CHAPTER FIVE

The Rise of the West

FRANCES TROLLOPE WAS FORTY-SEVEN IN FEBRUARY 1828, WHEN SHE disembarked at Cincinnati with three of her five children in tow. She knew no one in the city and had made the last leg of her trip on borrowed money. Two sons, Tom, the oldest, and Anthony, the future novelist, were both in school in England, while her contentious and ineffective husband, a failed lawyer and a failed farmer, remained on their estate near Harrow to stave off creditors.

1

The notion of publishing what was to be the wittiest, sharpest, and most caustic traveler’s account of Jacksonian America was furthest from Trollope’s mind. She had come to Cincinnati to repair the family finances by opening a proto-department store offering fine European goods to the grandees of Cincinnati—assuming there were such persons, for her research had consisted only of some pamphlets and conversations with a friend who had once passed through the city.

Despite her dubious judgment in practicalities, Trollope’s adventure revealed a woman of rare intelligence, energy, and resilience. Her first year in Cincinnati she made money as the impresario of an elaborate, quasi-mechanical staging of Dante’s

Inferno at the Cincinnati museum. (Her son Henry did the voice of an invisible Oracle in Latin and Greek.) The production was reported as far away as Boston and ran for years. Samuel Colt, nineteen years old and touring the West as “Dr. Coult” delivering laughing-gas exhibitions and science lectures to raise money for his pistols, did a stint with the show in 1833.

2 The humorist Artemus Ward commented on it in 1861.

But Trollope had come to open a store and spent huge amounts of other people’s money constructing it. Her “Bazaar” was a pastiche of Gothic and Byzantine architecture, eighty-five feet high. The shipments of expensive French fabrics her husband sent drew no customers, however, so the project was quickly underwater. The day after the sheriff distrained her household goods, Trollope gathered her children and absconded on a steamboat. She had spent twenty-five months in Cincinnati, leaving the Bazaar as her monument or, depending on her mood, her revenge.

With her family in desperate financial straits and her husband of no use, Trollope decided to extend her trip and recoup their fortunes by writing a book. She had never published anything and needed to scrape and scrounge to finance too-short visits to the South and New England. But she wrote beautifully. The book opens with her arrival from England at the mouth of the Mississippi, and she meditates briefly on the difficulty of recording scenery: “The Ohio and the Potomac may mingle and be confounded with other streams in my memory, I may even recall with difficulty the blue outline of the Alleghany mountains, but never, while I can remember any thing, shall I forget the first and last hour of light upon the Atlantic.”

3Trollope finished her book after she returned to England, working in the mean little farmhouse where her husband, having lost his estate, was sunk in invalidism. The first publisher she favored with the manuscript loved it, and The Domestic Manners of the Americans was a best seller on both sides of the Atlantic.

The new fortune was quickly squandered, but she kept writing, turning out 113 volumes of novels and travel books. Because of the Trollopes’ financial heedlessness, her first books after Domestic Manners were again written under great financial pressure, made the worse by the successive deaths of her husband and two of her children. But she emerged from her crises in full blossom and lived to be eighty-three, hale and active to the very end, finally wealthy, a success throughout Europe, an invitee at royal courts. When she was not traveling, she made her home in Florence, at Villino Trollope, where she was surrounded by her family, artistic friends, and a constant stream of visitors.

Posterity is fortunate in the foreign literary travelers who graced the United States in the crucial decades from the 1820s through the 1840s. Besides Trollope, there were Alexis de Tocqueville and his partner, Gustav de Beaumont, the most famous European rapporteurs on things American. They arrived in 1831 and covered some 3,000 miles in just ten months. Harriet Martineau, one of the world’s first female political economists/sociologists, traveled for two years in 1835–1836, living almost everywhere, in both mansions and log cabins, and meeting almost everybody, including Jackson and Madison. Her

Society in America (1837) is remarkable for both the lucidity of her mind and prose and her de haut en bas lectures on the solutions to America’s problems. Charles Dickens compiled his

American Notes during a four-month tour in 1842. He came to deliver a series of paid lectures and readings in the major eastern cities, but rounded out his trip with flying visits to Washington and Virginia, and to the “West,” the rich but thinly populated expanse between the inland slopes of the Appalachians and the Mississippi River.

ar Trollope was in the United States longer than any of these, but more than half of her stay was confined to Cincinnati.

Each of their accounts is quite different, but there are some common threads. They had all arrived as opponents of slavery but were shocked and horrified when they confronted its reality, and felt the American prating of “liberty and equality” as the deepest hypocrisy. All were variously appalled at the strict separation of men and women in inns and public conveyances; the huge quantities of food consumed by Americans, how fast they ate, and the lack of conversation at meals; and, worst of all, the constant chawing and spitting by American men—spitting indoors and outdoors, on good carpets and bare floors. It does sound awful; Dickens had the misfortune to take the lowest of a stack of bunks on a canal boat and awoke to find his coat drenched with spit from the upper bunks.

At a broader level, all of them understood that they were observing a vast interlacing of the country, as the northeastern and Middle Atlantic states were being drawn into tight commercial relations with the West. They were all stunned at the commercialism and struggled to understand the mechanics of a society without official classes. And, as with many of their impressions of American innovations, they were as dazzled by the beauty and adaptability of the western steamboat as they were appalled by its evident dangers.

Nascent Colossus

In the modern era, an emerging-market country typically industrializes by exploiting cheap labor to become a low-cost manufacturing site for developed country markets, and then moves rapidly up the technology curve to higher-margin output. It was the model followed with great success by Japan in the early twentieth century and has been successfully adapted by most of the Asian Pacific Rim countries over the last thirty years or so.

At first glance, the nineteenth-century American pattern appears to be quite different, because labor was generally more expensive in the United States than in Europe. But only free labor was expensive. The United States had a huge reservoir of cheap labor—slaves—who produced the cotton that accounted for about half the value of American exports from 1820 through 1860. Over the same period, only about 15 percent of American exports were manufactured or semimanufactured goods. Everything else was extractive or farm-related—wheat and tobacco (which taken together were dwarfed by cotton), lumber, ores and metals, and processed foods.

4America’s primary imports, on the other hand, were heavily tilted to manufactures, altogether about 63 percent of all imports during the period. Some of those comprised luxury goods, like gowns, mirrors, fine china, and the like, but a very large share was the high quality steel, engines, rails, tools, and other capital goods needed to power America’s leap into the industrial age. America had chronic trade deficits, but except during financial disruptions, they were typically small. The accumulated deficit during the whole 1820–1860 period was about $175 million, or a little over $4 million a year, but it still had to be financed.

5

PREBELLUM FINANCE

The United States was not a capital-rich country, and its annual trade deficits had to be covered by shipping gold, by increasing exports, or from inflows of foreign investment. Mega-projects, like canals or railroads, were normally financed by state bond issues, which were sold through American and English banking houses. (The last of the federal debt was discharged in 1835, so there was no Treasury bond market.) A sample of American state bond yields in London and New York from the first half of the 1830s shows spread differentials only in the few hundredths of a percent, suggesting tight integration of the two countries’ capital markets.

The splendid success of the Erie Canal, which had been financed with New York bonds, created an eager British market for American canal and railroad bonds. To the British upper classes sitting on inherited low-yielding British consols, American bonds were attractive investment-grade, high-yield paper, so about half of all American canal and railroad-related bonds were held in Great Britain. A spate of canal and railroad building from 1836 to 1842 drew at least $60 million from abroad and was a substantial factor in the American recovery from the 1837 recession.

The ease of bond sales created something of a canal and railroad bubble. A substantial number of newer state bonds, from Indiana, Michigan, Illinois, Arkansas, and Florida, defaulted. They had been mostly issued in the later stages of the market cycle, and most were eventually repudiated. Eastern state bonds continued to perform well, with the exception of Pennsylvania’s. That state’s businessmen, alarmed by the withering competition from the Erie Canal, had pressured the government to finance hundreds of miles of canals just on the eve of the railroad age. While almost all American bonds took a reputational hit, differential spreads in London suggest that foreign investors were well able to discriminate between sound offerings and junk.

6Entrepreneurial capital mostly came from personal or family savings, as it still does today. Business startup costs were certainly lower than today, and a skilled craftsman could often make most of his tools and equipment himself. Local merchants also provided capital for likely entrepreneurs, while more expensive startups, like a substantial forge, might get the support of an informal consortium of leading men of an area. The Holley family and their partners financed most of their businesses from their own resources but joined with other leading merchants and business men to found a local bank.

The commercial banking industry of the day was mostly about trade, in accord with the prevailing “real bills” doctrine, which held that bankers should lend only against goods moving in trade to bridge the cash-flow gap between a sale and the receipt of payment. As raw materials production shifted to the West, trade finance was a major development bottleneck. Local banks naturally sprang up to meet the challenge, but often with indifferent results. In theory, farmers could contract with coastal merchants’ agents for the sale of their crop at a future date and receive a “bill of exchange,” equivalent to a check, payable in the future when the crops were delivered. A local bank would discount the bill—that is, buy it from the farmer for cash at a discount from face value to cover collection costs—and collect on the bill from the merchant house when the crops were shipped.

In reality, the combination of the distances, the extended performance periods, and the limited liquidity of local banks made the process highly prone to breakdown. Since illiquid local banks would of necessity quickly rediscount their bills, and often pay penalty discounts themselves, all of those costs were deducted from the initial payment to the farmer. Much of the time, the farmer’s discounted proceeds did not cover his real costs, trapping him in a continuing debt spiral. The system’s instability was greatly aggravated by the refusal of foreign traders to accept American bills, so import payments had to be made in scarce coin. Hard-money Republicans increased the funding pressure by insisting on accelerating the payment of the public debt. The debt was payable in specie, and much of it was held abroad, so debt retirement drained away gold reserves.

For a relatively brief period, however, through much of the 1820s, when Nicholas Biddle was at the helm of the Second Bank of the United States,

as the country’s internal monetary system functioned as well as any in the world. Biddle was a dilettante, a Philadelphia nouveau-aristocrat, a dabbler in painting and poetry, and the compiler of the popular edition of the Lewis and Clark journals. He was also very intelligent and arguably the first to understand both the regulatory and the monetary roles of a central banker.

7First and foremost, Biddle was a careful manager of his own bank’s positions, and he maintained a strong relation with Barings, so within a year or so after his ascendance, the notes of the Bank of the United States (BUS) were accepted almost everywhere near par. More important, the high reputation of the Bank’s notes gave Biddle de facto regulatory leverage over local banks. Since the BUS applied strict and consistent standards before accepting local bank note issuances, the merchant community quickly learned to accept only notes approved by the BUS. At a stroke, BUS notes and approved local notes became a national mercantile currency. And since Biddle was willing to provide BUS notes to well-managed local banks, interior liquidity was greatly increased, the steep interior discounting rates shrank dramatically, the pace of commerce quickened, and interior incomes rose. A related benefit was an easing of the specie shortage. Once the discount demanded by foreign acceptors of BUS notes fell below the cost of shipping specie, they stopped demanding payment in coin.

Biddle also understood a central bank’s role of easing credit at times of temporary market stress. (During this period, the Bank of England reflexively pulled back credit to protect its own specie at the barest hint of problems, displaying in the words of one authority, “an inexcusable degree of incompetence.”

8) Biddle, by contrast, tuned his collection procedures to the state of the economy. Rather than increase pressure on merchant houses when credit was tight, he would let his notes remain uncollected until conditions eased—effectively expanding the money supply. Similarly, when animal spirits were on the boil, he would reduce his discounting activity and speed up on collections. In 1825, 1827–1828, and 1830–1831, he steered the United States through major credit contractions caused by typically benighted specie-hoarding policies at the Bank of England.

9That happy state of affairs existed for most of the 1820s, a period labeled in elementary history texts as the Era of Good Feelings. It ended when Andrew Jackson, in a triumph of prejudice and ignorance, vetoed a bill reauthorizing the BUS. (It had passed both the House and the Senate by good margins but was two short of the votes required to override a veto.) Jackson was heavily influenced by people like Amos Kendall, his postmaster general, an early telegraph entrepreneur, and a radical advocate of laissez-faire, who believed the BUS to be a near-biblical scourge. Another close banking adviser, William Gouge, a former newspaperman who was knowledgeable in finance, insisted that banking “was the principal cause of social evil in the United States.”

at Gouge and Kendall held their views sincerely, but many of the businessmen in the Jacksonian Kitchen Cabinet were tied to bankers who greatly resented the BUS’s restraining hand.

10Biddle didn’t help his case by his aristocratic style or his dismissiveness of people less intelligent than he. His reputation was finally destroyed by his hopeless and ultimately vindictive rearguard action against Jackson’s veto, which succeeded only in creating a political firestorm and rattling the entire economy. Once the BUS’s charter expired in 1836, he rechar-tered it in Pennsylvania and seems to have deluded himself that he could replicate the position of the old BUS from a state platform. He was quickly overextended and not only destroyed the Bank but hastened the collapse of the state’s canal-stretched finances. It was a time when the transatlantic financial system was badly strained by excesses in western land, in canals, in cotton, and much else. If the BUS had survived with Biddle as president, he might have considerably ameliorated the American crisis, but in his new incarnation as an overreaching head of a state bank, he materially contributed to the excesses. It took more than a century before historians discovered his earlier accomplishments.

With the demise of the BUS, state banks once again came into their own. “Free banking” legislation spread, especially in the West. Some, indeed, were sober and well-run institutions, but in many states they were mere engines of chicanery, shipping the same small trove of gold coin from one bank to the next to stay ahead of auditors, and pumping out notes beyond reason. “Wild cat” banking referred to some bankers’ hiding “in the woods where the wild cats are” to avoid having to redeem their notes. The key to success, counseled one banker, was to create such gorgeous notes that the rubes would never redeem them: “a real furioso plate, one that will take with all creation—flaming with cupids, locomotives, rural scenery, and Hercules kicking the world over.” While there appears to be no truth in the tales of western farmers hauling wagons full of bank notes on provisioning trips, the shutdown of the BUS ushered in a long period of financial instability. Remarkably, it does not appear to have interfered much with the average rate of growth, although the stomach-churning year-to-year ups and downs must have inflicted great hardship.

11

THE SOUTH AND THE REST

As an industrial boom took hold in the rest of the country, the South slipped into the position of an internal colony. In effect, the South exploited its slaves, while the rest of the country exploited the South. Cotton prices were generally strong from the 1830s until the Civil War, and virtually all the South’s resources were sucked into cotton production. Cotton was very profitable, but the first large slice of cotton profits accrued to Northern finance houses in the form of hefty trading, marketing, shipping, banking, and insurance revenues. The earnings that did flow to the South mostly flowed right back out again, for food from the West and for western and northern manufactures. By the 1840s, the everyday clothes and shoes worn by Southerners were made in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and New York. The steam engines, farm tools, grain, and packed meats they needed came down the Ohio and Mississippi from Cincinnati, Louisville, and Pittsburgh. The schools the planter elite chose for their children were in New Jersey, New York, and New England.

12By 1860, the West, New England, and the Middle Atlantic states were rapidly evolving into an approximation of a unified commercial and industrial economy. Erie Canal traffic is a good proxy for the integration: after it opened, the traffic was primarily between western New York and the coastal cities, but by 1860 the eastward traffic originated primarily in the West.

13Unlike the South, the West invested its agricultural surpluses in businesses and public infrastructure, like railroads. Much as in Massachusetts a few decades before, the intense commercialization of agriculture was creating larger, mechanized farms, and the agricultural workforce was shifting to higher productivity industrial employment. By mid-century, the United States had the second-largest GDP in the world, and the second-largest per capita GDP. Great Britain was still far ahead, with nearly three times the output as America. But the United States had the fastest growth rate in industrial production by far than any other country, on both an overall and per capita basis, and with a rapidly growing adult population besides.

14

Striving

Foreign travelers in America were uniformly stunned by the commercialism. Tocqueville wrote, “I know of no country, indeed, where wealth has taken a stronger hold on the affections of men.”

15 But the full reality didn’t dawn on him until he was in Ohio, when he wrote, “The entire society is a factory!”

16 Harriet Martineau noted that bad roads limited the availability of some goods in the interior, but still, she wrote: “When a few other neighbors besides frogs, gather round the settler, some one opens a grocery store. [On the Niagara peninsula] . . . there is a store on the borders of the forest. I saw there glass and bacon; staylaces, prints, drugs, rugs, and crockery; bombazeens and tin cans; books, boots, and moist sugar, &c. &c.”

17Trollope found the source of American industriousness in “the unceasing goad which necessity applies to industry.” During her stay in Cincinnati, she reported, “I neither saw a beggar, nor a man of sufficient fortune to permit his ceasing his effort to increase it.”

18She was ambivalent, at best, about the constant drive for advancement. A young, energetic, illiterate farmer she knew made a favorable impression. He and his family had “plenty of beef-steaks and onions” three times a day. Besides tending his farm, he cleared forests, split rails and built fences, built a new house, rented half of it, contracted to build a bridge, and opened a store. Trollope had “no doubt that every sun that sets sees him a richer man than when it rose.” The farmer hoped his son would become a lawyer, and she supposed he would, and would “sit in congress” besides, and “the idea that his origin is a disadvantage, will never occur to the imagination of the most exalted of his fellow-citizens.”

19But in her heart of hearts, she thought a society

needed proper class divisions to function, and their absence in America was disorienting: “The greatest difficulty . . . is getting servants, or as it is there called, ‘getting help,’ for it is more than a petty treason to the Republic, to call a free citizen a

servant.... Hundreds of half-naked girls work in the paper-mills, or in any other manufactory, for less than half the wages they would receive in service; but they think their equality is compromised by the latter.” When Trollope finally found “a tall, stately lass” she liked, she asked what “I should give her by the year.” The girl laughed out loud. “You be a downright Englisher, sure enough. I should like to see a young lady engage by the year in America!”—and explained that she might get married or decide to go to school. Her work proved satisfactory enough, but she resigned in a huff when Trollope refused to lend the price of a ball gown—“Then ’tis not worth my while to stay any longer.”

20

Mrs. Trollope. Engraving executed in 1845 after an oil painted around 1832 by a young French artist, Auguste Hervieu. The Trollopes had acted as Hervieu’s patrons in England, and he traveled to America with the family as part of the household.

“All animal wants are supplied profusely at Cincinnati,” Trollope conceded, “and at a very easy rate.” But the leveling tendency left no room for “the little elegancies and refinements enjoyed by the middle classes in Europe,” and she missed them. “Were I an English legislator,” Trollope wrote, “instead of sending sedition to the Tower, I would send her to make a tour of the United States. I had a little leaning towards sedition myself when I set out, but before I had half completed my tour I was quite cured.”

21Dickens rather enjoyed the leveling, because it made good copy. But it was behavior he would have regarded as “impertinencies” in England—like the inn proprietor walking in and out of his rooms with his hat on, or that worthy’s practice of starting conversations “in a free-and-easy manner,” or lying down on Dickens’s sofa to read his paper. In America, it was all just part of being a “good-natured fellow,” he wrote, with more than a tad of sarcasm.

au But he clearly liked “the funny old lady,” who, “when she came to wait upon us at any meal, sat herself down comfortably in the most convenient chair, and, producing a large pin to pick her teeth with, remained performing that ceremony, and steadfastly regarding us meanwhile with much gravity and composure (now and then pressing us to eat a little more), until it was time to clear away. It was enough for us that [the service] . . . was performed with great civility and readiness, and a desire to oblige.”

22Martineau, who was of Radical politics in England, urged Europeans to adjust their manners to the Americans’:

It should never be forgotten that it is usually a matter of necessity, or of favour, seldom of choice (except in the towns,) that the wife and daughters of American citizens render service to travellers. Such a breaking in upon their domestic quiet, such an exposure to the society of casual travellers, must be so distasteful to them generally as to excuse any apparent want of cordiality.... [Look instead for] the cordiality which brightens up at your offer to make your own bed, mend your own fire, &c.—the cordiality which brings your hostess into your parlor, to draw her chair and be sociable, not only by asking where you are going, but by telling you all that interests her in her neighborhood.

23It was Tocqueville, the royalist, a child of the ancien régime whose family had been decimated by the guillotine, who thought most intensely about the leveling impulse and penetrated the deepest. He and Beaumont took the steamboat to Albany and attended a Fourth of July ceremony, where they were moved by the solemn reading of the Declaration of Independence. They had planned to spend time there investigating the workings of state government. But as Tocqueville wrote to a friend, “The offices and registers were all open to us, but as far as government goes, we’re still looking for it. Really it doesn’t exist at all.” There had been no police attending the ceremony they had witnessed; but while it was humble by European standards, it was still perfectly orderly. The parade marshal was a volunteer with no official status, yet everyone obeyed him.

Comprehension dawned in Ohio. This, Tocqueville understood, was democracy without limit, “absolutely without precedents, without traditions, without customs, without even prevailing ideas.” For his own class in France, “the family represents the land and the land represents the family . . . an imperishable witness to the past and a precious pledge for the future.” But Americans “flee the paternal hearth . . . to chase after fortune—nothing, in their eyes, is more praiseworthy.”

“An American taken at random,” he went on, “will be ardent in his desires, enterprising, adventurous, and above all an innovator.” And when they meet each other, though they may differ greatly in wealth, “they regard each other without pride on the one side and without envy on the other. At bottom they feel themselves equal, and they are.” And he explained why:

Imagine if you can, my friend, a society formed from all the nations of the world—English, French, German.... All of these people have different languages, beliefs, and opinions. In a word, it’s a society without roots, memories, biases, routines, shared ideas, or national character, and yet it’s a hundred times more fortunate than our own. More virtuous? I doubt it. So there’s the point of departure: What serves to bond such diverse elements? What makes a people of all of this? L’intérêt! That’s the secret: the interest of individuals that comes through at every moment, and declares itself openly as a social theory.

For Tocqueville, Ohio demonstrated “one thing I had doubted until now, that the middle classes can govern a state.... They do definitely supply practical intelligence, and that turns out to be enough.” As he put it in Democracy in America: “The doctrine of interest, properly understood does not produce great sacrifices, but day by day it prompts little ones. By itself it cannot make a man virtuous, but it shapes a multitude of citizens who are orderly, temperate, moderate, foresighted, and masters of themselves. And if that doesn’t lead directly to virtue through the will, it advances gradually closer to virtue through the habits.”

So the leveling imperative—the assumption of equality that led to the easy familiarity that bemused Dickens and unsettled Trollope; the casualness toward rank that had a president, to European astonishment, shaking hands with anyone who approached him—was not a social disorder. Rather, it was the clue to the country’s success. Tocqueville admitted that he himself could never be completely comfortable in such a society, but few contemporaries understood it so well.

24

The Western Steamboat

At a much less abstract level, all of our travelers, like most Europeans, were deeply impressed with the western river steamboat, a uniquely American invention that was a critical breakthrough for the region’s development. Martineau wrote:

The ports of the United States are, singularly enough, scattered around the whole of their boundaries. Besides those on the seaboard, there are many in the interior; on the northern lakes, and on thousands of miles of deep rivers. No nook in the country is at a despairing distance from a market; and where the usual incentives to enterprise exist, the means of transportation are sure to be provided....

The steam-boats of the United States are renowned as they deserve to be. There is no occasion to describe their size and beauty here; but their number is astonishing. I understand that three hundred were navigating the great western rivers some time ago: and the number is probably much increased.

25The eastern seaboard was blessed with a more or less continuous system of tidal waterways linking almost all the major cities. Rivers like the Hudson and the Connecticut were broad, deep, and relatively straight. For a skilled captain with a good boat, sailing upstream was almost as easy as sailing down. As a teenager, Cornelius Vanderbilt ran a Staten Island–to-Manhattan ferry service with a small sailing sloop. By his early twenties he owned a string of twenty- to thirty-ton fast sailing vessels running freight traffic up and down the East Coast. He could sail up the Delaware during shad season, picking up fishermen’s catches to sell in New York City. Fast, easy, waterborne freight transport facilitated commerce on the eastern seaboard from the earliest days.

26The new steamboats developed on the East Coast early in the century were therefore targeted at passengers rather than freight. The standard boats were large, usually well built, and commodious to the point of grandiosity. Fulton used imported Boulton & Watt–style low-pressure engines from the start (they were long since off patent). Some operators experimented with high-pressure designs, until a rash of boiler explosions pushed the bigger operators into the Boulton & Watt camp until much later in the century. (When a low-pressure boiler failed, it might inundate the deck, but no one got hurt.)

The waterways that so densely veined the interior of the West, by contrast, were shallow, narrow, and winding, often with swift currents. Sailing vessels were close to useless, so downstream shipping was commonly by flat boat, with the craft broken up and sold for lumber at its destination. There were also keel boats that made round trips, but the week or two trip downstream from Louisville to New Orleans was a brutal three- to four-month slog of poling and shoreline towing to get back. Western exports therefore mostly went downriver to New Orleans, while the region imported little back, relying on wagon trekkers crossing the mountains with essential eastern or English manufactures.

The practical effect was that westerners were consigned to a kind of preindustrial self-sufficiency. In 1815, Mt. Pleasant in Jefferson County, Ohio, about ten miles from the Ohio River, was home to “between 80 and 90 families and about 500 souls.” There were some forty different craft establishments—saddlers, hatters, blacksmiths, weavers, bootmakers, carpenters, tailors, cabinetmakers, wagon makers, a baker, and an apothecary. Within a radius of six miles, there were at least two dozen mills of various kinds.

27 These were not isolated settlers, and the town must have been a hive of activity, with almost everything it needed within a convenient wagon ride. Measured by the basics of nutrition and shelter, the standard of living was good, but in such a small-pellet economy, technology was stuck at a handicraft level. The river network could support some regional production, but to exploit it required steam.

28Building a western steamboat network took about twenty years, and involved two East-West face-offs: one between rival entrepreneurs and another between rival designs. Both were won by the West.

Eastern interests made the first move in 1811, when the Livingston-Fulton combine, which owned the profitable Hudson River franchise, acquired an exclusive steamboat franchise from Louisiana. Robert Livingston was one of New York’s richest men. He had been a member of the Committee to Draft the Declaration of Independence, a minister to France, and a key negotiator of the Louisiana Purchase. He had met Robert Fulton in France, where the younger man was experimenting with a military submarine. The two agreed to cooperate on a steamboat venture in New York, and Fulton eventually married Livingston’s niece. Their first successful run, from New York City to Livingston’s Clermont Manor estate on the Hudson took place in 1807. (The boat was officially named Steam Boat but became known to popular history as the Clermont.)

Fulton’s first western boat, the New Orleans (371 tons), left Pittsburgh in October 1811 for the 2,000-mile trip to the Gulf down the Ohio and Mississippi, arriving in New Orleans the following January. The group put three more boats into operation in 1814 and 1815. They were all roughly the size of the New Orleans and mostly concentrated on the much shorter (300 miles) but very lucrative Natchez–New Orleans trade. (Livingston and Fulton died in 1813 and 1815 respectively, which likely slowed the combine’s move into the West.)

Monopoly franchises were pervasive in Great Britain and fairly common in the East, but westerners were outraged at the Louisiana grant. New Orleans was the gateway to the entire West, so a Louisiana monopoly imposed tribute on steamboats from any other riparian territory. The fact that the franchise had gone to easterners only added to the anger. A Pennsylvania group operating out of works in Brownsville on the Monongahela River, some fifty miles south of Pittsburgh, decided to ignore it. The group was headed by two excellent mechanics and engineers, Daniel French and Henry M. Shreve.

av Their boat, the

Enterprise (75 tons), with Shreve at the wheel, made it to New Orleans in 1815. Over the next couple of years, Shreve became locally famous for his clever cat-and-mouse games with New Orleans authorities both on the

Enterprise and on the much bigger

Washington (403 tons).

Everyone sued, and an 1816 federal court decision held that territories could not grant monopolies. By 1818, with all appeals exhausted, the western rivers became open to all comers. By 1819 there were a reported thirty-one steamboats operating in the West, mostly on the 1,350-mile stretch between New Orleans and Louisville, just above the Mississippi–Ohio River junction.

Having banished the monopolists’ business methods, westerners now had to rethink their equipment. The boats launched by the Livingston-Fulton group all followed their Hudson patterns. They were strongly constructed with relatively deep, rounded hulls and were powered by low-pressure engines.

aw It was possible for them to navigate western rivers, as the

New Orleans had proven. But achieving reliable, economic transportation over the vicissitudes of river high and low points required reconciling a number of conflicting demands: the ideal steamboat would be a very light, shallow-draft vessel but one able to carry very heavy loads. It also had to be nimble, with a high power-to-weight ratio for quick response to rapids and other river hazards.

Power-to-weight requirements ruled out the Boulton & Watt–style engines. The engine on a Fulton boat launched at New Orleans in 1815 weighed one hundred tons and generated 60 horsepower, while the one on an 1816 French-Shreve competitor weighed only five tons yet generated a full 100 horsepower. Captains also preferred the high-pressure engines in difficult water because they could generate sudden thrust—a fast “wad of steam”—by tossing a handful of pitch into the firebox. Power in a Boulton & Watt engine was limited by the size of the condenser, regardless of the steam pressure. It also had almost twice as many moving parts and was harder to repair and maintain. The final bonus, of course, was that especially early in the century, the west didn’t have the technical base to build the outsized Boulton & Watt components. A series of extremely simple and elegant engines from French and Shreve steadily increased efficiencies and gradually became the standard for the whole western industry.

axThe high-pressure engines of the era, as we have seen, were dangerous fuel hogs. But fuel costs in the West were too low to really matter. Trollope described the squalid woodcutters’ cabins lining the river banks and the spavined families carrying wood down to the fueling dock for a few coins. And the advantages of the new steamboats were so overwhelming that Americans, and hordes of foreign travelers, chose to live with the risk. Bad as the safety record was, travelers’ reports often exaggerated it. In an 1831 letter, Tocqueville wrote, “Thirty [steamboats] exploded or sank during the first six weeks we were in the United States”—a rate of attrition that would have wiped out the entire American fleet in hardly more than a year.

29A high-efficiency, lightweight engine was just a first step. To achieve the shallow draft, the shape and structure of the steamboat had to be radically reconfigured to present a broad flat surface to the water. Holds were done away with and cargo storage moved to the deck, with lightweight—critics said “flimsy”—superstructures for passengers and pilot house. Paddle wheels were moved higher to accommodate the reduced draft, and they were made larger for greater circumferential speed. The standard boats on arterial rivers typically achieved three- to four-and-a-half-foot drafts empty and five-and-a-half-foot to eight-foot drafts fully loaded. A special breed of “light” boats, able to carry fifty- to two-hundred-ton freights on two feet of water, were built to service tributary rivers that were often sandbar obstacle courses. A wag wrote that the first mate on a light boat could open a keg of beer in front and sail for four miles on the suds. An 1851 British survey of American steamboats reported: “the steamers built for [western] waters carry a greater amount of freight and accommodate a larger number of passengers upon a given draught of water than those constructed in any other part of the world; at the same time, their

cost of construction and outfit per ton of freight capacity, or for passenger accommodation, is very much less.”

30As boat and engine designs stabilized, shipping times dropped markedly. In the early days, the upstream trip from New Orleans to Louisville took about a month, which was a threefold to fourfold improvement over human- or animal-powered upstream times. By the end of the first decade of western steamboating, that same trip was down to about two and a half weeks, and by mid-century, fully loaded business trips to Louisville with normal stops were routinely accomplished in a week or less. Important marginal gains were squeezed out by river improvements, like clearing snags (submerged tree trunks that could destroy a hull) and building canals around strategic obstacles, like the Ohio Falls at Louisville—really a stretch of rapids with a twenty-six-foot fall over two miles. The falls were readily navigable by shallow-draft boats, but standard boats could make it upriver only at peak water levels.

Comparable improvements were made in travel on the Upper Mississippi, to St. Louis and beyond to St. Paul, and on the Upper Ohio from Cincinnati to Pittsburgh. The major tributary water systems were fully integrated into the network in the 1830s, and by the 1840s almost all significant rivers throughout the West, and many throughout the Southeast and Southwest, had some steamboat service. By the late 1840s, important river cities like Cincinnati, St. Louis, and Pittsburgh all averaged about 3,000 steamboat landings a year.

The jump in trip frequencies and freight capacity released an explosion of goods on the West. Western prices had been dominated by transport costs, including for local products. The West was rich in salt mines, but with steamboats on the rivers, the price of salt dropped from $3 a bushel in 1817 to 75 cents by 1825; sugar went from 24 cents a pound to 9 cents. Country stores in the West suddenly had full shelves of glass, hardware, nails, dry goods, and even luxury items, like Wedgewood’s “queen’s ware.” Westerners could also afford imports because they were exporting so much more, like grains, dried or salted meats, and even some steam engines.

31Improved market access spurred the commercialization of farms and accelerated the use of money. Trollope described a farm family she visited in 1828. It was a well-run farm by all indications, and the family was amply provided for, with chickens and other animals, several acres of corn and other crops, well-constructed housing, beds, chests with drawers. “Robinson Crusoe was hardly more independent,” Trollope reported, for they grew all of their food, spun all of their cloth, and made their own shoes. They had no need for money, the wife told her, except occasionally for coffee, tea, or whiskey, and she could get that by sending a “batch of butter and chicken” to market.

32 But such families were a dwindling minority. Ohio farmers were embarked on the same rapid rural-industrialization path that Winifred Rothenberg’s Massachusetts farmers had traversed earlier in the century, but the transition would be much faster.

Building steamboats became a major industry in its own right. After 1820, western factories built an average of one hundred big steamboats a year for nearly the rest of the century, three-quarters of them at Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, and Louisville. Steamboat building jump-started the Ohio and western Pennsylvania iron and coal industries, and the big river cities were soon dotted with large-scale foundries and forges, rolling mills, and heavy machine shops. Glass, paint, and fine furniture industries developed in their wake. New England peddler networks spread out in almost seamless conjunction with every extension of transportation. The big Connecticut brass founders and clock and tinware makers retained their manufacturing dominance by decentralizing their distribution and sales networks, much as the Boston Associates had done in textiles.

33The western population soared from a mere scattering of adventurers in 1800, to 1.6 million in 1830, and to 9 million in 1860, or about 30 percent of the national population. Cincinnati, the queen of western manufacturing cities before the Civil War, saw its population jump exponentially from 2,500 in 1810, to more than 20,000 when Trollope visited, to 46,000 the next decade when Dickens made his stopover, and 115,000 by 1850.

34 While Trollope thought the city rather disorganized and dirty, Dickens implicitly gave it high marks for managing its growth: “Cincinnati is a beautiful city; cheerful, thriving, and animated. I have not often seen a place that commends itself so favourably and pleasantly to a stranger at the first glance as this does: with its clean houses of red and white, its well-paved roads, and footways of bright tile. Nor does it become less prepossessing on a closer acquaintance. The streets are broad and airy, the shops extremely good, the private residences remarkable for their elegance and neatness.”

35 But however smooth and seamless the West’s boom appears almost two centuries later, such huge shifts in population centers, technology, wealth, and hierarchies were terribly stressful for ordinary people.

Anxiety

Mary Graham was a farm wife in Sudbury Massachusetts, struggling to make a go of it in the explosive local industrial economy. As she wrote to a friend in 1837: “Here we are all in comfortable health. L and myself have had to work as hard as we have been able, and a good deal harder than we wanted to I have shoes aplenty to bind, from 6 to 8 and 12 pairs a week—and with all the rest have got four as dirty, noisy, ragged children to take care of as any other woman, they look as though they would do to put out in the cornfields . . . to keep away the crows.”

Life was hard in an economy without safety nets, but she had her health and wrote in good humor. There was no humor in a letter she wrote seven years later: “Some news not very pleasant to me . . . Lucius has sold us out of house and home with the privilege of staying here until the first of June. If he can rake and scrape enough after paying his debts to set his family down in Wisconsin he is determined to go. So you wonder that I feel sad. Nothing but poor health and poverty to begin with in a new country looks dark to me.”

36She had much to fear. Trollope especially noted how drawn, tired, and lonely western farmwives looked, and she also understood that, high nutrition notwithstanding, the population was sick. For all its attractions, the riverine West was a sink of malaria. One farmwife who “seemed contented, and proud of her independence” conceded “that they had all had ague in the fall.”

37Trollope was a great walker and loved getting out of Cincinnati with her children to enjoy the scenery around the river or to picnic at a cherished woodland glen with a small waterfall.

It was indeed a mortifying fact, that whenever we found out a picturesque nook, where turf, and moss, and deep shade, and a crystal stream, and fallen trees, majestic in their ruin, tempted us to sit down, and be very cool and very happy, we invariably found that the spot lay under the imputation of malaria....

We had repeatedly been told, by those who knew the land, that the second summer was the great trial of health of Europeans settled in America. . . [and] I was now doomed to feel the truth of the above prediction, for before the end of August I fell low before the monster that is for ever stalking through that land of lakes and rivers, breathing fever and death around.

38The “ague,” a debilitating fever attack that is a symptom of malaria, often recurs throughout one’s life. Trollope’s first bout kept her in bed for nine weeks. The following year, not long after she had left Cincinnati and was anxious to start her book, the ague returned and “speedily brought me very low, and though it lasted not so long as that of the previous year, I felt persuaded I should never recover from it.” Her son Henry had contracted it as well.

39Social anxiety is often reflected in social unrest. On the East Coast, where employment relations were much more structured than in the West, there was a wave of strikes. The most famous were in New York, where “Workeyism,” akin to later European laborite political movements, showed its organizational power. The commercial sailors, the riggers and stevedores, the building laborers, the tailors, the coal heavers, the hatters, and other trades all went out on strike—often more than once. At times the port was completely shut down, and in 1836, the city was on the precipice of a general strike. The recession that followed the Jacksonian banking crises quelled labor unrest for a time, and the inundation of destitute, mostly unskilled, famine Irish, in all major eastern cities shifted the organizing focus to nativism.

40Outside of the major cities, anxieties were more likely to be expressed in revivalism. Charles Grandison Finney evangelized much of western New York in the 1820s, preaching a more user-friendly brand of Presbyterianism, emphasizing salvation through repentance. Finney was among the entrepreneurs of a newer, more professional, form of revivalism, all carefully choreographed and marketed—with advance men, handbills, and arrival parades. Revivalism intersected with Temperance drives, and together harkened back to Jeffersonian notions of a republic of sober, stalwart, independent, virtuous, farmers and mechanics.

Especially in the West, Methodist and Baptist circuit riders mastered the camp-meeting revival form, turning it in into a welcome mode of mass entertainment like a rock concert, as well as a splendid release valve for mass anxiety.

41 Our reporter Frances Trollope was on the scene. She had “long wished” to attend a camp meeting and jumped at an invitation to accompany “an English lady and gentleman” in their carriage, to a “wild district in Indiana” finding themselves among a great crowd of curious spectators that mixed with the faithful.

42They “reached the ground about an hour before midnight,” parked their carriage in care of a servant, and made their way through three circles of fire and tents. There were fifteen preachers in attendance; they would preach in rotation from Tuesday through Saturday. No one was preaching outside when Trollope and her party arrived, but “discordant, harsh, and unnatural” sounds were coming from the tents. They entered one and saw “a tall grim figure in black . . . uttering with incredible vehemence an oration that seemed to hover between praying and preaching.” The circle of people kneeling around him responded with “sobs, groans, and a sort of low howling inexpressibly painful to listen to.”

“At midnight a horn sounded through the camp,” and people flocked from all over to the central preacher’s stand. Trollope and her hosts estimated that there were about 2,000 people in attendance, and they found a place right next to the preacher’s stand. A space in front of the stand was called “the pen,” and after a harangue that “assured us of the enormous depravity of man,” one of the preachers invited “anxious sinners” who wished “to wrestle with the Lord to come forward into the pen.”

ayWhen few people moved to come up, the preachers came down to the pen and began to sing a hymn.

As they sung they kept turning themselves round to every part of the crowd, and by degrees, the voices of the whole multitude joined in chorus. This was the only moment at which I perceived any thing like the solemn and beautiful effect, which I had heard ascribed to this woodland worship. It is certain that the combined voices of such a multitude, heard at dead of night, from the depths of their eternal forests, the many fair young faces turned upward, and looking paler and lovelier as they met the moon-beams, the dark figures in the middle of the circle, the lurid glare thrown by the altar-fires on the woods beyond, did altogether produce a fine and solemn effect, that I shall not easily forget.

But soon the “sublimity gave way to horror and disgust,” as Trollope was fascinated and repelled by the undertone of sexuality:

Above a hundred persons, nearly all females, came forward, uttering howlings and groanings, so terrible that I shall never cease to shudder when I recall them . . . and they were all soon lying on the ground in an indescribable confusion of heads and legs. They threw about their limbs with such incessant and violent motion, that I was every instant expecting some serious accident to occur....

Many of these wretched creatures were beautiful young females. The preachers moved among them, at once exciting and soothing their agonies. I heard the muttered “Sister! dear sister!” I saw the insidious lips approach the cheeks of the unhappy girls; I heard the murmured confessions of the poor victims, and I watched their tormentors, breathing into their ears consolations that tinged the pale cheek with red.... I do [not] believe that such a scene could have been acted in the presence of Englishmen without instant punishment being inflicted.

Eventually, “the atrocious wickedness of this horrible scene increased to a degree of grossness, that drove us from our station.” Trollope and her friends repaired to their carriage to snatch some sleep (on beds prepared by the servant) and “passed the remainder of the night in listening to the ever increasing tumult at the pen.”

But as morning broke, the show-business aspect of it all began to dawn:

The horn sounded again, to send them to private devotion; and about an hour afterward I saw the whole camp as joyously and eagerly employed in preparing and devouring their most substantial breakfasts as if the night had been passed in dancing; and I marked many a fair but pale face, that I recognized as a demoniac of the night, simpering beside a swain to whom she carefully administered hot coffee and eggs....

After enjoying an abundance of strong tea, which proved a delightful restorative after a night so strangely spent, I wandered alone into the forest, and I never remember to have found perfect quiet more delightful.

Trollope camp meeting. Lithograph by August hervieu .Trollope is in the foreground (with illuminated bonnet). Hervieu is behind her with his sketch pad. Note the discreet distance maintained by trollope’s entourage from the scene before them.

43

The Coming of the Railroads

Steamboats did an effective job of tying together the interior of the country west of the Alleghanies, but as the Erie Canal had shown, the real bonanzas came from linking the West with the eastern seaboard. Chicago, Cleveland, and New York could be linked by water, but common-carrier transportation from interior cities like Pittsburgh and Baltimore would have to cross some formidable mountains; all skeptics notwithstanding, that required railroads.

Canals and railroads are both forms of low-friction transportation and were much in competition in the first third or so of the nineteenth century. “Low-friction” also includes horse-drawn trolleys, which were common in nineteenth-century cities. One of the earliest of commercial railroads, the Baltimore & Ohio (B&O), was horse-drawn during its first couple years of operation but switched to steam in 1830. The cost and difficulty of constructing canals and railroads were not greatly different,

az44 but railroads were generally much faster and therefore came to be preferred by passengers.

Great Britain had used steam locomotives in mines from the early 1800s, but the two countries got off to a roughly neck-and-neck start in commercial railroads. George Stephenson opened the first commercial British railroad, the Stockton and Darlington, in 1825. The first commercial steam railroad in the United States commenced operating either in 1828 or 1829. The first American railroad entrepreneurs bought their engines from Great Britain, but British engines were designed for the highly engineered British rail system, with its heavy tracks, level runs, and minimal curves. They destroyed American tracks and were easily derailed.

45 Robert L. Stevens, head of the Camden and Amboy, invented the T-rail, which still prevails today. It’s easy to lay and very durable. A New York engineer, John Jervis, invented the rail-hugging swivel carriage for the front of the locomotive. Even in the mid-1830s, Jervis’s engines could routinely hit sixty miles per hour. Also by then, American locomotives had acquired their bell-shaped stacks—to reduce the flying sparks from wood-fueled engines—and the cowcatchers, which allowed killing a cow without a derailment. They were also the first to incorporate lighting—at first just a fire-bearing cart pushed in front, later replaced by a kerosene lamp with a mirror to project a beam.

46

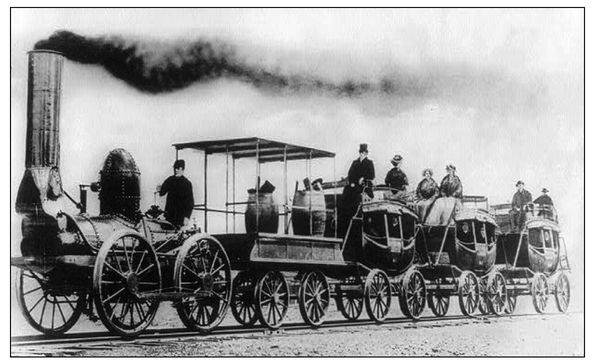

The deWitt Clinton Locomotive. The deWitt Clinton was the first steam locomotive to run in New York state, in 1831, on the Mohawk and Hudson line between Albany and Schenectady, a run of sixteen miles.

Harriet Martineau traveled by one of the first train lines in the South. She took an overnight stage to Columbia, some sixty miles, to meet a train due to arrive at eleven the next morning, which would take her to Charleston, another sixty-two miles, in time for dinner. The carriage hit a stump and was very late, but the train had had its own minor accident and was even later, so the passengers still had a several-hour wait. Martineau wrote:

I never saw an economical work of art harmonize so well with the vastness of a natural scene. From the piazza [where they were waiting] the forest fills the whole scene, with the railroad stretching through it, in a perfectly straight line, to the vanishing point. The approaching train cannot be seen so far off as this. When it appears, a black dot marked by its wreath of smoke, it is impossible to avoid watching it, growing and self-moving, till it stops before the door....

For the first thirty-five miles, which we accomplished by half-past four, we called it the most interesting rail-road we had ever been on. The whole sixty-two miles was almost a dead level, the descent being only two feet. Where pools, creeks, and gullies had to be passed, the road was elevated on piles, and thence the look down on an expanse of evergreens was beautiful....

At half-past four, our boiler sprang a leak, and there was an end to our prosperity. In two hours, we hungry passengers were consoled with the news that it was mended. But the same thing happened again and again; and always in the middle of a swamp, where we could do nothing but sit still....

After many times stopping and proceeding, we arrived at Charleston between four and five in the morning; and it being too early to disturb our friends, crept cold and weary to bed, at the Planter’s Hotel.

47Despite a wild English railroad-building bubble in 1845–1848, the United States quickly outstripped the United Kingdom in total rail mileage.

The construction boom of the 1850s was nothing short of stupendous. Mileage increased by half in New England, doubled in the Middle Atlantic states, quadrupled in the South, and increased eightfold in the West. By 1860, the West was becoming the center of gravity of the national population and had the greatest extent of railroad mileage. Locomotives got much bigger, faster, and more complex, while bridge builders like John Roebling achieved new milestones in suspension bridge technology, as in his Niagara River Suspension Bridge connecting the United States and Canada, which was opened to train traffic in 1855.

| Railroad Miles in Service48 |

|---|

| Year | United Kingdom | United States |

| 1840 | 1,650 | 2,760 |

| 1850 | 6,100 | 8,600 |

| 1860 | 9,100 | 28,900 |

A concerted national program of internal improvements, with a heavy focus on transportation to knit the country together, had long been the dream of Henry Clay and the Whigs. Jefferson himself had favored turnpike and canal building, but Andrew Jackson had put an effective end to federally supported internal improvements with a famous 1830 veto, incidentally foregoing the opportunity to establish national standards for items like road gauges (track widths) to ensure connectivity.

49Trollope visited Washington as the debate over internal improvements was at its zenith, and attended several of the debates: “I do not pretend to judge the merits of the question. I speak solely of the singular effect of seeing man after man start eagerly to his feet, to declare that the greatest injury, the basest injustice, the most obnoxious tyranny that could be practised against the state of which he was a member, would be the vote of a few million dollars for the purpose of making their roads or canals; or for drainage; or, in short, for any purpose of improvement whatsoever.” A few days later, she witnessed the elaborate funeral cortege of a deceased congressman and learned that all members were entitled to be “buried at the expense of the government (this ceremony not coming under the head of internal improvement).”

50The practical effect of the improvements veto was that extensive development of the roads was almost always a combined public-private enterprise, with private investors contributing equity, while the states sold revenue bonds and facilitated the assemblage of the necessary rights-of-way. One of the most ambitious of the early projects was a hybrid Philadelphia-Pittsburgh connection largely financed by the state of Pennsylvania and comprising canals on either side of the Alleghanies, with a “Portage Railroad” to cross the mountains. When it opened in 1834, a traveler could board a train in Philadelphia and proceed 82 miles by rail to Columbia, on the Susquehanna River; shift to a canal boat for 176 miles to Hollidaysburg, near Altoona; then cross the Alleghanies to Johnstown via a series of wooden inclined planes, with an average slope of about 10 percent. The distance of the traverse was 36 miles as the crow flies, with railcars pulled up by stationary steam engines on the ascent and coasting free on the downslope. Johnstown was the terminus for a final 104-mile canal connection directly into Pittsburgh. The highest point on the Portage road was 2,300 feet above sea level, and the vertical distance of the ascent and descent on the inclined planes were 1,100 and 1,300 feet respectively.

51Dickens took that route on his trip west and wrote, “Occasionally the rails are laid upon the extreme verge of a giddy precipice; and looking down from the carriage window, the traveller gazes sheer down, without a stone or scrap of fence between, into the mountain depths below.... And it was amusing, too, when . . . we rattled down a steep pass, having no other moving power than the weight of the carriages themselves.” One enterprising sailor took a boat from eastern Pennsylvania via river and canal to the Portage Road and, after it had been hauled to Johnstown, sailed all the way to New Orleans.

52The Portage road cut the cost of moving goods across the mountains to a fourth the cost of the old wagon routes. But it was never a financial success, in large part because it was very expensive to maintain and to staff. The frequency of “breaking bulk” was also an annoyance. Merchants of the day took for granted that they had to unload and reload their goods at each change of railroads, or from railroad to canal boat. But the Portage road required reloading at each new inclined plane—ten times altogether at each crossing. In 1854, the state sold the road to the Pennsylvania Railroad, a private entity that the state had taken the lead in organizing in 1846. It began working on an Alleghany rail crossing shortly after it was incorporated, even as it consolidated dozens of smaller roads on both sides of the mountains and forged the links required to supplant the old canal legs of the journey. The unified Philadelphia-Pittsburgh rail line opened in 1855, a two-track road completed according to the high engineering standards the Pennsylvania became famous for. The most striking engineering feature was the Summit Tunnel, 3,600 feet long, running through the summit of the highest mountain traversed, about 200 feet below the peak. The construction required four shafts, two of them 300 feet deep. Winter operating conditions were sufficiently severe that the western tunnel portal was fitted with doors that were opened only for a train passage.

53Elsewhere, line development was rather more harum-scarum, although often punctuated with feats of virtuosic engineering. The Erie, completed in 1851 and linking New Jersey’s Hudson River piers to Lake Erie and the West, may be the best example.

The Erie’s slogan was “between the Ocean and the Lakes,” and when it opened, it was the longest continuous train route in the country. The construction had taken almost twenty years, and completion came only months shy of exceeding a twenty-year franchise limit that would have triggered a reversion of the railroad to the State of New York, which could have sold it to the highest bidder.

It was a challenging route, wending through the Catskill and Pocono mountains, necessitating ravine-spanning bridges and difficult cuts and grading through granite terrain. Most impressive, perhaps, was the Starrucca Viaduct, consisting of Roman-style stone arches, 1,090 feet long, 25 feet wide, and between 90 and 100 feet high. When asked if he could build it, an engineer affirmed that he could, and could finish on time, “provided you don’t care what it costs.”

54 But the true miracle was navigating the shoals of politics and finance in a notoriously corrupt age, while fending off Wall Street’s banditti. For comparison, the transcontinental railroad authorized by Congress the next decade was completed in about one-third the time, even though it crossed the Rockies.

There were multiple close calls. Several times the planned route turned out to be impassable, and by pure luck, another acceptable path was found.

55 And the road was often on the verge of bankruptcy. At one of the darkest moments, in 1846, the company was running out of money, the British were ratcheting up the price of the line’s iron rails, and late British deliveries were making the completion deadline unattainable under almost any circumstances.

The rescue came from two brothers, George and Selden Scranton, who ran a floundering little iron business—a furnace, a forge, and a rolling mill—in the woods of northern Pennsylvania. The Scrantons volunteered to supply the rails, a product they had never manufactured, for slightly more than half the British price. The Erie gambled on the Scrantons, and they somehow produced adequate rails on schedule, hauling them as much as sixty miles through the forest. The Scrantons’ precarious iron venture, relocated to Lake Erie and dubbed the Lackawanna Iron and Coal Company, became a major industry player in the second half of the century. Their coal business remained in Pennsylvania, and the village near their woodland factory is now the city that bears their name.

56Actual completion of the line was decidedly a matter for celebration, in an era that had grandiloquent tastes for such doings. The main event was a train trip from the railroad’s Hudson River docks to Dunkirk, the small town on the southern shore of Erie that served as the line’s western terminus. A two-train excursion party included President Millard Fillmore, who was born in the lake region and had practiced law in Buffalo; Secretary of State Daniel Webster; other members of the cabinet; presidential hopefuls like William Seward and Stephen Douglas; executives and bankers of the railroad; and nearly three hundred other notables.

The party assembled on May 13 at the Battery at the southern tip of Manhattan and moved in stately procession to city hall, where they were entertained by multiple military marching bands and hours of speechifying. Promptly at six the next morning, they reassembled at the Battery for the twenty-five-mile steamboat ride to the Erie terminal at Piermont, New York. There they disembarked and were directed to two trains leaving just five minutes apart. Remarkably, both were actually underway only a few minutes later than the scheduled departure.

57The steamboat trip was necessitated because some years before, the directors had inexplicably passed up an offer from the tiny Hudson and Harlem Railroad for an inexpensive direct rail link into the city—a mistake that dogged them for the next century, not least because of the necessity to break bulk on arriving at the Hudson and restow goods on a freight ferry. Another catastrophic decision was to use the six-foot British rail gauge, when most American lines were standardizing on a gauge of four feet, eight and a half inches. The wider bed increased the labor of cutting track beds in granite, the heavier trains burdened bridge building, and it cost many millions to finally bring the Erie to standard a half century later. The choice of the British gauge was both intentional and utterly wrongheaded, for it was expressly intended to make it difficult for other lines to connect with the Erie—to its great disadvantage as the national network steadily integrated after the Civil War.

58The celebratory trip itself came close to fiasco. Almost as soon as the train reached steeper terrain, the first engine proved inadequate to its load. (There had been a bitter factional argument over engines within the engineering staff.) After a considerable delay, the second train’s engine was linked to the rear of the first, which solved the problem. According to the testimony of the conductor, engineer, and several passengers, the trains then traversed a thirty-four-mile stretch from Port Jervis to Narrowsburg in just thirty-five minutes, an extraordinary speed for the time. Some passengers were sufficiently alarmed to leave the party. Webster must have had the ride of his life. To get a full view of the scenery, he had insisted on riding in a rocking chair tethered to a flat car, protected only by a steamer blanket and a bottle of rum.

59In the event, the party reached Elmira, 283 miles from New York within minutes of the scheduled 6:09 PM arrival time. They were greeted there with a seven-hour banquet but were off again the next morning at 6:30 and arrived at the scheduled 1:45 PM at Dunkirk, where they tucked into yet another enormous meal. The bill of fare was preserved for posterity: “Chowder, a yoke of oxen barbecued whole, 10 sheep roasted whole, beef a la mode, boiled ham, corned beef, buffalo tongues, bologna sausage, beef tongues (smoked and pickled), 100 roast fowls, hot coffee, etc.”

60The broad outline of the modern railroad network east of the Mississippi was more or less in place by 1860. There were four large east-west networks. Two originated in New York: the Erie and Cornelius Vanderbilt’s New York Central, an 1850s consolidation often connecting roads. Both the Pennsylvania and the B&O offered through service to Pittsburgh and beyond from Philadelphia and the Chesapeake region respectively. The outline of a rail network emanating from Chicago was in place, with multiple connections both with the four east-west lines and to Cincinnati, St. Louis, and most other western cities besides.

American development was still very inconsistent, much like the quality of its trains, but the breadth and power of the economic surge was unmistakable. But if British investors seemed almost irresistibly drawn to American bonds, elite British opinion remained dismissive of “Jonathan’s” pretensions.

Two other European travelers visited the United States shortly before Trollope did. One, a British military man and travel writer, had the same caustic tone as Trollope but with none of her natural empathy. He was especially entertained that the New York legislature consisted “chiefly of farmers, shopkeepers, and country lawyers, and other persons quite unaccustomed to abstract reasoning.” Unlike Tocqueville, he did not believe the middle class could run a country. A German traveler, Duke Bernhard of Saxe-Weimer-Eisenach, like Tocqueville a noble from one of the most royal European lines, was critical of a great deal of what he saw, especially in the South, but much more favorably impressed than British travelers.

A British journal reviewed the two books together in 1829 and decided that the German’s views could only be accounted for by the fact that most of his previous travels had been on the continent: “The rapidity of the progress made in [America] must be the more striking to one who compares them, as the Duke would do, with the cities [on the continent] . . . than to a native of Great Britain.... So the differences between our two authors may be easily accounted for by the different tenours of their previous experiences and habits.” The reviewer concluded happily that there is “nothing in [America] . . . to excite envy or jealousy.”

61