7

Ricky Nelson: Remembering Rockabilly

The arrival of rock and roll in the mid-1950s brought a seismic shift in American culture. When a guitar-clutching Elvis Presley shook his hips on national television, and when Chuck Berry’s “Maybellene” and Carl Perkins’s “Blue Suede Shoes” came blaring through radio speakers, American youth embraced the music as theirs and theirs alone. Unlike the immaculate, uptight pop that came before, early rock and roll was fast, hard, visceral, even dangerous. Critics panned it, parents forbade it, preachers burned records. But kids loved it. Rock and roll brought tumultuous changes to fashion, attitudes, even lifestyles. Suddenly, it seemed, playing guitar became just about the coolest thing a young person could do.

Two schools of guitar playing dominated early rock and roll. On one side was Chuck Berry, who showed on single after single how to play a guitar just like ringin’ a bell. On the other were the rockabilly cats, who blended white country music with black R&B. At the head of this class were Scotty Moore, Elvis Presley’s lead guitarist; James Burton, who played alongside Ricky Nelson; and Carl Perkins, Buddy Holly, and Eddie Cochran, who did their own soloing. Nelson didn’t have Elvis’s snarl and swagger, and at the time he didn’t compose his own songs like Perkins, Holly, and Cochran. But he was an excellent singer and decent rhythm guitarist, and he’d been blessed with movie-star good looks. And unlike his peers, he had the best promotional platform imaginable: a hit TV show.

Originally a 1940s radio show about a real-life mom, pop, and their two sons, The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet made its television debut in 1952, when Ricky was twelve. By April 1957, when he performed his first on-the-air rock-and-roll song—a cover of Fats Domino’s “I’m Walkin’”—the show had an estimated 15 million viewers. Within a month, his Verve single of “A Teenager’s Romance” / “I’m Walkin’” had reached #4 in the Billboard singles chart. After switching to the Imperial label, Nelson brought in James Burton on guitar and rapidly produced hit after hit. Kids eagerly tuned in to each new episode of Ozzie and Harriet, hoping for another rock-and-roll performance. No mere teen idol, Ricky Nelson created some of the era’s finest rockabilly and pop records.

With the British Invasion and the cancellation of the family show, Nelson hit a commercial dry spell. During the late 1960s he shed his teen-idol image and became one of the first rockers to explore country-rock. Getting booed at an October 1971 rock-and-roll revival at Madison Square Garden inspired him to compose his beloved song “Garden Party.” During the next decade, Rick Nelson, as he now called himself, recorded albums for MCA, Capitol, and Epic, and toured up to 250 days a year. When we did our interview on June 16, 1981, it seemed like I’d known him all of my life—and, in a way, I guess I had.

Who are the best guitarists you’ve worked with?

Oh, boy. You know, it’s so hard to say. I think the two best are probably James Burton, who is really an innovator in guitar playing, and Bobby Neal. But it’s so hard to generalize, because they have really different styles.

When James Burton joined your band, how well known was he?

He wasn’t well known at all, really. The first time I heard him was in the office at Imperial Records. He came up from the Louisiana Hayride with Bob Luman. Actually, Bob Luman was auditioning for Imperial. I was looking for a band at that time. I was sixteen and so was James. I heard this guitar playing at the end of the hall. I thought, “Wow, I love the way he plays.”

Your promo material mentioned that you recorded “A Teenager’s Romance” after your girlfriend said she liked Elvis.

Yeah, I did that, and the other side was “I’m Walkin’.”

Were you interested in rock and roll before then?

Yeah, very much so. I remember the first truly rock-and-roll record that I ever heard was with Carl Perkins. It was “Blue Suede Shoes.”

What other influences did you bring with you into the studio?

Well, you couldn’t help but be influenced by Elvis a little bit. My main influence was probably Carl Perkins at that time. I really idolized him. I really tried to sound like Carl Perkins. I used a standup bass—you know, a slap bass—at that time. Actually, electric basses came in about ’57.

Did Ozzie have much to do with your getting signed to Verve?

My dad? Well, he was involved, because I was just sixteen at that time. And sure, he was very much involved.

Do you remember which musicians you used for the Verve sessions?

Yeah, I remember it was people like Barney Kessel—mainly jazz players. They really didn’t understand rock and roll. There was a whole group of people that just never quite made it, like Howard Roberts and people like that. They were really great jazz players, but they never quite made it as far as playing rock and roll goes.

Do you remember how those early sessions were done?

Yeah, I sure do. We had one studio that we recorded in. It was just one room, and we’d all go down there and work out the arrangements right in the studio there. There was no title as a producer, you know. There was no such thing as a producer at that time. They were A&R men, and Jimmie Haskell was the kind of go-between for Imperial and myself, and I remember Jimmie used to hold up chord symbols and stuff because nobody could read in there at all. All of a sudden he’d bring out a big “A,” and then all of a sudden a “C,” things like that. So that was the extent of reading music.

Was there a natural echo in the room, or was the echo on those records done electronically?

It was a real chamber, upstairs.

What were the recording techniques?

It was just really straight-ahead. And what we used to do is we’d record the drums and bass really out front, on the basic track, if we were gonna lay vocals and things on it. They ended up being about four generations down, because that was when they used to overdub.

Compared to today, what was the turnaround time between the sessions and the product hitting the streets?

Oh, God, it was just so basic and straight-ahead, you know. It was a lot more healthy, I think. We’d record like, say, on a Saturday night, and the record would be out in all the stores like on Tuesday or Wednesday. That week, it would have sold a million records, you know, if I got lucky.

Did you pick the tunes yourself?

Yeah, I did, which was a real luxury.

Did you make suggestions to your guitar players, like to bring in the country influence, or did they bring it along with them?

No, they were all from the South, you know, so it was just a very automatic kind of thing. It’s a certain feel. Nowadays they call it rockabilly, I guess, for lack of a label.

Being sixteen, how clear of a vision of the final product did you have?

Very clear, because I tried to emulate Sun Records. It was when Music City was happening, and I used to buy up all of the Sun Records down there. Because I love that sound.

Did you play guitar when you were young?

Yeah, I did.

How old were you?

Let me see—I think I was probably about fourteen.

When you moved from Verve to Imperial, was Joe Maphis your guitarist for a while?

Yeah, he was. On the first album, Joe played all the leads, like “Boppin’ the Blues” and “Waitin’ in School”—all those things.

How did Joe get involved?

There was a show called Town Hall Party with, like, Tex Ritter. Merle Travis was on it, and Joe Maphis. I got to know them because I dated Lorrie Collins at that time. I used to see her. They were called the Collins Kids, and Larry Collins was sort of a protégé of Joe Maphis on Town Hall Party. I used to go down there every Saturday night and just sort of hang out there when I was about fifteen. I got to meet all the people and hear all the stories, and I really liked the way he played.

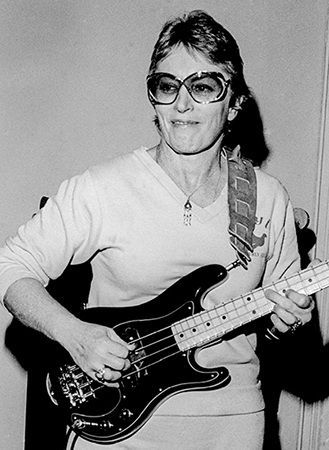

Ricky Nelson, circa 1981. (Susan Rothchild; courtesy Capitol Records)

Who were your backup singers on the early records?

It was the Jordanaires.

Was there a lot of pressure on you being compared to Elvis?

Oh, you know, at that time everybody was compared to Elvis if you stood up and played a guitar. It wasn’t really a pressure for me. It was something that I always felt was very flattering.

Being that young, did you have much artistic control over your career?

Yeah, I had complete control over it.

Did you go on many tours?

Yeah, during the summer. Actually, the first thing that I ever played was the Ohio State Fair, to 20,000 people. It’s a large step from your bathroom to 20,000 people!

Did you see the 1978 film The Buddy Holly Story?

Yeah, I did.

Was that an accurate portrayal of what it was like back then?

I just met Buddy Holly very briefly. My friends during that time were Gene Vincent and Eddie Cochran and the Everly Brothers, people like that that I used to hang out with. But I never really got to know Buddy Holly. I know they used to go out on the Dick Clark bus tours for three or four months of one-nighters. I was very fortunate at that time to be able to play buildings by myself, so I never really had to do that.

Did you do much jamming with Gene Vincent?

Oh, yeah. A lot.

Was what he played with you the same as what he played in public?

Yeah, pretty much. And we were real good friends.

Compared to today, what was the concert scene like back then?

It was really the very beginnings of rock and roll, and people were getting their clothes torn off. It was very physical.

How did you become involved with the Burnette brothers?

I met Dorsey and Johnny right around the same time I knew Eddie Cochran and Gene Vincent. They had driven out from Tennessee, from Memphis, and they pulled up in the driveway. This is after my first record. They were very persistent. They just opened the trunk, took out their guitars, and started playing. I really did like the songs and the way they sang. They had a whole bunch of what are considered to be rockabilly-type songs right now, and I really liked them. So during that time I ended up with a handful of writers that I could more or less count on for material. Guys like Baker Knight and Dorsey, and subsequently I got to know them very well.1

How much freedom did you give James Burton on your records?

Almost complete freedom, unless I heard a specific thing that I wanted him to play. You know what? I was thinking about James, and I remember before there was anything like slinky strings, he was probably the first to come up with something like that. It was when we recorded “Believe What You Say.” I remember him coming into the studio and going, “Hey, listen to this!” He’d put banjo strings on his guitar, so he could bend them way up, and that was really the front-runner of slinky strings.

What are your favorite cuts from the late ’50s and early ’60s?

Oh, boy. I’m not sure. It’s so hard to say. You’re speaking of mine? I don’t know. They all have kind of a different flavor to them—at least I tried to make them different. I think “Lonesome Town” has a special meaning to me. It was probably one of the first records with just a guitar—just an acoustic guitar and a vocal.

Over the years, have you embraced new technology as it’s come along?

It’s kind of a constant battle for me, because all the magical kinds of things that happen have nothing to do with the technology. If anything, the technology does get in the way of those kind of overtones, the generation-down type thing. Like “Hello Mary Lou” was about eight generations down. So all of a sudden we got to about the seventh or eighth generation, and the cowbell started sounding like another kind of instrument. Really. Those kind of things are very difficult to duplicate.

Do you find it easier to put together an album now?

I kind of have to always—not fight it, but just keep in mind that if the technology part of it is heard on the record, it never quite makes it for me. So in a way, it’s a little more difficult for me. Every record company wants me to have a producer, which can be easy if you get the right combination where a producer can come in with really good material and things like that. It can kind of ease the burden and let you record. But if you get a producer that wants to change your image and this and that—you know what I mean.

You self-produced the Garden Party album.

Yes.

Did you enjoy doing that?

Yeah, I really did, because when I wrote the song, I wrote it in one night. It was a very strange feeling because it was there to be written. I could hear exactly what I wanted it to sound like on a record. And then when I went into the studio, it started sounding that way. It was really exciting.

Would you recount the story of that song?

Oh, yeah. We played at Madison Square Garden. Richard Nader had been after me for about four years to do a rock-and-roll revival. I was really opposed to it. And I don’t know—he caught me at a weak moment. I had just formed the Stone Canyon Band and I was writing a lot of material. We were playing colleges and things like that. So musically it was a whole other direction that I was going in. And I just thought, “Well, okay.” I’d never played Madison Square Garden, and I started thinking of the reasons why I should do it. I never quite convinced myself, really. I’ve never been very good at faking it like that, you know. I have to make a complete commitment to whatever I’m doing in order to have it be the least bit successful. What I do, I really have to make a total commitment to it, and not talk myself into it. And that’s what happened that night—I felt really out of place being there. It was a learning experience for me. It wasn’t a sour grapes thing at all. It was just a reminder to myself that you gotta do what you believe in.

What do you view as the best period of rock and roll?

I think right now. It’s wide open. I’m playing all over, not just L.A. and New York. I’m playing all over the country, and people are really willing to accept all kinds of music. For the first time, I don’t think it necessarily has to fit into a specific slot as far as people go. Maybe the radio stations and the promotions people have to fit it into a slot to get played.

Who would have thought rock and roll would reach the proportions it has?

Oh, yeah! When I first started, people we’re saying, “Well, it’s gonna be out in three weeks anyways—it’s a fad.” Really!

And now it’s probably the classical music of the future.

Oh, sure.

What venues do you play these days?

We’ve been doing a lot of schools, a lot of concerts, and they’re really rewarding. Actually, we’ve been doing a lot of high schools.

That must be fun.

They really are, because all of a sudden we’re playing to a whole new group of people that just accept you at face value. It’s a real good feeling when they like the old songs. Like, say, “Believe What You Say,” which is a very basic three-chord, rock-and-roll song. If anything, punk rock and all that has kind of come around a complete cycle to that, and it’s a kind of a music I really understand and really enjoy playing.

Any contemporary rock and roll that you enjoy listening to?

Oh, yeah. Very much. I like Pat Benatar a lot—I think she’s great. There are so many bands, it’s really difficult. And they all have their own personalities because that’s what happens when you get bands together like that, like garage-type bands. They end up having their own sound, which is great. I think it’s a very healthy kind of thing.

What do you look for in a sideman in your own band?

It’s a very intangible kind of quality they have to have. It’s difficult to put it into words, but a certain feeling that either works or doesn’t work—especially a drummer. It’s so important to have a certain body rhythm. Like two people can play the same tempo and have it be completely different. With the band I have now, I’m really happy with it.

Who’s the guitarist in your current band?

A fellow named Bobby Neal.

How did you find him?

Well, when I was with Epic, I went down to Memphis to record an album, and he was on those sessions. I heard him play down there, and I really liked the way he played.

What kind of guitars do you own now?

I have a Martin.

Do you know the model?

Let me see—it’s a D-35. I’ve had it since I was seventeen.

Do you play lead at all?

Not really. I tried a couple of times, you know, and it took a little while to get it on tape [laughs], so I leave that up to somebody else.

Do you go on the road much now?

Oh, yeah. Really a lot. 200 days a year, on average.

How do you keep your sanity?

Well, that’s a good question! [Laughs.]

Do you play your guitar much outside of performing?

You mean at home? Oh, yeah.

Do you use it to play yourself in and out of moods?

Yes, I do. And to write. It’s weird—the best songs that I think that I have written have come from times when I haven’t been necessarily thinking about writing a song—or thinking about anything specific. It’s just maybe a mood or something like that, and something starts to happen.

Have songs ever come to you at odd times?

Not really. It’s not like I go to sleep and write a verse on a pillowcase or something. I have done that—I’ve dreamt that I’ve written this great song. I’ll write down a few words, wake up the next morning, and it’s ridiculous. [Laughs.] I guess a lot of people have done that. Usually I just feel like playing. Sometimes I’ll be walking around not necessarily thinking about anything. I know that’s how “Garden Party” started happening. When it started to happen, I wrote the whole song on one piece of paper—I didn’t want to move. I was writing on the corners, on the back, and everything.

Any advice for young performers?

All I can think about is that I really enjoy performing a lot and playing and doing what I do. That really has to be a prerequisite. It is for me, anyway. I don’t see how you can do a really good job on something where you’re just going through the motions. I just thoroughly enjoy what I’m doing.

CODA: After our interview, Rick Nelson continued to tour extensively. In 1984 he participated in a Sun Records reunion with his idol Carl Perkins, among others, which brought him his only Grammy Award. He played his final concert on December 30, 1985, concluding his encore with Buddy Holly’s “Rave On.” The following day Rick Nelson, Bobby Neal, and four others died in a plane crash. James Burton, who played with Nelson until 1968, went on to become an in-demand studio player and a mainstay in the bands of Elvis Presley and John Denver. To this day, Burton is regarded as the “Master of the Telecaster” and one of rock’s all-time greatest soloists.