CHAPTER TWO

The Hyperpower

TWO FULL DAYS ELAPSED AFTER NAPOLEON’S SURRENDER AT WATERLOO before Major Henry Percy, one of Wellington’s attachés, careened through a wildly cheering crowd in a post-chaise and four, dashed into a London ball, and knelt before the Prince Regent, announcing “Victory! Sir! Victory!” Legend has it that Nathan Rothschild made a fortune by trading on the advance notice brought by his carrier pigeon networks from Europe. It’s almost true. Rothschild’s couriers—they weren’t pigeons—did get him early word of the victory. But Rothschild didn’t quite make a killing; instead, he prevented a total family disaster by unloading part of the bullion mountain he’d amassed in expectation of a prolonged war.

1

The victory at Waterloo, and the American treaty ratified just months before, left England finally at peace and in surprisingly good financial shape. British growth in the period 1800–1830, if slow by late-nineteenth-century standards, was markedly faster than in any previous period. Despite the immense financial drains of the late wars, Great Britain still had a surplus of capital and was exporting capital to the world. The Rothschilds and the Barings rode that wave to new pinnacles of finance. As Byron put it in

Don Juan:

Who keep the world, both old and new, in pain Or pleasure? Who makes politics run glibber all? The shade of Buonaparte’s noble daring?— Jew Rothschild, and his fellow Christian Baring.2

The sources of the growth are not readily explicable by changes in standard inputs like labor and capital, which suggests that much of it was driven by new technology. In other words, “Ingenuity, not accumulation, drove economic growth in this period.”

3

A Very British Industrial Revolution

In his famous account of the pin factory in the

Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith explained how the division of labor so greatly increased labor output: “One man draws out the wire, another straights it, a third cuts it, a fourth points it, [etc. through eighteen steps].... Each person, therefore, making a tenth part of forty-eight thousand pins, might be considered as making four thousand eight hundred pins in a day. But if they had all wrought separately and independently, and without any of them have been educated to this peculiar business, they certainly could not each of them have made twenty, perhaps not one pin in a day.”

4 Smith gives the impression that this is a firsthand account, but sharp-eyed scholars noticed that it matched, process for process, the description of a French pin factory in Diderot’s

Encyclopédie. The dead giveaway is that in Smith’s factory the workers were still making pins by hand, while contemporary English factories were water-powered. British plants used far fewer workers than their French counterparts, and the work was laid out to accommodate the mechanization. Although the French plant cited by Diderot was next to a river, it did not even have a waterwheel.

The French preference for manual over mechanized processes was not irrational. Labor was very cheap in France, and capital was scarce, so pins were best made by people. In Great Britain, it was labor that was expensive, while capital was readily available and energy, in the form of coal, was very cheap. That’s the reason a profit-driven British pin maker chose to use a big, and quite inefficient, Newcomen steam engine to recirculate his water to steady its flow rate, and by extension, that’s why the Industrial Revolution happened in Great Britain and not in France.

5 But that just shifts the question: Why was British labor expensive?

In 1500, about three-quarters of the populations of most European countries, including Great Britain, worked in agriculture. The most advanced trading countries, Netherlands and Belgium, were more urbanized than most, as to a lesser extent were Italy and Spain. By 1800, however, Great Britain had only about a third of its population in agriculture, far less than any other state, with the remainder either urbanized or working in rural industries.

Large-scale social changes were obviously afoot. Here is one plausible narrative: The Black Death (mid to late 1300s) depopulated England’s countryside, freeing much high quality land for pasture. With better forage, the quality of English wool improved markedly, and England’s wool trade expanded, displacing Flemish and Italian cloth. Cottage-based weaving grew apace, along with related manufacturing—spinning wheels, containers, wagons, and ships. Port cities invested heavily in harbors and dockyards, while trade deepened banking, insurance, and other services, which increased the returns from literacy and numeracy. Crucially, as their forests shrank, Britons learned how to use coal as their primary energy source, a process that took a full century.

As talented people were drawn to the cities and into business, agricultural markets expanded, pressuring agricultural productivity. Town records show common-field smallholders actively experimenting with plant varieties and crop rotation schemes to improve output. A British empirical, scientific style of thinking became a norm. And wages rose. By 1800, British wages, measured by both exchange rates and purchasing power, were the highest in Europe by a wide margin. Processes that moved at a glacial creep in the sixteenth century, coalesced and accreted in the seventeenth, and finally exploded in the eighteenth.

j6Cotton textile manufacture was the quintessential industry of the British Industrial Revolution. From a small cottage enterprise in the early 1700s, it had grown by 1830 to employ 425,000 workers, accounting for one out of every six manufacturing jobs and about 8 percent of GDP. But the burst of mechanical development that created the world’s first mass-production factories was preceded by seventy-five years of diligent tinkering.

7Yarn spinning is a quintessentially hand-labor task. Cotton fibers are delicate. To use in cloth, they first must be cleaned and straightened; then a “spinster,” using the traditional spinning wheel, would repeatedly draw the fibers out under finger pressure while twisting them for strength. Drawing up machinery to replicate hand-spinning was relatively straightforward, but actually building machines that could manipulate the threads more or less as humans did, and without breaking them, took years of trial-and-error experiment. The first successful spinning machine was the jenny, built in 1767 and driven by a hand crank. James Hargreaves, a weaver, worked out a method of holding the rough cotton, or roving, with pins, while a bar stretched out and twisted the fibers. It worked well enough that an early demonstration provoked a riot by the local hand-spinners. But by the 1780s, many cottage hand-spinners were using twelve-and twenty-four-spindle jennies. A twelve-spindle jenny cost about seventy times as much as a spinning wheel, so the productivity pickup must have been very high.

Richard Arkwright was right behind with the water frame, a spinning machine designed to be water-powered. Arkwright was more entrepreneur than inventor, and he was determined to create a cotton mill industry. He bought patents and hired craftsmen to come up with the machinery. His water frame applied rolling technology similar to that used in glass and metal working. The rovings were fed into three successive rollers: the first compressed them, while the second two, each running at progressively higher speeds, both compressed and stretched the fibers as another device twisted them. Arkwright was far from the first inventor to try rollers: the challenge was getting the speeds, the pressures, and the spacing between the rollers right. Arkwright also had the insight to hire clockmakers to build his machines, for they had the most contemporary experience with precision gearing.

The foot-treadle, flying shuttle, heddle loom achieved very high manual production rates. At each push of the treadle, the heddles raised and lowered alternate warp (long) threads, creating a shed to pass the weft (cross) thread through, and the batten pushed the new weft thread firmly into place. The flying shuttle allowed the operator to remain seated and very rapidly pull the weft threads back and forth through the alternating sheds. Mechanized looms worked exactly the same way, but at much higher rates of speed.

By roughly the same methods, Arkwright produced the first successful “carding” machine—for combing out the raw cotton—and then spent most of a decade trying to build a cotton mill. Cotton mill management was a new discipline: it required learning how to run banks of the new machines efficiently, how to lay out the work flow, and how to manage machined cotton. The stages from machined rovings to finished yarns were subtly different from those of hand-spun cotton. Knowing what machine speeds to apply with different fibers and spotting when a yarn was about to break, knowing how to intervene and how to restart equipment after a disaster—in effect, the basic textbook of mill management—had to be invented from scratch. Arkwright’s second major mill got most of it right and was the prototype for a new British industry.

Mechanization in the textile industry was an alternating race between spinning and weaving. The fly-shuttle foot-pedal heddle loom was a highly rationalized machine that quickly pressured the capacity of the hand-spinning industry, forcing the pace of mechanization. Mechanized spinning shifted the pressure back to weaving. The fly-shuttle loom almost cried out for mechanization; the challenge lay in tuning the pressures on the threads to produce acceptable cloth while minimizing breakage, the way a skilled human did by feel.

It was much the same with the steam engine. Galileo’s pupil Evangelista Torricelli did much of the early basic science, and a Frenchman, Denis Papin, constructed early working models. The first useful industrial-scale steam engine was built by Thomas Newcomen in 1712 to lift water out of a tin mine—flooding of underground mines was a chronic problem. It used a vacuum to produce work. Steam entered a cylinder and raised a piston; a jet of water cooled the cylinder, and the steam condensed, causing the piston to fall, and thereby lift water.

Very little is known about Newcomen, except that it took him at least ten years to work out his concepts, and he was forced to share his patent with businessmen who bought a master patent on all “fire-engines” from the estate of Thomas Savery, who had failed to develop a working engine. But Newcomen’s invention is a marvel. Instead of trying to lift water directly by the piston, he used it to drive an oscillating pump handle—the walking beam engine. All prior engine models required an attendant to change valve settings at each stroke, but Newcomen operated his valves from the beam motions, possibly the first self-acting engine. His method of piston sealing was standard for many years. Newcomen-type engines spread rapidly through the British and European mining industry, although their inventor may have earned little from them.

Newcomen-type engines reigned for a half century, until James Watt engineered another design leap. Watt was an instrument maker who was asked to build a model engine for teaching purposes at the University of Edinburgh. As he worked on it, it occurred to him that the engine’s use of fuel was prodigious relative to its output, and he calculated that three-quarters of the fuel was spent reheating the cylinder after it had been cooled to create a vacuum. That was not a problem at coal mines, where fuel was almost a free good, but it limited the engine’s potential usefulness elsewhere. Watt’s solution was to create a separate condenser with an air pump: when the steam entered the cylinder, the air pump created a vacuum in the condenser; the steam then rushed to the condenser, and the piston fell, with only minimal change in the piston-cylinder temperature. The resulting engine was more complicated but far more efficient, and it would operate at low steam pressures, simplifying boiler construction.

The Newcomen engine used atmospheric pressure to do work. The right side of the walking beam (large wooden horizontal piece at top) acted as a pump handle that raised water as it was pushed down. In the starting position for a new stroke, the “pump handle” was tilted up by the weight of the pump rod on left. (The beam in the picture is shown in mid-stroke.) The work sequence was: 1) Steam fills piston cylinder. 2) Jet of cold water sprays outside of cylinder, condensing the steam and creating a vacuum. 3) The weight of the atmosphere pushes pump handle down and lifts water. 4) Weight of the pump rod returns handle to initial position. Stroke rates were about twelve per minute; boiler technology limited pressures to only one or two pounds per square inch.

Watt did little with his engine until he partnered with Matthew Boulton in 1774. Boulton was a small metal product manufacturer and an honest man who convinced Watts that he had a global business opportunity. With Boulton in charge of the business side, and Watt steadily improving his designs, the partnership sold hundreds of engines throughout Great Britain and abroad. Boulton and Watt both retired when their patents expired in 1800, turning over the business to their capable sons. Over the rest of the nineteenth century, Boulton & Watt–type engines were gradually supplanted by lighter and less expensive high-pressure engines, developed independently by Richard Trevithick in Great Britain and Oliver Evans in the United States. Boulton & Watt–style engines kept a foothold well into the nineteenth century, wherever safety and fuel efficiency were dominant concerns, as in transatlantic steam ships.

8By much the same processes, the British also came to dominate in iron and steel, although the critical innovations were powered by dire necessity. Iron and steel were among the most ancient of products, and in the first part of the eighteenth century, the Germans, Swiss, and French all vied for leadership. The British pulled ahead by the century’s end, even though they started from a huge disadvantage. Iron processing requires vast amounts of fuel, traditionally charcoal, almost always used in direct contact with the ore or metal. By the eighteenth century, however, the British industry was close to exhausting its wood supplies and was forced to fall back on coal, which is high in impurities that can be fatal to iron quality. The process of overcoming that obstacle made the British industry by far the most technically sophisticated in the world. Key developments were the use of coke, a purified form of coal,

k as a charcoal substitute; the development of the reverberatory furnace, which melted iron without direct contact with the fuel; and the puddling process, a deeply skilled craft using long poles to stir melted iron from a reverberatory furnace to create quality wrought iron. Very little of this qualified as new invention; it was instead accomplished by focused and sustained development of older technologies.

British iron prowess allowed the great machinist John Wilkinson to cast solid naval cannons and bore their holes—a formidable challenge. Other countries cast their cannon in molds, but they tended to explode. (Recall Isaac Chauncey’s cannon debacle during the Burlington Races on Ontario.) A French expert reported to his government in 1775 that it had been twenty years since a British naval cannon had exploded, while French sailors “fear the guns they are serving more than those of the enemy.”

9The crown jewel of British metallurgy was “crucible steel,” which was brought to a high state of perfection by Benjamin Huntsman in the 1740s near Sheffield, traditionally the British center for high-end steelmaking. Huntsman was trying to make very durable, very hard, very thin steel for clock and watch springs. The method he finally hit on entailed remelting quality conventional steel in clay “crucibles” or pots. The resulting product was a steel that was easily poured and cast and took a superb edge. Foreign competitors found the best Sheffield steel almost impossible to replicate. (The secret of the process, deduced only much later, was the local clay used in the pots.) A Swiss reported in 1778 that “the cast steel of England is, without contradiction, the most beautiful steel in commerce; it is the hardest, the most compact, and the most homogeneous; one can recognize it at a glance.”

10The advances fed off each other. Lighter, more efficient steam engines were the perfect power source for textile factories, blast-furnace blowers, and the lathes, forges, trip-hammers, and other essential apparatus of big-ticket manufacturing. Bigger factories meant bigger machines running at higher speeds and tighter tolerances. High-speed engines impelled deeper inquiries into the physics and chemistries of metals and fuels, which fed into the knowledge base for soap production, bleaches, etching acids, and gas lighting for 24/7 factories. Sometime in the late eighteenth century, the British achieved a point of critical mass at which understanding expanded exponentially, and inventions, technologies, and accumulating lore cohered into an irresistible surge.

The long evolution brought forth a new culture. Or perhaps it was the other way round. The great-grandfather of the British empiricist tradition, after all, was a Briton: William of Ockham, a medieval monk. Whatever the reason, the British were different from other Europeans. The eager emigrants fleeing to the American colonies may have viewed their mother country as stifling and class-ridden, but no other established nation was as free and democratic or gave as much scope to the individual. Great Britain was nominally ruled by a languid upper class, but unlike a country like France or Italy, it allowed room for energetic climbers in the middle; indeed, the top strata admitted the most successful strivers to their own ranks. Joseph Whitworth came from a middle-class family but was made a baronet in recognition of his great contributions to British technology.

England was commercial to its toes. Money talked—even dominated the conversation. Contracts were honored, patents generally respected. The country was empirical, swayed by what worked, disposed to clinch an argument with numbers. Its banking and monetary practices were the best in the world, its currency reliable. Honor was paid to the new and the better. The powers that be were more willing than elsewhere to disrupt old rhythms and break old patterns. Turnpikes, canals, and then railroads proliferated sooner than anywhere else. In short, Great Britain was the perfect petri dish for the viruses of industrial revolution, the benign and the noxious alike.

11All complex developments are in some degree path-dependent. Early choices and random cornerings may dominate outcomes far down the road. Because of the importance of the navy to national survival, a powerful stream of British technology was driven by naval priorities, which imparted a particular twist toward the ultraprecise. A century later, that bias, perhaps interacting with a certain upper-class intellectual style, may have disadvantaged Great Britain in its inevitable industrial confrontation with the United States.

The Longitude Problem

Eighteenth-century British admirals grumbled about keeping their ships out past August. The navigational apparatus for taking latitude readings—the north/south position—was quite accurate. The noon sighting—to fix the latitude, recalibrate the ship’s clock, and turn the calendar—was inviolable ritual on British warships. A captain could readily find a line on the same latitude as the mouth of the English Channel and ride it home. Without obvious landmarks, however, it was much harder to divine how far east or west you were. That was the longitude problem, and to a seafaring nation it was of first importance. Without accurate longitude readings, ships could lose all sense of location in open oceans. Even when familiar trade routes were known to harbor pirates, merchants dared not vary from them for fear of getting lost. Muddled positioning extended voyages far beyond expectations: men got scurvy; missing a small island with fresh water could be a death sentence.

Almost all voyages home were by way of the Channel, so making the entrance was a routine but dangerous part of any sea captain’s job. The Channel entrance is wide: the distance from the Isles of Scilly off the south coast of Cornwall to Ushant in Brittany is about 120 miles. It is an area of swirling currents and treacherous, relatively featureless rocky coasts, and the setting for Alfred Hitchcock’s Jamaica Inn, in which locals live off the pickings from shipwrecks and sometimes engineer the wrecks. In fog or other difficult weather, any captain could lose his bearings.

A military convoy returning home in 1704 mistook the looming Cornwall coast for Guernsey, which is off Brittany. Believing they were in the channel, they turned north and sailed some sixty miles up the Atlantic coast before realizing their mistake. More tragically, in 1707, a returning war fleet, under the impression they were well into the channel mouth, made the turn north and ran directly on the rocks of the Scillies, losing four warships, a popular admiral, and 2,000 crewmen. The shock led to the passage of the Longitude Act, which offered a series of prizes for full or partial solutions to the challenge of accurately positioning a ship at sea on the east-west axis.

12There were two potential solutions. One involved time. If you set a clock at Greenwich time before leaving England, you could accurately calculate longitude simply by taking the difference between Greenwich time and sun time at your location. But the clock had to be extremely accurate, off by less than three seconds a day. If the Greenwich time readings drifted by even very modest amounts, they would add up to disablingly large variations over the weeks or months of a typical sea voyage. Just as challenging, the clock would need to be utterly impervious to the extremities of a sailing-era sea voyage: the sharp temperature changes, the storm batterings, the salt everywhere. In 1721, no less an authority than Isaac Newton declared that it would be all but impossible for a solution to the longitude problem to come from the “Watchmakers.”

The “Astronomical” solution, which Newton preferred, was at least as difficult. Sailors long ago learned to fix latitudes because the apparent path of the sun was so readily observed and easily measured. The so-called fixed stars also had a regular apparent path around the earth, but it was far too slow to be useful. Then there was the moon, which does have a regular pattern but an extremely complicated one that varies with the seasons, local variations in the earth’s magnetic fields, and much else. In principle, however, it was possible to precisely chart the moon’s position with reference to the fixed stars. If you looked up the moon’s position in a moon chart, it would tell you the exact time that pattern occurred over Greenwich. If you also knew your local time, you could calculate, again in principle, your east-west position.

13In principle. But observational instruments were not nearly accurate enough to track anything but the grossest positional changes of the moon with reference to the fixed stars. Even if they had the requisite accuracy, it would be very difficult to take such readings from the deck of a rolling ship. There were also some nasty mathematical complications to correct both your position and the reading from Greenwich to that of an observer at the center of the earth.

Newton, for once, was wrong, and the watchmakers won. A self-taught genius named John Harrison built four candidate clocks over thirty years. They were highly innovative but extremely complex, and there were serious questions about their reproducibility. Nevertheless, all of them met the requirements for the prize, although it took the intervention of the king to secure Harrison his award, in part because of opposition from the astronomers who dominated the awards committee.

lIn the event, roughly a quarter century after Harrison’s death in 1777, watchmakers in both France and England were turning out affordable and reliable pocket-sized marine chronometers that enabled longitudinal calculations satisfactory for most purposes. Only a few of Harrison’s innovations were retained. Most chronometer makers chose to stick with traditional forms and mechanisms but learned how to execute them at new orders of precision.

The astronomers got there too, by dint of an informal fifty-year international collaboration to build the necessary tables of lunar motion, along with the development of the sextant, the first instrument with the precision required for useful positional readings on the stars. The great Swiss mathematician Leonard Euler contributed practical methods for correcting the data, but they still took an expert some four hours of calculation. Their practicality, that is, was hardly better than that of Harrison’s strange instruments. But the lunar charts were maintained and promulgated, and the correction math simplified, so by the first decades of the nineteenth century the two approaches were coexisting comfortably, with practical navigators frequently checking one against the other.

It is a remarkable episode. A century elapsed between the 1707 Scilly Isles tragedy and achievement of a stable solution, but it was pursued consistently and diligently over that entire span. Although there was an international flavor to the longitude project throughout, it was driven primarily by the British.

Its lasting stamp on British technology was something of an obsession for absolute mechanical precision, or what British machinists came to call “the truth.”

The Quest for Truth

Until well into the nineteenth century, machinists’ tools typically lacked graduated measurement markings. In fact it was hard to do. All draftsmen knew how to make accurate divisions by geometric methods, using a compass and square edge, but beyond fairly crude resolutions, any method of marking by hand was apt to be greatly inaccurate. The solution was leverage. Releasing a pin could drop a trip-hammer: a small motion was converted into a much larger one. But leverage could be reversed, and a gross movement converted into a much finer one. And that was the path of truth.

14The illustrations on pages 52–53 show various methods of achieving greater precision from imprecise measuring tools, most commonly by exploiting the leverage gained from screws and gears. Assume a tool or workpiece held by a chuck that is moved by a screw with twenty threads to the inch. Rotate the screw one full rotation, and the chuck advances by a twentieth of an inch. A gear train with a net twenty-to-one gear-tooth ratio would accomplish the same result. Such solutions are easy to envision, but they just relocate the problem—from making accurate measurements to making accurate screw threads and gear teeth. Clockmakers had small machines for cutting gear teeth early in the eighteenth century, but they weren’t especially precise. Individual prodigies like John Harrison could work marvels of precision by hand, but that was not a solution either. The challenge was to embed the required level of precision in machinery that could make other machines, so those machines could pass on their precision to generations of new tools and instruments. That took the better part of a hundred years.

Why did it take so long? Because as a practical matter, it is not possible to make an accurate screw thread without an accurate screw-cutting lathe, which is impossible to make without tools with accurate screw threads. In other words, accuracy could be achieved only by a process of successive approximation. And that is a tedious path, with many byways, involving better metals, better bearings, even better magnifying lenses. The work took place primarily in England because naval and other high-end engineering applications had created a market for high-precision scientific instruments for astronomy, surveying, and a host of industrial uses. Brilliant scientists in other countries were not as successful. For example, a French nobleman, the Duc de Chaulnes, made several important advances in gear-cutting machinery, but he was working with his own money and lacked the thick network of machine users, designers, and craftsmen that existed in England.

Jesse Ramsden usually gets credit for inventing the first industrial-scale dividing engine. It didn’t cut the gear teeth but marked their placement, which was the essential task. “Inventing,” in this context, is not quite the right word, for all such machines were developments of others’ work. Several important features of the Ramsden dividing engine, like screw-based motion controls, were inspired by predecessors like de Chaulnes, as Ramsden freely acknowledged. One of his best-known instruments representing “the best design of the time”

15 (from the late 1780s) was a large theodolite, or surveying telescope, which fixes locations by taking the intersection of horizontal and vertical circles. Measurements were read from verniers (see illustration) and viewed through microscopes. Ramsden built two of the instruments, which were used for a complete survey of Great Britain. At a distance of ten miles, the instrument was accurate to one arc second, or about three inches.

A. Astronomer Tycho Brahe (1546–1601) popularizes the use of linear transversals to achieve greater precision. If the marks on the two axes at the limits of the day’s technlogy for acurate gradiation, simply making the grid and drawing the transversals as shown improves the accuracy by a factor of ten. The heavy vertical line intersects at the. 04horizontal mark. B. By yhe eighteenth century astronomers learned to improve astral measurements with are transversals. The numbered ring is marked in 5-degree intervals. The six inner concentrics subdivide to an accuracy of 50 minutes. The right-hand heavy line from the origin intersects at the 150-minute mark, so the angle measures 5 degrees plus 150 minutes = 7,5 degrees. C. The Vernier Caliper uses a second sliding rule to mark out very small distances. In the example, the caliper marking is beyond the.30 position on the fixed scale. The additional distance is read from the vernier scale at the point where it lines up most closely with a marking on the fixed scale, as shown. 5Humans are very good at recognizing when two moving lines line up—"vernier acuity.")

D. Using geometrics mehods, an artisan could mark reasonably-accurate divisions on a large disc, and then capture those same proportions on a much smaler workpiece, as shown. Note that the index wheel includes several choices of toothh arrangemenr and that the index pointer fixes the index wheel and the workpiece in position for each cut. E. A pocket-sized thousandth of an inch micrometer first appeared in the catalog of the Providence firm of brown and Sharpe in 1877, and marked a high point of convenient recision in the nineteenth century. The micrometers are still in wide use. The numbered divisions on the barrel signify tenths (0.1) of an inch. Each smaller division is a fortieth (0.025) of an inch, while each small numbered marking on the handle is a thousandth (0.001) of inch In the illustration the readout on the barrel is 0.125 inches, plus an additional .001 on the handle = 0.126 inches.

The great figure in screw threads was Henry Maudslay, one of the greatest machinists of all time. Although he ran a large establishment in his later years, he was at heart a shop-floor machinist. He also appears to be have been a man of immense calm and good humor, certainly comfortably fat in his later years. His workers adored him, almost as much as they admired his technical skills. One recounted fondly, “It was a pleasure to see him handle a tool of any kind, but he was quite splendid with an eighteen-inch file.”

16 Maudslay’s permanent contribution was to stabilize machining at very high levels of precision, hardly surpassed to the present day.

When Maudslay began his career, screw threads were in a state of disarray with respect to pitch (thread count), shape, angle, and uniformity, and they became his pet project. While he did not invent the modern screw-cutting lathe—Ramsden anticipated much of his work—his first versions achieved such a high pitch of perfection that they became the standard for all such instruments.

In a traditional lathe, the worker held the cutting tool against the rotating workpiece. In the Maudslay screw-cutting lathe, first produced between 1797 and 1800, before he was thirty, the workpiece was positioned on a slide by a long lead screw, the cutting depth of the tool was set by a screw-driven micrometer, and a gear-set controlled the thread count of the new screw by varying the speed of the workpiece rotation relative to its lateral motion on the slide. Different gear settings allowed reliable production of a variety of thread pitches. The gearing on one early machine accommodated twenty-eight different thread pitches. One Maudslay-produced screw, created for a dividing engine to be used in the production of large astronomical instruments, was five feet long and two inches in diameter, with 50 threads per inch, or 3,000 threads in all; it came with a foot-long nut with 600 threads. No one before Maudslay could have produced such an instrument.

Maudslay’s obsession with accuracy pervaded every aspect of his machinery, since vibrations, misalignments, or slightly loose fittings make a mockery of ultraprecise tool settings. Maudslay’s constructions set new standards for solidity, stability, and perfection with respect to planes, angles, and uniformity of motion. He built a bench micrometer to measure deviances of a workpiece from a pattern to a ten-thousandth of an inch. He called it the “Lord Chancellor,” the final arbiter of any dispute.

Maudslay also insisted on absolutely flat, smooth planes on every surface, and every machinist in his shop was equipped with a plate that met that standard. His famous protégé, James Nasmyth, wrote that they were used to test “the surfaces of slide valves, or wherever absolute true plane surfaces were essential to the attainment of the best results.” When absolutely true surfaces were placed on each other, Nasmyth went on, they “would float upon the thin stratum of air between them until dislodged.... When they adhered closely to each other they could only be separated by sliding each off each.”

17The method of creating perfect planes was to start with three plates machined as perfectly flat as they could be. One plate, Plate A, was then coated with a colored powder, and Plate B placed precisely on it. When the two plates were separated, the color marks on B would mark its high spots relative to A. B was then scraped by a very hard hand scraper (both machine and hand grinding were far too coarse) to remove the anomalies. The process was then reversed—coloring B and scraping the discrepancies from A—and repeated as often as necessary until each plate color-matched across its entire surface. But a perfect match between two plates did not yet prove a perfect plane, because they might embody complementary deviances. Therefore the whole process was repeated twice more, first matching A to C and then C to B, at which point, one could be confident that the three approached “absolute truth.”

With some ingenuity, the method may be extended to produce perfect right angles and perfectly parallel rectangular bars with perfectly aligned plane ends. (Hint: each of those processes requires

four plates and

two bars.) A nineteenth-century textbook warns merely that “the only thing to be dreaded is the discovery of a hollow portion, which may compel a repetition of the procedure from the commencement.”

18Maudslay protégés dominated the British tool industry for decades. Nasmyth invented the steam hammer in 1838. It operated on the same principle as a drop hammer: a giant hammerhead fell on a forging target. The difference was that the steam hammer’s blow was piston-driven for an even more powerful impact. Nasmyth’s hammer weighed two and a half tons but was under such precise control that it could rattle a whole factory or break an egg in a wine glass without disturbing the glass.

19Of all the Maudslay disciples, the greatest may have been Sir Joseph Whitworth, who unified British screw designs under the “Whitworth standard,” specifying radii, pitches, angles, and depths that for many years served as nearly a world standard. He also carried the quest for absolute mechanical precision about as far as it could go before the age of electronics.

The Millionth-of-an-Inch Measuring Machine

Sir Joseph’s portrait shows him long-faced, heavy-lidded, and skeptical. His father was a minister and schoolmaster, so he was better educated than most craftsmen and did not easily tolerate fools. Pompously ignorant officialdom was among his particular bêtes noires. As a leading machinery and metals fabricator, Whitworth was necessarily a force in armament procurement. A rigorous experimenter and prolific inventor, he produced a great flood of weapons designs and experimental new weapons, which were routinely rejected by the military authorities, although a number were later quietly adopted. Those misadventures are documented in a coldly sarcastic little book he published in 1873, when he was seventy.

20Whitworth was prompted to develop his measuring machine by the mid-century bumblings of a parliamentary Committee on Standards, which labored for eleven years to create a bar equal in length to a standard yard. The stumbling blocks lay in the physics of ordinary materials at microscopic dimensions. Tiny increases in ambient temperatures changed the length of a bar, the minutest forces caused nearly undetectable sags or flexes, and so forth.

But the committee painstakingly worked its way through all such obstacles to the point where the stage was set for the climactic measurements. Ambient temperature was controlled by a thermometer accurate to within 1/100°F. The bar itself was suspended in a tub of mercury to equalize ambient pressures, while the tub was shielded within a tank of water to muffle the slightest external disturbances. The readings were taken by microscopes on platforms at each end of the suspended bar.

21There was no difficulty in producing an initial standard bar—a yard, after all, was whatever the bar said it was. The challenge was to produce

additional bars of exactly the same length—enough to be distributed among the universities and science establishments to serve as the reference point for high-precision undertakings of all kinds. The Royal Astronomical Society, an unofficial kibitzer in chief, expected that standard bars should be executed in the primary metal types—“copper, brass, cast-iron, Low-Moor iron, Swedish iron and cast steel.”

22With the elaborate arrangements all in place, the great day finally came. The committee duly selected one bar, “bronze 28,” as the standard, and proceeded to measure six other bars against it. That there were differences was no surprise: everyone agreed that “bronze 19” was not exactly the same length as bronze 28. The surprise was that committee members differed on whether it was longer or shorter, although the observations had been made sequentially under completely identical conditions. Disconcerted, the committee recruited volunteer observers, all men with professional backgrounds in related fields. Some 200,000 measurements later, the committee reluctantly concluded that no consensus could be reached on any of the bars. The differences, moreover, were not random: some individuals were consistently on the short side, others consistently on the long.

Whitworth’s reaction was a jeering

of course! The measurements were taken by comparing the position of a cross-hair in the microscope with a tiny etched gradation on the bar. But the crosshair, a mere spider-silk to the naked eye, was magnified to a thick, fuzzy, line that, in the blurring vision of a committeeman, danced from one side to the other of an equally gross and irregular gradation line. The Astronomical Society put the best face on it, remarking that the uncertainties were “not likely to affect any useful observation” and that “a limit seems to be shown which, in any

optical measures, no amount of observation in our current state of knowledge can overpass.”

23Whitworth thought it all surpassing idiocy. The committee’s measurements seemed to randomize at resolutions of about 1/30,000 of an inch. His own workshops frequently worked at tolerances of 1/50,000 of an inch, and most experienced machinists could accurately distinguish differences of 1/10,000 of an inch by feel.

m Where the committee had gone astray, he argued in multiple venues, was in attempting visual assessments of length as opposed to merely determining the

difference between two bars, which could be done mechanically with great precision. Given any standard bar with perfect plane ends, Whitworth claimed, he could determine the difference between it and any other like it at resolutions of a millionth of an inch, which he then proceeded to demonstrate. (Maudslay’s micrometer measured to the ten-thousandth of an inch, a hundred times larger.)

The measuring machine Whitworth constructed to fulfill his boast comprised two parallel steel bars resting on a heavy cast-iron stand—the bars, the stand, and their respective borings all corrected to near-absolute truth. The working portion of the machine was a grip made by two opposed, perfectly trued small circular plugs. One of the plugs was driven by a leadscrew with a pitch of 20 threads to the inch; that screw was driven by a wheel with 200 teeth; that wheel in turn was driven by a “division wheel” with 250 marked divisions: 250 × 200 × 20 = 1,000,000. Turning the division wheel by one notch advanced or withdrew the plug by 1/1,000,000 of an inch. Equivalently, a 1/1,000,000 of an inch movement in the lead screw generated a visible movement of about .04 inches in the division wheel, a 40,000:1 magnification.

Whitworth’s famous measuring machine was designed to measure the difference between two apparently identical objects to the millionth of an inch. It takes 200 turns of the 250-division “division wheel” to turn both the 200-tooth rear wheel and the interior lead screw one full turn. Twenty full turns of the lead screw will advance the plug by a full inch—250 × 200 × 20 = 1,000,000. The bottom drawing shows the placement of the “feeling piece,” a very thin sliver of metal with the shape as shown. The experimenter placed the first piece in the machine with the feeling piece, then gently relaxed the pressure until the feeling piece moved, and noted that place on the division wheel. He repeated the procedure for the second piece and compared the two markings.

The measuring procedure was straightforward. You fixed the standard bar in the grip with a precisely crafted “feeling piece,” an extremely thin sliver of steel. Whitworth stipulated a detailed protocol for inserting the feeling piece. You then slowly turned the division wheel, relaxing the pressure until the feeling piece moved, and you noted the mark on the division wheel. Repeat the process with a second bar, and the same feeling piece would expose any differences in length to a resolution of 1/1,000,000 of an inch. There was no ambiguity: when the feeling piece moved, you took the measurement and compared it to the same measurement for the standard bar. Whitworth’s measuring machine was awarded the gold medal at the Great Crystal Palace Exhibition of 1851.

nThe Whitworth measuring machine was a pinnacle of nineteenth-century British precision engineering: a line of development rooted in the urgent search for precision in chronometers and astronomical apparatus, one that ran through the nearly perfect machine tools turned out by Henry Maudslay and the exquisite precision of the Nasmyth steam hammer. But the somewhat defensive comment by the Royal Astronomical Society that such precision was “not likely to affect any useful observation” was true, at least in a machine setting. Even today, ultraprecision computerized machine tools work at precisions of a few hundred thousandths of an inch.

Whitworth’s measuring machine still pales beside the most audacious grasp at ultraprecise complexity. The ne plus ultra of regal overreaching was Charles Babbage’s calculating engines.

Charles Babbage

If there were a hall of fame of intelligent people, Charles Babbage (1791–1871) would surely have his own plaque. Born into a well-to-do family, he spent most of his career in academia and for a dozen years held the Lucasian Chair of Mathematics at Cambridge University, a post graced by luminaries from Isaac Newton through Stephen Hawking.

24In Babbage’s day, all calculation-intensive sciences like astronomy were dependent on thick volumes of standard tables—logarithms, sines, and other functions—each incorporating decades of laborious construction. As a newly minted mathematician, Babbage realized that even the best tables were riddled with errors. By comparing entries in different editions, it was clear that the primary problem lay in transcription and typesetting, not the original calculations. He therefore conceived of a machine, the Difference Engine,

o to infallibly compute and print such tables.

By 1822, Babbage had constructed a mechanical calculator that very rapidly executed standard arithmetic operations up to eight figures. He demonstrated it at the Treasury, and proposed that the government finance a much larger machine that would calculate and print any regularly sequenced table. With the Royal Society’s backing, the following year, the Treasury provided a grant of £1,500. By his own account, Babbage undertook to complete the project “in two, or at most three, years,” with a commitment of his own funds of £1,500–£2,500.

25To execute the new machine, Babbage contracted with Joseph Clement, another former protégé of Maudslay. Clement is best-known for his large-scale metal planing machine, built sometime before 1832. The machine, with a planing bed that could hold work up to six feet square, moved on rollers so precise that “if you put a piece of paper under one of the rollers, it would stop all the rest.” For more than a decade, there was no other planer of its size in the world, so Clement, who charged by the square foot, made an excellent living keeping it operating almost around the clock. His partially completed Difference Engine has been called “the most refined and intricate piece of mechanism constructed up to that time.”

26 Whitworth was one of the journeyman machinists employed by Clement on the engine.

Babbage had seriously underestimated the work involved and by 1827 had expended not only the grant amount, but beyond the estimated limit of his own funds. His version of what ensued shows him as a brilliant but almost comically contentious man. He duly applied for further assistance, but as a matter of right, on the grounds that the government had committed to see the project through, which seems a strained interpretation of the record.

p But he was backed by powerful friends and the Royal Society. Even the Duke of Wellington, then prime minister, became personally involved. Another £1,500 was awarded in early 1829, and yet another £3,000 later that same year, which Babbage at first refused to accept absent a firm open-ended financial commitment.

27Babbage had Clement construct a working segment of the Difference Engine in 1832 that, impressively, could produce a portion of the promised tables, and the government had already financed the construction of a small fireproof building to house it. By then, however, Babbage and Clement were constantly clashing over finances, and in 1833, Clement finally resigned, taking his machinery.

Amid the confusion, Babbage shifted his focus to an entirely new idea, which he called the “Analytical Engine.” It was nothing less than a prototype of the modern computer executed with purely mechanical parts. Delighted and inspired by the concept, Babbage worked on it alone for several years before admitting to the government that he was making a completely new start. Not surprisingly, ministers threw up their hands. Stubbornly, Babbage worked on the Analytical Engine for the next decade, using his own dwindling resources. To stretch his finances, he retired to a modest house with his own workshop and forge and a few assistants.

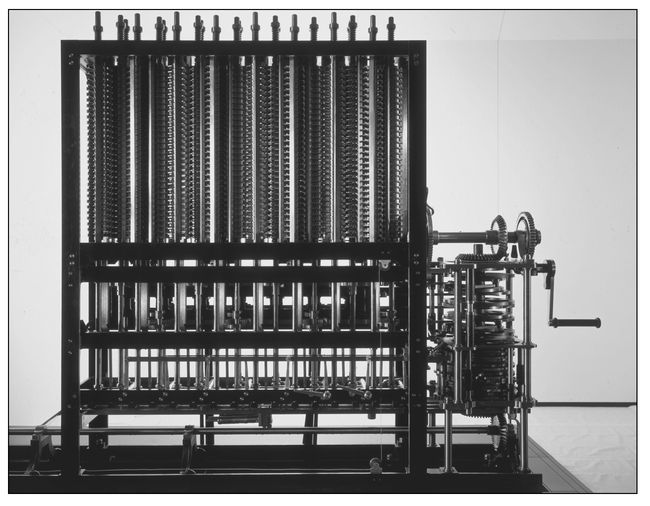

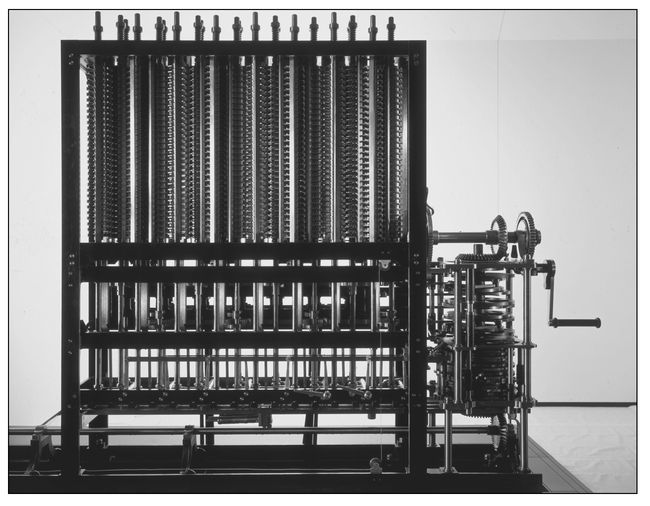

In about 1843, apparently realizing that the government was never going to finance his Analytical Engine, Babbage decided on a different strategy: redesigning his original Difference Engine to take advantage of the new streamlined architecture of the Analytical Engine. He began to work on a “Difference Engine No. 2,” in 1846, producing a completely executed set of plans by 1849. This was by far the most practicable of his inventions: a limited-purpose Analytical Engine optimized to execute the mathematical tables proposed for the first Difference Engine. The proposed apparatus would have been much more efficient than the original, with only a third as many parts. Still, since the final product would have consisted of a wall of some 8,000 whirling parts, it would have been a substantial challenge.

To Babbage’s shock and disappointment, the new government, which had come to office on an austerity platform, would not even entertain the idea of another prolonged engagement with Babbage: “Mr. Babbage’s projects appear to be so indefinitely expensive, the ultimate success so problematical, and the ultimate expenditure so large and so utterly incapable of being calculated, that the government would not be justified in taking upon itself any further liability.”

28 For Babbage, the cold rejection of his new plan was a serious blow that embittered much of his later life. He continued to produce books and articles on an array of subjects, wistfully tinkering with the design of the analytical engine until his death in 1871.

But the design is still an intellectual monument. Babbage’s inspiration was from the Jacquard loom, which used punch cards to signify any pattern of threads whatsoever. Experts rendered patterns in sequences of punch cards. The textile mill then created additional sequences of cards to specify the thread colors for the pattern.

The Analytical Engine similarly had two main components, the mill and the store. A set of operation cards, similar to IBM punch cards, defined the sequence of operations to be performed by the mill, while a second set of variable cards summoned the sequence of data to be manipulated. Other sets of cards loaded the variables and constants into the store and defined where the results of an operation were to be stored. Output could either be printed or used to impress casts for printer’s type.

The machine’s registers—a small brass wheel for each digit—would accommodate fifty-digit numbers, which Babbage thought sufficient for science, along with 1,000 stored constants. Sequences of cards were placed in a card reader and called on in the proper order, and all standard operations would be maintained in libraries of cards. (Babbage also worked out a provision for an unlimited number of if-then, “looped” instructions.) Gear layouts and speeds were such that the engine should have been able to perform about sixty operations a minute.

29Babbage topped it off with another invention, his “Mechanical Notation”—a language for specifying rigorously any machine whatsoever (or, in Babbage’s mind, almost anything at all, including physiology, factory organization, or war planning).

30 It is a detailed coding system for machine parts, actions, and motions that, as he explained to the Royal Society in 1826, reflected the actual machine with such precision “that at any moment of time in the course of the cycle of operations of any machine, we may know the state of motion or rest of any particular part.”

31Babbage told the Society that he had been compelled to develop the notation as he grappled with the complex gear sequences of the Difference Engine. Once a machine was completely rendered in notation, one could readily see whether the design would work or not, and how to simplify and improve it, without the expense of building a model. Once he had described the Difference Engine in notation, Babbage claimed, he could spot design issues much faster than the artisans. The Society presentation was illustrated by a notational description of an eight-day clock. Comprising four oversized pages of dense columns of cryptic markings, it is a beautiful and astonishing production, rather like a Japanese archival scroll. The drawings, notebooks, and other documentation for the nearly completed design of the Analytical Engine comprise nearly 7,000 pages, of which 2,200 are purely notation.

32Babbage thought the notation was “one of the most important contributions I have made to human knowledge. It has placed the construction of machinery in the ranks of demonstrative science. The day will arrive when no school of mechanical drawing will be thought complete without teaching it.”

33 Once again, however, Babbage was pointing directly to developments still far in the future. It was only with the onset of the postwar Computer Age that technologists began to execute their chip and other hardware designs in software so they could be tested and exercised without the expense of building physical components.

And It Worked

The tantalizing historical question for Babbage admirers was always whether his machines would actually have worked. That was finally answered by an extraordinary project at the London Science Museum that built a working model of the Difference Engine No. 2 (DE2 hereafter). And yes, it actually worked.

The DE2 was the redesigned Difference Engine No. 1 using the new architecture Babbage had created for his Analytical Engine. It was the smallest of Babbage’s engines and the only one with a completed design, which happened to be stored, along with its Mechanical Notation, in the museum’s archives. Alan Bromley, a computer scientist at the University of Sydney, made a study of the plans over a number of years and convinced himself, and then the museum staff and directors, that it was feasible to build and would probably work as Babbage claimed.

34The project got underway in 1985, under the direction of Doron Swade, then the Science Museum’s head of collections and an expert on Babbage and the history of computing, working on a tight six-year schedule, timed to the Babbage bicentennial in 1991. The final construct was seven feet high, eleven feet across, and eighteen inches deep. It had eight tall columns, each with thirty-one figure wheels, all of it operated by a hand crank. A few drawings had to be reconstructed, and Babbage’s designs also included a small number of mistakes—this was, after all, a purely paper design, with no testing of individual modules—but they were usually obvious and readily fixed without violating the integrity of the design.

Much more impressive are the mistakes Babbage didn’t make. For example, one of Swade’s engineers looked at the design and said it would be impossible to run from a hand crank—the combined resistance from 4,000 gears meshing was just too great. The team went ahead anyway, and of course the engineer was proved right. Then they noticed a mysterious spring mechanism that Babbage had enclosed within the engine frame. Since no one knew its function, it had not yet been installed. And, yes, the purpose of the spring arrangement was to ease the frictional pressures so the hand crank worked as envisaged—an altogether astonishing degree of foresight for a paper design.

A modern realization of Charles Babbage’s Difference Engine No. 2, a distant prototype for the modern computer. It was constructed at the London Science Museum over a six-year period, and completed in time for the Babbage centennial in 1991. The vertical columns mostly contain brass wheels—some 4,000 in total—each of which represents a digit or part of an action. The construction proved that Babbage’s paper designs worked the way he said they would. The modern reconstruction used current machine-tool and dimensioning technology. Whether the machine could have been built with 1830s technology is still an open question.

Some other difficulties, especially in the assembly of the machine, are instructive. Swade’s words:

When parts were first offered up to the machine they were rarely in the correct orientation, and had to be adjusted by trial and error so that their motions harmonised with those of the rest of the mechanism. This is a tentative and exploratory process, and Babbage gives no clues to how the parts are to be oriented correctly. He blithely shows gears and levers fitted in their correct positions and fixed permanently on their shafts by pins driven through both parts locking them to each other immovably. There is no indication of how the correct rotational position of the gear is to be found before it is finally fixed. So the timing of hundreds of parts had to be determined by meticulous trial and error.

35The team did not quite make their schedule. They had preannounced a test case, computing a table of the digits 1 through 80 raised to the seventh power. The machine readily made the calculations but repeatedly failed to get through the entire list before something jammed. Since the test case had been preannounced, they feared that their miss would make the whole project look like a failure. After shamefacedly explaining their shortfall at a crowded press conference, they started the engine and discovered, happily, that no one cared about their test. Swade writes that the crank handle was turned, and “the rhythmic clanking and the shifting array of bronze wheels begins. The helical carry mechanisms perform their rippling dance. There are murmurs as the motions enthral and seduce. The visual spectacle of the engine works its magic. As a static exhibit, the engine is a superb piece of engineering sculpture. As a working machine, even partially working, it is arresting.... The Engine has cast its spell, and later that day the coverage is ungrudgingly triumphalist.”

36 Within some weeks, the DE2 was flawlessly executing the test exercise over and over again. All in all, the exercise was a stupendous success and a classic example of the contributions to history and science of the best science museums.

The experience may also suggest that the various authorities who declined to provide Babbage the open-ended support he had demanded made the right decision. In ten years of off-and-on work on the DE1, Clement completed some 12,000 gears, about half the required total. Swade and his subcontractors produced 4,000 such parts in just six months using a large number of subcontractors in pattern making, gear cutting, case hardening, and many other subtrades. Gears were cut and parts were shaped with CNC (computerized numerical control) machines that can machine hundreds or thousands of parts to precise specifications with great consistency. At the level of precision that Clement was working to—2/1,000 of an inch, according to Swade’s sample—it would have been very difficult for him to replicate the museum team’s accomplishment. In 1830s the technology of precise working drawings and reliable dimensioning tools was still in its infancy. Identical parts were made so by laboriously fitting them to other parts. Drift away from uniformity would have been hard to avoid. And recall the problems Swade’s team had in placing and orienting all the different parts, despite the high precision of CNC machining. It would have been much harder in Babbage’s day. Even with the best of will and resources, it is easy to imagine the project collapsing in ignominious failure with finger-pointing and rancor on all sides.

qAn intellectual achievement as monumental as the Analytical Engine is its own justification, and Babbage deserves a high place in history for it. But like Whitworth’s millionth-of-an-inch measuring machine, it was another beautiful British dead end. Swade notes that Babbage never considered the cost-benefit aspect of his great projects, assuming that government officials would be as drawn as he was to “ingenuity, intricacy, mastery of mechanism, and the seductive appeal of control over number.”

37Babbage was undoubtedly at the extreme end of other-worldliness, but he had a large and responsive audience. A book he published in 1833,

On the Economy of Machinery and Manufacturing,

38 has an arid, academic tone; the first third is an exhaustive classification of machines as those for “Accumulating Power,” “Regulating Power,” “Extending the Time of Action of Forces,” and much else in that vein. Yet the first printing of 3,000 copies was sold out within a few weeks, and there were two more editions the next year. (The first printing of Charles Dickens’s

A Christmas Carol, deemed “an immediate success with the public,” sold 6,000 copies.)

Babbage opens his book with a paean that played directly into the growing British self-satisfaction with their industrial triumphs:

There exists, perhaps, no single circumstance that distinguishes our country more remarkably from all others, than the vast extent and perfection to which we have carried the contrivance of tools and machines for forming those conveniences of which so large a quantity is consumed by almost every class of the community. . . . If we look around at the rooms we inhabit, or through those storehouses of every convenience, of every luxury that man can desire, which deck the crowded streets of our larger cities, we shall find . . . in the art of making even the most insignificant of them, processes calculated to excite our imagination by their simplicity, or to rivet our attention by their unlooked-for results.

The book positioned him as a thought leader in achieving a new synthesis of traditional culture and manufacturing. Instead of merely lamenting Blake’s “dark Satanic mills,” thinkers like Carlyle extolled the coming of an “organic society” that integrated the “Dynamical” and “Mechanical” aspects of human nature.

39 Babbage plays directly to that sentiment, emphasizing the utilitarian beauty of machines and the elegant objects of art—the machined rosettes, lithographs, and engravings—that they can produce, or reproduce, for the masses.

Great Britain’s mid-century Crystal Palace Exhibition (see Chapter 7) was organized on much the same principle: it celebrated not only the nation’s technical preeminence but also the new intellectual order it signified. The exhibition’s royal patron, Prince Albert, organized a yearlong lecture series to explore precisely that theme: that industrial capitalism was allowing “man to approach a more complete fulfillment of that great and sacred mission which he has to perform in this world.” (There can be no doubt that by “man” he meant Anglo-Saxons.) The inaugural lecture was delivered by the master of Trinity College, William Whewell, who eulogized “the Machinery mighty as the thunderbolt to rend the oak, or light as the breath of air that carries the flower-dust to its appointed place.”

40Self-satisfaction is a dangerous sentiment for any competitor but may be understandable in the British case, since with Napoleon vanquished, there were no obvious threats on the horizon. Yet the country’s industrial revolution was advanced enough that both proprietors and workers were deeply invested in established methods. Scar tissue still remained from the fierce Luddite attacks against textile mills in the first years of the century, and the severely repressive response of the government. With the production machinery seemingly working well enough, it was seductively easy to ignore British industrial rigidities and concentrate instead on attractive challenges, like pushing out the boundaries of precision or defining a new aesthetic for an industrial age.

The Americans had no such inclinations, and since they were starting over, they faced almost no entrenched interests. Ironically, what became an American specialty, the extension of the textile-mill model of mechanized mass production to almost every major industry, was also pioneered in Great Britain, but the innovation was stillborn. The story requires winding the camera back to a critical juncture in the Napoleonic wars.

The Portsmouth Block-Making Factory

The prototype for all plants engaged in mass production of heavy industrial goods by self-acting machinery is the famous British ship-block factory at Portsmouth. It was the creation of the young Henry Maudslay and two other extraordinary men, Samuel Bentham and Marc Isambard Brunel, and was in full operation the first years of the century.

41Bentham, the younger brother of the utilitarian philosopher Jeremy, was a naval architect, an inventor, and something of an adventurer. He traveled to Russia as a young man to examine mining and engineering works, was a social hit at the Russian court, fell in love with a young noblewoman, and became the close friend of the Most Serene Prince Grigory Alexandrovich Potemkin, himself a special favorite of Catherine the Great. Bentham created Western-style factories on Potemkin’s estate, built a fleet of warships, distinguished himself in Russia’s sea battles against the Turks, and may have been the first to use shells in naval artillery. On his return to England, his top-drawer connections helped secure him an appointment as inspector general of the navy. Among his many talents, he was an inventor with strong ideas about mechanizing the shipyards.

Brunel, a native of France, was a royalist naval officer forced to flee the avenging angels of the French Revolution. Landing in America, he worked for a half-dozen years designing canals and harbor fortifications, building a cannon foundry, and serving as chief engineer of New York City. Brunel was also a machinery inventor who filed many patents over his lifetime. At dinner at Alexander Hamilton’s home, a guest held forth on Great Britain’s struggle to produce ship blocks—a problem that Brunel was convinced he knew how to solve. Not yet thirty, he embarked for London, the home of his fiancée, a well-connected young Englishwoman, whom he had courted during his flight from France. He duly married on his return and became one of London’s leading engineers, most famous for his pedestrian tunnel under the Thames at Rotherhite. (It took more than twenty years to complete and nearly brought him to ruin.)

Ship blocks—the enclosed pulleys that managed the miles of rope on a warship—were made of solid blocks of wood, with slots, or mortises, for one to four sheaves, or rotating pulleys. The shells were cut from logs of elm, while the sheaves were made of imported lignum vitae, a very hard and durable wood. The sheaves turned on pins made of either lignum vitae or iron, encased in friction-reducing brass bushings, or coaks. Major warships needed somewhere between 1,000 and 1,400 ship blocks, ranging in size from single-sheaved blocks a few inches long to four-sheaved blocks standing nearly four feet high. Badly made blocks could snag rigging, slow maneuvers, and endanger a ship. A single family had enjoyed an effective monopoly over naval ship-block making for nearly fifty years. Their factories were partially mechanized, but Bentham thought them excessively expensive; he had himself developed designs for more efficient machine production.

Brunel arrived in England with fairly complete drawings for four block-making machines and with a working model of at least one of them. He first met with the contractors, who had little interest in his plans, and then secured an appointment with Bentham. Before the meeting, he contracted for two more working models, fortuitously with Maudslay, who was only recently set up in his own shop. (A French acquaintance in London regularly strolled by Maudslay’s shop and told Brunel of the beauty of the display pieces in the window.) Brunel was worried about premature disclosure and at their first meeting refused to tell Maudslay the purpose of his designs. But at the second meeting, Maudslay said, “Ah! Now I see what you are thinking of; you want machinery for making blocks!”

42The Bentham-Brunel meeting, when it took place sometime in mid-1801, was a vendor’s dream. Bentham examined the drawings and the models, generously pronounced them superior to his own, and arranged an early demonstration before the naval board. A contract was awarded in 1802, and Brunel was appointed manager of a new works to be erected at Portsmouth. Maudslay began delivering machines before the end of the year. The new plant was in full production and the old contractors were out of business before the end of 1805. There were two production streams, one for the blocks and one for the sheaves. The metal pins and coaks continued to be produced by traditional methods.

The block production line started with a phalanx of saws of different sizes to cut elm logs into square blocks, followed by a succession of boring, chiseling, sawing, and shaping machines to place and cut the mortises and pin channels, trim and shape the blocks, and cut the channels for the straps that secured them in the rigging.

The sheave line began with specialty crown saws, which looked like a king’s crown lying on its side, with a saw size for each type of sheave. A succession of three machines centered and cut the coak holes in the rough-sawn sheaves, placed and riveted the coaks, and reamed the coak holes into true cylinders. Finally, the sheaves were turned in a lathe that trimmed the face and edges to flat surfaces, and cut the pulley grooves for ropes.

There were just two manual processes in the woodworking: sand-finishing the blocks and the final assembly of the shells and sheavings. The total of all machines, including the saws, was about forty-five.

The machines themselves were classic Maudslay: precision slide rests, screw drives, and gear changers resting in a heavy cast-iron base. Cutting tools were of the best tool steel, and almost all of the machines were self-acting. When a mortise was cut through, for instance, an automatic stop triggered a new sequence to reposition the tool and move the block to the next cut. Only the facing machine required the presence of a skilled turner.

The factory was in full operation for more than fifty years, and no machine was ever replaced. A brochure from 1854 reports that “the only noise arises from the instruments actually in contact with work under execution, and none from the working of the machinery,” but that’s the way all Maudslay machines worked.

43 The plant phased down as the age of iron and steel warships dawned, and the machines were gradually moved to museums, although some of the original machines ran for up to 145 years.

The industrial historian Carolyn Cooper has matched machine descriptions to the still-extant belting shafts and pulleys and still-visible floor markings in the factory, and mined old documents and Brunel’s notes and records to reconstruct the factory’s output, layout, and processing flows.

The flow process was clearly thought through with care—which was unusual in that period, even in the much-touted American armories. Work in process was moved from station to station in wheeled bins. Output was high: the large mortise chisels ran at a hundred strokes per minute, and the blocks were advanced

of an inch at each stroke. One man could bore and mortise 500 6-inch or 120 16-inch single-sheaved blocks in eleven and a half hours—that’s two operations in about a minute and a half for the smaller blocks, and in less than six minutes for the larger ones. A figure widely quoted from Brunel’s biographer, however, that 110 men had been replaced with only 10, should probably be taken with a grain of salt.

rThe best estimate for the cost savings comes from the payment to Brunel, which by contract was to be equal to the savings realized in the first year after the plant achieved full operations—a very Benthamite arrangement, for brother Jeremy had long advocated for government performance contracting. The actual payment award was £17,000, based on 1808 production of 130,000 blocks at a cost of £50,000, which suggests a 25 percent savings (17,000/[17,000 + 50,000]). That tracks well with a “generally accepted,” mid-nineteenth-century estimate reported by Cooper that the plant paid for itself within four years.

44 All in all, the venture must be considered a superb success, especially since the savings kept rolling in for many years after the investment was fully recovered.

Bentham and Brunel, of course, were extremely proud of their plant, and the government was delighted for once to crow about its rigorous cost management. But as a torchlight pointing toward new directions in manufacturing, the Portsmouth plant utterly fizzled. The British trumpeted its virtues, tourists oohed and aahed their way through, but it made no impact on the style and methods of British industry. Cooper has unearthed possible half-hearted imitations here and there, but nothing important or lasting.

So we see the British intellectualizing their industrial accomplishments, complacent with their methods and processes, and through most of the nineteenth century oblivious to the empirical and often original approaches of the Americans.

That may be the fate of winners, for Americans made the same mistakes a century later. In the 1950s and 1960s, executive self-celebration was assiduously watered by business school professors, who had begun churning out students with master’s degrees in business administration, trained mostly in blackboard-compatible topics like finance and organization. A complacent American corporate elite, ignorant of the shop floors in their own plants, were utterly oblivious to the storm that was about to be unleashed by the new plants, the new tools, and striking new approaches taken by waves of hungry new competitors, first from Germany and Japan, and then from nearly the whole of east and south Asia.

45

of an inch at each stroke. One man could bore and mortise 500 6-inch or 120 16-inch single-sheaved blocks in eleven and a half hours—that’s two operations in about a minute and a half for the smaller blocks, and in less than six minutes for the larger ones. A figure widely quoted from Brunel’s biographer, however, that 110 men had been replaced with only 10, should probably be taken with a grain of salt.r

of an inch at each stroke. One man could bore and mortise 500 6-inch or 120 16-inch single-sheaved blocks in eleven and a half hours—that’s two operations in about a minute and a half for the smaller blocks, and in less than six minutes for the larger ones. A figure widely quoted from Brunel’s biographer, however, that 110 men had been replaced with only 10, should probably be taken with a grain of salt.r