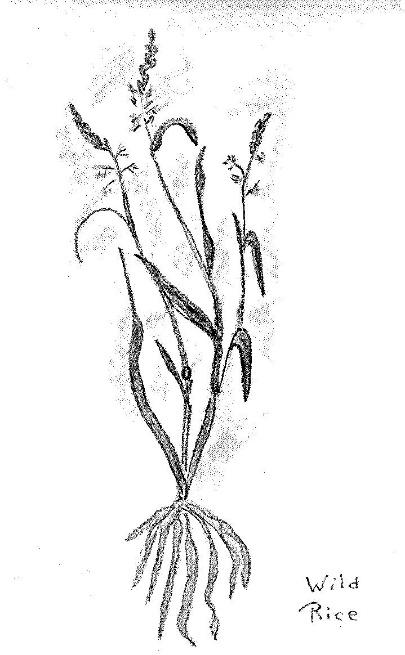

Indian Rice Grass. Stiff, leathery rolled blades. Diffuse open panicle with slender forked branches. Glumes papery and pointed. Likes sandy soils and rocky slopes. Fibrous roots. Good forage. Sensitive to overgrazing. Gabriellas’ Prairie Notes

I glanced at the thermometer in my car. 38*C. And it was only nine thirty in the morning.

I parked in the shade of the big elm tree on the street corner by the Pioneer Home, but even in the shade this heat was unbearable. I cranked the AC on full blast and opened the windows to let the heat escape. Not a breath of wind, nor a hint of rain. My head ached. No wonder old Mr. Tollerud wasn’t doing well today.

He was still in bed when I arrived a half hour ago. He’d forced a smile and reached for my hand when I leaned down to speak to him.

“Oh, I’m fine.” His voice sounded thin. “Never been one to enjoy hot weather, that’s all.”

Although it seemed at first a comfortable temperature inside the dim corridors of the Home, I soon realized the air was being recirculated. His room felt stale, stuffy, as though the oxygen had been sucked out. To be perfectly honest, it stank.

The care-home manager assured me they wouldn’t let the temperature build too high. But, she said, the air conditioning had to be carefully monitored to avoid chilling their elderly wards. It may have had something to do with budgetary constraints, too, I realized from the grumbling of the cleaning aides.

After adjusting his fan to provide what I hoped was a comfortable breeze, and helping him to a few sips of cold water, I realized he would be less miserable if he could just sleep the day away. I could do nothing but suffer through the heatwave with him. And if I had learned anything about the character of this old man, it was that Eric preferred to suffer in solitude.

Which is why I found myself shortly before 10 a.m. with a whole hot summer day ahead of me.

With no new material to work on, no family members available to pump for stories, I felt freed from any obligation to continue working on the Centenarian Project for that day. Besides, Diane had encouraged me to pursue the Metis story. I knew Annabelle’s notebooks weren’t something I could share with the Project Coordinator, at least not without Madeline’s permission, but I felt justified in labeling it ‘background research.’

I checked the bag I’d thrown in the back seat when I left Madeline’s. The binder filled with stories and research notes was still there. So was my beach bag. I’d heard Springwater Lake was a good place for a swim. What better time to test it out than a blazing hot Wednesday morning?

A few dozen teenagers and several families had already staked their claims to the prime spots. Picnic tables, lawn-chairs, and beach blankets lined the shoreline. But along a rock-strewn area between the main beach and a strip of sand jealously guarded by beachfront cabins, I found a smooth spot to spread my towel and a big flat boulder that could double as a table, both of them in a sunny spot that would be shaded by the time the sun passed its zenith in another hour or two. Perfect.

By the time I’d trekked back to the change-rooms on the main beach and traded my semi-casual professional garb for my hot-pink bikini, I was dripping with perspiration. The lake water felt chilly and wonderful and cleared away the last vestige of headache.

I opened the binder to the spot I had left off a few days ago. After reading and re-reading Madeline’s background and historical notes on this section, I turned to the photocopies of Annabelle’s handwritten notebooks.

Alternating between long swims in the cooling waters and relaxing on the hot sand, I probably looked like any other summertime visitor. But I doubt if any of the others on the beach that day had their heads firmly fixed in the 1800s.

Jean-Jacques slumped in his saddle and let the reins go slack. What does it matter where my horse takes me? I’ve seen all the world I care to see. Enough ugliness to haunt me the rest of my days.

He forced himself to straighten his aching back and blew a dust-cake from his nose. The scorching wind burned his face and glued his sweat-soaked shirt to his back. Even the weather is sick. Just a few more miles to the little Souris River. And the Fagnants.

Although he had never been to their home, and had only met Antoine Fagnant once, he had no doubt of his welcome. They were, after all, his people. Not family, not friends, nor neighbours, but his people all the same. And that had recently become most important to him. His people took care of their own.

For five years he had made his stubborn way among strangers. Now, heartsick and weary, he longed to go home. But no home awaited him, no one looked for news of him or would grieve for him, as he still grieved for Virginie and Pierre. That winter when he followed Maskepetoon on his peace mission, the sickness that had taken so many others, took them, too. Had the old chief cast some sort of spell on me, so I’d been willing to believe in him? All that foolish talk of living together as one tribe. Blackfoot and Cree united to keep their independence and freedom; country-born with their land-sense and newcomers from the east with their book-talk, both somehow working together; half-breed and Metis, Scot-Cree and French-Cree, all brothers. At the time it had seemed so sensible. So wise. So good.

Even when he returned in the spring to find Virginie and Pierre gone, their house abandoned and the only trace of their existence a stone cairn beneath which their bones lay mouldering, even in that overwhelming sadness, he didn’t regret having followed Maskepetoon. Only lately had he realized the foolishness of believing that talk of brotherhood. That, he realized now, was not the way the world worked.

For the first year after their death, Jean-Jacques wandered, never staying in one place long enough for the emptiness to catch up with him. Maybe he entertained some idea of earning wisdom like Maskepetoon’s, by travelling as he had. It was the first time Jean-Jacques had been so entirely separated from his own people. Sometimes he was friendless. Sometimes he went without food. But he was good with horses and a straight shot, willing to hire on with anyone who could pay. That was how he had joined company with a bunch of Texas cowboys.

Some of the cowboys had, like Jean-Jacques, chosen their wandering life. Others had been forced by the American Civil War to make their own way in a confusing world. Tough Texan soldiers returned home after the defeat of the Confederacy determined to rebuild. They discovered that, while they had been away, their equally tough longhorn cattle had continued to eat and breed on the open range.

It’s a fact, Jean-Jacques, they say Texas is plumb over-run with them danged long-horns. If’n you want to start your own herd, jus git yerself a brand and go throw a rope on some o’them unbranded mavericks, Jacob had told him when they met up on the trail. Great opportunity there, but risky too. Lots a fellers get their necks stretched fer bein’ a mite too for’rd.

New ranchers found other problems besides the danger of being taken for a rustler. The demand for beef in the south was almost nil. But for anyone who could get those rangy beasts moved north, the profit was ten times the pre-war price for beef on the hoof. Long-distance cattle drives were the key.

Jean-Jacques met his first Texas cowboy, a half-Black half-Cherokee known as Simon, outside a saloon in Deadwood. They shared a bottle and their histories that night, and next morning Jean-Jacques met the boss of Simon’s outfit, who seemed to like the look of the rangy Metis. Some of his trail drivers had elected to take their chances on one of the new Dakota spreads, or to prospect for gold in the Black Hills, instead of returning to Texas. The trail boss offered Jean-Jacques a job, but no wages for the trip to Texas beyond board and a bedroll. If the arrangement was mutually satisfactory, Jean-Jacques would get cowhand wages while working on the Texas ranch and on any subsequent cattle drives. His first wages would be paid in horses, since every trail-hand needed a string of half a dozen or more mounts.

Jean-Jacques, whose only possession at the time were one horse, an Indian-made saddle and not much more, merely nodded in agreement.

His position began as something between cookie’s helper and guard, but as his cow-sense and riding skills developed he was accepted as one of the boys. He and Simon moved from one outfit to another over the next few years, moving on whenever a boss proved too cantankerous or the work too tedious. They both preferred long-distance cattle drives to the monotony of routine ranch chores. Over the next few years they travelled dozens of old buffalo-worn trails from the Brazos to the Rockies or north from the panhandle through Indian Territory. Occasionally, they ended up back in the Dakotas. Cowboys and ranchers throughout the prairies recognised the tall, laconic Metis and the garrulous black cowboy as a pair worth their salt.

On Jean-Jacques’s first drive north, the two often volunteered to stand night-guard together. More than once they’d had to protect their horses from night-time raiders. Twice while traversing Nebraska they’d headed-off a stampede when the cattle were spooked by a thunderstorm or a prowling cougar. But often they whiled away the long hours practicing rope tricks or telling stories. Simon had an inexhaustible supply of macabre tales. His accounts of brutality he had seen or suffered at the hand of slave owners – “true as I live, I swear!” — were in jarring contrast to his mellifluous tone. But his voice warmed to melting point when he reminisced about his recruitment into the Union Army. “And that Major, he made an order that if’n any nigger was seen playin’ cards, that he had to do a reading lesson as well. ‘You’n gotta be worthy of being a free citizen,’ he’d say.” Simon chortled. “Trouble is, those white crackers in the other regiments had allus bin free, and they’s ignorant as a mule!”

He said less about the role he’d played as a soldier in the 62nd Colored Infantry. Jean-Jacques gathered that the black volunteers, last to be demobilized and left in Texas as occupying force, hated their role as much as they were hated by the Texans. Little wonder Simon simply walked away one spring morning and kept going until he snagged work as a cowpuncher. All that was believable.

But Jean-Jacques listened without comment to the other stories, the slave stories of beatings and brandings and rape. He decided they were exaggerations if not outright fabrications. Battles he could understand. He could fight when he had to. He had seen men die. But the casual brutality Simon described was too nightmarish to be credited in the clear light of day. They were experiences outside the boundaries of his known world.

* * *

Until one winter night by the Marias River.

Now, riding alone and friendless, tired and discouraged, his thoughts returned again and again to that night.

A hundred years later, the Blackfoot band whose ancestors were murdered would call that night the Marias Massacre. To Jean-Jacques, it was the death of a world he thought he knew.

And by rights, he shouldn’t even have been there. He and Simon had signed on with an outfit that arrived in the Dakota territories in late fall. The cattle delivered, they’d planned to while away the winter months trapping and wolf hunting, then head north in the spring to Jean-Jacques’s home country. But when the horse wrangler for their bunch, a small, wiry Peigan known sardonically as Moose, was thrown by a bronco and left by the boss, who had many urgent reasons for getting back to Texas, to recover or die in a flea-infested room above a Dead Wood saloon, pity or decency compelled Jean-Jacques and Simon to linger so their miserable companion did not at last go out of the world entirely alone. One night in January Jean-Jacques sat silently as Moose gasped out a last request. He asked Jean-Jacques to take his wages, what they could keep from the saloon keeper’s grasp, and buy supplies to take to his foster father, Chief Heavy Runner.

Trouble between Indians and whites festered into ugliness in the land that had once been called Indian Territory, and Jean-Jacques had, until now, managed to step aside from it, telling himself it wasn’t any of his business. But Moose reminded him keenly of the Blackfoot he had met while with Maskepetoon years earlier. Maybe it was his recollection of that fine old man that made him ashamed to say no to the dying man’s request. Maybe it was exactly the kind of burden Jean-Jacques would have been likely to place on his own friends if he had died while he still had family living. He promised Moose to do as he asked, and Simon agreed to go with him, albeit reluctantly.

“Y’all know that Sher’dan’s soldiers’d just as soon shoot a black man or half-breed as an Injun”

Early in the new year, they lowered Moose’s scrawny remains into the frozen earth and headed west to Montana Territory in search of Heavy Runner. They arrived at his large encampment along the Marias River just ahead of a snowfall. As Moose requested, his small hoard of cash had been converted to supplies desperately needed by the few hundred Peigan following Heavy Runner, whose band had been hit hard by smallpox the previous year. Most of the young men were away hunting, but Heavy Runner and the elders made Jean-Jacques and Simon welcome. The women hurried to prepare a feast with the unexpected windfall and children made excited and curious forays into the tipi to observe the two strangers. It was no doubt the best night of their miserable winter.

When the noise woke him, Jean-Jacques’s first thought the hunters must have returned. But excited shouts quickly changed to screams of terror. Jean-Jacques pulled on his boots and pushed open the tipi flap just as Heavy Runner emerged from the next lodge, waving the stars and stripes, and shouting in a confused mixture of Blackfoot and English, “Stop! Stop! Owl Child is not here! Why are you doing this?” The soldiers galloped towards them through the moonlight, shooting at random.

But the bullet that struck Heavy Runner was fired point blank.

Jean-Jacques dived back into the dark lodge and grabbed his gun just as the wall collapsed inward on the smouldering campfire. He stumbled out over Heavy Runner’s lifeless body and knelt for a moment, gasping as though he had run a mile. Blue-jacketed soldiers surged through the camp, some of them brandishing torches, knocking down lodges. From collapsed and burning winter lodges came the demented shrieks of trapped children. Dark bundles of rags writhed in pools of reddened snow. One of them seemed to be covered with Simon’s jacket. Jean-Jacques slid on his stomach through the snow and looked into Simon’s staring eyes. A horseman wheeled around a few feet away, and a harsh voice said, “Get out of here. Baker is crazy. I told him this was the wrong camp, but he’s ordered that we shoot everyone. Go, now!”

Somehow, he’d crawled or slid to the riverbank. A little girl clutching a toddler to her skinny chest hissed at him from a clump of bushes and he slid into the gully beside her. Together they huddled, both children wrapped shivering in his arms as the carnage gradually wound down, gunshots and shouts fading to sporadic echoes muffled by the still falling snow.

The next days were a blur of exhaustion and cold. Survival meant moving quickly, catching one of his horses, getting out of range of soldiers who might even yet be hunting down the wounded, getting across the medicine line to British territory. But every movement was an effort of will. His limbs were heavy, his mind sluggish. Besides horror at the slaughter and guilt at being the unwitting cause of Simon’s death, he suffered for the children. Circumstances had made them his burden. He had never known with such keenness the lightness and frailty of a small child, nor been more aware how quickly and silently one would succumb to the cold. He knew the smaller child would have died within hours if it had not been for the fierce care of the older girl. Marvelling, he held them before him on his horse, wrapped in a salvaged blanket against the piercing cold.

Eventually they overtook other survivors, a ragged band fleeing across the windswept snows towards a Blackfoot camp within British territory. They shared their few belongings, took their portion of the deer brought down by Jean-Jacques’s rifle, and plodded on day after day until the first line of tipis showed among the bare poplars lining a creek gully. They had reached the camp of Peigan chief Mountain Child. One of their number died on the trail, of hunger or sorrow or cold. But miraculously both children survived and were immediately taken in by a sombre-eyed woman whose own children had died in last year’s epidemic.

Jean-Jacques for the first time since the raid was able to feel something other than weariness. Finally, with leisure to sit and talk and piece together the bizarre chain of events, he realized the soldiers had been acting under the orders of a captain who, besides having a reputation as a drunkard, couldn’t tell one Indian from another. “The only good Indian is a dead Indian.” Jean-Jacques sat with the men around the chief’s fire, smoking and listening, feeling a kinship of indignation and fury, grief for the friend he had lost, sympathy for all the dozen survivors had lost. Nigger or Injun or half-breed. Give us an ugly name and it seems to give them license to kill us.

“What about the peace treaty your people had with the Cree?” Jean-Jacques asked Mountain Child, after it seemed the more current topics had been exhausted. “Last time I was in a Blackfoot camp was some years back, with Maskepetoon. He wanted to get the plains people to stick together and help each other. Any of you know old Bras Casse?”

There was silence for a space long enough for him to be aware of a stiffening and turning away by those on either side of him. Then the chief, a leather-faced man with tattooed cheeks, spoke.

“Monegubanou, as we called him many years ago, was a brave man.”

“Was?” questioned Jean-Jacques, striving to keep his voice steady and low, as was fitting in such a place.

“He was your friend, I see,” observed the chief. “He had many friends. Many enemies, too. For everyone who loved the idea of peace between the tribes, there were two who hated such talk. But Monegubanou never gave up his dream of making old enemies into friends.”

He coughed, passed the pipe on, and continued.

“With such happenings as you, and these from Heavy Runner’s band, tell of, it would have been well if old enemies had become friends and allies. But I am afraid the time for that is past.”

And Mountain Child told the story of the past springtime, when old Maskepetoon, with his sons and grandsons and a few others, walked for fifteen days through the greening prairie to come to the place where the Blackfoot, Peigan, and Blood bands were gathering in preparation for their first great hunt of the season. The elders and peace chiefs prepared to meet him as usual, with due decorum and honour. But some, none could say if it was one or two acting alone or if the warriors’ lodge had sanctioned it, prepared another welcome. As Maskepetoon entered the camp carrying his praying book, he was cut down by a Blood warrior known as Black Swan. Others drew knives to support Black Swan, while Maskepetoon’s sons and grandsons ran to defend him. Every Cree was murdered.

Mountain Child turned his somber eyes to Jean-Jacques.

“It grieves me to tell you this, my friend. Believe me, not all agreed with Black Swan’s actions, but it was too late to undo the harm. The spirit of war had returned. We had to prepare for battle with the Cree. And sickness came again that summer. The stinking sores the traders call the pox took one man of every two, a few women or children from every lodge. And when the sickness left us, raids and attacks continued between our people and the people without chiefs.”

* * *

Now, months later, Mountain Child’s words continued to echo through his brain. Jean-Jacques shook his aching head. He willed himself to focus on the present moment, feel the heat of the sun, smell the dry prairie grass. Think about meeting the Fagnants, hearing Michif voices

The spirit of war has returned. Will it never end?

He reined in his plodding horse. Like an itching scab, the same scenes drew his thoughts, whenever weariness or solitude overcame him. Nights were the worst. Screams and the smell of scorched flesh and the explosive shot that splattered Simon’s blood on the snow; or just as bad, the weary endless journey with the two suffering children in his arms, knowing that even if he got them to refuge, they would never know safety again. Sometimes in his dreams Maskepetoon rode with him for a time, and then disappeared without a word. Each day he awakened knowing all the people he held dear were dead, and that the world was filled with hatred, treachery and murder. The world is sick. The land, the people, the weather, all sick.

He forced himself to straighten his back. The prairie stretched in dun-coloured sameness under sunlight so intense it bleached colour from land and sky. Even though it was not yet the longest day of summer, sloughs had already dried up, the sparse remains of winter snow long since gone.

This treacherous heat, the wind blowing day after day, drying the grass. Nothing matters. The land is empty. The buffalo won’t come this year.

He rode on, knowing the little Mouse River had to be just beyond that next ridge, or the next after that. Every rise looked the same.

Then suddenly there it was, the Fagnant’s place, the sod-and-stone buildings almost lost in a broad sweep of grass and sage brush. Home of M’sieur Antoine Fagnant. Trader, hunter, farmer, sometime wagon-man. He lived from the land. Always ready with a story or a song. They’d met years before at Fort Pitt, but Jean-Jacques had never visited his home or met his family. It was old Jacob who had given him directions to this place and entrusted him with this package to be delivered to Antoine.

The burnt umber grass rippled right up to the buildings, wherever the ground had not been trampled bare. The house stood square and sturdy on its stone foundation. Surrounding it stood a cluster of storage sheds, lean-tos, corrals, wooden-wheeled carts, and one large wagon. At least a dozen horses grazed nearby, as well as several cattle. It seemed strange to him that he should have ridden all these hundreds of miles north and still find cattle.

But there was nothing strange about the dogs. They behaved as dogs do, a welcoming committee that could turn ugly if the stranger was not welcomed. They should have sensed his approach, but for the wind and heat dulling their senses. Now they made up for their neglect by jumping at his stirrups, barking at his horse’s heels.

A slight figure appeared from behind one of the buildings carrying a milking pail, her skirt billowing. She set her pail on a rough bench by the house and shielded her eyes from the sun as she watched Jean-Jacques ride into the yard. He swung down from the saddle.

Suddenly it came to him that this dark-eyed girl, braids whipping in the wind, might be frightened to see such a rough stranger approach. It seemed important that he explain himself to her. Of all the evils of recent months, the worst would be that this girl might turn from him in fear.

He doffed his hat and greeted her with the southern courtesy of a shy Texan cowboy.

“G’day, ma’am.”

The girl’s eyes widened in surprise. “Qu’est vous?”

Her high clear voice speaking an almost forgotten tongue cut through his layers of misery. He strode forward as he replied in her own language, explaining that he had brought a packet for Antoine Fagnant ... “son pere?”

“Oui,” she nodded, smiling, relieved to find they could understand one another.

“Pîhtikwî, tâwâw, âyapi nîtî, mîtso.”

She waved towards the house.

Eat. Rest. Talk. With people who knew what he knew, loved what he loved.