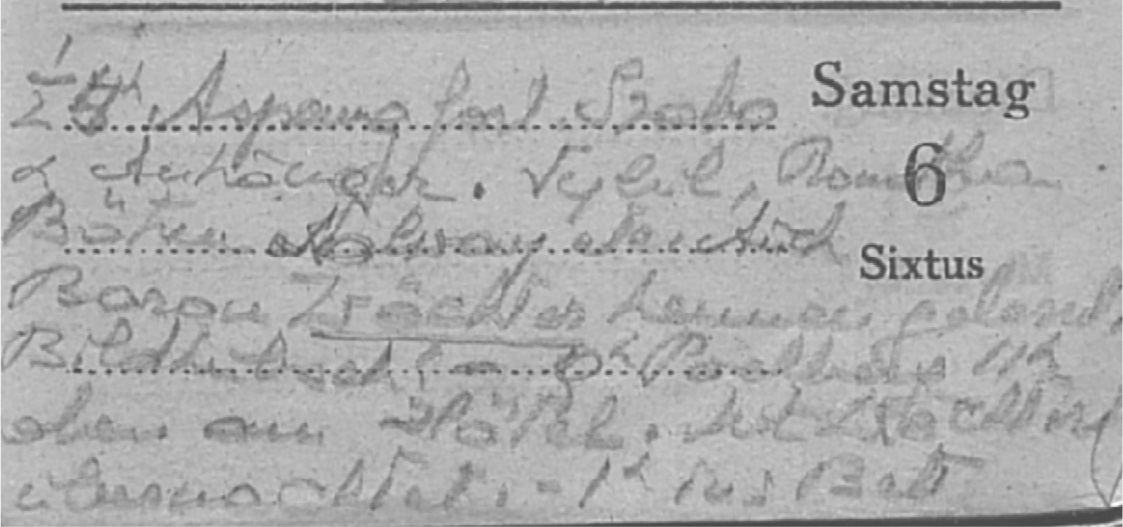

On the morning of Saturday, 6 April, Charlotte awoke in the family home on Belvederegasse. As the clock of the Catholic Church of St Elisabeth struck eight times, the telephone rang, a friend wondering if she’d like to spend a weekend on the Schneeberg, a nearby resort. An accomplished and competitive skier, she knew the mountain well, but the caller didn’t offer other attractions. Sensing her hesitation, he said they’d be joined by Herma Szabo, a world champion figure skater and Olympic gold medallist. Distantly related to Charlotte, Herma was always surrounded by attractive young men.

At the Südbahnhof, none of Herma’s eight male companions were of immediate interest to Charlotte, who decided to sit in a separate compartment of the train to Puchberg. Three good-looking young people entered, a girl and two men. ‘I particularly liked the tall, blond one,’ Charlotte recalled, but he was with a girl so she decided to ignore him. The tall, blond man was introduced to her as ‘Baron Wächter’, and she chatted amiably with Otto von Wächter, about matters of no importance.

By the time the train reached Puchberg, Charlotte learned the young woman was merely Otto’s sister Hertha, so she allowed an interest to be sparked. ‘My new “Baron” was tall, slender, athletic, with delicate features, very beautiful hands,’ she recorded. ‘He wore a diamond ring on the little finger of his right hand and had a noble appearance, one that any girl would notice.’ Charlotte ended up spending the weekend with the group, sharing a room with Hertha. They skied – she teased Otto when he waxed her skis, ‘what no gentleman had done before’ – and lunched at the Fischerhütte. With each hour Otto’s attractions grew.

They were joined by Emanuel – Manni – Braunegg, Otto’s closest friend at university, from whom she learned more about a national rowing champion who wanted to be an important lawyer. They returned together to Vienna. Otto promised to call, but as she didn’t trust him she took the precaution of obtaining his phone number. That evening, she wrote his name in her diary, and underlined it. Baron Wächter. Years later, she recalled, that was the day ‘I fell in love with good-looking, cheerful Otto’.

She offered no details about their conversations. Whether they talked about her art studies, or his political activities, his criminal conviction or membership of the Nazi Party in 1923, is not known.

Two weeks passed without contact, then Charlotte had a run-in with a horse-drawn carriage. The need for a lawyer offered a pretext to contact Otto, and he visited her the next day, at art school, to offer advice. They saw each other three weeks later, after she returned from a holiday in Italy. From Rome, on 4 May, she sent him a postcard of Castel Sant’Angelo, with the dome of St Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican visible in the background near the Santo Spirito Hospital. ‘I always keep my promises’, she wrote, ‘back on Monday’, but did not share another concern. ‘Who knows which girl would seduce Otto in the meantime?’ she recorded privately. The fear would last for many years.

Two weeks later they went dancing. Otto drove her home and tried to kiss her. She did not object, but the next day he apologised and asked: ‘By the way, do you want to marry me?’ She laughed and declined, not sure if he was serious, but also committed to her art studies and with no desire to become a dull housewife. Secretly she was thrilled. ‘How beautiful was our young and blossoming love, how happy I felt.’

She learned more about ambitious, joyful, jokey, flirtatious Otto. He was proud of his father Josef, sad about the unexpected death of his mother, from the prosperous, Viennese Pfob family. The family money was lost when Josef invested in war bonds at the end of the war, he told her, ‘for love of country’. Otto might come with a title but there would be no dowry.

During that long, first summer they spoke often, took walks in the City Park, visited the Prater, sat on benches on the Heldenplatz, boated in Tulln. On his twenty-eighth birthday she watched the ‘rowing rascal’ compete on the Danube, a minor celebrity who won competitions. She said nothing of Otto to her parents, as he was surrounded by other women, often flirting with them in her presence. He was, she noticed, unusually tactile and liked to hug and touch those around him, acts which planted a seed of jealousy that left deep roots. She sulked when he gave a rose to her friend Anita, so she kept other options open, responding to invitations, like the one from a stranger she met on a train. She even allowed Viktor Klarwill, known as Zybil, who she described as ein halb Juden (‘a half Jew’), to continue his futile pursuit of her.

That summer, she and her mother took a motoring holiday across Europe with Bishop Pawlikowski and his portly, middle-aged friend Monsignor Allmer, who liked to flirt with her. They drove across Switzerland, through France, to Spain. Lourdes left ‘a terrible impression’, hundreds of people on crutches in a procession to the main square. In Barcelona they attended the World Fair, drank moscato wines, enjoyed the Sagrada Familia, saw a bullfight at Castell de Mar, and visited the ‘romantic rock’ of Montserrat. At Figueres, Monsignor Allmer’s silly jokes caused Charlotte to wet herself.

Charlotte and Otto, who was canoeing on the Rhône, exchanged postcards and letters, all of which were kept. At the end of the summer Otto visited Mürzzuschlag, but the relationship remained a secret. ‘I was in love with him, but couldn’t show my feelings to my parents.’ Mutti, as Charlotte referred to her mother, would have been bowled over by the idea of a dashing baron. In the autumn, when school resumed, Charlotte drove Otto – ‘Tschaps’, she called him, a form of the English word ‘chap’ – from one courtroom hearing to another. He had little interest in opera or concerts, so they went to the cinema. Charlotte marked a success in the bar exams with a vase fashioned in clay, engraved with images of their activities.

At Christmas Otto skied in Kitzbühel, without her. She begged to join him but her father refused permission, so she stayed home, ‘very sad’. They talked each day by phone, one call lasting an hour and nine minutes, at huge cost.

Otto blew hot and cold as 1930 brought new suitors buzzing around Charlotte. In January they attended a ball, she magnificent in a yellow evening dress, crepe de Chine with little volantes. They danced so late into the night that she permitted herself to be hopeful, but then silence for three days. Another ball, a trip to the Schneeberg, a ski competition in the Altenmarkt. Otto turned his attentions towards Melita, a former flirt, and didn’t call Charlotte for days. ‘I never could be completely sure about him,’ Charlotte recalled. ‘His behaviour, hugging girls as soon as he met them, made me doubt again and again if he really was serious about me.’

In late spring things seemed to pick up. They took a hiking trip, up the mountain on foot, down with skis. One morning they left at four to climb to a mountain hut with memorable views over the Königsspitze. One avalanche after another, thundering noises, ‘unforgettable’, Charlotte recorded. Then up to the Schöntaufspitze, to 3,000 metres, where they hugged. Three hours up, ten minutes down, then to a castle with amazing views of Merano. An intimate night in Bolzano, but she did not give herself to him completely.

As the relationship progressed, more slowly than she wanted, Charlotte’s career began to take off. She set up an atelier at the family home, and her fabric designs started to sell (‘1,350 schillings in the first year, a lot for a beginner’). She took trips to Dresden and Hanover armed with books of drawings, which brought sales and flirtations, but she remained faithful to Otto.

In the autumn they took a three-week trip to Italy, without telling her parents, accompanied by Manni Braunegg, boats, a squashy air mattress and three tents. In Verona they attended a performance of Modest Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov, and on Lake Garda they slept in an olive grove near Sirmione. ‘Beautiful signorinas’ buzzed around Otto, causing her to wonder if she would ever get used to the attention he drew. In Venice they spent a night at a hotel on the Grand Canal, their skins so darkened by olive oil that someone described them as I Negri, ‘the Negroes’. ‘The best holiday of my life’, she recalled, ‘totally carefree and full of young love’.

In Vienna, Charlotte fell ill with jaundice. Otto visited; she hoped for a proposal of marriage but it didn’t come. No interest in marrying a rich girl, he told her. Christmas brought new hope. ‘I truly belonged to him, and loved him more than anything’, a man who could enforce his will on her. ‘I liked that’, and that he was right in everything he said.

It was around this time that Otto rejoined the Nazi Party. His membership number was 301,097.

The year 1931 was dominated by the death of Charlotte’s beloved grandfather, Dr Scheindler, the school inspector, from pneumonia. Only to him did she confide the secret of her love for Otto and the hope of marriage. ‘Marry and bear 10 children,’ her grandfather advised her.

Life fell into a routine. Art school, slalom competitions on the Schneeberg, evenings with old friends, encounters with new ones, like the Fischböcks, Hans and Trudl. Otto’s persistent interest in other women, like her wealthy cousin Paula – small, blonde, ‘nigger lips’, who would irritate Charlotte for another four decades – continued to jar. Charlotte got rid of Paula by outskiing her, and she outclimbed all the other competition, literally: on one occasion, she and Otto took four hours to reach the peak of the Zuckerhütl, 3,505 metres of sugarloaf, using only a rope and two pickaxes.

In March 1931, in keeping with the times and his interests, Charlotte offered Otto a gift, a copy of Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf. Black cover, no title, a gilded eagle astride a swastika. ‘Through struggle and love,’ she wrote on the flyleaf, ‘to the finish.’ Many years later, the book hid on a shelf in Horst’s castle, and I would pick it out at random. ‘I didn’t know I had that!’ Horst chuckled, excitedly. He had lost the copy given to him by his godfather, Arthur Seyss-Inquart.

Two months after the gift, Charlotte joined the party. That was 28 May 1931, member number 510,379. Her diary rarely referenced Otto’s political activities, and made no mention of his Nazi membership, or that he had risen to the upper echelons of its Viennese chapter. As district chief of the Nazi Party in Vienna, he followed his father into the Deutsche Klub, becoming a member of the board in January 1932. Here he met members who would play a significant role in his life, like the writer Franz Hieronymus Riedl, lawyers Hans Fischböck, Arthur Seyss-Inquart and Ernst Kaltenbrunner, and Hanns Blaschke, future mayor of Vienna. Wilhelm Höttl and Charlotte’s brother Heinrich Bleckmann also became members of the Klub, which offered lectures and concerts at its offices in the Hofburg. In January 1931, Hans Frank visited from Germany to deliver a special lecture, well attended because he worked as a lawyer for Adolf Hitler. The Klub became a hub for plotting and intrigue by Austrian Nazis.

That summer, Otto spent five weeks in Munich at the Reichsführerschule, a summer school for aspiring Nazis. ‘I’m ever so busy’, he wrote to Charlotte, ‘elected as the scribe’ to a group of ninety Nazis bonded by a ‘wonderful feeling of camaraderie’. The day was divided in military fashion – ‘waking, morning gymnastics, bathing, breakfast, lecture 1, lecture 2 etc., eating, etc.’ – with singing and games at night, exercises and marches during the day. ‘The whole thing is very interesting and informative – we’re listening to the big names in the party, even Hitler spoke to us, it was wonderful.’

He returned with photographs to be pasted into the family album, the one that Horst showed me on that first visit. The album did not, however, include a copy of a famous photograph, one that I came across elsewhere, of the participants at the summer school. Taken by Heinrich Hoffmann, Hitler’s photographer, Otto stood in the second row, just to the left of Hitler.

‘Tschapsli telephoned again after five weeks,’ Charlotte recorded in her diary, which also noted political developments: two weeks after he returned she scribbled ‘Heimwehr putsch’ into the diary, a reference to an abortive coup attempt by a nationalist group. Many of its members would, in due course, join Otto in the National Socialists.

In September she spent time in Mürzzuschlag, working on fabric designs, enjoying the mountains and receiving visitors. Everything was ‘so lovely’ away from Vienna, ‘all those Jews, wherever you go – they make me completely despair’. If her radicalism developed any further, she warned Otto, she’d ‘soon be going around with a dagger’. One visitor was Alfred Frauenfeld, recently appointed as Nazi Gauleiter in Vienna, who offered to introduce her to Hitler and accompany her on her travels. ‘You always say that England is very important and that we should direct as much propaganda there as here,’ she told Otto. Frauenfeld raised her self-confidence, which he’d ‘beaten down’, she implied, teasingly. ‘All I hear on Bräunerstrasse is how silly and ugly I am, with a Jewish nose and small feet, too fat, etc.’

In October, she travelled to England to sell fabric samples. The journey allowed a conversation with a Frenchman, in which she argued for an Anschluss – ‘joining’ – with Germany. A union between Germany and France was impossible, she told him, and talk of international cooperation was ‘a Jewish ploy’. Delighted to be back in London, she attended a concert at the Austrian embassy and celebrated her birthday with brother Heini, the local representative of the family steel mill. In Manchester she was introduced to Mr Caswell of the Calico Printers’ Association, who purchased samples for a decent sum, fell in love with her, and invited her to Paris. She declined, as he was married with two sons.

The visit coincided with a general election campaign in the United Kingdom, and her own political awakening. She welcomed the mood, a country where most firms refused to buy foreign steel, even Heini’s. ‘You can breathe easily in a country where the inhabitants almost to a man have such a nationalistic feeling,’ she wrote to Otto, although they’d failed adequately to ‘emphasise the Jewish question’. Many she met were open to ideas about national socialism, so she ‘spread the word’.

The British election was won by a National Government, led by the Conservatives, with support from Labour and Liberal politicians. ‘Everyone believes in a better future thanks to nationalism,’ she informed Otto, on 28 October. Hopefully the Germans would follow suit, set aside their differences, and ‘join hands under the flag that A. Hitler will hoist’. Those who believed such ideas were impractical should travel to England. A week later she planned her return to Austria, via Munich. ‘You could pick me up from there, my love, and tie it in with your visit to Hitler.’

The trip to Britain was a success, and with the money earned – over 10,000 schillings – she was able to buy a small house with a garden at number 5 Anzengrubergasse, on a hill at Klosterneuburg Weidling, a Viennese suburb with fine views over the Danube. It served as a studio and a place to host events, like a children’s party at which she offered gifts ‘under the sign of the swastika’. National Socialism was now a full part of daily life. In the diary she noted a meeting attended with Otto, inscribed with a swastika that danced across the page.

The following year, 1932, opened with no proposal of marriage. Charlotte travelled across Germany and then back to England to sell more fabric designs. Otto completed his training and set up a law office of his own, with Dr Georg Freiherr von Ettingshausen, a friend and comrade in the party, at 47 Margarethenstrasse, in Vienna’s 4th district. Otto practised mostly in commercial law, and in the first month earned 8,000 schillings, which compared favourably with the 14,000 schillings Charlotte earned in the previous year. His cases were varied, and included an appearance before the Regional Court of Vienna in a copyright case. He acted for the photographer Lothar Rübelt, who claimed infringement of his rights by the writer Karl Kraus, for the unauthorised publication in Die Fackel, the satirical magazine, of a Rübelt photograph of Baron Alfons von Rothschild.

He also had another line of work, offering legal advice to party members in difficulty, and to the party itself, which chimed with his political engagement. In April 1932 he joined the Schutzstaffel – the SS – the paramilitary force created as an elite bodyguard unit for Adolf Hitler, as SS member 235,368. As a member of the Verband deutsch-arischer Rechtsanwälte Österreichs (Association of German-Aryan Lawyers of Austria), he spent ever more time at the Deutsche Klub, from where Charlotte would often collect him.

In the spring they took a boating holiday, and in June sailed on the Neusiedler See. Charlotte returned to England in the summer, where she met brother Heini’s rich, beautiful girlfriend, whose father refused to let his daughter marry an Austrian. In Dublin, with her mother and Bishop Pawlikowski, she attended the thirty-first International Eucharistic Congress, held in Phoenix Park, to celebrate the 1,500th anniversary of St Patrick’s arrival in Ireland.

Back in Vienna, on 8 July they celebrated Otto’s birthday at his small apartment, with wine, schnapps and love. After three and a half years of ‘persistent and tenacious restraint’, unable to resist, she offered herself to him completely. That night, as she put it, she revealed to him ‘the biggest secret’.

With no offer of marriage, Charlotte’s doubts rose. She worried about his closed and cautious character, the shy disposition, the ‘childlike’ way he conducted himself. He was ambitious and unable to show his feelings; she loved him.

A month later, after a canoe trip, she started to feel unwell. After a doctor told her she was pregnant, she broke the news to Otto in a small café on Margarethenstrasse, near his office. He did not offer to marry her, and she spent the evening alone, weeping.

Two days later Otto relented, under pressure from Manni Braunegg. He wanted a quick marriage, and offered her his late mother’s wedding ring. They travelled to Mürzzuschlag to tell her parents, who consented instantly. Proud to have a baron as a son-in-law, Mutti made no enquiries as to the haste. A day later the couple visited General Josef Wächter at the Hotel Straubingher, in Bad Gastein, where he was taking the waters. He almost toppled over on hearing the news, Charlotte recalled, then hugged her tight. He too consented.

The wedding took place on Sunday, 11 September, in the Basilica of Mariazell. Bishop Pawlikowski officiated, Manni Braunegg and Charlotte’s brother Heini acted as witnesses. Few guests were invited, barely enough to make it an event, as Otto wanted a discreet ceremony. She wore a traditional Styrian dirndl dress, to hide the pregnancy; he donned a bespoke Styrian suit. ‘I could not wait for the ceremony to end, as a fly sat on my arm, itching,’ Charlotte recalled.

A feast followed, and the newlyweds spent the night at a small inn near Leopoldstein. The next morning they returned early to Vienna, as Otto had a court hearing. Whether it concerned a commercial matter, or representation of the party, Charlotte did not record.