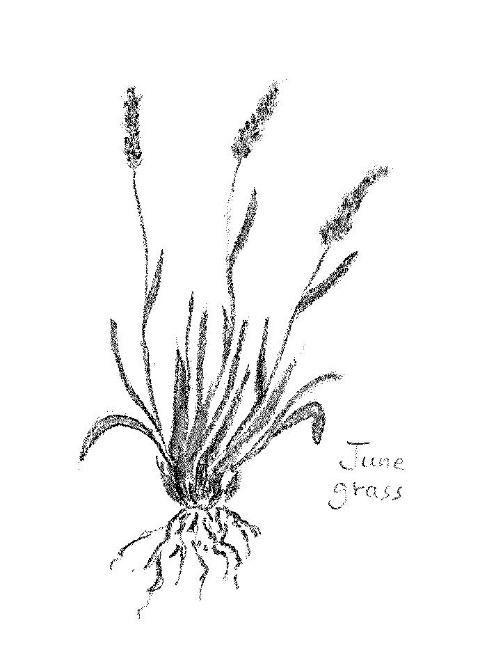

June grass. Bluish green blades, upper surface uniformly ridged. Spike-like pale green to purple panicles. Common throughout prairies. Fibrous roots. Good forage. Gabriellas’ Prairie Notes

Andy had tried to teach me how to recognize the crops we passed on our drive to Grasslands Park. That brief weekend, which may have been our last together, was now only a memory. But with a long country drive my present reality, I decided to put his teaching to good use. Although I had to admit I seldom agreed with his conclusions, or his line of reasoning, I’d found his facts, from ancient artifacts to current agricultural crops, were generally correct. Thanks to him, I could now tell a cereal crop from a pulse crop. However, to me, peas look like lentils, and that yellow mustard field might turn out to be canola. The little I’d learned served mainly to underscore the massive amount I did not know. That seemed a common theme in my recent experience.

With every insight I’d gained into this land and its history came the unsettling conviction that I had more to learn.

Jo’s invitation to meet her at her brother’s farm had come as a welcome distraction from my mental quandary.

I’d called her Sunday evening to ask about Eric. It seemed his condition was unchanged. He slept, took fluids, and occasionally stirred to semi-consciousness.

“But if you want to, you should come see him. He liked sharing his stories with you. And although he’s unresponsive, I think it would do him good just to hear your voice.”

“I want to show you some of the places Dad has told you about,” she continued. “The land where the soddie stood, where he grew up and where he and Mom raised my brothers and sisters and me. The hills of home. Everything will make more sense to you when you see that, don’t you think?”

I agreed, gratefully. Any story about Eric would be incomplete without at least a slight understanding of the specific place that had been home most of his life. In the past few weeks I had clambered over cliffs and coulees in the river breaks, jogged along the creek that runs through Swift Current, swum in a cold prairie lake, basked in the wilderness surrounding Madeline’s cabin, where aspen parkland melds into spruce forest. But this past weekend, I had met the great open grasslands just north of the US border.

The Grasslands. What can I say? The sheer immensity of land and sky pressed down on me. Something genuine and alive demanded my attention. This must have been what the country was like when Jean-Jacques was raising his family, or when Eric was a boy.

I found myself considering the sentient quality of landscapes, the almost mystical bond between people and the land. Subsistence required trusting the land for food, water and shelter. Human existence now and in the future must rely on the same resources. And I wondered, how can we humans survive if we are alienated from the land? And from each other?

“You cannot expect to have neighbours if you want to farm the whole country yourself.”

Eric Tollerud’s words echoed in my mind as I drove the lonesome country road out to the homestead where Eric lived as a small child, and where he returned to raise his own family. That farm was now owned by one of his sons. Half an hour or more from the nearest town, it was not an easy place to get to. Hilly pastureland flashed by my window, followed by a patchwork of green and yellow fields. Although most of the land was cultivated, inhabited farmsteads were rare. The country seemed empty.

I turned off the main road, as Jo had instructed, at the wooden sign “Tollerud Farm”, and followed a narrow gravel road for a few kilometers until, as I scooted over a long hill, the farm buildings behind long rows of trees came into view. This was the land Eric had described to me, the place that mattered most to him.

I turned at the lane and followed it to the ranch-style bungalow. Jo was waiting for me in her shiny blue pickup.

“James is at a cattlemen’s meeting and his wife’s at work. But they said to show you the farm. C’mon and hop in the truck with me.”

As she drove, Jo talked. “In the thirty years since James took over the farm, he’s turned most of the cultivated acres back to forage. Besides the grasslands that were part of the original homestead, and the sections of native prairie Dad used as pasture, he changed what was essentially a grain-farm into a ranch producing range-fed beef.”

As we bumped along over the dusty trail, I gazed out at green hills rolling to the horizon. James and his family didn’t have many neighbours. But they were surrounded by some beautiful natural landscapes.

“I think Dad was surprised when James started turning his wheat fields into pasture,” Jo continued. “He was bucking the trend to cash crops like canary seed and lentils and canola. Most farmers felt they had to maximize their investment, take risks to squeeze a few more dollars out of the land. James once described that process to me like this: ‘In the spring you take a hundred thousand dollars and spread it on your fields. Come fall, you go looking for it.’”

“Doesn’t sound like a very viable way of life,” I observed.

“Lots of farms went under in the nineteen-eighties and nineties,” agreed Jo. “Some agricultural pundits insisted we had to stop thinking about farming as a way of life and treat it as a business like any other business. Factory farms were the wave of the future. Well, you can imagine how much Dad liked that.”

I grinned and nodded.

Jo continued. “Dad took a pragmatic attitude about most things, in farming or in life. But that mindset, reducing everything to dollars and cents, that disturbed him. He used to tell our youngsters, his grandchildren and great-grandchildren, the few who chose to farm, that they needed to know their fields. He told them, ‘The best fertilizer for any land is the farmer’s footsteps.’”

She grinned as she gestured towards the grass-covered hills. “I doubt that James spends much time walking through these pastures. But I guarantee he knows every inch of them from horseback.”

We drove towards the hills, following a trail by the fence-line. Jo explained the cow-calf herd was on summer grazing near the river, land that had once been part of the Pradera Ranch. The pasture before us would remain empty until fall, when the cattle would be moved back home.

We stopped by a pond that at first glance seemed to be another of the naturally formed potholes or sloughs that dot uncultivated land. Jo pointed out the earthen dike planted with willows at the end of a draw.

“I don’t think this dam has ever been dry since Dad built it back in the thirties,” she said. I recognized a common thread in any conversation with the elder generation of this land. They were people who didn’t take water for granted.

Good water. Good land. I got out and climbed through the fence to the top of a small hill overlooking the dam. A sudden breeze brought the scent of sage and wild roses, contrasting clumps of pink and gray glowing on the opposite hillside. Orange and brown lichen covered the boulders cresting the hill, whose slopes maintained a natural crop of winterfat and blue grama and needle grass. Good winter grazing.

I once wondered if old Eric Tollerud valued the land for itself, or only for the riches it provided his family. In my recent reading about the wrongs done the Metis and Indigenous people of this land, it was tempting to dismiss all settlers as greedy, soul-less leeches who took without thanks and destroyed without thought. Looking over the acres of unbroken, never-damaged prairie, I knew Eric’s words weren’t meaningless platitudes. He had tried to pass on an appreciation of the land that, perhaps, could not be properly learned second-hand. It had to be lived, day by day, in all seasons, until the land became almost your mother or your child, and the creatures that shared it with you, your own brothers and sisters.

Jo sat down on one of the boulders. I did the same.

“Your dad really loves this land, doesn’t he,” I remarked.

“Yes. And everything about it.” Jo smiled. “Let me tell you a little story. A dozen or more years back, Dad had just moved to the senior’s home in Hillview ...”

Eric slumped in the passenger’s seat, frowning. It was only a year since he agreed to give up his driver’s licence and sell his car, about the same time he’d agreed to move into the Retirement Centre in town.

The past six years had been lonely. Ever since Catherine was struck down by a massive stroke. He’d sat by her bed day after day, holding her hand, talking to her, hoping for one more flicker of awareness. And when she finally slipped away, he had been at home, asleep.

For the first time in his life he became mired in depression, empty of purpose. It sometimes felt as though he himself must have died with Catherine. Just as the farm was his link with the land, Catherine had been his connection with their children and grandchildren. Both were as necessary to his existence as breathing.

With Catherine gone and the farm James’, those connections could no longer be taken for granted. One afternoon he took the Co-op calendar and, using a birthday book Catherine had kept, carefully marked in all the family’s birthdays. After that he never missed calling to wish each one a happy birthday. Those phone calls led to others, and his grandchildren’s affection, formerly so entwined with their love for Catherine, anchored on him.

But how to maintain a connection with the land? Until this past year, it had been his habit to drive the country roads for miles around. He remembered who farmed every acre, kept track of the rainfall and estimated the hay-crop of every slough bottom in the municipality.

Now that he had to rely on someone else to take him wherever he wanted to go, that was impossible.

This fine spring day, Jo arrived at the Retirement Home just after lunch and suggested a drive in the country to check on the progress of seeding and to look over the spring calves.

“I’ll be your chauffeur. You just tell me where to go.”

“Let’s drive to the farm. Check the crops. And the calves.”

Massive fields greening with young crops drifted by on each side of the road, monotonous in their sameness. Eric shifted in his seat, turned towards Jo and spoke again in a voice that sounded crabby, almost petulant. “How can a farmer know his land when he’s cultivating half the country?”

He waved at the baby canola leaves poking up through the dirt in the field on their right.

“Look at that, not a weed in sight, a nice even crop, but it costs a fortune to grow. First, you need to buy the seed, which only gives you the right to grow it one season, you can’t save any from your own crop to grow next year. And then you gotta buy the right fertilizer to force it to grow and herbicides to kill the volunteer wheat, but not your canola crop. And with all the land they farm, they haven’t time to get off of their tractors.”

A pickup truck pulled out around them and passed with a friendly wave from the driver. Jo returned the wave, asking “Wasn’t that the Floden boy, Dad?”

“Mmhm. Harold’s grandson. Took over the old place two years ago. Heard a real estate agent was out there last winter to see him, offering a good price. Didn’t say who the buyer was, but there’s been an Alberta land agent sniffing around. He told her he wasn’t interested in selling right now.”

They were moving along the road at less than 30 mph, the maximum speed, according to Eric, for crop-watching, but now he spoke sharply. “Slow down!”

Jo complied, asking “What is it, Dad?”

“Stop!” he ordered, excitement in his voice. “Back up!”

He pointed to an object a short distance off the road, just visible in the stubble field. “Look at that. Is it one of those little owls? I haven’t seen one in years!”

“A burrowing owl? I’ve never seen one in the wild.”

Jo pulled off the road and got out. She scrambled through the ditch and walked into the field, returned with the object in her hand. “Just a beer can.”

Eric snorted, and reverted to studying the fields in silence as they drove the remaining miles out to the farm. He looked towards the hills and remembered the sweetness of all the springs he had seen.

“Used to be, I’d see those little owls popping up every now and then out in the pasture.”

“Well, that’s probably why we don’t see many of them anymore, Dad. There isn’t much of that original pasture left. With all the land being worked every year, there are only a few places left where a burrowing owl can find a burrow.”

“Everything is changing, it seems,” he said. “Do you know, I haven’t even heard a meadowlark this spring. Wonder if it’s my ears.”

“I haven’t heard many either. It seems there aren’t as many around as there used to be,” Jo agreed. “I brought a tape recording of birdsongs to school one day and asked my grade threes to identify them. Most of the kids could pick out the sound of a crow, but not one of them knew what a meadowlark sounded like. That was my favourite bird when I was a kid.”

“They need grassland for their nests, too.” His memory went back to a sunny morning long ago and a small boy crawling through the grass. A wave of sadness washed over him. What was the use of all this fancy machinery and smart farming methods if the end result was a world without meadowlark songs?

Jo drove past the farmyard. “They’ll all be at work now, no point in stopping at the house.”

The road became a trail that followed the fence-line to the pasture below the hills. Years ago, Eric recalled, it had been made by his riding horse and the horse-drawn hay wagon. Now the trail was marked by the boys’ quads and their pickup trucks. But the purpose was the same. To check on the cattle, see the condition of the pasture, make sure their fence was intact.

A group of white-faced cows grazed along the fence-line beside the dam. The willows gleamed golden-green with new leaves. I planted those willows over fifty years ago. And we built that dam a few years before that.

“Stop over there.” He pointed to a low hill overlooking the dam. From there, they had a good view of the cattle and the big hills, the western hills that had always meant home to him. Jo lowered her window and he did the same. She reached into the back seat for the thermos and poured them each a cup of coffee, then opened a tin of cookies.

The calves frolicked around their mothers. Eric counted them, noting how much the herd had increased. Calving season was over for another year. A few of the older calves came up to the fence near the car and stared at them with serious brown eyes. A cool breeze carried the scent of wolf willow. The hills sprawled in the sunshine, light and shadow accentuating their sinuous curves, like huge prehistoric beasts warming themselves.

“Those hills haven’t changed much since the first time I saw them, nearly ninety years ago,” he remarked. “Seems funny, with all the changes to the country, they should stay the same.”

“Did you hear that, Dad?” Jo straightened up suddenly and looked out the side window. “A meadowlark! Singing right over there, on that fencepost. Can you hear him?”

“Yes, I hear him,” lied Eric. He smiled.