18

Eric Johnson: The Journey Inward

As an editor for Guitar Player magazine, I’d often hear about superb guitarists who, for various reasons, were largely unknown outside of their hometowns. In the early 1980s, this was clearly the case with Eric Johnson. What instantly set Eric apart, though, was who was talking about him. Two quick examples: Jeff Baxter, studio ace and veteran of the Doobie Brothers and Steely Dan, told me in 1980: “Eric Johnson from Austin, Texas—this kid is just amazing! He’s twenty-three. When I heard a tape of him, I went ape. This might sound silly, but if Jimi Hendrix had gone on to study with Howard Roberts for about eight years, you’d have what this kid strikes me as.”1 Steve Morse, 1982: “Eric Johnson is one of the best electric guitarists anywhere. He’s so good it’s ridiculous. I’m not kidding—he’s better than Jeff Beck. Eric destroys people when he plays. We’ve played gigs with him, and it put a lot of pressure on me when it came our turn to play. All I can say is that if he had an album out, he’d be the first one on my list of required listening.”2

In 1982, when Eric was entangled in a contract that curtailed his performance opportunities, I sought him out for his first nationally published interview. It was unusual for Guitar Player to publish a feature on a guitarist who didn’t have widespread recognition or even an album to promote, but all it took was a pair of ears to hear that Johnson already was an extraordinary musician. As we spoke, what impressed me even more was Eric’s humble attitude and steady focus on the spiritual and intuitive sides of musical creation. “I always try to connect myself with what I’m feeling inside and hearing inside,” he explained. “I think that’s the best way to try to achieve your own feel for the guitar. It’s like intuition: ‘intuition’ is like the ‘tuition from inside.’ And if you get with that, your own self will show you how to play guitar.”3

For Eric Johnson, the creation of sublime music has always been about the journey inward, an approach shared by John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Wes Montgomery, Jimi Hendrix, and others visionaries. Over the years, Johnson’s unwavering devotion to perfecting his art has become as legendary as his near-fanatical attention to the minutiae of his gear. This is evident in his songs, interviews, instruments, and the way he plays guitar. As Stevie Ray Vaughan put it, “The guy has done more trying to be the best that he can be than anybody I’ve ever seen. He plays all the time, and tries to get his instrument in perfect shape all the time. He works hard on his tone, sound, techniques. He does incredible things with all kinds of guitars—electric, lap steel, acoustic, everything. Few people understand that when the guy was fifteen, he was playing Kenny Burrell and Wes Montgomery stuff, and he was doing it right—that’s pretty cool. Eric is a wonderful cat. He’s always been one of my favorite people in the world, as well as one of my favorite guitar players.”4

Eric has released many solo albums over the years, with 1986’s Tones, 1990’s Ah Via Musicom, and 1996’s Venus Isle being among the very best. Near the end of our first interview all those years ago, I asked him what he’d like to accomplish. “I’d like to have my own studio,” he responded, “and be able to record albums the way I want, which is really experimenting with guitar. I’d just like to contribute some new things for guitar.”5 Eric, I am happy to report, has achieved these goals. Our mutual friend Max Crace was on hand to shoot photographs when this October 13, 2012, interview took place in Eric’s spacious Saucer Sound studio in Austin, Texas.

What is it about Stratocasters from 1954, 1957, and 1958 that is so special for you?

That’s a really good question. I’ve always wondered what it was. I think it’s several things. I think that they had a shipment of wood at Fender that was real special—that was one thing. That kind of wood is really hard to get nowadays, and even though it’s a solidbody guitar, it makes a difference in the way the sound travels. You know, when you go out to a restaurant and you eat a meal and you feel really good, it might have been because the person preparing the meal had all this great emotion and vibes. It’s like whatever we do goes into what we do. You know what I mean? On a very subtle level we can feel that. And the other thing that’s kind of undeniable is it was a point in time where the electric guitar was so new. Every week you’d hear somebody on the radio or on a record and say, “I’ve never heard that!” It was so new that it had that kind of birth energy to it. It’s almost like when you’re in the studio and you record that first track, and it’s got this magic. And then you go back and do it ten times, and it’s, “Oh, it’s actually better now, but it’s not as fun to listen to or it’s not as good.” So I think those two factors play into it. They’re still making great instruments, but it’s hard to recapture those two issues as time rolls on.

Do you think it’s possible that the fact that they’re more than a half-century old and have aged and become more of a unit . . .

One unit—yeah, I think so. Yeah, you’re right. Definitely. That’s why whenever I see a vintage instrument, I always think it’s cool if somebody doesn’t take all the parts off and put them in a big box and put everything back together somewhere else, because it’s had forty years to be the way it is and grow into that entity. I’m kind of ridiculous about that: “Oh, make sure the screws go back in the same place,” you know. And the only reason for that is because they’ve been there for forty years, and I think they do what you say. All these parts, because they’ve sat and they’ve had time to gestate, it turns into a complete entity. And if you do disturb that, it does affect the sound.

When you purchase an old guitar or trade for one, what do you look for?

I go for a particular thing. I like it where when you’re playing with a clean tone, the sound is real crisp but it kind of punches out. But then when you go to the lead sound, it kind of sucks in, more like a Gibson does. They have more of this kind of folding-in character to them. So it’s almost like you get the best of both worlds. You get that real pronounced EQ clarity for the rhythm tone, but the more you push the amp or you push the guitar, it starts folding in upon itself. It’s a response of the parts and the wood and the way it resonates. Some guitars will do the exact opposite—they’ll kind of be a little bit edgy-sounding on the top end when you’re on the clean tone, and then as you push it more and more, they start going out, so they bloom out. As they bloom out instead of folding in, you hear every single pick attack. And it’s not only the sound of the pick attack which bugs me a little bit, but it’s also the fact that if you’re pronouncing that pick attack so much, the note is not recovering quick enough for you to go to the next note. One way is in favor of your picking, and it’s kind of more like an impulse ballet thing that breathes out and folds back in the same sync of your pick, and the other way is like you’re fighting it and you’re actually tripping-up your sound.

Are you careful about how the instrument sounds acoustically?

Usually when they work right, they sound better acoustically too. Yeah, you can kind of hear it sometimes.

Do you have any gear that’s so precious you won’t take it on the road?

You know, I do, but every once in a while I play it anyhow because I try not to get too hung up in that, because I just figure, well, the whole reason I got it is to play it. I bought this old Marshall combo that I’ve been using on the road, and it’s really sweet and original and in great condition. The first thing I do is take it on the road and start touring with it. [Laughs.] I don’t know if that was smart. Hey, you know, I bought it to play, so I’m just gonna play this thing. I don’t know. I have some guitars that I don’t typically take out, but it’s just because I really haven’t used them on the road that much. Most of the stuff I’ll use.

Among all the guitars you have, are there any that you’d site as the two or three most precious?

Yeah. I have a 1980 [Martin] D-45 that my dad bought me, and it’s real sentimental, because my dad’s passed away. I got it when it was brand new. When I had those instruments stolen in ’82, he bought me this guitar to replace the acoustics I lost. It had been in Heart of Texas Music for a while. I think it was an ’80 or an ’81, but I got it in ’82.

Did he take you to play it first, or did he just surprise you?

I went down to Heart of Texas, and they had two of them. I tried them both out for a few days, trying to decide which one to keep, and took the other one back. Yeah, so that’s a real special guitar. And I have a guitar that Chet Atkins gave me that’s a Del Vecchio [wood-body resophonic]. That’s real special to me. You remember Bill Maddox, the drummer that was killed? In his will he had an old Strat that he willed me, so I would never . . . that’s real special.

Do you have a particular guitar that you’ve written a lot of songs on?

That Martin I’ve written a lot of songs on. Let’s see, what else? Yeah, that’s probably the one that I have that I’ve written a lot on. All the acoustic songs that I do pretty much I wrote on that. Some of the electric tunes I wrote on that ’54 Strat I had that I don’t have any more—that I wish I had! I shouldn’t have gotten rid of it.

The Virginia?

Yeah. There were four women in ’54—Mary, Virginia, and I don’t know who the other two were.6

Where would they sign the guitar?

There’s a piece of masking tape right down inside here [indicates the inside of a Fender Stratocaster’s body cavity].

So that’s near the pickup selector.

Yeah. And it’s only in ’54 they did that. It’s really interesting, man. You know, I don’t even know if I want to say it because everyone will go out and say, “Oh, ’54!” But they really are—they’re different than the other ones. [Smiles, adds with humor] But they’re not any good! They’re horrible! [Laughter.] They’re worth about $200, so . . .

Send them to me and I’ll take them off you!

Yeah.

What are your favorite Gibson guitars?

Honestly, a 335. I know there’s a Les Paul out there that I’d love to own, but I’ve owned so many and I’ve never kept a single one of them. And it’s not that they’re not great. There’s a certain thing about my technique or something, or the weight, that I haven’t quite found the right one for me. But they’re great. I mean, my heroes all played them, but I’ve never found the right one to settle on. But I’d say a 335. And I have an SG that sounds great—I was never really a huge fan of SGs, but I stumbled on this guitar, and it has a great sound and it stays in tune, so I like it too.

Have you used it for slide, like Duane Allman?

No, I haven’t.

The SG is interesting because you can easily get so high up the neck.

Yeah, yeah. They’re great. I can’t believe this one stays in tune, because every other one I’ve ever played never stayed in tune. But this one seems to.

Speaking of SGs, I understand that you enjoy Angus Young’s playing.

Oh, yeah! He’s great.

Doesn’t he have one of the best vibratos in all of rock and roll?

Absolutely. He’s awesome! I don’t know how he plays running around like he does, either. He sounds like somebody that is sitting down concentrating really hard. Yeah, he’s a great player.

When you think of the guitarists you admire, who would you put in the category of people who have the million-dollar vibrato?

Definitely Eric Clapton and B. B. King. Mick Taylor, like from the Mayall days. You know, in certain ways Peter Green. And then the slide stuff that Robert Johnson did, the way he would do that. And then Django Reinhardt for his own style. Oh, Albert King—definitely Albert King! Of course, that’s more like he’s just making big stretches. Yeah, I’d say definitely Albert King. That’s where, I guess, Clapton honed his own style. I mean, Clapton’s vibrato on early Cream stuff is pretty ridiculous. It’s pretty great.

B. B. talks about how he developed his vibrato because he couldn’t play slide well, so he decided to imitate a slide with his fingers.

Oh, wow.

He also told me that when he was a kid, strings were so hard to get that if he broke one of the Black Diamond strings, he would just tie a knot in it, restring it, put a pencil above the knot, and tie string around the pencil so it became a capo. And then he would play above the pencil until he was able to buy a new pack of strings.

Oh, my God. That’s great. I thought you were gonna say just take it and just rewrap it to the ball and tie it—we used to do that as kids. But that’s one step more. That’s even more old-school. That’s living the blues right there!

Could you describe your thoughts on the spirituality of playing music? Is it important to keep yourself pure and unmotivated by greed and ego to play at your very best?

You know, that’s a great question. I’ve thought about that before. I think that for me to play my best, I need to have myself not modulating but more in sync and focused with that aspiration. Somehow that, for me, is the gateway to feeling at peace with myself. If you’re at peace, you can travel beyond yourself. At that point, you’re available for any nuances of magic that are bombarding us twenty-four hours a day anyhow—we’re just too busy talking or distracted to hear it or feel it or see it. But it’s always there if you can get into that focus where you’re just at peace with yourself. Being like that allows me to then go pick up on something sublime. I’m always kind of searching, looking for something that’s sublime, that makes me feel better or makes somebody else feel better. But it’s not like “Oh, that’s the only way you can make art”—I don’t think it is. I think there’s a real validity for art that sometimes causes angst or dissention or uncomfortable provocation of thought. But my little niche is to try to make people feel good, to say, “Oh, wow!” I think life is hard anyhow, so why not use that opportunity?

The question is really interesting to me because I’d love to say that that’s necessary, but I guess it’s not. Maybe what’s necessary to make a really good artist is being able to turn off the switch of your self, which is just gonna just throw a bunch of paraphernalia in your path for you to trip over. Have you ever met artists and gone, “Jeez. These people are not very nice—they’re really just hung up on themselves”? Or you meet a famous actor or whatever, and it’s just like, “Wow! This is a high-maintenance person.” But they’ll walk on the set and [snaps fingers] bam—they’ll just be in touch with this God energy, and they do this amazing performance or this amazing piece of music. Some people—regardless of how they live their life or what they like or appreciate or how they conduct themselves or relate to other people—have an ability to just [snaps fingers] do a switch to where they can go beyond themselves, regardless of what their self is comprised of. So I guess it’s an enigma and just depends on the individual. I used to grapple with that, because I thought, “Well, that blew my theory of you’ve got to do all this homework.” But it’s important to work on that spiritual aspect. The other stuff, really, if we think it matters at the end of the day, we’re totally just kidding ourselves. I don’t think it does.

Do you go through a process of emptying yourself to write songs or prepare to go onstage, a letting go of the ego?

I try to, yeah. I think it gets harder as you get older. In some ways it can get easier because you’re aware of the benefit of doing that. You appreciate that benefit so much more, so you’re more committed to trying to get there and do that. But in some ways it gets a little harder because you have all this history of living. It’s like if we only had three days, we’d have a lot of extra space in the computer to make up the alphabet of our self. But if you have forty years, it’s filling up all the space, and your consciousness is that forty years. You get a little bit more solidified, you know. The more that you’ve solidified with all that history, you associate with it so much that it’s harder to just let it go. It can be more demanding on your psyche because you have all this self. But I know that the best I ever play is always when I can put all that aside, let it all go and just show up and be available. You’ve got to do that to create more significant music.

What have been your easiest and your most challenging songwriting experiences?

Interestingly enough, one of the easiest was “Cliffs of Dover.” That just came in five minutes. It’s a hard song to play, but it’s really just a silly little melody, cute little fun thing. I guess that’s why people related to it, because it is that. It was more like a gift—it just came to me. And I think some of the others—I can think of songs that I worked on forever and ever and ever. I have ones that I have been working on for years that I’ve never written, but I know are really, really good. But I never can finish them because I never can find—I don’t know how to finish them.

Where and when did “Cliffs of Dover” come to you? Do you remember the moment?

Yeah, it was like years before I recorded it—it was like the mid-’80s. I remember just sitting and practicing and getting this idea for the melody. I think I came up with [sings opening refrain]. I kind of like that, and then the rest is just I-IV-V-I with a real simple [sings another line]. It’s really a pretty simple melody. And then within a few minutes, “Oh, I’ve got a middle eight for this.”

“Zap” was another one that came quickly?

Yeah, yeah.

What do you remember about that?

I remember listening to a Frank Zappa record and it had some interesting riffs [sings them], almost like “Zap” a little bit. So I had that one riff [sings part], but I didn’t have any of the rest of the song. I used to just call it my Zappa lick—“Oh, I’ve got that Zappa lick.” So when I finished the song, I just changed it to “Zap,” because it was kind of a Frank Zappa construction.

What’s the backstory for “Emerald Eyes”?

I was just sitting down at a Fender Rhodes one day, just jamming around on a song, trying to come up with some chord changes. I liked the chord changes, and I just put a melody to it.

Did you know somebody with emerald eyes?

No. Actually, Jay Aaron wrote the lyrics to that.

Tell me about “Bristol Shore.”

That actually was a friend of mine named Judy that I was hanging out [with] at the time. She worked for Exxon Mobil. She’d fly out on a helicopter to these oil platforms in the Gulf of Mexico. And I’d gone down to Galveston to meet her, but she had to go out. I didn’t ever catch up with her. I just ended up hanging out in Galveston for the whole evening because she got an emergency call to go out to one of the platforms. So I just changed it. There’s references to it, like “she’s been delayed in the Gulf of Mexico.” I looked around, and I couldn’t say, well, “Galveston” [the title of a Glen Campbell hit]. I was looking at a map and found Bristol Bay. “Hey, that sounds cool. That’s a little bit more mysterious.” So I changed it to “Bristol Shore.”

How did “Desert Rose” come about?

That, my friend Vince [Mariani] just named that song. He called it “Desert Rose.” He gave me the idea for the title, so I started writing the lyrics.

Was that on guitar?

Yeah.

“East Wes” and “Manhattan.”

“East Wes” was just kind of a simplified version of kind of a Wes Montgomery thing. “Manhattan” was an instrumental that had kind of an urban sound to it, so I just named it that.

A lot of young players who are into rock and roll have probably never heard Wes Montgomery. Why would you recommend someone seek out his music?

Well, I can think of a million reasons for me, personally, because I love his playing so much and the way it sounded. But I think any young player should have the opportunity to listen to anybody that had a really special, unique spirit that was so powerful that what you’re feeling from what they’re doing is not so much what they’re doing, but the spirit that’s coming from behind it, that’s fueling it. And that happened with so many artists in a rarified way because they were so dedicated to that as they voiced their music through it that they paid homage to that. And they stayed in that place a lot. They didn’t go elsewhere to get fuel for their creativity. It’s important for young artists to check out any artist that was dedicated to that space almost in its entirety.

What’s really interesting is that with the ones who are, there’s such a symmetry between them. And that’s why I say it’s not really what they are doing, it’s the spirit from behind it that fuels it. It’s like the very first time I ever saw a live video of Wes Montgomery—you know, the ’65 stuff—he’s just kind of sitting there smiling and playing. And the first thought that came—and I know guitar, because I’ve played guitar my whole life—was Wes has his own sound. You wouldn’t say, “Oh, yeah, he reminds me of this rock guitar player.” Not at all. It’s a totally different thing. But you know what the first thing that came to my mind when I watched him was? “That’s another version of Jimi Hendrix,” because of the spirit. When you look at the early Hendrix stuff, like Monterey Pop—before things got complicated or he had personal issues or whatever—he’s just nodding his head and smiling and he’s “Hey! What’s going on?” and he’s playing. And Wes is doing the same thing. That same energy was fueling Wes’ playing, and that same energy was fueling Jimi’s playing. With Louis Armstrong, you can pick up that same thing. It’s all the same. You find people that are so different, there’s something that you’re picking up in your heart. And I think it’s because they stay real close; they’re fueling themselves off that really rarified space that is the best place. And it becomes more of a spirit that infuses it. It’s bigger than what it is. All kids should seek out people that really are committed to that.

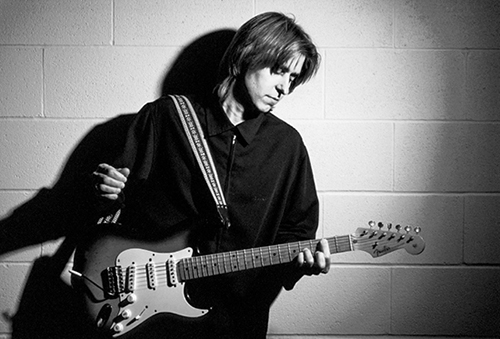

Eric Johnson in Seattle, November 8, 1996. (Jay Blakesberg)

Would you put John Coltrane and Miles Davis there?

Yeah, absolutely. Yeah.

When you listen to Wes, do you prefer the beautiful, melodic “Down Here on the Ground” type of material over when he’s going further out and pushing the boundaries?

You know, I love it both. I like it both. At one point I tried to say, “No, okay, I’m not gonna like Down Here on the Ground anymore. I’m only gonna like the Riverside recordings and Movin’ Wes and Smokin’ at the Half Note and the Wynton Kelly stuff. I’ve only got to like that. I can’t . . .” I’m sorry, I like Down Here on the Ground. It’s got an incredible vibe. If you put on Down Here on the Ground and you drive around at night, it’s just great. And it’s another thing. It’s got that spirit. They’re great songs, regardless. Yeah, it is on CTI and it is pop and it’s homogenized and all that, but so? Music is music. There’s great music. There’s some killer songs on The King and I soundtrack. I’m not gonna argue if somebody says, “Well, that’s a Broadway thing and there’s no blowing on that, and there’s no . . .” You know what I mean? “Yeah, and? What’s your point?” I’m not gonna go see a John Wayne movie and be bummed because there were no spaceships in it, you know. You get what you get from something, if you’re open enough. But that record, Down Here in the Ground and the vibe of Herbie Hancock—I mean, his playing on that is just so . . . the way he plays to support Wes. It’s crazy. And Ron Carter. It’s just a beautiful-sounding record. They are limiting themselves to just songs, and there’s not a lot of blowing, but what a great-sounding record to just chill out and listen to songs and music. So I think there’s a place for it all.

It’s transporting.

To me, it is. I mean, it’s one of my favorite Wes records. I don’t go to it to look for, “Okay, Wes. I wanna see you shred your buns off and be blowing.” There are other records where he does that more, and it’s incredible. But it just has a vibe.

Do you prefer the softer side of Coltrane?

I kind of do, but that’s just my personal preference. I like the edgy Miles stuff, and I like the softer Kind of Blue Miles stuff too. I think “Naima” and some of that stuff—it seemed Coltrane played on the edge, tonality wise. It was almost like he purposely played a little sharp or something, which is really cool on some of the more hard stuff. It’s still great. But it wouldn’t be my go-to as much as more of the lyric stuff, I guess.

Are there parts of the Hendrix catalog you prefer over others?

Oh, absolutely. People don’t ask me about that and I don’t even bring it up, but I’m not a real fan of, like, releasing 160 records on Jimi Hendrix—“Oh, here he is in his house, playing the E chord.” I don’t think he would have wanted that. But he’s become such a commodity that there’s endless records that get released on him. And, you know, there is some stuff in there—recently maybe they’ve been trying harder to dig—but there’s some pretty cool stuff. Like there was a recent record that had a take of the Bob Dylan tune “Like a Rolling Stone.” Have you heard it? It’s not the one from Monterey. It’s killer! It’s great. There are some gems, and there are some stuff that really warrant it, but I think that there’s a lot of stuff that just because it has the name Jimi Hendrix, they’re gonna put it out. And I think, ultimately, would Hendrix have wanted this out? And I think that’s why kids should really go and listen to the records that Hendrix made, and not just hear the aftermath recordings that he didn’t necessarily want.

I always come to Electric Ladyland, because that’s the one album he produced. That’s as close as we’re ever going to come to knowing his own concept of how his music should sound. For me, that’s the most complete picture of Hendrix in existence.

It really is. It’s amazing. I listened to that record recently because we did the Hendrix tour, and I had to learn some songs I didn’t know. And yeah, he did that in 1968 too—it’s unbelievable! It was really ahead of its time. Everything’s great on it. I like it all.

How far back do you go with guitar players? Are you familiar with Charlie Christian, Eddie Lang . . .

Eddie Lang. Yeah, I’ve heard him. I don’t listen to him regularly. But Charlie Christian, I have his recordings. I listen to him. Who’s the other guy—not Eddie Lang, but . . . Lonnie Johnson. Yeah. B. B. really liked him a lot. Roy Smeck was cool too. He was a great player, but he’s from more like the ’50s and ’60s, I guess. Those are the main ones. Robert Johnson, of course.

What appeals to you about Johnson?

He was just a great technician. I mean, he just really nailed it all. The singing and the playing was just scary. And he didn’t have a lot of guitarists to listen to for that kind of level of playing.

I once asked Eddie Van Halen how he became so good at such a young age. He said that he came home from school, sat on the edge of his bed, and played guitar until he went to sleep. He didn’t go to parties or socialize very often. Did you find it necessary to make sacrifices and get rid of distraction that got in the way of accomplishing your musical goals?

Yeah. And then there’s that trade-off. You’ve got to be sure that you still have your life with your family and your loved ones. So it is delicate balance. Yeah, what you’re saying is so true. That’s what I did too. I’d come home from school and that’s all I did. I just played and played and played and played and played. It is a discipline and you’ve got to sacrifice all these things to do it, but you have to find that sweet spot, whatever it is, with music—like, if we’re talking about music and guitars. You have to find that sweet spot that’s going to spark a passion and an excitement for you so that you want to make that sacrifice. A lot of people who go to guitar school are, “Okay, I’m gonna go to school and I’m gonna practice, practice.” And it’s like licking a stone. It works—you’ll get mileage out of that—but I can’t help but think maybe next week, maybe next month, ten years, you’re gonna quit or get disillusioned, because you’re just sitting there ehh—it’s like grinding a stone. I think that Eddie Van Halen did that, or you did that with literature and journalism, and I did that with guitar because we couldn’t wait. It’s like, “It’s 3:15! I don’t care about . . . I’m gonna go home and play. I love it! It’s great!” I remember my fingers bleeding. I didn’t like it, but I was like, “Oh, I’ve got to keep practicing!” I mean, I could hardly let them heal, because I loved it! I just loved it.

I was at the right place at the right time to develop a love for it. My parents loved music. My dad loved music more than anything in the world, so I wanted to be like my dad. When I was five years old, I’d look at him and he would just be crying and laughing because of music. And then I was lucky to be born at a time when the Beatles—there’s absolutely great music now—but there was a certain fire close to the original inception of rock and roll, where you have people like Clapton and Hendrix. It was all a new sound. It was an inspiration to last a lifetime. You’d hear it and just go, “My God!” You couldn’t wait to discover this and that. The guitar wasn’t a household appliance at the time. I sometimes notice at sound checks. When I was a kid, I’d be at sound check. If I had a cool lick, the whole place would turn around—the guys setting up the chairs would go, “Wow! What was that?” I could play the greatest lick in the world now when they’re putting the seats in the theater, and they’re not even gonna turn around, usually. They’ve heard it.

These things [points to guitar] sit in every kitchen in the world. You see it on the front of magazines when you’re flying on an airplane—you know, the Strat. The Hard Rock logo is a Les Paul. We’ve been completely saturated by it. So I think I was lucky. At the time, it was like it came from another planet. And people that really interpreted it well and played it well were just so rare. It was such an inspiration. It can still be found today, but you have to dig a little harder to find it amidst all the cacophony. Having that gift to have such a love and passion for it allowed me to want to do that, to make that sacrifice. I don’t know if I’d have made that sacrifice if I hadn’t have been so impassioned and so blown away with how much it excited me.

So I think what kids need to do, if they want to play an instrument, guitar, you’ve got to create a vision of where you want to be, and then figure out a way to remove the obstacles to make it happen, rather than go, “Well, I’ve got this way I do it.” You create that vision. And when you create that vision, you’ve got to create it in a way that the sound or the playing is the way you want to do it. Even if it seems totally out of balance and impossible, you just like dream it. “Oh, I can hear this sound, I can hear this part! If I could do that, that’d be great!” You start developing a passion for that vision you have.

Then you have the recipe and the fuel that’s going to make you want to make that sacrifice. Those four hours [snaps fingers] are gonna go like that as you practice, rather than, “Oh, God. It’s 3:00, I got another hour,” and you’re sitting there killing yourself because you’re studying music in some school and you’ve got to do this. You’ve got to figure out a way to streamline that with making it fun. And a lot of times that will mean a certain type of music or a certain thing, rather than trying to talk myself into “Oh, I don’t like Down Here on the Ground. I’ve got to just do this.” Me, personally, if I had done that and it was only about playing guitar and playing licks, I’d probably put it away and not play. But it is about songs, and sometimes the simpler songs make you feel good. You don’t want to take for granted or belittle the things that give you that excitement of the heart, you know, because that’s the fuel that will keep the discipline fun, and then you’ll want to do the discipline.

Are you still making breakthroughs? Do you have an agenda of what you’d like to accomplish with the instrument?

Yeah, I want to learn more about harmony and chord changes and being freer to play melodies and solos over chords. I think there’s a lot there that would open up things for me if I would get more well versed and freer with that. So I’ve been working on that a lot lately, trying to get that together.

Have you ever noticed that sometimes the first pass is the best? You can cut a solo eighteen times . . .

Oh, yeah. Absolutely. A lot of people have given me criticism over the years, like, “Oh, Eric, you’re better live. You do nice records, but they don’t have the vibe, they’re too polished, they’re too . . .” You know what I mean? “Oh, it sounds like you beat ’em to death.” And you know, I think there’s a little bit of truth in all criticism, whether it’s 98 percent or 1 percent. I went back and listened to some of my records and I’m kind of late to the party, but finally, at fifty-eight, I started hearing what they’re talking about. You listen to the old blues records or the Wes records or all the records we love—God, like the ’50s Ray Charles stuff? I mean, forget it. I started really listening a little closer to that, letting that issue be prominent, and I can’t even listen to some of my recordings now. It’s like, yeah, it sounds like I went in there with a lab coat and a scalpel.

This is post-Tones?

Yeah, yeah. I mean, there are songs that have been recorded a million times, and they’re great. There’s a couple of Hendrix tunes that were supposedly done over and over for edits, and they’re great. But I think as a general rule—like you were saying—that aspect of making music needs to be a big part of your headspace as you’re making music. It certainly is when you play live. So why throw it out the window when you’re not playing live? So I think if we all want to grow and we all want to go forward and get better at what we do, we have to take inventory of what it is about ourselves that we can do to make this better. Some people, they’re so live and spontaneous that they never tune their guitar. It’s completely out of tune and they’re horrible, you know. But with me, it’s the opposite. It’s like, “Wow. Take 1 percent of that criticism.” If I do want to get better—not better in the sense of faster, but if I want to learn to make deeper, more significant music—I need to take inventory of what I need to do. And I think what you say—you can’t put enough emphasis on that. You know, if you went to your wife and you’re teary-eyed and you say, “Honey, I just really love you. Okay. Wait—I’m gonna go out of the room, I’m gonna come back in, and I’m gonna do it again.” You still mean it, but it might not have the same thing as when you just said it in the moment as you spontaneously spoke. Why should it be different with what I play on the guitar or what somebody else does? It’s just living.

To really make your mark as a musician—if you’re lucky enough to do it—it seems that you have to make an inward journey and base your music on that which is uniquely you.

Yeah.

You could never play Van Halen better than Van Halen, you can never play Billy Gibbons better than Billy Gibbons, and the list goes on forever. I wonder about the wisdom of spending so much time learning to play “Cliffs of Dover” or “Electric Ladyland” or “Voodoo Child” versus turning that stuff off and pulling out what’s you.

Yeah. I think if it’s a stop on the way to somewhere, it’s good. I went through a period where I sounded so much like Eric Clapton people were just making fun of me. But it was okay as long as I didn’t stay there. I learned so much about the way to pick the string and the muting and setting the amp. I loved his playing, and I had to ingest the whole concept and vocabulary of how he did it. And by that, you get to the point where you say, “Oh, I get it. I see how he did that.” If you just do that, I think it’s a dead-end street. But you can use it as a learning tool to just keep going forward and then let it go. As essential as it is to digest your heroes so that you understand technically what they are doing, it’s more important, when the time is necessary, to let it go and be yourself. You have to do that. I don’t think you only have to do that as an individual in art. You have to do that with yourself. I need to let go of “Cliffs of Dover.” If I want to keep my career blossoming, I need to be big enough and brave enough to let go of that. I can play it the rest of my life, but as far as conceptually, musically, and artistically, I need to be big enough to drop this history that I think is Eric, and open the window to see what can happen.

It’s interesting you say that, because I remember when I toured with B. B. King. I think it was during a sound check, and I was so stoked I was playing with B. B. King. I was running through all these blues songs I play—I’m not a blues guitarist, but I can play a blues style. I grew up on it, and I can do it. But that’s not the point. Where’s your space that’s unique to the world, where you really shine? You could write like Shakespeare if you wanted or whoever, but it might not be Jas Obrecht. I remember B. B. brought me into his trailer and he said, “What are you doing?” I said, “Well, I’m just doing my thing.” He said, “Well, that’s great, but you need to be you.” When people ask me, “What’s the best advice a guitarist you admire gave you,” it was him. He said, “You know, just do what you do that’s unique to the world.”

CODA: In the years following our 2012 conversation, Eric Johnson has continued to release albums and tour extensively. Following his 2013 concert recording Europe Live, he collaborated with Mike Stern on Eclectic, and he then participated in the 2014 Experience Hendrix Tour, re-creating the music of his main guitar inspiration. As this book was going to press, Eric was finalizing EJ, his first all-acoustic album.