5

Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown: “American Music, Texas-Style”

Soon after World War II, a tough new style of electrified blues guitar came crackling over radio airwaves and jukebox speakers. At the forefront of the movement was Aaron “T-Bone” Walker, who’d recorded his debut 78 in December 1929 and had been Blind Lemon Jefferson’s “lead boy,” as helpers were called, earlier in the decade. Like Charlie Christian, whom he knew, T-Bone was quick to adapt to the electric guitar, which he first featured on his 1942 Capitol single “I Got a Break, Baby” / “Mean Old World.” By the end of the 1940s, Walker had recorded dozens of swinging, sophisticated records. In the process, he became, as Johnny Winter pointed out, “pretty much the father of the electric blues style. He influenced everybody.” Nowhere was Walker’s influence more pronounced than in the early recordings of Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown.

Gruff, direct, and fiercely individualistic, the Stetson-wearing, pipe-smoking Brown had a rich singing voice and spirited, horn-like approach to the electric guitar, which he played bare-fingered. Unlike T-Bone Walker, who unabashedly declared himself a bluesman, Brown took umbrage at this classification. “I’m a musician,” he once growled at me, “not some dirty lowdown bluesman. I play American and world music, Texas-style. I play a part of the past with the present and just a taste of the future.”1 While Brown was rightfully regarded throughout his long career as the greatest living exponent of the swinging, sophisticated blues school inaugurated by T-Bone Walker, he was equally adept at R&B, Cajun, bluegrass, and country.

My first encounter with Gatemouth Brown took place on June 13, 1978, when he and his wife Yvonne invited me to visit them at their temporary residence near San Jose, California. It had been a couple of years since his previous album, the small-label release Blackjack, and he’d yet to sign with another label. After speaking with me about his life and music, Gatemouth performed a few songs on his fiddle. Soon after saying goodbye, I pulled off to the side of the road and jotted down my initial impressions: “Closing his eyes and drawing a bow across the strings, Gatemouth Brown could fiddle you a Louisiana lullaby so sweet it would melt your deepest cares into dreams of a mystical, fading Cajun twilight. Or he could strap on an electric guitar and play the clean, polished lines once blown through the sweaty trumpet of a 1940s Swing Street jazzer. A veritable Renaissance man of American music, Gatemouth can claim the names bluesman, Cajun fiddler, country picker, and jazz man—they all fit, but none of them begin to encompass the man or his music.”2 These words, it turns out, would hold true for the rest of his career.

You started recording in 1947, right?

Yeah, 1947, right.

With Maxwell Davis?

Yeah, that was the first band that I ever recorded behind, Maxwell Davis. Yeah.

How has the blues changed over the years since then?

Well, in this way, I would say: the blues took a toll in a very disastrous way, simply because the good blues people was made ashamed to play it. You might say the new breed come out, and good blues was considered. . . . What they did, they took from the backward blues and linked it with the good blues and made the guys that could play good blues ashamed to play it because they called it the wrong kind of names. Being honest about it, they called it “nigger music.” That’s how people used to come up and refer to it as, and the artists resented that, most of them, and they went into something else to try and shield themselves from that category of music.

Who do you think were the best practitioners of good blues at that time?

Well, I would say T-Bone Walker was one. They had people like Tampa Red, people like that. As far back as I can remember, Tampa Red, when I was a small kid, used to be a blues artist. And then when I first heard of a lot of blues, T-Bone Walker was doin’ it, you see.

When you first start listening to blues music, was it from Louisiana or Texas?

No, I’m a Texan. I listened to all kinds of music for a long time, then I decided to go and invent a style of my own. And I did so.

How old were you when you made the decision?

Oh, about twenty-two.

Had you been playing by then?

Yeah. Not long, professionally. I had been playing since I was five years old.

Tell me about that.

The kind of music that I played when I was five years old wasn’t blues. It wasn’t jazz. It was country, Cajun, and bluegrass. That’s what my father played, see? He played fiddle, guitar, banjo, mandolin—all those instruments. But not professionally, because my dad was an engineer for the Southern Pacific Railroad in Orange, Texas. Of course, that’s where I grew up. He would only play on Saturday nights for house parties, that sort of stuff.

How did you start playing?

I started strumming guitar behind him at the age of five. The guitar was bigger than I was. When I got to be the age of ten I started on the fiddle.

What kind of songs were you playing behind your dad?

Tunes like “Boil Them Cabbage Down.” Let me see, what else? Oh, I heard one the other night on a tape some people from the Ozarks sent up to me, some nice bluegrass music. I’ve got some stuff that I’m gonna redo up, a tune like “Bully of the Town” and all them real heavy mountain music. Of course, that music mean more to me than any other music, because I’m more familiar with it. And jazz and blues just came automatically.

Do you remember any of the advice your dad gave you?

Yes! He said if I was gonna play any music at all, the first thing I must learn is to tune my instrument. [Laughs.] And I did that first, before I could play very well. And the second thing, say, “Don’t overplay. Play what you can, but play it well.” And I’ve tried that. And the next thing he told me, “Don’t get stuck in no one bag.” Said, “Learn to play some of everything, and that give you a widespread repertoire.”

When did you first start playing in public?

Well, when I was about sixteen, around Orange, Texas. A little old band there. Our leader was a guy called Howard Spencer. He was a mailman by day and musician by night. He played the alto saxophone. And the funniest thing, I didn’t know any different. Take, for instance, a tune like “C Jam Boogie.” Now, I’m telling you what key it’s in. He would always play it in B-flat. Start us in B-flat. In fact, everything he ever played was in B-flat. It was funny. After I grew up and learned about music, it was real funny how them guys used to do. Oh, he was a card.

What kind of band was it?

It was a little swing band. A little swing band.

Did it have a name?

Yeah. They called it the Gay Swingsters at that time. I didn’t name it! I didn’t like that name. I didn’t name it. You know, that’s what they called it. It was funny.

What were you playing in this band?

Now, you gonna flip over this—I was the drummer! That’s right. And I furthered my career—after I grew up, I was a drummer with a twenty-three-piece orchestra in San Antonio. Hort Hudge, he was Caucasian, had a twenty-three-piece orchestra at that time. He gave me a chance to be a drummer. And they called me “The Singing Drummer” because I would do vocals and drum at the same time.

So how long did you play with the Gay Swingsters?

Oh, like, five, six years, I guess. I can’t remember. I never did make no money. I never will forget this. These guys used to take us, like, to Beaumont, a place called Chain’s nightclub, upstairs, and we played hard all night and get three nickels apiece. And the guy who was handling the thing took all the money. That’s what you consider paying dues!

Where did you go from that band?

Well, from that band, I joined an old road band called W. M. Bimbo and the Brownskin Models, out of Indianapolis, Indiana. It was an old road show. I’m not even eighteen yet. I’m about sixteen, seventeen—something like that. Went all the way up to Norfolk, Virginia. He took all the money and the bus and stranded everybody—all the kids, the youngsters—and went back to Indianapolis. I was the only one who was able to get everybody out of there. I got a job in a club they called the Eldorado Club on Church Street in Norfolk, Virginia. I never been away from home that far in my life. I was playing drums with this little band, whatever band—I don’t even know who they were. But the guy owned the club was named John Ireton. And that’s the biggest money I ever made in my life [until then]—gave me $125 a week to sing and play drums with the band. And I sent all these other kids home, one by one, every weekend, until 1941. When the war broke out, my mother sent me a letter, said I had a questionnaire, so I caught a train and went home. I went in the service and stayed five months, ten days, and a few hours. Got out and went to San Antone [San Antonio], Texas, and got my first break with Hort Hudge’s band at the old Keyhole on the corner of Highway and Pine. Don Abbott used to be a big band leader, owned the club at the time. And I worked there two years and for very little money—say, fifty dollars a week.

What were you playing?

Drums. And so Don Robey from Houston, one of the big club owners and tycoons in the theatrical business, was a friend of Don Abbott’s. So he heard me and he asked me to come to Houston. T-Bone Walker was the hot stuff throughout Texas on guitar at that time, and nobody knew I play the guitar. So I hitchhiked from San Antone to Houston and went in this club and was sittin’ downside the bandstand. T-Bone Walker, he was sick with the ulcer or something. He laid his guitar down and ran to the dressing room that was about, oh, thirty steps from the bandstand. The bandstand was real long—he had six hundred people in there. The Bronze Peacock. And so just out of nowhere, I got up from there, walked up on the stage. I picked up his guitar and invented a boogie right there on the stage and made $600 in fifteen minutes in tips. All-Negro audience.

Were you playing by yourself?

No. A band was playing behind me. And the band was called—oh, what was this fellow’s name? Skippy Brook was the piano player—later on he was in my band, my big orchestra, for a long time. Oh, my gracious, I can’t even think of this guy’s name. Anyway, I started this tune, and it happened to be my first recording, “Gatemouth Boogie.” And some of the words, they, “My name is Gatemouth Brown / I just got in your town. If you don’t like my style / I will not hang around.” And it was coming to me just out of the clear blue. I was making rounds. And the women and the men and everything was just throwing money down my bosom and everywhere. And I made $600 in that period of time. So all of a sudden T-Bone Walker recovered and come down and snatched his guitar away from me, on the stage, in public. Kind of hurt my feelings. And told me as long as I live, never touch this instrument again. So I said, “Alright.” By that time, Don Robey heard all the commotion and the people screaming right up on the stage. He come down there, told me to come to his office. The next day he bought me a $700 Gibson L-5, bunch of uniforms, and I been goin’ ever since.

Was that your first decent electric guitar?

Yeah. And I recorded for that company for seventeen years.

Was that Aladdin Records?

No, that was Peacock. I started with him, and how Aladdin got in, he knew nothing about recording. But he tied me up on a contract. He flew me—the first time I ever been on an airplane—he flew me to Hollywood, California, to Eddie Mesner. And they recorded my first four sides. 1947. He [Robey] was a very smart man. After he learned about the business, he snatched me away from Eddie, and we formed the Peacock Recording Company. And that was our company for seventeen years. Mm-hmm.

Did you keep playing at the Bronze Peacock?

Oh, yes. Oh, yes.

How did your relationship with T-Bone Walker develop?

Well, it never did really develop too good. He always had a sore spot about me because, you see, I’m the one invented swing guitar—what I call “Texas swing.”

How did that come about?

I had a little country oriented into the blues. That’s what I did. I mean Caucasian country music, because that was my trend anyway. And so that changed a whole trend, and thousands of guitar players followed me after then or gave me credit for it. Like Johnny “Guitar” Watson. I notice in your magazine, many times when these guys be interviewed, they always use my name. Yeah.

How did you wrap up the 1940s?

Well, in the ’40s I decided to get me a big band. Kept a twenty-three-piece orchestra for a long time.

What did you call it?

Just Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown and His Orchestra. I had a good band. I had some fine musicians, like Al Grey, who’s now with Count Basie. Johnny Board, Nathan Woodard, the trumpet player. He went to school at the Boston Conservatory of Music. Fred Ford was a tremendous baritone player, and Bill Harvey out of Memphis, Tennessee. He was my first tenor. I had Pluma Davis on first trombone. Paul Monday was my pianist. I just had a good orchestra.

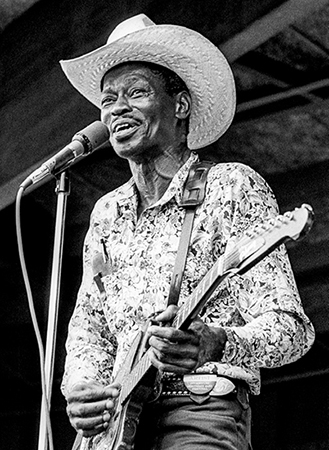

Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown plays the Monterey Jazz Festival, September 17, 1977. (Jon Sievert)

Who did the arrangements?

Well, I head arranged most of my stuff. I arranged a lot of my music. Then some of the guys in the band wrote up a lot of it for me.

How long did you stay with the band?

I kept the band about twelve years.

Did you go on the road quite a bit?

I stayed on it. And then when I saw that rock and roll was becoming a fad thing, like everybody else I had to get rid of a big band. It was a sad moment, but I had to do so. And I broke down to small groups. I saw in the future it would be hard for big bands to come back. And so I used a small group for a long time. And after that I decided to back off of recording in America, and I did—back in the late ’60s. So I freelanced around awhile and wasn’t nothing happening. Because people at that time, they wanted different music. These old doo-wop bunch was out there doing acrobats and this old hard rock and roll. I couldn’t stand the music, so what I did, I just went to playing small clubs ’round Nevada and Colorado and Texas. I had a trio and that sort of stuff, and I did that for a while. I got tired of clubs, because I really don’t like clubs too much. So what I didn’t know was that the French that was over in Europe had been looking for me for seven years and couldn’t find me. They didn’t know where I was. But they finally located me, and I started going to Europe and started recording albums. This was around the middle ’70s. I been goin’ ever since. I got about ten albums in Europe now. I always look forward to going overseas someplace.

When you had your twenty-three-piece orchestra, what kind of crowds were you playing for?

Auditoriums. Four, five, and six thousand, eight thousand, ten thousand, twelve thousand, depending on the size of the place. It was fine days, man.

Were you playing alongside other bands?

Yeah, we would have what they call “cavalcade.” See, this promoter I had was very smart. He would have what they call “The Battle of Guitars,” “The Battle of Bands.” He’d put my band up against many people. He did that against Duke Ellington, and caused a lot of hard feelings a lot of the time. I guess show biz is show biz.

Were you playing mainly guitar?

Yeah. Guitar.

When you transitioned into the rock-and-roll period, what kind of a lineup did you have?

Well, I didn’t actually get into rock and roll. I kind of refused getting into it. Because, to me, it’s not the kind of music that’s tasteful. It’s either loud or off. I never could stand that irritating music. I never could. And it has ruined a lot of musicians in more ways than one. But everybody do what they want to do, but me, I just won’t do it.

So what kind of music did you go off into?

I started easing back into what I always love—country, Cajun, bluegrass. See, because the clubs I was working was all Caucasian clubs, and that’s what I started getting back to. I got to where I just didn’t want to play rhythm and blues.

I read a quote where you said that you’ve been places where if the blues were played right, there would be fights.

Yes.

Tell me about that.

Alright. There is a type of blues, like anything else. . . . Alright, let’s go back. What cause people to get in a turmoil? Excitement—too much excitement of one thing. Now, you can get on one of these backward blues like, “Oh, my daddy had bad luck in Mississippi and my mama don’t have no food”—I’m just using that. If you use that long enough and keep pushing that one point to an audience, the next thing you know, someone, perhaps, in that audience witnessed this type of life. And when they do, they get really uptight. And maybe somebody in there they don’t like, and that’s where it’s on. I’ve seen it. Take, for instance, like T-Bone Walker. I’ve seen him play blues and cause many fights. But if you play different styles of music throughout the night, you won’t have that trouble. People don’t have time to work up no emotions. You work up emotions, but it’s all a happy medium, you see. That’s why I mix up all of my music. If you notice, my record is all mixed up—Cajun, country, bluegrass, jazz, blues, and ballads—everything. And the next thing, you don’t play one tune too long. That will get it. I found that out. I’ve watched people play, man—at least some blues artists now—what they consider “Chicago blues.” Well, there’s no such thing as Chicago blues. It’s blues brought from Mississippi into Chicago. They’re ashamed to use the word “Mississippi,” so they use “Chicago” to label that music up in Chicago. That’s what I tell people—there’s no such thing as Chicago blues.

Do you agree with the observation that Mississippi blues and Texas blues are different?

Sure, it’s different. If you notice the lyrics, Texas blues don’t have the heartbreaking hardship lyrics like in Mississippi. You have to listen to both sides to see the difference. And even the phrases are different, tonality. Everything is different.

How influenced were you by the early Texas blues people such as Blind Lemon Jefferson?

I wasn’t.

You just weren’t exposed to it, or you didn’t . . .

Well, I heard it, but I just didn’t like that caliber of music. My blues is based on orchestration. I was influenced by people like Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Lionel Hampton, Ray Brown, Woody Herman, Hoagy Carmichael. You know, by listening. I’ve always liked the style of music of the big band. I don’t like just a real primitive-type blues. I have nothing against nobody doing it. I could play it easy, very easy, because there’s actually nothing to play. It’s just a couple of chord changes and that’s it.

As a songwriter and arranger, how do you work up orchestrated blues?

Well, in the first place, your tonality with your instruments is way different because you can name any one of these hardcore blues singers, put him with a big orchestra, and you’ll see that it don’t fit. It don’t fit. Because their changes are not like the orchestra.

Take the Kings. If you put an orchestra behind B. B. or Albert . . .

No, it will not work. It’s terrible.

It doesn’t have the same emotion?

No. You got to be able to phrase. See, actually what I’m trying to say [is] I don’t play guitar like guitar. I play my guitar like a horn.

Charlie Christian style?

No. Different from that. I play horn parts—actually, tenor parts. I can play trumpet parts, make it sound the way trumpet would sound, or a tenor.

Do you read music?

No.

How do you learn the trumpet parts?

I know how a trumpet’s supposed to sound. I know how a tenor is supposed to sound. That’s why I say I can head-arrange a whole entire orchestra. It’s just something I can do. Just a gift I can do. If you ever heard any of my records, then you can understand it. And I was taught a lot by some of the guys that was in my big orchestra. See, I was the only guitar player. And I was the first guitar player that ever led a big band in America. The first.

How has your guitar style evolved?

Since I started? Well, it went a long way—I can tell you that! It was my determination that every year it would be something new. I would never sit down in the grass and allow my feet to be stagnant. I can’t be stagnant.

How would you make the change?

Well, in the first place, you got to think music in order to play it. If one don’t think of new things to do that would fit . . . see, music is like a puzzle. If you put one puzzle together and never put another one together, you don’t know anything about another. So what you do while you’re playing music, if you got any brains at all, you must be learning more. If you don’t, you should quit. That’s what’s the trouble with most of us—we’ll get on one thing. If you notice, a lot of records out there, these guys, if they can do one thing, they wear this one thing out. In fact, you can see it, you hear it, in every tune.

How do you avoid that?

In the first place, I cannot stand to hear the same sound coming back at me. So therefore I got new things going all the time. But I can go back and play the same thing. Whatever’s on my album, I can play it. Yeah. I got a bank up here [points to forehead] that hangs in on that stuff, I guess.

Do you ever hear other musicians and force yourself to learn how they did it?

No. That’s the next thing. I will not copy off of no man. No! That’s a bad thing to do. I’ve seen people spend half of their life trying to do what somebody else do. I don’t care about doing what nobody else do. I always tell people in all my interviews around the world: Do something you can do best without copying what someone else has done. Because when you copy what someone else has done, all you’re doing is helping them. You’re not helping yourself.

When do your new developments come to you?

Twenty-four hours a day.

With instrument in hand, or without?

Without, with—it makes no difference.

Can you play anything you can hear in your head?

If I want to, yes.

Do you still play the Gibson L-5?

No. Today I’m playing one of the finest guitars—I consider—in the world. I don’t know exactly the date of it, but it was built in the ’60s. It’s a Gibson Firebird. I love this guitar.

Anything distinguishing about it?

Well, yes. It’s me. It thinks like I do and everything. In Durango several years ago a leather craftsman made me a leather pickguard for it, wrote my name on it, and it’s a beautiful guitar. I was offered $1,500 for it, and I refused.

Have you made any other changes to it?

No.

What kind of strings do you use?

Oh, I use just strings—no strings in particular. I used Black Diamonds for years, but they got to where they would break too easy. Then I went to Gibsons, and I use balled ones or whatever.

What gauge?

All different gauges—it makes no difference. I like a medium string. I don’t like too soft a string, because I like certain tones.

Do you ever use a pick on guitar?

No, I never used a pick in my life. I use my hand. I can’t use no pick.

How many fingers do you use?

I might use four, I might use two, I might use one. I might use all five.

For playing a rhythm part, what do you use?

I play overtone rhythm with my thumb and I use this finger [indicates middle finger] a lot of time for picking.

What kind of equipment are you using with the band?

For myself? Well, I like my Gibson guitar crossed with a Twin Reverb Fender amp. That give you the best sound in the world.

Do you use any effects?

No. The only thing I ever use, I put just a taste of reverb on my amp, because I like that tone, and I use a phase shifter, but with just a slow motion to it. And it gives such a beautiful quality to my instrument. On my album, you can hear it very little. I mean, just enough to give that beautiful tone.

Do you remember the make of the phase shifter?

MXR—the yellow box. Mm-hmm. It’s very, very beautiful, and a good phase shifter.

Have you been predominately an electric guitarist?

When I was a kid coming up I had an old flat-top guitar. I don’t know what it was. And I had one with this big old metal thing in it [most likely a National resophonic]—it weighed six ton. Just one thing or another. My first fiddle I tried to make out of a cigar box and screen wire, and it didn’t work out. First set of drums I played I got a big whuppin’ behind it, because I sneaked one of my mom’s washtubs out and got me two tree limbs and took my time and trimmed them down. I was in the backyard, wailing away, and my mama come out there and tore this tub all to pieces. Of course, she tore me up too. That was my first encounter with a set of drums.

In your current five-man band, how do you determine which instrument takes what part? And what spot do you leave for yourself?

Oh, well, I usually open. I play my solo. I always play a couple of courses [choruses]. I don’t play too many courses—I don’t like that. Every man plays a couple of courses when it’s time, depending on the speed of the tune. Now, fast jazz—a couple of courses apiece. I make take three, that’s about it. But it’s going so fast, it’s not long. And like that, the music don’t bore you.

So you alternate between rhythm and lead.

Yeah. See, when my guitar player is playing, then what I do, I play block chords behind him. I do the same thing behind the pedal steel.

So you’re more with the bass at that point.

Yeah. The bass, the drummer, and myself and one of the pedal steels working together, with block chords. And it sound like a full orchestra, like a complete full orchestra. I can take five pieces and make it sound like ten, whereas I’ve seen a lot of people take ten pieces and sound like five.

What’s the . . .

Secret in that? Well, use heavy chord changes. Not loud, but deep chord changes.

For an example . . .

Alright. Take, for instance, if you’re playing a tune, instead of everybody playing way up on the neck, which sounds shrill, real shrill, don’t do that. One person back off and play deep notes. He be in the same key, but he’ll be an octave [below]. That’s right. And so that fills in a spot and give the body. Just like some bass players nowadays don’t even sound like bass players. They sound like lead guitar, and that’s sickening, man. A bass weren’t meant for that, because you’ve got no bass. And some drummer, instead of using his bass drum, he’s all cymbals. And that takes away from the body of the music. So I don’t have that.

You aim for a strong foundation.

Right! That’s it. And I get it. I can take a trio, and you think it’s five pieces.

That would highlight the solo work more too.

That’s right.

How strictly do you structure your lead work?

Very strict. Very strict. You must be accurate, on time, and out of it.

Some bands will jam on for ten minutes.

I don’t do that. I don’t do that. Three, five minutes is the most. That’s when you feeling real good. That’s long enough for any tune, man.

Is there music aside from your own that you like to listen to?

Yes! I like to listen to some good classical. I like to listen to some good country, good Cajun, good bluegrass. I love it. I do not like free jazz. I do not like rock. I do not like soul what they playing today. I don’t. One-chord change. I’ve seen these bass players get on one note, man, and they hang on that note from the beginning of the tune to the very end. Well, that’s what the young people are playing. There’s nothing to it, man. It’s not music. But I’m fighting real hard to try to give them a taste of good music. And many other people are doing the same thing.

In the whole panorama of American music, where do you see yourself?

Well, it would take time, but I see myself as a teacher of quality. I do. It take some time for that, because you know as well as I know our youngsters have been brainwashed into filth and they think it’s music.

Filth?

Yeah, filth. Punk rock and all that sort of stuff is no good. But you see, that’s what you call fad stuff. It runs out fast as it get in, just like a sieve. If you notice, all these fad bands, every three months—ninety days—they have to come up with new idea in order to pick up for this loss. But good music don’t have to do that. What’s music all about? Something you can understand and use your imagination. That’s music. Music is really imagination. If you don’t have no imagination about it, it’s no good. That’s why I said all this punk rock and free jazz—how can you go sit through some free jazz? These guys all hopped up and play a tune an hour and ten minutes—one tune. How can you have any imagination?

How would you answer critics who say that rock-and-roll and punk music are a natural evolution of the blues?

No, that’s far from being the truth. Far from being the truth. Now, in the first place, how can rock and roll or how can this other stuff have any close, close relation to blues when it don’t have none of the phrases of the blues? Maybe every now and then they might accidentally slip up on one.

A lot of people have tried to figure out in a scholarly fashion where the blues is from.

Well, it’s not that hard to figure out! The blues, the real blues, came from hardship, from slavery. And it came from spirituals. Blues is a takeoff from spirituals. People being forced to work against their will, and they had a little chant to keep their sanity. And that’s how blues come about. Because if you are forced to do something, you constantly got the blues.

Where do your blues come from?

My blues come from me, because I wasn’t ever forced to do anything.

What advice would you give someone who wanted to become a full-time musician?

Don’t do what I do—do what you can best, and do it right. These things you have to watch out and not do: Don’t get into narcotics. Don’t get into alcohol. Leave them women alone and do your work. Get as much rest as you can. And when you’re not playing music, go anywhere or do anything and don’t look at no music.

What do you do to get away from it?

When we’re home, my wife and I, we love to plant. We plant flowers, shrubs and things. Do all our own private landscaping around the house. That’s right. What other hobbies I have? Fixin’ things. I love to cook—anything.

Any practical advice about how to play?

Yes. Number one. Don’t relate on being on an ego trip. Don’t relate on being loud. Make sure every note that you do is understood. Make your music so that people can relate to it. That’s it.

How often do you practice?

Very seldom. I practice in my head. I’m practicing all the time, but in my head. That’s right. And it comes out in my fingers. When I’m home, if I stay home two months, I never pick up my guitar. I lock it up and leave it. Never pick up the fiddle—unless the wife and I sit down and decide do something, she and I. But as far as, like, going and jamming with somebody—I don’t do that, man. That bores me. It’s boresome. Because in the first place, half the people you jamming with can’t play. In the second place, they play them too long. Very seldom I might jam, very seldom. And when I do get on the stage with somebody that can play, I play the same regular way like I do anyway.

What do you want to do with your music in the future?

I want it to be remembered. I want it to be remembered. You see, once you put it on record, you don’t lose it. Them tunes will be remembered for thousands of years. Three hundred years from now, you’ll play my music—and I’ll be long gone—and that will touch on many, many, many souls. I don’t care where the music goes, that will be there. That stuff will always last.

CODA: Soon after this interview, Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown recorded a new album, Makin’ Music, with Roy Clark. He then produced three fine albums for Rounder, winning a Grammy Award for Best Traditional Blues Album for 1981’s Alright Again! After a pair of albums for Alligator Records, he capped his recording career with five albums for Verve/Gitanes. In 2005, Brown’s home in Slidell, Louisiana, was destroyed by Hurricane Katrina. Deeply shaken, he moved back to his boyhood town of Orange, Texas, where he died on September 10, 2005.