13

Gregg Allman: “My Brother Duane”

During an extraordinarily fertile five-year period, Duane Allman evolved from a teenager struggling to find his sound to a top-flight session player and the founder of the band that bears his family name. He set new standards for bottlenecked slide guitar, paying homage to its blues roots and casting it in previously unexplored directions. Decades after Duane’s death, the majesty and influence of his best work—several of the Muscle Shoals sessions, the Allman Brothers Band’s At Fillmore East and Eat a Peach albums, Derek & the Dominos’ Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs—remains undiminished.

Jerry Wexler, Vice President of Atlantic Records while Duane worked as a session man at Fame Studios in Muscle Shoals, offered this assessment: “Duane was a complete guitar player, he could give you whatever you needed, he could do everything. Play rhythm, lead, blues, slide, bossa-nova, with a jazz feeling, beautiful light acoustic—and on slide he got the touch. A lot of slide players sound sour. To get clear intonation with the right overtones—that’s the mark of genius. Duane is one of the greatest guitar players I ever knew. He was one of the very few who could hold his own with the best of the black blues players. And there are very few—you can count them on the fingers of one hand—if you’ve got three fingers missing.”1

With the founding of the Allman Brothers Band in 1969, Duane became the figurehead of what came to be known as “the Southern sound.” He and his brother Gregg carried their deep-felt love for Southern blues and R&B to rock audiences, just as Johnny Winter and British bands such as the Yardbirds and Rolling Stones had earlier in the decade. Playing side by side, Duane and co-guitarist Dickey Betts popularized the use of twin lead guitars playing in harmony and doing counterpoint lines in a rock setting, as heard in the Fillmore East version of “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed,” which ranks among the greatest live performances in rock guitar history.

For most of his life, Duane Allman was inseparable from his younger brother Gregg. Raised by their widowed mother in Nashville and Daytona Beach, they learned music together and played side-by-side in bands. They spent their journeymen days in the Daytona Beach-based Houserockers and then toured as the Allman Joys. In 1967 the brothers moved to Los Angeles to form the Hour Glass. They finally hit their stride in 1969, with the formation of the Allman Brothers Band. In less than three years, Duane was gone, killed in an October 1971 motorcycle crash. Ten years later, assembling material for an as-yet-unwritten Duane Allman biography, I interviewed many of his bandmates, friends, and peers. The most poignant, with Gregg, took place on July 6, 1981. Gregg began the conversation.

GREGG: I think that’s really nice, man, that you want to write about Duane.

Can you fill in the early years for me?

Okay. Alrighty.

Duane was a year older than you?

A year and eighteen days.

Were you the only two kids?

That was it.

Your father died when you were young?

Ah, yes. He died in ’49. I was two and Duane was three.

Is your mother still alive?

Yes, she is.

Did anyone in your family play music?

My father sang, but not professionally. He sang pretty well.

Did you have instruments around the house when you were young?

No. No, we didn’t. When we started school, we both wanted to get into the band. We went to military school, and we both wanted to play trumpet, and we lost interest in it. My mother always called it her folly, because back then $200 for a trumpet, you know, that was quite a bit.

You were raised by your mom?

That’s right.

Did she work while you were kids?

Yes, she did. That’s why we had to go off to military school.

You began playing guitar before Duane?

Right.

How did you get started with that?

We moved from Nashville in 1957—I guess I was eleven years old, about to turn twelve. No, wait a minute—I may have been younger than that. Anyway, we moved away from Nashville and moved to Daytona Beach, Florida. But every summer we would go back and visit my grandmother and stay there for the summer. We really missed Nashville because we grew up there, you know. She lived in this housing project, and there was this guy across the street. And he had an old Belltone guitar, which later, I think, turned into Silvertone—I’m not sure. One hot summer day he was sitting on the porch, and I walked over there and asked him if I could pick it up. He said sure. The strings were about an inch and a half off the neck—one of those bleeders, you know. So I just got really enchanted with this. By this time, this is like 1959.

So when I got back home, I thought, “Well, I’m gonna get me one of those guitars.” I didn’t know which end of it to play, but there was something about it that just really intrigued me. Because he’d sit there and he’d play “Wildwood Flower” and “Long Black Veil”—I think that’s the only two songs he knew. He knew very little, a real country dude. Jimmy Bain—that was his name. So I got me a paper route and worked on it from March of ’60 until about the end of school, right when school let out. Cleared all of $21, something like that—they got me on the office payment: “Yeah, we pay at the office,” right? You know how that goes. So I rode my bicycle over to Sears. There was a Silvertone there that I wanted. It was $21.95. And the guy wouldn’t trust me for the ninety-five cents, so I had to go home and borrow it from my mother. I rode back over the next day and bought it and started playing it and playing it. I got one of those Mel Bay books, and I didn’t eat or sleep. I didn’t do nothing but play that guitar. I just was crazy about it. I learned how to make a barre chord, and that really started it.

Was that an acoustic?

Right. This friend of mine turned me on to some Jimmy Reed albums and taught me that lick. So then my brother, he says, “What do we have here?” So I taught him what I knew, and he picked it up real quick. I mean, he was real sharp. So he quit school.

How old was Duane then?

Well, I started playing when I was twelve years old. I jumped a little time on you there. It’s been a while. I started playing when I was twelve, and I got my first electric guitar that November. November 10, 1960. It was a Fender Musicmaster. It was really easy to play. By then I’d met other guys that had guitars that had been playing longer. It was just like more and more. I really got turned on to Chuck Berry and Jerry Lee Lewis and Little Richard, Presley—you know, the whole rock-and-roll thing. And then I met this black cat named Floyd [Miles]. By this time Duane, he had to have one. So to keep us from fighting, mom got him one, right? It was a Les Paul Junior, one of the old ones. It was solid, a real thin body, one of those purple ones. Just one black pickup on the back [near the bridge]. So we started playing together, and we really became friends at that time.

Were you like typical brothers before then?

Oh, yeah. Fight every day.

What did Duane want to be when he was little?

Uh, that’s a good question. I’m not sure. He didn’t like school, but he loved to read. He was always reading something. He read books like Papillon, [Tolkien’s] The Lord of the Rings trilogy. He read all kind of stuff, just anything. He liked real adventurous stories and fiction—stuff like that.

Was he a good kid?

No, he was a rascal. He was a rascal. So we put a band together. Well, first we joined a band that was already together. It was called the Houserockers and the Untils. The rhythm section, the band, was the Houserockers, and the three black singers up front were the Untils.

Were both of you playing guitar?

They only needed one guitar player, so we switched off every other night. This was like the summertime of 1963. I was like a junior in high school, something like that. Anyway, one of those black singers was Floyd, and I watched him because I really dug his singing. See, in the beginning, the first band that we put together ourselves was called the Shufflers. I played lead guitar and Duane sang. And then after he quit school, he’d stay home and, man, he learned it fast.

He played all the time?

All the time.

Did he cop off of records or make it up himself?

Both.

Do you remember his favorite solos or players?

B. B. King—he loved B. B. King! Over the years he loved everybody from Chuck Berry to Kenny Burrell. I mean, you name it. He dug everybody. Back then, Johnny “Guitar” Watson—he liked him. He got into that real old blues stuff, loved Robert Johnson. He just loved any kind of guitar playing.

He never had lessons?

No. The only lessons he had was us sitting around the house, trial and error. And then he had a friend named Jim Shepley. I think Shepley was a couple of years older than him and had started a couple of years before. He’s the one that turned us on to Jimmy Reed records. He had a bunch of these hot licks down. I thought, “Man, this guy is something else!” So he sat with him all the time. Before he quit school, they’d both skip school and shoot pool and play guitar. He learned a whole lot from Shepley, and that was probably his best friend back then.

Is Jim Shepley still around?

Yeah, he sure is. I hope he reads this. I think he lives in New Haven. He was in a band with Bob Greenlee, who used to be with Root Boy Slim and the Sex Change Band. I’m not sure if Shepley was in that band or not, but I know Greenlee was. And usually where Greenlee was, Shepley was. But I don’t think he’s doing much at all now. It’s been years. I remember at one of the first few gigs that the Allman Brothers played, we played in New Haven, and sure enough, Shepley and Greenlee were both there. Duane was just—you could have knocked him over with a feather, man. It was great!

Was Greenlee another guy who played with Duane when he was young?

Right, he played in the Houserockers.

What were your other early professional experiences and bands leading into Hour Glass?

Well, after I got out of high school in ’65, we had a band called the Allman Joys.

Did you do much touring?

Touring? I don’t know if you could call it that. We did what they called the “chitlin circuit”—you know, Mobile, Alabama, at the Stork Club. We worked like seven nights a week, six sets a night, forty-five minutes a set. It was four of us, and we made $444 a week.

Was it unusual for a white band to be playing the chitlin circuit?

Oh, no. “Chitlin circuit”—that means just the clubs and beer joints.

Did the Allman Joys record?

We recorded one song, one 45. We recorded it at Bradley’s Barn in Nashville, which is now burned down. It was “Spoonful” by Willie Dixon.

Did you sing it?

I sure did. And it was a terrible recording.

What happened after the Allman Joys?

Let me see. One of them got drafted, one chose to go his own way, and so Duane and I met up with Johnny Sandlin and Paul Hornsby and Pete Carr. They had a band called Five Minutes. We formed a band, and we called it the Allman Joys for a while. And then we thought, “Well, that’s wrong,” so for a very short time we called it the Allman-Act. And Bill McEuen came through St. Louis, where we were playing. Johnny McEuen of the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band is his older brother. They took us to L.A., and they came up with the name Hour Glass.

How do you view your period in L.A.?

That period with the Hour Glass? It was pretty scary, you know, because I’d never been past the Mississippi. I’d been to New York once. I don’t know. It just seemed like it was forever away. We didn’t play much. For some reason, there was no clubs or anything around there to play in. I mean, there was, but . . . Our first gig was with the Doors at—well, it’s the Aquarius Theater now, but at that time it was the Hullabaloo club. And that scared me to death! I could barely sing. My knees were knocking together, because there must have been two thousand people in that place. The whole thing just kind of turned sour. Both albums came out, and they’d hand us a washtub full of demos and say, “Pick out your new album.” All this time now, I was songwriting. I did get a few on those two albums. I don’t know if you’ve heard those albums or not.

The ones with “Out of the Night” and “Power of Love.”

Yeah, right.

They’re still selling them.

Yeah, yeah. That’s what I hear. In the beginning, when we were in St. Louis and they made us a proposition, I said, “No, let’s don’t go.” Duane said, “Yeah! Let’s go! Let’s go! Let’s do it.” So we went. I guess we were there for, oh, part of ’66, ’67, ’68—for about two and a half years. And Duane just finally said, “Man, I’ve had it with this bullshit. I’m leavin’. We can take the band and go on back home where we belong—right down South.” We owed Liberty Records about $40,000. They said, “Well, we’ll let y’all go, but we’ll put a lawsuit on you. But we won’t do it if he stays”—pointing to me, right?—“to work with our studio band.” So I stayed. And the rest of them, they really didn’t like it. They were all cussin’ me on the way out the door. They thought I wanted to stay out there, which I did not. So there was no lawsuit, and I cut two records with them. They’re with a twenty-piece orchestra. I hope you’ve never heard those.

No, I haven’t.

Please, don’t. Anyway, so I stayed out there another eleven months, and that’s the longest I’d ever been away from my brother. That’s when I wrote “[It’s Not My] Cross to Bear.” I was staying with this chick, and she was really running me around. I wrote “Black Hearted Woman” while I was out there. So anyway, one Sunday morning my brother called me on the phone, and he said he had this band together—had two lead-guitar players. I thought, “Boy, that’s weird.” He said, “And two drummers,” and I said, “That’s real weird!” “And a bass player.” And he said, “But everybody is pretty much into their axe, and nobody as yet has written much, and they don’t really like to sing. So why don’t you come on down here and round this thing up and send it somewhere.” Which is probably the finest compliment he ever gave me in my life. I said, “Let me hang up this phone, man. I got to get going.” I beat feet over there as fast as I could to Jacksonville. And that was the Allman Brothers’ start. It was March 26, 1969.

The difference in sound between the Hour Glass and the Allman Brothers is just amazing.

Yeah, it is. I mean, it’s been a long time since I’ve heard any of that Hour Glass stuff, but when I hear it I can’t believe it.

In between this time, was Duane playing in Muscle Shoals?

Right. He was just on the staff down there at Rick Hall’s.

Did he ever mention what his favorite studio projects were?

He liked to play with Wilson Pickett—I know that. And he loved playing with Aretha, and he loved King Curtis. They was real tight. And he loved the Herbie Mann. He liked all of them. I think Layla was probably his favorite.

Did he have much to say about working with Eric Clapton?

Oh, yeah. Yeah. I was there when it all happened. Our whole band was there. See, we were playing in town, and Clapton came out to the gig.

Was Duane nervous?

Scared him to death! He came and sit right down in front, right on the grass. Of course, Clapton, every time you see him he looks different. I didn’t notice him until toward the end, and I got shaky myself. Tommy Dowd was with him, and Duane asked Tommy if it’d be alright if he came and watched part of the session. And Clapton said, “Watch? Hell, come on and play!”

Were you there while they were recording the song “Layla”?

I was there for part of the first of it, and then I had to go back up to Macon. I came back down at the end of it. At one point of it, toward the end, we all got in there—both bands—and did a real long jam. We got it on tape. It’s like a medley of blues songs.

It sounds to me that Clapton pushed Duane into playing beyond what he was doing before then.

You know, Duane liked that. He always said, “I like somebody onstage kicking me in the ass, so I’ll do better,” which I like myself.

It sounds like a lot of parts on “Layla” are Duane’s rather than Eric Clapton’s.

You got it right. On that song itself, he’s got twelve tracks on there.

In something like “Why Does Love Got to Be So Sad?” sometimes it’s hard to tell them apart, and then all of a sudden Duane’s “Joy to the World” lick comes in.

Oh, yeah!

When you got the Allman Brothers Band together, some of the press proclaimed Duane the father of the band. Is this accurate?

That’s real accurate.

How much musical direction did he provide?

He had to do with a lot of the spontaneity of the whole thing. He was like the mothership, right? He had this real magic about him that would lock us all in, and we’d all take off. Yeah, he really had that quality about him.

How much time did the band spend playing together before the first album?

Oh, we used to play every day. Every day. Because for the first album, they said, “Y’all got two weeks. Get in there and do it, and get out.” Yeah, we cut that album in two weeks.

What was the first big break for the Brothers?

When it got together! [Laughs.] He [Duane] always felt, and I learned from him, that if you lay down a sound, if it’s a hit in your heart, it’s a hit. I don’t care how many it sells or how many like it or whatever—play what you want to play and stick to your guns. That’s how we got out of playing Top-40 stuff, and that’s probably what started me to writing songs. He was really that way about it. He did his thing, you know, and if you like it, fine. And if you don’t, fine.

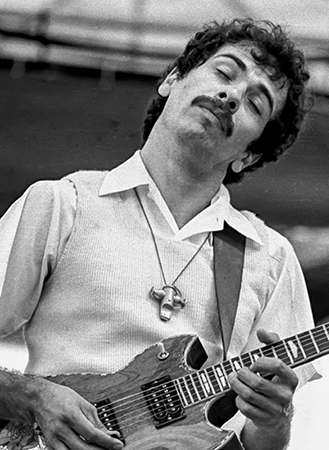

Duane Allman, late 1960s. (Photo by Twiggs Lyndon)

Did Duane take stardom easily?

Um. [Long pause.] Well, the real heavy stardom. . . . Let me see. He was pretty shy about that sort of thing. No, he didn’t. He was just one of the gang, man. The same dude that hung around with Shepley and shot pool. He thought about it the same way I do—you’re just another person.

What do you think were the best representations of Duane’s live and studio sounds with the Allman Brothers?

The best things he did? Wow, man, I like ’em all. He did some incredible things on—it wasn’t studio—“Mountain Jam.” “Don’t Keep Me Wonderin’”—there’s some good slide on that. Let me see. “Revival.” Things like “Leave My Blues at Home.” I know what! “Dreams.” He did one hell of a job on the solo on that. Yeah.

Sometimes in his solos—like on that Boz Scaggs album and at the end of “Layla”—he did that really high part that almost sounds like birds.

That’s what it was supposed to be! He put the bottle way up there by the top pickup.

Did he have any unusual recording methods?

He changed a lot. Like down in Muscle Shoals, he’d take a [Fender] Princeton amp and turn it on full blast, you know, and cover it with baffles. He was always working with Fuzz Faces and everything like that, and then he threw all that crap away and got the right amps for the right sort of thing. Like when he started working with Marshalls, he found out that the 100-watt was not it, so he used 50-watt cabinets.

Did he play really loud?

Yeah.

Was he usually standing up when he played?

Oh, yeah. Oh, yeah.

What was the difference between what he was playing on records and what he did by himself?

He did a lot of country blues when he was by himself, on a steel-bodied National or a Dobro, something like that. A lot of time he’d go into the bathroom, you know, with the tiles. I’ve got a picture of him leaning against the sink, and you can see the toilet there and the toilet paper roll. He’s sitting there with a Les Paul. I can hear it, you know. [Laughs.] It’s a great picture! I’ve got one and Dickey’s got one.2

What were Duane’s favorite guitars?

Well, for a long time, he played a Telecaster with a Stratocaster neck. This is during the Hour Glass. In the Allman Joys he played a 335 [Gibson ES-335]. Then he got a Les Paul, and he loved that Les Paul, and an old SG that he played slide on.

Did he play much slide on the Les Paul?

No, not at all.

Just on the SG?

Right. Wait—I might be wrong about that. A couple of times, he might have. Dickey could probably tell you more about that.3

Where are Duane’s guitars now?

I’ve got some of ’em. Dickey’s got some of ’em.

There’s a story that Twiggs Lyndon traded you a car for one of Duane’s Les Pauls?

Yeah, I traded it to him for a car. See, the guitars I play have to have a wide neck on them. That particular Les Paul had a narrow neck on it, plus it was a 1939 Hypercoupe, plus it’s Twiggs. I mean, you know, Twiggs and Duane were real close. I guess you heard about Twiggs.4 His mama has it now. And my brother had an old Gibson, 1929 J-200, an oval hole and with an archtop—I’ve got that one.

What happened to his National?

The one that’s on Dickey Betts’s cover? Dickey’s got it in his living room.

Toward the end of his life, who were Duane’s best friends?

John Hammond. All of us, of course. He hung out with us a lot. King Curtis, until he got killed. Johnny Sandlin.

I recently interviewed John Hammond about Duane, and he had some beautiful stories to tell.

He’s a beautiful man.

Was Duane hard to work with?

Not at all.

I know if I had to be in a band with my brother . . .

No, it wasn’t brothers then. I mean, it wasn’t brothers as you would think “brothers.” He really respected what I did, and I respected what he did. He’d lean right against the organ. One thing he did, he hardly ever looked down at his guitar when he played slide. How he did it, I don’t know. He just knew where he was goin,’ I guess, and he’d look back at me and make me sing harder. And I loved it. But every time I walk up on the stage, I still feel like he’s standing right there next to me.

The spiritual connection is still strong.

Very. There’s not a day goes by I don’t think of brother Duane.

What was Duane like outside of being in the band and outside of music?

He was pretty quiet. Homebody. He liked to bass fish. He wasn’t very much a sportsman at all.

Did he play a lot in his spare time?

Oh, yeah. Yeah. He’d listen to music all the time. Any time you’d walked into his house, you’d hear music playing.

Did he have a big record collection?

Oh, yeah.

Did Duane ever say what he wanted his legacy to be?

No, he never talked much about dying.

How do you now view the period of the band when Duane was in it?

Very happy days. We didn’t have much money. Well, Duane had a substantial amount from sessions, but nobody was rich. But we didn’t care because we were playing our music, and we’d come up with a new song. You know, when a new song is born in rehearsal—that’s why I like rehearsals just as much as I do recording, just as much as I do playing live. Because when a new song hatches out and it works and clicks, man, it’s like Christmas time.

Do you have any favorite memories of Duane?

Yeah, he was one hell of a cat.

Anything else you want to cover, Gregg?

[Long pause.] Only that I think his music will live on a long, long time, and I’ll support it as long as I’m around. And I loved him.

CODA: Following Duane’s death on October 29, 1971, the Allman Brothers enlisted Dan Toler to fill in on slide guitar. The group disbanded in 1982 and reformed with great success in 1989, with superlative slider Warren Haynes stepping in to recreate Duane’s parts and carry the band in new directions. During the late 1990s Derek Trucks, son of one of the band’s original drummers, joined the lineup and more than held his own on slide guitar. In 2015, the Allman Brothers announced that they’d given their final concerts. Since then, Gregg Allman has toured under his own name.