5

THE VISION OF THE BELOVED

Troubadours, Love Songs, and the Pretty Ballerina

At the turn of the eleventh century, certain poets understood, with the force of spring, that when they fell in love something enchanted happened to them. It was not just that they were sexually attracted to their mistresses and women friends, but that the experience of being in love totally altered their perceptions of the world. . . . As they were driven to explore the essence of their sexual beings, so they experienced ever higher levels of consciousness in instantaneous but ever memorable moments of illumination.

WILLIAM ANDERSON, DANTE THE MAKER

The inexperienced novice . . . goes looking for (the Beloved) outside of himself, in a desperate search from form to form of the sensible world, until he returns to the sanctuary of his soul and perceives that the real Beloved is deep within his own being.

HENRI CORBIN, ALONE WITH THE ALONE: CREATIVE IMAGINATION IN THE SUFISM OF IBN ‘ARABI

And something strange within says “Go ahead and find her,

Just close your eyes yeah

Just close your eyes and she’ll be there . . .”

THE LEFT BANKE, “PRETTY BALLERINA”

IT IS THE middle of the 1960s, and in the Haight-Ashbury district, and in other neighborhoods like it around the world, people are riffling through the ancient pages of the book of the West, looking for forgotten stories, suggestive images and arcana, saviors and gurus, quaint formulae, lost poems. They are looking for keys to the old garden. Some of the pages carry images of figures whose fame is coextensive with the whole world—here’s a druid, and here’s Isis, and look, here’s Jesus of Nazareth! Further on, there’s Madam Blavatsky and Julian of Norwich, and the Fool of the tarot. There are shamans and medicine men, cunning folk and great magi. Some of the entries still savor of the carnival, the dark backstreet, the dusty shop front, furtive assignations—see, here are fortune-tellers and spirit mediums and Voodoo doctors. Somewhere in between, readers’ attention is caught by the corner of a jeweled page. The book falls open—many people have looked here. The pages are covered with illuminations, tiny brilliantly colored vignettes from the medieval court life of Europe. There is gold all over, gold leaf and midnight blues and shocking vermilions. People on horseback are hunting. People are dining at great long tables. There are singers and musicians. And everywhere there are couples, men and women, seated together side by side on benches, talking. Or in bed together. Adoring men are on their knees before their ladies. Arthur and his court are here, and Guinevere and Lancelot of course. A few pages further on there is a stray gleam from the Holy Grail. From the musty back pages of the West, from all the myths and scriptures and grimoires, from all the forgotten disciplines and ways, the young men and women of the sixties rediscovered Love.

In their day, those young people appeared to be riding the very wave of the future. But it’s clearer in hindsight, as Ian MacDonald suggests, that a large part of the hippies’ modus operandi was to go paging back through cultural history to unearth the most powerful icons of the past, to show that they were not just artifacts, confined to museum and university, but operative sources of power still potent and able to shake the walls that had been painstakingly built to confine and exhibit them.1

And what could be more a part of the architecture and fabric of the West than Romantic love? It was the beating heart of the High Middle Ages, an essence that ran through the Gothic cathedrals, the universities, the great mystics, the philosophers who laid the foundations of the Western mind, the lore of chivalry, the Arthurian cycle, the Grail. All these things had a glow that was a reflection of the strange songs of the troubadours.

In its domesticated form, Romantic love still is, as C. S. Lewis noted, for most Westerners (and now most of the world) the cornerstone of happiness, the centerpiece of our idea of fulfillment. Take away Romantic love and you strip away half of Western literature and music.2

The inspiration for the first poetry of Romantic love is one of the chief mysteries of European literary scholarship. Where did those troubadours of the Languedoc, under the golden southern French sun, come by this idea of a half-spiritual longing for a goddess-like lady? Lewis, the supernaturalist, left it with the comment that it was one of those revolutions in consciousness that breaks through according to an unknowable schedule. But the way back into Love as a mode of vision has to begin by grappling with the mystery of its origin. And that way goes through a land called al-Andalus.

For more than seven centuries, from the early 700s to 1492, there was a great civilization, profoundly more sophisticated in most respects than Western Christendom, right on the doorstep of Europe. It was the Arab kingdom of Andalusia, al-Andalus as the Arabs called it, Iberia, Hispania, or Spain as the Christians called it. In the tenth century the largest library in Christian Europe had about 400 volumes. The Andalusian city of Cordoba had seventy libraries, the largest of which held 600,000 volumes. In art, science, philosophy, spirituality, al-Andalus left legacy after legacy to Europe. In many ways the quickening of real medieval European civilization in the twelfth century was seeded by the genius of al-Andalus.

One of the lights of al-Andalus was the Muslim spiritual tradition called Sufism. Sufism is the living heart of Islam. The Sufis understand Islamic teaching in an inner, metaphorical, and poetic sense rather than with the literal and external understanding of the fundamentalists. One of the greatest of the Sufis, and the one best known in the West, is the Persian poet and mystic Jalaladin Rumi. Rumi wrote things like this:

From the beginning of my life, I have been looking for your face . . .

I was you

and never knew it.

(Or as the Small Faces later sang: “Words seem out of place / all my life I’ve known your face.”)

For the Sufis, divine love for God and erotic love for another human being were not opposed things but a continuum. One led to another, if you kept your heart open.

The Sufis’ explanation of this kind of love is simple but enormous in its implications. Lovers see each other the way God sees each of us. The feeling of the intense significance that lodges in the beloved, the sense that he or she gives all of life meaning, is nothing but the plain truth, the Sufis would say, and true of every one of us. In God’s eyes each of us is as essential to the meaning of the world and as irreplaceable as the beloved is in the eyes of the lover. We may only see this mystery in a few people in our lives, maybe only one. God, the Sufis said, in his mercy prevents us from seeing the true radiance of every creature, lest we be blinded by the light from the angels around us.

As Henry Corbin says, “Who is the real Beloved? The answer is quite precise: the soul . . . contemplates God in all other beings not through its own gaze, but because it is the same gaze by which God sees them . . .”3

When we are in love we are momentarily given the gift of seeing a person, our beloved, with the vision of angels. To know this is to instantly have a new and much more accurate knowledge of the reality called God. It is a thousand times more accurate than theology or dogma can provide, because you will have experienced it. Your beloved is your way, revealed to you. The growing delight, the sense of everything being transformed, the sense that the world revolves around the beloved, the way he or she gives life meaning and purpose—this flows from seeing the angelic nature of another person.

And so the seed of what we would later call Romantic love was found, and planted and watered by these holy men. And because the Sufis loved poetry, they wrote poems about it. And because poetry and music hadn’t split apart yet, they made songs. They were songs to someone or something called the Beloved, and it was never completely clear whether they meant God, or a particular human, or both.

Perfumed breezes from this erotic spirituality wafted from al-Andalus to the sun-filled air of southern France. According to literary historian Maria Rosa Menocal, in eleventh-century Spain, groups of wandering Sufi poets and singers went from court to court, and sometimes even traveled to Christian courts in southern France. Contacts between these minstrels and the French troubadours were regular. So Love came to Christian Europe, and it had a startling effect. Soon the murderous Dark Age warlords were falling on their knees not before their feudal overlord but before . . . women. Women, who had no military or political power at all. Women, who had been little more than bargaining chips in the coarse power plays of early medieval Europe. Western society had been missing half its soul, and when it caught the virus from al-Andalus it began to look for it. What the men saw now when they looked into the eyes of their lady undid them; it knocked them out of their saddles and turned their world upside down. These Gothic louts started to sing. Grim Duke William of Aquitaine came home from his bloody work in the Crusades to set down his heavy broadsword and start plucking with thick fingers on a little stringed device called a lute. They wrote poetry. They were becoming civilized.

The followers of the Lady were put in touch with spiritual realities upon which the church had never instructed them. The lovers and their ladies were working on intuition and instinct as they built a new code of behavior to house the new vision. They didn’t call what they saw in their lady’s eyes God. Their priests had never told them that the Divine could be so close, so delightful, so real, capable of touching their hearts and setting them on fire this way. They sensed they were on the border of heresy. The church agreed. It began to sniff out an Eastern and heretical scent.

The gentled men and their ladies called it Amor, Love, Love with a capital L. It was, they decided, the greatest thing earthly life had to offer, and the Western world has agreed with them for the past millennium. One way to grasp the size of this shift in consciousness is to understand that for most men and women in the history of the human species up through the Middle Ages, the combination of what we call being “in love” with the idea of marriage would have seemed eccentric; the idea that a happy marriage must be based on the bride and groom being “in love” with each other, a strange whimsy. In many parts of the world it still does. But such was the power of this new experience that love, in time, became the whole point of marriage.

People couldn’t stop writing about it. The central texts of this new European civilization, after the Bible, were the stories of the reign of King Arthur, whose kingdom rose and fell on surging waves of Love. In the leisured classes of feudal Europe, love stories and love songs were all anyone wanted to hear. Poets turned out tales of the amorous intrigues in the court of Arthur as fast as they could be read and circulated. Eventually this kind of story came to be called Romantic, because most of the Arthurian stories were first composed in the Romance languages, in French or Italian. Soon the Germans and the English took it up. In years to come everyone, even the most humble, would believe that they were destined for Romantic Love, that Love was part of their birthright. Thousands upon thousands of popular songs celebrating love would pour forth over the centuries, in a river that leads right up to the place where we stand now.

The troubadour’s songs had lyrics that have echoed for nine hundred years, as in this anonymous fragment:

Western wind,

when wilt thou blow?

The small rain down can rain.

Christ that my love were in my arms,

and I in my bed again.

Eventually, Love became a part of common human nature, no longer an elite and esoteric mystery. But when a culture, en masse, opens up its spiritual ears to a new frequency, the culture may take a step up, but the frequency often slows and eventually ceases to challenge the older world as much. After enough time and familiarity, the experience may become commodified, turned into something that can be bought and sold.

It was not long after the rise of large-scale capitalism in the wake of the Industrial Revolution, and the concurrent birth of mass media, that Love, inevitably, got sucked into the engine of commerce. An industry sprang up to batten on people’s love of love songs. Modern popular music was born. With the new business of mass entertainment, the love song went from being a popular form to a popular product.

In the huge new market of the United States, popular song became an industry, starting in the nineteenth century with the sentimental parlor songs of composers like Stephen Foster, continuing through to the rise of the American musical theater and the giants of the “Great American Songbook.” Brilliant singers like Hoagy Carmichael, Frank Sinatra, and Sarah Vaughan performed songs by composers such as George Gershwin, Irving Berlin, and Cole Porter. Sentiment, when deployed by gifted writers and vocalists, could convey genuine movement of the heart. Sometimes even the seemingly trite and ephemeral took on more depth as time passed. The simple love lyric that sophisticates sneered at a generation ago may one day resonate with the poignant hopes of a lost era, like some of hits from World War II.

Poetry rides an uneasy seesaw with commerce but finds ways to hang on. But the field became awfully crowded. Commercial popular music in the first half of the twentieth century was glutted with glib trivia cranked out by those who in time would be lumped together as “Tin Pan Alley” hacks—the moon-June-croon school of mass-produced sentiment. The hack became a stock character, a cynical peddler of cheap dreams who has cashed in his stock of soul, happily putting a dollar figure on every piece of human feeling he can set a price on.

But there was a new force coming into popular music in the late 1940s and ’50s, one we will meet again and again. The black church in America, as we’ve seen, was one of history’s great schools of sacred music. Apprenticeship in a gospel choir with a demanding musical director regularly produced supremely expressive musicians: musicians who often had the charisma of inspired preachers, who were used to the idea of music moving people on the deepest levels. Eventually, many of these musicians tried their hand at secular music, and they brought a startling new electricity and depth of feeling to popular song, a power that many white people began to respond to. Singers like Sam Cooke and Aretha Franklin, to name just two, showed that their gift of soul was transferable from the church to the jukebox. The long string of secular hits from artists like these changed the spiritual experience of pop music, infusing an implicit promise of deliverance into even the most ostensibly worldly love songs.

Flourishing at the same time was the world of the saloon singers, the crooners, and the after-hours chanteuses. In this smoky world, a carapace around every heart was assumed, a carapace built up of many affairs, much boozed-up sex, many broken hearts, many deals cut with life, lots of ideals burned through in a cloud of bourbon fumes and cigarette smoke. The archetypal saloon singer is, of course, Frank Sinatra. Stephen Rojack, the hero of Norman Mailer’s An American Dream, is his counterpart in literature. For the Sinatra protagonist, as for Rojack, love is sometimes given as a perilous second chance, a grace that might be able to crack the carapace and let the angel out, a shot at redemption when you’ve blown every other chance. The whole scenario is a potent piece of American poetry, but it’s very much a world for adults. Not just any adults, either, but ones who have been around the block a few times.

So it was significant that while the crooners were crooning, a vast new audience of kids was forming. Rock and roll was building this audience, delineating it and giving it its style. The words teenager and rock and roll entered the language at about the same time in the 1950s, and for most adults, both had unsettling implications. Teenagers would demand and get music of their own and love songs of their own. But unlike the heroes of Sinatra or Mailer, most of the people in the rock-and-roll audience didn’t need a redemptive second chance—most of them had yet to blow their first chance. And so the songs that were written for this new audience, and the ones they would later write for themselves, have a very different feel. Through an accident of shifting taste, demographics, adolescent hormones, and (later) psychedelic drugs, rock and roll would never entirely lose this first-time innocence in the face of love.

A gate was opened and through it came a torrent of love, a rebirth of the lyric spirit in the form of young guitarists crafting two-and-a-half-minute pop songs. The golden age of the sixties love song is the period that began when the Beatles broke internationally in 1964 and ended with the emergence of self-consciously serious and drug-drenched pop, eventually to be called “rock,” in 1967.

Even before the Beatles there were stirrings: R & B artists Ben E. King and the Drifters were moved to write soaring, wistful visions of the strange beauties to be momentarily encountered and enjoyed in the heat and grit of New York City. In 1961 King created a jewel of urban lyricism called “Spanish Harlem” in very much the mood of Leonard Bernstein’s songs for West Side Story. Elvis himself seemed to acknowledge a new mood when he released the stately “Can’t Help Falling in Love” in 1961. In 1963 Dusty Springfield, a white soul singer from London, rode in on cascades of strings in “I Only Want to Be with You,” a gorgeous tune that set sublimity to a dance beat in a manner that many would try to duplicate.

But by 1964 the Beatles were in the vanguard of the rebirth of romance, working toward a new way to sing about the powers that moved young hearts. “And I Love Her,” “Things We Said Today,” “Every Little Thing,” “What You’re Doing”—in these four songs, recorded in the space of twelve months, the group began to map out their own romantic landscape.

“And I Love Her” is the earliest and most conventional. It is typical of the clean, almost frosty freshness of early Beatles music. Paul loves clichés, so there is a little Latin amor in the guitar playing, but you’re willing to be moved because of the purity of the emotion, which takes something quite simple and even a little trite and walks it up to the edge of a refreshed innocence, as if you are hearing this kind of song naïvely again, and then the Latinisms really do add a kind of mystery to this starry night. Paul’s feeling is so unadorned and pure, everything so simple and still, that, even here—so early on—there is a hint of a timeless space that opens in the starlight where the lovers look into each other’s eyes.

“Things We Said Today” is another moody one but the mood has gone from Latin romance to Romantic brooding. Under a gray English sky, the singer (Paul again) has an intuition of the present moment, with his lover, as already a memory, recalled in a future where he may well be alone. A brusque guitar ostinato yanks him back to the present over and over, but the flow of the song and his reverie want to stream to a dark horizon. It is an unusual note on love’s scale, not sorrow, but love with something somber on its mind—an unfamiliar variety of romantic mood with the tang of real experience.

In “Every Little Thing,” John Lennon sounds genuinely like a man whose life has been saved by love, who can’t quite credit the grace that’s been extended him. Ringo’s stately drumming helps the song unfold with a kind of joyful solemnity. The understated but unguarded emotion in John’s singing would became a dominant mood of the sixties love song, the kind of emotional honesty that would later make John a trusted guide out on the frontiers of psychedelia.

“What You’re Doing” was the most sophisticated thing the Beatles had ventured up to that point. Ringo’s unaccompanied tom-tom snaps things to attention, setting this mid-tempo plea moving along assertively. George follows Ringo’s rhythm with a repeated, spare silvery pattern of notes, one of many times one can hear connections between the Beatles and American folk music, which is matched by Paul and John’s especially astringent harmonies. Everything has a slightly rough edge that builds a powerful feeling of emotional directness. Paul’s lyrics are a protest against the romantic convention that permits cruelty from the beloved toward the lover, an appeal to the beloved to remember ordinary kindness. Again the Beatles find an interesting emotional place just a little to one side of convention, creating a moving love song that yet seems to have no recognizable love-song conventions—in fact, that implicitly criticizes the conventions.

All together in such a compact moment of time, these songs suggested a composite sensibility—Beatle love. Beatle love would be the score for the sexual maturation of millions of adolescents around the world. How did it feel? It felt as new as the first experience of romantic attraction. It didn’t come trailing moth-eaten conventions and stock imagery. It felt honest. The Beatles’ singing style was intimate yet unsentimental in a way that did not have much precedent in popular song. The emotional expression felt direct and open. It felt washed clean of the unctuous and saccharine, free of sentiment or seduction. And, more difficult to describe, there was a color or texture to it that was nearly palpable: a rose-colored dawn feeling, a sensation of beginnings, of uncorrupted possibilities, that seemed to say that the old Western lovers had had a new birth.

But it was not just the Beatles who were spreading the word. Songs began to appear on the radio that seemed to understand the same sorts of things about love. One hears in these songs little melodic figures like aspirations of the heart. Listen to the Searchers recording of Jackie DeShannon’s “When You Walk in the Room” (1964) and to that rising and falling guitar figure that opens the song. It is unabashedly electric and metallic, but also lilting and graceful, the sound of the new lute. Sixties rockers were in love with electricity, and musicians were fascinated by the very physical composition of their guitar strings and the different sounds that bright metal plus electricity could produce. Couldn’t they make a bright silver sound, a sound that didn’t try to duplicate a gut-stringed acoustic guitar but that reveled in its metal-ness? Heavy metal is the phrase that has stuck in the rock argot, but when you listen to early sixties music you hear a different school of metal. By emphasizing the metallic nature of the strings, groups like the Searchers made the electric guitar a perfect instrument to fashion a new romantic atmosphere. The gold or silver notes that rose and fell were airy, but at the same time spoke of the weight of the singer’s infatuation. They carried an echo of church bells, calling to sweet remembered depths. But at the same time that there are remembered bells, there’s a hint of an Oriental clang in the sound, just enough to help defamiliarize the experience the singer is describing, to add a strangeness to stock descriptions of puppy love. And all “When You Walk in the Room” is really about is the effect that a particular girl has on a young man when she enters a party. So it fills one function of art: it reminds us of the edged intensity of experience before it becomes familiar.

From Manchester in the industrial Midlands of England came the Hollies, who could at their highest moments go toe to toe with the best of their era. They broke out with “Just One Look” and “Here I Go Again” in 1964, crafting a remarkable sound, both buoyant and muscular, a wall of bracing interwoven harmony around ingeniously catchy songcraft. The Hollies layer hook upon hook, voice upon voice, until the song can hold no more and their message bursts joyfully forth, as in hits like “I’m Alive” (1965), a story of redemption by love that manages to be solemnly heartfelt and delirious at the same time.

In 1964 the Zombies introduced their elegant, jazzy rock and roll led by Rod Argent’s electric piano and Colin Blunstone’s breathy vocals. “She’s Not There” (1964) first establishes their sultry understatement only to get progressively more unsettled and urgent until Blunstone starts gasping and raving at the chorus. They followed up with a series of sophisticated, beautifully rendered singles, including “Tell Her No” (1964), “I Love You” (1965), and “Time of the Season” (1968).

There was a misty melancholy not so far below the surface of these songs, a mode of feeling perhaps more familiar in Britain than the United States. Two English duos—Chad and Jeremy and Peter and Gordon—demonstrated a similar gift for exquisiteness with a pang in the center, with Chad and Jeremy in “A Summer Song” and “Yesterday’s Gone” (1964), both cobweb-delicate and poignant, consoling all the boys and girls for whom autumn winds spell the end of romance. In 1964 Peter and Gordon started on a string of hits that used American folk-style harmonies to cage a breaking English heart, in songs like “A World Without Love,” “I Don’t Want to See You Again,” “I Go to Pieces,” and the epical “Woman” (1966).

Herman’s Hermits have been dismissed as a lightweight boy band cashing in on Beatlemania, except that they kept turning out songs with more spirit than they should by rights have possessed, starting in 1964 with Gerry Goffin and Carole King’s “I’m Into Something Good,” a rendition that treats this sweet piece of pure pop with all the élan it deserves, and continuing into 1965 with the exuberant “Can’t You Hear My Heartbeat,” and the wistfully lovely “Travelling Light.”

In the States, 1964 saw the Beach Boys beginning to hint at the ache of love songs yet to come with “Don’t Worry Baby,” where the band found something sumptuously timeless in a teenager’s fear of an upcoming drag race, and the solace offered by his girl.

Out of Motown Records in 1964 came a succession of love songs with a feeling not widely heard in pop before or since. Representative was the Four Tops’ “Baby I Need Your Loving,” typical of the foundational soul technique of translating the pulpit’s emotional testifying style to the bandstand. The Four Tops continued in this vein with a string of highly original hits that shared an ominous, almost panicky mood, strange in the noonday of the mid-sixties. “Reach Out, I’ll Be There” (1966), “Standing in the Shadows of Love” (1966), and “Bernadette” (1967) are highly dramatic, almost desperate, raising the stakes of love to what sounded like matters of life and death.

Motown was, of course, the domain of Smokey Robinson and his group the Miracles, and many people would have no problem calling Robinson the greatest love-song writer of his era. Smokey sang his heartbreak with elegant grace, and songs like “Tracks of My Tears” (1965) evoked the natural nobility of a grieving heart. Robinson also served as The Temptations’ primary songwriter, and among the hits he wrote for them was one of the era’s definitive love songs, the prayerful “My Girl.”

But at the midpoint of the sixties, you didn’t need to be a giant like Robinson with a list of hits a yard long to get to a similar place. In 1965 the Vogues, a singing quartet from Turtle Creek, Pennsylvania, appeared on the charts with the wholly euphoric “You’re the One.” The Seekers, from Australia, prefigured folk-rock as Judy Durham’s rich contralto and the resonant acoustic guitar in “I’ll Never Find Another You” (1964) lent the moral earnestness of folk music to a vow of romantic fidelity.

Running through many of these varied pieces of ostensible teen ephemera, whether the mood was euphoric or dejected, was a sense of reverence. Whether the emotion is delight or disbelief or even dread, there is a sense of wonder at what is happening to the subject that could be heard not just, or even primarily, in the lyrics but experienced in the sonic impact of the whole song. When the Hollies sang “I’m Alive,” they didn’t just sing about a man who had been numb for years being resurrected by love; the whole song, in its buildup to the ecstatic release of the hook, enacted the process.

When professional songwriters in the 1950s wanted to signify a serious emotional depth in songs aimed at the teen market, they might go for operatic bathos (“Tell Laura I Love Her”) or resort to the trope of teen death behind the wheel of a car or on a motorcycle (“Last Kiss,” and so on). In contrast, in 1965 when the Byrds sang “Here Without You,” lovesickness took on a dignity that validated and gave weight to what the adult world would dismiss as adolescent moodiness. Young people who heard their experience set to music in such songs sensed that this was music they would not look back on later with dismay or derision; it was music they felt they might listen to their whole lives. And they were right.

When Brian Wilson sang “God only knows what I’d be without you” in 1966, it wasn’t just a convention: he meant that love had actually saved the singer’s life, and that’s exactly what it felt like. What you hear again and again in these songs is a hushed respect for this power. The Association’s “Never My Love” (1967) has the quiet of a chapel with an organ heard through the walls; the Righteous Brothers’ “Unchained Melody” (1965) soars like an Ave Maria. Even the bright pop of the Turtles’ “You Baby” (1966) is not simply happy—there’s joy as the singer stops in the middle of the clangor and chiming to say:

A little ray of sunshine

A little bit of soul,

And just a touch of magic

You’ve got the greatest thing since rock & roll . . .

Sometimes the solemnity would cross over into a bittersweet sadness, not just in the heartbreak songs but even in the songs of love fulfilled, a suggestion of a kind of sorrow at the heart of joy, a mood encountered more often on the operatic stage than in pop songs. The Jefferson Airplane’s “Today” (1967), sublimely sung by Marty Balin, is a powerful example. In a very different mood, Van Morrison arrives at a similar place as he invokes the spirit of a long-lost lover in “Brown Eyed Girl” (1967).

But even less emotionally complicated love songs had a bite. A series of arresting, sharply sketched romantic vignettes found their way onto the charts. An abandoned lover anguishes over his choice of words in the Grass Roots’ marvelous conflation of folk-rock and Latin-tinged percussion, “Things I Should Have Said” (1967); a grieving lover feels his grief turning him into an untouchable in the Beatles’ “Hide Your Love Away” (1965); and in something as simple as Manfred Mann’s “Pretty Flamingo,” all that happens is that a young man watches an unattainable girl in a red dress walk down the block. These songs and others like them—the Beau Brummels’ “Just a Little” (1965), the Rockin’ Berries “He’s in Town” (1964), the Tremeloes’ “Silence Is Golden” (1967), to name a few—gained considerable emotional impact by copping to love’s complicated emotional textures.

As the decade progressed and the concerns of the musicians became more recondite, the image of the beloved was sometimes charged with hints of metaphysical significance. One might have expected this from Dylan, and his “Visions of Johanna” (1966) would not disappoint, with its evocation of a woman whose presence is everywhere and her human form nowhere.

It remained for a touch of grace to close out the golden age, and for two such disparate characters as John Sebastian of the Lovin’ Spoonful and Lou Reed of the Velvet Underground to provide it. In 1967 Sebastian followed what had always been the open heart of his band to a natural consummation in “Darling Be Home Soon.” And Reed gave “I’ll Be Your Mirror” to Velvet Underground singer Nico, and the result was a magic song from the crystalline forest that the Velvet Underground seemed to inhabit, though in the end its simple but profound theme was love as an act of pure generosity.

There were two conditions of early sixties rock and roll that colored the way performers felt and wrote about love.

One was that early sixties rock and roll was a music made, for the most part, by young people for young people. The experience of first love and the troubadour impulse to sing about it was nearer to the average rocker than to the average professional tunesmith simply because the average rocker was still in his teens, and so was his audience. The American songbook was full of songs about love written by adults for adults. This sophistication was one of its great strengths, but inevitably jadedness crept in. It was an unstated assumption of early sixties rock and roll that the performers were mostly singing for people who were not yet worldly, whose experiences had the clarity and intensity of the first time.

Then, to a degree unprecedented in commercial popular music, sixties pop singers were writing their own music, a pattern largely set by the Beatles. Today this is unremarkable, and the balance of taste has perhaps swung back toward a renewed respect for the art of the interpreter. But at the time, it gave a novel freshness and immediacy to the experience of pop music. Listeners responded to that freshness the way travelers in a desert respond to water. The hold that the hack had held for generations over the romantic imagination of the West was loosened.

Together, these two factors made a distinct difference in the emotional tenor of the hit love song. It seemed as if the mode was sloughing off generations of built-up layers of lacquer, to emerge new and dewy, as if the senses that had been jaded and tainted by Las Vegas oiliness had awoken in a morning where they were innocent again. Instead of the crooners, with their persona of the worldly romantic veteran giving love one more shot, a new school of pop song sought to express the high of young love.

One of the myths of sixties music that is actually true is that a great deal of inspiration was spread promiscuously around, and many unlikely young men or women listening to records in their bedroom or practicing guitar in the basement had a shot at being Orpheus or Sir Phillip Sydney. Again and again in those years, rather ordinary boys and girls were touched for a moment, for a song—or two or three—that maybe never broke out of the local charts, but that touched the heart as powerfully as anything done by the famous heroes of the era.

We now turn our attention to one of those boys and his eternal, unforgettable broken heart.

Michael Brown was his name. A generic name, for certain, but let’s look closer. Both parents are Jewish, and all the Michaels that have ever been named are named after Mi-kha-El (in Hebrew, “Who is like God?”), the prince of the angels. Jewish parents who name their son Michael cannot be unaware of the connection, which may not necessarily be what they really want for their child. Invite angels in and affairs can take funny turns.

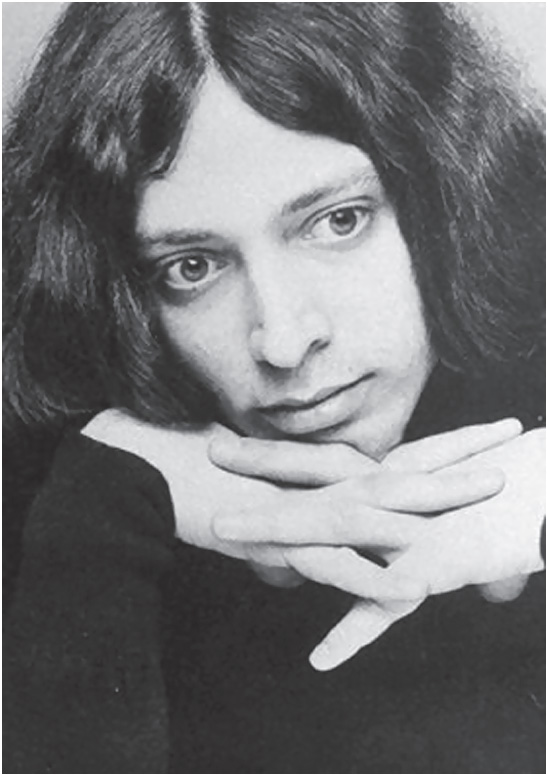

And in fact his last name wasn’t even really Brown. It was Lookofsky. Michael’s father was Harry Lookofsky, a classical violinist and well-known New York session musician. It’s not perfectly clear when or why Michael Lookofsky became Michael Brown (the most plausible explanation is that “Lookofsky” hardly sounded English enough for this teenage Anglophile). In any event, he was known as Michael Brown by the time he was sixteen. Michael’s father supplemented his musician’s cash flow by operating a small recording studio at 1595 Broadway in Manhattan, called World United. True to his heredity, Michael was a musical child, and his father had him in piano lessons early. By adolescence, it was clear to his father that the studio was one place where his awkward son was happy, tinkering with the instruments and the control board. When Michael was fifteen, his dad gave him his own set of keys to the studio, a gesture that bespeaks not only trust that he won’t wreck the equipment, but an acknowledgment that this was where his son needed to be. At age sixteen, the year our story starts, Michael was tall, gangly, with a studio pallor and wide dark eyes that seemed to be looking inward at the same time he was looking at you.

Not far away, in an old apartment building in Greenwich Village, an avuncular middle-aged hipster from beatnik days had set up a crash pad/salon for a group of kids who were beginning to explore the city. The scene at the apartment attracted a vanguard of high schoolers who had been touched more deeply and seriously than their peers by the new British rock and roll, kids who took being fans one step further and wanted to somehow be a part of the energy they felt in the music, maybe even a source of it themselves.

Fig. 5.1. Michael Brown of the Left Banke

One of the early regulars at the apartment was a tall, dark-haired seventeen-year-old named Tom Finn, an orphan who was on the run from the city’s foster-care system. He had become for his age fairly proficient on bass guitar and could sing, too. There was also a girl who hung out with Tom and his friends who became, in the casual manner of the times, Finn’s girlfriend. Her name was Renee Allen (last name changed), and she was attending New York’s High School of Performing Arts. Like the others, she was interested in trying out different modes of expression. She was a singer. She was a dancer. And she was beautiful—beautiful in a way that can instantly and completely conquer the heart of a certain kind of young man. She was tall, fair, with wide blue eyes that, like Michal Brown’s, seemed to balance an inner and an outer gaze at once. But the impact of her physical presence was magnified and made more fascinating by an air she carried of cool quiet and a hint of mystery; it was as if, although her beauty placed her among the natural royalty of the teenage world, she already understood that that was not all there was to it.

Her corona, her crown, was her hair. She was a blonde. But not just any kind of blonde. She was a platinum blonde, her hair like cobweb-fine strands of white gold, worn long, straight, and parted in the middle in the style of the day. She had the kind of blonde presence that seemed, as with certain very charismatic people, to alter the air around her, leaving a photoflash afterimage on the retina, and the space she had occupied charged for an instant after she left. “I seemed to feel not one presence but two, an ash-blonde young lady of lavender shadows and curious ghosts, some private music, a woman with a body one might never be allowed to see in the sun; and then the other girl, healthy as a farmer, born to be photographed in a bathing suit.”4

At sixteen Renee was already facing a choice—to be a muse to someone else, or to follow her own muse. To be the queen of hearts, for whom men will craft beautiful things, or to submit to an artistic discipline, to go through the training and apprenticeship like all the rest. In the end, Renee would decline goddesshood and become an artist, but at sixteen, she hadn’t decided. It was in that year that she went with Tom Finn to Harry Lookofsky’s studio and met Michael Brown.

Tom and his crew from the Village were aware of Michael and the studio. One day Tom and some of his friends showed up at 1595 Broadway. To the would-be rockers Tom was hanging out with, Michael had two big things going for him. One was that set of keys to his dad’s studio. The other was his proficiency on keyboards. Tom and Michael discovered a shared passion for the sort of elegant chamber-pop that English groups like the Beatles and the Zombies were crafting. Eventually Michael suggested that Tom and the others come by the studio after hours and fool around with some music.

When the group showed up at the studio, Tom Finn brought Renee, and a door opened for Michael Brown. It was a door into blue sky, which to set one foot through was to plummet. Michael plummeted. He was sixteen and had no nets to catch him. Later, he tried to fashion nets out of songs, but that didn’t help him any more than it has ever helped anyone. The cool lavender-shadowed presence in the studio, perched on top of the amps, became his magnetic north, his polestar.

You could say he fell instantly and completely in love. But that ordinary phrase makes what happens to love’s victims seem too easily comprehensible. Maybe he saw something when he looked at her that he knew he had been made to have. In the early morning hours in the studio, after everyone had gone home, Michael worked on songs. He was abashed in Renee’s presence, tongue-tied and awkward. But in the imagination of his heart, it was not an awkward one-sided infatuation. It was an epic, the biggest thing that had ever happened to him. And it was also, at the same time, already a tragedy.

Ay! Now she steals, through love’s sweet theft,

My heart, my self, my world entire;

She steals herself and I am left

Only this longing and desire.

BERNART DE VENTADORN5

The latest addition to the proto-band was a Puerto Rican kid named Esteban Caro, or Steven Martin-Caro, as he started calling himself. Tom Finn had literally bumped into him one day while running from a group of girls on Broadway who had mistaken long-haired Tom for a Rolling Stone. Caro had heartthrob looks, soulful eyes, a thick mop of shiny black hair—and he could sing. A natural rocker he was not, but in the general infatuation with all things English, he had fashioned bits and pieces of different singers into a vocal persona that expressed teen ardor with the yearning purity of a chorister. Michael Brown heard something in it close to the mood of his songs.

The little group who gathered at World United Studio gradually took on the shape of a band. They had a bassist in Tom Finn, a singer in Steve Martin-Caro, a keyboard player and songwriter in Michael Brown, and two others from Tom’s Village crew, George Cameron on drums and Jeff Winfield on guitar. Most nights the group would end up gathered around Michael’s piano, extemporizing bits of songs, finding parts they liked, discarding others.

Eventually, one night, they were “busted” by Harry Lookofsky, who arrived at the studio unexpectedly to find the group smoking weed and jamming. Harry hustled them out, but Michael stood his ground. He pleaded with his father to listen to some of the ideas they’d been working out. Lookofsky—musical instincts prevailing—relented. The kids returned a couple of days later. They plugged in and shyly began to play some of the songs they had been working on.

It had been getting clearer for some weeks now, as the band tinkered and played around with Michael’s ideas, that something was taking shape. Most rock and roll up until that point had relied on the singer to tell the story. The rhythm section kept the kids on their feet, and the lead guitar could add color but its expressive power was limited to a short break in the middle of the song. But in the world of Harry Lookofsky and his son, there was a whole orchestra full of ways to help tell the story and fill out the emotional color of a song, options that Michael didn’t intend to renounce simply because he was playing rock and roll. And so a creative tension was set up at World United. The guys in the band would push Michael to rock like Johnnie Johnson, Chuck Berry’s keyboard man, and he would for a couple of numbers. Then they would try out one of Michael’s own compositions, and the piano would take the lead, pulling the instruments into a new relationship with each other, striving toward melodies ornamental and fragile as a glass Christmas-tree ball. Over time the ornament, living within the lurch of rock and roll, became more durable while the rock and roll became more subtle.

There was something graceful and poignant that could be heard in the snatches of melody that Steve would pick up and sing, passages that opened out into levels of romantic experience that had not been much explored in teenage music. There was a song tentatively called “Shadows Breaking over My Head” that no one quite understood except that, yes, it was about a girl, and it sounded like an invitation down a dark garden path just before a storm.

To his credit, Harry Lookofsky could hear that his son, with his years of training and his natural inventiveness, was trying to solve an artistic problem. Was there a way that pop music, rock and roll, could validly and gracefully access the much broader emotional and sonic palette of symphonic music without coming on like a bumpkin in borrowed finery?

Michael Brown was not the first or only rock and roller to think about this. In this moment of triumph for rock and roll, there was an imperial mood among successful young musicians that looked to annex pieces of previously unexplored musical territory. The year before, the Beatles had caused a stir with the release of “Yesterday” scored for strings by their producer George Martin. The Rolling Stones had added memorable color and texture to their furious “Paint It Black” with snatches of Middle Eastern and Indian classical modes.

While any number of people might have thought about using symphonic techniques and instruments in rock and roll, far fewer had the resources and the chops to actually attempt it. And fewer still had a vision that made such a fusion not just interesting, but natural and necessary. Michael Brown did.

At World United a creative coterie had been assembled whose members each brought a piece that together would allow this experiment to work. Four teenage rock-and-roll waifs from Manhattan together brought the makings of a tight little pop band; another teenager brought a lifetime of classical training and a rare ability to translate emotions into melody; Harry Lookofsky brought a recording studio, which most young bands would have given their eyeteeth just to see the inside of, and he brought collegial relationships with half the working classical session musicians in the city.

Harry assumed the role of producer. He listened to the bare bones of Michael’s songs as the boys worked them out; he could understand the effects they were trying for, and working with the band, he helped them translate that into a clear artistic blueprint. As a professional musician, Harry decided that the next thing the band was going to need was charts. Charts—anathema to the rock-and-roll spirit, then and now. But Harry saw that this band, his son’s band, was trying for something special and he thought he saw a way for them to get it.

Lookofsky brought in a friend of his, a musician and arranger named John Abbot, who joined the circle at the studio. In the early months of 1966, night after night, they would stand around Michael’s piano: John Abbot, Harry Lookofsky, Michael, Tom, Steve, George, and Jeff. The boys demonstrating ideas for Abbot and Lookofsky, who would suggest ways to realize them. Eventually, Abbot felt ready to start rendering some of these ideas in concrete arrangements.

All that was the process that any visitor to the studio might have seen. This part of the process was interesting, but it mostly fell within established protocols for the way music was made. But there was another and unseen process going on, one that would have just as much impact on the music, but wasn’t about music as such, and didn’t fit any established protocols. To Michael Brown, the most important person in the studio wasn’t in the group around the piano. Renee, the girl who wanted to sing and dance, but who right now wanted to see how rock and roll was made, was still showing up regularly with Tom to hang out.

No one else could see it or know it, but while working under Renee’s gaze Michael was living out a story, a story of love and loss, that he could never bring himself to tell anyone, especially not Renee herself, but that he would tell nonetheless. If a third party had access to Michael Brown’s thoughts, the power of the feelings would have seemed out of all proportion to any objective events. But that is, of course, often the way with love-struck sixteen-year-olds who are not wholly at ease in the world.

From the moment he desired her, she had been gone. She was someone else’s. And, really, there didn’t even have to be someone else. In Michael’s mind, you just had to look across the studio, from him to her, to see how ineligible he was. Why should she stoop to lift him up? Yet even so, it was still not easy to understand. How could she be the answer to his heart’s desire, unless she was meant to be his? And yet she was not his. How could all his desires come together in her, and she be so unaware of it? All in the moment of first meeting her, he had seen his great hope realized, and his great hope vanish. What a child’s belief, that she would see in him a fraction of what he saw in her. What a small hopeless hope that was. So it was not just grief he felt, but despair.

But there was one thing Michael did have that was irreducible, and in it he thought he saw a way. A kind of way. There was music, the one working conduit between his heart and the outside world. He may have been incapable of speaking his feelings, but he could extract beauty from them, and then it would not all have been meaningless. And maybe she might even glimpse herself in it, as she was reflected in his heart, and then she might know.

With his literally unspeakable longing, Michael Brown had stepped into interesting company. He was not the first, after all, to have his world turned upside down by a girl he could not speak to. On May 1, in the year 1274, Dante Alighieri, then nine years old, was roaming the bustling streets of Florence with friends when something about one of the clusters of people passing by attracted his attention. It was a color that caught his eye first, and he never forgot it—a streak of red, deepest crimson, shocking as blood in the dusty street. There was a family group, a mother, father, and three daughters. They were the prosperous Portinari clan, one of the families of merchant princes of the city. But it was not the prominent father at which the boy was now beginning to stare. It was one of the girls, eight-year-old Beatrice Portinari, who was clothed like a flaming angel in scarlet silk, vivid against her pale skin. And almost before Dante was aware of it, it had already happened. That was all the time it took, the event that would shape the rest of his life and art, to fall profoundly and forever in love with the girl who would guide him to the center of Paradise. He says that he was in a stupor. There were times when he felt he could not remain alive and feel love as intensely as he did, that it would physically overwhelm him. When he was near her, he found it hard to stand unsupported. She became his muse, the inspiration of The Divine Comedy, Europe’s great poem.

But there’s something else in this story, a fact and a behavior so out of tune with modern life that we no longer have a name for it. There is no indication in Dante’s writing that Dante Alighieri and Beatrice Portinari ever spoke to each other. She is the soul and central image of his life’s work, yet they may never have had so much as a conversation. We may choose to view this as a product of the bizarre conventions of Catholic Europe, the kind of thing that makes us glad we live on this side of the Reformation. We may find it impossible to imagine such a story in the present. But in fact it happens often. We don’t hear about it a lot because, of those who experience it, few have the ability to make their private experience shared and public. But Dante Alighieri did. And so did Michael Brown.

Like many lovers before him, Michael Brown took leave of his unattainable lady and started working on a song. In one sense he had nothing to write about—there was no broken love affair, he had no relationship to grieve, there was no farewell to be said. What she had been for him—a casual acquaintance—she presumably would continue to be. But in his inner life, an entirely different story was unfolding, and that was the story Michael wanted to tell. His heart was broken, and he resorted to the set of conventions that we use to describe broken hearts, the stories of love found and lost. There was no other way to convey, in the context of a pop song, the degree of loss he felt.

Fig. 5.2. Dante and Beatrice

The band had laid down the basic tracks for a few songs, and there was some promise in them. The Left Banke, as they were calling themselves, sounded enough like a competent sixties pop band to give them the confidence to try something more, some nearer realization of the sound they had all started to hear. Until now Michael’s harpsichord had been used tentatively, to decorate the standard guitars-bass-drum figuration of the typical sixties combo. But what they all were looking for was not decoration but fusion, or rather, an idea that demanded fusion in order to express itself, so that there would be nothing arbitrary or merely experimental about it. When Michael brought the idea for the song about his lost love into the studio, as they worked on it, it didn’t take long to see that they had what they needed.

Did the lost love in the new song need to be named? No—Michael gave her no name in the lyric. But for some reason he wanted to name her, and he put the name in the most prominent place he could—the title. It must have been an uncomfortable moment in the studio when he told them all, the name he’d given the song—his inner life, his dream sorrow made public. He called it “Walk Away Renee.” One day, years in the future, there would exist more than a hundred recorded versions of it, and it would appear on Rolling Stone’s list of the five hundred greatest songs ever written. It would come to be recognized as one of the most memorable love songs from an era that produced scores of them. In it, thousands of the heartbroken would see their despair distilled into beauty.

Fig. 5.3. The Left Banke

But at that moment, there were real people implicated in the song’s creation. Renee had become what she was deciding not to be. She, like it or not, had been pulled into the process. She was something more and less than herself—she had been made a muse, and partly a muse she would remain as long as people listened to this song.

Working with the band, John Abbot created an arrangement for two violins, harpsichord, flute, electric bass, and drums. The violins were scored as lead instruments, stepping into the place usually occupied by the guitar. John Abbot and Harry Lookofsky saw a chance to develop a broader expressive palette for the Left Banke than almost any pop band of the era enjoyed, even the superstars. They were going to give rock and roll a new set of tools for depicting more intense and varied emotional states.

The sound that the group at World United created took teenage heartbreak and placed it in the main current of Western tradition, ready to match depth of feeling with Tristan and Isolde, reminding the world that Romeo and Juliet was a teen-heartbreak story, too. Gorgeous and desolate, the strings and flute of “Renee” picked up on a yearning and dreamlike quality of youthful pain, moving past the marker that the Beatles had laid down with “Yesterday.” The lyric and the arrangement were one emotional piece, not arbitrarily paired. The effect was to enlarge the stereotypical situation at the heart of the song, to give universal resonance to a young man’s sorrow.

“Renee” begins in medias res, as if interrupting a reverie, the first word—“And” suggesting that the internal monologue we’re listening in on has been going on for a while.

And when I see the sign that

points one way

The lot we used to pass by

every day . . .

Just walk away Renee,

You won’t see me follow you back home

The empty sidewalks on my

block are not the same

You’re not to blame.

For people beyond a certain age the tasks and obligations of adulthood help keep sorrow from encompassing the universe. But a very young person with a broken heart has learned no limits to their sorrow. For a sixteen-year-old, grief informs the whole world. In “Renee’s” specificity about the details of place—the one-way street sign, the vacant lot, the empty sidewalks, the heart scrawled on a wall—everything the narrator sees embodies his sorrow. It is similar to, or perhaps a version of, visionary experience, when every piece of the physical environment is fraught with meaning and has a theme. The music is lush, but the images are plain, concrete, urban—the fabric of the city where Michael Brown was growing up.

The young man’s emotions are not described—that would risk bathos. Instead it’s suggested by those concrete images. That puts weight and incisiveness behind the strings. The same combination of the pretty and the plain characterizes Steve Martin-Caro’s singing. It’s lovely, almost effete, choir-boyish; it strains after a high monotone, wrought up to one pitch of emotion until, when he sings about his weary eyes, we can feel his exhaustion.

The chorus is like the arc of yearning, a heart striving toward its object, each time surging gorgeously only to fall back again like a wave, the music striving toward the girl while the words are telling her to walk away.

The last line of the chorus—“You’re not to blame”—is one of those items you could put in your brief when pleading for the moral seriousness of rock and roll, and one of the main reasons that this song has been taken into so many hearts. Unlike all the sneering young men of rock and roll, bitter at their girlfriends, glorying in emotional revenge or sexual triumph, here, at the end of every chorus, the heartbroken young man reassures Renee that his pain is not her fault. The singer does not assuage his pain with self-righteous put-downs. Out of the center of his pain, in a gesture of spiritual generosity, the singer releases her from any emotional debt.

Astonishingly, yet inevitably, the group of teenagers and their adult mentors watched “Walk Away Renee” become a national hit, reaching number five on the national Billboard charts in July, 1966.

At this point the Left Banke had put themselves beyond the achievement of most of their peers among the American bands that had risen up in response to the British Invasion. It was a vertiginous place for a bunch of teenagers. But there was something more to be done. Not just to follow up a hit, but also in the inner, artistic work. The Left Banke’s great breakthrough was that they didn’t stop with heartache. Somehow they decided to follow the arc of the story beyond pain into a most unusual place, a place where even adult songwriters didn’t go—indeed didn’t know about. A place like the ones where the courtly lovers of Provence, the intoxicated Sufis of al-Andalus, and Dante Alighieri of Florence had gone—into a mostly forgotten byway of Western tradition that Michael Brown and friends had, half-knowingly, consented to work within.

When Dante began writing about his love for Beatrice Portinari, he sent the first poem, as if seeking comment or as a letter of introduction, to a rather mysterious group of young poets who collectively called themselves the Fedeli d’Amore, the faithful of love. The purposes and the actions of the Fedeli have always been obscure. Different guesses portray them as an aesthetic society for propagating poetry in the common language of Italy, as a revolutionary cell dedicated to overthrowing the feudal order, or a heretical mystical order, perhaps a covert Sufi tariqa or a lost branch of the Knights Templar.

What seems to have been at the core of the Fedeli’s interests was the idea that romantic love, if followed wholeheartedly, could be an initiation into a nobler spiritual condition, what we would call a higher level of consciousness and what they called the cor gentile, “the gentle heart.” Devotion to one’s lady and service to the god of Love, Amor, was a path of spiritual work to develop the cor gentile.

If you viewed your lady with the terrifically concentrated vision of love, while she never ceased to be a real, particular human woman, she was also revealed as the donna angelicata, “the angelic lady,” and as such became a source of spiritual guidance, knowledge, and illumination. Through love (as we’ve seen), we become angels to each other. This was not necessarily brought about by any kind of relationship with the lady, by becoming her lover in any sense in which we would use the words today. If she didn’t know you existed she could still be the donna angelicata to you. Each one of the Fedeli searched for and found his lady. He would meditate on her face as a place where the natural world and the angelic world intersected.

The secretiveness of the Fedeli was a necessity because their practice challenged both pillars on which medieval society stood—the feudal social system and the church. This collaboration of Eros and the Holy Spirit was not one that the church was ready to contemplate in the fourteenth century. As William Anderson says, “The danger, where the church was concerned, was that by finding the individual way to divine knowledge through his lady . . . the poet was bypassing the necessary mediation of the church, and indeed declaring his independence of its teachings.”6 And the Fedeli were just as much a contradiction of the feudal social order of medieval Europe. They believed it was the cor gentile that made a gentleman, not aristocratic birth, power, or wealth, and that the gentle heart could be attained by anyone willing to give his whole heart to his lady and his loyalty to the god Amor. That is why these poets of the “sweet new style” were committed to writing in the vernacular Italian rather than the Latin of the elites—their message was for all the people. In this way, the Fedeli d’Amore positioned themselves squarely in the midst of that central if turbulent Western current: the impulse to democratize spiritual experience. This underground stream of ecstatic politics was cresting again in the 1960s and was seeping into Harry Lookofsky’s studio on Broadway in the waning months of 1966.

In a cultural moment when the gratification of all desire was more and more held up as the greatest good, older voices spoke to Michael Brown, voices of devotion and renunciation, vows and sacrifice, and they seemed to make more sense of his experience. If you are utterly desirous of your beloved, yet utterly bereft—but if you maintain your devotion— a kind of way may open where there had been no way. Something about the beloved becomes visible and clear to you in a way that it would take a lifetime of ordinary human partnership to see. Michael Brown imagined a love, a beloved who was a golden-haired dancer, like Renee, but her hair was so brilliant it hurt his eyes to look at her. “La donna della mia mente,” as Dante said—“the glorious lady of my mind.”

The very definition of true love in Arabic poetry was “desire never to be fulfilled.” When one learned to live with yearning, love sometimes opened out into an ocean on the far side of heartbreak. The West had mostly lost interest in talk like this, and the idea had receded into the storerooms and musty archives of scholarship. But that was changing. Imaginative channels were opening in 1966, conduits from the plane of poetry and vision were pouring out the old wine freely. Vision was being spread about again, just as in the first centuries of romantic love, when the feelings and states of consciousness that had been whispered in the secret courts of queens and princes began to be sung in the streets. In such a moment, there was no reason why a shy teenager from Manhattan couldn’t wade out into the depths.

As Michael Brown worked and wrote, surrounded at times by band members and arrangers and session musicians or by himself in the early morning hours in the studio, after the others had left, he was deeply under the sway of Amor, the terrible god who had come to Dante in a flame-colored cloud. Did Love come to Michael Brown in the studio as he came to Dante, to show him, before his eyes, his own heart on fire? By this time Michael knew that artistically he had moved beyond the point of heartbreak. With the creation and the mass response to “Walk Away Renee,” he had mastered that trope and told that story. But he was still in love. The real story, he was beginning to see, must have a culmination other than farewell. He was beginning to see that the Fair One may be as deep inside of him as she was far away from him on the outside. Or that in the experience of Renee’s presence, he was seeing part of his soul.

And so Michael Brown was working in an inspired state, under the direct patronage of a goddess. As the Sufi sheikhs had experienced, as the most devoted of the troubadours saw, as Dante knew who followed his Beatrice through Purgatory to the center of Heaven, Michael saw that he still could be, had to be, true to his love, even though he could never possess her. Like a medieval lady, Michael Brown’s Beloved laid on her lover a charge: Tell the world what this is like, she said. You told the world what it was like to lose the flesh-and-blood girl. Now tell them about the “Beloved deep within your own being,” the beautiful lady of your mind. Tell them about the donna angelicata.

Inside the studio, one was aware of only the most subjective kind of time. But outside it was November 1966, eight months after the “Walk Away Renee” sessions. The Left Banke had a national hit. They were no longer a bunch of kids hanging out, fooling around with grown-up toys during the studio’s downtime. Now there was money involved. They were professionals and they were under a contract. It was time to produce the follow-up. The song was called “Pretty Ballerina.”

A woman on the Left Banke’s Facebook page has left a message about how, as a four-year-old, she heard “Pretty Ballerina” one day when she was alone at home and how it had frightened her. She isn’t the only one to respond to a certain presence in the song. On the evening of April 25, 1967—Michael Brown’s eighteenth birthday—Leonard Bernstein, the face of classical music in America, sat down at a piano on national television and played a passage from “Pretty Ballerina.” Something about Michael Brown’s song had jumped the gulf between World United Studio and Carnegie Hall.

Bernstein tried to describe for his audience what that something was. He said the melody sounded “Turkish” or “Greek,” which was simply a way of saying it sounded strange, as if from a place some distance away. This, Bernstein explained, is an effect of the mode the song is written in, the particular family of notes Brown drew on to create the melody. “Pretty Ballerina” combines elements from the Lydian and Mixolydian modes. The combination of these two puts the song in a mode that doesn’t exist formally in Western music, making it feel exotic, as if it holds secrets. This is part of what scared the little girl. But that’s not all.

From its first seconds, it is clear that “Pretty Ballerina” is heading somewhere different from most love songs. Its aim is not to tug at hearts, but to induce vision. While “Renee” began with four elegantly sad descending notes on cello and viola, the first thing that attracts your attention in “Pretty Ballerina,” running underneath Michael’s simple piano figure, is not melody at all, but a drone—an E-flat drone established by Harry Lookofsky and a colleague playing one note together on two slightly out of tune violins, the doubled instruments giving the drone a vibrating, apprehensive quality. Ordinary secular music, with its changes, patterns, and progressions, is always linked to time, it moves in time, keeps time with its rhythm in a linear development from one moment to another. The drone is outside of musical timekeeping. It doesn’t progress, change, develop, or decay—all traits of things that happen in music and in time. A drone is what timelessness sounds like when it is depicted in the world of time. From Indian ragas to Sufi zikr music to Celtic pipes to medieval plainchant to John Cale’s electric viola in the Velvet Underground, the drone has been deployed to facilitate trance. It is the aural analog of the single point of concentration employed by Christian contemplatives, Zen monks, and hypnotists to focus attention and pass through the awareness of time. The effect of the drone is dreamlike, but not at all like sleep. You should be alert, it says, even wary.

Besides the drone and the employment of a mode that would strike most Western ears as foreign, there is something else that works to effect this mood of wary alertness, something that you feel as soon as you hear the first notes of the melody curling like a vine around the drone. For “Pretty Ballerina” is built around a dissonance, the most famous dissonance in Western music—the tritone, or more colorfully, the diabolus in musica, the “devil’s interval”—the distance between “Pretty Ballerina”’s E-flat center, and an intruding A-natural. The tritone is the most common technique for creating dissonance, but use of it was banned for centuries by the church. The church wanted to hear only “consonant” not dissonant intervals because consonant intervals were derived from natural overtones and therefore pleasing to God. They considered the tritone the father of all dissonance, hence its attribution to the Father of Discord. Even when the church no longer dictated musical conventions, Western composers instinctively followed the ban on the tritone for generations.

The “dissonant” part of the melody of “Pretty Ballerina” is made of two alternating notes, repeated half a dozen times per line—like a child’s singsong chant, or a music-box tune. The G-natural alternates with the dissonant A-natural, back and forth with each note, the diabolus at work. With the two notes, a slight unease is created. On one hand we may be in a child’s world contemplating a music-box dancer. Then the dissonance betrays the presence of a larger mystery.

The mode, the drone, and the dissonance build a palpable sense of a presence. The atmosphere is both tensely vibrant and very still; the air is charged with the imminent appearance of . . . what? Then the story begins, and we become aware whose presence we feel. It’s the Ballerina herself—the Angelic Lady.

The girl is no longer exactly Renee, not even exactly human. In the earlier song, Michael Brown explicitly gave the girl what he thought was her real name—Renee, walking away, in the act of being lost to him. Now the girl does not have any one name, she is defined by one thing she does—she is the pretty ballerina. She moves neither toward nor away from him; her only motion is that of a dancer twirling slowly to the haunting music-box simplicity of the melody. She is made of some qualities of a human girl and others from a world only Michael Brown was seeing. Renee’s platinum-blonde hair is there (that hair that looked like it was affecting something in the light in the air around her)—in the dream now he cannot even look at it directly, it is so brilliant it hurts his eyes.

All the musical elements speak of stasis. But a pop song must have lyrics, and the lyrics must tell a story. What story do the lyrics narrate? How do they extend the meaning of the music? Steve Martin-Caro acts the part of a young dandy, a sort of fin de siècle aesthete, a collector and connoisseur of beauty. The singing is restrained and almost mono-tonal (the monotone of a person trying to verbalize a dream while still half asleep). His singing is pretty and wistful but forced to a sweet high pitch, lending a sense of fragile artifice: beautiful, still, and cold as a Chinese vase. The drone and Martin-Caro’s vocal reflect each other.

The young man approaches the unapproachable ballerina, a girl he can barely look at directly. He asks for a dance. Beyond all hope, his courage is rewarded. She says yes.

I had a date with the pretty ballerina

Her hair so brilliant that it hurt my eyes

I asked her for this dance

And when she obliged me

Was I surprised, yeah

Was I surprised, no not at all

The young man knows the rules of the game they are playing. He knows them in his head but not in his heart. He is a novice in love. He is the scullery boy whom the princess has smiled upon. He is Sir Perceval, the gauche yokel who wants to find the Grail. He knows he shouldn’t call her too soon. They’ve made a date. He should have faith. Grasping at her might make her disappear. But of course, he calls her. Worse, he asks her if she loves him. He begs her to tell him.

I called her yesterday

It should have been tomorrow

I couldn’t keep

The joy that was inside

I begged for her to tell me

If she really loved me . . .

He knows that he has broken faith. He has tried to test the dream. He remembers what people say about faith moving mountains. “Somewhere a mountain is moving,” he reflects wryly. “But then it’s moving without me.”

That’s all there is before the break. And that’s all there really is to the story of the young man and the pretty ballerina. But that’s not all of the song.

Once again in the Left Banke’s music, the violins take the break, and we are in Romany, with Gypsy colors. The break is in two parts connected by an ostinato on the bass. After that pause the violins move us east, to the eastern edge of Europe, where Leonard Bernstein heard the source of the song, toward Hungary, Bohemia, and the Balkans: a world of red-velvet drapery and bleeding hearts. The song pauses, there’s a moment of silence.

There’s a little more to the story. The piano’s discordant nursery rhyme begins again. The singer speaks in the present tense now. The story of the ballerina he told as if it were in the past. But this is happening now.

And when I wake on a dreary Sunday morning

I open up my eyes to find there’s rain

We knew it would be raining. This is not a song for the sun; this is a song composed when the world is asleep, by candlelight, by a dandy in his cold perfection, looking out on Sunday morning across the thousands of rooftops of the city, glinting silver-gray in the rain, the spires of Bucharest or the water tanks of New York, the uncrossable expanse between him and her. He has been exiled back to the world as it was before he first spoke to her, where she is unattainable.

That’s when the voice comes:

And something strange within says

“Go ahead and find her,

Just close your eyes, yeah,

Just close your eyes and she’ll be there.”

Renaissance poets believed that when you looked into your own heart, what you saw was an image of your beloved at a level where it no longer had any meaning to try to determine what was you and what was her; your identities were fused, even if your love was unrequited. You were not one solitary, unified self anymore; part of you was another. “If I could make the world as pure, and strange as what I see / I’d put you in the mirror I put in front of me,” sang Lou Reed in “Pale Blue Eyes.” Or is it that love reveals to you a part of yourself that is always there, waiting for a human face to wear—muse, obsession, soul, fate, daemon, angel: “The glorious lady of my mind.” After the experience of Amor, that part of you that you thought was most your own will always wear the face of another. Is that how Beatrice led Dante through hell and heaven, years after her death?

She’ll be there . . .

The young man has gone through his initiation into the mysteries of Love. He is no longer, as Henry Corbin says, “the inexperienced novice (who) goes looking for her outside of himself, in a desperate search from form to form of the sensible world.” No, he has come to the point where “he returns to the sanctuary of his soul and perceives that the real Beloved is deep within his own being.”

Just close your eyes and she’ll be there.

She is the one who comes in dreams. The one who will never walk away.

She’ll be there . . .

The ballerina turns on the music box, reflected in her mirror. Will he join her out of time in her music-box dance?

She’ll be there . . .

Martin-Caro sings again in his high monotone as the drone turns homeward.

She’ll be there . . .

The young man has business in that place from which the drone comes, so he follows it back into silence and darkness, beyond the places we can see or hear.

As the A-side of the Left Banke’s second single, “Pretty Ballerina” did well—it reached number fifteen on the Cashbox charts for 1967—but not as well as “Walk Away Renee.” In fact, it was the last thing like a hit the group was to have. Today, you’ll hear it occasionally on the radio, but it has never made its way onto the standard playlists of the oldies stations. Indeed, there seem to be four people who will sing along with “Walk Away Renee,” for every one who still hears “Pretty Ballerina” in his or her head.

But like the original Fedeli, the Left Banke left behind testimony to the consciousness-changing potential of erotic love—the path to the knowledge and enjoyment of God through one of His creatures. It is this intimation that gives so many sixties love songs their shimmer. There are few of them without some trace of it.

It’s possible that there are no sixties love songs directly influenced by “Pretty Ballerina.” But in so vividly invoking the psychic dynamic of Amor, the state where Eros touches eternity, the Left Banke made it easier to detect its presence—or absence—in other people’s songs, and made it harder to try to sell a love song that didn’t take you somewhere within hailing distance of the inner landscape of “Pretty Ballerina.” As Robert Graves says of the White Goddess, the muse of European poetry, you can tell her presence in a poem by the hair that rises on your arms when you read it. Just so, you can tell when the ballerina is present in a song.

There is a poignant, upward-turning, troubadour aspiration in the mood of sixties love songs, from “Unchained Melody” to “Pretty Flamingo” to “Darling Be Home Soon” to “Visions of Johanna” to “Today” by the Jefferson Airplane, to the vortex of grief and loss in Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks. For a few years, the Lady walked again, and you could hear her presence in the ring of the silver strings and the harmonies that sounded like the meaning of breath.