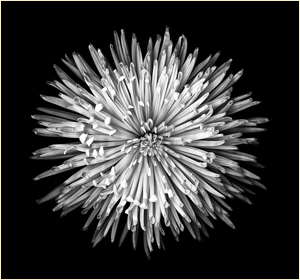

Streamerlike petals in a mum (Chrysanthemum sp.)

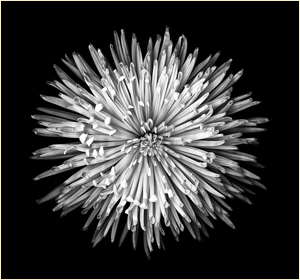

Streamerlike petals in a mum (Chrysanthemum sp.)

Almost everyone appreciates the myriad forms and inherent beauty of flowers. We don’t know who in ancient times first depicted flowers before historical written records or art was made that survived to the present. Cave paintings along with incised petroglyphs created by many cultures do not generally include recognizable depictions of flowers. In rock art around the world, we usually find geometric shapes, along with the fierce, large game animals that provided food, hides, sinews, and bone tools for these hunter-gatherers. These animal-inspired cave paintings are some of the first and finest artistic expressions demonstrating our ancestral appreciation of the natural world. Widespread symbolic depictions of flowers by artists came much later.

For the oldest depictions of flowers, we return to the ancient Egyptian culture and its stone monuments along the Nile, where garden scenes appear in numerous frescoes and stone bas-reliefs in homes and temples as early as 2600 BC. Water-lily flowers are often portrayed, with people enjoying the sweet scent of their blooms, as in the often-reproduced image Nakht and His Wife Taui Admiring a Blue Water Lily.

Flowers played important roles in myths and legends of the Greeks and the Minoans. Flowers were important components of the fabled mosaic-tile murals created by Minoans in Crete and much later by the Romans, such as those found in the homes and gardens buried in the coastal cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum. A few Minoan murals have survived. The beautiful Springtime Fresco of Akrotiri (1500 BC) from the Aegean island of Santorini reveals the Minoan fascination with flowers native to their archipelago.

From 550 to 800, as the Roman Empire collapsed, floral art images began to vanish from Europe. Early Christians looked upon flowers, and floral art, with suspicion. They viewed flowers as symbols of the dead and dying, and also of nearby decadent pagan cultures, and had little to do with them. But at the time Charlemagne was crowned Holy Roman Emperor in 800, he had seen flowers in Muslim gardens during the Crusades in Moorish Spain, and it was a time for a resurgence in floral arts.

In Far Eastern Asia, traditional Chinese gardens date to the Han Dynasty nearly two thousand years ago. Chinese gardening was closely allied to Chinese landscape paintings on mulberry paper, of which many surviving examples can be found in museums and private collections. These paintings often portray flowering plants, including bamboo, fruit trees including loquats, lotus blooms and leaves, and also conifers such as pines. They are sometimes known as bird-and-flower paintings. Landscape painting was regarded as the highest form of Chinese painting and generally still is by most scholars. Japanese artists also had an early start, depicting the flowers (e.g., lotus, azaleas, cherry blossoms) of early shinden-zukuri gardens, from at least the Heian period from 785 to 1184.

Flowers were drawn and recopied frequently in the books of plant-based medicines we know as herbals. Flowers were also used as symbols by Christians. For example, Christ’s wounds on the cross were symbolized by the five petals of a wild rose, and passionflowers (Passiflora spp.) had similar religious symbolism. Flowers were lavishly illuminated and brilliantly colored in the borders of the pages of medieval manuscripts, regardless of topic. They also appear in early paintings as wildflowers among the rocks, as in the Adoration in the Forest by Fra' Filippo Lippi from 1459.

After the invention of vision-extending instruments, scientific tools such as the telescope and microscope, people could and did look at the world of nature, including flowers, in minute detail, and in different ways than ever before. Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) described, sketched, and painted numerous Italian wildflowers, especially those near the hamlet of Anchiano, in the small town of Vinci. The German painter Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) painted flowers with meticulous care, including his Violets (1503). These were essentially floral portraits, as if the flowers he painted were people. Mainly, the depiction of flowers in Renaissance high art contained both sacred and profane pictorial messages. Thus, the Archangel Gabriel offers a white lily to the Blessed Virgin Mary, symbolizing her purity. We also find huge paintings derived from earlier stories in Roman myths showing Venus surrounded by flowers and her various immortal and human lovers.

The Dutch East India Company held a two-hundred-year monopoly in the spice trade that made Holland a rich country, especially from the 1600s to 1700s. The spice and sugar trades gave the country’s new ruling class of bankers and merchants unprecedented but often temporary wealth. Much of this money enabled private sponsorships of the visual arts, literature, and science, often including collections of seashells, posed taxidermic animals, exotic insects, and other natural-history curios and unusual artifacts. These nouveaux riches remained in touch with everyday life, and the commissioning and buying of paintings was extremely important to them.

During the seventeenth century in the Netherlands, flowers were the next big thing, a mania and passion resonating across all levels of Dutch society. The great Dutch bulb industry began in the early 1600s with importation of species, flower mutants, and hybrids from the Ottoman Empire. As these unusual large flowers were acquired and admired, their representation in flower paintings achieved unprecedented popularity in Holland. Earlier artists sponsored by the Roman Catholic Church now found themselves without Church patronage as the Reformation kicked up its heels and the Calvinist Church took hold in Holland. Enterprising freelance artists got to work, studying and painting flowers of all types, but especially the new darlings of the garden, tulips, crown imperials, red ranunculus, Mediterranean narcissi, and peonies.

The Dutch took the painting of flowers to an almost clinical level; their floral depictions are virtually photo-realistic. Most of the flowers in Dutch paintings of this period had religious symbolism—lilies for purity, and sunflowers interpreted as conforming to God’s world. Floral still lifes were especially popular in Antwerp, with artists including Pieter Brueghel the Elder and Younger. Most famous for his floral paintings was the influential Jan van Huysum (1682–1749), whose paintings, for example Bouquet of Flowers in an Urn and Vase with Flowers, both had a popular aesthetic appeal and also served decorative functions.

Exemplars of fine Dutch floral painters include Ambrosias Bosschaert the Elder (1573–1621), Balthasar van der Ast (1593–1657), and Jacob Vosmaer (1584–1641). Many paintings, such as Vosmaer’s elegant but dark A Vase of Flowers, combined blossoms from many countries in a single vase, in one grand flowering visual feast. For wealthy Dutch merchants, and royal art collectors such as Emperor Rudolf II in Prague, the floral oil paintings were a significant part of life and their interests. These wealthy collectors also owned showy flower gardens containing rare plants that often cost more than commissioning original floral art.

Amazingly, tulips, omnipresent today, were then prohibitively costly. Hiring a famous Dutch artist of the period to paint a floral still life was less expensive than owning even a single tulip grown in a pot. A flower painting would everlastingly capture the beauty and essence of an unobtainable possession, a prized rare living flower. The dates of these paintings convey the eras in which certain ornamental species from Asia and North America entered northern-European horticulture. A painting of a vase attributed to Gillis van Coninxloo II (1544–1607) overflows with marigolds from Mexico, while a second painting by Hendrick de Fromantiou (1633–94) has another Mexican marigold, but that flower is joined by a tropical passionflower (Passiflora foetida).

The best still lifes were exacting portrayals yet mere illusions of real flowers. Look carefully at a selection of Dutch floral still-life paintings. I imagine that any modern florist (or artist) would be envious of these immense and spectacular floral arrangements. They seem to defy gravity. It’s doubtful if a single additional flowering stem could be crammed anywhere into their vases. Not only that, but does the choice of the flowers by the Dutch artists seem a bit strange to you? They should. Yes, some paintings stick to themes in specific seasons, such as the flowers of early spring or autumn. The majority of Dutch paintings from this period, though, mix species from many lands and from all seasons. They bloom together although they were painted in an era without greenhouses or overnight florist delivery services. Take, for example, the lovely arrangement by Jan Davidsz. de Heem (1606–84) in which a floral arrangement competes with tempting platters of fruit. The ripe cherries and currants of summer share their table with the English daisy (Bellis perennis), hybrid primrose, and pansy of spring.

In A Bouquet of Flowers in a Crystal Vase (1662), an oil on canvas by Nicolaes van Veerendael (1640–91), a shiny glass vase is jammed to overflowing with intricately rendered blossoms (fancy tulips, peonies, carnations, iris, a marigold, hibiscus, and others). Typically, the still lifes are arranged with harmonious colors, in a convincing illusion of three-dimensionality, with flowers centrally placed and symmetrical. The background of this painting, along with most Dutch still lifes, is extremely dark, almost black, forcing the viewer’s attention to the front and center, focusing on the exuberantly displayed flowers. A sulfur butterfly rests daintily on a peony in the lower left-hand corner of the Veerendael composition. Several small insects are usually included in the paintings of this genre: ants, caterpillars, or beetles crawling over the greenery, or on the supporting table. Fanciful, colorful butterflies flit, or sometimes a fat bumble bee flies in the air around these Flemish bouquets.

One of the most powerful depictions of a flower from any period of history is the engaging Self-Portrait with Sunflower by Flemish baroque artist Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641). This painting exuberantly shows the artist in an elegant reddish silk shirt pointing to a magnificent sunflower. The sunflower (Helianthus annuus), loved both for its massive flowering head (with up to two thousand individual florets) and edible seeds, is North American in origin and was originally grown by New World civilizations and tribes. By the time Van Dyck immortalized a flowering stem in oil, this species had been grown in Europe for little more than a century.

The Dutch still lifes focused on good and pleasant things, flowers and foods, that are ephemeral. Their message is one of unique but transient beauty. The flowers will soon wilt and die along with everything else depicted in these paintings.

Colorful flowers abound in Pre-Raphaelite art. Many European painters gave us detailed studies of women and flowers. They were obsessed with the subject, depicting over and over young women and flowers, especially yellow flowers. You virtually can’t find a Pre-Raphaelite canvas in which lovely young ladies, wearing fanciful medieval costumes, aren’t looking at, picking, smelling, or in various ways posing with flowers: lilies, roses, mayflower buds, forget-me-nots, yellow irises, and even foxgloves. Paintings by Élisabeth Sonrel (1874–1953) are especially delicate and intensely floral. They are photo-realistic but engaging, combining Pre-Raphaelite intensity and a French symbolist painting style. These artists, such as John Waterhouse, draped women in beautiful gowns and elegant floral garlands. In dreamy scenes, young maidens and muses look wistfully into the distance with hopeful expressions. Other notable artists of this genre include Eleanor Brickdale (Natural Magic), Emma Harrison (A Dream of Fair Women), Lizzie Siddal, Sir Frank Dicksee (The Sensitive Plant), Arthur Hughes (Ophelia), and Sir John Millais (Ophelia).

Ponder, for example, the famous Hylas and the Nymphs (1896) by John William Waterhouse (1849–1917). It’s a memorable scene from the story of Jason and the Argonauts. Hylas wants to gather water from a pool, but the nymphs find him so beautiful that they drag him under the water. As they are water nymphs, naiads, their pond supports a healthy population of white water lilies (Nymphaea). But look carefully at the yellow flowers in their hair. Those are yellow pond lilies (Nuphar), native to North America! The Victorians enjoyed yellow pond lilies in their goldfish ponds.

By the twentieth century, with the rise of Modernism, realistic still lifes had become unfashionable. Édouard Manet (1832–83), the father of Modernism, painted flowers, but used them as secondary elements in his canvases. In his Olympia (1863), a female nude is attended by her maid holding a bouquet of flowers. Late in life, Manet created simple pastel flowers (e.g., Moss Roses in a Vase, 1882). His loose and free brushstrokes bear no resemblance to the exquisitely detailed flowers in the Dutch still-life paintings.

Claude Monet (1840–1926) emerged as the leading artist in outdoor impressionism. Nearly everyone who appreciates fine art enjoys viewing his diverse impressionistic paintings, whether they are haystacks, bridges, bowlers, or flower studies and painting series. He favored garden and landscape scenes most of all, and like other impressionists of the time, he applied color in tiny dabs of pure paint, unmixed, and without using blending strokes. The flowers in Monet’s paintings are not realistic but “impressions” of color, grand painterliness, and decorative elements. In his Wild Poppies (1873), his flowers are simple, short brushstrokes instead of realistic blooms, splotches of bright red set against a green background. In 1883, Monet settled near the village of Giverny, about fifty miles from Paris. His lavish gardens allowed him to paint en plein air amid the sunshine, peony bushes, and buzzing bees. Here, he created his famous water garden with abundant water lilies, great clumps of irises, and lush flowering stems of Wisteria. In his later paintings, the flowers become less important than the abstracted masses of colors. Monet seems to have painted flowers not for their own sake, or symbolically, but as an exploration of his continued growth in art.

Interestingly, Monet suffered from blurred vision due to cataracts during most of his later career. As his visual acuity diminished, his color perceptions also shifted to yellowish hues. His palettes changed dramatically from the dreamy pastel hues of his earlier works to the much darker reds and browns, muddied tones, used in the last years of his life. Perhaps Monet’s dreamy surrealistic landscapes were the direct result of his blurred vision. Eventually, he underwent cataract surgeries in 1923, two years before his death at eighty-six. Artist Edgar Degas (1834–1917) also suffered from chronic visual problems that are reflected in his works.

In contrast, Odilon Redon (1840–1916) imposed a personalized style on the flowers in his paintings. They appear to be floating in air, as in Day, painted in 1910. In Ophelia among the Flowers (about 1905–8), they are not depicted as they flowered in nature. In this period of later Modernism, there seems to be no reference to the visible world as the paintings gradually become abstract art. Over time, floral themes were generally eliminated from these and other Modernist compositions.

American artist Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986) was also influenced by the abstract art movement. O’Keeffe’s stark linear quality, with thin, clear colors, and bold compositions, produced her signature abstract designs. However, when she wasn’t painting vast Southwestern landscapes, O’Keeffe focused on enlarged, intimate features of flowers, their folds and crevices, as well as their sexual parts. Critics and scholars of O’Keeffe talk about the cycles of life, birth, death, and decay symbolized in her work. Others interpret her vibrant flowers as sensuous symbols of overt human sexuality and actually compare them with a woman’s genitals. This aspect of her work is still debated among professional and armchair art critics. O’Keeffe herself denied the sexual interpretations of her flower paintings. Perhaps the last word should belong to O’Keeffe, who is reputed to have said, “If you don’t understand it, too bad.”

Nevertheless, by the mid-twentieth century, painting flowers had little to do with mainstream modern art. Now, flowers were simply not subjects that professional artists chose to paint.

Postmodernism is a term applied to American art of the 1960s meant to encompass the post–World War II era and has become a descriptive term for the many fluctuations and modifications in modern society and culture. This is the artistic movement that rejected everything grand, along with universal stories and paradigms of religions, philosophy, gender, and capitalism that have defined culture in the past. In this postmodern world, flowers as something worthy of artistic rendition have been rediscovered and rehabilitated.

Andy Warhol (1928–87) painted Do It Yourself Flowers in 1962. Part of the work was created using a commercial, hobbyist paint-by-numbers kit. In his work, flowers were irreverently used in kitsch, mass-produced prints. In a 1964 exhibition titled Flowers, his images were silk-screened prints of flowers with added paint. Here we see flowers stripped of all their sensuality, along with much of their realism and beauty.

Now, consider flowers by artist Janet Fish (b. 1938) from this same period. They are engaging and beautiful, painted in a more realistic style. In her Daffodils and Spring Trees (1988), daffodils are placed against a background landscape. Her flowers are skillfully painted, filled with light, vibrant colors and interesting small details. In a way, paintings by Fish parallel the earlier Dutch still lifes.

Artist Ben Schonzeit (b. 1942) also created beautiful flower paintings. His Floral with Self-Portrait (1988) is an especially representative example of his work. Here, the flowers are once again sensuous, painted with great attention to realistic detail in an almost photo-realistic style. Schonzeit created traditional still-life images of a vase with flowers on a table. He often painted them as a pastiche, with a backdrop theme of borrowed Degas or Picasso images in tones of black, white, and gray, with his bright flowers in the foreground.

Baby boomers will remember how flowers were repeatedly used as common motifs in the pop art and the peace-culture art of the 1960s. They decorated thousands of Volkswagen minibuses, all sorts of hippie buses, and posters perhaps best appreciated under black lights or under the influence of various mind-altering botanicals. Most of these images could not be identified in a standard field guide to the local flora. Despite the kitschy overuse of blossoms not found in nature, they represented a noble sentiment of the era—“make love, not war.” Indeed, this was flower power at its best and most potent.

As painters lost their interest in flowers for their own sake, they were embraced by the new art of photography. Although the pioneer photographers of the nineteenth century primarily focused their creative attention on portraiture and grand landscapes, when they did turn their lenses to fresh flowers, it was long before color film. Today, we forget about these photographic pioneers as millions of people around the world now take snapshots of their favorite blooms, then post, tweet, share and “like” them with Facebook friends millions of times every day. This photographic equalization has essentially destroyed the ability of most professional photographers to earn a living wage. Today, digital blossoms exist by the billions, ready for illegal reproduction or sharing, are highly undervalued and sold from myriad online sources.

It is uncertain who was the first photographer to capture the image of a flower. Certainly, some famous photographers have produced classic black-and-white (panchromatic film) images of flowers in nature or in the studio. Ansel Adams (1902–84) shot roses on driftwood, along with trilliums and other wildflowers when his large, eight-by-ten-inch view camera wasn’t pointed in the direction of a prominent landscape in Yosemite or the California High Sierra. The great Edward Weston (1886–1958) and Brett Weston (1911–93), no relation, also created elegant black-and-white floral images. Edward Weston enjoyed photographing the delicate petals of Magnolia blooms, along with Paphiopedilum orchids, cactus flowers, and lilies. His flowers are equally as sensuous as the curves of his erotic bell peppers, seashells, and human nudes, such as those of his model, muse, and lover, Charis Wilson. Two of Edward Weston’s photographs, a nude (1925) and a shell (1927) are among the most expensive black-and-white silver gelatin print photographs ever sold, as of 2013.

San Francisco–based artist Imogen Cunningham (1883–1976) was another powerful innovator and pioneer in still-life flower photography. Cunningham’s night-blooming cactus explodes starlike against a jet-black background, or witness her unopened magnolia bud or several magnolia flowers (especially her close-up of magnolia pistils entitled Tower of Jewels [1925]). Then there’s her version of calla lilies, the famous Two Callas (1929). In Europe, German Karl Blossfeldt (1864–1932) is widely known and appreciated for his influential book Unformen der Kunst (1928), containing exquisite close-up photographic studies of flower buds, ferns, and leaves.

The erotic quality of flower images returns again in the photographs of Robert Mapplethorpe (1946–89). With the possible exception of Brett Weston, Mapplethorpe emulated the exquisite sensuous vegetable (peppers, etc.) and flower studies of Edward Weston like no other photographer. Mapplethorpe’s flower photographs display sensuality and sexuality, emphasizing the phallic quality of some species. Calla Lily (1988), for example, captures the lush folds and surface texture of the stiff, waxy bract (a colorful modified leaf) that enfolds the phallic cob of flowers known as a spadix. Who said botany isn’t sexy?

Mapplethorpe makes comparisons and fully understood that flowers are the genitalia of flowering plants. Poppy was one of his few color flower photographs. When first exhibited, it was perceived as erotic. That Mapplethorpe’s flowers are perceived as overtly sexual is likely because, in gallery exhibitions, they were often displayed alongside his panchromatic photographs of explicit homoerotic images. Perhaps someday his flower art will be judged solely on its merits, the appraisal not biased by the cultural controversies that developed during the late 1980s, when his life was claimed by AIDS.

We also remember Flower Power, a Pulitzer Prize–winning historic photograph taken in 1967 by photographer Bernie Boston for the now defunct Washington Star newspaper. We’ve all seen this powerful photograph of a young Vietnam War protester placing carnations, by their stems, inside the barrel of the rifle of an equally young National Guardsman confronting him only a few feet away. Fortunately, the outcome was peaceful.

It isn’t possible to name, or review, all of the living photographers creating evocative floral portraits. Dominique Bollinger (b. 1950), a French photographer now living in Italy, creates exquisite black-and-white flower photographs. Those from 1996 to 2011 are extremely sensuous and soft, with tender, sweeping curls and spirals, and usually a soft focus. His photographs of lilies, roses, magnolias, fuchsias, orchids, and camellias are all cropped in a manner that evokes Weston’s style. He’s produced two books of his works, including Fleurs in 2012.

Arizona photographer Robert Rice has produced a rich body of floral photographic work. His full-color, brilliant images of irises, roses, and peonies, along with many other blooms in alluring combinations of studio lights and background reflectors, fairly glow. Rice studied under Ansel Adams in the 1970s, and many of his photographs have a similar look to that of his mentor. Like Rice, working in brilliant color, is J. Scott Peck of Berthoud, Colorado. Peck’s blooms have an exceedingly luminous quality, based on intricate studio lighting techniques. Some of his favorite subjects are irises, hibiscuses, and the popular Stargazer lily. Carol Henry has also produced large color images of various flowers. Flower photographs have been created by David Johndrow, using selective focus and digital sepia-toning of his subjects, while Tony Mendoza creates flowers shot from below outdoors, and from other interesting camera angles.

One of my favorite flower photographers shoots without a camera. Robert Creamer, of Maryland, is a scanographer not a photographer. Creamer uses the flat glass plate of a high-resolution graphical-arts flatbed Epson digital scanner as his camera and lens. The scanner performs as if it were a wide-field microscope, with high magnifications and narrow depth of field views that are impossible to achieve with even the best cameras. Creamer arranges living, dying, and completely dried blooms of roses, peonies, chrysanthemums, and other flowers on his scanner. Like Creamer, and Alfred University moth artist Joseph Scheer, I’ve been smitten by the lure of the scanners, placing my own flowers, fossils, leaves and insects upon their wide glass eyes. A few fine artists are now discovering the unique lighting and look of flatbed scans for making exquisite fine art floral prints. Flatbed optical scanners are no longer only for copying your receipts at tax time.

Because flowers have been revered and admired since antiquity, it should not be surprising that flowers are depicted on the sides of ancient and modern coins minted in bronze, silver, and gold, from several countries. Coins minted in Rhodes, the Carian Islands, show either Rhodos, the goddess of the island of Rhodes, or Helios, while on the reverse face of the coins are blossoms, usually rosebuds. Yehud silver coins (c. fourth century BC) minted in Jerusalem depicted flowers, animals, and people. Madonna-lily flowers were commonly used on these ancient coins. Silver coins from Cyrene (modern Libya) of the sixth to fifth century BC show symbolized images of silphium stalks (likely an extinct species of Ferula), fruits, and seeds. Some ancient Chinese coins were shaped like plum blossoms with five petals.

A few modern coins depict flowers, including the gold-and-silver, two-euro coin minted by Finland. This coin shows cloudberry flowers (Rubus chamaemorus) and berries designed by Raimo Heino. Austrian shilling coins often depicted edelweiss flowers. Coinage from Hong Kong has depictions of hibiscus and other blooms. The mugunghwa rose (likely the biblical rose of Sharon) is the national flower of Korea and has appeared on its ten-won coins. Stylized pomegranate flowers grace some modern Iraqi coins.

Flowers also embellish the paper currency of many countries. Jasmine flowers figure on the Indonesian thousand-rupiah note of 1959, and orchids are depicted on banknotes from Singapore. Flowers have been used to decorate banknotes from Belarus, Guinea, Romania, and many other countries. In 1967, the Australian government issued a colorful purple $5 banknote depicting the great English botanist Sir Joseph Banks (1743–1820) and the flowers he collected while part of Captain Cook’s exploration of the part of the coast of Australia now known as Botany Bay.

Colorful flowers routinely adorn the postage stamps of many countries, and these paper-and-glue artistic creations are eagerly anticipated, used by the public and collected by amateur philatelists and stamp dealers. Especially beautiful floral designs can be seen on the postage stamps of countries in diverse regions including Australia, Brazil, Egypt, Germany, Italy, New Zealand, Switzerland, the United States, and many others.

The arranging of groups of colorful flowers into garlands, collars, hair ornaments, corsages, and large formal bouquets has been a human pastime for millennia. Flowers were formed into decorative clusters and ornamentation by the Egyptian, Chinese, Japanese, Roman, Greek, and Byzantine cultures. Over four millennia ago (2500 BC) ancient Egyptians created vast numbers of floral arrangements; pharaohs commissioned literally millions of formal bouquets as temple offerings to their many deities. Giant composite bouquets, three or four feet tall, were created by florist guilds. Wall paintings showed how women of the court wore extensive flower arrangements in their hair. Floral displays were also often used as part of funerary offerings and rituals.

Flower arrangement in Japan became the most subtle of arts and is known formally as ikebana, derived from the Japanese words ikeru (“to keep alive, arrange”) and bana (“flower”). Thus, ikebana is essentially the art of giving life to flowers, or arranging flowers, stems, and leaves, especially when done in a minimalist way. Nature and the human spirit come together in this formalized Asian art. Most ikebana is based on a triangular form, usually scalene. Small twigs usually outline the triangle.

The origins of ikebana are lost to antiquity, but it may have come to Japan with Buddhism in the sixth century as part of rituals of offering flowers on an altar or to the spirits of dead family members. Certainly, ikebana dates back at least five hundred years to the time of the Shiun-ji (Purple Cloud) temple in Kyoto. An early priest of this temple was a master at skillfully arranging and displaying flowers. After that time, other Ikenobo priests became associated with the art of these floral arrangements. By the fifteenth century, ikebana was a well-defined art form with formalized instructions and rules. At least four major styles of ikebana—Rikka, Nageire, Seika, and Jiyuka—exist.

By the twentieth century, ikebana commonly took on expressions of modernism and a free style, with Moribana (standing style) and Nageire (slanting style) predominating. Often stems, leaves, and flowering stems are held upright in a shallow ceramic or wooden bowl of shallow water. Decorative rocks can be added to the arrangements. Ikebana art is shown on Japanese television and taught in schools to foster the appreciation of natural beauty.

Flower arrangements in ancient China occurred by the Han Dynasty (207 BC–AD 221). Followers of Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism all placed cut flowers (especially the peony, tiger lily, orchid, and pomegranate) on their temple altars. This veneration of flowers seeped into their paintings, carvings, and embroidered textiles. Floral paintings are seen on plates, silk fabric, scrolls, screens, and vases of these and later periods in China.

The modern trend in flower arrangements in Europe dates from about AD 1000 and is almost always associated with church ceremonies. During the Middle Ages (476–1400), monks grew extensive gardens containing a mixture of medicinal herbs and decorative flowers. We see decorative flowers in their altarpieces, illuminated manuscripts, and paintings. During the Renaissance (1400–1600), we find the burgeoning of large and impressive floral arrangements, especially set in finely crafted marble, Venetian-glass, and even bronze vases. Foliage was woven with flowers into garlands used to decorate walls, vaulted ceilings, and wall niches. Petals were placed in baskets or strewn on floors or streets, adding their color and scents.

During the early baroque period (1600–1775) floral creations were largely symmetrical and oval, with crescents and S-curves gaining widespread popularity. The Dutch and Flemish preferred well-proportioned, large bouquets. By the Napoleonic era, flower arrangements favored strongly contrasting colors placed in simple lines or triangles displayed in urns. From France to England, the Georgian period (1714–60) preferred oriental designs based on trade with Turkey and the Far East. This popularized some of the most fragrant species as the English believed that their scents cleansed the air. Elite women of Georgian England carried (or wore) floral nosegays so that people meeting them would smell (and see) something nice. Nosegays also perfumed the wearers as they made their way through a malodorous city. Later, tussie-mussies (late eighteenth and most of the nineteenth century) were minature floral arrangements worn decoratively on clothing.

By Victorian times (1837–1901), great heaps of flowers were packed tightly into vases and other containers, often in asymmetrical arrays. Popular flowers in arrangements included white Madonna lilies, blue cornflowers, and French calendulas, along with irises, jasmine, narcissi, and pinks (carnations). As the red and black spots on pansies often resemble little human faces, they enjoyed sentimental appeal with many Victorians. Most American styles of flower arrangements from our colonial period through the early-twentieth century merely copied French, English, and Italian styles.

Aside from the depiction of flowers by the ancient Egyptians, Greeks, Romans, and Minoans on works of fine art (frescoes, bas-reliefs, and mosaics), some of the earliest and finest renderings of flowers are in handwritten and illuminated (illustrated) medieval manuscripts in Europe, produced from AD 400 until the early-sixteenth century. Many illuminated manuscripts were concerned with religious themes and were often gilded with foil.

The “illumination” of these manuscripts refers to additions of decorative elements, including marginalia, tiny but intricate illustrations, and those on alphabetical letters. Fanciful geometric illustrations and plant and floral motifs were common in manuscript borders, and some had symbolic meanings. Some of the intended readers of these manuscripts were illiterate, and the flowers and their symbolism moved the story along and helped communicate the message. The types of flowers depicted in these manuscripts are the ones we might expect: lilies and roses, acanthus, anemones, and violets, but also such lesser known flowers as cranesbill (Geranium maculatum), dianthus, wallflowers, and even Cannabis.

Decorative tapestries reached their zenith in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, in Germany, Switzerland, and France, and in the seventeenth century in Flanders and Brussels. Flowers, including roses and peonies, were frequent decorative elements. One famous medieval tapestry, The Unicorn in Captivity (Netherlands, c. 1500) shows a penned unicorn surrounded by many plants and flowers, in the late-medieval tradition of using fields of millefleurs (thousands of flowers).

Floral designs and geometric flower-inspired patterns on antique rugs were almost universal elements used by carpet weavers in many cultures, but especially those in China, Egypt, India, Israel, Persia, Spain, Turkey, and Ukraine. Floral elements needn’t be diminutive or dainty decorative elements. They can be bold features that dictate the placement of neighboring elements within the rug. Some depict bouquets, while others use flowers in garlands, medallions, or exquisitely repeating and interesting patterns.

Rugs from Ukraine and the Caucasus Mountains regions used flowers woven in an abstract and stylized fashion. Rugs from pre-twentieth-century France used lush painterly blooms, with exquisite shading and hyperrealistic details. In antique rugs from China, we find lotus blossoms used symbolically, along with ornate chrysanthemum blossoms as decorative signatures used in myriad ways. In the early-twentieth century, Chinese art deco rugs, featuring floral motifs, were created by American artist Walter Nichols (1885–1960). Persian and Indian weavers were fond of transforming flowers into stylistic “Shah Abbasi palmettes” (a symmetrical palmette having two floral sprays on top), and also used rosettes and other secondary botanical features. Persian city carpets were created in naturalistic styles. These famous city carpets (e.g., Kerman rugs) were almost always woven incorporating floral motifs. Indian Agra rugs also bear rosettes against multicolored backgrounds.

One of the earliest depictions of flowers on ceramics is a tulip motif on a clay pot excavated from the Minoan ruins of Knossos on the island of Crete. Pottery finds in a cave sanctuary at Kamares on Mt. Ida in 1890 revealed a cache of remarkable fine clay pots called Kamares ware vessels. They have abundant floral designs of rosettes and spirals. Nature themes abound with marine life and highly stylized depictions of palm trees, crocuses, and lilies. Late Minoan pottery often takes on a floristic style along with abundant leaf forms and designs.

Floral motifs have been used on Chinese ceramics, especially fine porcelain, since at least the Tang Dynasty (618–907). Bowls created in the shape of upturned flower petals are also Chinese favorites. The famous blue-and-white porcelain-ware produced in China was fully developed by the fourteenth century and is often decorated with flowers. Chinese pictorial designs, including flying birds, fanciful dragons, lotuses, and rose flowers began appearing in the thirteenth century.

Colorful Ottoman ceramics were produced beginning in the second half of the fifteenth century in Turkey, near the town of Iznik. These magnificent blue, red, and green bowls, dishes, bottles, carafes, jars, and other items featuring floral motifs were used in the kitchens of the Ottoman court. Although Iznik ceramic patterns were influenced by medieval European herbals, the most common motifs were flowers from the Turkish countryside gardens: carnations, hyacinths, roses, and tulips, with the slender pointed tulips being the most prized and frequently used.

Exquisite porcelains from England often feature highly realistic and beautiful flowers. Especially fine examples of soup tureens emblazoned with tulips and other flowers are the work of William Billingsley (1758–1828) at the Derby porcelain factory from about 1792 to 1813. Existing examples of Derby porcelain can be found in the Victoria and Albert Museum. Among the sixty thousand decorative patterns found on Limoges porcelain created by Haviland & Company since the 1890s are various floral motifs, especially pale pink roses. Extremely popular and bestselling floral patterns are also found on Wedgwood bone china, produced in England. Wedgwood Kutani Crane plates have a strong Chinese influence, including blue cranes and numerous flowers. Other patterns include floral sprays on the dinner-plate rims. Wedgwood’s Charmwood pattern (1951–87) has arrays of brightly colored flowers and greenery, along with bees and colorful butterflies.

New ways to capture floral shapes and create art include scanning and printing their forms (using laser scanners and 3-D printers). By drying flowers in silica gel, then using a computed-tomography scanner, it is possible to capture the fine details of small flowers and then create bronze sculptures. As with other natural objects I have scanned, I’m now taking my flower scans and preparing the files for 3-D printing. Thus starts the long process of creating molds for lost-wax casting and finally casting in bronze. As mentioned in University of Arizona professor Alan Weisman’s 2007 book, The World without Us, bronze sculptures will last far longer than most other human art forms or buildings. My cast bronze flowers should be around for a while. In “The Flower and the Scientist,” chapter 13, we’ll learn of other uses in biological research for the life-size versions of 3-D flowers created on a 3-D printer in hard plastic.

Tucked away in Cambridge, Massachusetts, within the venerable Harvard Museum of Natural History are the world-famous Blaschka glass flowers. Nearly a quarter million visitors every year make a pilgrimage to Harvard’s redbrick Natural History Museum, but most come to gaze in disbelief at the jaw-dropping glass creations. Indeed, these artificial flowers are one of the most popular tourist attractions in the entire Boston area.

Officially known as the Ware Collection of Blaschka Glass Models of Plants, the glass flowers began as a scientific and educational art commission by Professor George Goodale (1839–1923), who was the first director of Harvard’s Botanical Museum. Goodale wanted a collection of highly accurate botanical models he could use as instructional aids in his classes, presumably during the harsh Cambridge winters when he couldn’t obtain fresh leaves, flowers, and fruits outdoors. Goodale commissioned a Czech father and son, Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka (1822–95, 1857–1939), from Hosterwitz, near Dresden, Germany. As a testament to their skill and stamina, the two shipped numerous fragile glass flower-teaching models to Goodale at Harvard for fifty years (1887 to 1936).

In all, the Blaschkas made 847 life-size flower models (of 780 species in 164 flowering-plant families) by hand in delicate glass. Additionally, they created 4,300 smaller glass models of botanical details including enlarged plant parts, cross sections of flowers, and other anatomical sections. The glass flowers also depict pollination relationships with animals. In 1997, a visiting botanist, David Schnell, was amazed to find that the glass flower of the carnivorous plant we call a butterwort (Pinguicula) also held a diminuitive glass bee. At the time, the floral biology of Pinguicula was unknown, yet here in the collection were all the unsuspected pollinatory details wrought in glass a century earlier.

In their lifetimes, the Blaschkas were rumored to have invented a secret glass-working process that had made all the magic possible. It is far more likely, however, that they were astute naturalists and talented observers in the fine German tradition and deft master artisans. Today, no other glass craftsmen have been able to master the realistic duplication of flowers in silicon dioxide. It appears that the Blaschkas took their best techniques to the grave, but today’s glass artists continue to serve both the science of flowers and botanical education in many magnificent ways.

Byzantine craftsmen developed the intricate and colorful glass we recognize today as Venetian glass, especially from glassmakers on the island of Murano. Better-known styles include millefiori glass, a style that includes many thin layers folded over and over. The word millefiori is derived from mille (“thousand”) and fiori (“flowers”).

An elephant was in the room, and I was gently fondling it. Actually, it was an oversize elephant folio, a magnificent and famous book on flowers printed in 1799. On a research trip to St. Louis’s Missouri Botanical Garden, I ventured to their botanical library. The main collection, with its two hundred thousand volumes, is one of the best scholarly resources on plants anywhere in the world. I rose from a plush leather chair in the opulent dark-oak-paneled rare-book reading room and approached the massive center table. “They must really trust me,” I thought to myself, and wondered where were the white gloves, release forms, and the strict instructions I’d been given at other antiquarian book libraries. Left alone, with no overseers, I was free to sample the botanical wisdom and beautiful floral art of the ages.

Before me was arguably the most famous work of botanical scientific illustration of all time, the unique The Temple of Flora by Englishman Robert John Thornton (1768–1837). The book is massive, twenty-two by eighteen by two inches thick, and a hefty twenty-one pounds. Few original bound and complete copies exist today. Most have been ripped apart for their thirty-five colored plates—rich eye-candy combinations of aquatint, line etching, mezzotint, line, and stippled engravings. Individual color plates can sell at auction for $8,000. A complete copy of The Temple of Flora, especially one with an interesting association (i.e., owned and signed by someone famous), might sell for as much as $250,000.

Slowly and carefully turning its yellowed pages of exquisite images, I saw the famous “Night Blooming Cereus,” set against dark woods, a clock tower in ruins, and a brooding sky, like a poster child for eighteenth-century European romanticism and paintings. My personal favorite is the bright and cheery plate simply labeled “Tulips.” Seven magnificent stems topped with flame-streaked Dutch tulips are thrust against a cloudy sky, verdant landscape, and coastline. Here is a potent visual symbol of the tulipmania that aroused passions in the Netherlands of the 1630s. Each time I’ve been in the presence of this book, it moves me to again consider the amazing roles that flowers have played throughout human history.

Robert Thornton was trained and practiced as a physician. Thornton devoted all his earnings and time pursuing botany and producing his monumental book as a tribute to Linnaeus, the father of modern taxonomy. Thornton engaged the most gifted flower artists of the day to craft the luscious oversize lithographic plates. He tried but largely failed to enlist wealthy patrons to subscribe to the edition and then absorbed the costs personally, eventually bankrupting himself and his family when sales of the Temple were much less than he anticipated.

The Temple of Flora is properly known as a florilegium, and such books were popular with the wealthy and privileged from the second half of the eighteenth century through the early-twentieth century. Meant as works of science, they are often huge folios for two overlapping reasons. First, in an age before photography, a large folio allowed viewers to see the actual size of illustrated plant. Second, the depictions often contained a second insert that magnified the individual organs within a flower. This takes us through the scientific period (from 1735 through 1860) when plants were identified primarily using Linnaeus’s method of counting and comparing the number of organs inside a flower. He was only interested in male stamens and female pistils for his plant classification system. His followers added such characteristics as the number of sepals, petals, and how seeds were attached to the ovary walls. To show such fine characters, artists illustrated the greatly enlarged floral parts.

Some florilegia were based exclusively on living-plant collections acquired by powerful people. One of the best if not the greatest among florilegia artists was the Frenchman Pierre-Joseph Redouté (1759–1840). This artist happily drew and colored the flowers owned by members of the French aristocracy, with their sponsorship. When many former patrons lost their heads to Madame La Guillotine, Redouté switched to the ever-expanding gardens of Empress Josephine.

The all-importance of the Linnaean method meant artists and scientists had to work together to describe and illustrate new species of plants. In this age before photography, botanical artists accompanied scientists on expeditions that often turned into long and dangerous voyages. These men were adept at drawing and coloring illustrations of flowers based on fast-wilting specimens or recently pressed and dried materials. The illustration of a flower often outlived its illustrator by centuries as some artists never returned from these early voyages.

Consider the loss of Sydney Parkinson (1745–71). He accompanied Sir Joseph Banks on Captain Cook’s 1768 voyage around the world through the southern hemisphere, but poor Sydney died of dysentery off the coast of Java. His great florilegium features the flowers of southern Africa, tropical Asia, and some of the first illustrations of the winter-blooming flora of Australia. They were not published until 1988.

Ferdinand Bauer (1760–1826) was revered by the scientific community of his day. The body of his work was used extensively to understand and illustrate the intimate internal anatomy of flowers and other plant organs. He was known for his florilegium of the plants of Greece, but his real fame came from his trip to Australia under Captain Matthew Flinders in the early 1800s. By the time he returned from Australia, he had amassed eleven cases of fifteen hundred illustrations of Australian plants. His depictions of eucalyptus flowers with crimson stamens and his masterful drawing of the giant Gymea lily (Doryanthes excelsa) and the scarlet banksia (Banksia coccinea) are still reproduced on posters, postcards, and calendars across Australia.

Some purists arrogantly consider “mere” botanical scientific illustration to be a craft rather than true fine art. Thankfully, these feelings are changing, and this earlier divide between “high” and “low” art is fading away. Any artist who drafts living or preserved plant specimens using graphite or ink, watercolors or other pigments, or creates engravings or scratchboard art is considered a scientific illustrator. These artists’ exacting work is more than beautiful since their photo-realistic renderings also capture scientifically accurate details. I’ve enjoyed commissioning the exquisite botanical illustrations of fellow Tucsonan, artist Paul Mirocha, for my books and scientific articles. At various times botanical illustrations have shocked and challenged our view of how we see and interpret the natural world around us. The next chapter will show that living flowers, and insights from their careful study, have changed science and also enriched our lives.