CHAPTER EIGHT

The Newest Hyperpower

THE 1886 BLOOMINGDALE’S CATALOG—160 PAGES, STUFFED WITH SOME 1,700 products, from ladies’ corsets to pistols—advised its clients to send a follow-up inquiry if they had not received an order confirmation within ten days after they had posted it, but to allow fifteen days if they lived on the Pacific Coast. Consider the billions of investment that underlay that offer. Just twenty years before, at the end of the Civil War, there had been only a few hundred miles of railroad track west of the Mississippi. Even in the 1870s, vast regions of Bloomingdale’s 1886 catalog market had been reachable only by wagon train. But by 1886, the backbone of the national rail system was already in place, along with fast-freight forwarding companies, telegraph-based delivery tracking and financial settlement systems, insurance, and newly invented bills of lading that guided a delivery through the railroad maze.

And therein lies the secret of the American surge in per capita growth. It wasn’t advanced technology. Throughout the nineteenth century, Americans were students to the British in steelmaking and most other science-based industries. Where the Americans wrote the rulebook, however, was in mass production, mass marketing, and mass distribution. The great nineteenth-century American economic invention, in short, was the first mass-consumption society. The invention proceeded in stages. The first was to create the infrastructure for a continent-wide, first-class economic power.

1

Infrastructure

Railroads and the telegraph were symbiotic businesses. The roads offered clear graded routes for stringing telegraph lines, and station managers conveniently doubled as telegraph operators; the benefit for the roads was that the telegraph, for the first time, allowed them to track and manage their far-flung freights and rolling stock.

There were other, less obvious symbioses. The western railroads were typically built far ahead of traffic—“If You Build It, They Will Come.” The roads benefited from both state and federal land grants in wide swaths on both sides of their tracks. In order to create future freights, they frequently transferred their land to farmers on highly advantageous terms. Much of the early risk capital came from the British, who regarded American railroad bonds as the equivalent of today’s high-yield paper: defaults were to be expected, but the returns were still attractive. So the railroads opened the great American grain belt west of the Mississippi, and innovative factory-farmers created a Saudi Arabia of food.

It was a prodigious accomplishment but deeply flawed: thousands of miles of track were poorly constructed, curves were dangerous, bridges flimsy. Even today’s takeover titans might be embarrassed at the reckless financial leverage at many of the lines. Speed to completion and revenue collection were the constant imperatives. Leverage drove behavior in other ways. With huge volumes of shares and bonds in play, takeover battles raged around nearly all the lines, exhausting the resources of courts and grinding up investor dollars. The takeover wars were yet another accelerant for the track laying: you achieved local dominance, and earned the cash for debt service, by controlling access to all the prime business centers. So expansions proceeded in a series of flanking and counterflanking lurches. Chaotic as it was, the rails and their piggy-back telegraph lines pulled together the country commercially. The country had less than 9,000 miles of track in 1850, nearly 50,000 miles by 1870, and 164,000 in 1890. By 1910, the national rail network, with 240,000 miles, was roughly the one we have today.

At least four major industries were enabled by the railroads: factory farms, meatpacking, steel, and petroleum.

BONANZA FARMS

Jay Cooke may have been the most respected banker in the country, until the insolvency of his Northern Pacific railroad precipitated the Great Crash of 1873.

2 In 1873–1874, more than one hundred railroads failed financially. All of them had borrowed too much, built too far ahead of customers, and couldn’t pay their debt service and dividends. The Northern Pacific, however, had a valuable asset—some 39 million acres of federal land grants—and creditors often took land in settlement of their loans. The president of the Northern Pacific, George Cass, had the idea of organizing the absentee owners’ lands into productive farms; he hoped the new freights would reinvigorate the line. He tapped as his manager a failed farmer-entrepreneur and Yale graduate, Oliver Dalrymple. Dalrymple’s attraction was that he was a visionary who had failed in a promising way—he had run out of capital trying to transform the nature of farming.

Cass provided the capital and the steady hand, while Dalrymple laid out an industrial-style, multiyear production schedule, which included sod busting and plowing 5,000 acres of land each year, with specific land-improvement and planting schedules thereafter. The whole idea would have been infeasible before the advent of quality steel plow blades to cut through the thick tangle of prairie grass roots. Harrowing, seeding, harvesting, threshing followed in quasi-military sequence, and the land was replowed before freezing set in. By the 1890s, gang plowing was being executed with seventy-horse plow teams arrayed in a 45° angle to the plowing line, so the lead team could lead a great wheeling maneuver at the end of each mile-long run.

Dalrymple’s first producing parcel, in 1878, had 126 horses, eighty-four plows, eighty-one harrows, sixty-seven wagons, thirty seeders, eight threshing machines, and forty-five binders. By the 1881 harvest, with thirty-six threshers, he was loading three freight-car loads, or 30,000 bushels every day—at an average cost of 52 cents a bushel in a market that was paying $1. That’s why they were called “Bonanza” farms. By 1890, American wheat farms west of the Mississippi were producing about 30 percent to 50 percent of the Western world’s supply, incidentally jump-starting the Minneapolis flour milling industry. The Pillsburys were among the first to construct modern, mechanized, flow-through flour milling plants and underwrote many of the railroad extensions into Minnesota.

3

CHICAGO MEATPACKING

Consumers were accustomed to eating salted pork in the form of bacon and hams, but beef consumers preferred their meat fresh. Since the largest markets for fresh beef were in the East, so were the herds. Unfortunately, they were concentrated in the Southeast and were decimated during the Civil War. Entrepreneurs noticed that the seemingly limitless Texas grasslands were full of semiwild longhorns, and European capital flowed into big-ticket ranching. Barbed wire was the critical invention. The XIT ranch, organized in the mid-1870s with 3 million acres and 6,000 miles of barbed wire, was the largest in American history. At first, the cattle had to be driven to train connections in Abilene for delivery eastward to local slaughterers. Within about twenty years, thickening train connections in cattle country consigned the romance of the cattle drive to the pages of dime novels.

Shipping dressed meat was obviously cheaper than shipping steers, but the distances required refrigerated railroad cars. Various experiments with ice-packed cars were unsatisfactory until Gustavus Swift, a Massachusetts butcher, added a forced-air circulatory system. But he was stonewalled by the railroads, which had invested heavily in new fleets of cattle cars and expensive stockyards and watering sites. Swift scraped up enough money to finance ten cars for a Canadian railroad line and started delivering fresh beef to Boston. The transport savings allowed him to undersell the local slaughterers and still book very high profits. He plowed the profits into expansion and started selling fresh “Western Beef” up and down the East Coast. The railroads dropped their opposition, and within just a few years, meatpacking was concentrated in Chicago, where it quickly sorted down into four or five major houses, most of which consolidated vertically into stockyards, ranches, and distribution centers, with American beef transshipping as far as Tokyo and Shanghai.

4

STEEL

Western railroads required steel rails to support their high speeds and heavy freights, but when the postwar railroad boom got underway, American mills still did not mass-produce quality steel, so the roads used British rails. Steelmaking was an ancient craft. The high-carbon iron that emerges from a blast furnace is suitable for casting into stove plate, anvils, and the like but is very hard and brittle. Easy-to-work malleable or wrought iron was created by removing all the carbon, usually by puddling, a tedious craft process. Steelmakers recarburize the iron just enough to hit a sweet spot between hardness and malleability.

Alexander Lyman Holley, scion of the Salisbury Holleys and son of Alexander Hamilton Holley, the forge owner, edge-tool maker, and Connecticut governor, almost single-handedly dragged America into the steel age. As a young man, Lyman negotiated iron contracts with Springfield’s Roswell Lee, frequently visited the Collinsville Axe works, and counted Sam Collins’s son among his close friends. Graduating from Brown with an engineering degree, he went to work for George Corliss and then, though still young, shaped a career as an engineering consultant and a science journalist, focused on machinery and metallurgy. A brilliant draftsman and a fluent writer, he was a regular in the pages of the

New York Times and the editor of several technical journals. On a European trip studying ordnance, he encountered the Bessemer process that had revolutionized British steel production, and arranged with Bessemer to act as his American agent. That required mediating substantial patent challenges, which were resolved by the formation of a patent-pooling trust to oversee compliance and collect royalties.

bs

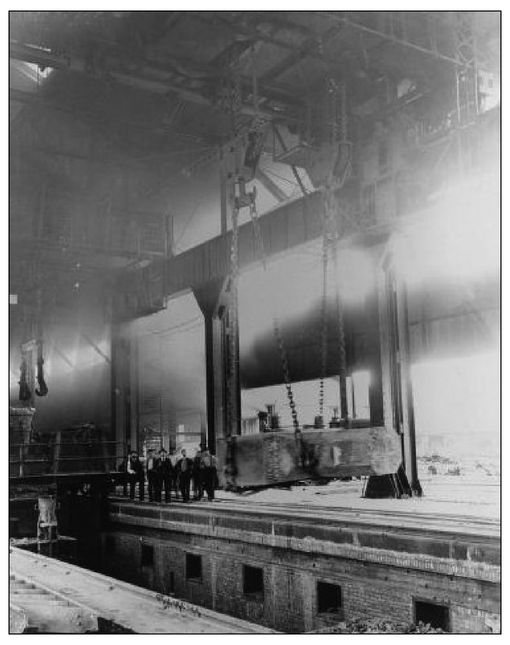

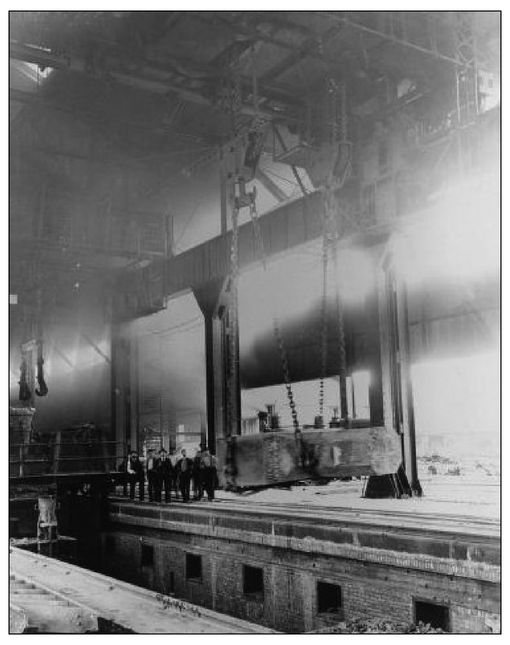

90-ton Ingot. By the end of the nineteenth century, American steelmakers, led by Carnegie Steel, had far surpassed the British in total steel production, and with the exception of some specialty products could match the British in steel quality. The picture shows a 90-ton steel ingot poured at the Carnegie Homestead plant in 1892.

Holley then designed most American steel plants. Of the eleven Bessemer plants in America, six were entirely his design, on three others he was a design consultant, and the remaining two were copies of his other plants. His signature piece was Andrew Carnegie’s Edgar Thomson plant, the ET, near Pittsburgh. Opening in 1875, it was the first Holley was able to build from scratch, and he made it a model of continuous-flow processing. Pig iron was melted in twelve-ton cupolas and poured directly into a giant Bessemer converter. After the conversion had been completed, the converter was tipped and poured the steel into a moving train of ingot molds on an internal rail. The rail system transported the ingots to cutting and trimming machinery and then to mechanical rail rollers, where they were “pressed with uniformity and precision . . . by hydraulic fingers [and therefore] . . . cool almost perfectly straight,” which Holley contrasted to hand straightening “which cannot, of course, be precise and uniform.”

5Subordinating the plant design to the requirements of the internal work flow was a Holley mantra. At the ET, the plant was “a body shaped by its bones and muscles, rather than a box into which bones and muscles had to be packed.”

6 Work-in-process always moved from one station to the next by rail, loading and unloading was always mechanical, and the direction of loading was always down. Other innovations, like snap-out converter bottoms for brick relining, were all designed to maximize production uptime.

Integration was pushed much further just a few years later, when the blast furnaces that smelted iron ore were moved to the steel plant. The new iron was then charged directly from the furnaces into the Bessemer converters, eliminating the necessity of transporting and remelting the pig—a step akin to Paul Moody’s integration of textile spinning and weaving. Finally, the ET plant site was at the intersection of two rivers and two major rail lines, all with direct connections to the plant’s internal rail system to simplify loading and unloading.

Carnegie was America’s greatest steel tycoon. He had started as a telegraph boy at the Pennsylvania Railroad, working directly for Tom Scott, the boss of operations. He rose quickly as the fair-haired boy of both Scott and Edgar Thomson, the road’s president; along with Scott and Thompson, he grew rich by looting the company. The three formed a series of businesses headed by Carnegie, with Scott and Thomson as silent partners, selling sleeping cars, iron, bridges, and other gear to the Pennsylvania on preferential terms. Scott was nearly fired when the board discovered their game. Cut adrift, Carnegie cast about for a new career; on a trip to England, he visited its vast new Bessemer plants and saw his future.

Carnegie remained remote from the factory floor, although he loved to dabble in the details. His plants were run by a succession of great managers and steel technicians—“Captain” Bill Jones; Henry Frick, who had created the coke industry before joining Carnegie; and Charlie Schwab. But Carnegie was the ideal client for Holley. His management target was always market share, not profits, so he kept a laser focus on through-put, mechanization, and reduced manning—so-called hard-driving. Bill Jones, who patented a number of steelmaking processes, created a stir just six years after the ET opened by telling a meeting of British engineers that his plants got twice the output from a comparable converter as the British did. Holley, whom the British viewed as an honest broker, confirmed the claim. The secret wasn’t faster processing—the laws of physics determined that—but much less downtime.

As Carnegie’s market share grew, he acted as the industry price disciplinarian. If markets turned down, he was the first to cut price and increase share. By the mid-1880s, the industry’s rail-pricing standard hovered around the long-outdated tariff level of $28 a ton. (British export prices, pretariff, were about $33 a ton for rail-quality steel.) During a collapse in the rail market in 1897, Carnegie drove prices all the way down to $14 a ton to keep his plants running full, and

still made record profits. Elbert Gary, later the president of US Steel, observed that Carnegie had been on the brink of “driv[ing] entirely out of business every steel company in the United States.” By the time of the 1901 US Steel consolidation, Carnegie controlled about a quarter of American steel production, which was equivalent to about half the total British output.

7

STANDARD OIL

Far more than any other big American industry, the rise and dominance of American petroleum in the nineteenth century is the story of one company, Standard Oil, and one man, John D. Rockefeller. Rockefeller, from middle-class farming stock, started his career in dry goods and, in 1861, invested with his dry-goods partner in a new oil refinery in the booming new “rock oil” district of western Pennsylvania. Upon a firsthand inspection, he found the business so attractive that he took over as day-to-day manager. Four years later, he bought out his partners, opened his second refinery, and built oil-shipping facilities in New York. (About 70 percent of oil was exported from the earliest days.) From the start, Rockefeller seems to have envisioned the industry as a single, integrated, continuous-flow process operation from the wellhead to final user, and he moved directly and inexorably to make that a reality. By 1870, when he reorganized as the Standard Oil Company, he was already the biggest refiner in the world.

Rockefeller won his markets by concentrating fanatically on reducing costs and increasing efficiency. Refining was already developing a strong technical base, with good temperature controls, use of super-heated steam, much larger-scale equipment, and increased focus on capturing waste for useful by-products, like cold creams. After joining with the Pennsylvania’s president, Tom Scott, in a misconceived attempt to create an oil shipping cartel, Rockefeller quietly bought up nearly all of the other Cleveland refiners. He was never a haggler and was happy to pay premiums for transactional speed. Just showing a target Standard’s books was usually enough to close a deal, for no competitor ever came close to matching Rockefeller’s profit margins. Targets always had the choice of being paid stock or cash, and Rockefeller always recommended taking stock. Most opted for the cash; the ones who took stock and held on to it became very rich.

Once he owned all the Cleveland refiners, Rockefeller scrapped them all and built an entirely new refinery complex comprising six state-of-the-art production sites, each concentrated on a single distillate for processing efficiency. (Kerosene for lighting dominated sales in the nineteenth century, but there were also lucrative markets in lubricants, naphtha, benzene, and other distillates.) The new plant equated to about a quarter of the country’s refinery capacity and was almost certainly the most efficient. At roughly the same time, Rockefeller began to take over the major railroads’ oil collection, loading, and dock facilities. He also generally stood ready to finance upgraded tank cars or help fund important line extensions, and he was willing to guarantee shipping volumes in return for lower shipping prices.

With the Cleveland consolidation behind him, Rockefeller quietly proceeded to take over almost all the rest of the nation’s refineries. It happened very fast. Rockefeller simply visited each of the top regional refineries, in New York, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and Baltimore, and nearly all of them agreed to merge with Standard. These were all powerful businessmen, with giant egos, who had built nearly the same scale of operations Rockefeller had. But without any obvious strife they joined Standard under Rockefeller’s leadership, dramatic testimony to the power of the Rockefeller personality at first hand.

All of the acquisitions were executed in secrecy—there were no laws about such things in the 1870s. They all kept their names and current executives, but they all took strategic direction from Rockefeller. With Standard’s coffers behind them, they all stepped up the pace of acquisitions within their own operating regions, again with few signs of the changes afoot. The immense consolidation became known only in 1879, when Henry Rogers, a Standard distillation expert, was asked during congressional testimony to estimate the share of national refining capacity owned by Standard Oil. He thought for a minute and guessed that it was “from 90 to 95% of the refiners of the country”—as jaws dropped throughout the hearing room.

8Standard’s global near monopoly was not challenged until the mid-1880s, when the Nobel brothers’ Russian Baku fields began exporting into Europe. But it was still in a class by itself. From 1887 through 1896, Carnegie’s collection of steel, iron, iron ore, coke, and related businesses earned a cumulative $41 million; over the same period, Standard Oil earned $189 million, about four and a half times as much.

Rockefeller and Standard played very rough when they were building their franchise. Doing business in nineteenth-century America was much like selling airplanes in today’s Middle East. Bribing local officials was standard practice, and there is at least one documented instance in which Rockefeller clearly committed perjury on a witness stand. But the broader story that Rockefeller’s Standard Oil won its position by “secret railroad rebates” and other illegal monopolistic practices has little basis. The United States had no laws against railroad rebates or monopolies when Rockefeller was building his business, and claims by the contemporary muckraker Ida Tarbell and many subsequent Rockefeller biographers that they were “against the common law” are not supported even in the Supreme Court’s 1911 decision breaking up the company.

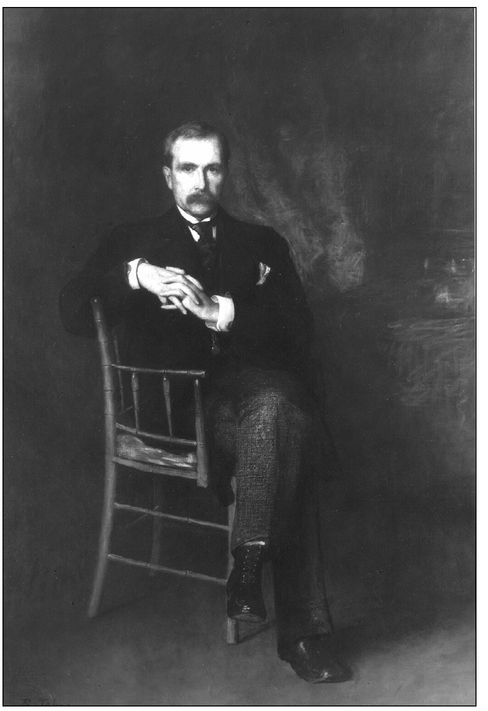

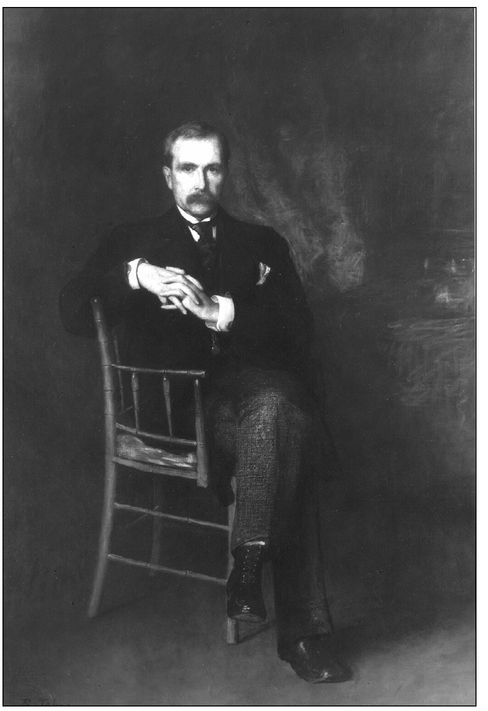

John D. Rockefeller. This portrait of Rockefeller was painted when he was in his fifties and at the height of his powers. It captures some of the powerful aura that for several decades allowed him to utterly dominate a major industry without, it seems, ever raising his voice.

Once Rockefeller eased out of day-to-day management by about 1895, “administrative fatigue” seems to have set in at Standard.

9 John Archbold, Rockefeller’s successor, visibly began to monetize Standard’s position. Equity returns jumped about two-thirds, from the rather modest average 14.3 percent in Rockefeller’s day to 24.4 percent under Archbold. As the company lost its entrepreneurial aggressiveness, its refinery market share dropped to only about 65 percent. Standard was also late to recognize either the opportunities in gasoline or the threat that electricity posed to its kerosene franchise. The 1911 Supreme Court decision mandating the breakup did Rockefeller a favor. Freed from the lassitude at the Trust headquarters, the thirty-four erstwhile subsidiaries almost all greatly improved their performance. Adjusted for inflation, their rocketing stock prices made Rockefeller possibly the richest man in history.

Rockefeller’s primary achievement was to create the world’s first global consumer product, with market shares in Europe, China, and Russia, akin to those in the United States. Hamlin Garland, writing of his hardscrabble childhood on a Great Plains farm, told of coming home from the fields in 1869 to the amazing transformation effected by a kerosene lamp on the table. Magazines like America’s Women’s Home extolled the advantages of a “student lamp” for late-night studying. The bright white light of the kerosene lamp, in every apartment and farm house, was a hallmark of modernity, just as the Standard Oil blue five-gallon kerosene can marked one of the earliest presence of modern markets in some of the remotest sections on earth.

The First Middle-Class Nation

Michael Spence is a New York University economist who has been studying the processes by which emerging markets, like Brazil and India, make the leap into the ranks of advanced countries. He suggests that there is a critical point he calls the “middle-income transition,” when a sufficient mass of the population become future-oriented, are able to plan and to save, and consciously set out to improve their positions. The United States, indeed, may be one of the few nations that was middle-class from the start.

bt The act of emigration itself suggests the presence of Spence’s middle-class mind-set. Tocqueville may have been the first to use the term “middle-class” in this sense, and Trollope was continually struck by the striving, go-ahead impulse among her midwesterners. Nobody they encountered, other than Southern slaves, reminded them of the peasants of England and France.

A key feature of a middle-income transition is the shift from infrastructure spending to consumer-oriented production. That transition was in full blast in the United States by the 1880s. Underlying the shift was the country’s pervasive social mobility. The very bottom and very top layers were probably more stable than Tocqueville believed, but the top ranks were far from impenetrable. Cornelius Vanderbilt, Andrew Carnegie, and John Rockefeller all came from modest backgrounds. Mobility was especially high within the middle three quintiles, probably higher than anywhere else. A number of studies show quite high rates of farm laborers becoming farm owners, blue-collar workers becoming managers, and countinghouse clerks rising to very senior positions.

10Real incomes grew steadily after the 1873–1874 recession and continued to grow through the 1880s, and it was reflected in people’s housing. The typical house got bigger and, in urban areas, was separated from the workplace, becoming a locus of family bonding after the day’s activities. In other words, it became a “home.” On farms as well, farmhouses evolved from a family factory into a civilized retreat from the animals and the odors. With the opening of the Brooklyn Bridge in 1883, Brooklyn became a bedroom suburb of Manhattan, and the “lunchroom” dotted the business district.

The midwestern “balloon” house, a wooden self-supporting frame hung with weather-proofing walls, became the American standard and may have inspired the steel-cage structure of the new office skyscrapers. Midwestern factories churned out machine-made doors and windows, and by the 1870s, machine-made mail-order kit houses were available in a wide range of prices and styles. Inexpensive, machine-made carpets and drapes and new methods of grinding paint pigments allowed people of quite modest incomes to add a touch of color or personal style to their home. Home spaces were divided into a semiformal parlor or sitting room, a dining room and a scullery, and bedrooms. Children increasingly had their own beds. Middle-class families regularly supplemented incomes by taking in boarders, who also supported the cost of household help.

The focus on the home space drastically changed the role of women, who became society’s officially designated civilizing force, arbiters of domesticity—“homemakers” who, as Harper’s noted, “legislate for our dress, etiquette, and manners without fear of veto.” Home economics, advice columns, home management, etiquette, and cookbooks proliferated. Being middle-class was a life strategy, a continuing campaign, mostly managed by women. Tactics included smaller families, more intense child rearing and education, budgetary management and savings plans, and training children in prudence and deportment.

The new respect for the purchasing power of women was reflected in the blossoming of the department store. The first establishment by that name was John Wanamaker’s, which opened in Philadelphia in 1876 as the “largest space in the world devoted to retail selling on a single floor.” Occupying a full city block in midtown, it was all about women. Lighted by a stained-glass ceiling by day and hundreds of gas lights by night, it was arranged in concentric circles, as much as two-thirds of a mile long, with 1,100 counter stools, so a lady could sit and discuss her purchase. Displays featured “Ladies’ Furnishings Goods,” “Gloves,” “Laces,” and “Linen Sheeting.” The 70,000 people who showed up on opening day were naturally almost all women, as were the counter assistants—although the lordly, formally dressed floor walkers were all male. The department store became a fixture in every sizeable city. New York had its Macy’s, Bloomingdale’s, Lord & Taylor, and B. Altman; Brooklyn its Abraham & Straus; Boston its Filene’s; Chicago its Marshall Fields; San Francisco its Emporium. Even much newer, rawer cities, like Detroit, Indianapolis, and Milwaukee had their Hudson’s and Gimbels.

Beneath the surface gloss, urbanization brought serious problems, especially in sanitation, which lagged population growth by several decades. Water-borne diseases like cholera and typhoid remained dangerous killers well into the twentieth century, accounting for a quarter of all infectious disease deaths in 1900. Wives, or servants, were still lugging water from pumps in the 1870s, but by the end of the decade most larger cities were piping (unfiltered and unchlorinated) water into homes in most of their residential areas. Privies were not connected to sewage systems. The backyard latrine—or in many working-class areas, the neighborhood latrine—gradually gave way to indoor toilets. Water closets, which flushed into a pit, were suitable for less settled areas, while urban designers experimented with a host of “earth closet” contraptions.

Many cities had gas lighting, at least in better neighborhoods, and almost everyone had a kerosene lamp. Over time, the expanding national wealth readily financed a great burst of municipal investment in clean water, sewers, garbage collection, transit, street lighting, police and fire services, and parks, stretching from the 1880s well into the twentieth century. Local water systems became a major market for Corliss’s big-ticket steam engines.

The clinching proof of the consumerization of America was the sudden explosion of brands. History had never seen a burst of new products like that in the America of the 1880s and 1890s. Store shelves offered Cream of Wheat, Aunt Jemima’s Pancakes, Postum, Kellogg’s Shredded Wheat, Juicy Fruit gum, Pabst Blue Ribbon Beer, Durkee’s salad dressings, Uneeda Biscuits, Coca-Cola, and Quaker Oats. Pillsbury and Gold Medal wiped out local flour millers. (Wives started buying cake mixes in the 1890s, but baking one’s own bread was still a badge of honor.) Advertising flourished right alongside. (N. W. Ayer, one of the first of the big advertising companies, got its start with John Wanamaker’s.) So Jell-O was the “quick and easy” dessert; Schlitz Beer was made with “filtered water”; Huckin’s soups were “hermetically sealed”; no human hands had touched Stacey’s Workdipt Chocolates. H. J. Heinz created a fifty-foot-tall electric pickle with 1,200 light bulbs in Times Square in 1896. The sign blinked Heinz’s “57 Good Things for the Table,” listing each one in lights. You’d “Walk a Mile” for a Camel and hum the jingle for Sunny Jim cereal. The Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company, A&P, was the first national grocery chain, and Frank Woolworth’s “nickel stores” swept through the country.

The speed of the branded-food triumph could have been due to the naïveté of consumers or perhaps to the execrable quality of local stores’ barrel food. One suspects it was both; nostalgia buffs too readily assume that consumers were fooled. Packaged brands brought people in much of the country their first access to more varied diets. Local grocers were often sinks of poor hygiene, bad storage conditions, adulteration, and outright misrepresentation (hog fat for butter). The packaged food industry had its own scandals, especially in meat, but safety and consistency were probably a great improvement over the general store.

A vast range of products made life simpler—Bissell carpet sweepers, Gillette “safety” razors with disposable blades, rubber boots and shoes, zippers, ice boxes (often with an opening on a house’s outer wall, so the iceman could fill it), Levi’s for workers. Or made life more fun: roller skates were a craze in the 1870s, bicycles in the 1890s. James Bonsack’s automatic cigarette-making machine went into production in James Duke’s factory in 1886. By 1900, Americans were buying more than 4 billion cigarettes a year, almost all of them from Duke, including still-current brands, like Lucky Strike. A pre-Duke cigarette maker invented the baseball card. Young women were discouraged from smoking but had a “mania” for cosmetics. Handbag stores prestuffed their bags with branded lipsticks and rouge. Helena Rubinstein and Elizabeth Arden, between them, dominated the business by the early 1900s. Household walls were festooned with chromolithographs: color facsimiles of American painters like Audubon, Bierstadt, and Winslow Homer. Currier and Ives were among the first to produce paintings specifically for chromolithography. Mark Twain’s Connecticut Yankee knows he is in a strange place because the medieval castle has no “chromos” on the walls.

Residential mail service triggered a postcard craze and then a greeting card craze. Postcards with photographic scenes were popular collectibles—one company produced 16,000 different views. Thomas Edison invented the phonograph in 1879, but Emile Berliner came up with the popular gramophone and the flat record in 1889; his system could make thousands of records from a single master. Versions of the modern juke box proliferated in the 1890s, and it was a natural accompaniment to the drugstore soda fountain—a pharmacist could pull in $500 worth of nickels a week. Both were an index of the increased leisure time of young people. Middle-class parents kept their kids in school, instead of sending them off to the factory, and were discovering that the demographic between child and adult was a previously undreamed-of species.

Home entertainment sales boomed—lawn tennis and croquet, board games, and stereoscopes. Two stereoscopic slides viewed in front of a light source produced a three-dimensional scene. Millions of slides were produced—natural wonders, stories, religious matter. Oliver Wendell Holmes once boasted that he had seen more than 100,000 stereo views. George Eastman introduced the celluloid film roll for his Kodak in 1888. A Kodak-sponsored photography contest in New York in 1897 drew 26,000 people. By 1900, the country had more than 1.5 million telephones. Improvements in printing technology produced an outpouring of magazines, inexpensive novels, and city newspapers. Plant lighting made morning papers possible, and publishers pulled in readers with sports pages, comics, puzzles, women’s pages, and advice columns. Dorothy Dix’s column started in 1896. Professional entertainment—baseball, boxing, vaudeville, burlesque, Barnum’s circus—and the amusement park were fixtures even in smaller cities. The Ferris wheel at the 1892 Chicago Exposition was 264 feet high, each of its cars was larger than a Pullman coach, and the fully loaded wheel handled more than 2,000 people at a time.

The great investment banks that had financed the railroad and steel industries—J.P. Morgan and Jacob Schiff’s Kuhn, Loeb—were supplemented by newcomers like Goldman, Sachs, and Lehman Bros. They were mostly Jewish, ascended from the earlier urban “rag trade,” and provided industrial-scale financing for consumer industries, which the Morgans and the Schiffs did not understand. Julius Rosenwald, a true retailing genius, took operational command of a struggling Sears and Roebuck in 1895 and, through Goldman’s, launched the first-ever public stock offering in a retail company. The purpose of the offering was to finance a mechanized rail-and roller-based goods assembly and distribution system, not unlike those pioneered by Alexander Holley for the steel industry. By the turn of the century, virtually every consumer was within reach of a Sears or Montgomery, Ward catalog. Delivery times almost anywhere in the country were thirty days or less, which prevailed until air-freight deliveries became widespread three-quarters of a century later. In order of magnitude, the gains in distributional efficiency were probably greater than those from the Internet in our own day. And with consumers as the driving force behind growth, the American economy was roaring ahead at a rate faster than any country had ever sustained over so long a period.

Leaving Britain Behind

American industrial output steadily closed the gap with Great Britain throughout the nineteenth century and then exploded to the top rank. In 1800, the output of American factories and mines was only a sixth that of Great Britain; by 1860, it was a third, and by 1880, two-thirds. American industrial production pulled ahead of Great Britain’s sometime in the late 1880s and by the eve of World War I was 2.3 times larger. In 1860, Great Britain accounted for about 20 percent of world industrial output and the United States only about 7 percent; by 1913, the American share was 32 percent, while Great Britain’s had slid to 14 percent.

11Strikingly, despite the country’s high rate of population growth, per capita industrial production grew faster in the United States than anywhere else in the world. Industrial output per head grew sixfold in the United States from 1860 to 1913, compared to only 1.8 times in Great Britain. Only Germany among the major powers showed a per capita growth rate (5.6 times) comparable to that in America, and the Germans started from a much lower baseline. (On the eve of the Great War, decades of hyper-rapid growth had pulled German output to Great Britain’s level.) By the end of the 1870s, America dominated international trade in grain, enjoyed a near monopoly of the world meat trade with a 70–80 percent share, and enjoyed at least as great a share of the burgeoning global petroleum market. As for the other Great Powers, France steadily lost ground to both Great Britain and Germany, while Russia remained a sink of despondency.

Late nineteenth-century British savants were mesmerized by the relentless American advance. A near-obsessive search for the causes of the relative British decline spurred a century’s worth of economic history on both sides of the Atlantic that offers a superb lens for tracing the sources of American advantage. The divergent paths followed by the American and British steel industries were the most intensively researched, because they were among the few that readily lent themselves to direct comparison.

Loss of leadership in steel was especially painful for Britons. Steel was the foundation industry for the late-Victorian period, much as information technology is today. Nor was there any question of British ability to produce the world’s finest steel. Sheffield steel set the quality standard for the world, and its crucible steel had almost the status of a semiprecious metal. Almost all the era’s steelmaking advances came from the United Kingdom: the hot-air blast furnace, the Bessemer process, and the Thomas-Gilchrist basic lining, enabling the use of high-phosphorus ore. Charles Siemens invented the furnace used for the Siemen-Martin open-hearth method of steelmaking that competed with Bessemer’s, especially in nonrail applications. Siemens belonged to the great German industrial family but spent most of his life in England and eventually became a citizen.

The American challenge lay in the vast growth of its steel-making

capacity . Stephen Jeans, secretary of the British Iron Trade Association, and the steel engineer Frank Popplewell both wrote book-length surveys around the turn of the century seeking the reasons for the American success.

12 As Jeans put it, just the increase in the American output over the six years from 1895 was “considerably larger than the total output of steel of all kinds throughout the world in any one year prior to 1890, and is about half a million tons more than the total make of steel in Great Britain in any two years prior to 1897.”

13 Jeans glumly noted that American annual steel and pig-iron output was already twice as large as Great Britain’s and greater than the total of Great Britain and Germany combined.

Popplewell and Jeans each make it clear that the American advantage involved no fundamental breakthroughs but was rather about methodologies, work organization, and mechanization. Popplewell’s list of the characteristic features of an American plant were all in place at Carnegie’s Edgar Thomson Works by the early 1880s. There were some splendid British steel plants; indeed, Holley had extolled several as models for the United States. But there were many more older, smaller plants and a lower degree of mechanization. Continuous processing through the entire ore-to-steel cycle was rare, and smaller plants could not afford expensive equipment like the chargers that injected the chemical and mineral additives into the converter mechanically. Popplewell commented on the “very conspicuous absence of labourers in the American mills.”

14 American rail and rod mills routinely produced three times the output of British mills with fewer than half the men.

The cost advantage once enjoyed by the British industry from its conveniently located ore and coal supplies gradually disappeared as Americans mechanized ore mining and transport through the 1890s. Great Lakes Mesabi Range ore was surface-mined with giant steam shovels, and Popplewell was awestruck at lake port ore handling: huge mechanical clamshell shovels unloaded 5,000-ton ore boats into moving lines of freight cars, at rates over 1,000 tons per hour. Carnegie Steel’s own Pittsburgh-to-Erie railroad, with some of the largest cars and the most advanced loading facilities, had driven ore transport costs as low as a seventh of a cent per ton.

The big American production runs were facilitated by a high degree of product standardization. Holley had pressed hard to standardize rail patterns before his death in 1882, but it was not accomplished until 1898, compressing some 119 different rail designs down to just 10. Carnegie Steel accomplished a similar result in structural steel at about the same time, with the publication of its structural steel handbook, which was soon adopted by the whole industry. The British found standardization much more difficult, in part because so much of their product was exported and in part, as in the case of rails, because of the resistance of smaller railroads and the manufacturers that serviced them.

The British still led the world in the scale and quality of their ship-plate production and in other high-end products, and no other country, Jeans felt, could match the British in ultralarge steam forges for ship components. Although American locomotives from Baldwin were spreading throughout the world, Jeans did not think they came up to British quality but conceded that they were cheaper.

Jeans’s overall conclusion, that American steel “can compete with Great Britain and Germany in the leading markets of the world,”

15 was sugar coating for his parliamentary audience. The scale, the aggressiveness, the modernity of the American plants that he so painstakingly documents leave little doubt that the contest was over. Indeed, just about the time Jeans completed his review, Great Britain was transmuting from the world’s dominant steel producer into the largest steel importer. Both American and German steel, it seemed, were underselling Great Britain in its home market.

The failure of the British to keep pace is a classic example of the disadvantages accruing to a technological first mover. By the time American and German competitors appeared on the scene, the structure of the British industry already had a settled character. The prevalence of smaller companies, many specializing just in iron or just in steel, was not conducive to American- and German-scale processing efficiencies and mechanization, for they were not cost-effective for any but the largest works.

Just as important, a competitive late entrant usually starts with the most modern plant, and if it enjoys a high growth rate, requiring constant plant additions, its advantage in facilities will steadily grow. Older competitors, with flat or falling shares, will find it commensurately hard to finance plant upgrades. By the 1880s the British industry was clearly behind the Germans and Americans in production technology. A number of Britons understood that only a root-and-branch reconstruction of the industry could restore its competitiveness, but the financial and organizational obstacles, in a country committed to laissez-faire economic principles, made it practically impossible.

A long finger of suspicion points at both British workers and British managers. Most fair-minded observers conceded that American and German workers and bosses were better educated and more open to scientific advances. Worker recalcitrance and union resistance were major obstacles to mechanization throughout British industry. But British managers also played a big role in the deterioration. The entrepreneurial drive of the 1840s and 1850s had markedly ebbed. Old-school managers, consciously or not, connived with their workers to stick with what they knew: the smaller plants, the old methods, the clubman’s version of genteel competition. As one expert put it, “outside England people say, ‘What is the saving?’ In England, the first question is, ‘What is the cost?’” A sympathetic American was struck by the “pessimism and lack of courage” among British iron and steel men.

16The same slippage can be seen in the British chemical industry. In mid-century, Great Britain led the world in inorganic chemicals (ammonia, caustic soda, sulfuric acid) but failed to adjust when the new Solvay technology emerged in the 1870s; within a decade German and Belgian manufacturers had perhaps a 20 percent cost advantage, with far less environmental damage. The Americans came on strongly in the late 1890s, starting with the Solvay process and the even newer electrolytic technology. Similarly, in electrical power generation, the steam turbine engine, one of the critical enabling technologies, was invented by an Englishman, Charles Parsons, in 1884. But the industry was quickly dominated by America’s General Electric and Westinghouse and Germany’s Siemens. Some failures seem cultural. In reaction to a wave of machine-made American shoe imports in the early 1900s, British industry switched to American shoemaking machines yet somehow never realized American productivity levels.

Jack Brown, an industrial historian at the University of Virginia, supplies a striking example of the British cultural difference. British rail lines typically made all their equipment—not just their locomotives and cars, but everything else, including tapestries, table-settings, ticket-blanks, and furniture. That was not absurd: each was seeking to express a specific company personality to its employees and customers. U.S. rail lines, by contrast, outsourced almost everything—George Pullman owned and maintained virtually all the lines’ luxury sleeping cars. The only value being served was economic rationality. When British lines were forced to turn to American suppliers during a long 1895 strike, they were shocked to find that they were saving 30–40 percent on their own costs of production.

17Finally, the vulnerability of the British industry was increased by the country’s ideological commitment to free-trade dogma, in face of steep protective steel tariffs in both the United States and Germany—and on the part of the Germans, flagrant, predatory, below-cost “dumping,” as they attacked Great Britain’s steel markets everywhere. (An important distinction is that US trade policy was protective but not predatory. It artificially obstructed British imports, but almost all of its steel production was consumed at home. Germany’s strategy was predatory: it dumped most of its production overseas, making up the losses by charging high prices at home.)

It is all the more remarkable, therefore, that the British political and business establishment emphatically rejected a return to protectionism in the early 1900s, even though it was labeled, reasonably enough, as “fair trade” retaliation against predators. The politics and interests involved were complicated, but to a striking degree, the rejection was based on a web of highly abstract arguments. As the

Times put it, “Protection . . . brings its own punishment. Nature will retaliate upon France whether we do or not.”

18 The flower of the British economics establishment, the legendary professors Marshall, Pigou, and Jevons, all pronounced on the folly of trade restriction, insisting that the British industry was merely undergoing a “natural” adjustment. Winston Churchill worried how ministries and Parliament, “hitherto chaste because unsolicited,” might behave once the protectionist bawd ran free.

19In the United States, the usual penalty to the protective nation—excessive prices—did not apply in steel because of Carnegie. By economic rationality, if British steel was selling at $25 per ton pretariff, American steel makers would price as close as they could to $53 ($25 + $28). That is why tariffs were often called the “mother of all trusts”

20—the windfall profits were so high that American firms would quickly reach market-sharing agreements, as happened in sugar, whiskey, tin plate, and other industries.

But it didn’t happen in steel. From 1886 through 1899, the British export price averaged $23 per ton, or $51 to the customer after the tariff. But the average selling price from American Bessemer mills was only $28. In other words, the Americans left $23 of available tariff protection on the table; in 1897 and 1898, the average American price was actually lower than the British pretariff price. In steel, in other words, the tariff had only minimal impact on final prices, because of Carnegie’s persistent drive to steal share from his competitors.

21The primary driver for J. P. Morgan’s purchase of Carnegie Steel in 1901, and the roll-up of most of the rest of the industry in a new conglomerate, US Steel, was to reestablish the cartel. With Carnegie safely dispatched to the fields of philanthropy, Morgan could finally slow the march of technology to staunch the drain of capital spending, and keep steel prices at whatever level was needed to service his massive acquisition debt. From then on, most new advances came out of railroad or automobile company labs, or from overseas. US Steel settled into the sleepy dominance that came to characterize nearly all big American industries until the Japanese and German assaults of the 1970s and 1980s.

While England Slept

By the end of the century, the United States, almost inadvertently, was poised to make inroads into Great Britain’s dominant position in global finance. The British branch of the great Rothschild banks was run by “Natty” Rothschild, grandson of old Nathan. The London house’s founder was accustomed to be lead finance house to underwrite British overseas adventures. When the South African war broke out in 1899, Rothschild was shocked to learn that the government planned to grant half the financing mandate to an American syndicate led by Morgan. After fierce lobbying by the financial elite, Morgan was given only a very minor role during the first round of fund raising. But as drawn-out war pressured British gold reserves, the Exchequer had no choice but to give Morgan an equal role. Worse, it was forced to yield to Morgan’s peremptory demand that he get twice the commission as the British consortium. Niall Ferguson, the historian of the Rothschild family, writes, “It was an early sign of that shift in the centre of financial gravity across the Atlantic that would be such a decisive—and for the Rothschilds fateful—feature of the new century.”

22The underlying tidal shift was that the United States was transmuting from a debtor to a creditor nation. America’s long history as a debtor was the inevitable result of its persistent trade deficits on top of the strong inflow of investment capital, primarily from the British.

The trade deficit began to shrink in the latter part of the 1870s, primarily from a big jump in exports of grain, flour, meat, and animal fats. Purely in merchandise trade—that is, excluding services like finance and transportation—the United States was nearly always in surplus after 1876 and finally flipped into surplus in both goods and services in the mid-1890s. By the end of the century, its finished manufactured exports had a dollar value greater than either cotton or wheat.

23A country’s international credit/debtor position is the difference between all American claims on the rest of the world and vice versa. Foreign claims on America include not only outright borrowings, but any foreign ownership of stock, land, or any other American asset. The United States was a net debtor nation through the entire nineteenth century, primarily because of foreign investment flows, as in the late 1830s, 1850s, and post-Civil War booms in railroads, cattle ranches, and other real assets. America first became a net overseas investor in the late 1890s, mostly in Canada and Latin America. The huge surpluses earned during WWI made the United States by far the world’s largest creditor nation.

24And now, as everyone knows, America is itself in danger of being pushed off the top-dog pedestal. In the next chapter we will look briefly at the looming contest for economic dominance between China and the United States, and its similarities and differences compared with the one between Great Britain and America a century and a half ago.