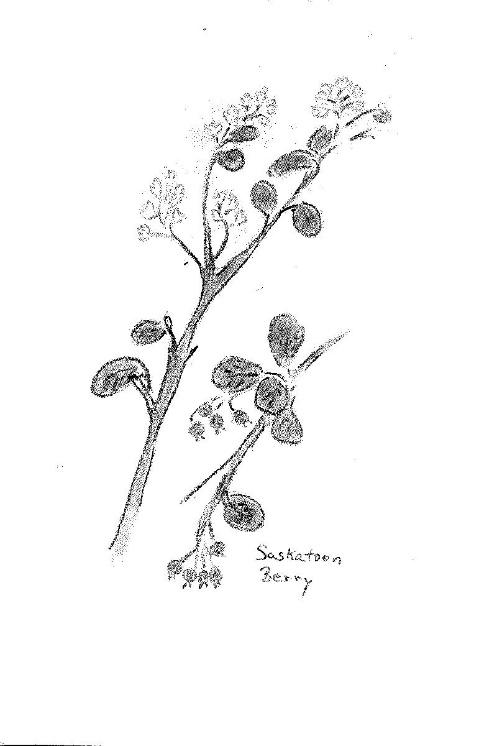

Saskatoon bush. Grows from 1-6 meters tall. Alternate ovate leaves with rounded tips. Smooth reddish-brown stem turns grey with age. Five-petal white flowers, blooms in late spring. Fruit red to purple round berries. Commonly grows in coulees and open woods. Fruit a valued food source. Gabriellas’ Prairie Notes

Remember the promise I made to myself? The one about putting questions and speculations concerning aboriginal history into the vault for a few days? Well, I tried, I really did. And for most of Monday, I succeeded. I let my mind fully inhabit the year 1945 as I wrote a piece based on Eric’s and his daughters’ memories, and attempted to picture him as he was then, at that time in his life.

Then, late in the evening, an email came from Madeline Hirondelle. She wanted to know what I had made of the files folder she had given me.

I responded that the information intrigued me, and I hoped to delve more deeply into her family’s story. I asked if she might have any first person accounts she would be willing to share with me. I mentioned my interviews with the Tollerud family, and how well it worked to use a composite of memories to build the story. Then I waited.

Ms. Hirondelle replied early the next morning. Against all odds, I must have made a favourable impression. She stated that if I was truly interested in pursuing research into a time that preceded settlement, I should come to visit her. At her home. This week, if possible. She explained that what she offered could not be considered part of the Centenarian Project, as the ancestor whose information she would share was her grandfather, who had died in the first third of the last century. Madeline had compiled family stories preserved by her mother, as well as genealogical material researched by her granddaughter. A multi-generational project. It still seemed unlikely that I would meet Madeline’s mother, who was indeed a Centenarian.

But. The good news was that Madeline the Teacher had overcome the misgivings of Madeline the Daughter, and, within limits, would share her family story if I first steeped myself in the early history.

That was exactly what I wanted to do. Learn about the time long before reservations and residential schools, when aboriginal people had more control over their day to day life, if not their destiny. I not only accepted Madeline’s prerequisite, I embraced it. The gap of lost years between Eric’s early memories and the Indigenous history of Jeff Reletter’s book might be partially filled by the material Madeline suggested.

I fired off a reply saying that, before the First of July weekend, I could take a few extra days off. I could come to see her on Thursday, if that suited her.

Then I renewed my resolution. Back into the vault I stored that wild mysterious period of history, out of sight and out of mind, and turned my attention to my day job. Exploring a different bit of history. That was surprisingly easy for me to do. I realized that in some strange way I had begun to identify with old Mr. Tollerud, to feel a proprietorial claim on his memories. I wondered if learning a personal Indigenous narrative might have the same effect?

Time would tell. For now, I would concentrate on recording as best I could Eric Tollerud’s century of life.

The fact was, I really liked the old guy.

I checked my notes from yesterday’s conversation with Jo and Carol. They’d talked more about their mom than their dad, and I felt I was getting a good sense of the character of their mother. It was obvious Eric was an aloof figure to his children, respected, looked up to, maybe feared. But it was plain that they and their siblings had adored their mom. A clearer picture of the woman who had married Eric, who had been his partner and lover for almost sixty years, was emerging.

Luxuries and modern conveniences had been lacking, but, from the memories these two old ladies shared, it was plain their childhood had been rich in other ways. Providing a happy and secure home had been Eric and Catherine’s major achievement.

I looked at my notes again and saw that their youngest child was born in February, 1950.

“Almost a whole month overdue,” Carol had exclaimed laughing and shaking her head, as though even now, the thought of her mother’s epic pregnancy amazed her.

Why shouldn’t that period be as memorable for this little family as the end of a war?

The winter had been brutal.

Catherine buckled galoshes over her shoes and pulled on Eric’s second-best winter jacket. It was warmer than her own coat, and the way the snow was slapping against their ice-shrouded windows, she felt in need of every bit of protection she could muster.

“I’m getting the wash off the clothesline before it blows into next week,” she told Carol. “Make sure that James or the girls don’t get too rambunctious and start running around the heater.”

The kids were kept home from school often this winter. It had been way too cold to send them out on horseback. Seeing they did not fall behind in reading and arithmetic had been added to her other jobs. Keep the house warm, keep from freezing. Keep the propane heater and the coal and wood stove burning but keep her babies and her house from being burned. Always busy, keeping her family fed, warm, clean and happy. Keep on keeping on.

That’s what we are, in winter. Keepers. Eric keeps the animals fed and watered, keeps the generator and windmill working, keeps the barbwire phone connected so we can call on a neighbour in emergency or loneliness or to share a funny story. We need to keep on going and wait for spring.

The frozen laundry did not flap in the wind. Instead, the shirts and towels swayed crazily like cardboard cutouts. Catherine carefully pried clothespins loose from the ice gluing them to the sheets and eased the frozen fabric from the line. Pants and shirts, she stacked on top of the sheets, carrying the frozen heap like cordwood back through the snowdrifts to the house. Her face felt bitten by the wind and her hands ached from the cold.

When did winter stop being fun? I used to love tobogganing, ice skating, singing in the sleigh as we drove across the fields to Grandma and Grandpa’s. Helping Mama bake cookies, Daddy reading to us by lamplight in the evening.

The door banged behind her and she heard the tinkle of the piano and children singing. Carol was playing one of the tunes Grandma Tollerud taught her. Catherine dropped her frozen bundle on the kitchen linoleum and peeled off her boots.

Jingle bells, jingle bells, jingle all the way. Kathy had a nice clear voice for a six-year-old, and Carol could even harmonize a little. Johanna joined in enthusiastically and tunelessly. James chanted Jingle jingle jingle and pounded on the only keys his pudgy fingers could reach.

Catherine laughed at them from the doorway to the living room. The girls turned and beamed at her, and little James ran to hug her as gleefully as if his mother had been gone for days instead of a few minutes.

“Oh, what beautiful music! Keep on playing, Carol. That is just what we need on a cold winter afternoon.”

She turned back to the kitchen, swinging James as he clung to her swollen middle. Only another six weeks until the baby is due. And if this winter continues as nasty as it’s begun, it would be crazy to start out for town with me in labour. I’ll have to stay in town at Gramma Flodens when my time is close.

She had been secretly looking forward to that brief respite from the unceasing labour of the house, her constant care for Eric and the kids. But suddenly she felt an overwhelming dread at the thought of leaving them, if only for a fortnight. How could they manage? Of course, Eric’s mother had offered to come for a few weeks. (Catherine winced at the thought of her mother-in-law examining the contents of her sewing-basket, filled with delicate yarn and patterns for baby sweaters and doll clothes instead of the wool socks, mittens and mending that Abigail would expect.) And they’d already arranged that cousin Lorraine would come to be her helper for as long as needed. Carol was old enough to help as well. But Catherine knew she would be missed by Eric and the children. Who would laugh with them, tell them stories, make their favourite chocolate pudding?

She set James firmly on his feet and bent over to give him a conspiratorial wink. “How about we make something special for supper? What do you think Daddy would like?”

“Pie! Let’s make him a pie, Mama!”

As the short December daylight faded, Eric stamped the snow from his boots and hung his coveralls and parka in the mud-room. The door to the kitchen was always kept closed in winter, to prevent heat from escaping, but the fragrance of apple pie filled the narrow, cold, room. As he opened the door happy voices spilled out with the warmth and light. He grinned and rubbed his chilled and calloused hands, then pumped water into the sink to wash up.

“We made you pie, Daddy!” shouted James from the high stool by the counter. His hands and face were sticky with sugar and cinnamon, and his heels beat a happy tattoo. “It’s our favourite!”

“M-mm! I could smell it clear to the barn!”

Carol was setting the table. She held up a plate of sliced cheddar. “And we even have cheese, Dad!”

Catherine smiled at him over the pot of potatoes she drained into a tin can. Potato water makes the most tender bread. Eric circled her bulging body with both arms, rubbed his face in her wavy hair, kissed her gently, lovingly.

Johanna and Kathy giggled.

“Apple pie without cheese is like a kiss without a squeeze.”

Ah yes, she did love Winter.