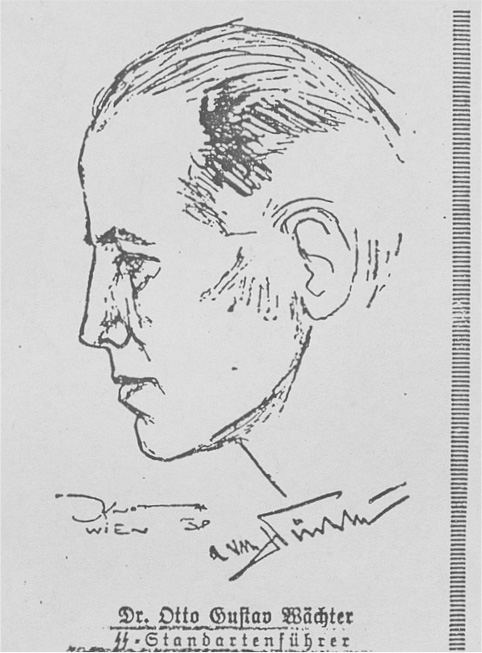

Otto’s job as a state secretary offered power and perks, an office in the Hofburg, and a portrait in the Völkischer Beobachter, the leading Nazi daily. The Wächters were provided with a new Mercedes and home, following the sale of the recently acquired property in Berlin and Charlotte’s house in Klosterneuburg. In July they moved into the Villa Mendl, an official residence made available with the help of Georg Lippert, a friend, architect and recent convert to the Nazi cause. The property came with a park of its own, at 11 Wallmodengasse, in Vienna’s plush 19th district, appropriated from the Mendl family, founders of the renowned Ankerbrot bakery.

There wasn’t much on the market but Lippert ‘obtained the Jewess Bettina Mendl’s house for us’, was how Charlotte put it. Bettina Mendl, educated at Cheltenham Ladies’ College, ran the business founded by her father. As a passionate anti-Nazi and fine equestrian, she had refused to compete at the 1936 Berlin Olympics. She fled Vienna as German troops arrived and ended up in Sydney, Australia. A memoir by her daughter explained that Lippert was one of Bettina’s closest friends, a frequent visitor to the villa, where he played tennis and attended concerts and parties. He curried favour with the Nazis, and arranged for the property to be requisitioned and ‘become the residence of Dr (Baron) Gustav Otto Wächter’. In the daughter’s account, the Wächters looted the Mendl family’s treasures, including a fine collection of art and antique crystal glassware. ‘In the years after World War II, attempts were made to bring Wächter to justice for war crimes,’ she continued, but the efforts failed, as he ‘used the loot from Villa Mendl and other similar properties to purchase safe custody’.

Villa Mendl was no doubt ‘very beautiful’, but Charlotte complained it was in poor condition – only one wing habitable – and too ‘old-fashioned, cold and uncomfortable’ for her taste. Yet she appreciated the vast living room and fine library, and a veranda that overlooked the elegant gardens, where she could entertain. She retained the Baumgartners as caretakers (‘good old sorts’ who quickly transferred their loyalties), hired a nanny for the children (a gem, ‘soft, warm and plump’), and had a cook.

At the Villa Mendl, in October, Charlotte celebrated her thirtieth birthday, an occasion marked with ten roses from Arthur Seyss-Inquart. The month was filled with concerts and films, Don Carlos at the Vienna State Opera, Under the Roofs of Paris at the cinema, and the Chancellor of Tyrol at the Josefstadt Theatre. In the company of the Seyss-Inquarts, she was introduced to Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, on a visit from Berlin.

Otto’s work brought travel around the Reich and Europe. In September he and Charlotte went to Nuremberg, and spent four days at the Tenth National Socialist Party Congress, a ‘Rally for Greater Germany’. Three quarters of a million people attended, the largest such gathering but also the last. In her diary Charlotte noted the daily themes: ‘Friday 9th, in honour of political leaders; Sunday 11th, celebration of the S.A.; Monday 12th, eulogy for the Wehrmacht’. On the final day, Hitler spoke to the joy of the Anschluss, a welcome for his Austrian ‘fighters’. He declared: ‘Today you stand among us, as Volksgenossen and citizens of the German Reich’, after a lengthy period of suffering caused by the nefarious Versailles Treaty, victims of the duplicity of the ‘democracies’ and the Bolsheviks in Moscow, and of the Jewish parasites who sucked the lifeblood out of Germany. Charlotte placed a photograph into the family album, a night shot.

A few days later she noted the Sudetenland crisis. ‘Chamberlain with Führer’, she wrote, ‘scary situation’. Seyss-Inquart assured her that war would be avoided, but she took the precaution of buying gas masks for the family.

Otto’s long working hours, and the fear that he was once again engaged in extramarital dalliances, caused Charlotte’s mood to plummet. On 8 November, she bought a picture and had a ghastly, upset evening alone. On the 9th, she went to Otto’s office to confront him, describing her own behaviour as ‘nasty’. In the evening she attended the premiere of Cromwell at the Burgtheater, a new play to celebrate ‘strong leadership in the service of a united nation’. If, on leaving the theatre, she noticed the events of Kristallnacht on the streets of Vienna, they passed without mention in the diary. Party members roamed Vienna, ransacked Jewish businesses, destroyed synagogues, beat up Jews and then arrested them.

The next morning she returned to Otto’s office. ‘I was cross and nasty, again,’ she recorded of the renewed confrontation. Back in the villa at noon, she spent the day waiting for him to come home. They spent a ‘fearful’ evening together. Within a week, however, her spirits improved and calm was restored. She attended a concert of Mozart and Beethoven, conducted by Furtwängler, and a performance of Die Fledermaus. New Year’s Eve was spent at the Volkstheater, at the Opernball. ‘Afterwards home and waited for midnight alone’, she recorded. Still, 1938 was a ‘glamorous year which brought big changes to our lives! … We are now a big country, and we have the Führer.’

Otto’s work took him ever more deeply into the heart of Nazi power. He travelled frequently to Berlin, often with Seyss-Inquart, or his colleague Walter Rafelsberger who, by the end of 1938, had Aryanised and seized more than 26,000 Jewish small and medium-sized enterprises.

As state secretary, Otto’s office was in the Ballhaus, and the family album held several photographs. ‘Back in Vienna!’ he wrote on the back of one. Interior shots, a stairway, the Congress Hall, a portrait of Otto in the Neue Freie Presse, views of his office and Seyss-Inquart’s, a large map of Ostmark, a meeting room, a waiting room. ‘View from my room, in the Viennese spring’, he wrote on another. His work was assisted by fresh legislation imported from Germany. Within a week of the Anschluss, a new constitutional provision allowed for the reform of public bodies. A special ordinance restructured the Austrian civil service, a Berufsbeamtenverordnung, or ‘BBV’, which empowered Otto to remove any civil servant from his position. Section 3 operated more or less automatically, to dismiss all Jews and Mischlinge, part Jews. Section 4 gave Otto the power to dismiss or ‘retire’ others, because of ‘prior political behaviour’ that might undermine the Nazi cause. Otto’s decisions were final, without appeal to any court.

He was empowered to remove vast numbers of public officials from their posts, because they were Jewish or politically unreliable. Decisions were recorded in correspondence and other documents, carefully archived. I was not able to find a single example of his use of an exception in the legislation, or any act of leniency. Examples of the individuals he targeted were not hard to find. He removed Viktor Kraft, a teacher of philosophy and chief state librarian of the University of Vienna, from his positions because he had a Jewish wife and was once a member of the Wiener Kreis (Vienna Circle). Friedrich König was another target in the university library, a volunteer with the imperial army who lost a leg and an eye. On 5 June 1939 Otto wrote to inform him he had lost his job. ‘Because you are a Mischling, First Grade,’ he wrote.

The precise number of individuals subjected to Otto’s Säuberungsaktion (‘cleansing action’), as his work was known, was difficult to ascertain, as many of the files sent to Berlin were lost. On the basis of archives in Vienna, however, it seems that Otto dismissed or reprimanded at least 16,237 civil servants, 5,963 of whom were classified as ‘high ranking’. The numbers included 238 working in the federal chancellery, 3,600 in the security service, 1,035 in the judicial sector, 2,281 in the educational sector, 651 from the financial sector, and 1,497 from the postal service.

Otto’s ‘cleansing actions’ were implemented with single-minded purpose, and had significant consequences. ‘A number of times I tried to put in a good word for my old comrades with Wächter,’ a senior colleague reported, ‘but succeeded only very rarely.’ Those who ‘were hit or brushed by Wächter’s sword couldn’t even get a job on the side’. In some cases Otto’s actions had fatal consequences. He wrote to the 64-year-old former procurator-general, Robert Winterstein, who had served as minister of justice in von Schuschnigg’s government: ‘In light of § 4 para. 3 of the Ordinance on the Restructuring of the Austrian Civil Service of 31 May 1938, RGBl.I S.607 you are dismissed. Your dismissal enters into force on the day this notice is delivered. The dismissal cannot be appealed. Signed: Wächter.’ The former minister was arrested on Kristallnacht, as Charlotte attended the Burgtheater. Deported to the Buchenwald concentration camp, he was dead within eighteen months.

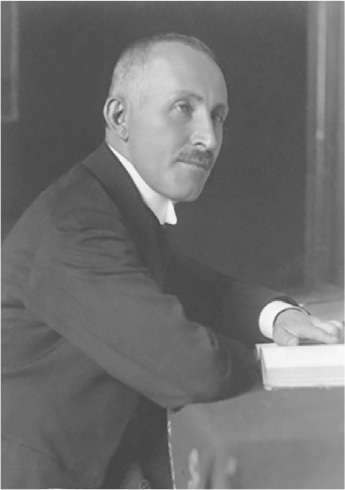

Otto even targeted some of his former teachers at the law faculty of Vienna University. Professor Josef Hupka, for example, on the left, who taught him trade and exchange law, and signed his university graduation certificate, was one victim. Professor Stephan Brassloff, who lectured him in three courses, including Roman criminal law, was another. Removed from their university positions in the summer of 1938, within six months both lost their pension rights. In due course both professors would be deported to camps, where they perished.

The task of cleansing the Austrian civil service – only a ‘temporary position’, Seyss-Inquart indicated – was not without challenges. ‘I remember Otto being very unhappy in this job,’ Charlotte recalled, although the diaries written contemporaneously offered no hint of unhappiness. He was forced ‘to “clean” the civil service of the people who weren’t Nazis or were against the Nazis’, she told photographer Lothar Rübelt. In other words, to paraphrase her thinking, he had to purge, didn’t really want to.

Still, she recognised the position did allow him to give full expression to his love of politics, even if it gave rise to intrigue and, when things went wrong, blame. Otto was ‘stuck’ in the job and often got into ‘hot water’. ‘The Nazis said he wasn’t tough or thorough enough, the opposition complained he was too strict!’ He became ill, his teeth rotted. A dentist recommended the removal of ten teeth, another offered a less draconian solution, root canal treatment. Such were the travails faced by Otto Wächter.

Then, unexpectedly, Seyss-Inquart was replaced as governor of Ostmark by Josef Bürckel. ‘A German, from the Palatinate’, Charlotte recorded, small, fat, rude, a drinker, with no hint of sensitivity or tact. Otto wanted out, and the arrival of war saved him. In August 1939, Germany and the Soviet Union signed the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, with a secret protocol to divide Europe into ‘spheres of influence’. On the morning of Friday, 1 September, Germany found a pretext to attack Poland, causing Britain and France to declare war, to Charlotte’s great disappointment. Two weeks later, as the Red Army moved into Poland from the east, Germany and the Soviet Union agreed to divide Poland and create a new frontier.

On 8 October Hitler annexed large parts of western Poland, with a view to making them part of the Greater German Reich. A few days later, he declared the establishment of a Government General to run parts of German-occupied Poland, naming Dr Hans Frank as his personal representative, the governor general. Arthur Seyss-Inquart was appointed as deputy, and Josef Bühler as state secretary, the number three. The territory of German-occupied Poland was divided into four districts – Kraków, Lublin, Radom and Warsaw – each with a governor who reported to Hitler and Dr Frank.

On 17 October, on the recommendation of Seyss-Inquart, Otto was appointed chief administrator for the District of Kraków. He was delighted, as was Charlotte. ‘Full of joy to change posts, hoping to get a better task’, she recorded.

He did not have to wait long for the better task.