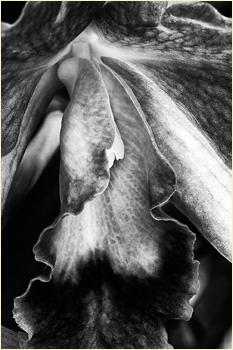

The jutting lips (petals) of a hybrid orchid (Cattleya sp.)

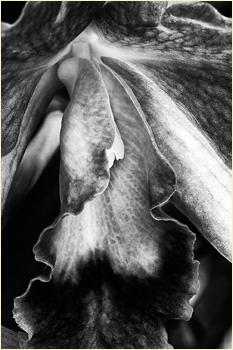

The jutting lips (petals) of a hybrid orchid (Cattleya sp.)

Flowers grown halfway around the globe can be yours, shipped to your doorstep with next-day service in most countries. The virtual image on your computer screen today becomes your reality tomorrow when your flowers arrive. This is globalization in action with a huge international impact. Time and space have been altered in a way nature never planned.

Millions of flowers move across continents every day as freight aboard aircraft and inside eighteen-wheeled semitrailer trucks. In a year, billions of flowers are quickly moved from country to country, from growing regions to auctions, packers, and distributors, then on to their final retail destinations. Most of the fascinating journeys of these cut blooms go on out of view of the public, a little-told story in modern global commerce.

Not long ago, Americans visited local family-owned florist shops, making all of their purchases in person, chatting with shop owners or knowledgeable clerks about flowers available that season, or which ones were the freshest. Historically, the majority of cut flowers Americans purchased were grown on US soils on flower farms or inside greenhouses, especially ones in the San Francisco Bay region, coastal valleys of California, and parts of Florida. Today, customers still visit florist shops, but their purchases seem quaint in the rush to order flowers online for fast delivery or as impulse purchases at the supermarket or big-box stores such as Lowe’s or Home Depot. Now, the single-stemmed cut flowers that each of us buys are largely grown and shipped to us from overseas, from growers and packers in Latin American countries. In what seems to be the cultural mantra for American shoppers, not only do we want our flowers right away, but they’d better be fresh, must look absolutely fantastic, and be available at ever-lower prices.

Large-scale producers, or affluent hobbyists, grow flowers under glass or plastic films in greenhouses because their plants, especially “tropicals,” thrive under these warm and humid conditions as if they were still growing on their native soils in tropical forests. Greenhouse production of cut flowers (spring bedding plants, annuals such as petunias and marigolds, are mostly raised in US greenhouses) is an expensive commercial option, not for the faint of heart. Whenever possible, it costs less to grow bedding plants or cut flowers outdoors using traditional row-crop agricultural methods. The largest growers of cut flowers were once located in California’s coastal and central valleys, and scattered along the Pacific Rim as far north as coastal Oregon and Washington. Today, large farms for cut flowers continue in California, but they are remnants of a once-great American agribusiness. Like so many other US industries, our cut-flower farms have also moved offshore. The domestic flower industry could not compete with more favorable corporate tax rates and cheap labor. Flower-growing for cut-stem markets moved toward the steamy and hot equator. Here are nutrient-rich volcanic soils, a favorable year-round climate, and laborers willing to work under harsh conditions and at wages unacceptable to most US citizens.

Among Latin American cut-flower-growing countries, Colombia leads the way, followed by Ecuador and Costa Rica. Colombian-grown flowers dominate US markets, with roughly a 70 percent market share, over $1 billion in stems sold each year. Amazingly, this billion-dollar business sprang from a 1967 botany term paper written by Colorado State University graduate student David Cheever. In his study, entitled “Bogotá, Colombia as a Cut-Flower Exporter for World Markets,” Cheever extolled the virtues of a former-lake-bed savanna, near the small city of Facatativá, close to Bogotá at eight thousand seven hundred feet above sea level, and 320 miles north of the equator. In his business plan, the rich soils, equitable climate, and nearly consistent twelve hours of daylight year-round were perfect for growing a crop that everyone wanted 365 days a year: cut flowers on long, straight stems. At higher elevations in the tropical Andes, the moist and cooler climate mimics conditions favored by domesticated plants descended from temperate species. Exporting roses to other countries would probably be more profitable for farmers in this mountainous region than growing and selling apples, pears, and strawberries in the hot valleys below.

In 1969, while his friends were likely partying at Woodstock, Cheever and three partners together invested $100,000 in a new business, launching their flower-producing dream start-up company, Floramerica. They used assembly-line production methods and modern shipping-by-air methods to bring their ultraperishable products to US and other markets. Floramerica started by growing carnations in greenhouses on that savanna near Bogotá’s El Dorado International Airport, with a short three-hour flight north to Miami. The Californian cut-bloom industry would never be the same again. In 1991, the US government suspended import duties on Colombian flowers, hoping to limit coca-shrub farming and the cocaine trade in violence-ravaged Colombia by creating decent-paying jobs outside the pervasive drug cartels. The results were quick and decisive for Colombia, but essentially wrecked US floral-stem production on California farms and for other regional US growers.

Thus began an economic revolution in Colombia, one fueled by beauty, not addictive illegal drugs. In 1971, growers of cut flowers in the United States produced 1.2 billion blooms (carnations, chrysanthemums, and roses), while the country imported a mere 100 million cut flowers. By 2003, the floral-stems balance had reversed. That year, the United States grew a scant 200 million cut stems, while it imported a staggering 2 billion, all the desirable favorites. Flowers had become a global commodity not unlike DVD players, flat-screen televisons, or tablet computers.

Today, visiting any of the cut-flower producers in Colombia, Ecuador, or Costa Rica is an eye-opener if you are accustomed to a patch of flowers growing in your home garden. This is indeed big business in blooms. Ecuadorian flower farms near Quito are typical of the large-scale South American flower growers. You see ramshackle greenhouses with clear-plastic films stretched and stapled tightly across wooden frames, but high-tech flower factories are inside. Rows of workers, usually women and girls, stand along opposite sides of slowly moving conveyor belts. If roses are being packed, the workers first remove the thorns using chain-mail gloves or special tools. Diseased, blemished, or torn leaves are removed along with substandard flowers. Stems are trimmed to standard lengths, and the stalks once again placed on the moving belt for the next worker along the line. Eventually, the floral bouquets are dunked, usually by men, into foul-smelling metal, fifty-five-gallon drums of fungicide, then shaken off or hung briefly to drain. The “tank mixes” may include a veritable soup of harsh chemicals, including floral preservatives. These are clearly not organic flower operations. In the recent past workers used substandard respirators or no protective gear while handling the now-toxic flowers, but conditions are gradually improving for the workers.

For the women who do most of the trimming, sorting, and packing of the cut blooms, these labor-intensive jobs lead to debilitating repetitive-stress injuries along with exposure to dangerous agricultural chemicals. Many of these chemicals are now banned for use in the United States or used under limited conditions and with adequate protective equipment. Greenhouse and field conditions on the South American flower farms are getting better. Many of the producers now provide fully protective clothing and respirators, along with health benefits and on-site recreational facilities or child-care services. Still, the work is harsh for the largely underpaid flower workers, not substantially different from the backbreaking routines that migrant workers experience while harvesting and boxing vegetables in the Imperial Valley in Southern California.

Once wrapped and packed into their boxes for shipping, the Ecuadorian cut roses and other blooms are briefly moved into cold rooms. From there, the flowers are loaded into refrigerated trucks and driven to the nearest airport. There, workers stack the thousands of flower boxes onto wooden pallets that are then shrink-wrapped and loaded by forklifts into the cargo holds of waiting jumbo jets. The flowers are the only passengers inside these stripped-down aircraft on their brief journey to Miami International Airport. It will, however, be several days before the thirsty flowers will again have water.

The tarmac at Miami International Airport is a busy place for passenger aircraft with their belly cargo, in addition to the frantic activity of the dedicated air-freight haulers. More than a hundred international air carriers, including the major Latin American airlines, have made Miami their main or only port of call. The cargo division is far from the gates and terminals filled with scurrying passengers. Cut flowers arrive inside aircraft with covered windows and no visible corporate logos. The planes have only two pilots, a flight engineer, no flight attendants, and maybe a coffeepot, with no seats or amenities for passengers, since there aren’t any. Here, the cargo pays. Every day, more than a dozen aircraft may arrive, every one jammed full of fresh flowers. Around Valentine’s Day, that number can increase to a frenetic fifty daily flights from South American airports.

The big cargo aircraft begin landing around four o’clock in the morning. Once the cut flowers are unloaded from inside their contoured aluminum containers, the ULDs (“unit load devices,” each holding about 160 cubic feet of cargo), they are whisked to refrigerated coolers inside massive transit sheds, for unpacking, sorting, processing, and final inspections, prior to the next phase of their journey to markets and waiting flower lovers.

The inspectors at the Miami airport are Department of Homeland Security employees, and they are all-business, with few smiles. The inspectors shake out sample bouquets onto white backgrounds. If even one dead insect falls out or a fungal spot is found on a flower or leaf, the entire shipment can be rejected (tossed into a Dumpster or similarly disposed of) or ordered fumigated, expensive costs all borne by the original owner and shipper. Because these cut flowers are not intended for human consumption, they are not tested for illegal pesticide residues. The inspectors also examine the sampled boxes for contraband (they are automatically X-rayed). This doesn’t happen much anymore, but in the past even romantic Valentine’s Day red-rose stems were once hollowed out to conceal cocaine or other illegal drugs. Such commerce will always find a way.

By the early morning, many of the flower trucks are already speeding along Florida highways, especially north on Interstate 95, past its intersection with I-10, then continuing along the Eastern Seaboard to New York City’s flower district, and other populous Eastern-city destinations.

Americans buy about 4 billion cut stems a year, amounting to 10 million flowers every day. About 88 percent of the several billion cut flowers imported to the United States arrive by air at the Miami airport en route to their final destinations. Additional air-cargo shipments of fresh flowers are handled at Los Angeles, Boston, Chicago, and New York airports, but not nearly as many as at the flower hub that is Miami. In the first two weeks of February an extra 12 to 15 million roses pass through the Miami airport every day.

The number of globe-trotting blooms making up the modern cut-flower trade is staggering to consider. Globally, about 15 billion cut flowers make their way from growers to sellers every year, shipped by air or by trucking lines and independent haulers. By 2003, cut flowers and floriculture had grown to become a multibillion dollar industry worldwide, growing by about 6 percent annually.

It is important to distinguish between the domestic and foreign cut-bloom industry (largely roses), and the seasonal potted and bedding-plant commercial trade. Some US bedding plants travel here from Europe, through Holland, but the majority are grown in the United States by the largest wholesale nurseries. People, especially those living on the East Coast, delight in buying potted hybrids, especially primroses, hyacinths, cyclamens, tulips, and daffodils, early in the season, almost before the ground has thawed. These spring beauties help to relieve the common psychological malaise of “winter sickness,” with everyone hoping for sunshine and warmer weather, a time to plant. Many of these inexpensive potted plants are annuals such as pansies, tufted violas, petunias, and verbenas. They are sold as throwaways and are headed for the Dumpster after they bloom or die from improper care. Also, no florist sells begonias or cyclamens as cut flowers. Their lives are too short and they fall apart when handled. Apparently, turnabout is fair play, since Europeans now buy potted native American plants, especially our cacti, but these American/Mexican succulents began their lives in Israeli kibbutzim before being exported to Europe.

Meanwhile, messages bombard us by Internet, television, radio, newsprint ads, and end-counter displays in our local nursery or garden center, encouraging us to buy small potted shrubs with buds and blooms in advance of their actual blooming season. These potted beauties are forced into blooming in greenhouses or warm outdoor locations, then shipped to nurseries and hardware stores. Why? Spring gardeners are eager for anything flowering at the onset of spring. Favored plants seem to be late-winter pots of forced bulbs, forsythias, lilacs, and azaleas already in advanced bloom. Today, who has the time or patience to wait for Mother Nature? This same “florific” anticipation occurs again in late summer when we can’t resist budding and blooming pots of “autumn” chrysanthemums from various purveyors.

Nurseries get in on this advance-bloom psychology as well. Go to any dedicated nursery, or hardware-store-chain nursery-sales area, in the spring. Take note of what is for sale, and what is blooming. Here are rhododendrons, azaleas, forsythias (in the Midwest and Eastern US), lilacs, and many others. These plants are in glorious full bloom a full month before their buds should have expanded into flowers. This isn’t early blooming caused by global warming; it’s a fact of plant-industry marketing ploys, planting the seeds of hope and desire in our minds.

Dutch businessmen and women are consummate flower traders and dealers. Just as in the seventeenth-century tulipmania, when the fervent desire for fancy tulips seized wealthy speculators in a bubble market, today the world turns to Dutch auctioneers for buying and selling their prized blooms. The Dutch are the world’s leading flower exporters. Europeans are more familiar with the Dutch flower business than Americans—since only about 5 percent (roughly 200 million) of US flowers pass through Holland—due to the unique business practices and traditions of the Dutch auction houses. There isn’t an easy way to know the provenance of cut blooms sold at your favorite market.

In Europe, the Middle East, and Asia, the majority of cut flowers and bulbs first pass through Amsterdam’s Schiphol Airport. From the airport, they enter the massive Dutch auction and computerized bidding system before resuming travel to their final destinations in many countries. Flowers sold in the Dutch auctions may have come from as far away as Colombia, Ecuador, Costa Rica, Ethiopia, and several European countries, along with Israel, Kenya, South Africa, or Zimbabwe. Flowers can spend up to a week transported through various warehouses, airports, and often the Dutch auction houses, before reaching their final destinations, looking almost as fresh as the day they were harvested somewhere far away. Looking at why this happens, and its history, makes for a fascinating story, even if you aren’t a fan of plant auctions.

The Aalsmeer flower auctions, close to the Schiphol Airport, are now world famous but had simpler beginnings. They were started in 1911 by a group of Dutch bulb and flower growers meeting in a café. They came up with the idea of holding an auction they called Bloemenlust as a way to gain more control over the prices they got for their flowers and how they were sold. Many auctions followed, but by 1968 the largest became known as Bloemenveiling Aalsmeer. By 2008, the Aalsmeer flower auction had merged with the auctions of Naaldwijk and Rijnsburg and became FloraHolland. Not only a major auction center, Aalsmeer also serves as a sort of regional distribution center, where flowers get rerouted by air to destinations around the world.

The immense FloraHolland building in Aalsmeer encompasses a staggering 10,750,000 square feet and is the largest single building, by its footprint, in the world. Its proximity to the Schiphol Airport, only eight miles away, makes it an ideal location for the daily auctioning of many of the world’s blooms. The facility whirs with frantic activity, starting before dawn, nearly every day of the year. Truckloads of flowers unloaded at Schiphol begin arriving as early as midnight, and bidding starts before dawn. The nearby city of Aalsmeer, with a population of only twenty thousand, provides a workforce up to twelve thousand to move, buy, and sell all the flowers in the FloraHolland complex. Around 21 million flowers change hands here daily. The selling volume increases by 20 percent or more around Valentine’s Day and Mother’s Day.

Alstroemerias, carnations, roses, gerbera daisies, lilacs, freesias, chrysanthemums, and tulips are the major types of cut flowers on the auction block at Aalsmeer. Houseplants are sold here, too, including 9 million ivy plants and 13 million fig trees (Ficus). Pots of forced flower bulbs, ferns, cyclamens, begonias, and other decorative greenery for the florist trade are bought and sold, along with annuals, and bedding plants including petunias and pansies. In the FloraHolland building, hundreds of carts are loaded with flowers and stored in giant refrigerated rooms. Soon after their arrival, the flowers are graded by inspectors, getting around thirty inspections, and finally ending up graded A1 (the highest-quality blooms), A2, or B, the lowest-grade blossoms.

The cavernous building is noisy, alive with activity, as hundreds of workers shout out to one another while trying to avoid collisions amid the squeaks, creaks, and bangs that the rolling-cart trains make. Some workers stand while driving their sexy orange-and-black scooters that look a bit like Segway vehicles. Seated drivers steer electric vehicles pulling small trains of a dozen or more linked aluminum cars, each one a mobile rack holding one to seven layers of colorful potted plants or cut blooms. It seems chaotic as the flower trains make their way into and out of bidding halls scattered throughout the complex. Tourists walk, talk, and stop overhead on a network of metal catwalks, taking in the frenzied action on the warehouse floor. More than three hundred thousand international tourists visit the Aalsmeer flower auctions every year.

The five immense auction halls have tiered seating. More than a thousand wholesalers, mostly men, bid on trainloads of brilliant flowers as they move slowly by on the auction floor below, with about sixty thousand transactions daily. Everything seems to happen nonstop, as carts, people, and flowers are kept moving. Auction workers pick up a plant or bouquet at random, holding it aloft for all to see. This is called a Dutch auction, and unlike American auctions, where bidding starts low and ends high with the winning bid, in the Dutch system the auction price starts high and quickly works its way down.

A pair of huge, circular electronic wall clocks stare down upon the bidders like giant orbs. LED numerals on the clocks display the lot number, asking price, and information about the kind and quality of the flowers being offered for sale. Lots for each kind of flower appear only on one clock. The auctioneer starts the clock, and the digital lights sweep around the clockface (marked in euros, not seconds). The winning bid, actually the first bid registered, is reached long before the clock time expires. The first fast-fingered buyer to press his or her buy button has the winning bid. Dozens of transactions can be handled in under a minute. Bidders have only a few seconds to view, judge, and decide whether to buy before the flowers are moved out of the auction room and soon shipped to their new owners, often half a world away. This is an amazingly efficient way to see, move, and sell all those millions of flowers and plants every day.

Why all those flowers need to make a personal appearance on the bidding blocks near Amsterdam for Dutch auctioneers seems a bit mysterious, perhaps inexplicable to the rest of us. There are huge costs, and an immense jet-fuel carbon footprint, in transporting more than 5 billion flowers annually in and out of Holland during their quick but long-distance, jet-assisted journeys around the world. Why subject ultraperishable fresh-cut flowers, of all things, to the added time and expense of getting them to and from Aalsmeer? Why waste the extra day or more of precious floral vase life that this complex process takes? It all seems absurd. No global television, automobile, beefsteak, or brussels sprouts auctions are taking place in Los Angeles, Hong Kong, Beijing, or Manhattan. I don’t have an easy answer. Perhaps it is just a venerable and proud Dutch tradition.

It’s February 14, Saint Valentine’s Day, once again. If you’re a married man, or in a committed relationship, you better have planned ahead for your holiday purchases. Your reserved bouquet is waiting to be picked up at the local florist. If your iPhone calendar-app reminder was set for February 14, instead of the twelfth or thirteenth, you may be in deep trouble. No red roses may be available in any store. A card and a box of chocolates won’t get you out of that! Mothers and grandmothers seem to be more forgiving than flower-slighted spouses or lovers.

The biggest flower-giving day in the United States is Valentine’s Day (Mother’s Day is a distant second). A staggering 224 million roses were grown, mostly in South America, for Valentine’s Day in 2013. Almost all of these were long-stemmed, red-rose varieties. About 110 million roses are sold in the United States on Valentine’s Day each year, with men making up about 75 percent of the buyers. Since red roses signify passionate love, about 43 percent of all freshly cut roses sold on Valentine’s Day are red varieties. Another 29 percent of the Valentine’s Day flowers are roses, but colors other than red. Women also buy flowers on this day, for their daughters, mothers, and grandmothers. Some women buy and have roses sent to themselves. Sales of Valentine’s Day flowers are greatest if the holiday falls during the week, and dismal if it falls on a weekend. About $1.7 billion were spent by US consumers on Valentine’s Day flowers in 2011. Although California produces 60 percent of the roses grown in the United State each year, the majority of long-stemmed Valentine’s Day roses are imported from Central and South America. US purchases amount to more than 1 billion roses every year from overseas sources, mainly Colombia.

As we’ve seen, roses have symbolized many things over time and in various cultures. During the dynastic War of the Roses (1455–85) for the throne of England, a white rose was associated with the House of York, while a red rose stood for the rival House of Lancaster. Roses were sacred to the Roman goddess Venus, and she represented beauty, love, pleasure, and garden fertility.

Our flower-buying tastes and habits were different in the past and they keep changing today. The demand for organically grown flowers is increasing, and this has led to more growers becoming certified as organic producers. US customers now want to know if they are buying safe, organic products, especially as regards flowers imported from other countries, whose pesticide regulations may be lax or nonexistent. A significant problem for certifying organic blooms has been that the bouquet you bought at Trader Joe’s, or any other market, surely contains mixed blooms, perhaps organic flowers from California growers, along with flowers of unknown origins, or chemical treatments, from South American producers. Typically, there has been no easy way to follow the blooms from individual growers after they hit the tarmac in Miami, then make their way through the convoluted chains of distributors, resellers, and bouquet stuffers. The homeland origins of the flowers, and how they may have been farmed, or chemically treated postharvest, are somewhat mysterious and unknown to the average flower buyer.

So-called green-label flowers are one way that consumers can be more confident when making their purchases. With labels, consumers can learn about how their flowers were grown, if they were chemically sprayed, and perhaps about the seller’s concern for social and environmental justice, including if the workers were equitably paid and labored under safe conditions. Many countries have created their own certification programs, especially European ones since the mid-1990s. The Dutch program known as Milieu Programma Sierteelt (MPS) certifies growers in Africa, Asia, Europe, Latin American, and the United States. Around forty-five hundred growers are members of this program, with roughly 85 percent of flowers sold in Aalsmeer now rated by MPS officials. Switzerland has its own certification agency, the Max Havelaar Foundation, and in the United Kingdom the watchdog organic-certification organization is the Fairtrade Foundation.

The United States has come around somewhat late to implementing flower certification. Things started to change in 2001 when Gerald Prolman entered the market with his Organic Bouquet brand of green-label flowers sold online. Working with SCS (Scientific Certification Systems), a group eventually developed a national ecofriendly flower-certification procedure and identification label: Veriflora. The certification by Veriflora is a big deal now, with key, large industry players including Delaware Valley Wholesale Florist (one of the top US wholesalers) and Sierra Flowers (in Canada) using certifications.

Even the South American producers have moved ahead with certification programs. Nevado Ecuador now has a line of organic roses, with the added bonus that they have the elusive fragrance you expect roses to have. The marketing campaign by Nevado Ecuador includes the slogan “Roses with a conscience,” setting them apart from roses from other growers. Thus, it has become easier to recognize and buy organically produced blooms at food co-ops, certain florists, and even some retail markets. No doubt flowers certified as organic will increase in visibility and market share in the coming years, especially since Veriflora and Organic Bouquet have pioneered the way. Consumers, at least some, now expect to find organic blooms as a buying alternative, just as with produce in your local supermarket.

It’s difficult to predict what technological or marketing surprises may be in store for US flower buyers, or flower lovers around the world. Today, you can order fresh flowers online at Amazon.com and from other suppliers and have them delivered in as few as one or two days. My guess is that by about 2018, within sixty minutes of completing your online order with Amazon Prime, a drone aircraft—a speedy, agile, little octocopter—might just land on your front sidewalk, deliver a small bouquet of flowers, or a boxed corsage plus chocolates, then speed away. What your dog might think of this, I have no idea.

Other flower producers in different regions around the globe, especially Africa, are also entering the market, and that will change the dynamics of how and where we get our flowers. Farmers in Yunnan, China, are developing cut-flower farms and are exploring global markets for exports. In Dubai, a new plant and flower auction, the Dubai Flower Centre (DFC), opened its doors in 2005, focused on the rising demand for luxury flowers in the Middle East. If the tax-free Gulf emirate becomes a floriculture logistics air hub, it might just prove to be a thorn in the side of the Dutch.

Since the DFC opened ten years ago, what has happened? Not surprisingly, with local oil revenues, this extensive luxury-flower market and distribution center has unfurled like the petals of its costly blooms. The Dubai flower market’s auctions are different from their cold, stark forebears in gray, overcast Holland. Dubai has become a global city, a business and cultural center of the Middle East, as well as a famous playground for celebrities and the ultrawealthy.

The DFC is located on the grounds of the Dubai International Airport. Over 130 airlines make daily stops here, connecting to at least 220 cities around the world. The Dubai flower brokers are emulating the Dutch, but also innovating and reinventing the flower business in their own way. Here you will find one-stop shopping for local and international buyers, for traders, producers, and exporters. The DFC advertises itself as a transshipment center for “cool chain processes” that safeguard the quality of freshly cut flowers. This is achieved via the highest technology, with strict temperatures and atmospheric controls from the time flowers are unloaded. There are few if any breaks in the supply chain that might negatively affect flower vase life. Here also are controlled-atmosphere storage facilities for fruits and vegetables, prior to their distribution and sale.

The center excels in consolidating shipments and repackaging, along with the value-added services of bouquet-making. Eventually, the facility will be fully automated with flower-sorting robotics and quick turnover in and out of the center. Its initial capacity to handle 150,000 tons of flowers annually (along with perishable fruits, vegetables, and foilage) may eventually exceed 300,000 tons (compared to Schiphol’s 736,608 tons). Ultimately, this center could serve the needs of over 2 billion flower-buying customers.

Consider for a moment that underneath the seats and flooring of your next international flight, commercial floral shipments may be additional passengers en route to Dubai, Holland, Miami, or another destination. Cut flowers have truly become items of globalized commerce, now removed from nature and their countries of origin, but playing ever-important roles in our daily lives.