2

THE ISLE IS FULL OF NOISES

The Meaning of the British Invasion

THERE WAS an American daylight in the 1950s, a mundane light that penetrated everywhere, that drove the dark out of every hollow, the dew out of the morning—a perpetual noon. On the mornings when there was a mist, unhappy housewives stood in their kitchen doors for a moment to watch. When everything is bright and dry, mist is precious.

The suburbs stretched for treeless miles in the blank and obvious sunlight. America had learned from the war that it was the dryness and the obvious light that would keep us safe from the mad black rot of old Europe. History was the infection that the light was supposed to kill. From “the dark backward and abysm of time” the dark was deleted and the abyss flattened. The Civil War was seen as some kind of scrimmage that had gotten out of hand, and surely both sides were good Americans who had bravely fought for what they thought was right. Even the pit of slavery was flattened: we were not allowed to see how deep the darkness had gone. Dealey Plaza on November 22, 1963, was the zenith of this mundane light. You can see that pitiless glare on the presidential limousine in the Zapruder film.*1

It was the light that gleamed on gangsters’ silk suits, the desert light of Las Vegas, but the gangster glare was seeping into the remaining green places across the whole country. No matter what the film stock, every picture that was taken turned out to be black and white, or worse, a gray that was no color at all, with the faces washed featureless by the flash. To enforce the mediocre light, to excise any but the most barren stories, little boys with crew cuts and plastic guns were invited to plywood Western towns where the frontier had been. Norman Mailer saw “the evolution of a mass man . . . without a sense of past, present or future.”1

Indeed, what was missing was a sense of the past, of what the past does for the present. (This has changed in the half century since then—today all kinds of new histories exist, histories of popular music, of utopian communities, of sex, of slave resistance, of the occult, of organized crime. Many crucial untold stories are beginning to be told.) Communication with the past always has the potential of allowing some destabilizing energies into the present. The past may be denied, but it is never dead; it is a spirit world that lives alongside of us that we can see or not see, admit into life or not. It is the unconscious of a people. The past is where stories come from—stories are a relationship between the present and the past. Culture is a relationship with the past. Memory and meaning are almost the same thing. The first act of conquerors is to destroy the traces of the conquered people’s past, to deny them a history, because the past is what enables us to judge and challenge the present. The present is uninflected; the past is the dimension of depth in life. Without it, life is a membrane or surface only.

But that membrane began to be punctured in some places in the 1950s, and where it was you could often find African American music. One breakthrough came with the stirring of the modern Civil Rights Movement, sustained by the gospel-music liturgy of the black church. Then there was the rise of a new American bohemian-ism, the “Beat” culture, to a large extent inspired by the message its adherents heard in jazz. And there was the rock-and-roll boom of the middle and late fifties, as millions of young Americans began to respond to rhythm and blues and other gospel-derived forms of black dance music.

There was a thin current of dread in the postwar American consensus, some sense that the narrative that supported it might not be perfectly stable. There was a muffled awareness of other forces—from overseas, from the past, from some curtained-off chamber in the mind, maybe even arriving in flying saucers—whose movements could sometimes be felt, that were not accounted for in the narrative.

Rock and roll when first encountered seemed to represent two fears: a fear of the future and a fear of the past. There was a fear that the American ease and prosperity would lead to some novel style of decadence, so rock and roll was felt as something hurtling at us from the future. The noises and the dances seemed outlandish when first encountered by white adults in the fifties. In the eternal American present it could only be experienced as a crazy innovation. And in some ways it was. There could be heard a gratuitous new extremity in the shout of rock and roll, in the hysteria of Little Richard or the bodily abandon of Elvis, that seemed somehow of a piece with radical ideas in the arts that were filtered to the middle class through the Luce publishing empire, through Time and Life magazines. Then it felt crude in its blatant appeal to the hips, an appeal from a sordid low-down world that many suburbanites thought they had left behind in the city, a sensibility from the margins that was suddenly for some reason asserting itself in the most impudent way. So rock and roll was coming from ahead or behind, but either way it made the membrane of the present feel a little less substantial.

But the edge of rock and roll was blunted by the time the fifties ended. Rockers like Elvis Presley were not really interested in translating their rebellion into an ideology. Elvis came back from a stint in the army and proceeded to make junk movie after junk movie that seemed to endorse the consensus. Scandal, addiction, bad luck, bad judgment, and in some cases counterattack from the vested interests of the consensus, wore down many of the fifties rock-and-roll heroes. In the next few years there would be some great R & B–based pop music made, but for the time being the threat was in abeyance. The consensus found it could meet the music halfway, and the music met the consensus halfway. It seemed like the new teenage culture could be absorbed into a revised present; the teenagers could be turned from potential rebels into new kinds of consumers.

But another thing had happened. As an aftereffect of rock and roll bursting upon America, a burning piece of shrapnel shot across the Atlantic and lodged in Britain.

For all the cultural ties between the United States and Great Britain, the feel of life in the UK could not have been more different in the postwar era. The American powerhouse was manufacturing the present. Britain had been a powerhouse, had been for a century or two the engine of the modern world. All its ancient and riotous pedigree had been summoned to meet the menace of Nazi Germany, and it had survived and prevailed, but it had been stunned by the blow it had taken. It was as if Britain had had to expend the best of itself to stand against Germany: the pluck of its working people, the flair of its aristocrats, the eccentricity of its artists, the style of its adventurers. These qualities had been the admiration of the world, but in part they had been sustained by the exploitation of colonized peoples and a heedless system of class oppression at home.

The war had purged Britain of its glamour. Mystique and mystery had been consumed in the fight for survival. The culture of its aristocracy had been boiled down to a residue of stupid and stubborn privilege. A century and a half of ruthless industrial exploitation was repaid by the immiseration of millions. When Britons looked around after the war they saw a society that seemed to have frozen sometime in the 1930s. A quality of shabby smoke-stained squalor clung to everything, evident in the pictures from that time. The small, overheated rooms in the soot-colored brick row houses in the old industrial towns held a hundred-year fug. Britons emerged from the war like creatures who had been too long indoors, blinking in the light of a world they had fallen out of step with. The old flashing stories of the island race that had sustained them in the war seemed abruptly irrelevant to the demands of the present. Still, on the horizon behind the exhausted towns were the hills and streams and the dark rolling sky.

The blowback from the empire had more than one effect. On the surface, empire may have made many of the British blustering and racist, but on the imaginative level, it made some of them cosmopolitan and strange. There was a dream life or unconscious of empire, and Egypt and India and “heart-beguiling Araby” possessed the imaginations of Britons. A secret desire for the exotic and wild was implanted. At the zenith of the empire, some Britons had heard Isis or Krishna calling. By 1957 they were beginning to hear Little Richard. Through the great imperial ports like Liverpool, Britain’s merchant seamen brought the shout to England, in the form of 45 rpm rock-and-roll records from America.

Europe had been processing African American music for some time, at least since La Revue Nègre opened in Paris in the 1920s, and it had been picked up by European bohemians and fed into the culture-producing machine. As the late Roman Empire had once processed Semitic cults into world religions, the declining British Empire would now create a preposterous hybrid of fancy-dress bohemianism and African American Pentecostalism that would serve as the foundation for a pan-global culture based on pop music.

But in the early sixties, conquering the world inevitably meant going by way of the United States. In another transatlantic twist of history, the new British rock and roll would find there a generation strangely prepared for it.

American imaginative life in the 1950s was not uninflected. It was possible to find folds and gullies where pockets of subversive mystery held on that were not necessarily visible from a distance. Significant mysteries often hid in things held to be of no great moment, like children’s bedtime stories.

As a generation of American children laid their heads on their pillows in the 1950s, their mothers and fathers read them to sleep with stories, a large number of which came from Britain. Not Britain as it currently existed, or even as it had once existed, but a visionary Britain.

In Britain, its present bleakness notwithstanding, the landscape had for thousands of years been sown with stories. In that way it was a very different imaginative environment than the New World. The external landscape of a place and the internal landscape, the consciousness or the imagination of the people who inhabit the place, are related to each other. In the United States you can drive for hours and not necessarily see very much. In Britain, every cranny of the land looks like an illustration from a curious story, whereas the spectacular things in the American landscape—the Grand Canyon, Yosemite, the Rockies—in their huge sublimity repel human-scale narratives. It was similar in the inner life of the two places. The imagination of white civilization in America hadn’t had time to fold in on itself, to create grottoes and hollows of the mind, sedimentary layers of memory and tradition. The imagination of Britain is full of half-lit places and half-visible paths worn by centuries of wandering feet.

There are two histories in Britain (as perhaps there are in every place). Britain has a mundane history and a magical or imaginative history, but the relationship between them is complex; they are not always cleanly separated. The frontier between history and story is not policed as vigilantly as an American—or for that matter a Frenchman—might expect. C. S. Lewis called this semisecret Britain Logres, and Peter Ackroyd calls it Albion. The Welsh called it Claes Myrddin, “Merlin’s Enclosure.” You can trace it from the Iron Age on down. Its patron and founder is Arthur, king of the Britons. Its evangelist is William Blake. Its ritual is the mass of the Holy Grail. Its holy days are the twelve days of Christmas. It is not actually passed along by secret societies, rites, and passwords—those are metaphors for how a tradition like this survives—but each generation in Britain is reinitiated into their version of it. Like the tradition of the Invisible Institution in America, it stands apart from British history in order to comment, judge, parody, and sometimes contest it. The narrative has occasionally been co-opted by history, as it was, for instance, to legitimize the Stuart monarchy.

In the mid-twentieth century, its most powerful recent expression had been in works from the golden age of English children’s literature, from the late-Victorian era almost up to World War II. All the great old stories of Britain—of Arthur and Robin Hood and the fairy world, and the witches and the ghosts—became children’s stories during that time. They hadn’t begun as stories for children, but by the turn of the twentieth century it was only certain odd British adults—ones who wanted to write stories for children—that were still interested in the magical history.

These stories became popular across the Anglophone world, and they had a profound effect on the imagination of the United States, such that in a certain sense in America the world of childhood was an English world. The work of Olive Beaupré Miller is an example of how this happened. Miller was an American-born, American-educated woman living in a suburb of Chicago, but her vision of childhood was deeply rooted in British lore and literature. Miller published the first volume of her My Book House anthologies of literature for children in 1919. Volumes in the series had titles like In the Nursery, Through Fairy Halls, From the Tower Window, Over the Hills, The Magic Garden, and In Shining Armor. Miller’s idea of the heritage of childhood hovered over the mid-Atlantic, the images and stories in My Book House almost all European and specifically British in origin, the sources in English nursery rhymes and folktales, Shakespeare and Robert Louis Stevenson. An all-female sales force sold subscriptions to the set door-to-door, and the My Book House series became an immediate success and remained in print through the 1970s. For millions of middle-class American children in the 1930s through 1950s, these were the stories by which they learned to read.

Then there was Howard Pyle of Wilmington, Delaware, with his Merry Adventures of Robin Hood (still in print) and four-volume King Arthur series, whose illustrations created an English Middle Ages (and later a buccaneering Spanish Main) that Hollywood still perpetuates.

American children knew Victorian London from A Christmas Carol, Edinburgh from Robert Louis Stevenson; they haunted Hyde Park with Peter Pan, the Lake District with Peter Rabbit, Oxfordshire with Alice, the Home Counties and Thameside in The Wind in the Willows and The House at Pooh Corner, Yorkshire in The Secret Garden. With the Just So Stories they traveled to the high and far-off times, they went to Narnia with C. S. Lewis, and to the land where the jumblies live with Edward Lear. When they were old enough to read for themselves they were given Sherlock Holmes or Kidnapped or The Scottish Chiefs (and elegant horrors, Dr. Jekyll, and the troops of British ghosts). When they went to the movies they found Errol Flynn and Basil Rathbone, Dracula and Captain Blood, the flamboyance of pirates and the diffident dash of imperial swashbucklers. American children heard so much about this imaginary Britain that it was sometimes hard for them to tell as they grew up what were their real childhood memories and what came out of those stories. Without knowing it, their parents had initiated them into the British secret history.

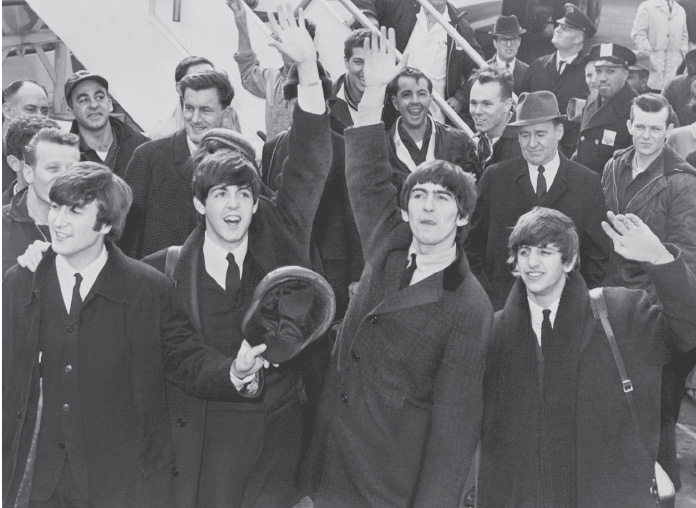

And then in 1963, when these children were not so far past their bedtime stories, came the Beatles. And yes, the Beatles were as shockingly novel as everyone says; but on the other hand, the American adolescents who responded to them already had a kind of interpretive framework with which to understand them. They instinctively understood that these young men, with their fascinating accents, their schoolboy hair, their air of cheeky panache, their dashing clothes, were not of the colorless present, but creatures of story. They were envoys from the secret history.

One thing that was striking about the British musicians was that they were clearly boys, though they were of an age when young men in America were already men and looked the way they were going to look until they died. The Beatles appropriated the visual style of English public schoolboys but unhitched the style from its connection to class. They were a version of the protagonists of English children’s stories, the ones who discovered phoenix eggs and secret gardens. The implicit idea of the Beatles was that childhood—or certain things about childhood—could become a way of life. And this, after all, was the spiritual point of English children’s stories, made again and again—that the child was father to the man, that the ability to see as a child was the saving element in the adult. The stories were about looking to aspects of childhood as a model for life, about turning the world upside down so that the hugely more powerful (and hugely more boring) adult world would acknowledge, in the end, the spiritual superiority of the child. It’s a vision that goes back to the Romantic poets and before them to the Gospels. The story of the sixties is the story of this upending of society, of the weak moving into positions of cultural power and influence, where they would judge the formerly powerful.

Fig. 2.1. The Beatles arrive at John F. Kennedy International Airport, February 1964

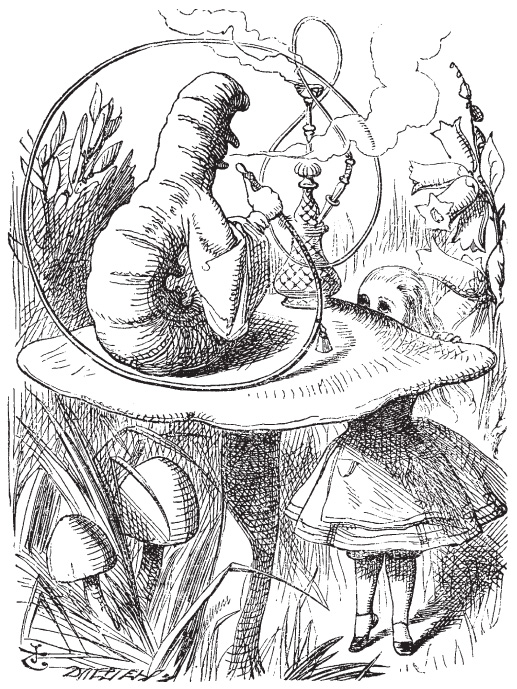

Group after group of these lost boys washed up on American shores, and they came with a sensibility that was an organic part of their style, with a sense of humor so quick, understated, and of lapidary absurdity that it seemed to come from Lewis Carroll by way of Oscar Wilde. A girl who had read or who had been read Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland or Edward Lear’s Book of Nonsense had the hermeneutic key to John Lennon. (“I used to live Alice,” Lennon said.) This would only become clearer as the decade went on and the Beatles (and many other English pop musicians) felt freer to explicitly invoke memories from their own childhoods.

The seeds of a counterculture lay in the sense that the Beatles and other English groups gave of not just being random novelties, but of representing an already existing sensibility; they suggested that there was a culture behind them that had produced them. And, while this culture might be hard to locate or define for Americans, it seemed clearly to have something to do with the stream into which the young American Beatles fans had been initiated as children. The British rockers were at the same time utterly new and recognizable, novel but evocative. The only preparation the American fans had for the Beatles and the English bands was in an imaginary world, and they could sense that the Beatles had approached along a line that ran close by that world. The Beatles suggested to their fans the very good news that there were places where imagination and the real world intersected.

And while it is true that if these Americans could have been dropped into the middle of a contemporary English city, they would probably not have recognized it as being that place, neither were they mistaken. Their childhood exposure to a British mystery could in fact be followed back to a source, a real underground current that really did run through British life. As the sixties progressed, the idea grew that that the British “already knew” about altered states of consciousness, that they had been exploring them for centuries as part of their cultural patrimony. They were seen as old hands on the frontiers of consciousness, just as British adventurers and explorers always seemed to be unflappable guides to the world’s wild places.

Fig. 2.2. Alice meeting the Caterpillar from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (illustration by John Tenniel)

Timothy Leary said, “The English are the original hippies. They’ve been writing about (the psychedelic experience) for three hundred years. The English have seed style. The polished performance based on the rich racial myth: a hip DNA root structure that enables them instinctively to deal with the pulsing energies of our time—electronics and psychedelics.”2

The outbreak of British rock and roll was the seed of a resurgence in Britain, a modern embodiment of the old stories. The cultural ferment begun by the music pulled most of British life along with it, and all things British seemed to effortlessly find a place in a sixties pageant that felt very new and yet like it had always been implicitly there. The architecture came alive. The neo-Gothic fretwork of Parliament fit naturally as the backdrop for bands on their album covers.

It was as if the new hip culture was finding a frequency that had been broadcasting for centuries. As the decade went along this would only become more explicit, as Brian Jones took up residence in Christopher Robin’s house, Mick Jagger and Keith Richards installed themselves on the turf of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in Cheyne Walk, and the Beatles moved onto St. George’s Hill, where the Diggers had brought Heaven and Earth together. Glastonbury, King Arthur’s Isle of Avalon, became the site of music festivals, rock-and-roll bands retreated into the countryside to record in ancient manor houses or stone cottages, and thousands of young people became aware that they had been living in Middle Earth all along. Freed from the selection of events presented by history texts and schoolteachers, young Britons chose the stories they liked and fashioned or rediscovered an alternate narrative. This involvement with the past was not nostalgic or conservative. Rather, it was as if they had discovered a subversive treasure that had been buried in their island long ago waiting for the right generation to uncover it, like Stanley Kubrick’s monolith on the moon.

But of all the revenant British pasts that returned in the sixties, one era seemed especially close—the hinge of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, from the end of Victoria’s reign to the First World War, a strange dreaming time of fin de siècle whose vapors were only cleared by the shock of World War I. It was the era of the occult revival, of artistic revolt against bourgeois life and for the irrational, of the great English ghost story, and, as we’ve seen, the golden age of English children’s literature. Its revival in the sixties could be seen in the Edwardian shop names like I Was Lord Kitchener’s Valet in the fashions that one newspaper writer sniffed were those of “English homosexuals of the Mauve Decade” (indeed the dandy was seen again on the streets of London), and in the names of albums (Pink Floyd titled their first album The Piper at the Gates of Dawn after the most mystical chapter of The Wind in the Willows). As Ian MacDonald said, the “true subject of English psychedelia was neither love nor drugs, but nostalgia for the innocent vision of the child.”3

But if American children had been imaginatively prepared by literature for an influx of Britishness, there was also another kind of preparation happening in America. Since the Depression the American Left had been using music to help craft an alternative narrative to bourgeois and capitalist history. In the course of this effort they uncovered troves of songs from black America, poor and rural America, laboring America, immigrant America. The fifties and early sixties phase of this project has come to be remembered as the folk revival. In New York City and on college campuses, immediately before the arrival of the Beatles, young Americans were using music to fashion a usable past, to create a dimension of depth in the present where mystery and neglected histories might find roots. In 1963 the East Coast folkies weren’t much interested in rock and roll. They had no apparatus to detect significance in the arrival of these smiling English boys with matching suits and puppy-love lyrics. It seemed to have nothing to do with their project. But what they could not see, and that was indeed relevant to their cause, was that the Beatles and their cohort were tunneling into American reality from another direction, a tunnel that would ultimately link up with the folkies’ own to create the possibility of a new kind of bohemia, one with the potential to actually reorder society. Jim (later to be Roger) McGuinn, at the time a dedicated folkie, heard it coming. While it was not hard to hear black America in the Beatles music, McGuinn heard something besides: “All their chords were folk chords,” he said.

When the mode of the music changes, says Plato, the walls of the city will shake. Color and freshness blew in to the black-and-white American world any time you turned on the radio. The amplified return of gospel triumph put across with a bracing northern English drone, then cannily coated in pop sweetness, blew open the present, revealing unsuspected spaces. Anything might happen.

The adult world betrayed its secret understanding of the magnitude of the change by the contradiction in its response—this new English music was at the same time both meaningless silliness and a menace. They alternately reacted dismissively or hysterically, but the one way they would not react was to take it seriously.

But then there were the girls dancing in the basement of the suburban homes, and, yes, they were just having fun, and they were giddy, but they were also hearing something in the center of the sound. Down there in the basement below the living room where their parents sat watching the news and hearing the thump through the floor, downstairs in the center of the silliness and softness, in the trebly coil of sound from the compressed cardboard record players, the girls danced. As they danced and laughed, so far from seriousness, a part of them was in fact attending to the music perfectly seriously, and in that attention they began to feel what made the sound possible, to feel a way of being in the world that had been prepared for them somewhere else and some time before but that was all about finding a surprising option in each new moment. In the awareness of the girls a new kind of American underground was taking shape, not transmitted by alienated urban intellectuals but by the children of the bourgeois. The girls were the first to be attracted, but before long everyone would be attracted.

While their parents could only hear the novelty and the ephemerality, the girls could hear an offer of fellowship in a society that crossed time and geography. How it came to be and how it came to them was still a riddle. But they would set off from their parents’ houses to find the answer.