9

Stevie Ray Vaughan: On Jimi Hendrix

During the pre-Internet era, few musicians had as rapid a rise to fame or as profound an impact as Jimi Hendrix. Issued in mid-1967, the Jimi Hendrix Experience’s Are You Experienced is arguably the most revolutionary debut album in rock history. The album instantly upped the ante for guitarists on both sides of the Atlantic. While others before had experimented with massive volume, feedback, distortion, whammy, wah-wah, octave doubling, and other sonic effects, Hendrix was the first to harness them all into music so extraordinarily imaginative and enduring. And then there were the album’s innovative songwriting, multi-layered arrangements, ping-ponging production, unprecedented approaches to tones, chord voicings, and solos. . . . In short, Are You Experienced surprised everyone. During his remaining three years in the spotlight, Jimi would further refine and redefine the role of the electric guitar in rock, R&B, and blues settings.

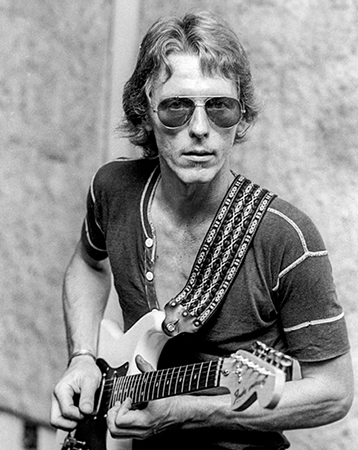

Fast forward to 1983. Synthesizer-saturated pop ruled the airwaves and singles charts, while harder rock and especially blues music seemed to be in a tailspin. Even the most venerable of bluesmen—John Lee Hooker, Muddy Waters, and Johnny Winter among them—had experienced drops in album sales and bookings. Then, like a bolt of lightning, Stevie Ray Vaughan arrived on the scene. The native of Austin, Texas, struck first with his Albert King–inspired licks in David Bowie’s “Let’s Dance.” His subsequent debut album, Texas Flood, rapidly made him the most important American blues-rock guitar hero since, well, Jimi Hendrix. For years to come, B. B. King, John Lee Hooker, Buddy Guy, and others would credit Vaughan for revitalizing interest in their music.

Like his hero Jimi Hendrix, Stevie Ray Vaughan was part bluesman, part rock and roller. And Stevie, bless his heart, was always quick to credit the musicians who influenced him. These ranged from lesser-known figures such as Larry Davis, who recorded the original “Texas Flood,” to movers and shakers like Chuck Berry, Albert King, Buddy Guy, and Albert Collins. But no influence loomed larger in his repertoire than Jimi Hendrix, many of whose songs he mastered note-for-note. He recorded live and studio versions of “Voodoo Child (Slight Return),” “Little Wing,” and “Third Stone from the Sun,” and often played Hendrix songs in concert. When I contacted Stevie to ask if he’d be willing to do an interview about Jimi Hendrix, he readily agreed. On February 9, 1989, he called me during a break from sessions for his album In Step.

When did you first become aware of Jimi Hendrix?

The first time I ever heard his name was when my brother brought a record of his home in the mid-’60s. I guess it was around ’67, ’68. And Jimmie had found it in a trash bin! Behind it. He was playing a gig at this [television] show in Dallas called Sump’n Else, and he found this record. He recognized it because he’d seen a little blurb in a magazine, just a short paragraph about Jimi Hendrix. He knew he was supposed to be something really happening, and he just happened to see this record that had gotten thrown out with a bunch of other stuff, because it didn’t fit in with the show perfectly or something, you know. And he brought it home and put it on the record player, and we just about—what can you do? [Laughs.] What can you do but say, “Yeah!” It really knocked my socks off.

I’m not sure exactly the year, and I’m not sure which song it was. It’s kind of a blur, because around the same time my brother Jimmie, he had this knack of figuring out who was really happening. And why! [Laughs.] And he would bring home these records. It seemed to me that Jimmie would all of a sudden bring home stuff, and it would be months before you would hear it anywhere else. He would bring home so much of it. He would get into a certain style of music, and he would bring a lot of that stuff home about the same time. It just seemed as if for some reason he could just come up with a style and all of a sudden he had all the ifs, ands, and buts around it. All of the things of different people who were in the same school—that went to school together, you know, instead of a different school. He would bring home all these things at the same time, so a lot of the different influences that were on Jimi Hendrix, I heard those things at the same time.

So you were listening to people like Albert King and hearing the relationship.

Albert King and Lonnie Mack and Albert Collins and Muddy. Jimmie would bring home all that stuff at the same time. It seemed as if it was like within a month or two.

Did you sit down and learn to play from that first Hendrix record Jimmie brought home?

Sure! Hey, man, I remember getting my little stereo—it was an Airline with the “satellite speakers.” That’s what they called them, but they were really these cardboard boxes with a long wire. I would set that up, mike that up. I had a Shure P.A. in my room—this is in my bedroom. For some of my first gigs, I’d go and rent like four Super Reverbs, and I’d have all this set up in my room. [Laughs.] Of course, the parents were at work. I would go in there and floorboard it, you know. Dress up as cool as I could and try to learn his stuff. It all went together. I would try to learn his stuff, and I did the same thing with a lot of B. B. King records. I think back and I must have really—if somebody had walked into the room, they probably would have gone, “What are you doing?!” Because I wouldn’t stop at one place—I’d go for every bit of it I could find.

You’d go for all the tricks?

I remember doing it a lot with Axis: Bold as Love, even though I didn’t have the phasing deals, and I’m sure I didn’t have a lot of the sounds. But some of them I could find.

Were you playing a Stratocaster?

Well, at different times, different things. Jimi had a Strat, and a lot of times I would use a Telecaster, but I had a little bit different pickups. I’d rebuilt the guitar myself, so there was some blood in it, you know. I would go as far as I could to get as close as I could.

Did you think of Jimi as coming out of the blues tradition?

Some people don’t see it. Some people really do see it. See, I don’t know whether to call Hendrix a blues player along with a lot of the originals, but he did go and play with a lot of those people. He did do a lot of it during that heyday, before he got famous. It’s like he was on the tail end of something.

That whole R&B movement.

Yeah. And a lot of it wasn’t even the tail end. A lot of it was the peak of it. He was doing that stuff as it was going on, you know. See, in his music, I hear not just the newer stuff that everybody seems to think was a lot different—and a lot of it is—but to my ears, there’s just as much of the old-style warmth.

The blues style.

Yeah! Like “Red House.” I hear it in that. I hear it in just the way he approaches things. Even though he was not ashamed at all of doing some things different, I still hear the roots of the old style. I mean, not just roots, but the whole attitude of it.

Jimi’s sometimes not that far removed from Muddy Waters.

To me, he’s like a Bo Diddley of a different generation. If you were a kid and you heard Bo Diddley for the first time, back when all that was going on, wouldn’t you think that was the wildest thing you ever heard?

Yeah, sure.

Okay. [Laughs.] I’m not saying that Jimi Hendrix was a Bo Diddley, but in that sense, there’s not that much difference. Or Muddy Waters or Chuck Berry. It was that different. He just happened to have those influences as well.

Jimi, who was left-handed, used a right-handed guitar that he flipped over, so his high-E string had a shorter scale length than the low-E string. Could this have affected the way his string bends sounded?

Yeah. I have guitars where the necks are set up that way, and there is a difference. However, to me the bigger difference is the shape of the neck. I’ve got a left-handed neck on an old Strat that I have—someone gave me a left-handed neck—and the main thing I notice about it is the neck feels different because it’s shaped backwards. I didn’t know about it until I put one on there. The neck feels different. The tension of the strings does work well that way. One thing that I noticed that’s a lot different is where the wang bar is—if it’s on the top or on the bottom. Whether I hold it with the same grip as if it was in the other place or not, it still feels different to me at the top. It seems more approachable or something.

What have you observed about Jimi using a whammy bar while playing blues?

I think he did it cool! I think if somebody else had thought about it first, they would have done it too.

Do you think Jimi was one of the first?

Uh, no. I say that because there’s a record that I think Hendrix must have heard this guy and gone, “My God! I need to check this out!” It sounds like something Hendrix would do, except it was recorded in ’58. The album is called Blues in D Natural—it’s a compilation album—and the [catalog] number is 005. The label is Red Lightnin’, an English import. The songs are called “Boot Hill” and “I Believe in a Woman.” It’s by Sly Williams. Go get you a copy and listen to it, and you’ll go, “Shit!” [Laughs.] I’ve never heard anybody other than Hendrix get this intensity and play as wild as this guy. He uses a wang bar, and he uses it real radical in places.

Do you know anything about the guy? Where he was from?

From what I’ve been told, it’s Syl Johnson a long time ago. Now, I don’t know if it is or not, but that’s what I’ve been told by someone who’s real checked-out about their information. What it says under it [the song title] is something to the effect of “Sly Williams, guitar and vocals,” and then it says something like, “Bass, drums, and piano and horn, unknown. California? 58–59.” It’s unbelievable. It’s like this guy’s teeth are sticking out of the record! [Laughs.] It’s unbelievable. And ever since I ever heard it, every time I hear it, it seems impossible that Hendrix didn’t hear this guy. And some people seem to think that it might be him playing guitar.

I haven’t heard of that artist.

I hadn’t either. That’s the only record I ever heard by this guy.

What made Jimi’s blues playing so distinctive from other guitarists?

[Pause.] I think a lot of it’s his touch and his confidence. I mean, his touch was not just playing-wise, but the way he looked at it, like his perspective. His perspective on everything seemed to be reaching up—not just for more recognition, but more giving. I may be wrong about that, but that’s what I get out of it. And he did that with his touch on the guitar and his sounds and his whole attitude—it was the same kind of thing.

Jimi Hendrix onstage at Woodstock, 1969. (Courtesy MCA Records)

What pickups settings did he tend to go for while playing blues?

Well, I have my own ideas about that, but I tend to not necessarily get that right. [Laughs.] The way I play, sometimes I tend to play harder than I need to, therefore I don’t get as much out of it.

Tonally, I hear a similarity between your “Texas Flood” and some of Jimi’s records.

I’m trying to get as close to a natural, old-style sound as possible, and I think a lot of his tones were that way. He was just reaching for the best tone that he could find. Actually, I kind of think a lot of his tones were just that’s the way he heard them, and he didn’t have to worry about it—which is something that I do a lot!

You worry?

Yeah, I’m a worrywart! [Laughs.] Sure.

That doesn’t come across at all onstage.

There’s not a whole lot of time to get stuck in it. I know that either I can turn up or I can turn down, so if it’s not working right, I usually stomp my foot and turn it up! You know, I have a real hard time with amps, and I’m having a hard time right now with them. They keep dying.

Are you using older ones?

A combination. With this record we’re doing now [In Step], I brought thirty-two amps with me.

How can you possibly need thirty-two amps?

They keep dying like flies! I brought them for different configurations to see which ones sound the best in the studio, because we haven’t been in the studio for a long time. And many times an amp will sound good at home, and when you put it in the studio and you close-mike it, its little quirks stick out a lot more.

You hear all the buzzing and rattle . . .

That you wouldn’t necessarily hear in a concert situation. But so far I’ve ended up having to have everything I brought rebuilt—either rebuilt, or just put it back in the case. And it’s real frustrating. However, sometimes an amp when it’s dying, it sounds better than it has in a long time—with every last breath, it really wants to live! [Laughs.] I think the quality of the amps for guitar and for warm sounds, the quality of the parts themselves, used to be better. Therefore they worked better. And with some of the old effects, when they don’t work properly, that’s when they sound so good.

You never found one amp that had everything you’re looking for?

I bought these Dumble amps—I bought the first one because I was really amazed. After it broke down the first time, it’s never sounded the same. I’ve bought several of them, and every one of them sounds different and is built different, and I keep wanting the same one that I bought in the first place.

A final question about Jimi Hendrix. Right now, he’s more popular than he ever was during his career. He’s selling more records, getting a lot of coverage in the press, his videos are on TV. Why is this?

He’s not putting out more things. It’s a good question. A great question. Why might I think so? I think a lot of people need what he had to offer musically—there was a lot of honesty in it. Yeah, there was a lot of drugs and things, but people are looking back because they miss something that’s here. A lot of people tend to look somewhere else for something that they want to fix them. His music, though, is wonderful. It’s full of emotion. It’s full of fire. At different points it’s full of different things. It’s full of light and heavy things, you know, feelings. By “light feelings” I mean uplifting feelings, and “heavy”—well, you know what “heavy” means! It could mean anything from one day to the next, really. But I think a lot of people miss what his music was doing for them. A lot of new people are coming around to going, “What’s this?!” In very few instances has anybody surpassed what he did. And it should be popular! It’s a damn shame that he’s dead and gone, and now is when people are listening. But, at the same time, I’m glad they’re listening!

CODA: Stevie Ray Vaughan remained devoted to Jimi’s music for the rest of his life. On August 26, 1990, he gave his last concert with Double Trouble, concluding the set with Jimi’s “Voodoo Child (Slight Return).” He then joined Eric Clapton and others for a final encore of “Sweet Home Chicago.” Soon afterward, Stevie Ray Vaughan perished in a helicopter crash.