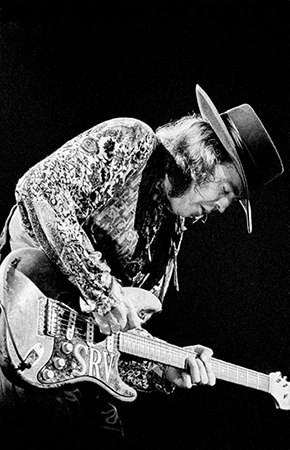

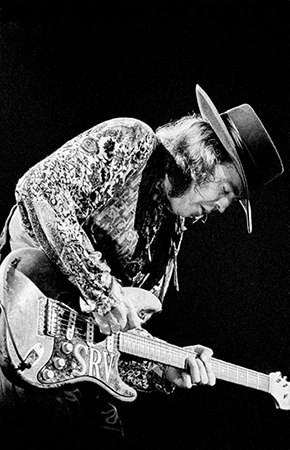

Stevie Ray Vaughan in Oakland, California, December 3, 1989. (Jay Blakesberg)

If there’s ever a bible of women in rock and roll, chapter 1, verse one should read: “In the beginning, there was Carol Kaye.” Originally a bebop guitarist, Carol crossed over into rock and roll in 1958, when Elvis Presley, Chuck Berry, Ricky Nelson, the Everly Brothers, and Connie Francis topped the charts. But unlike those who found fame and fortune as headliners, Carol chose to work her magic behind the scenes as a studio musician. A half century later, she remains a vital force in music.

During her heyday in the 1960s, Carol was a charter member of the small group of Los Angeles-based studio musicians who came to be known as the “Wrecking Crew.” At various times, this collective’s members included first-call guitarists Tommy Tedesco, Barney Kessel, Glen Campbell, and Al Casey; drummers Hal Blaine and Earl Palmer; saxophonist Steve Douglas; and electric bassists Joe Osborn and Max Bennett. Working alongside these session stalwarts, Carol played guitar and/or bass on Top-10 hits by the Beach Boys, Ray Charles, Joe Cocker, Sam Cooke, Bobby Darin, Jackie DeShannon, the Four Tops, Ike & Tina Turner, Jan & Dean, the Monkees, Paul Revere & the Raiders, the Righteous Brothers, Simon & Garfunkel, Sonny & Cher, Barbra Streisand, the Supremes, the Temptations, Stevie Wonder, Frank Zappa, and many others. In the 2008 documentary film The Wrecking Crew, Beach Boys leader Brian Wilson offered this assessment of Carol’s place in music history: “Carol played on ‘Good Vibrations’ and ‘California Girls,’ and she was, like, the star of the show. I mean, she was the greatest bass player in the world, and she was way ahead of her time.”1

Like other members of the Wrecking Crew, Carol eventually began emphasizing movie and TV dates. Her playing graced such beloved films as Airport, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, In the Heat of the Night, The Pawnbroker, and Walk, Don’t Run, to name a few. Her television credits include The Addams Family, The Brady Bunch, Hawaii Five-O, Hogan’s Heroes, M*A*S*H, Mission: Impossible, and other popular series. In 2000, Berklee College of Music named her “the most recorded bassist of all time, with 10,000 sessions spanning four decades.”2 Over the years, Carol has also written and produced some of the best-received instructional books and videos for electric bassists.

I first learned of Carol through other musicians, notably Tommy Tedesco, Barney Kessel, Howard Roberts, and Mitch Holder, who’d all worked with her in the studio and spoke of her with great regard. During our January 1983 telephone interview and later in-person meetings, I found myself captivated by Carol’s charm, energy, good humor, and get-it-done attitude.

Do you know of any women who were playing rock guitar or bass before you started playing sessions?

No, no. I knew of rock groups using women singers and all that. See, now, I was playing a lot of guitar in the late ’50s. You know, in ’56, ’57, ’58, I was playing a lot of bebop. And I was aware of rock, but to my knowledge I was the only female guitarist around in that area doing the records and all that stuff.

What town were you in?

The south part of Los Angeles. I lived there, and I worked in all the nightclubs. Most of the time, I was the only white person there, let alone being the only woman. There wasn’t any discrimination as far as I felt. There were times when I felt like I wasn’t playing up to par, and I realized it. I went home and practiced on the certain areas that I needed work on. Then all of a sudden I was very much in-demand in jam sessions, jazz work. Like, I played in Jack Sheldon’s band in back of Lenny Bruce. George Shearing asked me to go on the road with him, but I was about eight months pregnant at the time, so I couldn’t handle that, but it was a real honor.

When did you get into rock?

In the studios.

Do you remember your first session?

Yeah, very well! 1958, Bumps Blackwell came into the Beverly Caverns there where I was playing with a jazz group. I was working with Billy Higgins and Teddy Edwards. I forget who was on bass, but I used to work a lot with Scotty LaFaro, who passed on in those years. Bumps Blackwell walked in and he asked me if I wanted to do a record date. You know, Hollywood being the way it is, I said [tentatively], “Sure.” I went down there, and it was a real record date! It was a soul group featuring Sam Cooke. It was Sam’s second record that we were working on, and Lou Rawls was a singer on that date—it was his first record date too. Jesse Belvin was the other singer, and there was another older guy by the name of Alexander. It was a soul date, and it was fun. I said, “Yeah, this is kind of fun music.” It was like gospel music. So I got into it that way. Then I played for H. B. Barnum a lot—a lot of gigs and a lot of record dates. And then I started to add the guitars then.

Were you playing bass at first?

No, no—guitar.

Who’s H. B. Barnum?

H. B. is the guy who made the arrangements for Lou Rawls and for others—an arranger. He put a lot of the town to work. He wrote a lot of hit records, and he did a lot of Motown-type of dates. He didn’t work for Motown, but it was that kind of stuff. And we did a lot of hits in those years, the early ’60s.

Can you think of any?

Yeah. I played the guitar on all of Phil Spector’s dates. In fact, the guitar I used, which was my early, early jazz guitar, was an Epiphone Emperor. Most of the secret of Phil Spector’s sound was that they miked that. It was an acoustic guitar and an electric, but they miked it acoustically, and they’d dump a lot of echo on it—like on the Righteous Brothers’ “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’.” I played a lot of acoustic guitar on the Sonny & Cher stuff. The guitar fills that you heard, that was me. One of earlier hits that I played on was “Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah,” but I played electric guitar on that. That was Bob B. Soxx & the Blue Jeans. Remember that one? In other words, I played on all of Phil Spector’s hits, whether it was Ike & Tina Turner, the Righteous Brothers, or the Paris Sisters.

Did you play on “River Deep—Mountain High” by Ike and Tina?

Yeah! Uh-huh. Guitar. I’d have to listen to the record to tell you exactly which part, because he always used two or three guitars. He always used me and Barney Kessel, you know. David Cohen came in about ’63, but I started working for Phil about 1960.

What was it like working for Phil Spector? Did he have charts and definite ideas of what he wanted?

Skeleton charts, mostly, but there were some dates—especially at Sonny & Cher dates—where Harold Battiste, a sax player, wrote all those fine arrangements. They were pretty intricate arrangements, in the sense that they were different. Every hit that Sonny & Cher put out was different. The style was different, which I think really, really made them successful. But there was one of their hits where the tune just kind of lay there like a dead dog. It was a one-chord tune, and I was starting to play bass, but I wasn’t playing bass on that date. I was playing that acoustic guitar that I was telling you about. I was trying to figure out a bass line, a hook line, to make it happen. And I played a bass line, and Sonny heard it on the mike. He said, “Ooh, I love that bass line!” Now, you’ve got to realize, when I first met Sonny, he was playing tambourine on a Phil Spector date—and not very good at that! [Laughs.] I saw him meet Cher and saw all that go down. Anyway, Sonny heard that line, and he said, “Ooh, give that to the bass player.” And that’s the bass line to “The Beat Goes On.”

Really? You invented that?

Yeah, that’s my bass line. So we were called upon to read music and/or make up hook lines. See, the secret of a lot of hit records is in the bass line and the drum licks—but mostly the bass lines. Like later on, when I played bass for Quincy Jones, Quincy would get kind of backlogged with work. He had an awful lot of work, and I played on all of his films in the ’60s and the early ’70s. I played on every one of his movies, and every one of Michel Legrand’s movies, and every one of the Hank Mancini movies. To cut a long story short, Quincy would tell us to just jam. He’d bring in a rhythm section and tell us to just jam, and we’d sit there and play funk for a couple of days. You know, when you got so much work, you don’t know what’s what and you don’t care—you just want to get in, get out, and get paid. Find a parking place, and that’s it.

So anyway, I went to the movies one time, and I said, “Gee, that stuff is really familiar!” And the name of the movie was The New Centurions. And what Quincy did, which is very, very hip—and I didn’t feel plagiarized at all, I felt like, “Yeah, that’s very hip”—he wrote the horn lines on all the bass notes that I played. So it sounded like it was arranged, but it wasn’t. He took those bass fills and the bass licks that I played—because I played a lot of conga-type lines, like off-beat Latin kind of lines for funk—and he took an arrangement on top of the bass lines, so it sounded arranged. And some of the guitar hooks too—he’d take a little bit of that. I’m just saying that to tell you how important those hook lines are to arrangers, see. Like “Wichita Lineman,” they took one of my bass licks and milked that for the string part. People are not aware how important the bass is to arranging, and I’m just saying this to make them aware. Because a lot of people love to play bass, and that’s why, because you’ve got a lot of control. It’s like the basement of a house.

You were with Phil Spector until when?

Oh, all the time. All of his hits. You know, he wouldn’t do anything without me. The last time I worked for him was in ’69, and I was a little bit spaced out because my fiancé had just died. Phil was trying to make a comeback at A&M, and I was so spaced out I couldn’t play. And so he gave up—it was a flop that night.

So you were on all the famous girl-group records?

Yeah. Everything that Phil did, I’m playing on.

Mostly guitar or bass?

Mostly guitar. Bass toward the latter part of his records. Now, I started with Phil about 1960, and we did almost all the dates at Gold Star [Studios].

Were Phil Spector’s sessions different from other producers’?

They were long. It would be anywhere from twenty to thirty-five takes. He took his time. He knew what he was looking for. Like, the whole band would sit around. It seemed like Hal Blaine used to have to play drums for about an hour before he could get to the bass and then the guitar—you know, to get the balance just right. And the horn section would play chess. I saw a lot of Playboy magazines with the guys! [Laughs.]

You were the only female guitarist or bassist at these sessions?

Mm-hmm. The only one.

What were some of your other sessions like—say, with the Beach Boys or Joe Cocker?

Okay, now. The Beach Boys, I played guitar on their early records.

Like “Help Me, Rhonda”?

No, that’s bass. That’s my first bass record. “Help Me, Rhonda” was the first record I did with them on bass. I kept the strings real high in those days. I mean, the bass was a real physical instrument. I kept them real high, and I used the Fender P-Bass with the Super Reverb amp. And they always miked me. They always miked me. They never took it through the board. You know, I got a pretty good sound. Even on some of the Motown dates—like “Love Child” and “Bernadette,” I played bass on—I added more bottom, but they miked me on that stuff too. But the Beach Boys took a lot of takes too. You know, it seemed like Phil Spector kind of set the standard—it was okay to go six hours on one tune, which we did. They used all studio guys, except for Carl [Wilson]. Carl would be in the booth, on twelve-string. He mostly played twelve-string. And he’d sit and play with us, but he’d be in the booth. Lyle Rich played acoustic bass—there was an acoustic bass on there too. But you couldn’t hear the acoustic bass except like on “Good Vibrations”—for a while there’s two parts there. I played the higher part. [Sings the line.]

Did you come up with that line?

No, that’s Brian’s stuff. Now, Brian Wilson wrote all of his lines. Once in a while I played a fill or something that was mine, but I can’t lay claim to any of Brian’s bass lines. But the feel—if you listen to “Good Vibrations,” that feel is a jazz feel. It’s a walking feel [sings main bass riff]. That’s pure jazz, and Brian was greatly influenced by jazz. He was influenced by the Four Freshmen—you know, they way they sung. Barney Kessel, Howard Roberts, and I were constantly on those dates. We were constantly being amazed by Brian, because he’s the one that arranged it all, and he came up with all the ideas and everything. We met the other Beach Boys—they were really nice and all that—but it was Brian’s talent, really, that did all that stuff. On the Pet Sounds album, I played bass on all except one tune—there’s one tune on the Pet Sounds album that I didn’t play bass on. In fact, that’s George Harrison’s favorite album, the Pet Sounds album. A lot of people like that album. I mean, it’s a very creative album.

After you played on the Beach Boys’ records, would you then teach them the parts?

No. No, it’s just that they copied what we did. Like, they copied the feel and they copied the parts that we came up with, but it was Brian that wrote the parts. I mean, he didn’t physically really write them very well. He put stems on the wrong sides of the notes and like that, and we’d have to recopy it in another key and that kind of stuff. We spent time doing that too—in other words, the music wasn’t legally very good. We had to sit down and rewrite it, but it came from his head. And the parts were fairly simple, so they could go out on the road and cut them, but they couldn’t get that real, old studio feel that we got because I was in the clique that was playing on all the hit records. That’s all we did—cut a hit from 8:00 a.m. in the morning till 12:00 midnight, every day of the week. I’ll tell you some of the people I worked with: Johnny Mathis, Hank Mancini, Pet[ula] Clark, Andy Williams, Sam & Dave.

Did you play on “Soul Man”?

I don’t know the names of the records. See, I played on thousands of records, so I know some of the names of the records I played on. But I can hear stuff and say, “Oh, yeah. I played guitar on that.” I can remember the rhythmic part I played or the lead part. Remember the Alka-Seltzer ad? [Sings the familiar riff.] Well, that was me that played guitar on that. I was the lead guitar of the T-Bones—remember that group?3 That was me on that. And I played lead guitar on the Green Acres show that you’re hearing right now, and that was cut about fifteen years ago. And I played guitar on—remember the coffee commercial? [Sings the Maxwell House riff.] Okay, the very first ones were me. The electric twelve-string that you heard on the first two or three records by the Tijuana Brass, Herb Alpert’s group, that’s me. A Wrigley’s gum ad was lifted from one of his albums—that’s me on twelve-string.4 I got a lot of money for that ad. I’m just trying to give you a brief picture, because it’s really a huge thing to describe all the mountains of work that you do.

What were the hardest rock sessions you tackled?

The ones that weren’t very musically satisfying, like The Hondells, because it was so dumb, and you’d be playing that dumb stuff for hours. And I like Mike Curb—Mike Curb was a pretty nice guy. I played guitar on all those things. Howard Roberts was also on those dates, and we’d just sit there and space out. It was like, “Oh, God, I should have turned this down.” But it was a lot of money. You don’t turn down money—I mean, a lot of it, that is. That was hard. Some of the Dick Dale stuff was hard.

Did you play on stuff like his “Misirlou”?

I don’t know the names. I’d have to listen. But most of his stuff I did. Let’s see—some of the harder stuff. The stuff that took hours, and it didn’t need to take hours. Like, Phil Spector set this thing that it’s supposed to take six hours to cut a hit record, and he had such a phenomenal success that everybody thought, “Oh, I’ve got to take six hours,” and most of them didn’t have to. You know, they were practicing in the studios, just like doctors practice on their patients. They were practicing in the studio how to make a hit record, see? And that’s why it took so many hours. Now people pretty well have it down, but I’m not really thrilled with most of the music that’s coming out. It seems like the feeling is not there.

Was anyone ever surprised when you, being a woman bass player, showed up on the date?

No, no. I never got that—I guess because I had a pretty good reputation for being a live player in jazz. If you were a successful jazz player, you were very respected by all the players.

Did you consider yourself a rocker?

Yeah, yeah. I started to tell you that in my mind it was very hard to make that transition from being a very successful jazz player and an up-and-coming giant in jazz, which doesn’t pay any money, to doing studio work, which was really dumb, until I got the idea that, “Hey, it’s fun to make a hit record, and this stuff can groove too.” Even though it’s rock and roll and 8/8, it’s got its own groove to it. At that time, when I started playing on all the #1 hit records that were coming out of the West Coast, definitely then I thought, “Yes, I’m a rock guitarist.” I didn’t feel like I was a rock bassist there for a long time, because I always felt like I was a guitar player that just picked up the bass.

So your early sessions were guitar, and you switched to bass in the mid-1960s.

Yeah, ’64.

And from there it was primarily bass.

Yeah, it really shot up. I was about number-three or number-four call on guitar in those studio years, and I was making pretty good money. But then when I switched to bass, I put a lot of bass players out of work because in those years they were using acoustic bass and Danelectro 6-string bass guitar. A lot of people call the Fender bass a bass guitar, but the Danelectro is the “bass guitar,” because that’s got six strings. They’d use, like, three basses on the date. Well, as soon as I started playing bass, I put the other two bass players out of work, because I played it with the pick and it got a really good sound. And I was the only one in town that was really working my tail off.

Was it always charts and reading, or did they sometimes ask you to come with parts on your own?

Both. It was both. If I couldn’t make a Motown date, Gene Page would have a real simple bass part for the other bass player that could make it. But he would write some outrageous bass parts, and I’d sit down there and sight-read them. Quincy Jones would occasionally write some great bass parts, like the Ironside theme. And I’m also the one that played the theme of Mission: Impossible—Lalo Schifrin. So you had to be able to read all kinds of music, you know, depending upon if it was films or records. But at the same time, there’d be times you’d go on a date and there was no music written, and you’d have to skull-out a part with chords. You write them on a blank piece of paper and come up with a bass line.

Were you ever asked to join groups?

Yeah, yeah. Occasionally. See, most of the groups in the ’60s didn’t want people to know that they did not record their own music. Okay. But occasionally there’d be a call to go out on the road, but I just couldn’t afford to, because I was making so much money and I had my kids. I didn’t want to go out on the road.

Did you continue to do rock dates throughout the 1970s?

No, it became more film, but they wanted the rock-type of bass. You know, the rock-funk bass on the film thing. I have to look at some of these credits. [Carol refers to the quarterly royalty statements that studio musicians received.] Valley of the Dolls, for instance, The Thomas Crown Affair, On Any Sunday, Walk, Don’t Run, a lot of movies from Universal, which were real murder movies. Oh, remember In the Heat of the Night? I’m the fuzz bass player on that. [Laughs.]

Did you have to keep up with all of the effects?

Yes. I’m the first one who used effects in the movies—like on the theme of Airport, I used that Gibson box that had all the things like the octave doubler and that one that sounded like steam. What’s the name of that little Gibson box? Oh, the Maestro. And I’m the first one that used the fuzz tone on a bass in the movies. So yes, I did have to use the effects, but not like they’re doing now. Like, I never used a flanger or anything like that.

So in the 1970s it was mainly film.

In the film dates they still wanted the rock thing, but it was kind of like pseudo-rock. It wasn’t the real rock that we did on the Phil Spector dates or with Gary Puckett. For instance, I played on Gary Puckett’s stuff, and Harry Nilsson.

You also played with Joe Cocker and Stevie Wonder.

Yeah. “I Was Made to Love Her”—there’s a few of them I did with Stevie. A lot of that [Motown] stuff was cut on the West Coast, and people don’t know that. And then the Joe Cocker was “Feelin’ Alright.” I liked that—it was a fun record. And then Jerry Vale—a lot of pop stuff. Sam & Dave and Ike & Tina Turner—I played on their stuff a lot—and a lot of Ray Charles too, but that was like gospel-rock. That wasn’t really rock-rock.

When did you become aware of other women playing rock guitar and bass?

Well, not really until about the ’70s, when I started to see women play in rock groups live. You know, I’ve been out of the studios now—well, I do do occasional studio work—but I’ve been out in the public. Because when you’re in the studios, that’s the only life you know, and it’s like being locked up in jail or something. You don’t interact with the general public, so you don’t know what’s going on out there. You’re in there cutting all the hit records and they’re listening to you and everything, but you don’t grow any other way but in your music. See? Now, coming out, I realize the attitudes that women have to develop. But you know something? It’s really not that much different than when I got started, because I never thought of myself as a woman. I thought of myself as a guitar player. Now I’m seeing women in groups, and it seems like they’ve cut out the notion, “Well, I’ve got to play like a man.” You know, that’s not it either. You either play or you don’t play. And that’s the attitude. And the ones that seem to come across the best seem to have that attitude.

It’s like if somebody puts you down, you just gotta put the blinders on and keep going. Forget their trips—that’s their trip and that’s their hang-up. For women in rock nowadays, the ones who are successful are the ones who exploit their own talent and get it across with strength and with conviction. But the ones who are trying to put the men down or they’re trying to be cute with the boobs and that kind of stuff—you know, pretty soon they die out. But I’ve seen a lot of women players that I really like. In fact, the women that were in the group Heart [Nancy and Ann Wilson]—I like those women. They weren’t really technically fantastic players, but I like what they did onstage. And the new women’s groups coming up, I like the way that they put themselves across without being real cute and coy. In other words, they’re taking care of business without saying, “Hey, look at me! I’ve got the curves too.”

CODA: These days, Carol Kaye still plays bass, produces instructional material, gives lessons via Skype, and operates her own website at www.carol-kaye.com. In 2008, she had a starring role in the film documentary The Wrecking Crew.

Stevie Ray Vaughan in Oakland, California, December 3, 1989. (Jay Blakesberg)