4

THE CHIMES OF FREEDOM

Bob Dylan, Folk-Rock, and Deep America

IN LIBRA, Don DeLillo’s novel of the Kennedy assassination, conspirator David Ferrie is driving back to New Orleans from his errand to Dallas on November 22, 1963. He drives into a violent storm around Galveston, and suddenly in the black ferocity of the storm he feels the forces he has helped to unleash, consequences that could not have been seen before the murder. He’s overwhelmed with terror. “We’ve set it loose on the land,” Ferrie thinks in a panic. “Here it is in the landscape and sky. We’ve set it loose. We’ve opened up the ground and here it is.”1

When John Kennedy was elected president, there was a disjointed underground in America that had been growing in its influence in the culture, made up of hopheads, surfers, academics, communists, jazz and folk musicians, poets, sexual nonconformists, juvenile delinquents, spiritual seekers, civil rights activists. Way too heterogeneous to be anything like a movement or a culture, the individual participants could still be seen as isolated eccentrics, kooks, wayward children at best, deviates at the worst. But it was getting clearer that something was shifting. Something in the thousand days of Jack Kennedy put into the air a notion that a Kennedy America might be a place where the desires of the underground could be harmonized somehow with the desires of the country. Kennedy was, Norman Mailer said, a sheriff that the outlaws could respect. The idea of such an alliance of outlaws and sheriff was shattered by the assassination, never to recur. The unruly energies broke from whatever hold the center still had and shot with all their pent-up centrifugal force out to the extremes. JFK had sometimes seemed like a presence that might graciously escort the country through the transformations that history was poised to rain down on it, to somehow manage it all—a person who had one side of his head in the grace of the past and one side in the wild energy of the oncoming future. Now the people felt exposed to the fury of the storm.

The consensus narrative was not able to comprehend the assassination—in both senses of comprehend: to understand, and to encompass. The consensus couldn’t entirely hold it. Despite themselves, the wise gray heads of the Warren Commission cracked open a door into a crazy night world of which most Americans were only dimly aware. The Commission’s version of the story was finally not far enough from the id of America, the secret dark inflamed places where espionage, crime, and reactionary violence crossed each other. The rational political model of events had as yet no way of publicly accounting for forces like these. The Commission’s hope was that the crack could be sealed back up, but it was too late. It could not be unacknowledged. The country couldn’t unsee the assassination. One began to have a nightmare intimation that there might not be so much space between the level of the white marble monuments and the level of the dirt and blood. But that, at the time, was underground, intuitive knowledge; it was hipster knowledge.

An impulse emerged, almost from the moment of the event, to see the assassination as part of a pattern, maybe an extension of the horrors coming regularly out of the South. It was American viciousness—the spirit of the lynch mob—seemingly carried to a sublimity of horror, the mask slipping from the awful face. A glimpse of the scale of the power that was keeping the country at once both placid and brutal. This posed a special challenge to the Left. What sense would waving a placard or staging a march make against something like this? How do you picket a blood rite?

One way to comprehend was to seek a perspective from higher up and further out. Though the Civil Rights Movement had roots in ecstasy, it presented itself largely as an appeal to reason and ethics. The assassination, whatever the final explanation behind it, seemed to reveal the limits of rationality and the appeal to a common conscience. One would have to call on something just as far beyond rationality to respond.

In the days following the assassination, Bob Dylan began to sketch out some new lyrics. The lines weren’t exactly soaring, but he was starting to work something out.

The colors of Friday were dull

as the cathedral bells were gently burnin’

strikin’ for the gentle

strikin’ for the kind

strikin’ for the crippled ones

and strikin’ for the blind.

The dark Friday of the assassination is there, and the tolling bells. But the bells aren’t just tolling in mourning. They’re striking for something, they are maybe even striking back. Even while marking defeat and tragedy, the chiming has power. Bells don’t just ring as music, they ring for something, for fire, for alarm, for a signal to wake sleepers. They’re never just sound.

Dylan was sensing an imaginative opportunity in the moment of dumb horror. That first moment of horror was the key. Dumb horror, being struck speechless, was the appropriate response. It raised a question to which no answer could be given in ordinary discursive language. Like the bells, the answer would have to have some of the qualities of music.

Dylan had begun thinking along these lines even before the assassination. He had come, he thought, to the end of the poetic possibilities of politics, and was groping for the next step. “Lay Down Your Weary Tune,” “The Chimes of Freedom,” “Mr. Tambourine Man,” songs he developed just before and after the assassination, are about hearing a great music behind events. The assassination seemed to show that the enemy was a soul-sickness, and Dylan saw that in some way it would have to be fought with on the level of the soul—of the imagination, dreams, absurdity, the psyche, angels. If the enemy could be confronted at all, it would have to be confronted on that level.

Dylan’s songs began to reflect an awareness that the line between political-economic misery and other, more subjective forms of suffering was not always straight and clear. Looked at from the angle of the soul, the forces that inflicted injustice and violence were present in everyone. It would be dangerous to overlook this. Dylan told Nat Hentoff in the New Yorker, “there aren’t any finger-pointin’ songs” on Another Side of Bob Dylan, his first album recorded after the assassination. It would have been a con—a conspiracy of falsehood with his audience—to continue pointing away from yourself when you knew for a fact that there was a Dallas or a Mississippi inside you. Dylan and his audience could go on together affirming each other’s goodness, and secretly knowing each other’s corruption, perhaps for a long time. Once having had this awareness, it would put a fat layer of falsehood under everything Dylan did if he continued to simply accuse.

The other side of that realization is that for a revolution to work there has to be a revolution in everybody. That the struggle for justice and freedom had to involve a new version of human nature—of consciousness—as well as a reordering of political and economic relations. When Dylan gets to this point, it’s one of the places at which you can say that “the sixties” begins, because this was the argument of the sixties—the merging of the “personal and the political,” that the inner remaking of man and the outer remaking of the world were two aspects of a single process; that political repression and psychic repression had to come down together, or they would not come down at all.

This angle of vision is narrow and difficult to sustain, which is why political activists distrusted it in the sixties, and still do. From the political side it looked like foolishness, and worse, self-indulgent bourgeois individualistic and possibly drug-inflamed foolishness. And dismayingly like religion. With the slightest shift in balance it relaxes into platitudes, meaningless bonhomie, passivity, narcissistic spirituality, the seventies.

In the first months of 1964 Dylan and some friends take a cross-country road trip, from east to west. A lot happens during that trip. They go to Mardi Gras, and he sees mirrored in the streets the carnival world that is in his thoughts, that will show up in many songs. It’s during the trip that Dylan’s friends first hear him talking about Arthur Rimbaud. He no longer wants to be a folk singer (to the degree that he ever was one). He wants, like Rimbaud, to be a seer. It’s also when he first really listens to the Beatles, to those chords coming through the car radio. Shortly after the trip, according to some friends, he takes acid for the first time.

During the car trip Dylan spends much of the time in the backseat with a typewriter on his lap. He writes the first draft of “Chimes of Freedom.” It contains elements from that post-assassination fragment. The cathedral bells have become the chimes of freedom, seen in lightning and heard in the thunder by two lovers who have taken shelter from a storm in the arch of a cathedral porch.

“The Chimes of Freedom” is about a politics illuminated by lightning, the way Dylan was now thinking about illuminating the old folk music with the electricity he heard in the Beatles’ “outrageous” chords. What had begun as a few lines written in response to the Kennedy assassination turned into a statement—or a restatement—of a particular American religious vision, a vision that was both mystical and political, that had been a vital artery of American spirituality up to and through the Civil War, but that had been largely allowed to melt away over the course of the following century (though it had surfaced as recently as the presidential campaign of Henry Wallace, Franklin Roosevelt’s vice president, who believed that after America had gotten the economic New Deal, it needed a “spiritual New Deal”).

At the back of the political argument for the American Revolution was a vision of America as a place where the relationship between the divine and the human could be revolutionized. The matrix, model, and metaphor for the American reordering of the worldly system of power was the reordering of the relationship between God and man. The idea was that unmediated free access to the experience of the divine for all men and women, a democratic gnosis, was a natural corollary of—in fact, the necessary precondition for—the opening of social and political freedoms. An American revolution of consciousness, as Arthur Versluis calls it, that took the accessibility of God a revolutionary—almost a blasphemous—step further.2 The vision is present from early on in America, fed by sources as diverse as English religious dissent, German theosophy, and French Freemasonry. It was advanced in the early nineteenth century by writers of the “American Renaissance” like Ralph Waldo Emerson and Walt Whitman, and on the popular level by the ferment of new religions and sects in hotbeds of radical spirituality and folk magic like central New York State, the famous “burned-over district” where people chased fireballs through the woods. The sixties trope of “changing heads” in order to create a new social order is a recognizable descendant of this tradition, with the addition of psychedelics as an effective means of democratizing the gnosis.

In our founding stories of “Pilgrim Fathers” a layer of meaning has been stripped away. The Plymouth Colony is just one example of the variety of religious dissidents who fled the crushing power of combined religious and political authority in Europe. In particular, William Penn’s “holy experiment” in religious toleration in Pennsylvania attracted a great number of small p pilgrims, many from schools of heterodox, even heretical spiritual insurgency in the Rhine Valley—Pietists, Rosicrucians, followers of the mystical writer Jacob Boehme. They differed from the Plymouth settlers in that their vision for America was not a new England, but a new world, a second chance at Paradise. The brethren of the Plymouth Plantation perceived the land as a howling wilderness populated with savages. The mid-Atlantic pilgrims saw a new Eden peopled by angels. For generations Americans have been told that their spiritual forebears were the cold Calvinists of the Plymouth Colony, but the mystical mid-Atlantic communes also left a legacy. In America their heirs would later be found at the forefront of the fight for freedom from Britain, for religious tolerance, for the abolition of slavery, and for the emancipation of women.

Take, for example, Johannes Kelpius and his Society of the Woman in the Wilderness. Kelpius is largely forgotten, but his work helped shape the intellectual environment of the American colonies. Kelpius was a young writer and musician, at the center of a group of mystically inclined scholars at the University of Altdorf in Germany. Suspected of heresy by the Lutheran state church, Kelpius’s people fled and, in 1694, founded a community on the banks of the Wissahickon Creek outside Philadelphia, where they studied astrology, alchemy, Christian theosophy, and the Kabbalah. They built a log temple with an observation deck with a telescope on top, the first observatory in America. Kelpius’s highly educated “monks” offered their services as doctors, schoolteachers, lawyers, and skilled craftsmen, free of charge to whoever sought them out, including the local Indian tribes. They compiled dictionaries of the tribal languages. The hymnal Kelpius composed is the earliest extant musical manuscript from the American colonies. After Kelpius’s death some of his followers founded the Ephrata Cloister. During the Revolutionary War, the Christian occultists of Ephrata nursed George Washington’s sick and wounded troops, and published books in collaboration with Benjamin Franklin. In the spirit of Ephrata, Utopian communes sprang up across the new nation.3

Liberating spiritual currents flowed into the American republic from many sides. The Masonic lodges in both Europe and America were seedbeds of spiritual and political radicalism whose members envisioned a free and tolerant society illumined by the common teachings of the great civilizations, a vision that found its way into the American principle of freedom of religious expression. Masons were strongly represented in the revolutionary leadership, and the founding of a new nation gave them an opportunity to put Masonic theory into practice.

Ralph Waldo Emerson, the father of American philosophy, taught that all previously restricted spiritual knowledge could be absorbed and learned freely, by any and all, from the American landscape, the “American Eden.” The Hudson River School of painters made visible the sublime power that lived in that landscape. The Spiritualist churches and the Shakers, along with their ecstatic practice, preached the abolition of slavery and the rights of women. “We are the people that turn the world upside down,” Mother Ann Lee of the Shakers told an inquirer.4 Walt Whitman, the poet and prophet of this vision, sang about a larger life and a larger self, charged with the energies of the cosmos. Whitman saw something wild and new afoot in the United States, an experiment in a new relationship between human society and the power that steers the planets, a project that took as the essential principle of spiritual and social health the notion that wisdom and energy flow from the common and powerless into the rest of society. That what energizes and redeems society comes from the bottom and not the top.

It was a vision of one kind of New World that would never entirely stop haunting the America that came to be. Indeed it provided some of its noblest ideas. It became part of a submerged river, as Norman Mailer pictured it, that from time to time would break through to the mundane America, in ways as quiet as a Quaker’s intuition of the inner light, as furious and earthshaking as the destruction of the slave economy of the South. This revolution behind the American Revolution reached its peak of energy and influence shortly before the Civil War. But as the following century went by, its direct influence faded until it was remembered mostly in quiet corners of academia. The tradition had to be grudgingly acknowledged in giants like Emerson and Whitman, but even there the drastic implications—the idea of a new consciousness giving birth to a new kind of society, a nation of self-initiated seers—became in time objects of scholarship rather than living revolutionary assertions. The vision was too close to the disreputable; it shaded off too fast into kooks and cranky celibates, mesmerism and ectoplasm. But somehow a century later the underground river came back to the surface.

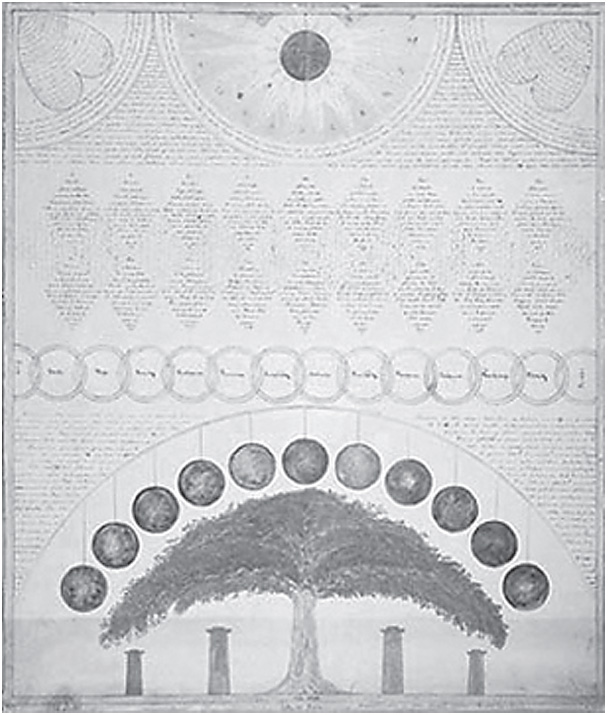

Fig. 4.1. A Shaker gift drawing, mid-nineteenth century. These were drawings of scenes witnessed in ecstatic visions.

The man standing on a street corner with the sign that says “The End Is Near” is a cartoon of the American crank, someone that dry winds have driven up some no-return highway to the dead end of American religion. But there is another kind of American apocalypticist, whose condemnation isn’t of personal sins but is, like the message of the Old Testament prophets, aimed at the crimes of a society that has fallen into error and sleep. Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech is apocalyptic, foreseeing the overthrow of the current evil dispensation for a new order that will embody a spiritual rebirth.

“The Chimes of Freedom” is also a piece of American apocalyptic. Signs in the sky, the elements themselves, reveal and authorize the vision. “For as the lightning cometh out of the east, and shineth even unto the west; so shall also the coming of the Son of man be” (Matthew 24:27). The singer and his friend or lover are enraptured and taken out of time:

Trapped by no track of hours for they hanged suspended . . .

Spellbound and swallowed ’til the tolling ended.

But the song is also specific and immediate. It begins with the couple ducking into a doorway to get out of a storm—it is as quotidian as Piers the Ploughman dozing off by the roadside on a summer day before his vision begins. They might be carrying drugs—in the song it says they’re “caught,” but by the storm or by the cops?

It is also specific and immediate in another way. The oppression that the bells are answering is personal and subjective as well as large-scale and systemic. The bells ring for the parted lovers, the unwed mother, the misunderstood artist as well as for the refugees and the prisoners of conscience. It is against oppression “in the head” as well as oppression in the body politic that the bells ring. The bells promise a revolution in the soul and revolution in society, the mystical and the political implicit in each other in a way that all the cranky visionaries of antebellum America would have had no trouble grasping at all.

In “The Chimes of Freedom” Dylan’s “topical” songs are connected to the electric “surreal” music that is coming; one grows from the other. It’s this deepening of vision that will shortly lead Dylan to his best work, his great rock and roll. This is where he begins to confess that things have more levels than he once supposed; this is where he makes his turn.

The chimes were the connection between Bob Dylan and the Byrds. The beginning of folk-rock was an attempt to realize the clear suggestion of a sound in these transitional lyrics of Dylan’s, in “Lay Down Your Weary Tune,” “The Chimes of Freedom,” and “Mr. Tambourine Man.” The waves that clash like cymbals, the bells in the sky, the jingle-jangle morning: the lyrics are so evocative that, in memory, people sometimes think they’ve heard sounds in these songs—chiming, jingling, ringing—that aren’t really there on the record. (As “Chimes” was written at the time that Dylan was first struck by the sound of the Beatles, it’s intriguing to imagine that those “outrageous” chords might have been on his mind as he wrote these lyrics.)

The three principals of the Byrds—Gene Clark, Jim (later Roger) McGuinn, and David Crosby—were all coming out of a folk-revival background similar to Dylan’s. They were all about Dylan’s age. And like Dylan they were all listening intently to the Beatles. They felt a natural impulse, almost an invitation to translate Dylan’s poetic suggestions into a sound.

A large part of the appeal of American folk music was the sound of the stringed instruments. The ring of the banjo, the filigree tone of the mandolin, and especially the richness of the guitar—the sound of the individual strings as they make up a chord, together but discernibly separate, so storylike, suggesting layers of experience, landscape, and time. In the rather ascetic environment of the folk scene, this quality was not exploited over other elements such as the voice and the lyrics. But with the rise of a generation in the late 1950s and early ’60s more attuned to the immediacy of sense impressions, to the exploration of pure sensation, to “kicks”—and with the influence of pop music that depended on novel sonic impact—new possibilities arose. Some things the Beatles were doing, such as the crashing opening chord of “A Hard Day’s Night,” suggested to younger and more freewheeling folkies what might be done.

And so we come to the story of Roger McGuinn and his Rickenbacker twelve-string electric guitar. After seeing A Hard Day’s Night, the pop-happy young folkies who would become the Byrds went out and equipped themselves with gear like the Beatles used in the movie. McGuinn got himself a Rickenbacker 360, like George Harrison.

When the Byrds as a group were eventually brought into the studio, they were very much looking for a way to give folk music the impact and directness of pop music, to bring out and foreground, make novel and almost shocking, that guitar-ness that had been the richness of folk sound. That they got this—largely via McGuinn’s twelve-string—was due to a combination of three things: the nature of the instrument, the style of playing, and the way it was recorded.

A twelve-string, because of its doubled strings, gives each note a double ring, an immediate echo and resonance, almost as if each note harmonizes with or echoes itself. This creates a “jangle” sound, the sound of multiple metallic strikes happening almost simultaneously, adding up to the impression—especially if the player, like McGuinn, is playing lots of extended arpeggios—that you are hearing quite a lot of sounds in a narrow space. Even on an acoustic twelve-string, there is still a slightly metallic or ringing sound, rather jaunty and slightly antique, like bells on a horse’s harness, a bag of coins, or boots with spurs.

Then there was McGuinn’s individual style. In contrast to other rock-and-roll guitarists, McGuinn played his guitar with the banjo fingerpicking style he learned as a teenager at the Old Town School of Folk Music in Chicago. He held a flat pick while also wearing metal fingerpicks. It didn’t sound like a banjo, but McGuinn’s arpeggios had the spring and dance of banjo strings.

Finally there was the way that Ray Gerhardt, the engineer on the sessions for Mr. Tambourine Man, the Byrds’ first album, recorded McGuinn’s guitar. As McGuinn remembers, Gerhardt “ran compressors on everything to protect his precious equipment from loud rock and roll.” But when they listened to the playback, they heard a striking effect that the compression had on the Rickenbacker. The bottom dropped out of the sound, leaving an almost Eastern clang in the sound of the striking strings. Says McGuinn, “I found I could hold a note for three or four seconds . . . like a wind instrument . . . [the sound] was really squashed down but it jump[ed] out from the radio.”

In Gene Clark’s “I’ll Feel a Whole Lot Better” from Mr. Tambourine Man, David Crosby on rhythm first sets up a chord pattern that will become the framework on which most folk-rock will from then on hang. Then McGuinn’s Rickenbacker falls on it with a feeling of sheeting or cascading, like a great bag of bells bursting open. And when the break comes, McGuinn steps up to show the world the astounding thing that can now be done with traditional folk-style fingerpicking, an intricate needlepoint embroidery of metallic sound that curls around the rock-and-roll beat that comes from American tradition but has the power of a Los Angeles garage band. It’s poignant, hopeful, and graceful and also kind of delirious: no one had heard anything quite like it.

Probably most of the LA teenagers who first made “Mr. Tambourine Man” a hit had only a nodding acquaintance with folk music as practiced in New York coffeehouses, but the sheer sonics, to a novelty-mad generation whose ears were already being taught to expect something new and exciting in pop music every few months, were a sensation. The Byrds’ sound hit with the sharpness and metallic bite that listeners already loved in rock-and-roll guitars, but here serving a jubilant lyricism.

There was a suggestion of an older dance inside the dancing that the kids did to “Mr. Tambourine Man” in the Sunset Strip clubs. There were the shifting harpsichord-like patterns that McGuinn loved in Bach (McGuinn’s break in “She Don’t Care About Time” is essentially “Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring”). “We didn’t know if we were hearing something very new or very old” a critic wrote on first hearing Vaughan Williams’s “Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis.” That’s kind of how the Byrds felt in the beginning. There was the always-new light of California in the sound, but there was dust in it too from the road that had led there. Utopian optimism was there in the guitars, but in the vocal harmonies was the story of all the time that had passed while waiting. There was a kind of confident hopeful joy that was new but that the heart had anticipated, a strong assuredness about all the wild new things that were happening, as if these young men had known it was coming, and somehow knew the meaning of it.

The Byrds and Dylan were reaching toward something that untransformed folk music could not express. Electricity was necessary to develop the implications of “The Chimes of Freedom.” It was necessary to give the chimes an audible form. The electricity of the folk-rock of Dylan and the Byrds was both literal and metaphorical lightning, and it had both a literal and metaphorical effect. The immediate sensory impact was the life and power it gave to the songs. The metaphorical, poetic impact was that it opened the door to prophecy. The electricity of “folk-rock,” like the lightning in the “Chimes” lyrics, is the heavenly part, the part from above rationality that had to descend into Dylan’s topical music, to open it up. A “topical” medication is applied only to the surface of the skin. Topical songs run horizontally across the surface of events. With that electricity, topical songs were becoming depth songs. The lightning, the vision and electricity, falls vertically, breaking open the ground, enabling Dylan to see below the surface to the buried sources of the events that the topical songs had addressed.

Standing on the stage at Ciro’s with the Byrds, looking at the dancing crowd, Dylan could see how powerful the lightning was when it was not merely evoked in words but brought down physically into the music. What he could see in that crowd was an opening to contest the allegiance of the country’s imagination. When the chips were down, the East Coast folk-music community didn’t have the vision or the power to attempt something like that. Their goals and tactics were modest and rational. Underneath their radicalism, many of them felt that all that was really necessary was to preserve and curate the traditions, to get folk songs into grade-school music classrooms. But when it came to a revolution led by teenyboppers rather than Cambridge and Manhattan bohemians, well, they weren’t so sure. Folkies may in theory have admired the idea of ecstatic revolt—they’d read Rimbaud and Ginsberg, after all—but it became clear from their affect as the 1960s progressed that they were dealing with something they didn’t really trust or wholly endorse. East Coast radicals sought progress, maybe eventually a transfer of power, but not a crack in the world.

No, the place to have the fight for the nation’s imagination was California. While it was the culture of the East Coast—rogue Ivy League academics, eccentric Episcopalians, renegade establishment scions, CIA tricksters, raving beat poets—that in a sense thought up the sixties, when it came to putting it into practice the West was the only place that was still open enough. California’s rootless and seeking population, its anomie-struck youth, could be revolutionized. Out there on the western rim, loosely moored to the rest of the continent, vibrating at a slightly higher frequency, California was the burned-over district of the twentieth century.

For the enterprise to succeed, the new music had to be on the lips and in the hearts of millions. And in California that was starting to happen. When Dylan sat in with the Byrds at Ciro’s, his army was taking shape on the Strip outside the clubs, as a new youth culture began to gather for the first time, drawn by his songs played on McGuinn’s Rickenbacker. The project was to ride the tiger.

People liked folk music for a variety of reasons. Some were utilitarian—it could be effective agitprop, a way to mobilize popular sentiment. Some were aesthetic—the old songs and instrumentation possessed a unique beauty. But there was another attraction that wasn’t easy to put into words. The eerie melodies, fashioned or preserved in the mountains, the strange images and stories brought down from some forgotten attic in the skull, suggested an imaginative grammar, a mode of perception, a code. Mystery loomed and shifted behind the music. The listeners didn’t always understand it, but they were drawn to it.

Those early American pilgrims and spiritual exiles sent their energy and ideas off in two directions from the mid-Atlantic. Some of it went to New England, to philosophers, poets, and radical clergymen. But some of the vision went into the lore of the people on what was then the frontier, in the mountainous chain that was the spine of the American east. Mountain magic. This was what exerted the call felt in the folk clubs.

The people who moved into America’s mountain backcountry in the seventeenth century were largely refugees from the slaughter and destruction that had swept back and forth across the Anglo-Scottish border since the Middle Ages. In America they simply wanted to be left alone, and left alone, by and large, they were for the next two hundred years (except by the people who came to extract the coal under the mountains, the one thing they had that anybody else wanted). For much of that time, their story was another history dismissible from the gradually forming consensus narrative. But in their language, traditions, attitudes toward life, and most of all in their music, they created a synthesis of fervent evangelical Christianity and lore that might have been taught and practiced back in Britain since premodern times.

The individual most responsible for putting that secret language in the hands of young Americans like Bob Dylan and Roger McGuinn in the 1950s was Harry Everet Smith, student of the Kabbalah, bishop of the Gnostic Catholic Church, and creator of the Anthology of American Folk Music, a man in the direct line of America’s early spiritual exiles.

Harry Smith’s story has been told many times, most evocatively by Greil Marcus in The Old Weird America. Both of Smith’s parents were Theosophists. His great-grandfather was a Union general and a historian of Freemasonry. Smith’s mother taught on the Lummi Indian reservation in Washington State. As a teenager Smith recorded the songs and rituals of the Lummi and Samish tribes and claimed he had gone through a shamanic initiation into the tribal tradition. This was the beginning of his intense lifelong interest in traditional music. After World War II Smith studied anthropology for a while, then left school to hang out with the artists of San Francisco.

Smith amassed a vast collection of old 78s, “hillbilly” and “race” records from the late 1920s and early 1930s. In 1950 Folkways records commissioned him to create a multivolume anthology from the best of his collection. Smith selected, sequenced, annotated, and designed the Anthology. It was intended by Smith not so much as cultural preservation but as an act of imaginative or magical subversion. Unlike other folk musicologists, Smith was not primarily interested in the social or political context of the music. He was interested in its consciousness-altering properties, and the anthology was designed according to occult principles. Indeed, Harry Smith already understood the music’s potential to contest the allegiance of the American imagination. In a 1969 interview with John Cohen, Smith said, “I had the feeling that the essence heard in those types of music would become something which was really large and fantastic. . . . I’d been reading Plato’s Republic. He’s jabbering about music, how you have to be careful about changing the music, because it might upset or destroy the government. Everybody gets out of step. . . . Of course, I thought it would do that.”5

The Anthology of American Folk Music showed an influential subset of a generation that a culture as strange and profound as any that could be admired in odd corners of the world existed in their own country. Coming across this music was for many the first great clue that the narrative of American life was not closed or finished or completely accounted for.

Dylan once said—famously but cryptically—that traditional American music contained “the only true, valid death you can feel today off a record player.” Here is more of the context of that quote, from a 1966 interview with Nat Hentoff in Playboy magazine. Dylan’s talking about the preservationist mind-set of folkies, their constant anxiety about the supposedly imperiled state of traditional music.

[F]olk music is a word I can’t use. Folk music is a bunch of fat people. I have to think of all this as traditional music. Traditional music is based on hexagrams. It comes about from legends, Bibles, plagues, and it revolves around vegetables and death. There’s nobody that’s going to kill traditional music. All these songs about roses growing out of people’s brains and lovers who are really geese and swans that turn into angels—they’re not going to die . . . you’d think that the traditional-music people could gather from their songs that mystery—just plain simple mystery—is a fact, a traditional fact. . . . I could give you descriptive detail of what [the old ballads] do to me, but some people would probably think my imagination had gone mad. . . . [T]raditional music is too unreal to die. . . . In that music is the only true, valid death you can feel today off a record player.6

He has a presentiment that the music contains a mystery, an initiation. Mystery—just plain simple mystery—is a fact, a traditional fact. If Dylan was ready to live the mystery, rather than just preserve it, if he could accept the real death that it held, he might come out on the other side unafraid, ready to give up the folk army he once had at his back, and begin to recruit a new army, an army of millions of teenagers who listened to the radio. But he would no longer have the steadying distance between himself and the subjects of his songs that the preservationists and curators had. He would no longer have the privileges of a guest or a tourist. He would have to surrender his letters of safe conduct.

Dylan and the other folkies had sung about a hidden history. In the next phase of his work, he started to sing like an inhabitant or protagonist of that history, but a protagonist who has followed that alternate perspective from the mountains into the streets of the incredible cities of late twentieth-century America, bringing the mystery—Harry Smith’s essence—of the mountain narrative into the city; to make the outlandish argot function as late twentieth-century street talk. It was a place no one had yet thought to put into words, but a place everyone recognized when they heard it.

Now the rain man gave me two cures

Then he said, “Jump right in”;

The one was Texas medicine

The other was just railroad gin

And like a fool I mixed them

And it strangled up my mind

And now people just get uglier

And I have no sense of time.

In the summer of 1965, a few months after the first Byrds album came out, Dylan released his first “all-electric” album, Highway 61 Revisited. Now he was singing from the other side, from inside the mystery. He had taken an irrevocable step into “the second American life, the long electric night with the fires of neon leading down the highway to the murmur of jazz.” He is renouncing the idea that mystery means tradition, the past. The job in 1965 is to find the mystery now and in America.

The last two songs on Highway 61, “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues” and “Desolation Row,” feel related, as if they’re telling one story, about a season in hell. The story might go something like this: The hero takes a bus to some desolated and hopeless corner of the continent, where every other American fugitive, junkie, and loser washes up. Maybe like Lee Oswald two years before, he takes a bus across the Mexican border. He is looking to find out the cost of living inside the myth, to see if he can stand it. “When you’re lost in the rain in Juarez and it’s Easter time too,” hanging out in a small hot dingy room looking over someplace he calls Desolation Row.

Sweet Melinda

the peasants call her the goddess of gloom

She speaks good English

and she invites you up into her room.

And you’re so kind

And careful not to go to her too soon

And she takes your voice

And leaves you howling at the moon. . . .

He survives, but changed. He’s passed through the initiation of the American night and is finally a kind of seer. His folk-rock is the fruit of his initiation. He knows the sound he wants—the “thin wild mercury sound,” he calls it. It is nothing like the Byrds. The Byrds deal in silver; Dylan’s folk-rock is gilt, the gilded rococo of a circus wagon, with an echo of calliope and whorehouse pianos, Spanish guitars, Salvation Army brass, Sanctified Church organ. And a hard, bluesy garage-rock bed under it. Strangely enough, at the moment, it is what people want to hear. “Like a Rolling Stone” is a hit, and the stories find an audience, big beyond Dylan’s reckoning.

For people who absorb Bob Dylan’s mid-sixties music, it becomes difficult to observe history with a single vision again. He has held up X-rays of America’s head, where you can see the disastrous split between the lobes, the two histories, enacted where everyone can see them. In 1966 Dylan takes his new stories out on an epochal world tour, where many people think he and his band make some of the most powerful rock and roll ever played, to test their impact, and he sees that his project has in a sense worked; the music has stirred a storm, but it is a storm that could consume him. When the tour is over he disappears from public performance for years.

The Byrds meanwhile trace a silver arc through the middle years of the sixties. They are not caught up in an agon like Dylan; they do not have a burning prophet among them; their personnel is shifting. Nevertheless, they sink a taproot to long silted-over sources of balance and hope. It’s not a simple hope that things will improve. It’s a hope for the long haul, a sort of quietly apocalyptic assurance that the movement of things is upward. They branch out from the jangle and the Dylan covers. On their album Fifth Dimension, McGuinn’s title song is a manifesto of psychedelic humanism, a slowly wheeling folk hymn recognizably in the line of William Blake and Thomas Traherne that is as memorable as any of their great Dylan interpretations.

Taken as a whole their work limns an American life of depth and graciousness, even durability. The outer edges of that life are as far out as all the consciousness explorers of the time could get, but it has a strong center, too—a vision of a way of life on the banks of the old, always new river.

As 1966 becomes 1967, there seems to be more to do, but for now, it is enough. It is all that can be absorbed. The new day that the first folk-rock heralded moves into its afternoon and utopian hope seems harder to hold on to. But a passage between histories has been opened. As the decade grows older, it is as if the Byrds and Dylan understand that it is time to rotate their fans out of the front lines. They both turn aside to the promise of rest, to the Arcadian and rooted part of the myth, in Dylan’s basement tapes and John Wesley Harding and the Byrds’ Sweetheart of the Rodeo. Now they and their fans can only wait and see.