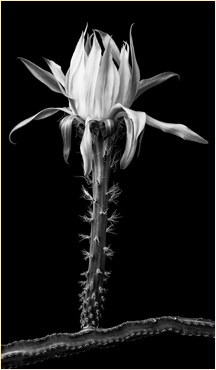

Queen-of-the-night cactus bud (Peniocereus greggii) opening after sunset

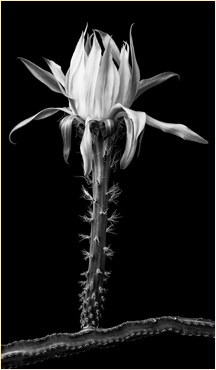

Queen-of-the-night cactus bud (Peniocereus greggii) opening after sunset

A chef wields culinary forceps, arranging blue and yellow, delicate Johnny-jump-up flowers, along with brilliant orange nasturtium petals, on each plain white plate, sticking them to an encircling line of spiced béchamel sauce. Rose petals and nasturtium blossoms are also sprinkled into the arugula and mesclun (baby greens) salad. Shimmering from within the ice cubes in water glasses are delicate blue and white, starlike borage blossoms (Borago officinalis). The herbed butter on the table was made with the diced flowering heads of purple chives and the tiny, blue petals from chicory flowers. The cocktails were garnished with colorful blossoms of snapdragon and hibiscus. Innovators of modern cuisine are having fun using flowers as garnishes to add or complement flavors, arranging and decorating foods to enhance their aesthetic appeal.

In this century, cooking with flowers is making a comeback in Western cuisines. Flowers began showing up in upscale grocery stores and trendy restaurants in the first years of the twenty-first century. Unfortunately, some people remain unsure about what is an edible flower and what’s not. This is just as true for home gardeners and chefs as for restaurant patrons ready to dine. Which posy is edible and which is an appealing garnish for our eyes only?

Some American states have enacted laws regarding the use of fresh flowers in restaurants. If the flowers are displayed in a vase on your table, they are for decorative purposes only. Please don’t eat the daises. If anything floral shows up on your plate, logically it should be edible. But, ask first. Home gardeners also wonder what they can safely eat. Are the contents of our home flower beds ever toxic? Flowers sprayed with insecticides or plants fed a fertilizer containing systemic insecticides should also be a concern of potential gourmets. You need to know the prior care and culture of your flowering plants received before you snip them for the table as edible additions.

Flowers impart a range of tastes not commonly found in other ingredients. They are not true spices (except for saffron and cloves) nor major food items, but make up a unique category. The flavors of edible flowers range widely, from insipid to sweet, spicy, and piquant. Most can be eaten raw, but some blooms must be carefully cleaned and their bitter parts discarded, while others require cooking. Most dramatically, they add beauty to our foods and dining tables.

In the most remote times of early humans and our hominid ancestors, we can envision them stooping in a meadow or alongside a stream to pick and enjoy the sweetness of flowers. Along with the nectar of flowers, and honey stored by true honey bees and their social-bee relatives, these were the first natural sweetening substances known to humanity.

Typically, modern eaters do not consume large quantities of flowers during a single meal unless they are flower buds. In contrast, fully open or blooming flowers are far more difficult to gather in large quantities and aren’t very nutritious or satisfying. No, flowers are usually relegated to only the visual delights of a colorful garnish, and many stare at them on their plates wondering if they can be eaten or only admired.

Perhaps this uncertainty is the fault of modern chefs, or the lack of widely available educational materials about edible blooms. Nevertheless, edible flowers contain small amounts of tasty nutrients including sugars, proteins, amino acids, lipids, antioxidants, and various pigments. Served by themselves as “flower confetti” or in syrups or sauces, or added to salads, main hot and cold dishes, drinks, or desserts, they color our food palettes and enliven our gustatory repertoire. Even flowers of the same species can taste different depending on their growing conditions and provenance. Terroir (the influence of the geography, soils, and climate of a certain place interacting with the genetics of edible plants and animals) not only applies to wines, olive oils, and cheeses, but also to the delicately flavored flower petals used in culinary arts.

In the guise of vegetables, Americans and Europeans routinely eat many different cooked flower buds and their budding stems. Whenever you eat broccoli, cauliflower, capers, or artichokes, you are eating the unfurled flowers or flowering heads of familiar crop plants. It’s all a matter of selective breeding. Grow Brassica oleracea for succulent leaves and you get a cabbage. Breed it for fleshy, brainlike flower stems, and you get a cauliflower. Likewise, the seeds of Brassica rapa give us canola oil, while varieties bred for flower buds are sold as rapini.

When citizens of imperial Rome and other ancient Roman cities sat down to shared meals, some of them included flowers and flower parts. Famously, Romans feasted on the boiled or roasted artichoke or cardoon (Cynara scolymus) as part of their distinctive Mediterranean cuisine. The edible and choice artichoke is the large, tightly packed flowering head of a large plant resembling a thistle. This distinctively spiny garden plant was selected then domesticated from a colonizer of fallow fields first eaten by donkeys. Early Greeks on Sicily ate the young leaves and the unopened flower heads, cultivating them as early as the ninth century AD.

Wild artichoke plants were selected over millennia for their supersize buds (actually a compound structure, the capitulum: a flower stem consisting of hundreds of massed tubular flowers). These thistles came to Greco-Roman cuisine, then to our tables as the prized but curious vegetable we enjoy today. The fibrous “choke” portion (the white pappus surrounding the immature seeds) is removed, leaving the tender artichoke hearts and attached stems. These are the beloved artichoke hearts and protective bracts we eat in salads or grilled over hot coals, canned, and marinated, or slathered with delicious sauces. Sometimes they are served as a separate course or added as a prized component of an antipasto plate. Not all Romans approved of eating artichokes. The natural-history writer Pliny the Elder (23–79) called artichokes monstrosities of nature.

The buds of a prickly shrub or vine have been used since antiquity to add nuances to our salads and cooked foods. Native to the Mediterranean basin and eastward, the caper (Capparis spinosa) is highly prized for its unopened flower buds once they are marinated or salted. Caper berries are the harvested and pickled fruits of the same plant. Domesticated from wild caper ancestors at least three thousand years ago by the Romans, they are a dominant condiment, adored by gourmands everywhere. We should also admire their beautiful white, purple, and tubular flowers, but most never open, the victims of foodies.

Flavoring beverages and sweets with floral fragrances fell out of fashion in most European cookery over the past few centuries. It wasn’t always that way, though, especially in England. The good wives in the age of Queen Elizabeth I made a syrup of violet flowers to flavor cordials, and they also knew when to add cowslips (Primula veris) to flavor imported wines. When their husbands visited inns and taverns, carnations (Dianthus) were thrown into various drinks because the petals had such pleasantly spicy fragrances. Accordingly, several carnations were known as clove pinks and sops in wine.

In contrast, many desserts concocted from Turkey southwest through the Middle East and northern Africa would remain incomplete without rose water or orange-blossom water. Today, both flower waters are in such high demand they are sold commercially in shops but are usually diluted to half strength. So are boxes of the world-famous confection—Turkish delight. The pink ones are flavored with rose water. Egyptian-born food writer Claudia Roden continues to write nostalgically of flower-flavored recipes. She remembers her aunt Latifa, who made her own flower waters in a copper still. Roden writes fondly of the perfect dessert dondurma kaimak. The best versions of this frozen custard were prepared with buffalo milk, the starchy flour of wild orchid tubers (Orchis), and flavored with rose water and crystallized resin from the mastic tree (Pistacia lentiscus).

Progressive chefs, including Alice Waters, executive chef and owner of the Chez Panisse restaurant in Berkeley, California, know how to use flowers in their recipes. They have been growing special edible-flower gardens for many years, and Waters offers her restaurant patrons delicious and amazing floral works of art for their gustatory pleasure. This seems novel until we realize that other cultures use fresh flowers in a wide variety of sweet or savory dishes.

Marigold blossoms and petals garnishing a plate of sushi

Vietnamese cooks use banana flowers in a number of main dishes and salads. In several Mexican states, pumpkin and squash blossoms are sold in local vegetable markets. They are chopped up and added at the last minute to vegetable soups to give both color and the sweetness of their nectars. In America, these same blossoms are more likely to be dipped in batter and fried as thin fritters or stuffed with fancy mixtures of soft cheeses, chives, and paprika. However, Mexican and American chefs use only male flowers, as the females are left to fruit. I’ve given you my own recipe for stuffed squash blossoms in appendix 2. The flowers of true daylilies (Hemerocallis) are an important ingredient in some Chinese soups and are known as golden needles. They can also be steamed or sautéed as buds or flowers. When the largest buds are dropped into chicken broth and allowed to poach quickly, they taste a bit like a melding of onions and asparagus.

A current trend in American cooking is the use of the aforementioned flower confetti. Petals and whole flowers of pansies, nasturtiums, Johnny-jump-ups, and chive blooms are tossed with a range of greens to add color and flavor to salads. Fresh flowers of borage are more likely to be served with sliced cucumbers or frozen inside ice cubes.

On the dessert cart at a trendy restaurant, you may find flowers in lavender ice cream or floral shortbreads and various pastries. Sometimes they are sprinkled as edible confetti across sweet desserts. Flowers can be candied to produce elegant creations as edible garnish or dessert toppings. Pansies, Johnny-jump-ups, and borage flowers are excellent choices for candied flowers, made with vodka, egg whites, and powdered sugar.

Candied European sweet violets (Viola odorata) were once popular treats in German-style candy shops in the United States, especially in Brooklyn, New York. Today, in Vienna, they are still used to flavor and decorate desserts with white frosting based on meringues and whipped cream. These delicate sugared flowers look almost too pretty to eat. Colorful edible flowers can be diced or added whole to your favorite ice creams, fruit sorbets, or gelati. Various edible flowers can be added whole or minced to honeys to make flower honey, flower syrup, or floral jellies, floral sugar, or flower candies.

Flowers find their way into cold beverages and can be especially refreshing, such as hibiscus, rose, or chrysanthemum petals in iced tea, lemonades, or other iced beverages. Many edible blooms and petals are just as good flavor enhancers or accents in your favorite alcoholic drinks.

Although cooks or aspiring chefs have dozens or hundreds of edible flowers to select from, I’ve taken the guesswork out of choosing by summarizing the top choices of notable flower chefs, and my own, below. This annotated list has just about everyone’s top ten favorite edible flowers. Please join in the fun by making the foods you eat, and their colorful presentations works of art on the canvas of a broad plate or serving dish. Let them eat marigolds!

1. Calendula or pot marigold (Calendula officinalis), daisy family (Asteraceae). Has a slightly bitter flavor and was historically used as one of several substitutes for true saffron. Can be used in rice dishes, potatoes, or cakes. Use with caution as large quantities may affect women’s menstrual cycles, and the flower should not be consumed by pregnant or nursing women.

2. Chives (Allium schoenoprasum), lily family (Liliaceae). Have an onionlike flavor, but are not overpowering. Can be used in gazpacho, potatoes, salads, and many other savory dishes. We are talking about purple chive flowers, not their familiar green stems. The flowering stalks are usually not for sale in supermarkets, but they are easy to start from seed and flower annually even when they are grown in large pots.

3. Daylily (Hemerocallis spp.), grass-tree family (Xanthorrhoeaceae). Daylily flowers or buds yield a sweet floral or vegetal “green” flavor and are much favored in Chinese cuisine (see above under “Cooking with Flowers”). Dried, these flowers are used in sweet and sour Chinese hot soups. They can be used in pancakes, flower butter, and shrimp, chicken, and pork dishes. Be careful if you eat daylily tubers, since they can cause diuretic or laxative reactions in some people.

4. Mint (Mentha spp.), mint family (Lamiaceae). Has the minty-fresh flavor everyone is familiar with. The various mints include apple mint, orange mint, peppermint, and spearmint. Used in tabbouleh, mint sauces, garnishing drinks, in cakes and ice creams. Mint flowers are delicate additions to your cooking. Since you won’t find these along with familiar mint leaves in stores, you may have to grow your own for the table.

5. Nasturtium (Tropaeolum majus), nasturtium family (Tropaeolaceae). Nasturtium petals impart a spicy-peppery flavor to dishes. The curious round leaves are also edible. They can also be used in flower vinegars and vinaigrette salad dressings, as well as sauces such as beurre blanc. Experiment with them in Italian cooking along with tomatoes, cheese, and pastas. The gorgeous bright orange, scarlet, or yellow petals make fantastic garnishes to many foods.

6. Pansy (hybrids of Viola tricolor and the horned violet V. cornuta), violet family (Violaceae). The name of this favorite garden bloom comes from the French word pensée, meaning “thought” or “thinking of you.” The countenance-like blooms are thought to represent someone’s face in deep contemplation. Experiment with these facelike flowers in your kitchen. They are perfect tasty additions in pasta or potato salads, and dark syrups. An imaginative chef in St. Louis (Barry Marcus) has used large, dark pansy varieties to look up at diners from inside large, rounded ravioli! They are a perfect adornment that add zesty colors and interest to many dishes.

7. Rose (Rosa spp.), rose family (Rosaceae). Rose petals, with their engaging, sweet scent, make exquisite sauces. Rose petals can also be added to julienned vegetables and used in salads and vinaigrettes. Don’t forget them in desserts, as colorful, fragrant, and tasty additions to sherbet. Roses, and their loose petals, make wonderful sprinkled trousseau additions to meals as garnishes and on-table decorations. Some believe that the tastiest roses to use are species including the Japanese rose (Rosa rugosa), Damask rose (Rosa x damascena), or apothecary rose (Rosa gallica). The hybrid known as the cabbage rose (Rosa x centifolia) is grown extensively in Eastern Europe to make rose water and rose-petal jam.

8. Sage (Salvia officinalis), mint family (Lamiaceae). For centuries sages have been thought to have powerful curative and healing properties. It is not surprising that they have found their way into the cuisines of diverse cultures. Try mixing sage flowers into soups, salads, and savory dishes, including those with mushrooms and fish. Again, these are the delicate sage flowers, not the familiar and easily obtained leaves of the same plant. The stems of some varieties are bitter, so it may be best to pick off the flowers first.

9. Signet marigold (Tagetes signata), daisy family (Asteraceae). This true marigold, native to New Mexico through Mexico to Argentina, has the best flavor of any marigolds, like a spicy version of tarragon. Marigolds can be harmful if eaten in large amounts; please exercise caution by eating them only occasionally and in moderation. Marigold petals are wonderful in marigold butter, deviled eggs, and in potato salad. Try them also with quiches, pastas, and sweet desserts including fruit muffins.

10. Squash blossoms (Cucurbita pepo var.), squash and gourd family (Cucurbitaceae). These colorful yellow-orange blossoms add a delicious floral and vegetal flavor to other ingredients. This is an excellent culling method for preventing too many large tough zucchini in your home garden. Simply pick off and cook the female zucchini or squash blossoms (look for the pickle-shaped ovary at the base of the blossoms) for the table. Squash blossoms go great with peppers and corn, Mexican masa-flour tamales, or Italian pasta dishes.

Other edible blooms should not be missed, with the cautionary advice to make positive identifications and to know without doubt that they haven’t been sprayed or otherwise tainted with chemicals. These favorites include the lovely, delicate blue and white blooms of borage (Borago officinalis), although some diners complain of the prickly hairs on the flowers. In addition, some books suggest that overeating these flowers may cause liver ailments. In season, there are always Asian chrysanthemums (Chrysanthemum x morifolium, or Dendranthema grandiflorum); dandelions (Taraxacum officinale) from a nonsprayed lawn; red hibiscus (Hibiscus rosa-sinensis); the essence of a night-fragrance garden, night-blooming jasmine flowers (Jasminum sambac); the petite, smiling faces of Johnny-jump-up; the tiny, blue flowers of garden rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis); and sweet violets.

Choice edible blooms also include anise hyssop, basil, bee balm, and chamomile. Try the flowers of carnations, dill and fennel, elderberry, honeysuckle, lavender (it’s not just for soaps and potpourri bundles), marjoram, mustard, sweet orange, garden pea, pineapple guava (with amazingly delicious sweet petals), pineapple sage, red clover (watch out for lawn-care chemical treatments), scented geranium, sunflower, thyme, and tuberous begonia. Some people suggest eating the white petals of yucca flowers of the Southwestern states. However, from tropical Mexico south through Central America, people grow giant yucca (Yucca elephantipes). It is used as a living fence, but when it buds and blooms, the flowers are pickled in vinegar to be served on stuffed, grilled tortillas known as panchitas or papusas. Probably the best, and easiest, way to safely sample edible flowers is to try prepackaged assortments of edible blooms from your favorite market.

We can’t talk about eating flowers fresh out of your garden without mentioning some important caveats, the do’s and don’ts of eating the daisies. Certain blooms can sicken or outright poison you or invoke pollen or food allergies in sensitive individuals. While some flowers can be eaten in their entirety, others need to be dissected, carefully prepared for the table, to be at their best. The most toxic flowers include anemones, buttercups, calla lily, clematis, daffodils (including jonquils), delphiniums, four-o’clocks, hyacinths, hydrangeas, irises, lantanas, lily of the valley, lobelias, the true marsh marigolds, milkweeds, morning glories, nightshades, oleanders, periwinkles, privets, all rhododendrons (including azaleas), spring adonis, spurges, trumpet flowers (Solandra), and wisterias. Even sweet peas (Lathyrus) cannot be trusted. Their “sweetness” refers to their floral scent, not to their often-nasty cellular components.

This is far from a complete list of poisonous flowers to be avoided. Before eating any flower not mentioned in the top ten edible favorites, you should refer to the excellent books by authors Cathy Barash and Rosalind Creasy for a complete list of edible flowers, and how to prepare them. As with any “wild-crafting” (mushroom hunting or foraging for wild greens, berries, other fruits and seeds) you need to educate yourself before you go off, wicker basket in hand, to the woods or the familiar and seemingly safe confines of your own flower or vegetable gardens. The most important rule of all is—if you can’t positively identify a flower to genus and species, never eat it. It is important to learn and use the proper scientific names of the plants, and their flowers, you intend to eat. Also, remember that the toxicity of a plant may change as it ages. Plant molecules are just like medicines. Their physiological effects on human beings vary widely with the health, age, weight, and gender of the consumer.

Research the flowers you are considering for the table with authoritative books on the subject, not just a few minutes spent web-surfing. The genus and species (for example—the signet marigold, Tagetes signata) will distinguish this edible species from look-alike bitter species, or in rare cases confusion with truly poisonous blossoms. Use genus and species names to look up reliable information on the plant in question. This is the reason scientists always use scientific names. Most Greek and Latin words are unfamiliar to many people; but they are universally understood, a lingua franca among scientists, naturalists, and gardeners. Learn to speak their language. Avoid common names because they are too variable and totally unreliable for proper plant identifications.

Soak flowers for five or ten minutes in a bowl of cold or iced water. Shake and dunk the blossoms in the water. This will dislodge any soil particles or insects hiding within. Drain your flowers in a colander or in a salad spinner to remove the excess water. Separate flowers from their stems. A few flowers that can be eaten in their entirety include clover, Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica), Johnny-jump-ups, runner beans (Phaseolus coccineus), and violets. For most flowers, you should use only the flower petals. For roses, it is important to remove the whitish petal bases, since they are usually bitter tasting. This is also true for the flowers of chrysanthemums, carnations, English daisies (Bellis perennis), and marigolds.

If not used immediately, edible flowers can be preserved for the table by drying (using a commercial food dehydrator), by candying (see “Candied Blooms” above), or by adding to vinegars. Syrups are prepared by quickly and gently boiling whole flowers in water and refined sugar. The solution can be filtered through a common kitchen strainer, and the cooked blossoms are then discarded. Popular books on edible flowers, including the two already mentioned, have instructions and recipes for preserving and preparing flowers for the table in many interesting and delicious ways.

1. Eat a flower only when you have positively identified it to species and know its scientific name and confirm that it is not poisonous. Don’t be fooled by garden look-alikes or similar common names for different plants.

2. Do not consume flowers purchased from florists, garden shops, or supermarkets when they are sold as whole plants. You do not know the history of these blooms, and they may contain internal insecticides (systemics) or might be coated with dangerous chemicals.

3. Do not eat blossoms from plants growing along roadsides. They often contain heavy metals, such as lead, and other pollutants absorbed from automobile and diesel-truck exhaust.

4. Simply because you are served flowers in a restaurant, any restaurant, doesn’t guarantee their edibility. Ask your restaurant server, or the chef, if you are in doubt about eating any flowers placed on your serving plate or table. Don’t risk an upset stomach or worse.

Flowers and flower petals make it into some of the world’s most beloved hot beverages and tonics. Hidden inside tea bags, or as floating fragments, flowers are in plenty of hot water these days. Herbal teas commonly include whole flowers or petals as their essential ingredients. A longtime favorite in England and America is chamomile tea, an herbal tea made from the tough but fragrant blooms of chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla). This tea is favored by those who relish its calming or sleep-inducing effects. You should be careful not to overindulge, as chamomile in large doses can produce uterine contractions and miscarriages. Chamomile is far more potent as a flavoring in Manzanilla. This after-dinner cordial tastes a bit like apples (manzanilla means “little apple” in Spanish) and is mentioned in the first act of the opera Carmen. Also, if you are allergic to ragweed you should avoid chamomile, due to cross-reactivity. The lovely red or pink petals of hibiscus (Hibiscus spp.) are ingredients in Red Zinger from Celestial Seasonings teas, as well as in the herbal teas of other purveyors. Other popular hot drinks derived from flowers include jasmine, rose-petal, and lavender teas.

Green, black, and white teas from China, India, and Japan started out as handpicked new shoots of the tea bush (Camellia sinensis). Therefore, the tea in a tea bag is leaf-derived, not floral. However, the Chinese are fond of teas that appear to “bloom” in hot water. They are bundles of dried tea leaves surrounding dried flowers. When infused, the bundle “flowers” expand like an opening blossom. Dried flowers used in these tea bundles include chrysanthemum, globe amaranth, jasmine, daylily, hibiscus, and fragrant olive (Osmanthus). Flowering teas are especially common in the Yunnan Province of China. At least thirty-six kinds of flowers are used in them.

Ounce for ounce as costly as pure gold, the crimson, dried threads of saffron crocus (Crocus sativus) from Southwest Asia have been prized throughout history as a seasoning, dye, fragrance, and medicine. Saffron, as a spice, was domesticated and first cultivated in Crete, at least thirty-five hundred years ago. In antiquity, saffron probably originated from the wildflower Crocus cartwrightianus. The true saffron crocus has a large, mauve-colored flower and long, exaggerated pistil “arms,” but produces only a few fertile pollen grains. The little bulb reproduces by generating baby bulbs, so the saffron crop is uniform wherever it is grown. A restored Minoan fresco (dating from 1600 to 1500 BC, or perhaps older) in a ruin on the Aegean island of Santorini shows two young girls and possibly a trained monkey gathering the crimson pistils in a field of saffron crocuses, under the watchful eye of a seated mother goddess. These frescoes may have depicted the collection and use of saffron largely as a therapeutic drug and as a yellow dye.

In a well-known Hellenic legend about saffron, the handsome mortal Crocus falls in love with the beautiful nymph Smilax. His amorous advances are rebuffed by Smilax, and the Olympian gods transformed Crocus into the saffron plant. To this day, the saffron crocus, especially its radiant red-orange pistil arms, are symbols of an undying idyllic but unrequited love.

Botany explains why saffron is among history’s costliest and most treasured substances. Each saffron flower makes only three pistil branches, and that is the sole source of the spice and the dye. The individual flower rarely lives longer than a day. The pistils make up only a tiny fraction of the entire flower, and they lose most of their weight upon drying.

As in ancient times, the pistils are picked individually between thumb and forefinger in backbreaking stooped labor. Usually, only one to five blooms open daily on each plant. The production of just one ounce of saffron requires the harvesting of 14,000 styles from 4,667 flowers. A pound of dried saffron requires a staggering 74,666 flowers. Most of the world’s saffron is produced in Iran, India, Spain, and Greece.

The aroma and flavor of saffron are like nothing else. Saffron has an acrid taste, with a somewhat haylike fragrance, and underlying metallic notes. The love of the saffron flavor in cooking spans millennia, and several continents. In modern foods, chefs and home cooks use saffron, albeit sparingly because of its cost, in their favorite recipes. Whether powdered or as the familiar threads, saffron is used to color and flavor risotto and other rice dishes. It is an essential spice to create flavorful bouillabaisse or Spanish paella dishes.

Stuck into the rounded surface of delicious baked holiday hams are other flowers that have been used as a spice through the ages. This spice comes from the unopened, dried flower buds of a tropical tree (Syzygium aromaticum) in the myrtle family (Myrtaceae). Native to Indonesia’s Maluku Islands, clove is a familiar household spice throughout the world, lending its unique flavoring to meats, marinades, curries, and some desserts. It is especially popular in the cuisines of Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. Cloves flavor the smoke of local cigarettes (kretek) popular in Indonesia and Malaysia.

Floral nectar is either the primary or secondary reason that animals visit flowers. Photons in sunlight strike the tightly stacked grana within chloroplasts, the green microscopic units inside the leaves of plants. Through a complex photosynthetic biochemistry, sugars are made from carbon dioxide in the air, and water in the leaves, when light strikes chlorophyll molecules. A portion of these sweet sugars are moved from the leaves into a flower’s nectaries, often in crevices hidden at the bases of flowers, between the petals. The sugars manufactured are usually the “big three,” the double molecules of sucrose (one part glucose and one of fructose), and the single molecules of glucose and fructose. These molecules are transferred to nectar glands from leaves via special interconnecting tubes known as the phloem.

Bees and other pollinating insects seek out the sweet nectar from flowers. Mostly, it is used as a metabolic intermediary to power their flapping wings, carrying them aloft. Bees drink the nectar, sucking and lapping, then carry it home to their nests within honey stomachs. Back at the nest, the bees stand motionless while regurgitating the dilute nectar onto their tongues (proboscides). As it is spit out and reswallowed, back and forth hundreds of times, the nectar is gradually concentrated into honey as the excess water is driven off. (I never claimed honey-making was pretty.) Honey bees also add an enzyme, invertase, that breaks down compound sugars into simpler ones and prevents your jar of honey from turning into a crystalline mass. The honey is finished and ready for the bees to store in their honeycombs when it reaches 80 percent sugar and 20 percent water. In wildflowers and garden blooms, nectar concentrates are usually 20–50 percent dissolved sugars.

Honey comes from various races of the Western honey bee, including the Italian race, which are the dominant bees kept by US and European beekeepers. Having evolved in the Asian tropics but spreading into the temperate regions of Africa, Europe, and Asia, the eleven species of true honey bees (Apis) have become hoarders, stockpiling the sweet stuff as insurance against long, cold winters. Colonies need to store and use several hundred pounds of honey in capped combs, the bees’ pantry, in areas such as the northeastern United States, regions with intense winters.

Solitary, ground, and twig-nesting native bees consume nectar for themselves, as flight fuel, but also mix nectar with pollen to feed their grublike larvae. Only honey bees and the stingless bees (Melipona and its relatives; the meliponines), all of tropical origins, store honey in double-sided honeycombs, or grapelike, waxen storage pots in the case of Melipona and allied genera. In the mountainous regions of North America and Asia (especially China), the charismatic black-and-yellow-striped, fuzzy bees known as bumble bees (Bombus spp.) also store honey in their underground nests. These social bees make grape-size, waxen honey pots. However, unless you are a hungry skunk or other small animal, the few teaspoons of honey you might get by digging up a bumble bee nest would not be worth the stings.

Beekeepers extract honey from the combs of Western honey bees kept in Langstroth hives with their handy removable frames. Hot electric knives slice through the wax cappings, and the frames are placed upright side by side in a metal centrifuge. Spun at high speeds, the viscous, amber-colored honey is thrown out of the wax cells, hitting the side walls of the centrifuge and trickling down into a reservoir below. Raw or organic honey is not processed further, except sometimes by filtering it through cheesecloth prior to bottling. Most commercial honeys sold in supermarkets have been pasteurized. After being heated to 161 degrees Fahrenheit for a time, the honey is pumped hot through a filter using diatomaceous earth before being bottled. For a real treat, try raw floral honeys, which are much tastier than the heated and/or blended honeys most people are used to eating.

For the best that honey has to offer, look for small wooden boxes or plastic rounds that hold natural comb honey. Beekeepers placed these inside hives and the bees filled them up. This is the most natural, unprocessed, and flavorful honey you can experience. Comb or chunk honey is great as a gift to family and friends, ones who don’t know the pleasure of this culinary delight, straight from the flowers to the bees to us.

Inside flowers, in the thin tissues that secrete nectar, much is happening. These aren’t simple sugar factories. Trace amounts of rarer sugars other than the big three (sucrose, fructose, glucose), along with amino acids, proteins, glycosides, and phenolic compounds, are added. Some of these nonsugar molecules give nectars, and subsequently the honeys made from them, their characteristic tastes and other properties. Some bitter honeys fluoresce yellow, green, or blue under an ultraviolet light, such as almond honey. The bitter phenolic chemicals are a flower’s way of keeping ants from stealing all the sweet stuff without pollinating. Crawling on flowers and buds, ants are usually nectar robbers and not efficient pollinators, unlike bees and other hairy-bodied insects.

Floral nectar is not honey water, and honey made by bees is not sugar syrup. If you want a cheap, flavorless sweetener, buy cane or beet sugar. For the best experience, that of the honey-loving connoisseur, don’t settle for anything less than real honey, especially unprocessed or comb chunk honey. We love honeys not only for their sweetness, but their delicate and unique flavors and aromas. Like wine or beer, no two honeys are alike. This is because the nectaries secrete a unique blend of sugars and other flavor components. Most important for its flavor, nectar pools inside a blossom, resting against the flower’s diaphanous petals, waiting for a pollinator ship to dock, absorbing their delicate floral scents. This is why each honey has a unique flavor, its terroir.

Walking down a supermarket aisle, you will likely find a half dozen different kinds of honey. Most of these come from the largest commercial honey producers, the big trade-organization collectives such as Sioux Honey Association (SueBee honey), which began in 1921. Consumers seem to prefer light-colored honeys, like those from clover blossoms, instead of the darker amber ones that many beekeepers such as myself prefer. Clover honey is a standard, dependable, if somewhat bland example. Sure, it has the characteristic honey flavor, but for me it lacks any special or delectable floral character. You might also find “wildflower” honey at your market, which could be a mix of nectars from almost any of wildflowers from different regions. The United States has few regulations for identifying and labeling the floral sources of honeys. Caveat emptor! Still, you can reliably find flavorful gems such as orange-blossom or tupelo honey (from tupelo or black-gum trees, the genus Nyssa). Tupelo is an especially favored honey because it doesn’t crystallize and harden in the jar during storage.

For a bit of fun, go to a specialty shop, or online, and sample some unifloral honeys. These are honeys made from only one type of nectar. Organize a honey-tasting party for your family and friends. See if they like the deep rich brown and molasses-like flavor of wild buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum) honey, or the greenish honeydew honey (bees collect exudates from feeding aphids or scale insects) from fir trees in the Black Forest of Germany. Or try some of my favorites from down under, including Tasmanian leatherwood (Eucryphia lucida; sublime!) or pōhutukawa (Metrosideros excelsa) honey.

If you are traveling to the southern Mexican states of Yucatán or Quintana Roo (including the cities of Mérida, Cancún, or Chetumal) in the Yucatán Peninsula, be alert for what might just be the best-tasting and most flavorful honey in the world. Several honey bee–size native bees from the low, tropical forests of this region collect floral nectars from canopy trees and distill them into runny, but exquisite-tasting honey. My favorite comes from the sacred or “lady bee” (xunan cab in the Mayan language; scientifically, Melipona beecheii) bees, which have been kept in log hives (jobones) by Mayan beekeepers and farmers of this region for three millennia. Visitors to the popular archaeological sites of Cobá and Tulum can see representations of the Mayan bee or descending god (Ah Mucen Cab) holding grapelike wax and resin clusters, the honey pots.

You may have the best luck finding genuine stingless-bee honey in Mérida, or driving into the Mundo Mayan lands, and Mayan cities such as Felipe Carrillo Puerto, about a two hours’ drive north of Chetumal, near the Belize border. Since each bee colony produces but one or two quarts of golden honey each year, prices are high, and beware of counterfeits (you may be buying honey from Africanized honey bees). Unfortunately, for now, you will have to travel there in person to try this fabulous bee ambrosia, since federal agricultural regulations forbid its importation into the United States.

Another gift from the world’s flowers that you may not have thought about is pollen. The oily dust staining your fingers after touching the large, orange anthers of an Easter lily are its pollen grains. They are a superlative food for bees and a few other pollinating animals. The grains contain all of the protein, essential amino acids, lipids, minerals, vitamins, and the sugars that bees need to rear their young from egg to adulthood. Pollen is like beefsteak or soybeans are to us, while floral nectar and honey are the energy-rich sugars that these insect fliers need to power their foraging trips in search of more flowers.

Fresh pollen differs in nutritional content according to the flower’s mode of pollination. Flowers pollinated by bees are rich in amino acid and oil. Unfortunately, it’s hard for humans to collect enough pollen in daisies or petunias to have enough for a meal. Yes, you can put a wire-mesh pollen trap behind a hive’s entrance and knock pollen pellets off bee legs, but you might also be eating a few bee hairs and bee lice. This is the natural pollen product sold in health-food stores.

Wind-pollinated flowers release clouds of pollen often containing starch granules, but who wants to climb a tree or knock grains out of thousands of grass heads? One plant does provide lots of pollen, for a few days in spring, that’s easy to harvest providing you don’t mind wet feet. Cattails (Typha) are found in temperate, freshwater sites all over the world. While some North American tribes may have harvested cattail pollen, the Maori of New Zealand are the ones known as pollen-pastry cooks. As late as the 1880s they were still collecting pungapunga (cattail) pollen by the bucket, mixing it with water, and baking it into cakes. The botanist William Colenso (1811–99) ate some and found its taste reminiscent of gingerbread.

While you can easily buy honey bee–collected pollen pellets online, or from your local health-food store, pollen is an expensive and, to my thinking, far from ideal human food. People simply aren’t bees; we didn’t evolve guts with enzymes for handling and digesting tough pollen grains. Since honey bees often collect pollen from wind-pollinated allergenic plants including grasses, eating pollen can be risky if you are a pollen-sensitive individual. If you suffer from hay fever, after your most recent encounter with the airborne pollen ragweed, mulberry, or olive trees, you may think of it as a scourge rather than as a gift. But you would be wrong because the cereal grains—domesticated grasses including wheat, barley, oats, millet, rice, and corn—keep the world’s 7.2 billion people from starvation. The other 35 percent of our global agricultural diet comes from animal-pollinated fruits and vegetables.

We’ve traced around the world the casual and fine art of eating certain flowers, how they flavor our meals, add spice and excitement to our palates, and create divinely scented flower waters (rose and orange waters), honeys, and sweet condiments. Now, it is time to boldly go into purely aromatic delights, to understand why roses and other flowers delight our noses, and to understand the secrets of perfumery.