11

THE VISION OF CHILDHOOD

The Incredible String Band and British Psychedelia

Far off, like a perfect pearl, one can see the city of God. It is so wonderful that it seems as if a child could reach it in a summer’s day. And so a child could. But with me and such as I am it is different. One can realise a thing in a single moment, but one loses it in the long hours that follow. . . .

OSCAR WILDE, “DE PROFUNDIS”

Shades of the prison-house begin to close

Upon the growing Boy, . . .

WILLIAM WORDSWORTH, “INTIMATIONS OF IMMORTALITY” FROM RECOLLECTIONS OF EARLY CHILDHOOD

Footfalls echo in the memory

Down the passage which we did not take

Towards the door we never opened

Into the rose-garden. . . .

Shall we follow? . . .

Round the corner. Through the first gate,

Into our first world . . .

Go, said the bird, for the leaves were full of children,

Hidden excitedly, containing laughter.

T. S. ELIOT, “BURNT NORTON”

When I was a boy, everything was right.

THE BEATLES

I REMEMBER especially the crying in the night, coming from somewhere down the long corridors of the old dark house. I remember the girl getting out of bed, in a kind of dream, putting on a robe, taking a candle, and following the sound through the silent halls. I remember liking the idea that the house was so big and labyrinthine that there were places that even if you lived in the house you might never see, that there might be a secret story going on somewhere in the depths of the house, a night story behind the daytime story. And I remember the old woman seated in front of the classroom, reading the story to us, and this was back when stories were one of the ways in which things really happened to you.

Not that many years later, but a world away from third grade, I heard Robin Williamson sing,

Born in a house where the doors shut tight

Shadowy fingers on the curtains at night

And it made me remember the old dark house on the moors, the house that had marvelous children living in it.

The story my teacher read to us was Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden. The song was the Incredible String Band’s “Koeeoaddi There.” “Ah,” I thought when I heard the song. “Of course.” It didn’t really surprise me that I was going back to that house, back down the long dark passageways that I hadn’t had time to finish exploring before childhood ended.

Fig. 11.1. Cover of The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett (illustration by M. L. Kirk)

Robin Williamson’s strange house “on the mournful morning moors” merged with Frances Hodgson Burnett’s. “Koeeoaddi There” goes on to sketch a story in suggestive fragments, which I blended with other fragments that I half remembered from Burnett’s book, and some things that were just my own responses to the song. Marvelous children roaming freely through an old dark house, surrounded by adult mysteries and intrigues. Greeting the “Invisible Brethren” (a secret society, perhaps, or maybe ghosts?), the guards and ministers who watch the children as they go ice-skating.

I was sixteen and it was 1969. A strange, dark year, the decade in its throes (sometimes just saying the name of the year brings it back—there is a kind of iron taste in the numbers), sitting on mattresses in basements lit by candles. People’s trips were turning out not necessarily bad, but dark and weird. (My girlfriend and I walked out onto a stubbly cornfield on a frosty night, on the country edge of the suburbs, and became convinced that the field was full of buried bodies that we were walking on top of.) In the cold early months of that year we did not picture the child’s-eye vignettes of the Incredible String Band lit by sunlight; no, the illumination we imagined would be more like the stage lights of a pantomime theater, casting deep shadows. Images in the songs that a year before might have seemed playful and light took on a weight from the growing somberness. It felt a lot like the sense of loss and falling night that is the undercurrent of The Lord of the Rings. The Incredible String Band occupied the same moment as the MC5 and the Weather Underground. Where we lived, in Chicago, there were days of rage and fire in the streets. In the String Band’s Britain they were finding bones in the foundations of the house. How close stories of childhood sometimes are to the Gothic.

O tell B for the Beast at the ending of the wood (Goodnight, goodnight)

You know he ate all the children when they wouldn’t be good. (Goodnight, goodnight)

In another song there is a boy who has visions in his bedroom and won’t come out, fierce visions of an ancient warrior he calls “Swift-asthe-Wind” whose flashing sword drips blood and who has a pile of skulls at his feet. His parents want him to come down and play with the other children.

There is no blood

No-one knows all my child

You must stop imagining all this

You must stop imagining all this

For your own good

Why don’t you go with the rest

and play downstairs?

This connection to childhood (a childhood that was perhaps not even our own) was somehow part of what landed on our American doorstep along with the British music. The new music did, on one hand, what popular music always does for adolescents—it was about sex and independence and trying to cultivate an attractive and slightly risky exterior. But somewhere in the music and in the stance of the bands, beneath the sex and aggression and coolness, there was an attitude that suggested you could maybe hold your teenage angst a little lightly, that coolness too was a kind of convention, and that there was something anterior to coolness that might be even better.

You can observe this thing in the scene from A Hard Day’s Night when George wanders into a hip London ad agency or PR firm, a place whose purpose is to monetize every shifting tremor of cool in the capital. The secretary is a splendid Swinging London dream, her boss an epicene and twitchy hustler. They’re sure George must be one of their creatures, but they’re a little puzzled, something about him doesn’t quite fit. They think he might be an outrider from the Next Thing, but they check and find that the Next Thing isn’t due for three more weeks. The point is that the hip shirts they show George, the swinging young TV hostess they’re sure he listens to, get the same beautiful effortless Beatles dismissal that the banker who barges into their car on the London train gets. These desperate speculators in cool are as absurd as the most out of touch of the older generation. George, the most impassive of the Beatles, possesses something that eludes the hippest marketer or the most perfect of blonde dolly birds, something that precedes cool, of which cool is a nervous impersonation.

This other thing, I understand now, was a kind of innocence, a thing that had not yet been caught by the world, that stands apart from the world, yet, as the Beatles demonstrate, offers a fantastically effective way to enjoy it.

The whole of A Hard Day’s Night in one way is about how strange and comical the world appears to perceptions that are essentially innocent. The Beatles are four Alices, and the world of the entertainment biz they’ve fallen into is the other side of the looking glass. The Beatles refuse with gentle incomprehension every gambit and temptation offered up to snag them into this world where people are desperately trying to make things happen or not happen. Though they are young men, they are very much like boys. Shortly after George’s encounter they escape from the television studio, and what do they do? They kick a ball around an open field. And later Ringo, alone, breaks away and joins a band of hooky-playing mudlarks on the banks of the Thames.

As Beatlemania became a culture, there grew a feeling that part of a person should always remain innocent in this way. If you are boiling down the sixties counterculture to one proposition, you could do worse than that. As with most of the interesting things that were implicit in the Beatles at the beginning, this became explicit as time went on. English pop musicians found the connection between psychedelics and childhood innocence so obvious that it hardly needed explaining. The Beatles, inspired by their own psychedelic adventures, decided they were going to do an album-length suite about their childhoods. But by then they had already heard the Incredible String Band.

The Incredible String Band—Michael Heron, Clive Palmer, and Robin Williamson—started life in the folk clubs of Edinburgh in the early sixties (the scene we last saw as the birthplace of “Hey, Joe”). Their original repertoire was standard British and American folk-revival tunes, and the occasional whimsical original. Their time spent woodshedding in the clubs gave them a grounding in traditional song that would one day be a prominent strand in the elaborate braid of their music.

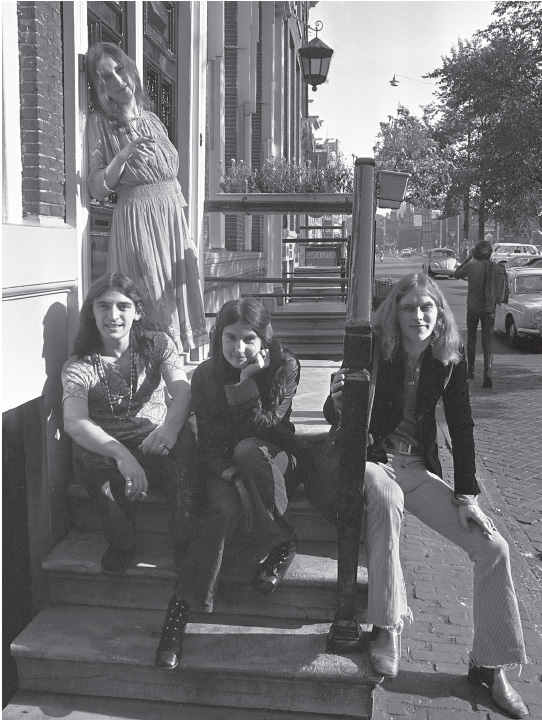

Fig. 11.2. The Incredible String Band (photo by Bert Verhoeff)

In 1967 they went their separate ways, Robin to Morocco, where he became entranced with Middle Eastern music and began to assemble the core of what would become a fantastic collection of instruments. They also started taking acid, which took them into worlds of experience that the repertoire of a conventional coffeehouse folk group was not capable of expressing.

Inspired by Robin’s adventures, and his collection of instruments, the re-formed duo (now minus Clive Palmer) began to pursue a musical idea that would do two different things at once. They would weave together threads of musical and mystical traditions from half the globe, a kind of British Empire of the psyche, stretching from the Celtic fringe to the Indian subcontinent. At the same time they entered deeply into a child’s-eye vision of their own culture.

Robin and Mike were spotted and taken under the wing of the visionary manager and producer Joe Boyd. In early 1967 Boyd got them a series of dates at London folk and psychedelic watering holes and they quickly became the exotic new favorites of London’s musical elite. The Beatles and the Stones were fans (Paul said that the String Band’s The 5000 Spirits or the Layers of the Onion was his favorite album of 1967), and the soon-to-be principals of Led Zeppelin, Robert Plant and Jimmy Page, were in the audiences and came under the influence too.

In the United Kingdom 1968 was the String Band’s dizzy height. There was beginning to be the sense of an establishment and an underground within rock and roll itself, and the String Band became the face of the British underground at that moment. Rarely has something so close to pop stardom been conferred on something as eccentric. But at the moment it made sense. The ambiance of 1968 in London was like a Halloween party—festive but getting spooky, overheated, theatrical, slightly hysterical, a comic-book version of Aubrey Beardsley. It was the great era of crushed-velvet hippie fashion flamboyance, and as such it might have been written for the String Band.

The String Band’s woozy blend of myth, acid, memories of childhood, and Eastern music can be heard in a lot of English bands of the time. It wafts through the Stones’ psychedelic-period songs like “Dandelion” and “She’s a Rainbow.” To Led Zeppelin and T. Rex, the String Band were gurus of hippie Celticism who inspired those bands and others to season their rock and roll with mythic imagery and exotic instrumentation. “We just got the latest Incredible String Band record and followed the instructions,” was how Robert Plant explained Led Zeppelin III, which he and Page had cooked up in an old stone cottage in the Welsh countryside. To the Beatles, the String Band affirmed (and perhaps in part suggested) that notion of childhood recollection that first took form as “Penny Lane” b/w “Strawberry Fields Forever” and ultimately became Sgt. Pepper’s.

Valuing a child for being a child isn’t an obvious thing. In survival terms a child is a drag on the clan. It can’t fight, or defend itself, or hunt very well, or for that matter sow or reap. So valuing childlike traits implies that there are things that the community prizes as much or more than simple utility. It requires imagination almost a kind of spiritual mutation for humans to get to that point.

The idea is at least as old as the Gospel of Matthew, where Jesus says, “Unless you turn and become like children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven.” But it took the Romantic movement to make explicit the idea that children possess spiritual gifts that most adults lose as they grow older. William Wordsworth, for instance, received intimations of immortality from recollections of early childhood.

Not in entire forgetfulness,

And not in utter nakedness,

But trailing clouds of glory do we come

Shades of the prison-house begin to close

Upon the growing Boy,

But he beholds the light, and whence it flows,

He sees it in his joy;

At length the Man perceives it die away,

And fade into the light of common day.

“The child is father to the man” is a Romantic riddle that turns worldly hierarchy on its head. It means that the child is in some sense the superior of the man; the child is wiser than the man. Ironically, the eventual broad acceptance of this truth did not so much liberate the Victorian bourgeois as it haunted them and gave them a bad conscience. They sensed that the poets were right. In some part of themselves they had no doubt that children have access to worlds of experience that adults can no longer enter, and that it is good for the soul—even essential—to become as little children. And yet the world that nineteenth-century adults were feverishly building was in almost every way a brutal contradiction of that idea. It was a system that exalted above all else industry, utility, reason, practicality, the untrammeled pursuit of profits, and a global mercantile empire enforced by violence. The factory and the nursery were at odds, and the English were torn between them. Parents wanted to preserve the kingdom of childhood for their own children, and they were at the same time fearful and guilty that they might have destroyed it forever.

Beginning in the later part of Queen Victoria’s reign, this anxiety provoked a memorable response in the form of The Wind in the Willows, Peter Pan, Alice in Wonderland, Mary Poppins, The Water Babies, The Secret Garden, The Princess and the Goblin, Winnie the Pooh, The Railway Children, The Blue Fairy Book, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, A Book of Nonsense, Puck of Pook’s Hill, The Just So Stories, The Jungle Book, The Selfish Giant, The Hobbit, A Child’s Garden of Verses—among many, many others.

This literature opened up a new cultural space where the vision of childhood could be acknowledged, preserved, and even allowed to speak its upside-down wisdom, if—if—it was understood that the walls of the nursery were not to be finally breached, that the household in the end was not really to be turned upside down. This proved to be a hard boundary to police. The great thing about this literature is that by and large, it was not sentimental; there was a live core of subversion in it. The wonderful, dangerous life in these stories comes from the awareness that the wall was already arbitrary and permeable. This new realm of the child was in one sense a rebel hideout where the spirit of Romantic revolution, the spirit of the English secret history, survived in semisecret—the spirit of the smallest and weakest being the greatest, of the worthless things being the most valuable, where the adults are at a loss and the children are wise. A counterculture was tolerated in the nursery, on the shifting borderland between subversion and co-optation where most countercultures live.

The highly sophisticated, distinctly unusual adults who wrote these stories were very clearly writing to snare adult souls as much as to enthrall children. They made the case in book after book that it was crucial to the spiritual welfare of the adult to take a child’s consciousness seriously. In the intervening years we have lost much of the power of this insight to sentiment. From one angle these are simply the writers of the great bedtime stories, and the source of a lot of Disney movies. But from another they’re part of the stream of imaginative alternatives to modernity, capitalism, and world war that included decadents, Dadaists, occultists, and eventually beats and hippies.

The first generation of English rockers, born mostly during World War II, was the first to come fully of age after this literature had become solidly embedded in the English home. It’s even more of a common cultural link among them than their seemingly obligatory stints in public arts colleges.

Here’s Syd Barrett, the founder of Pink Floyd:

For all the time spent in that room

The doll’s house, darkness, old perfume

And fairy stories held me high

On clouds of sunlight floating by.

Oh Mother, tell me more

Syd Barrett, in “See Emily Play,” felt something irreducibly strange in the sight of a little girl playing alone in her garden. The song is an early Pink Floyd single, a piece of slightly cheesy acid pop, not at all like the polished productions that the aristocrats of the scene were crafting that same year. McCartney’s “Fixing a Hole” clearly doesn’t belong on Nuggets, but “Emily” does. David Bowie covered the song on Pin Ups because there’s a campiness to it, but the campiness has now gone through another cycle of taste into a kind of tatty elegance. Today it sounds as artificial and full of funny conventions as a crooner with a megaphone, but it has a kind of antique mystery because of it. And while the song is naïve compared to other music from 1967, you can go all the way through the Beatles and the Stones catalogs without feeling the frisson of early psychedelia like this. It is in its way the archetypal English psychedelic song, and from Emily’s haunted garden a woozy path extends to Strawberry Fields and Itchycoo Park. The image of the little girl playing by herself crystallizes the English acid sensibility. And the lords of the British secret history must have smiled to hear this Englishman conflate childhood freedom, acid freedom, and the old May Games, the games of the Man-Woman, the Hobby Horse, and Robin Hood.

As the Englishmen turn to the psychedelic, one also begins to hear their real accents, no longer the sort of mid-Atlantic, mutant R & B they’d been singing in. In fact, a kind of mincing over-pronounced Englishness, the sort that you can hear in the Small Faces “Here Come the Nice,” becomes almost a convention. Something in the way acid hit the English made the bands run to their old wardrobes and trundle out the Anglicisms that they might have downplayed before. “Show me that I’m everywhere / Then get me home for tea,” George Harrison asks at the start of his trip. In this way the English rockers added their own distinctive inflection to the English idea of childhood, an instantly recognizable blend of postwar lower-middle-class British boyhood with Neverland. So that these days, for instance, it’s hardly surprising that a lot of children go through a “Beatles phase,” that the music is as common in the “nurseries” of the twenty-first century as A Child’s Garden of Verses was in the twentieth: “Newspaper taxis appear on the shore, waiting to take you away.”

But the Incredible String Band went a step deeper.

We may no longer believe, like Victorian anthropologists, that in observing children we can learn something about the “childhood of the race.” And yet there is a connection between childhood and human beginnings, and the String Band’s music suggests it. It is one of the bigger insights of the sixties, an idea that was both conservative and radical—that, if you go back far enough in time, back to the beginning of any particular human thing, when the story might have gone one way or another, many of the things that would one day constitute society and culture were radically unstable. The most solid established things have their origin in wild magic. Nothing was fixed, everything was possible. Civilizations rest on a foundation of poems whose implications no longer startle, religions whose rituals have lost their drama, myths that the media have leached of meaning, visions that are safely mounted in museums. There was originally (and still is if you want to look for it) much greater freedom than we suppose. Society and culture come to seem very serious, but back there at the beginning is someone winking at you. This is the key to the British secret history. “When Adam delved and Eve span, who then was the gentleman?” sang Jack Straw and peasant rebels of Kent. This is the insight that British folk-rock is built on. It is how you can sing ancient songs and be revolutionaries.

And the theory of this vision says that each individual life reenacts the story: that your childhood holds the time when you were able to perceive clearly and act freely, when your eyes were open to the unspoken significance of things, and you were not so separate from the world. And, the theory goes, the secret of life is to cycle back through that original state, somehow, once in a while. This was part of the work of the British writers of children’s stories: to give grown-ups a chance to reconnect with the original vision, to periodically wash off the accretions of the years. And this is of course very close to what the first acid proselytizers believed they were offering. The notion that popular music could assist you in doing this was something that was either startlingly new in the 1960s, or something old that was coming around again.

Mike Heron and Robin Williamson were gifted but eccentric songwriters. Instead of statement-development-restatement, their idea of structure was a sort of a journey, wandering through fragments of what at first might sound like three or four distinct songs, before they arrive at any kind of resolution, which often comes in the form of a final song fragment. This structure—the suite-like song with multiple sub-songs connected perhaps thematically but not necessarily musically—actually became sort of a convention of late-sixties music (see, for example, “Happiness Is a Warm Gun”). There was, in fact, a sort of method to it—the writers knew that the mind couldn’t resist trying to make some kind of unity of it, and in doing so some kind of meaning would inevitably be created. And that the meaning arrived at in that way (so the thinking went) would be something as interesting as the song itself, would in fact be a part of that song even though the composers had had no idea of it.

And in fact, the patient listener to the Incredible String Band is rewarded by moments of strange loveliness, mad invention, or dark magic that do not exactly have a useful comparison elsewhere in pop music.

In 1968, with The Hangman’s Beautiful Daughter, the Incredible String Band reached escape velocity, breaking the last cobwebby ties with traditional folk and entering on one of those multi-album runs of inspiration that make late-sixties pop music feel so frenetically supercharged. The three albums that start here—The Hangman’s Beautiful Daughter, Wee Tam, and The Big Huge (or Wee Tam & The Big Huge when it was released as a double album in the United States)—are arguably the ne plus ultra of British psychedelia. With these records they added a frequency to the spectrum of the era that you would miss if it weren’t there, even if you’d never heard the Incredible String Band.

There was a wild sixties patina on the surface of the String Band’s music. It seemed experimental, far-out, very much of its moment. But there were long ages beneath. What connected the avant surface and the archaic depth was the notion that you had to get pretty far outside the boundaries of convention before you could see the golden chain that connected the whole human story, or at least all of human music. Inside the whimsy and eccentricity they believed they were creating a connection between those long ages behind us and the spooky electric future that was rushing in.

Here are some places where this actually seemed to happen.

“Witches Hat” from The Hangman’s Beautiful Daughter: “Certainly, the children have seen them, in quiet places where the moss grows green. . . .” An October fantasy that goes through the usual three or four changes in style, each adding a fragment to a child’s autumn dreaming, finishing with a Gypsy song and a tin whistle like the cold wind skirling across the end of the year.

“The Half-Remarkable Question,” from Wee Tam, a glimpse of eternity in rain on a windowpane leads to a curious reverie, with nods to the Kabbalah.

“Air” from Wee Tam, Mike imagines sex as the mingling of breath and bloodstreams in this hushed, tender song.

“Waltz of the New Moon,” from The Hangman’s Beautiful Daughter: a celebration of the orb that rules the night. Robin announces a new age in ancient symbols, stirring a maelstrom of mythic fragments as the ghosts of old Europe dance a crazy gavotte:

The new moon is rising

The axe of the thunder is broken

As never was

Not since the Flood

Nor yet since the world began

Many fans feel that the String Band’s high point is found in a series of long compositions of Robin’s (that grew steadily longer)—“Job’s Tears,” “Ducks on a Pond,” “Maya”—which saw the duo working further and further beyond the support of tradition, inventing their own lore. The climax was the sixteen-minute “Creation,” a peak of mad sixties syncretism and addled epic ambitions—an idiosyncratic, vaguely Near Eastern creation myth from a world similar to but not quite our own, accompanied by petal-strewing naiads.

Many other British bands of the sixties wandered into the mystic for a season and then swerved back out again. The British pop pattern was to start by playing R & B, get far-out for a year or two, then reconnect with the roots on a slightly more self-conscious level. Many of those bands made memorable music during their spell under the influence of psychedelia, but it wasn’t where they started and it wasn’t where they ended up. The String Band on the other hand, for better or worse, were dedicated to the fantastic. They weren’t just riffing on Tolkien tropes, they were actually fairly well versed in Western esotericism, and they understood the Celtic thing better than the rest. Which is why the String Band’s psychedelia was more sustainable and cut deeper than most of their peers. Besides one or two of their associates in Joe Boyd’s stable (like Fairport Convention), they were almost alone in entering the hot lights of sixties English pop from a deep folk background. They could take you places that blues-based rockers could not, and they could do it with an authority beyond the scope of your typical London rocker looking to take a pastoral break.

In the late sixties a theatrical aspect became increasingly important in the presentation of certain bands. Bands were often imagined as representing something larger than themselves—a region, a lifestyle, a subculture, some political or spiritual values. The cleverer bands made use of these projections, playing off them to add layers of extramusical meaning to their work. The Beatles were the best at this, probably because they had the strongest desires and hopes projected onto them. For many they represented a kind of psychedelic center amid the craziness of the time, the four of them together an icon of wholeness and benevolent wisdom. Though their individual songs were by no means always consistent with this image, the Beatles understood that Sgt. Pepper’s, to give the most obvious example, would be received in this context as a kind of summa of the acid vision, and that knowledge influenced the writing, recording, and sequencing of the album. In upstate New York, the Band carefully built a convincing group persona, choosing subject matter, recording style, album art, clothing, even facial hair, to evoke a mythic Great Depression America. Sometimes this process became actual theater, as when New Orleans session man Mac Rebennack took on the persona of Voodoo gris-gris man Dr. John, with elaborate costumes, choreography, and evocations of old New Orleans. The String Band performed mythopoeic Britain in a comparable way. On the cover of The Hangman’s Beautiful Daughter you see Robin, Mike, and their merry pranksters of the greenwoods, shaggy young men and their ladies, hippie gypsies in rags and blankets, suede and velvet, along with lots of strange, beautiful children. Seated casually onstage with their elfin girlfriends among their many instruments and carpets and flowers, the String Band in concert showed just how far things had gotten from the earnest self-presentation of folk. “We are songwriters and players and prophets from the North,” Robin would say, by way of introducing themselves to the Saxons south of the border.1 Williamson and Heron basically stayed in character through the late sixties. The giddy conviction they brought to their roles gave them a glamour that was a large part of what made them briefly the toast of the London scene. At the height of their success they talked Elektra into financing an elaborate theater piece, a sort of hermetic masque or acid pantomime they called U. To their fans, the String Band carried a world around with them, an unseen but implied society. They were ambassadors.

You could see why, in the immediate aftermath, it might have been tougher for the String Band than for a lot of their peers. They could hardly reconfigure themselves, like so many of their British peers, as blues-rockers and bludgeon their way into the seventies. For a few more awkward albums, they seemed like the last people at the masquerade, the only ones who didn’t have street clothes to change back into. The coach had turned back into a pumpkin. As the rock-and-roll audience landed back in ordinary time with adult lives to begin, and the transformation of the world kept getting postponed, some of the most fantastical promoters of the New Age for a time seemed like the biggest fools. Or con men. Some from the String Band’s former audience were perhaps a little surprised at what they had been lulled into.

But I think the worst we might say today of the Incredible String Band and their ilk out there on the furthest limbs of the sixties was that their festivity may have been a bit premature. The String Band were distilling essences from blossoms whose roots they and their fans had only begun to explore. It was a heady rush, but it finally needed more of a foundation than it had. Robin Williamson’s post-sixties career—one of the most creatively fertile of any of the era’s notables—has been in a way an effort to address that need. He has made himself into a master of creatively interpreted Celtic music, a scholar with a psychedelic twinkle still in his eye. He’s been busy excavating and laying foundations for the String Band’s visions in the soil of British tradition, to “give to airy nothing a local habitation and a name”—a foundation on which succeeding generations can again build cloud castles.

Robin’s signature keening sean-nos, among many other things, gave the String Band an intractable strangeness that has never been easily processed into nostalgia. Whether in Glasgow pubs or at the Fillmore East, they were content to be archetypal eccentrics. The world for a moment turned toward them, but Heron and Williamson wasted little effort chasing after it when it turned away again. It was their careless hippie chivalry, their happy and sort of noble agreement to forever be an acquired taste.

And this is consistent with the logic of the secret garden, because in the end the habitués of secret gardens know that there is something necessary about its being a secret. If the door wasn’t covered with ivy, if the old key wasn’t so hard to turn in the lock, if it wasn’t hard to follow the crying in the night—if it wasn’t a mystery—it wouldn’t work. Magic needs to be surrounded by a maze to keep its charge; it is finding the way that works the spell.

For grown-ups the path can seem to be nothing but perverse twists and turns—like an Incredible String Band song. But keep on “Round the corner. / Through the first gate, / Into our first world, . . .” to where “the leaves are full of children.” You’ll know it when you get there.