11 lace these two letters and their situations tightly together. We might want Paul’s advice concerning slavery to be rather more radical than it is, but that is not our current concern; we need only to recognize here that the issue is writ large through the text of Colossians, if in a somewhat regrettable sense.27 Yet unlike the overlaps between the prescripts and postscripts, this interlacement is not especially noticeable; it is easy even for modern commentators to miss these clues. And this serves to corroborate a judgment of authenticity as against pseudepigraphy concerning Colossians, at least at this stage in our discussion. As Paley put it some time ago: “This result is the effect either of truth which produces consistency without the writer’s thought or care, or of a contexture of forgeries confirming and falling in with one another by a species of fortuity of which I know no example” (1790, 111).

With some confidence, then, we can turn to consider the immediate implications of the interlacement of Colossians and Philemon for the rest of the frame. The first implication worth noting is the reinforcement of the letters’ Asian provenance.

We learned from Philemon primarily that Paul was most probably imprisoned quite close by Onesimus’s place of ownership. Onesimus had reached him as an erro, and part of Paul’s response was to request the preparation of a guest room. There were hints that these locations were in Asia, but they were very tentative (i.e., Apphia’s name; later tradition’s association of Phlm with an Asian provenance by means of Col; and the general suitability of this location against what we know of Paul’s situations elsewhere). We learn from Philemon, in short, something about the distance that Paul was from his recipients but not definitively where those recipients were located.

Paul’s letter to the Colossians, however, clearly identifies its recipients as Colossian. And the tight connections between these two letters now allow these sets of data to be confidently combined, suggesting that Paul was somewhere in the Lycus valley when he wrote these letters, or nearby. That is, we now know with some confidence that he was not far from his recipients, and his recipients were Colossian. And this corroborates our earlier chronological estimates as well, made somewhat tentatively in relation to the hinted Asian provenance of Philemon. So we can now confirm more confidently that the imprisonment in question was during 50 ce, apparently occurring while Paul was returning from Syrian Antioch and Jerusalem by way of Galatia. But Colossians now adds further important details to this developing picture.

Paul was not imprisoned in Laodicea or Hierapolis or Colossae itself. Moreover, he seems to have been positioned east of Colossae and these other communities, looking west toward them, so somewhere most probably on the important route between Laodicea and Pisidian Antioch by way of Apamea, the important town located on the eastern frontier of the Roman province of Asia.

Modern people tend to think about locations and distances and to plan any travel accordingly “from above” (i.e., as if they were in a helicopter or plane), largely because of the cartographical revolution that took place from the Renaissance onward that depicts our environments in this fashion. And most modern scholars tend to think about ancient travel in the same terms — topographically, and in fairly accurate, two-dimensional and three-dimensional terms, a purview doubtless assisted by the provision of accurate maps in modern printed editions of the Bible. But this is of course anachronistic. Modern topography in these terms, based on spatially accurate cartography, became possible only after the discovery in the fifteenth century of accurate surveying techniques based on telescopes, magnetic compasses, and sextants, along with the invention and standardization of various mapping codes that modern readers take for granted — the introduction of the Mercator projection in 1569, for example. The mental landscape of ancients was very different.

It is becoming increasingly clear that Romans and other ancient peoples thought about distance and travel primarily in terms of sequences or itineraries, like beads on a string, that could lead them reliably from their current location to a destination (ironically, rather in the way that programs like Google Maps or MapQuest produce sequenced travel itineraries today, thereby returning us to ancient mental maps; see esp. Scheidel, Meeks, and Weiland 2012; Scheidel 2013). This purview is represented well by the Peutinger Table (i.e., the Tabula Peutingeriana; see esp. Talbert 2010), whose archetype probably dates from the fifth century ce. It is highly significant, then, that several times the postscript of Colossians suggests that Paul is thinking in terms of an underlying itinerary or sequence that runs from east to west.

In 4:13 Paul thinks of Colossae, then Laodicea, then Hierapolis (μαρτυρῶ γὰρ αὐτῷ ὅτι ἔχει πολὺν πόνον ὑπὲρ ὑμῶν καὶ τῶν ἐν Λαοδικείᾳ καὶ τῶν ἐν Ἱεραπόλει). In 4:15 he thinks of Laodicea, then of Nympha’s house congregation, which seems to have been located in Hierapolis (Ἀσπάσασθε τοὺς ἐν Λαοδικείᾳ ἀδελφοὺς καὶ Νύμφαν καὶ τὴν κατ’ οἶκον αὐτῆς ἐκκλησίαν). And in 4:16 he thinks first of Colossae and then of Laodicea, before reversing the sequence (καὶ ὅταν ἀναγνωσθῇ παρ’ ὑμῖν ἡ ἐπιστολή, ποιήσατε ἵνα καὶ ἐν τῇ Λαοδικέων ἐκκλησίᾳ ἀναγνωσθῇ, καὶ τὴν ἐκ Λαοδικείας ἵνα καὶ ὑμεῖς ἀναγνῶτε). And the three primary sequences all run consistently in the same direction — east to west.

If Paul was thinking in terms of itinerary or sequence, then, as was most common in the ancient world, we may infer with considerable confidence that the envisaged itinerary ran west from Paul’s current location to Colossae, then to Laodicea, and finally to Hierapolis, the community westernmost from him. This is not necessarily to suggest that these communities were on a straight line or direct route with respect to one another. But the most practical order in which to visit them from Paul’s place of imprisonment would have been in this sequence, and this strongly suggests locating Paul’s imprisonment to the east.

We should now combine this inference with the implications from Philemon concerning the relatively short distances involved and the additional suggestion that Paul is not apparently writing from a place where a successful congregation had been established. It seems likely in the light of this evidence that Paul was imprisoned somewhere between Colossae and — let us say for the moment — Pisidian Antioch, the gateway to south Galatia, where a successful congregation had been founded (although little changes here if we switch the city of origin to a gateway to north Galatia such as Dorylaion/Dorylaeum).28

Pisidian Antioch was around 6.4 days’ journey on foot from Laodicea (utilizing ORBIS here). And Colossae was less than half a day’s walk from Laodicea back toward the east (ca. 16 km; note that Colossae is too unimportant to be mapped by ORBIS, at least yet). So we may infer fairly that Paul was imprisoned somewhere to the east of Colossae and no more than six days away, and there is one particularly appealing candidate for this imprisonment: Apamea.

The strategic city of Apamea was one of the gateways to Asia from the east and was located only 2.9 days’ walk from Laodicea (105 km), and even closer to Colossae (2.4 days’ walk or ca. 89 km). There are no records of a successful Pauline congregation being established there, although isolated conversions were presumably possible. And it was certainly a sufficiently large administrative center to have had officials willing and able to detain someone like Paul. It seems fair to suppose, then, that Paul was imprisoned in Apamea when he wrote Colossians and Philemon; either this, or he was being held in some similar location and situation between Colossae and Pisidian Antioch (or, alternatively, Pessinus), although the other candidates do not fit the parameters in the data quite as well as Apamea. Dorylaion is a candidate, but is almost ten days’ journey distant, which seems a little far. However, nothing rests on a precise location at this point, so we will with due caution suggest Apamea as the best current candidate for the locus where both Philemon and Colossians were composed, remaining open to other possibilities. We can now turn to consider potential questions within the data that might challenge our initial judgment here of authenticity concerning Colossians:

(i) Is there time during Paul’s imprisonment for all the implied sequences of events to have taken place?

(ii) Is there an unacceptable disjunction between the addressees in Colossians and those in Philemon?

(iii) Is there contradictory information in the two letters’ lists of greetings?

(iv) Does additional data concerning other figures in the Pauline mission contradict the scenario currently being advocated — that is, an early date for these letters’ composition from somewhere in Asia prior to any missionary work in Ephesus taking place?

(v) And why are these letters silent about the collection for the poor in Jerusalem, which was unfolding at this time?

These could pose difficult challenges, but I suggest that there are plausible rejoinders.

(i) The duration of the incarceration during which Colossians was written is limited, at its maximum possible extent, only by the events that took place at either end. Is there time between these events for a relatively lengthy imprisonment during which the events presupposed by Colossians could have occurred? Or is there too much time compression evident here, suggesting that Colossians is a forgery?

As we have already noted briefly, this period is bound on its early end by Paul’s departure from Galatia after traveling back from meetings in Syrian Antioch and Jerusalem, and those took place as early in the relevant chronological interval as late 49 ce (i.e., 13.x years after Paul’s first visit to Jerusalem, which occurred in late 36 ce). The late end of the period is bound by Paul’s arrival in Ephesus in time for the events presupposed by 1 Corinthians to have taken place, and these could have unfolded as late as the final months of 50 ce. This establishes the widest possible interval for the period in question — roughly December 49 through November 50 ce. We must reckon with the appropriate travel times within this interval, however.

A sea journey from Jerusalem to Antioch would have taken about a fortnight, and a journey from Syrian Antioch to Apamea by way of Galatia on foot about 21 days, or three weeks, so approximately five weeks total.29 So if Paul left Jerusalem in January and arrived in Ephesus the following fall, around September, then he could theoretically have been incarcerated in the Lycus valley from March through August, a six-month sojourn (and this estimate is not pressing the limits of the situation). He need not have been in prison this long, but there is clearly enough time for the events implied in Colossians to have unfolded around him during an incarceration of this potential duration. Time compression is not a problem.

(ii) There is possibly a problem, however, buried in the prescripts of Colossians and Philemon. Paul’s letter to Philemon is addressed to Philemon, to his wife Apphia, and to Archippus “and the assembly in your [masc. sg.] house” (Phlm 1–2). Paul’s letter to the Colossians addresses the “holy and trustworthy brothers who are in Colossae” (Col 1:2). Later in the letter, as we have already seen, it also exhorts the letter’s recipients to (paraphrasing) “tell Archippus to get on with his appointed spiritual task” (4:17). And this does not make a lot of sense if the addressees in the prescript of Philemon were identical with the congregation at Colossae.

Yet while this skepticism is warranted in general terms, it must give way in the face of specific data, which seems to suggest here that the entire Colossian congregation was larger than the house church addressed in Philemon. Arguably, fragments of epistolary data confirm this. Paul never addresses the recipients of Colossians as an ἐκκλησία, or assembly. Only assemblies in Laodicea and Hierapolis (the latter presumably being a single house gathering) are named as such. (The references in Col 1:18 and 24 are generalized and distinctive.) The prescript to Philemon also names a single house gathering. This suggests that the Christians in Colossae were gathering in more than one house congregation. And when this data is combined with the probable presence of a rival teacher at Colossae, it seems possible to imagine that conversions at Colossae numbered significantly more than the single household gathering named in Philemon 1b-2. This figure or group may have had some success, too, analogous to the situation at Corinth. But a further problem lurking in the two lists of greetings is more difficult to deal with.

(iii) Epaphras is characterized as a “fellow prisoner” in Philemon 23 (ὁ συναιχμάλωτός μου) but not in Colossians, while Aristarchus is characterized as a “fellow prisoner” in Colossians 4:10 but not in Philemon 24. Consequently, it seems at first glance as if Aristarchus was in prison with Paul when Colossians was written, but Epaphras was in prison with Paul when Philemon was written. And this just looks like a mistake. It makes little sense in practical terms (i.e., the release of one figure and then the arrest of the other). Moreover, the explanations offered for this — where the difficulty is noted — often lack plausibility.

Rapske (1996 [1994], 238), following Kümmel and others, suggests that various figures assisted and stayed with Paul during his house arrest on different occasions and thereby merited the moniker at different times (see Acts 28:16, 30). But first, nothing suggests here that Paul is under house arrest; second, he is not in Rome (as in Acts); and third, such figures are hardly thereby actually imprisoned and so accurately described as fellow prisoners.

Some commentators have argued, rather differently, that the designation is metaphorical (so Wilson 2005, following Moule and ultimately Lightfoot), but this is an implausible reading in its own right. Paul’s sun- compounds elsewhere are never metaphorical but fundamentally concrete. Moreover, a metaphorical meaning is somewhat opaque. In what sense is a Christian coworker a “fellow prisoner” metaphorically? Paul’s gospel speaks of the very opposite, that is, of the liberation of its participants from any slavery or impediment. Nevertheless, the line of interpretation opened up by Lightfoot and Moule is ultimately helpful.

They note that the word used did not, strictly speaking, reference a prisoner in a straightforward sense; it denoted a “prisoner of war,” or POW. (“Prisoner” was denoted by δέσμιος and, more rarely, by δεσμώτης, from “chain” or “bond” or “fetter” [δεσμός]; αἰχμάλωτος, however, denoted someone captured during a conflict.) Hence, Paul’s use of the word αἰχμάλωτος in Colossians 4:10 and Philemon 23 did not necessarily imply a shared imprisonment, as its application in Romans to Junia and Andronicus confirms (Rom 16:7). It denoted, rather, the special status of previous imprisonment, although here described in the apocalyptic terms of a war between the gospel and the evil powers opposing it in the cosmos (this being the truth of the metaphorical reading suggested by Moule). So this signifier functions much as the designation “fellow soldier” does elsewhere for Paul (συστρατιώτης). Such a figure is no longer in the army or serving in a war but is honored by that recollection, the moniker now being interpreted additionally in terms of Christian service (and this is the characterization of Epaphroditus in Phil 2:25, and Archippus in Phlm 2). The result of this realization is that we learn rather less from the data concerning Epaphras and Aristarchus than we might first have thought we did. It seems that they both have been imprisoned at some time because of the gospel. And clearly, no contradictions are now apparent in the texts, since this is quite possible.

However, we do now have to insert an imprisonment into our previous narrative concerning Epaphras, although there are several appropriate locations for this. It is striking that he has been incarcerated already for his new piety, but this is not necessarily impossible. He could have been imprisoned when he converted at Paul’s location. And he could have been detained on his return to Colossae, or on his return to Paul’s location, and both scenarios would explain why he is not accompanying the letter back to his hometown (if we still need to). It seems unlikely that Aristarchus and Epaphras were both actually imprisoned at the time when Colossians and Philemon were written; we would expect Paul to be a little more consistent with his designations if this were the case, and also a little more pointed (i.e., not use the metaphorical reference; Paul never describes his own current incarcerations in these terms). Ultimately, then, I tilt toward an earlier Colossian imprisonment for Epaphras, since this helps to explain his continuing presence with Paul when Colossians was written and dispatched. So this possible inconsistency between Colossians and Philemon seems well explained. And another possible anomaly in the greetings is also worth noting in passing.

The greetings in Colossians mention in 4:11a “Jesus/Joshua who is also called Justus” (καὶ Ἰησοῦς ὁ λεγόμενος Ἰοῦστος), but he seems to have dropped from sight in Philemon (see only Μᾶρκος, Ἀρίσταρχος, Δημᾶς, Λουκᾶς, οἱ συνεργοί μου). Is this another telltale slip by a pseudepigrapher? Not necessarily, if we suppose that Paul used only this person’s first name in Philemon 23b, “Jesus/Joshua,” and that this was subsequently folded by reverent scribes into an extended designation for Christ, thereby erasing the reference to the figure of “Jesus/Justus” (see Ἀσπάζεταί σε Ἐπαφρᾶς ὁ συναιχμάλωτός μου ἐν Χριστῷ Ἰησοῦ). Any emendation here is conjectural, being unattested in the manuscript tradition, but seems highly plausible (i.e., Ἀσπάζεταί σε Ἐπαφρᾶς ὁ συναιχμάλωτός μου ἐν Χριστῷ, Ἰησοῦς κ.τ.λ.), a view that Raymond Brown (1997, 614 n. 31) notes in passing. This conflation would have been assisted by the μου just three words previous, which might have suggested the genitive rather than the nominative ending for Ἰησοῦς. In addition, the characterization of Epaphras in Colossians 4:12 varies, with the longer reading — “of Christ Jesus” — possibly reflecting the emendation of Philemon 23b. Alternatively, if original, it might have prompted or reinforced that emendation. So this further potential anomaly seems explicable. But other data might still cause trouble for our developing reading, which roots Colossians and Philemon in the early stages of an Asian mission.

(iv) Romans 16:5 suggests that Epaenetus was Paul’s first convert — literally, “first fruits” — in Asia (see 1 Cor 16:15). Moreover, we know of Epaenetus only in conjunction with Prisca and Aquila. He seems to be part of their house gathering at Rome when Paul writes Romans in the spring of 52 ce (16:3-4). And it seems plausible to infer from this data that Epaenetus was converted through some connection with Prisca and Aquila and so most probably at Ephesus (1 Cor 16:19). But this would preclude earlier conversions of Epaphras and Tychicus in Asia, as supposed by Colossians and our developing reconstruction (later tradition identifying Tychicus with Asia, almost certainly unexceptionally; see Acts 20:4). That Paul would have been speaking in local, regional rather than broader, provincial terms about Epaenetus’s Asian origin, thereby avoiding this conundrum, also seems unlikely, given his usage in 1 Corinthians 16:19.

But there is insufficient data here to build a decisive case. Epaenetus might have been part of Prisca and Aquila’s house gathering in Rome and a product, earlier on, of their work in Ephesus, but he could have been living with them in Rome simply as a Pauline convert enjoying their hospitality. Or he might simply have been named in Romans immediately after them by way of association with the Asian mission and not have been staying with them at all. We should infer that he was converted prior to Epaphras in Asia, although he no longer seems to have been with Paul when Colossians was written. But Apamea was in Asia, along with any settlement to the west of it, so he could have converted in one of those locations, where Paul was imprisoned. And his presence in Rome as attested by Romans 16:5 attests directly to his mobility. Tychicus might have converted subsequent to Epaenetus in Asia as well, or he might have converted somewhere else, outside Asia. So resolving this challenge thickens our description concerning the early Asian mission helpfully, if we add the conversion of Epaenetus to Paul’s current incarceration in addition to the conversion of the Colossian slave Epaphras, rather than undermining its plausibility. Similar considerations hold for Tychicus. Moreover, the existence of these congregations in the Lycus valley helps us explain Paul’s otherwise somewhat opaque plural in 1 Corinthians 16:19, written the following spring: Ἀσπάζονται ὑμᾶς αἱ ἐκκλησίαι τῆς Ἀσίας. And at this point one last query remains.

(v) Both Colossians and Philemon are silent about the collection for Jerusalem, a major project that Paul is currently administering. According to our developing scenario, he has just instructed the Galatians about its prosecution (during a visit) and will shortly engage in a long and complex negotiation with the Corinthians about the same, will gesture toward it subtly in his letter to the Galatians, and will mention it at its conclusion in Romans. Does Paul’s silence about this important undertaking in Colossians and Philemon suggest that they were not written at this time?

This inference is doubtful. Paul’s letter to the Philippians attests to the fact that he does not always refer to the collection during this period. Its mention is helpful — if not critical — for sequencing when it does take place, but the converse does not apply. That is, it does not follow from the silence of a letter concerning the collection that it was not composed during this period. Moreover, that Paul would resist introducing a request for money into letters written to gatherings who had not yet set eyes on him is entirely understandable. The ancient world was full of charlatans (see Anderson 1994); hence, one of Paul’s most constant struggles was the battle for perceived financial integrity, a struggle discernible from his earliest correspondence to the Thessalonians (1 Thess 2:3, 5). So the silence concerning the collection in Colossians and Philemon is not only not a difficulty; in these circumstances, it is to be expected.

It seems, then, that any difficulties arising as we insert Colossians into our developing frame alongside Philemon are more apparent than real. They are worth exploring, and some, in their resolution, have deepened our knowledge of the original situation, but none are fatal. And as a result, our earlier judgment that Colossians was authentic has been strengthened; a web of overt and subtle connections ties it into our existing frame, which should now be augmented by its confident insertion (that is, pending the outcome of later challenges).

The existing principal sequence of letters, running through Paul’s (calendar) year of crisis, can now be expanded with the addition of Philemon and Colossians in the previous year:

// 50 //

. . . Phlm / Col . . . [PLC] —

// 51 //

1 Cor — 2 Cor — [PLP]Phil 3:2–4:3 / Gal — Phil —

// 52 //

Rom . . .

With this useful expansion of the biographical frame tentatively in place, we can turn to consider some of the weightier methodological challenges to the authenticity of Colossians — in terms of dependence and style.

2.3 Questions of Dependence and Style

(1) Dependence

A specific and quite important question of dependence clearly arises here, namely, the relationship between Colossians and the prior letter to the Laodiceans (Laod). Not much turns on this if Laodiceans is simply lost; however, if Ephesians is identified with Laodiceans, then the situation waxes in importance. In fact, a matrix of possible results exists for this relationship. But only one of these can potentially alter our developing judgment here — and this presupposes that dependence in one direction can be definitively demonstrated.30 If this option is eventually affirmed — that Ephesians demonstrably precedes Colossians and is inauthentic — then we will return and revise our judgment concerning Colossians. But in view of its unlikelihood, we can safely postpone consideration of this issue until the letter to the Ephesians is assessed in detail in §3. All the other options leave the question of Colossians’ authenticity open.

|

Ephesians |

Ephesians |

|

|

Ephesians |

Colossians |

Colossians |

|

Ephesians |

Colossians |

Colossians |

But this still leaves other possible instances of dependence in Colossians unaccounted for.

Recently, Leppä (2003), looking back to a classic analysis by E. P. Sanders (1966), has argued that Colossians is inauthentic, because of its overt dependence on various indubitably authentic Pauline letters — a significant suggestion, because it is made independently of any judgments concerning Ephesians.31 But we have already entered a strong objection concerning this type of inference, and must introduce a caveat to Leppä’s argument as well.

Paul evidently kept copies of his letters; the letters circulated through multiple congregations (see Col 4:16); and copies seem to have been made and studied in those locations. So he seems to have echoed his letters in various ways within further correspondence when he felt the need to do so.32 Second Thessalonians 3:8 provides an especially good example of a small specific echo when it quotes but also pointedly reapplies 1 Thessalonians 2:9 (2 Thess is discussed in Leppä 2006; and here in ch. 4), and we have seen the presence of broad structural similarities between 1 Thessalonians and 1 Corinthians as well (also in ch. 4). Hence, the mere fact of dependence has already been shown to be unremarkable, as Sanders in effect concedes. So this aspect of Leppä’s case can actually be granted, but it suggests nothing further in terms of authenticity — the false inference in her analysis (i.e., dependence necessitates pseudonymity). Indeed, this was our principal objection to this line of reasoning earlier. But a caveat ought to be entered here as well.

Leppä’s data is indecisive even with respect to sequencing Colossians, since all of the putative echoes that she assembles can be explained plausibly in the reverse direction, as the echoes of Colossians by later Pauline letters. That is, echoes of undisputed letters appearing overtly later in Colossians would break apart our existing frame, pushing Colossians later in the broader letter sequence at the least — an important result. But Leppä never demonstrates that the echoes must proceed in this single direction, from another letter to Colossians, thereby falsifying our frame. Indeed, demonstrating direction or causality is a common problem in the analysis of perceived dependence. Leppä assumes the inauthenticity of Colossians and so does not feel the need to address this problem of reversible dependence, but it is a critical question for our framing project.

Having said all this, it is important not to overlook the hurdle that advocates of authenticity face in this relation, namely, the supply of plausible contingent accounts of any identified echoes, something that was arguably done here on a small scale for 1 and 2 Thessalonians, and on a larger scale for the echo of 1 Thessalonians by 1 Corinthians.33 But arguably good contingent accounts can be supplied of the echoes that Leppä and others have detected between Colossians and the undisputed Pauline letters.

So, for example, Sanders argues that

(i) Second Corinthians 4:4, Romans 1:20, 1 Corinthians 8:5-6, and Romans 11:36 are echoed in Colossians 1:15-16; but Sanders’s second instance here (Rom 1:20) is forced, and the others are arguably understandable echoes of an important preexisting hymn or confession;

(ii) Second Corinthians 5:18, 1 Corinthians 8:5, and Romans 5:10 are echoed in Colossians 1:20-22a; but the front end of this set of echoes in Colossians is again explained plausibly by the hymnic origin of that material, and the second is a plausible reprise of a key Pauline theological narrative — the reconciliation of a hostile humanity (and Sanders underplays the presence of this discourse elsewhere in Paul, omitting other parallels in 2 Cor 5:16–6:1);

(iii) First Corinthians 2:7, Romans 16:25-26, and Romans 9:23-24 are echoed in Colossians 1:26-27; but this appeal to “the revelation schema” informed by Jewish Wisdom traditions is again arguably unremarkable for Paul (i.e., because it is so important substantively), and any leverage from the doubtful Romans 16:25-26 is questionable; and

(iv) Romans 6:4, Romans 4:24, Galatians 1:1, Romans 6:11, and Romans 8:32 are echoed in Colossians 2:12-13; but Romans 8:32 is a false parallel, and Galatians 1:1 vestigial, leaving overtly traditional verses (Rom 4:24) and material (the Rom 6 account of baptism) in close relation to a baptismal discussion in Colossians 2.

In sum, Sanders’s echoes are less impressive than they first appear, and arguably, they combine to tell us only what theological motifs are important to Paul — useful information in another setting, to be sure, but not here.34 Hence, we will set this interesting challenge to one side for now and proceed to the next challenge to the authenticity of Colossians, namely, its much-touted difference from the authentic letters in terms of style. Of course, some of these questions of dependence will have to be revisited in earnest during the assessment of Ephesians, when we will have to consider the significance of the virtual web of intertextuality that holds between Ephesians and Colossians, and with the undisputed letters in turn, and will have to at least try to determine the flow of the obvious dependence in view. But that discussion can wait.

(2) Style

The stylistic challenge to the authenticity of Colossians began as early as 1838, when it was one important aspect of Ernst Mayerhoff’s case for the letter’s pseudonymity. And it reached an apparent climax with the soul-destroying tabulations of Walter Bujard in 1973. Thus, Ehrman cites Bujard’s analysis and comments that it is “widely thought to be unanswerable” (2013, 175). But is it?

Bujard’s data is impressive. However, it needs to be measured against the statistical and (where relevant) computer-assisted evaluations of style that were first noted in chapter 4. And we should recall the initial methodological observation made there — that mere tabulations of difference are, when uninterpreted, largely meaningless. All of Paul’s undisputed letters contain stylistic differences from one another, and “style” itself is an immensely complicated and largely undefined notion — a combination of dozens, if not of hundreds, of different features of the language used in a given set of texts. So interpreters of Paul need to be very careful, first, not to “cherry-pick” the data, tabulating variables that indicate differences between undisputed and disputed letters, thereby omitting those variables that either are unremarkable in a disputed text or that suggest the oddity of an undisputed text. And second, they need to avoid assuming blithely that an instance of difference is an automatic marker of alternative authorship, developing pseudonymous readings in the light of this conviction.

Both problems are apparent in Bujard’s analysis and in those like it. Hence, we need to ask, are tabulations of difference like his helpful at all? Is style a meaningful element in this debate? And we need to turn in response to those who know how to evaluate the meaningfulness of differences appropriately, something that ought to take place in the standard statistical sense, that is, in terms of distances from the mean for given variables in relation to the measurable standard deviation of a sample. And I would suggest that Kenny’s older analysis (1986, esp. 27, and 117-18) remains helpful in this regard.

It seems quite important that after tabulating 96 stylistic features and then correlating them, in order to assess their significance, Kenny concludes that the author of the Pauline corpus was extremely versatile stylistically. Without this observation, his and most other tabulations simply collapse into absurdity (i.e., the undisputed letters prove incommensurate). Once this versatility has been acknowledged in stylistic terms, only Titus “must be under suspicion” (1986, 95-100, quoting from 97). The sum of the coefficients (although he notes that they are not, strictly speaking, “additive”) also generates an indicative ranking of the letters in terms of their fit with one another, that is, in terms of cumulative differences. So, in descending order of “comfort”: Romans, Philippians, 2 Timothy, 2 Corinthians, Galatians, 2 Thessalonians, 1 Thessalonians, Colossians, Ephesians, 1 Timothy, Philemon, 1 Corinthians, Titus. In addition to the difficulties of Titus, the relative comfort of 2 Timothy and discomfort of 1 Corinthians here are noteworthy, not to mention the locations of Colossians and Ephesians as more “comfortable” than 1 Corinthians and Philemon.

In short, the calculations of Kenny directly contradict the significance (not the fact) of Bujard’s tabulations, and of those like them. The latter are unreliable indicators of significant differences between the style of Colossians and the stylistic characteristics of the rest of the Pauline corpus. Can we go further than this, however, drawing especially on the more recent computer-assisted evaluations of stylistic data in Paul to generate some more aggressive insights about authorship?

I would suggest — tentatively — that at present we cannot, although we should not rule out the possibility that more refined methods and experiments will deliver more decisive results in the future. (Indeed, I expect that they will.) But the most sophisticated analyses we currently possess — Neumann, Mealand, and Ledger — in my view lack decisiveness. Although they do seem to be able to discriminate successfully between significant blocks of material within the NT (like the Gospels, Acts, the book of Revelation, and the letters; see Ledger 1995, figs. 3 and 4, pp. 88 and 89), when they turn up the focus, so to speak, and generate plots of the Pauline letters alone, the resulting results lose plausibility (see figs. 5, 6, and 7, pp. 90, 91, and 92; also Mealand 1995, fig. 8, p. 83; and the plots below, unpublished but which Mealand kindly shared with me in personal correspondence). It becomes very difficult to detect whether the plots generated are supplying meaningful information or mere noise. So, for example, Ledger concluded rather confidently that 1 Thessalonians is doubtfully authentic, because it plots close to Ephesians, Colossians, and, to a certain degree, the Pastorals. But this is unlikely to be a meaningful result. Rather, it calls his plot into question. And the plots for Romans and 1 Corinthians are as widely spread in Mealand’s analyses as the plots for Ephesians, while only the sample drawn from the first half of Ephesians tends to be an outlier.35

I suggest, then, that we must wait for the next generation of stylometric analyses for more decisive results at the front end of the framing process — and perhaps this is not surprising. Stylometrics has always had more success identifying an author if it already knows that one of two or more authors is responsible for the text in question.36 And this indicates the correct location for this method within framing in terms of its more positive suggestions — later on, as a corroborative contention. That is, if the pseudonymity of any Pauline letters can first be established with some confidence on traditional grounds, such as demonstrable anachronism, then stylometric analyses can be introduced under this control and potentially corroborate the judgment. But this analysis cannot be pursued yet. It is a far more difficult business to determine whether multiple authors are present within a given sample, especially given that the sample size is not particularly large (and this is exacerbated in the case of Paul, because he is not working in English, or even in a Romance language, the language(s) on which most computer-assisted analyses of style are premised).