3

THE WESTERN RIM

Los Angeles, San Francisco, and the California Apocalypse

Know ye that at the right hand of the Indies there is an island called California, very close to that part of the Terrestrial Paradise, which was inhabited by black women without a single man among them, and they lived in the manner of Amazons. They were robust of body with strong passionate hearts and great virtue. The island itself is one of the wildest in the world on account of the bold and craggy rocks.

GARCI RODRÍGUEZ DE MONTALVO, THE ADVENTURES OF ESPLANDIÁN

Here from this mountain shore, headland beyond stormy headland

plunging like dolphins through the blue sea-smoke

Into pale sea—look west at the hill of water: it is half the planet:

this dome, this half-globe, this bulging

Eyeball of water, arched over to Asia,

Australia and white Antarctica: those are the eyelids that never close;

this is the staring unsleeping

Eye of the earth; and what it watches is not our wars.

ROBINSON JEFFERS, FROM “THE EYE”

CALIFORNIA, the ocean rim of North America, was the last stop for the great white horde of westward-roaming Indo-Europeans, whose restlessness makes half of history.

You stand on the boardwalk at Santa Monica, or on a bluff above the beach at Point Reyes Station, and you think, This is where it ended: the enormous trek westward that began when the tribes fragmented in bits and pieces off the top of the Indian subcontinent and started that strangely compulsive walk west, through western Asia, becoming the Scythian horse people; across the Balkans, seeping down into Greece, then down the Italian Peninsula; and the ones who lingered began Rome, with the creation of civilizations being almost an afterthought to the energy of this migration, and over centuries, millennia, they cover a swath of western Europe the size of a people, and they founded another civilization with Gothic heaven-thrusting spires and the sound of bells and the smell of burning pyres, and they come to the edge of the sea and mill about on the shore, till another spasm of wanderlust leaps the Channel and begins to fill Britain. And in another millennium or so that’s not enough, and because they cannot stand still they are compelled to face their greatest challenge: the “stormy moat” of the Atlantic. And they do it, they cross the ocean, they crush the indigenes (again), they claim and populate a continent vaster and much richer than the steppes of Asia where the trek began. And they work and kill, creating huge wealth, huge misery, and then they come to the end. On this shore, having gone to the farthest west, so far that they are now looking east, another ocean crossing will bring them back to where they began. Only this time, for a complex of reasons, they stop.

The western frontier, which had called them irresistibly for three or four thousand years, is finally closed. The eternal West, which had troubled their sleep and drawn out their best and worst, but always kept them moving, is no more. And Western man, out of India, by way of Anatolia and Macedon and Athens and Rome and Gaul and Albion and the United States of America, is forced to reflect. For the first time some of them begin to wonder, what have we come this way for? And so a change begins on the periphery. The great migration turns inward.

And the thought splashes back from the Pacific edge, washes back east through the continent behind them, through all their people, now settled, the questions that are forming in the west begin to unsettle the people again, this time for no migration you can trace on a map. They have arrived at the place where the story will be transformed, or reach its disastrous end.

In the dream life of these tribes, from the Kurgan steppe to Omaha, Nebraska, was the idea that in the West lay the earthly paradise, a place of undying bliss or incalculable riches, and this goad has pricked them into new migration and new conquest again and again. So when they finally come to the ultimate earthly west, the Pacific coast of the Americas, and there is no more west to give their restlessness a goal, they are on shaky ontological ground.

A question occurs to some of them—might they in fact finally be there? Having come in one sense to the end of history—of their history at least—have they come back around to myth again? Have they come to that place in the story when images from the deepest past are realized as present reality? Have they in fact achieved the goal of their endless striving, if they could only see it, achieved Tir na Nog, Avalon, the Hesperides, the Terrestrial Paradise, Hy Brasil, the Fortunate Isles? And if so, what would that mean exactly? What happens when history runs aground on myth?

The idea that paradise has been regained has been a theme of travelers’ tales about California from the start. And so the spiritual history of California is one of utopias, sects, and cults, new religious movements that declared the split between heaven and earth, myth and history, reconciled.

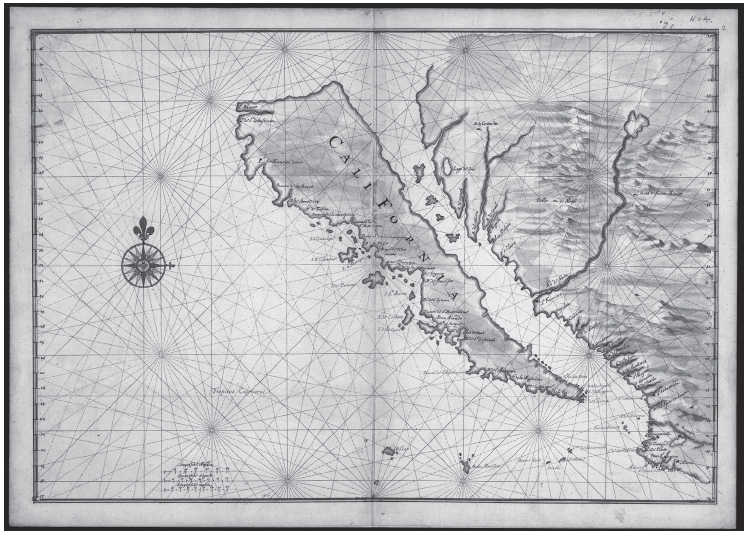

Fig. 3.1. Map of California as an island circa 1650

The unstable condition of the West Coast’s population has correlated since the 1920s with two measurable phenomena: (1) A much higher percentage of the West Coast’s population are unchurched or rarely attend public religious worship than is the case in other regions of the country, and (2) more new religious movements (NRMs) originate on the West Coast than in any other region.

PHILLIP CHARLES LUCAS, THE ODYSSEY OF A NEW RELIGION

Between 1850 and 1950 more utopian colonies were founded in California than any other state. Not untypical was the Fountain Grove Community of Santa Rosa. Thomas Lake Harris’s Brotherhood of the New Life had its origin in New York State, but led by the inner light to the “new Eden of the west,” Harris brought his followers to California in 1875. Members of the brotherhood practiced “a Divine Breath or Respiration which, when properly cultivated by man, would . . . lift him to the very threshold of heaven,” and believed in a bi-gendered God. The brotherhood, according to historian Robert V. Hine, was “the product of . . . a deep feeling for social reform, Christianity, spiritualism and Swedenborgianism, mixed . . . with later additions of Oriental mysticism and late nineteenth-century anti-monopoly socialism”1—a striking anticipation of later California utopias. Thomas Lake Harris, who was something of a poet, wrote that the community’s

. . . golden babes are born to sport

Where lift the waves of Mother-Glee

Borne through this vast Pacific Sea.2

In 1909 American advertising artist Harvey Spencer Lewis traveled to France in search of Rosicrucians. He found them, or a version of them, was initiated into the order in Toulouse, and given the mandate to establish an order in North America. Inevitably he went to California. Headquarters for the Ancient Mystical Order Rosae Crucis (AMORC) were established in San Jose in 1927. Members included Walt Disney and Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry. (Later AMORC scholars suggested that Rosicrucians first came to America in the area of Carmel-by-the-Sea with the Vizcaíno expedition of 1602.)

What is more certain than the arrival of those early Rosicrucians is the arrival in California of wise men from the east, like the Hindu guru Swami Prabhavananda who founded the Vedanta Society of Southern California in 1930. With its headquarters in Hollywood, the society became one of the most important centers for the spread of Eastern religious ideas throughout North America.

And then of course there were the film studios that developed an astounding proficiency at what had once been the occult art of evoking and giving life to images, potent images that would lodge themselves in the imaginative life of the people.

An important fact about pre-sixties alternative spirituality in California is that many of the practitioners were not necessarily what we would call bohemian. Many of them were not at all like Beats or proto-hippies, not necessarily visionary artists or political radicals, but middle-class professional people, people who—in the most rootless part of a rootless nation in love with the novel and innovative—saw these varied teachings as an adjunct to the new and improved American life that was being developed in the West. It was a strange but consistent offshoot of a mid-twentieth-century Americanism that imagined a sort of illuminated bourgeoisie who, as the nation raced ahead in technology and science, would concurrently apply these sciences of ecstasy toward a new degree of personal fulfillment. Aldous Huxley, brilliant scion of English intellectual aristocracy, looked out over the ages from his perch under the Hollywood sign and assembled his “perennial philosophy,” only to see it transformed into the sunny futurism of Esalen and the human-potential movement. Slowly, the leaven of the world’s esoteric traditions entered California life, in the guise almost of a new science, a practical resource for the demi-paradisiacal lifestyle that the American citizen had been half-taught to expect.

And so a stratum of American society on the West Coast was gradually unmoored from the rest (the occultists would say it began to vibrate at a higher rate). The old Protestant wisdom that life was a vale of tears, a hard row to hoe, seemed to lose some of its self-evident quality. There were perhaps not so many obstacles to joy or fulfillment in the human proposition as had once been commonly thought.

A generation grew, the children of parents who might have practiced yoga since the 1940s, or taken correspondence courses from the Rosicrucians, or heard Manly P. Hall lecture on the secret teachings of all ages, and they grew into a culture where the life of the young was starting to loom much larger, to take on a quality distinct from childhood on the one hand and adulthood on the other, exerting a greater cultural power and influence than it ever had before. That the interval between puberty and one’s early twenties was a distinct phase of life became clear in California first. California teen life would become the Platonic ideal of “youth culture”—everybody knew the California kids were way, way ahead, and all the teen scenes that sprang up around the world in response were lagging shadows. Teen life in California would become the laboratory for working out the implications of the new ease of life that people sought on the coast. There was nothing beyond them but the vast Pacific, the ocean of peace, a living metaphor for the un-mappable possibilities that seemed to be opening up.

By far the most potent means for transmitting the California youth culture’s message to the rest of the country’s young would be the music.

In 1964 a band called the Rivieras, made up of six friends from South Bend Central High School in Indiana, hit number five on the national charts with “California Sun,” a cover of a song first recorded by New Orleans singer Joe Jones in 1961.

Jones’s version was a jumping high-spirited dance number with a New Orleans roll. Jones’s California sounds like just one stop on an extremely agreeable ramble around the fifty states. But the Rivieras caught on to a one-way momentum that was starting to pull at the kids in South Bend, a gravitation to a new pole. For one thing the Rivieras didn’t leave the lyric alone. Here’s Jones’s first verse:

I’m gonna go back out on the coast

Where the California girls are really the most

They walk that walk

They talk that talk

They twist a-like this.

They shimmy

A-don’t you hear me

Yes, they’re out there having fun

In the warm California sun.

Here’s the Rivieras’:

Well, I’m goin’ out west where I belong

Where the days are short and the nights are long

Where they walk and I’ll walk

They twist and I’ll twist

They shimmy and I’ll shimmy

They fly and I’ll fly

Well they’re out there a’ havin’ fun

In that warm California sun.

Note that Jones has been there before—he’s returning to a remembered good time, like how Chicago keeps tugging Frank Sinatra’s sleeve. The Rivieras have never been, but they know that’s where they “belong.” The Rivieras have heard that somewhere out west there’s a place where the kids are having fun, and it’s somehow their place too, simply by virtue of being teenagers, and they’re determined to get there. That’s why, where Jones’s version jumps, the Rivieras’ version is all forward momentum, the organ and the guitar racing each other in the break to push the speedometer as high as they can make it go. A great force is pulling that Stingray westward out of South Bend.

Note too that Jones is just admiring the girls and the way they dance. The Rivieras, on the other hand, want so much to be a part of it that they pledge four times in a row that they can do all the dances the way the California kids do them. That’s the whole reason to go: to do them like they do.

The Rivieras turned Joe Jones’s New Orleans jump into surf music, a style that generated excitement by creating a danceable impression of the propulsion and mobility of riding the waves along the Southern California coast and later of the pleasure of cruising in customized cars, made available to teens by the general postwar prosperity along the coast. The Beach Boys, of course, were surf music’s most popular proponents, and by 1964 they had become masters of precise packets of hormone-fueled pop pleasure, full of delight in the new autonomy and sexual possibility that the surf and the hot rod bestowed on male adolescents. But in the next few years something else began to emerge from the Beach Boys’ romp. The high California sun, always implicitly at its apogee in a Beach Boys song, began to penetrate songwriter Brian Wilson’s music from other angles. In addition to the midday glare you could begin to feel the rosy gold of dawn or sunset, or the melancholy of late afternoon. The teenage swashbuckler of “I Get Around” (“The bad guys know us and they leave us alone”) turns into a guy who’s mostly worried about shielding his little sister from a broken heart.

On Shut Down Volume 2, ostensibly another album of hot-rod songs, you can hear the Beach Boys turn a corner. The album starts with “Fun, Fun, Fun,” a paean to the exciting notion of a girl winning the hot-rod race. But a couple of cuts later, Brian has left the strip and, alone in his room, is singing in an ethereal setting,

I have the warmth of the sun within me at night . . .

The California sun, the focus of Brian Wilson’s world, has become an interior sun. Before, the elements of the Southern California environment, the sun and sea and the streets, were adjuncts to, or instruments for, pleasure; now they begin to suggest inner states—poignance, longing, wonder. This interiorization of the golden glow deepens the affective power of the Beach Boys’ California. Wilson soon brings in Phil Spector’s studio musicians, the builders of the famous “wall of sound,” and uses them to give his songs rhapsodic color. By the time the Beach Boys come to the album Beach Boys Today in 1965, the teen energy of the Del Mar beaches and the cruising strips has been sublimated. The attitude has gone from the brag of “I Get Around” to inward-looking songs with titles like “She Knows Me Too Well,” “In the Back of My Mind,” and “Please Let Me Wonder.” And the celebratory songs took on new richness. When the Beach Boys reach the Technicolor chorus of “Do You Wanna Dance?” the invitation feels like a vast exhalation, a huge wall of breath, the sound of a people relaxing, as if, having reached the end of all striving, there was only one question worth asking: Will you join the dance?

In 1962 a California-based folk singer named Billy Roberts (born 1936, Greenville, South Carolina) registered a copyright for a song called “Hey Joe.” Scottish folk singer Len Partridge remembers helping Roberts with the song when they were both gigging in clubs in Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1956. In style it was sort of a ponderous country blues, in content a variation on the common folk and blues theme of the murder of a faithless mate. If anything caught the ear, it was a somberness that made it perhaps a little less jaunty about the crime than its predecessors.

In 1966 folk singer Tim Rose started getting some airplay with a version of “Hey Joe.” Rose, however, claimed that it was a traditional song that he had heard as a child growing up in Florida. Much research has failed to turn up any convincing support for Rose’s claim, but there are small hints that, while they don’t exactly corroborate Rose’s story, suggest why he might have thought of it as an old song. There was Carl Smith’s 1953 country hit “Hey Joe!” written by Boudleaux Bryant, which shared the question-and-answer format of Roberts’s lyric. There is the early twentieth-century traditional ballad “Little Sadie” about a man on the run after shooting his wife. (Interestingly, the lyrics to “Little Sadie” often locate the events in Billy Roberts’s home state of South Carolina.) Rose’s single version was a close reworking of Roberts’s slow and moody original.

But something else had been happening to “Hey Joe” in the teen clubs of Los Angeles in the meantime.

One of those things was the Byrds’ legendary residency at Ciro’s Le Disc nightclub on the Sunset Strip in the spring of 1965. The crowd of hip teenagers that filled the sidewalks outside Ciro’s waiting to see the Byrds was one of the first large gatherings of the nascent West Coast hippie counterculture. One of the songs that the Byrds were working into their set was an up-tempo version of “Hey Joe.” In the audience at Ciro’s was a coterie of Beatles-obsessed fraternity brothers from Cal State–Northridge. They had started a band called the Rockwells that played surf music and other pop covers at parties. Their first paying gig was in the Cal State gym with Captain Beefheart and His Magic Band.

Inspired by the Byrds performance at Ciro’s, the Rockwells—now calling themselves the Leaves—had a brief passage of greatness. When the Byrds left their gig at Ciro’s, the Leaves were chosen to replace them. They began to experiment with the Byrds’ suggestion of a rocked-up “Hey Joe.” The Leaves recorded and released “Hey Joe” twice before a newly recruited guitarist, Bob Arlin, added a monster fuzz-tone part in early 1966. This version of the song debuted on May 21, 1966, and became a hit, reaching number one in Los Angeles. It peaked at number thirty-one nationally and spent nine weeks on the charts.

It was fast. Oh yeah, it was fast. Not an obvious kind of fast like the fast of eighties American punk bands. “Hey Joe” was fast because velocity is the way objects become incandescent, fast in that it seemed to traverse vast spaces in two minutes and fifty-two seconds. A four-note descending stairsteps of melody—lost, lonely, and fierce—took you out to where the amplified folk chords were beginning to circle ominously, raising dust on the horizon. The Leaves used the Byrds’ idea of taking standard folk chords, the kind that might have softly caught at people’s archaic longings in the quiet of a folk club, and making them gigantic, actualizing their latent drama and sweep, leading you by that catch of the heart into a cyclone. Billy Roberts’s morose murder ballad was sucked into a desperate race to the horizon. Kids had maybe heard something like the blazing fingerpicking, jaunty as the jingle of silver, from a snatch of an overheard country station, but it was crazily fast and loud now. It sounded like weapons that had been honed in the past were being wheeled into a new line of battle, the great guns at last being unlimbered.

The party-time frat band had been given a message to deliver. “Hey Joe” sounded like nothing so much as something enormous coming to the rescue, irresistible as a cyclone driving debris before it. All over the country, kids heard “Hey Joe,” lifted their heads and sniffed the air, and knew that help was on its way. Any teenager could hear in the music that a power was rising out of the far west. Whatever was happening, the song told them, was urgent. Young people started trickling away westward, hitchhiking away from home, or taking Greyhounds headed for the coast.

The next summer came “Omaha” by Moby Grape, a San Francisco band—two minutes and nineteen seconds of what at first seemed like golden bristling chaos. “Omaha,” just as much as “California Sun,” was about getting out to the farthest west as fast as you could, but while the Rivieras sounded pretty certain that they had the expedition under control, Moby Grape discovered that the pedal was stuck to the floor, then decided what the hell, and it ends in a shriek of joyful annihilation. These were sounds nobody had heard before—at least not any adult—but young ears could hear a passionate striving in the three crazily contending guitars and frantic voices. The singer keeps saying, “Listen, my friends” then becomes incoherent with the urgency of whatever message it is he has to tell. And though the words were muddled the urgency could not have been clearer—there was a place where this extreme music came from.

They were trying to tell us about that place but not explicitly, so that we would have to finish the picture with our own response. It was only a black plastic disk, but if you closed your eyes it was panoramic, plains and canyons of light. “Omaha” came from a new and wilder frontier, with a freedom that finally felt like what had for so long been invoked but never before demonstrated.

A way of seeing began to take shape, a forgotten intuition—maybe the way certain American landscape painters had seen—that the plains and mountains were a metaphor for another kind of frontier, a frontier of imagination or consciousness. As children American kids had felt it in the movies, the Westerns, where what was exciting was not just cavalry and Indians but the huge sweep of space, the idea that the capacity of the continent for adventure, even at this late moment, may not have been exhausted. Their grade-school teachers peopled these spaces with a simple and in the end not very interesting narrative about the spread and triumph of commerce and bourgeois social organization. The students sensed a discontinuity between the sublimity and the quotidian story. The landscape of the West suggested a side of the story that for some reason the teachers said nothing about. In the end, the children realized that the people who were charged with shaping their minds were not going to offer them any other story—they were going to have to find their own path to the sublime.

But if California was paradise regained, that implied an apocalypse. And in the sixties there was a persistent apocalyptic undercurrent associated with the western edge.

Apocalypse is associated with catastrophe and judgment, the day of wrath, the End, but this is an incomplete understanding. The biblical Apocalypse is the end, but what it’s the end of is the old corrupt order and the beginning of the new heaven and earth, the New Age. It is the renewal of the world, not necessarily its physical destruction. It’s when the tables will be turned, where the last shall be first, tyrants will be brought low, and the meek will inherit the earth. Apocalypse is the original pattern of all revolutions. If there is one idea that links millenarian movements, heretical sects, peasant rebels, religious dissenters, and utopians from Brook Farm to Salt Lake City to Big Sur, it is the idea that the New Age is upon us, the division between heaven and earth has been repealed, and they are here to speed the Kingdom in and show us how to live in it. So it was in California in the sixties.

“The unstable condition of the West Coast’s population” that Phillip Lucas described above seemed to be paralleled by the very earth beneath the Californians’ feet: Atlantis-like visions of LA falling into the sea, the “Big One,” were all around. It was a given among many of the new religious movements in California in the sixties (the seedbeds of what would become the pan-global culture of the New Age) that a transformation of the planet was imminent, indeed underway, that it would render all established things—including the earth itself—unstable until the renewal had been accomplished, and, of course, that it was beginning on the western periphery.

Fig. 3.2. An aerial view of the San Andreas Fault, a symbol of impending catastrophe

As Jackson Browne, the archetypal California troubadour, sang:

Don’t you see those dark clouds gathering up ahead?

Gonna wash this planet clean like the Bible said.

You can hold on steady, try to get ready,

But everybody’s gonna get wet.

Don’t think it won’t happen just because it hasn’t happened yet.

A hodgepodge of things that had been gathering behind the dams and weirs of Western civilization since late antiquity, the source material of the counterculture and the New Age, was reaching a critical pressure on the West Coast, and in the mid-sixties it burst through. And so today, professional women in suburban offices converse about therapies, disciplines, and states of the soul that would have been blowing minds at Esalen in 1966, as easily as they talk about their children’s soccer teams. A new kind of American bohemianism, a bohemianism with the potential—lodged at first largely in its music—to become the first mass bohemianism, rolled back from the continental edge and met the wave traveling in the other direction from Britain. Before long there would be someone in almost every household who could envision a new way to be.

In 1967, the year the idea of this new Western society definitively broke out into the rest of the nation, “The Golden Road” spiraled up off the first grooves of the first Grateful Dead album, proffering an irresistible invitation:

Everybody’s dancin’ in a ring around the sun

Nobody’s finished, we ain’t even begun.

Take off your shoes, child, and take off your hat.

Try on your wings and find out where it’s at.

Hey-ay, hey, come right away

Come and join the party every day.

Now the cat was out of the bag. We’ll twist and you’ll twist, we’ll shimmy and you’ll shimmy, we’ll dance around the sun and you can too. Come out here and become angels, the Dead said to the kids in South Bend and all the other hopeless places that weren’t California. It’s bigger than you dreamed, but you can be part of it. Follow the golden road that goes west.