W. A. Swanberg

He was a sparse-haired, pale, timber-wolf kind of man, quick in his movements, and very decisive in his speech, as frequently happens with men who are afraid they might fall into a stammer. He had shaggy reddish eyebrows and cold, pale-gray eyes [pale blue, really] that hardly ever participated in his rare smiles.

I felt at once that there was a great deal of dangerous integrity in the man. I mean, the sort of integrity I generally associate with the head of the Women's Christian Temperance Union. An almost unbribable pig-headedness. It was also instantly obvious that he didn't have a shred of humor to cover any part of his almost frenzied intensity.

Hired, King gave a dozen cheap cameras to chimpanzees in a zoo, with which a few of them accidentally took pictures of spectators looking at them through the bars. These were published under the title, "This is what you look like to the monkey in the zoo." Among his many other ideas was a life-size picture of a twenty-one-inch dwarf who just fitted into Life's double-page twenty-two-inch dimension. But he disliked the kind of sanctimonious commercialism he found in the "Ivy League clothes dummies" running the Lucepress. "Nearly everybody was scared stiff of his job," he wrote. He disapproved of Time's eternal propaganda and its tricks such as its habit of following the name of Leon Trotsky with the parenthetical "(ne Bronstein)":

... It seemed to me that the editors of Time liked to . . . expose him as just a cheap little Jew who, in the manner of his breed, had, for devious, shady reasons, decided to change his monicker.

He commented on the central evangelical theme:

Everybody in his right mind knows that Communism is a hell of a way of life. ... So?

So I'd like to make it plain at once that that still doesn't make unhampered, catch-as-catch-can capitalism into a snow-white maiden. . . . Life, Time and Fortune ... do unremittingly sponsor the notion that to lack faith in capitaHsm is tantamount to spitting at the holy source of divine wisdom itself, because man can never hope to aspire to any nobler spiritual plateau than the expectation of six per cent interest on invested capital.

An unfailing party-enlivener, King was a guest of the Luces at Greenwich and at Mepkin, but he tired of his job and quit after only three years. There was general relief, for he was not the type the company liked to encourage. He did not have the faith.

1. THE MEEK PEOPLE

In 1938 Europe came to such a boil that Luce had to examine it even though his own affairs were cooking in New York. In May, Time absorbed the 250,000 remaining subscriptions of the Literary Digest, which in fifteen years it had beaten into submission. That same month, Time Inc. moved from its six-year home in the Chr)'sler Building to the top seven floors of the brand-new thirty-six-story Time-Life Building on 49th Street, a part of the massive Rockefeller Center complex. Billings, on vacation in South Carolina, had been implored to hurry back to Life so that Luce could leave. "Luce took me up to see his office on the roof," he told his diary, "—a magnificent double-story affair fit for old Duce or Luce." It would become known as the Penthouse. Luce took BiUings to lunch at the expensive Louis XIV restaurant across the street and sailed with his wife that afternoon on the splendid Queen Mary —which could be seen at its pier from the Time-Life offices. Only six weeks earlier the Nazis had marched into Austria, consummating the Anschluss which caused the Rome-Berfin Axis to reach unbroken from Baltic to Mediterranean. Luce had recently given a speech predicting world war in which America would be involved, but he did not really beheve this. It had been given to an all-Yale group at Montclair, New Jersey, men whose complacency he felt constrained to disturb, saying:

. . . [W]e Americans are entirely too cheerful. ... In my time, Yale was turned into a military training camp. I think the chances are at least fifty-fifty that Yale will again be turned into a military training camp within ten years. . . . [R]ight now the gentlemen of England are trying to make up their minds whether they will let Germany grab Austria and Czechoslovakia. . . . War in Europe, war in Asia—and we stay out?

153

W. A. Swanberg

And he returned to his theme—indeed his obsession—of Ortega y Gasset, warning that the mass mind was a threat not only in Europe but in America where, he felt, pobtical ideals had withered under the New Deal:

One of the most brilliant works of our time is certainly Ortega y Gasset's thesis on the triumph of the mass-mind. The mass-mind shows itselF in dictatorships. The mass-mind shows itself also in unrestrained and rudderless democracies.

Elaborate plans had been made by the Time organization for him to meet important and knowledgeable people abroad—always his goal no matter where he was. If he resembled a drama lover from Grand Rapids visiting New York to see ten plays in ten nights, it was the only way it could be done. His curiosity and his passion for first-hand observation were unmatched by any of his peers. The European trips of Adolph Ochs, Roy Howard, Hearst and Colonel Robert McCormick were vacation jaunts by comparison.

In London the Luces visited Ambassador Joseph Patrick Kennedy, whose hospitality could hardly have been impaired by the flattering cover story Time gave him when he was Securities and Exchange Commissioner ("an ideal pohceman for the securities business"). Kennedy, perhaps not without White House ambitions and thoughts of Lucepress friendship, arranged an invitation for the Luces to a ball given by the Duchess of Sutherland, where they met the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, in whom Luce had a joumahstic as well as a social interest. He conferred with Brendan Bracken, Harold Nicolson, Lord Beaverbrook and others. Cassandra, the London Daily News columnist, in noting Luce's visit, recognized both his pohtical power and literary sins:

They talk of him as a future Presidential candidate. Our elder statesmen and Potent Peers of the Realm curried his company. He was feted, dined, wined, complimented and plastered with praise. . . . Mr. Luce presents the news [in Time] in a way which he describes as being "curt, clear, complete." . . . And that style is as vile a piece of mangling as has ever stripped the heart out of prose.

The London Bystander also mentioned him as a Presidential possibility, adding, "Henry Luce is also a chain-smoker, heart-breakingly punctual, exceedingly idle about his clothes, and unable to forget, when dealing with waiters, that way back in China his father . . . had half-a-dozen 'boys' at his beck and call."

Going on by air to Berhn, the Luces were the guests of a wealthy German businessman at a gathering attended also by an American businessman from Stamford, Connecticut. After dinner. Luce brought up the subject of National Socialism. As he described it in the 6000-word report he made of his trip:

Herr [his host] is not even yet a member of the party, but he is a tremendous enthusiast for Germany if not for National Socialism and it was with an al-

Luce and His Empire

most pathetic eagerness that he besought [the American from Stamford] to take the floor and explain to us outsiders the merits of Hitler's Germany. This Mr. [ ] was glad to do. . . . He said that if he could take a year off to do nothing except study the ways and destiny of man in the twentieth century, the place he would come to, of all the countries in the world, is Germany. Whether or not you like it, Germany is the place where you are most Ukely to learn most about what you are going to get in the U.S. and elsewhere in the world, he says. . . . The great and first impression I got ... is that National Socialism is a socialism which works mightily for the masses however distasteful it may be to them personally in many ways.

This patronizing of "the masses" was perhaps unconscious: ". . . in Germany there is no 'soak-the-rich' ideology," he wrote. ". . . The extraordinary thing about Hitler, at least for the moment, is that he has suspended the class war . . ."

The Luces had tea with the Hitler-truckling British ambassador in Berlin, Sir Nevile Henderson. They were driven south in a Cadillac by a relative of their Berlin host and lunched at Bayreuth:

. . . [I]t was there I first saw the paper edited by Streicher and entirely devoted to attacking Jews . . . there has been no exaggeration as to the important role which anti-Semitism has played in the Third Reich or as to the intensity of this brand of hatred. Our friend [the driver] . . . was anything but a "natural" Nazi, but even he accepted anti-Semitism as, at least, a necessary evil in the rebuilding of Germany under the Third Reich.

He listed points, some on the credit side, some on the debit, of this German brand of dictatorship. Fifteen busy theaters in Munich caused him to report, "Any idea that the Nazis have put the kibosh on culture is ridiculous." He thought the Nazis and the New Deal alike in their use of vast sums of money for self-advertising building programs. Luce in several speeches had made sarcastic mention of demagogic New Deal gestures toward "the people" in America. To him, the term seemed to mean a combination of the politically exploited and the lumpen that he, along with Ortega y Gasset, feared. He made repeated ironical use of it in mentioning the popularity of the motorbike in Germany:

. . . [T]he German people are on wheels by the millions—the People. Yes, the People. Oh, make no mistake, the People, the meek People who have inherited the earth. We read of Germany as if it were the private domain of Hitler with just enough people to serve him for an audience occasionally, and with an Army to parade around and amuse him. But the visual impression of Germany is of a People's land. I never saw Hitler. I saw many soldiers casually here and there but I saw no Army. I saw only The People and The People and The People. I do not know what they are but they did not seem to be slaves. Their chains are not visible.

They took the route Hitler had used in the Anschluss, attended the opera

W. A. Swanberg

in Vienna and dined with the American consul general, a man named Wiley: "Wiley is married to a charming Polish Jew and is 100% anti-Nazi but he too, I think, agrees that National Socialism is thoroughly misunderstood in the U.S."

At this very time the Nazis were increasing their pressure on the Czech Su-detenland. In Prague, Luce talked with President Eduard Benes (whom he had last seen in 1921 while on tour from Oxford) and was affected when Benes swore the Czechs would defend their land, saying, "Ask anybody— anybody you meet in the streets-—and he will tell you he will fight." Luce observed, "We saw tens of thousands of good stolid Bohemians going about their business . . . men— and women—who would fight and die for country and for liberty. It was a thrill—I confess it—to touch, however briefly—such a people." He added, "... I know no such men of courage in America. We in America have totally forgotten what it is like to . . . [be] with men who will fight . . ." But this was Luce the mihtant, the admirer of courage as a virtue in itself, not Luce the internationalist making any decision of his own as to the merits of the Sudeten question. He made none. "The first German plane which arrives over Prague is, I am sure, a dead plane," he wrote. But after he had gone on to Karlsbad, talked with the Sudeten German leader there and heard his story about the "subjection" by the Czechs of the Germans within their boundaries, he seemed to swing toward the Germans:

It may well be true that there was no "Sudeten question" until Hitler came along. But on the other hand the real moral of all this is that Europe is not divided into countries but into vaUeys, and every valley has its history and its local demons and its fairies. . . . Without this deep emotional attachment to place, you cannot have civilization, and yet, of course, this very attachment to place breeds conflicts between places. We must not be contemptuous of Europe because it has this Spirit-of-Place, this attachment to soil—what Hitler calls Brot and Boten [sic]. We need much more of it in America . . . We must recognize that this is necessary to civilization . . .

In Paris the Luces were the dinner guests of the American ambassador, that odd number, WilUam C. Bullitt, now congenial to them since his former infatuation with the Soviet had swung to the opposite extreme. Charming and an intriguer, BuUitt, if later rumor could be believed, was then pulling strings for a European accord against Stahn that would take strange shape at Munich. His guests, in addition to Cabinet ministers, included Andre Maurois, Louis Bromfield and M. Bailby, owner of Le Jour, the Paris paper that was said to have received huge secret payments from Mussolini for supporting a French pro-Fascist policy. The air was charged with machinations, into which it is not impossible that Luce may have been initiated by Bullitt, a man who knew the power of the press. Luce wrote, "To the vast glee of Bullitt and Novehst Bromfield and others assembled, I asked M. Bailby to explain to me the morals of the French press and whether its reputation for corruption was jus-

Luce and His Empire

tified." He commented favorably on Pierre Laval and felt that Fortune had been too kind to Leon Blum and the Popular Front—feelings certainly shared by BuUitt:

. . . Communism is a much bigger thing in Europe than it is in America. There were iiiillions of actual official Communist votes in Germany before Hitler. In France there is a very large block of actual Communist votes seating 72 Communist Congressmen and there are whole suburbs around Paris which are Communistic—not merely in the alarmist American sense of the word, but as an actual party organization.

Although he announced no specific conclusions, the tone of Luce's comments suggested agreement with Bullitt that Europe might be approaching a Fascist-Communist showdown in which American interests lay with the Fascists, and a strange air of coolness over the prospect. The Hitler career of international blackmail was on the record, and although Nazi indecencies against humanity were not yet perpetrated daily on fashionable streets in broad daylight, they were known to the world. Luce seemed to walk through this evil without a twitch. He listened placidly to the wealthy Berlin businessman-apologist and the wealthy American businessman-apologist for Hitler, and became in his report a near-apologist himself, suggesting that Nazism was "misunderstood" in America and that better comprehension would place the Nazis in a better light.

2. THE FOUR CHEEKS AT MUNICH

The Luces arrived in New York on the Queen Mary June 20, having had Ambassador Kennedy as a companion. Luce took Clare home and hurried to the office as inevitably as a racing addict would have gone to the track. "He sat on my picture table swinging his legs," Billings wrote, "and talking about the bigwigs he'd met. Joe Kennedy, Edward of Windsor—he'll probably entertain the Windsors when they come to the U.S."

Clare's new play Kiss the Boys Goodbye, a social satire which she was said to have written in a month, opened in New York September 28. Time's drama critic was now the solid Louis Kronenberger, who remarked that he could Kiss the Boss Goodbye if he did not like the Boss's wife's new play. But his review was bravely lukewarm, daring to say that by comparison with the leading character, some others were "dramatically flat." It got by the Boss without change and he never seemed to hold it against Kronenberger. But he did make handsome amends to his spouse when her play received rousing praise in the following week's Life, which called it "high comedy" and saluted her for smashing the jinx that usually follows a hit by producing another hit. Life's four pages and twenty-four pictures with glowing captions made priceless publicity, the envy of other playwrights less favorably connected.

W. A. Swanherg

When Kronenberger later was a guest at Luce parties, he observed, Clare "tended to shake my hand while scanning some far horizon, and to murmur goodbye as though seeing the last of a rather incompetent footman. Once, however, she did remark with a strong hissing sound, 'I'm ssssso glad that we sssso often sssee eye-to-eye about the theatre.' "

On September 30, Luce's prediction that the Czechs would fight was undercut by the turning of "all four cheeks" by Chamberlain and the signing of the four-power Munich pact from which Czechoslovakia, as well as Russia and the League, was excluded. Chamberlain and Daladier, in placating Hitler by awarding him most of the Sudetenland and later informing the Czechs that they must submit, were delaying World War II only by a scant year and for a heavy price—Czech border fortifications that would have stopped the Nazis in a two-front war, plus thirty-five Czech divisions.

Time praised the pact, saying it was easy for those not threatened to criticize: "Really scathing attacks on Neville Chamberlain were made almost entirely from extremely safe distances of several thousand miles . . ."It followed a sly Time propaganda custom by attributing criticism of Munich to people it downgraded, notably "certain Manhattan news broadcasters" of whom it named only "Johannes Steel, a German agent on mysterious missions in Brazil until the Nazis came into power." The following week Chamberlain was Time's honored cover subject. It noted that "energetic, square-jawed" Premier Daladier got a 535-75 Chamber vote of confidence on the Munich question, "nearly all the dissenters being Communists." In the Commons, Winston Churchill drew scowls when he warned, "We have sustained a total, unmitigated defeat . . ."

Time's foreign news had now grown obnoxious to many middle-roaders. Kronenberger remarked on Goldsborough's "pro-fascist, reputedly anti-Semitic " hne and how his "week-after-week treatment of the European situation was getting to be as inevitable a topic as Goldsborough's presence in the office was becoming an embarrassment." At the time of Munich, Luce seemed in substantial agreement with his FN chief. He still did not believe war was coming, his journalistic-missionary efforts were devoted to isolating the Russians, and the Axis still seemed a God-given weapon aimed straight at Bolshevism. But within his organization the group protesting this view grew more restive, among them Ralph Ingersoll. As general manager of Time, In-gersoll was also embarrassed by a sag in circulation he blamed in part on Goldsborough. A few weeks after Munich he wrote Luce:

If ever the returns were in on the failure of a major department, the returns are in on Time's Foreign News. . . . Goldsborough has almost consistently been sly, unfair and uninformed. But in the face of the greater charge of being unfeeUng, this is almost beside the point. People do not buy hundreds of thousands of copies of the writings of a tired, tired Jesuit. . . . My prescription is that he be given a year's leave of absence. . . . Goldy's gossipy mind was amusing in the

Luce and His Empire

20's, it is not amusing now . . . And utterly inconsistent with that basic premise of Prospectus No. 1, "We believe in the existence of Good and Evil."

This criticism of Goldsborough was also to some extent criticism of Luce himself, who was beginning to fmne at Ingersoll's tough officiousness. But he knew that even conservatives such as Mrs. Helen Reid of the Herald Tribime were taken aback by Time's irresponsibility in foreign news. Ingersoll's mention of "Good and Evil," of course referred to Time's original prospectus, so carefully drawn by Luce and Hadden. Goldsborough was raising a problem of morale on the staff, and circulation figures were holy symbols. Luce's final agreement with IngersoU about the FN editor was on the ground of style rather than of judicious treatment of the news.

In November Luce took over the editing of Time for a week, in so doing reading Goldy's copy hot from the pencil. On December 8 he sent a memo "To all Time Writers and Editors" giving Goldsborough generous praise after its opening paragraph: "With the best wishes of all of us, and no doubt a little of our best envy. Laird Goldsborough begins this week his long-overdue sabbatical year." Robert Neville and other younger men thereafter wrote FN. At the same time Luce made another gesture toward his rule of "handing the company over" to younger men by retiring Myron Weiss, who had reached the advanced age of forty-four. Weiss recalls that Luce was very kind, "hated to do it" and paid a handsome severance sum.

The Luces went to Mepkin for the hohdays with the two Luce boys, Ann Brokaw and a number of guests including the Allen Grovers and the Daniel Longwells, Mrs. Longwell being the former Mary Eraser, one of the few women to attain editorial status at Time. The main house was still unfinished but five guest houses designed by Stone had risen, each air-conditioned, indirectly hghted and having glass walls facing the river. Neighbors were critical of such functional glitter in a country of pillared verandas and moss-dripping liveoaks. "Why should I build an old mansion on the Cooper River?" Clare asked with some justice. "I have no roots there. This is none of my tradition, and it would be false to ape the old ways."

The common enjoyment she and her husband took in addressing an audience occasionally brought darkness to the Lucean brow, since she could interpolate entertaining remarks on her subject while he was articulating his own. Sometimes, at the long dinner table, the Luces seemed to compete for their guests' attention, Luce seizing listeners at his end while Clare gathered those at the other. The serious Luce at times seemed unaware that she could say extravagant things simply for effect which less literal listeners were expected to discount, and in any case he hewed to the husband-is-master doctrine. On one occasion when they disagreed about something, it was said, Luce leaned forward and asked icily, "You are sure that you are right, aren't you? Absolutely sure?" "Yes," Clare replied, "I am absolutely sure." "Well then, if you are that sure . . . then are you wiUing to bet one million dollars?" Although the

W. A. Swanberg

angry Mrs. Luce did not accept the challenge, it seemed entirely serious and some of the astonished guests realized it was not beyond the couple's resources. The Mepkin duck shooting, too, could create strain, for she was the better marksman and he loathed being beaten at anything by anybody.

Luce posed for Jo Davidson, who was making a bust of him. Meanwhile, in the Time-Life Building, Ingersoll was making a momentous decision. Time's Man of the Year—a selection Luce took with great seriousness—had already been chosen. Newsworthiness rather than righteousness being the criterion, he was of course Hitler. Time had an excellent color picture of him in uniform which, however, did not show his fanaticism and made him appear rather like a banker in khaki.

"I did not see how Time could put this dignified picture of him on the cover without conveying some kind of tacit endorsement," Ingersoll later explained, without adding that Time's dignified textual treatment of him had often given a similar impression.

After much agency search he found a lithograph by an Austrian who had fled the Nazi terror, Rudolph C. von Ripper. It showed a small, diabolical Hitler playing a huge organ which actuated a monstrous wheel from which hung the bodies of his victims. It became the Time cover for January 2, 1939, with the caption: "Man of 1938: From the unholy organist, a hymn of hate." With it was a text piece abandoning the attitudes of the three-weeks'-de-parted Goldsborough, a few passages reading:

. . . Herr Hitler reaped on that day at Munich the harvest of an audacious, defiant, ruthless foreign policy he had pursued for five and a half years. . . . Hitler became in 1938 the greatest threatening force that the democratic, freedom-loving world faces today. . . . Small, neighboring States . . . feared to ofi^end him. . . . The Fascintem, with Hitler in the driver's seat, with Mussolini, Franco and the Japanese military cabal riding behind, emerged in 1938 as an international revolutionary movement. . . . The Fascist battle against freedom is often carried forward under the false slogan of "Down with Communism!" . . . Civil rights and liberties have disappeared. Opposition to the Nazi regime has become tantamount to suicide or worse. . . . Germany's 700,000 Jews have been tortured physically, robbed of homes and properties . . . Now they are being held for "ransom," a gangster trick through the ages. . . . Out of Germany has come a steady, ever-sweUing stream of refugees, Jews and Gentiles, Catholics as well as Protestants, who could stand Nazism no longer. . . .

Had not Time for so long applauded the Fascist dictators, these things would not so badly have needed saying. Luce himself had approved the text after criticizing it for being too anti-Fascist and adding a paragraph listing Hitler's achievements within the Reich, but it seems possible that such sentiments as "The Fascist battle against freedom is often carried forward under the false slogan of 'Down with Communism!' " may have been shpped in during his absence. A breakthrough of near-honesty had been made. It must have puzzled the more pliant readers who had for so long been led by this same

Luce and His Empire

magazine to think well of the dictators. As for Time's own liberals, it was said that a large group of them paraded across 48th Street to the Three G's, a favorite saloon, and hung one on.

3. THE GENTLEMAN FROM INDIANA

Ingersoll was a radical who at times spoke obliquely. In a later explanation of the crisis he described himself as a journalist with a social conscience whereas (and here his tongue seems to have been far in cheek), "Harry . . . believed that a journalist should be amoral—with no responsibility except to be accurate [sic] and able to hold the attention of his audience." Ingersoll, already planning to start a newspaper of his own, no longer looked on Luce as his lifelong employer. When Luce returned, to gaze at the Man of the Year issue with distended eyes, Ingersoll described the subsequent interview:

It was in Harry's room on top of the Time-Life Building, and we were quite alone . . . Harry became visibly emotional, flushing and getting that cold set look he gets when he is very angry. We sat looking at each other for about a minute and then he said simply, "Spilt milk; let's not discuss it."

Luce's official objection was that the cover should not be a deliberate instrument of propaganda. Apparently he forgot his deliberately propagandist cover of June 9, 1930—the portrait of Stalin surrounded by Red conspirators. At the same time he took another blow from the left in the appearance of High Time, published by the "Communist Party Members at Time Inc.," which was secretly distributed around the office and instantly became the talk of New York. Among its many complaints it listed fourteen recent firings and blamed Luce:

Psychologically, Time Inc. is a one man organization . . . [A]ll his [Luce's] sub-executives are terrified of him, and this terror seeps down through the whole organization. Mr. Luce is fond of ripping apart an entire magazine on the deadline and making it over again. On occasion he does the same to his stafl^.

"Join the Communist Party! " High Time urged as a way to fight for job security. Its longest feature was headed, "Goldie—The End of Time's Minister of Propaganda," an attack on the distortions of the sabbaticalized FN head. As the New Republic saw it, the article "offers a convincing explanation of Time's curious editorial interpretations of what has been happening in Soviet Russia, in Spain, in Germany, in Italy and in France." High Time also dispensed gossip about upper-echelon personnel. Luce, who would as soon open a brothel as harbor a nest of Reds, was in a passion. Billings wrote in his diary:

At 5:15 an emergency meeting in Luce's office . . . Gottfried, Davenport, Jackson, Prentice, Paine, Hodgins and Bruce Bromley [a lawyer with Maurice T. Moore's firm] . . . Luce proposed that we try to find out who in our company

W. A. Swanberg

was responsible for High Time and fire them out of hand. This precipitated a hot debate. Gottfried, Davenport and Paine warned vigorously against a purge, a manhunt which would get the company bad publicity. . . . The meeting was strongly against Luce's proposal of a frontal attack. . . .

Now Walter Winchell gossiped that Luce had hired detectives to hunt down the Communists of High Time. The New Republic chuckled, "Our detectives tell us that Mr. Luce is going to be very embarrassed when he discovers that those contributors out on the firing line include some people 'way up' on his own staff." Luce, after some thought, sent out an admonitory office memo:

Most of you have seen the sheet "High Time" put out by the "Communist Party Members at Time Inc." I think that just as a gossip sheet it's a pretty amusing job of writing. I also think that the authors of it were disloyal to the organization and to all their feUow workers. ... A publication by "The Communist Party at Time Inc." is just as offensive as one would be by a "Nazi Bund in Time Inc." ... It has been a cardinal principle with us that editors, writers and researchers have a right to spout to one another their views . . . We have had people of all shades of political thought on our staff and I maintain the right of every one of them to speak to every other member of the staff with as much intellectual freedom—and carefreeness—as he would in his own family. . . . Free speech in confidence is essential to group journalism. It would be intolerable if our editors had to feel that they could not open their mouths without having some half-uttered thought plucked out and used to stab them pubhcly in the back. . . .

I think you will agree with me that one of the things not to do is to start a Red hunt. . . .

We cannot get along on any basis except that of free expression toward one another in private and assurance that such confidence wlU not be violated. If anyone feels that he cannot make that confidence mutual on his part, he ought to resign. Certainly ff the management discovers any employee making public gossip of matters that are properly confidential between members of the staff, he will be fired.

—Henry R. Luce.

Time's clandestine Communists came back at him in their second issue, saying, "He called it 'gossip.' WTien you want to suppress free speech, it sounds better to call it 'gossip.' " There was an attack on the use of Life in 1938 as a "Repubhcan Party organ," and on John Martin for steady denigration of the New Deal in Time's NA department: "He does his work by innuendo, by tricky leads, by making New Dealers sinister or foolish and anti-New Dealers dignified and cool-headed." As for Luce, High Time said he had had pohtical ambitions since 1932, had no chance imtil Life became so powerful, and now seemed to have settled for the role of king-maker rather than king. Perhaps most embarrassing was the charge that Time had suppressed news that would antagonize large advertisers—that it had treated the Akron strikes in a manner hostile to labor and favorable to the tire manufacturers.

Luce and His Empire

Troubled over his own "revolt of the masses," Luce wrote an interminable memo which he never sent out, much of it in rebuttal of the theories of Inger-soU. Just who was Time aimed at? Ingersoll had argued that each department should be handled with enough depth to please experts. Not at all, said Luce. Time was meant to be read cover-to-cover by all readers, not patchily by specialists:

And that means that if you are going to ask one man to read Time from cover-to-cover, you have got to work like hell to edit Time for one man. . . . Now, theoretically, the lower the mental content, the wider your audience will be. But that is only theoretically or generally speaking—it is not true in specific cases. The mental content of Life always was about 1000% higher than any other picture magazine and is 2000% higher today—and look at the comparative results. But if you are going to hold 700,000 circulation [on Time], must you edit for the last and dumbest of the 700,000? No—or if that is so, the Board of Directors of Time Inc. will flatly authorize you not to edit for same. Time is going to be a damned intelligent paper—let the circulation chips fall where they may. . . .

Time is edited for the Gentleman of Indiana and for Madame the Lady of Indiana. . . . Time is going to write for the Gentleman of Indiana, writing to him as man to man, in straightforward decent language, no punches pulled, but no dirty below-the-belt cracks either at God, the Constitution or his fellow gentlemen of Indiana. . . .

That meant perpetuation of the meat grinder, the writing of every story to maintain editorial "unity" and satisfy cover-to-cover readers with all text at a similar level of understanding. The editor-in-chief also loosed a bolt at Ingersoll:

Someone else around here, call him Mr. "X," is worrying about Time's intellectual or interpretative level. Well, now, what I would like to do is to change places with Mr. "X." Dear Mr. "X," if you will guarantee that Time's newsstand circulation will move steadily forward, I will gladly be responsible for Time's intellectual level. ... I fancy I could be a pretty hot intellectual myself if I ever had the chance to be. I, too, could probe the European situation to its very gizzard. ... So, Mr. "X," . . . I'll take on the job of being [Time's] intellectual mentor and elevator. . . .

I do not conceive of myself as having to be the continual Moral Schoolmaster of this place. But I think I cannot escape being the custodian or depository of "Time's conscience." Possibly therefore an informal, unwritten custom should be established—namely that any senior editor or senior executive of any Time Inc. publication who is troubled about any tendency involving editorial conscience should understand that he can and should come to me about it at any time. Practically, and recognizing that we are all frail mortals, it is a question of mutual confidence and respect. If fundamentally any senior does not have sufficient confidence and respect for my ethical attitudes, he should, I think, put me on notice to that effect . . .

W. A. Sivanberg

In April 1939, Ingersoll, who had questioned Luce's ethical attitudes, left Time to start work on the liberal-leftist newspaper PM, where he would prove himself as obdurate in his prejudices as Luce was in his.

4. THE REPUBLIC IN DANGER

Other changes at Time enunciated the banishment of Ingersoll and the renewed hegemony of the Boss. Under Gottfried as managing editor were two associates, Frank Norris and T. S. Matthews. Luce made it plain that he was not only his own publisher but also the top editor, responsible for "general character, tone, direction, ambition and ideals."

None of his three headmen had newspaper experience. Matthews was as close to being politically obtuse as such an otherwise cultivated man could be. A literary perfectionist, he had done much to rid the "culture" departments of the Timestyle excesses which the New Yorker had lampooned. According to Winthrop Sargeant, who had worked under him, Matthews had been "empire building"—that is, aiming for more power and gathering a group of loyal followers with whom he could move in when opportunity came, as it had now. Like most of his colleagues he was nominally a liberal. Astonishingly, despite his ten years at Time, his sympathy for the Spanish Loyahsts, his acquaintance with Goldsborough and presumably with his work, he was unaware of the extent to which Time was a propaganda magazine. He had an intermittent sense of journalistic responsibility. In his new eminence he decided that he must get better acquainted with Luce. As he put it:

I could no longer say that I didn't take Time seriously. I now thought it a barbarous magazine that might, at least in part, be civilized. It had possibilities that hadn't been apparent to me before. I liked my job and wanted to go on with it. But not under any and all circumstances, not under any kind of management."

He invited Luce to dine with him and four colleagues, Norris, Charles Christian Wertenbaker, John Osborne and Robert Fitzgerald. Luce accepted but insisted that the five instead be his guests at his new apartment in the Waldorf Towers on Park Avenue, just two blocks east of Rockefeller Center.

The Luce apartment had the coldness of the habitation of a rich couple pursuing power. Luce, who never knew what he was eating, was hardly more conscious of his surroundings. A couple of the callers had never seen him, much less spoken to him. The dinner gave them an opportunity to see what he was like, and also provided Matthews with two unscheduled meetings with Mrs. Luce. Hunting for a bathroom as the evening wore on, he walked down a corridor, opened a door and discovered Clare before her mirror, preparing

" Quoted from Name and Address, by T. S. Matthews (Simon & Schuster, N.Y. 1960).

Luce and His Empire

for bed. Closing the door and retreating, he turned a corner, spied another door, opened it and now was eying Clare from the other side.

"Young man!" she said severely.

But the unexpected view of Clare was less important than a clear view of Luce's aims. "Luce," Matthews recalled, "could hold the floor and hold it." He was ingratiating and convincing in his exposition of his news policies. It grew so late that the conference was continued a week later at the Luce apartment, then again at the Players Club, where Matthews engaged a private room. As he described it:

When Luce arrived for this meeting he handed us each a copy of a memo he had written. As we read it, we saw that he had anticipated all these final questions and had written his answers. Furthermore he had lifted the argument to a general discussion of journalism, its purposes and possibihties, and ended with a statement of his own journalistic faith. He had cut the ground out from under us. We looked at each other and shook our heads. There was nothing left to say.

Few other press lords would have submitted to questioning by five subordinates, a couple of them far enough down the ladder so that he had never met them. Luce more than once had sent word to Miss Thrasher that he was too busy to see his father, waiting outside. Yet he had given these five a total of ten or twelve hours divided among three evenings. He had gone over the ground so thoroughly in his own mind and was so sure of his ground that he dispersed the doubts of five keen men who had good reason for doubts so soon after Munich and the Goldy crisis. The "soul meetings" with Luce would become a company legend and would form the theme of a novel years later by Wertenbaker.

Matthews's account of the talks names the cast, sets the scene, then leaves out much of the action and dialog. He did, however, name one of the questions he asked Luce. It was in fact the crucial one—the right question in the wrong tense: "Under what circumstances would you consider using Time as a political instrument?" And he gave Luce's answer to that one question:

"If I thought the RepubUc was in danger."

No one seems to have asked, "Is it in danger?" Indeed Luce performed a forensic feat in winning over the five editors who were, to one degree or another, not sure that they wholly approved of his conduct of the magazine. He coiild scarcely have done so had he not been morally certain of his own ground, backed by the angels of the Lord. The greatest question that had arisen among the five was the same one that had troubled MacLeish and a few others—the question of bias in the presentation of the news. He had disposed of that masterfully in his conversation and in his memo to them, disavowing any intention to make Time objective and asserting that objectivity was impossible even if desirable:

Even within our company there is occasionally some confusion on this score. For example, there is a persistent urge to say that Time is "unbiased," and to

W. A. Swanberg

claim for it complete "objectivity." That, of course, is nonsense. The original owners-editors-promoters of Time made no such fantastic claim. . . . You will find an acknowledgment of bias in the first circular. . . .

They were bowled over not only by his skill in debate but by the force of his convictions. They believed in him. They believed in him enough so that they did not put questions that would have occurred to really hard-bitten doubters under aggressive leadership. True, the original circular seventeen years earUer had conceded the impossibihty of "complete neutrality on pubhc questions" and said that Time would exercise the benevolent prejudices common to enhghtened minds such as the belief that the world was round. Only a few thousand people had read it then and had long since forgotten about it. It had been flashed before the readers again on Time's tenth anniversary. Were such warnings supposed to suffice in perpetuity? Would it not be fair to make this point clear in every issue? Should not every reader be informed that he was not reading news but news modified and rewritten to include opinion and suggestion? Did not the subtitle, The Weekly Newsmagazine, assure the reader that he was getting news? Was there not a question of honest labeling of merchandise here? And did not the bias go considerably further than agreement that the world was round? These were logical questions that did not get asked, or, if asked, were turned aside by Luce's impregnable moral assurance.

They were questions that would continue to trouble some of the more thoughtful Timen—questions which in their existence in an unknown number of editorial minds would remain hidden like a skeleton in the closet at Time Inc. for many years, with great excitement arising when someone occasionally was brave enough to open the door.

Aside from Time's skilled adjectival shaping of the news and the people in it, there were at least three levels of communication of its propaganda. There was the relatively rare honest opinion given openly along with an honest news story. There were the opinions cleverly hidden behind the facts of a news story which itself was still essentially true. And there was the twisting of the news itself by exaggeration, selection or suppression. This last could be achieved in many ways—in the case of a pubhc official, for example, by stressing the emptiest or most questionable passages in his speeches and ignoring the constructive and inspiring passages. Time often used this technique on President Roosevelt, not forgetting details fike frequent mention of his use of a cigarette holder, which was regarded as a vote-loser in the virile hinterland. The gimmicks available to shrewd denigrators were hmited only by the fertility of their imaginations. One of them, reflecting Luce's fairly continuous effort to depict Roosevelt as a potential dictator, appeared in Life, where careful search of picture files turned up Hitler, MussoUni, Stafin and the President all in similar poses of shaking hands, pointing, petting animals and pinning medals. The headhne was "Speaking of Dictators," and readers who wrote to complain were assured it was only a joke. Another was Time's cover

Luce and His Empire

story on the American Communist leader Earl Browder whose color photograph, backed by Communist posters, had a clever guilt-by-association line under it: "comrade earl browder / For Stalin, for Roosevelt . . ."

Time's treatment of Roosevelt grew more acid as his second term wore on without real economic recovery and there was some evidence of public disillusionment. It was unequaled in its ability to make a man look incompetent or suspect in the framework of a few compliments that gave an impression of fairness. A cover story on James Roosevelt said the son had grown rich selling "the Roosevelt brand of insurance " to clients whom Time pointedly refrained from suggesting might expect political favors in return. With great good nature Time portrayed the President as a man who liked a drink even better than the next fellow and that "often at banquets the flower vases before his plate conceal as many as four Old-Fashioneds, which he downs before one can say 'J^ck Garner.' "

Although Luce was still susceptible to occasional liberal ideas, his growing hatred of Roosevelt tended to steer him from anything even faintly New Dealish. Time Inc. was full of well-paid liberals in the position of being forced to write propaganda that pained them. Their wrestlings with conscience would be documented in works of fiction as well as fact. In the novel The Big Wheel by the former Time staffer John Brooks, one such writer bemoans his dilemma:

"I know I shouldn't go on writing things I don't believe. I know I ought to quit. . . . And by God I intend to, in another year at the outside. But how can I? I tell you, I need ten thousand a year to keep the apartment! Besides, where could I go from here? This is the top, Dick! The top! This is what men spend their time working up to. The only place you can go from here is down."

1. JACK BENNY AND WINSTON CHURCHILL

When Hitler invaded Czechoslovakia, Time said it was the "signal for a belated Stop Hitler drive," as if its own recognition of the dictator's true stripe had been early. Luce said no more about Nazism being "misunderstood." He urged that America, instead of standing in isolation, summon the world to peace "with all the power and energy we can command." He met with the nation's two most honored public men, reporting on it predictably enough so that Billings wrote in his diary: "Editors' and Publishers' meeting at which Luce reported thus: He had lunch with President Roosevelt privately, and soon after, breakfast with ex-President Hoover, privately. Roosevelt was dull and uninspired and had nothing to say. Hoover was exciting and thoughtful and said plenty. So what!"

Late in June the Luces sailed for Europe, "only for a rest." But at Aix-les-Bains Luce received an irresistible invitation from America's ambassador to Poland, Anthony Biddle, to visit that country, which was then arming against Nazi threats. In view of England's alliance with Poland, he flew with Clare to London to prepare himself with a breathless round of interviews with British leaders. They also attended the London opening of Clare's The Women, which had had trouble passing the censor, and met George Bernard Shaw, whose Socialism Luce abhorred. Shaw, unacquainted with American journalism—or was it a Shavian barb?—later sent Clare a postcard ending infu-riatingly for Luce, "Kindest regards to you and Mr. Boothe." En route to Poland the Luces stopped briefly at the Ritz in Paris, where he wrote his first wife:

Dear Lila: Three days in London of the most strenuous interviewing caused me to miss yesterday's boat with the letter I had intended to write. Flew over here today and in half an hour we are off to Poland.

168

Luce and His Empire

As you know, I had intended to come over this time only for a rest. . . . But in view of the terrific goings on in all parts of Europe, it seemed foolish not to avail myself of various unusual opportunities to look around—and so I'm doing two weeks of joumalisticing. ... I hope to see you before the summer's end.

In Warsaw, where the Luces were among the guests at a ball given by Ambassador Biddle, he was persuaded that Poland would hold off the Nazis because of its "tradition of military patriotism." Hurrying on to Bucharest, where he dined with Foreign Minister Gabriel Gafencu, he became optimistic about the resistance Rumania would offer. "Today there are no braver opponents of Nazi Germany than the governments of the not-so-democratic Republic of Poland and the quite democratic Kingdom of Rumania," he wrote in the 3500-word report he prepared for his editors back home. (Both countries would quickly crumble.) Surely Clare was the instigator of their visit, as they returned through France, with Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas, who recorded it curtly and clearly but incompletely:

. . . We received a visit from Clare Boothe Luce and her husband. They had been to Poland and both were convinced that there would be war. . . . She was embroidering in petit point a map of the United States. She was convinced her husband would become President.

The world reports of Henry Luce, which would ultimately run into the hundreds of thousands of words, were already becoming a tradition in the Time-Life Building. One could never fault his conviction that the way to learn about world crises was to go to the scene and ask those involved. He did, however, expect to arrive at solutions rather quickly. The Luce curiosity still had in it something of the Yale undergraduate pelting his professors with questions. There was in it also something of the pollster, jotting down quick answers and going on to the next individual. In his short report on his activities in London, his comment on his talk with Lord Beaverbrook was, "... my God, what a man, in his huge London Palace-Prison, in his terrifying and fantastically expensive discomfort—Power, Power, Power . . ." Whether the Enghsh took Clare and her petit-point map as an omen of the Presidency, they took Luce seriously as a man of influence and molder of opinion. He was deferred to by "statesmen and potent peers" even more than the year before. England, haunted by the peril of a war for which she was not prepared, needed the American friendship which Luce could influence. His report listed twenty-one persons (not counting Shaw) he had interviewed during his short stay, including Winston Churchill, Lady Astor, Anthony Eden ("infinitely nice"), Viscount WiUingden, Lady Sybil Colefax ("most delightful") and Lord Camrose. He added as if in afterthought:

Oh, of course, the most enjoyable evening of all my pohtical travels! Dinner a quatre with the [Lord Robert] Vansittarts ... in a fashionable restaurant . . . and then we returned to their home for a night-cap, inspected the Vansittart ancestors . . .

W. A. Swanberg

If the Luce reports let the editors back home know he was getting up in the world, they also let them know that he was the most energetic reporter in the establishment and that they had better put similar effort into their work. But his office reputation as a prophet was poor. "Luce came back from Europe at noon," Billings wrote August 14. "He dropped into my office for 20 minutes and talked world affairs . . . He thinks the Poles will fight for their sovereignty. We laughed to ourselves and kissed the Poles goodbye . . ."

His hunch that war would not come in 1939 was also mishandled by events. A week after his return came Stalin's answer to Munich, the Nazi-Soviet pact. To go with this appalling news was a Jack Benny cover, a miUion copies already printed in color for the September 4 Time. "Oh, God," Luce protested, "how I hate the idea of Jack Benny this week." The comedian was scrapped and the man hurriedly substituted was Churchill, with whom Luce had so recently talked—a Churchill who was still only a lowly M.P. Next in this parade of world-shaking events came the Nazi invasion of Poland on September 1. Europe was at war, and perversely had consummated it too late to get it into the September 4 Time.

Hitler's accommodation with Stahn at long last destroyed Luce's sympathy for him. "Luce went through the special issue war dummy [of Life] with disastrous results," BiUings wrote. "He felt we didn't blame Hitler enough for starting the war, that we were too hard on Britain. ... I called in Kay [Hubert Kay, an editor] and told him . . . Said he: 'When is Harry going to declare war on Germany?' "

2. THE REX LETTER

"I've met the man who ought to be the next President of the United States," Russell Davenport told his wife after his first encounter with Wendell Willkie. Davenport, now managing editor of Fortune, was bowled over by the charming, rumpled Hoosier who headed Commonwealth & Southern Corporation. When WiUkie spent a weekend at the Davenport summer place in Westport, where the Hon cub Davenport had given his wife was tethered to a tree, the Luces were interested guests.

The Roosevelt years which had seen Luce attain wealth and power had seen him largely frustrated in touching the Washington springs of power because he was a Repubhcan, an outsider. He was also sensitive about a hberal establishment, with the President at its head and front, which did not take him seriously as an intellectual. He was well along with his collection of honorary degrees and yearned for membership in the Yale Corporation. His protesting, "I fancy I could be a pretty hot intellectual myself" came from the heart. He was said to have told Clare that he could think of no one mentally his superior—a claim that took her aback and made her mention first Einstein

Luce and His Empire

and then John Kieran. Luce rejected them both, saying Einstein was a spe-ciahst and Kieran "a freak." It seems hkely that Luce ached to be king-maker for a Repubhcan administration that would bring him into the center of power rather than the periphery. He had cheered Willkie's losing fight against TVA. Time had just used one of its subtler pejoratives on Roosevelt's TVA boss David Lilienthal who, it said, had come "out of the White House with his lips twisted in a grin of satisfaction" over the TVA victory. Since Horatio Alger, twisted lips had meant sure villainy and a "grin of satisfaction" suggested the triumph of turpitude.

While Luce investigated President-making, his wife was setting a course for a seat in Congress. She sailed for Italy in February with her friend Margaret Case, a Vogue editor. Miss Case's ultimate mission was to study Paris fashions, Mrs. Luce's to study the quiet confrontation of French and German armies at the Maginot Line which had continued virtually bullet-free for six months and was called in America the Phony War. She planned a book about it which should help her political ambitions. Before going on to France she attended an audience with Pope Pius XII and chatted with Count Galeazzo Ciano, Mussolini's son-in-law and foreign minister, at a Roman dinner party. Quite on her own—she was smashingly independent—she had adopted her husband's moral and political loathing for Communism, though she was not pious.

In Paris she resembled her husband in seeming less critical of Laval's property-conscious rightism than of the Popular Front, the "French New Deal" with its inclusion of Communists. Her mind was keen and tough. What was the French strategy? What did they expect to gain by the Phony War? Did they still hope the Germans might turn on the Russians? Did they believe that Germany would ultimately collapse economically because of the blockade? But what if Germany itself became Communist, a true ally of Russia? She was dubious of the Maginot mind and the French tablecloth generals.

Time had recently opened a small Paris bureau to watch the war. With the aid of its staff and her own acquaintance with Ambassador Bullitt and others, she arranged interviews with public figures and even wangled a visit to the Maginot Line near Metz, where the bored poilus were so impressed by her beauty that they brought her roses. She had been accredited as a Life correspondent. She could be as blunt as her husband in asking questions of strangers. She caught a tartar in Mme. Charles Pomaret, wife of the Minister of Labor, when she said: "Madame Pomaret, we Americans who are friends of France feel that American public opinion, which is largely isolationist, is partly so because we don't quite know what France's war aims are."

Her hostess whirled on her fiercely, put down her champagne and spoke of Uncle Shylock in the last war and of Americans who meddled in French aflFairs. Minister Pomaret, hearing the denunciation, came in. His wife said, "This is Mile. Boothe. She has been asking me the usual stupid question:

W. A. Swanberg

What are France's war aims? America wants to know them!" Pomaret nodded and said, "I am sorry, Miss Boothe, you must go." He opened the door and ushered her out of the ministry.

Undismayed, she cabled Luce urging him to come, adding in the hngo of the dramatist, "The curtain is about to go up on the greatest show the world has ever seen." Luce sailed on the Rex April 13, a few days after the Nazi occupation of Denmark and attack on Norway.

It was as if the Rex was Luce's Mount Sinai, though of course it was only that he now had time to record revelations long growing on him. The cable he had received, the drama of a Europe licked by flames, the action-lover's consciousness that he would soon be there watching the fire, all seem to have inspired the romantic and the prophet in him. He set down his thoughts in an apocalyptic letter to Roy Larsen. He wanted to impart his message, as he put it, "before becoming environmentally involved in Armageddon or whatever it is." The Rex letter, as kingly in tone as the vessel's name, contained a distillation of his beliefs as they bore on America and the world of April 1940. First he philosophized about his power, the power of propaganda:

. . . [Ojur great job [at Time Inc.] from now on is not to create power but to use it. . . . The thought has been inextricably bound up in all our work for a decade. Furthermore the use of power and the creation of it are not separate things—they are inevitably bound up together. But I think you and I share a kind of reluctance to use power—one of the deepest first instincts in the American tradition is perhaps the distrust of power. It would perhaps rather create power, take satisfaction in the creation-—and let its use be free, "democratic," uncontrolled.

To see Time Inc. in perspective is to realize its tremendous potential power. ... I don't particularly like it . . . but there it is.

Perhaps he did not intend this last to be taken literally. He next took up the business of using that power, with a President to be elected, a world war to be settled, and a vital American need, as he saw it, to spread itself ideologically:

. . . [T]here is another [reflection] of more immediate application to the shape of things present & to come. The wild waves and the gentle waves have been telling me that the domestic problem of the United States and the foreign problem of the United States are today one and the same thing. . . . The problem of preserving, expanding, and developing a way of life which is characterized by ideals of freedom, of the integrity and moral responsibility of individuals . . . [A]ll the wisdom to which you & I respond tells us that this great aim cannot be achieved by a U.S. self-contained either economically or ideologically. America has no chance ... of developing the good life as we see it unless there is at least a roughly corresponding development (instead of denial and disintegration) in some of the rest of the world. And this does not mean to me . . . that we must go dashing ofi^ declaring war on Hitler or Hirohito or anybody else tomorrow or the next day. But it does mean that the stakes of American civilization {not prosperity only) are world-wide stakes. . . . The American people do not know this.

Luce and His Empire

You and I know it. . . . So it is up to you and me to do our part to tell the American people that this is really so. . . .

. . . To no one else could I say with the same assurance of understanding: by God, what a job we've done! Only you & I know all the unspectacular headaches—& mistakes! . . .

Selah! God knows what may happen before we meet. . . .

Luce met Clare in Paris, spent a week there talking with French leaders, then went over to barrage-ballooned London, where they stayed as always at Claridge's, a place that satisfied their mutual demand for the best and most prestigious and was only a block from the embassy ruled by the isolationist Joseph Kennedy. Kennedy said the British were as good as licked. "I told him I could not match him argument-for-argument," Luce later recalled. "I could only tell him I did not believe they would be, and so I prayed." It seemed that these two power-seeking men were willing to give each other a push. Kennedy had recently been flattered in a second Time cover story ("grinning, cussing Joe Kennedy, known and loved by millions of English-speaking men"). The ambassador had coaxed Luce to write the preface to Why England Slept, by his twenty-three-year-old son John—an expansion of the young man's Harvard senior thesis on England's failure to prepare for war, to be published later in the year. Luce was impressed by Kennedy's charming second son. He might have been unwilling to write the preface had he known that the ambassador had first approached Harold Laski, Laski having declined on the ground that he felt it "the book of an immature mind; that if it hadn't been written by the son of a very rich man, he wouldn't have found a publisher."

As for Clare, she was exasperated that in the face of all the British disaster the nation could still stomach the same prime minister, writing, "It was a shocking thing to me that long after Mr. Hitler had blown Mr. Chamberlain's Pax Umbrellica inside out, they still let him hold the twisted framework over their heads for protection." The Luces talked with generals, press lords and peers. They spent a weekend at Lady Astor's magnificent Cliveden, where appeasement was no longer in vogue. They made arrangements for audiences with Queen Wilhelmina and King Leopold and flew to Holland May 7.

In contrast to the blaze of spring tulip fields, there were sudden dark rumors that the Germans were coming. The Luces attended dinners with Dutch leaders arranged by American Minister George Gordon, but because of the uneasiness the queen did not see them. On May 9 they went on to Brussels and stayed in the top-floor suite of the American embassy presided over by the rich lawyer John Cudahy.

Luce soon had that peculiar good fortune so often yearned for by newspapermen—physical presence at the scene of great and dangerous events— though in his case it was perhaps less luck than his insistence on such constant search for events that he could scarcely avoid occasional collisions with them. At 5:25 next morning a maid rushed in shrieking "Les Allemands!" Hearing

W. A. Swanberg

planes, the Luces leaped from their beds. "We were at the window looking down into the street when we heard a tremendous explosion," Luce said later. "The house across the street collapsed. The sirens began to blow."

Their appointment with King Leopold was at ten, but the king had other duties that morning. The two Luces were alike in a disregard for danger which they would demonstrate repeatedly. Some forty people had already been killed in the air raids. Ambassador Cudahy urged them to leave immediately, but they insisted on staying for an embassy dinner that evening. By then the bombs were fewer and quite distant, evidently hitting the airport. Luce had cabled the home office in part:

Your special correspondent, Clare Boothe, is sending Billings a brief eyewitness account of the first day of the German's grand attack on the Western world. I hope Life can use it this week as a signed item in a lead story. ... [It was given subsidiary position.] If you were here today, remembering 1914, you would be sad but also you would be plenty, plenty mad. The word Boche is the only word used on the streets today to describe the enemy, and no other word would sound right. I deeply wish all priggish, pious pacifists could be here today.

In the morning they hired a car and headed for Paris, passing refugees in carts, bicycles and haywagons—then British troops singing as they marched northward to meet the Germans. They passed a symbol now ironic, the monument to the dead at Vimy Ridge. In Paris they found many bejeweled residents of the Ritz terrified. Perhaps their terror was no worse than that which would be shown by any nationals in such a situation, but Luce felt the special contempt he held for a nation whose government, like the Literary Digest, had failed to measure up to its competition. The behever in heroes looked vainly for them in crumbling France—for men who had the courage, conviction and style to rally a demorahzed people. The behever in aristocracy perhaps blamed it on the erosions of the Popular Front, though England's Tories had done httle better. But now at the last moment England had produced a hero, Churchill having just become prime minister. Luce, scanning the horizon for heroes, took some comfort in a statement of sympathy for the invaded countries by the Pope, and shock and anger expressed by President Roosevelt. A cable he sent home made clear his impatience with anyone thinking America had nothing to do with this war:

The remarks of Roosevelt and the Pope sound wonderful here. I am practically prepared to become both a Catholic and a Third Termer unless the opposition offers some small degree of competition. Unless the others move awful fast, it looks like Davenport's man [WiUkie] is the only Republican who can get this [Luce's] homecoming vote.

Sober and long experienced observers say it is utterly irrelevant to discuss right and wrong in connection with the present German regime. The simple fact is that the Germans will stop at nothing to get what they want and there is utterly no evidence that they want anything less than all they can get by the most

Luce and His Empire

ruthless means. Whether or not they bomb civihans is similarly irrelevant, because they will not waste ammunition if it serves no purpose, and they will not hesitate to destroy every woman and child in Belgium if they can gain thereby . . . [T]he United States is indulging in complete and criminal folly unless it proceeds at once to build every single military airplane it can possibly make in the next six months. Never mind who uses them, never mind who pays, but for God's sake, make them. Similarly, all possible military equipment of every sort should be ordered at once, regardless of cost.

If Life and Time fail to sell this idea now, it probably won't matter much what these estimable publications say in years to come. . . . The Germans have one weapon greater than all their army and that is the blindness and stultification of those in every country who are too fat to fight.

1. THE WILLKIE-LUCE LEAGUE

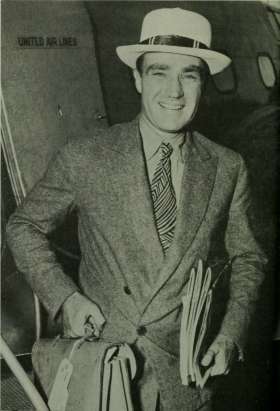

Luce came home, the columnist Jay Frankhn said, "hke a bat out of Flanders with a demand for national unity." He reached New York alone May 20, his venturesome wife remaining behind to stay with the Kennedys and see more of Europe's convulsions. Luce's heady patriotism and politics revolved around his conception of what he called the American Proposition (Clare shortened it to Amprop), in which he saw the nation as destined to spread freedom and prosperity around the world. He came shouting, like Paul Revere, that America must wake up. The born competitor knew that America must compete— quickly—with Hitler. Two days after his return he made his first nationwide broadcast over NBC: ". . . i/Great Britain and France fail, we know that we and we only among the great powers are left to defend the democratic faith throughout the world. . . . We have to prepare ourselves to meet force with force—to meet force with superior force." He sounded the warning over the Columbia network: "If we deal with the Third Reich on a basis of appeasement of any kind, it will follow as sure as night follows day that we will pay for it ... in the bloody end of all our democracy. We must deal with Hitler as with an enemy. . . ."

As he would in later crises, he seemed impatient for America to go in and solve it, angering isolationists. Senator Burton K. Wheeler referred to his speeches as "really advocating that we get into the war."

He was implementing the Rex letter, telling the American people what he knew and they did not. He gave up on Thomas E. Dewey and Senator Taft as Republican candidates because they dodged the war issue, and came out for Willkie, the anti-isolationist, the viewer of America as part of the world. Life frankly beat the drum for Willkie, Fortune published Willkie's article "We

176

Luce and His Empire

The People," as Joseph Barnes noted, "accompanied by what was practically a nomination of him by the Luce editorial board," and Davenport resigned to become Willkie's right-hand man. Still, when Luce went to the Republican convention in Philadelphia in June, Willkie was a very dark horse. His nomination on the sixth ballot was a surprise which the Lucepress cheered, and Luce won the suspicion of the isolationist Republican Old Guard who disliked the Johnny-come-lately Willkie's internationalism and former Democratic allegiance.

Thereafter Luce became a trusted Willkie adviser. No one—not even his father—dared walk into Luce's penthouse office unannounced, but Willkie did so repeatedly without injury. "He looked like a big bear," Miss Thrasher recalled. "He'd come in about 6:30, say good evening to me and walk right in to Mr. Luce's office. Mr. Willkie would put his feet up on one side of the desk and Mr. Luce would put his feet up on the other and tell me, 'You can go home now.' I have no idea how long they talked."

When John Kennedy's book Why England Slept was published August 1, Luce's foreword stressed one of the reasons Kennedy gave for Britain's failure to prepare: "A boxer cannot work himself into proper psychological and physical condition for a fight that he seriously believes will never come off." Now, said Luce, America had the same trouble. We had to believe war was coming, but so far neither of the candidates seemed to believe it, not even Luce's candidate:

[Mr. Roosevelt] can't believe we are ever going to fight. Otherwise how can he so glibly guarantee that we will not need to sacrifice one tiniest bit of our "social gains." . . . Mr. Willkie may reasonably be pardoned [on political grounds] for presenting himself to the Republican Convention as a prime keep-out-of-war man. . . . But all his genius of personality and industrial management will be bitter ashes in our mouths if Mr. Willkie goes forth to prepare for a war which he leads us to believe isn't really ever going to happen.

Young Kennedy came in to chat with Luce, brightening the office with his Irish smile, charming Miss Thrasher by giving her an autographed copy of the book, being granted a few minutes of Luce's time because he was Joe Kennedy's son.

"Mr. Luce was very anxious for Mr. Willkie to be elected," Miss Thrasher recalled in great understatement. Luce longed to become Secretary of State, a position for which he felt himself to have special qualifications which it is un-hkely that he concealed from Willkie. While his journalist-propagandist status was as questionable as ever, his call for national dedication was one the administration itself would adopt, and none too soon. Confidentially Luce warned his senior men that it was their "journalistic duty" to sound the danger signal, to "cultivate the Martial Spirit" and to be "savage and ferocious in our criticism of all delay and bungling." He visited Secretary of State Hull to argue for the transfer of over-age destroyers to the hard-pressed British, and

W. A. Swanberg

later urged this on the President himself. Luce's hearing was deteriorating—a handicap he perhaps mentioned obliquely in his rather grandiose memorandum:

After dinner Prex and I have a private talk in the Oval Room. My big question is, has he or has he not made up his mind about sending destroyers to Great Britain. I understand him to say definitely that "it's out" . . .

Not long thereafter, the destroyer deal was made. Meanwhile, National Affairs Editor Matthews aroused the Lucean ire. Although Matthews opposed a third term and was nominally for Willkie, he did not share Luce's propagandist audacity. The inexperienced and impulsive Republican candidate made errors that Time reported just as if he had been a Democrat. The canny President made few, and Time in some issues reached an approximation of fair political reporting. It was all very well for Time to praise Willkie's personality and courage and to describe him as "the hardest-hitting extemporaneous day-by-day debater of public issues whom the Republicans have had for a candidate since Roosevelt I." But when the same issue said some Republican professionals feared that Willkie was muffing his opportunities and might be "only a fatter, louder Alf Landon," Luce exploded. Felix Belair, Time's new Washington man, had suffered the jeers of other newsmen because of the magazine's pro-Willkieism. He showed his misunderstanding of Luce, who of course had no wish to be objective, when he observed that the story "did more to clinch Time Inc.'s reputation as an objective publishing house than any other recent development. "

Matthews, who was working sixty hours or more a week, recalled: "Luce called me up at home to complain, in a long, rambling, furious diatribe . . . When I got a chance to speak I told him, with equal fury, that if he ever again called me at home on a Wednesday ... I would resign on the spot . . . Wednesday was the one day I had with my family, it was a sacred day, and was never to be trespassed on again. He apologized handsomely . . ."

Luce thereafter reserved his complaining for the other six days, but Matthews stood him off as no other editor ever did. Time later reported Willkie's splitting of an infinitive, told of crowds booing him in Michigan and elsewhere, and said he seemed to promise rather a lot when he said, "I pledge a new world."

Now and then Luce would get a Willkie speech idea in the small hours and would telephone it to Miss Thrasher at her West 73rd Street home through the Time switchboard. She would take the Elevated through the night to the T-L Building, where she would give the information to the Willkie campaign train on Luce's private wire. She might get home at four, but she would be at work at 8:30, not minding it at all because "it was all so exciting." Clare, returned from Europe, took the stump in reply when Dorothy Thompson switched her support in October from Willkie to Roosevelt. The two women at times forgot their candidates in the heat of their own contest. Because Miss

1. Vestigial wings seem visible on the baby Henry Luce, first-born of missionaries in China. Below, at three, the forceful tycoon is in the ascendant.

■J"*#i

2. Mother Luce with young Harry, Enimavail, EHsabeth (seated) and baby Sheldon.

3. Rev. Henry Winters Luce (seen in later life) was red-headed, dedicated, sometimes tactless enough to discompose his seniors.

4. Level, challenging gaze marks young Luce (standing, extreme left) with classmates at Chefoo School, where he upheld America in a preponderantl)- British atmosphere.

5. The collegian shavetail Luce (left) appears below in his guise as managing editor of the Yale Daily Ne\\s. He is to left of Chairman Briton Hadden, seated in center, with staff. Hadden, the biggest man on campus, would retain that status as Luce's partner in magazine enterprise.

6. The beautiful and charming Lihi Luce, who tried to slow down her driving husband, wrote him, "I am going to kidnap you and take you to some leafy solitude ... to laugh." Not laughter but t\pical Luce intensity is conspicuous at right.

7. Divorce was in the ofRng when Daniel Longwell carried a romantic Luce message to Clare Brokaw (shown with daughter Ann) in Salzburg, far from New York gossip.

8. The jovial but Napoleonic Hadden rather upstaged his partner Luce from the beginning. Their growing estrangement was solved tragically by Hadden's death.

9. Archibald MacLeish was first to protest Time's manipulation of news. Laird S. Goldsborough (below, right) was storm center of the staff ideological warfare.

fVStMr

■V>

^'-i^ ^.-'^u-' .;>.1

■1-? ■?

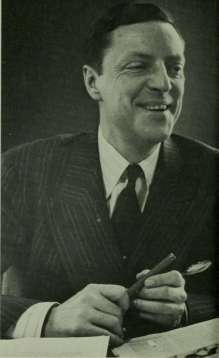

10. The talented John Shaw BilHngs became Luce's editorial chieftain, responsible for Time, Life and Fortune. 9H^t

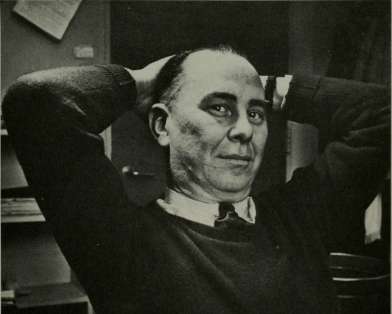

IL Ralph IngersoU (below). His opposition to Luce ended his Time Inc. career. T. S. Matthe\\s (below, right) also fought Luce and was later ingeniously jettisoned.

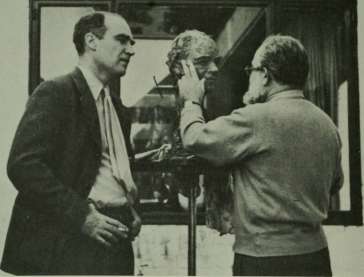

12. At Mepkin, Jo Daxidson fashions bust of Luce. Below, the propulsive tycoon exhibits most dazzling smile ever photographed of his usually serious countenance.

13. In the famous courtroom confrontation Whittaker Chambers stands (left) to identify Alger Hiss (standing, right). Below: Close-up of reformed Communist Chambers.

14. John Herse}' (left), a Luce favorite, fell out with him over news slanting. Allen Grover (right) found a European tour with the Boss an exhausting e.xperience.

13. Luce in China with Theodore White, another fa\ orite soon to be thrown overboard.

16. The liberal Eric Hodgins (left) deplored the ascendancy of Goldy and then Chambers. C. D. Jackson (right) ate crow for Life before Hollywood right-wingers.

17. Roy Alexander (below) survived as the Boss's companion on three long tours.

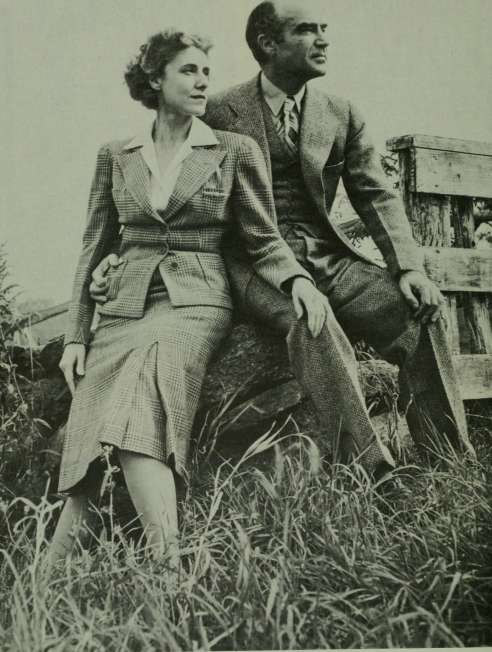

18. The "miracle editor" and his Congresswoman second wife in pastoral Connecticut.

19. In his heyday—striking if not handsome, attractive to women, flinty of eye.

20. Wendell Willkie would probably have named Luce his Secretary of State. Below: Chiang Kai-shek and Madame were promoted to stardom in the laudatory Lucepress.

I

JUU-

H^MHY vv\rc %'^^ \rtt liuhN^L^^^

21. Tsingtao journalists fawn over the revered visitor (center) in 1945. Below: With H. H. Kung he dedicates propagandist China House he founded in New York.

22. Luce and his ensign son Hank meet by chance in mid-Pacific.

23. Congresswoman Luce acknowledges ovation for "GI Jim" speech.

Luce and His Empire

Thompson had visited the Maginot Line a few weeks after Clare and had been permitted to fire a gun, Clare called her "the Molly Pitcher of the Maginot Line," attributed her switch to "hysteria" and said, "I was the first American woman to be taken on an official conducted tour of the Maginot Line. Dorothy Thompson was the second—and last." Miss Thompson replied:

Miss Boothe is the Body by Fisher in this campaign. She is the Brenda Frazier of the Great Crusade. She has torn herself loose from the Stork Club to serve her country in this serious hour. ... I have met the ladies of cafe society who save nations in their time of crisis, and I have visited the nations they have saved. . . .